Abstract

Aims

To explore racial differences in adiponectin and leptin and their relationship with islet autoimmunity in children with new onset T1D.

Methods

Medical records were reviewed from a cohort of new onset clinically diagnosed T1D subjects matched by race, age, gender, and year of diagnosis. Sera were available for 156 subjects (77 African American (AA), 79 Caucasian (C), 48% male, age 11.1± 3.8 years) and assayed for adiponectin and leptin prior to (D0), 3, 5 days, and 2-4 months (M3) after insulin therapy and islet autoantibodies to GAD, IA2, insulin, and ICA were measured at onset.

Results

Adiponectin levels increased significantly following insulin therapy by day 5 (D5) (D0: 13.7 ± 7.2 vs. D5: 21.3 ± 9.9 μg/mL, p<0.0001), but no further significant increase from D5 to M3. At DO, AA had lower adiponectin levels (10.5 vs. 15.7 μg/mL, p=0.01), were more often overweight than C (55% vs. 18%, BMI ≥ 85th %ile) and fewer had positive autoantibodies (72% vs. 87%, p=0.05). Racial differences in adipocytokines disappeared after adjustment for BMI. At M3, subjects with greater numbers of positive autoantibodies had higher adiponectin levels (p=0.043) and adiponectin: leptin ratio (ALR) (p=0.01), and lower leptin levels (p=0.016).

Conclusion

Adiponectin levels increased acutely with insulin therapy. Significantly lower adiponectin levels in AA were related to greater adiposity and not race. These pilot data showing those with the fewest autoantibodies had the lowest adiponectin levels, support the concept that insulin resistant subjects may present with clinical T1D at earlier stages of β-cell damage.

Keywords: Adiponectin, Leptin, Adipokines, diabetes mellitus, type 1, child

Introduction

The prevalence of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in the pediatric population has increased in the past decade in all ethnic groups (1). Although in the past, these patients were almost exclusively lean or underweight, in recent years there has been a shift toward a younger age and increasing frequency of obesity (2, 3). Our previous studies showed an inverse relationship between body mass index (BMI) and the number of positive islet-cell autoantibodies which led us to hypothesize that obesity associated insulin resistance (IR) results in accelerated clinical presentation of T1D at an early stage of β-cell destruction (4). This is in contrast to Wilkin's “accelerator hypothesis” which theorizes that obesity-associated IR is an initiator of autoimmunity (5). Adipocytokines, hormones secreted exclusively by adipose tissue, may provide further insight into the role of obesity and IR in β-cell antigen spreading in children with new onset diabetes.

Adiponectin may be of particular relevance due to its association with insulin sensitivity, but it is also affected by insulin deficiency. In vitro and rodent studies have demonstrated the role of ambient insulin in the production and secretion of adiponectin, but this has not yet been reported in vivo in humans (6, 7). Adiponectin levels are low in human obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes (8). Paradoxically, high adiponectin levels, specifically the high molecular weight isoform, have been reported in established TID (9-11). Despite this, adiponectin levels have been reported to be positively correlated with insulin sensitivity in adults with TID, although these patients had overall lower insulin sensitivity than healthy controls, suggesting dysregulation of adiponectin function in T1D (11). Leptin, the adipocytokine product of the Ob(Lep) gene, reflects the degree of adiposity (12, 13) and is stimulated by insulin, rising acutely with insulin therapy in both in vitro rodent studies and in children with new onset T1D (14-16). The adiponectin:leptin ratio (ALR) has been used in studies of type 1 and type 2 diabetes as a surrogate measure of insulin sensitivity (17).

Racial differences in adiponectin and leptin levels have been described in the literature. Lower adiponectin levels are seen in non-diabetic African American (AA) youth, potentially predisposing them to greater risk of insulin resistance despite lower visceral fat (18). A recent study showed that AA children ≥10 years of age with newly diagnosed T1D had higher levels of leptin compared to their Hispanic and Caucasian counterparts (19). This finding is consistent with previous studies done in healthy adults (20-22) and children (23).

This pilot investigation aims to evaluate whether, like leptin, adiponectin levels are low in the insulin deficient state and increase with insulin therapy. We also assessed racial differences and evaluated the concept that adiposity/IR, as assessed by adipocytokine levels, is related to islet autoantibody number as a marker of islet cell damage.

Methods

Subjects

For this pilot study, 156 subjects with available stored serum were included (77 Caucasian and 79 AA). These represent 60% of a previously studied cohort of 260 new onset T1D subjects consisting of all 130 AA children diagnosed between 1 January 1979 and 31 December 1998 at the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC (CHP) who were matched by sex, age (within 1 year), and year of diagnosis (within 1 year) to an equal number of Caucasians who were part of the CHP Diabetes Registry (2). Criteria for inclusion were: (i) admitted to CHP with new-onset diabetes determined to be insulin requiring by a physician; (ii) less than 19 yrs. of age at diagnosis; (iii) treated with insulin therapy at hospital discharge; and (iv) sufficient sera for measurement of adiponectin and leptin. All cases of secondary diabetes, MODY, non-insulin requiring type 2 diabetes, diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria, were excluded. The general treatment philosophy was to start insulin therapy in all patients with clinically apparent T1D, based on the presence of ketosis and/or severe hyperglycemia and/or marked weight loss, irrespective of the presence of obesity. Blood samples were obtained prior to insulin therapy, 1, 3, and 5 days following insulin therapy and at the first follow-up visit. All blood samples were stored at -80 C after initial testing for islet autoantibodies. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects (4).

Clinical and Biochemical Data

Demographic and clinical data including age at diagnosis, gender, race, height, weight, BMI, presence of serum and/or urinary ketones, and blood pressure, were obtained from review of the medical records. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 85th % for age and for gender.

Autoantibody assays

Blood samples obtained within 1 week of diagnosis were assayed for insulin autoantibodies (IAA) and /or within 3 months for islet cell antibodies (ICA), and antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GADAA) and IA-2AA (ICA 512). β-cell antibody positivity was defined as the presence of at least one of the four autoantibodies. All antibodies were measured in our research laboratories as part of the research protocol. Assay methodology, sensitivity and specificity were previously published by our group in the same patient population. In addition to assays using human pancreas, ICA was measured by a using cafeteria-fed rat fresh frozen pancreas (2, 4).

Adiponectin and Leptin assays

Serum total adiponectin levels were determined by radioimmunoassay (Human adiponectin RIA kit, Linco Research, St Charles, Missouri, USA). The assay range of detection is 1 - 200 μg/mL. All serum sample duplicates with more than 10% coefficient of variation (CV) were repeated. The intra-assay CV was 4.2-8.3 %, and the inter-assay CV was 15.6 – 20.5% for the high and low end respectively.

Serum leptin levels were determined by ELISA (Human Leptin ELISA kit, Linco Research, St. Charles, Missouri, USA). The assay range of detection is 0.5-100 ng/mL. Duplicates that differed by more than a 10 % CV were repeated. The intra-assay CV was 1.6-12%, and the inter-assay CV was 5.9-24% for the high and low end respectively.

Statistical analyses

All data were examined for distributional characteristics and descriptive summaries were reviewed. Proportions were used to summarize categorical variables. Comparisons of continuous variables were assessed using t-test and ANOVA procedures, depending on the number of groups. Comparisons of proportions for categorical variables between subgroups were done using chi-square test procedures. Correlations between different variables were assessed using Pearson correlation coefficients. If distributional assumptions of the testing procedures were not met, nonparametric procedures such as Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal Wallis (KW), and Spearman rank procedures were employed. The Jonckheere-Terpstra (JT) test was used to evaluate ordered differences in adiponectin, leptin, and ALR among subgroups of autoantibody number. Multivariate logistic regression was used to adjust for the effect of confounding variables such as BMI. Linear mixed models were used to compare cytokine levels longitudinally while adjusting for multiple covariates. Bonferroni adjustment was used for multiple comparisons.

Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 and Cytel StatXact 10 Procs for SAS. As this was a pilot study, all statistical hypothesis testing was conducted as 2-sided tests and significance was considered p<0.05

Results

Subject Demographics

The study demographics are summarized in Table 1. There were no statistically significant racial differences at diagnosis in mean HbA1c or presence of ketonuria. However, AA subjects were significantly more overweight and had fewer positive autoantibodies. By month 3, the BMI increased significantly in both Caucasians (p<0.001) and AA (p<0.001) and AA subjects remained significantly more overweight than Caucasians (57.8% vs. 21%, p<0.001). The proportion of autoantibody negative subjects was higher in those with BMI ≥85% in both Caucasians (21%) and AA (47.7%). However, of those subjects who were negative for conventional autoantibodies, 27% (6 AA, 3 Caucasian) demonstrated ICA using cafeteria-fed rat pancreas, suggesting the presence of other autoantibodies. Acanthosis was common in obese subjects irrespective of their autoantibody status (4).

Table 1. Study Demographics.

| Variable | Caucasian | African American | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 77 | 79 | |

| Male/Female (%) | 45/55 | 49/51 | NS |

| Age at dx, yrs.* | 11.1 ± 3.9 (1.4-18.1) | 11.1 ± 3.8 (2-18.1) | NS |

| BMI, kg/m2; (onset)** | 16.7 [14.8-20.4] | 21.3 [15.1-29.9] | <0.001 |

| BMI percentile (onset)** | 35.9 [7.3-75.6] | 89.8 [23.8-97.6] | <0.001 |

| Obesity (%), onset (n)† | 18 (14) | 55 (44) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2; (3 months)** | 18.7 [16.5-21.8] | 23.4 [18.1-31.7] | <0.001 |

| BMI percentile (3 months)** | 62.1 [44.2-78.1] | 94.5 [72.9-98.2] | <0.001 |

| Obesity (%), 3 months (n) † | 21 (12) | 57.8 (37) | <0.001 |

| Autoantibody negative (%) (n)‡ | 13 (10) | 28 (22) | 0.005 |

Values represent means ± SD and range

Values represent median [interquartile range]

Obesity defined as BMI≥85th percentile for age and gender.

Subjects identified as antibody negative if they had 4 negative conventional auto-antibodies (ICA, IAA, GADAA and IA-2 AA)

Effect of acute insulin therapy on adipocytokine levels

To assess change in adiponectin levels following insulin therapy paired analysis using Wilcoxon rank sign test was used for subjects with samples at two time points. Given that subjects within the first 24 hours of insulin therapy remain insulin deficient and likely glucotoxic, these values were combined and labeled as D0. Analysis of 15 paired samples from D0 and day3 (D3) did not show a significant increase in adiponectin (11.9 [6.7-17.5] vs. 16.1 [9.9-22.5 μg/mL], median [IQR], p=0.2]. There was a significant increase in adiponectin from D0 to day 5 (D5): (16.6 [10.4-22.1] vs. 20.5 [14-23.9 μg/mL], p=0.004, n= 27] and D0 to month 3 (M3): [10.7 [7.6-14] vs. 18.5 [12.8-20.2 μg/mL], p=0.04, n= 13].

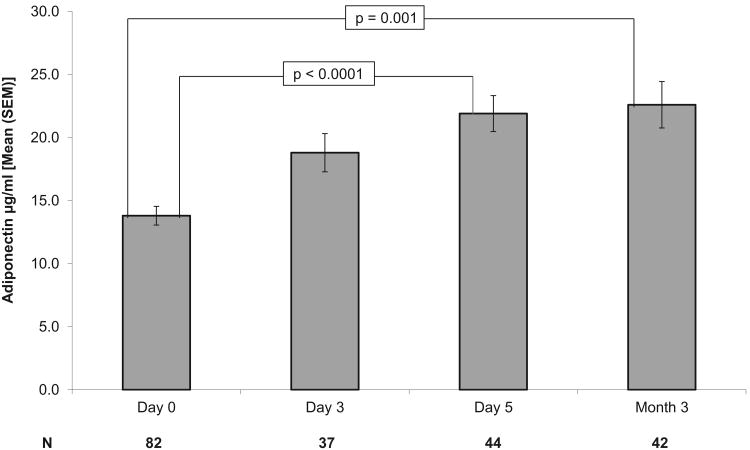

We then examined all available data cross-sectionally using a linear mixed modeling approach. We demonstrated that the mean levels of adiponectin increased significantly (F=15.5, p<0.0001) across the four time periods (D0, D3, D5, and M3). Least square modeled estimates of adiponectin are 14.4, 17.7, 19.8, and 22.1 μg/mL at D0, D3, D5, and M3, respectively. Cross-sectional comparison of mean adiponectin levels at each time point (Bonferroni adjusted) indicated significant differences between D0 and D5 (13.7 ± 7.2 vs. 21.3 ± 9.9 μg/mL, mean ± SD, p<0.0001), and D0 and M3 (13.7 ± 7.2 vs. 21 ± 11.1 μg/mL, p<0.0001). There was no significant increase in adiponectin from D5 to M3 (21.3 ± 9.9 vs. 21 ± 11.1 μg/mL, p=1) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Longitudinal Adiponectin Levels

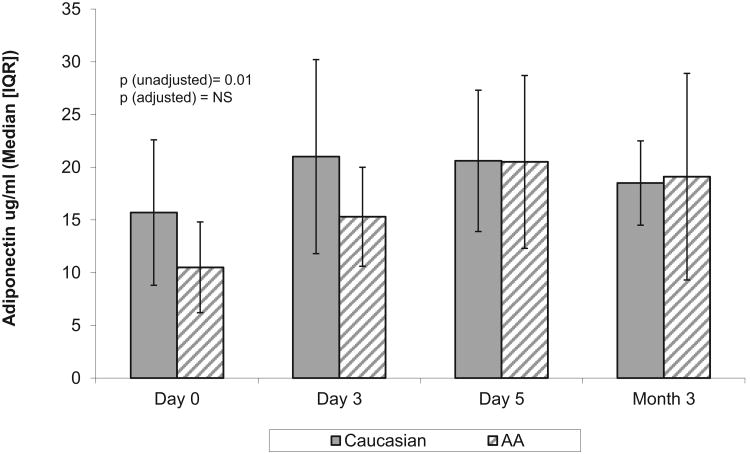

Racial differences adipocytokine values

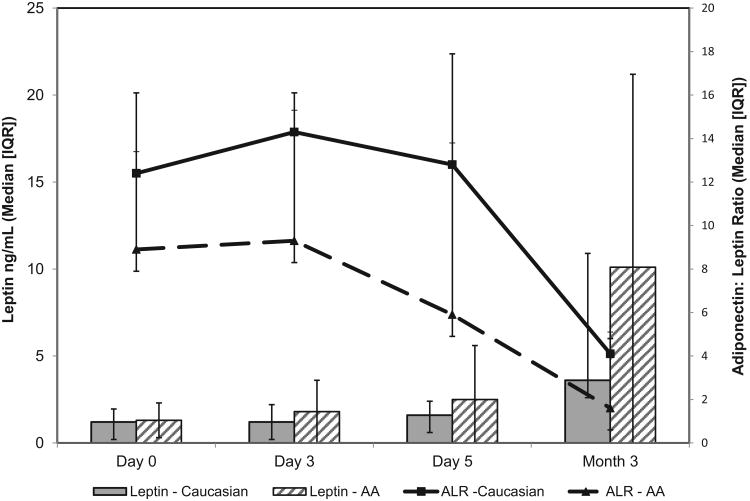

At diagnosis, AA were more often overweight than whites (55% vs. 18% with BMI > 85th %ile) and fewer had positive autoantibodies (72% vs. 87%, p=0.05). As seen in Table 2 the only significant racial differences in adipokine levels were at D0 for adiponectin and this difference did not persist after adjusting for BMI. By M3, adiponectin levels in AA increased more than in Caucasians, but this did not reach significance with levels similar in AA and Caucasians [Figure 2]. A negative correlation between adiponectin levels and BMI%ile at D0 only reached statistical significance in Caucasians (AA: r=-0.22, p=0.1 vs. Caucasians: r=-0.45, p-<0.001). In contrast, leptin levels were not significantly different between races at D0 (1.3 [0.5-2.5] vs. 1.2 [0.7-2.2 ng/mL], p=0.6) and levels increased significantly from D0 to M3 in both AA and Caucasians. AA had a trend toward higher leptin at M3 but this did not reach statistical significance [Table 2]. In AA, leptin correlated with BMI %ile at D0 (r=0.33, p=0.007), with a similar trend in Caucasians (r=0.24, p=0.06). ALR was not significantly different between AA and Caucasians at any time point [Table 2 and Figure 3] and negatively correlated with BMI%ile in both groups on D0 (AA: r= -0.38, p=0.002, C: r=-0.4, p=0.001). Age was related to ALR at D0 and M3 only in AA (r= -0.28, p<0.03 and r= -0.56, p=0.003) and this negative correlation persisted after adjusting for BMI at M3 (r= -0.47, p=0.02). In contrast, there were no significant relationships between age and ALR in Caucasians.

Table 2. Racial differences in longitudinal adipocytokine values.

| Variable | Caucasian | African American | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin D0 (μg/ml) | 15.7 [9.2-22.9]† n = 44 |

10.5 [7.1-15.8] n = 38 |

0.01 |

| Adiponectin D3 | 21.0 [10.1-28.5] n = 19 |

15.3 [9.35-18.8] n = 18 |

0.17 |

| Adiponectin D5 | 20.6 [15-28.3] n = 25 |

20.5 [13.7-30.2] n = 19 |

0.7 |

| Adiponectin M3 | 18.5 [15-23] n = 17 |

19.1 [11.2-30.8] n = 25 |

0.8 |

| Leptin D0 (ng/mL) | 1.2[0.7-2.2] n = 42 |

1.3 [0.5-2.5] n = 37 |

0.9 |

| Leptin D3 | 1.2 [0.5-2.5] n = 18 |

1.8 [0.8-4.4] n = 18 |

0.3 |

| Leptin D5 | 1.6 [0.8-2.6] n = 25 |

2.5 [0.9-7.2] n = 20 |

0.2 |

| Leptin M3 | 3.6 [1.6-16.2] n = 18 |

10.1 [2.1-24.3] n = 26 |

0.08 |

| Adiponectin/Leptin Ratio D0 | 12.4 [5-23.8] n = 42 |

8.9 [3.9-18.3] n = 37 |

0.2 |

| Adiponectin/Leptin Ratio D3 | 14.3 [6.7-27.2] n = 18 |

9.3 [2.2-15.7] n = 18 |

0.16 |

| Adiponectin/Leptin Ratio D5 | 12.8 [6.3-27.5] n = 25 |

5.9 [3-27.5] n = 19 |

0.3 |

| Adiponectin/Leptin Ratio M3 | 4.1 [1.5-9.7] n = 16 |

1.6 [0.8-7.2] n = 25 |

0.25 |

Values represent median [interquartile range]

Figure 2. Longitudinal Adiponectin Levels by Race.

Figure 3. Longitudinal Leptin and ALR by Race.

Relationship between adipocytokine levels, BMI, and islet autoantibodies

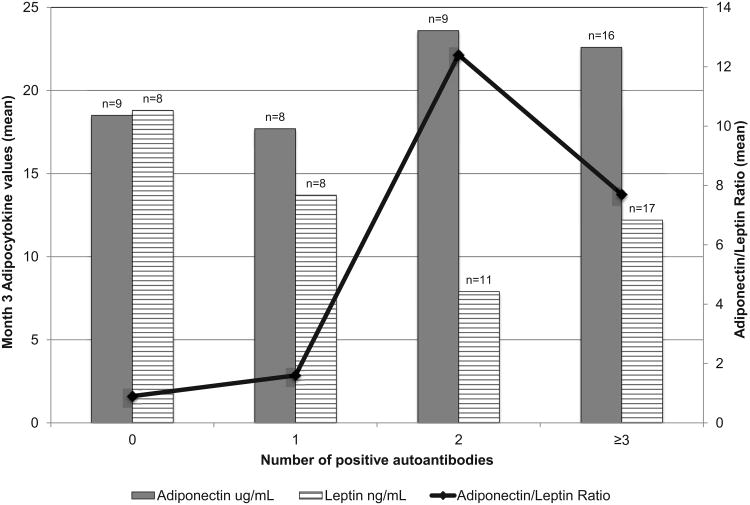

In the remission period at M3, after the effects of insulin deficiency and glucotoxicity were reversed, and the adipocytokine levels had stabilized to presumable pre-diabetes levels, their relationship with adiposity and number of positive islet cell antibodies was assessed. Leptin positively correlated with BMI z-score (r=0.48, p=0.0028) and the adiponectin leptin ratio negatively correlated with BMI z-score (r=-0.46, p=0.004). Subjects with greater numbers of positive autoantibodies (0, 1, 2, ≥ 3) had a trend toward higher adiponectin levels (p=0.052, Jonkheere-Terpstra test) and higher ALR (p=0.0512) with no significant difference in leptin levels (p=0.11) [Figure 4]. We then compared the adiponectin, leptin, and ALR of those subjects with 0-1 positive autoantibodies and those with ≥2 autoantibodies using the Wilcoxon Mann Whitney Test. Subjects with ≥2 positive autoantibodies had higher adiponectin levels (p=0.043), lower leptin levels (p=0.016), and higher ALR (p=0.01) than those with 0-1 positive autoantibodies. After adjustment for overweight status at 3 months (BMI <85th%ile vs. ≥ 85th%ile) this finding was no longer significant: adiponectin (p=0.054), leptin (p=0.38), ALR (p=0.18).

Figure 4. Month 3 Adipocytokines by Number of Autoantibodies.

Discussion

As has been seen in in vitro studies and in animal models (24, 25), and previously described with leptin (16), adiponectin levels increase as early as three days after initiation of insulin therapy with a statistically significant increase by day 5. Our data supports an insulin-mediated increase in adiponectin levels, given that the time period is too short to be attributed to a significant change in adiposity or HbA1c. Although the relationship between insulin and adiponectin has been extensively studied, the literature on the exact mechanism of insulin-stimulated adiponectin gene expression, production, and secretion is obscure. In vitro studies performed in 3T3-L1 adipocytes have shown that insulin stimulates adiponectin secretion via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (P13K) signaling pathway (26) and stimulates both the synthesis and secretion of adiponectin (25). To date, studies have not systematically looked at how adiponectin secretion from the adipocyte in response to insulin is altered following exposure to significant hyperglycemia and/or insulinopenia as would occur in our subjects with new onset T1D. We found no significant increase in adiponectin levels from day 5 to month 3 of insulin therapy in our subjects, suggesting stabilization after 5 days of insulin therapy. In patients with new onset T1D, there is a reversal of insulinopenia as well as resolution of glucotoxicity- related insulin resistance after few days of insulin therapy (27). Our data may be associated with both mechanisms.

Using the month 3 adiponectin as a surrogate marker of insulin sensitivity, there was an apparent inverse relationship between IR and autoantibody number. Those subjects with the greatest number of positive autoantibodies had higher adiponectin, lower leptin, and higher adiponectin/leptin ratios than those with lower numbers of positive antibodies. The ALR appeared to separate those with 0 or 1 positive antibodies and 2 or more positive antibodies with those subjects with the lowest ratio having the fewest positive antibodies. This effect became insignificant when adjusted for BMI suggesting that adiposity is the major determinant. The ALR has been reported by the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study to be associated with diabetes type above and beyond adiposity in patients with both type1 and type 2 diabetes of longer diabetes duration. This association was thought to be due to differences in adiponectin but not leptin suggesting that IR is not explained by adiposity alone (17).

Adiponectin levels, specifically the high molecular weight isoform, are increased rather than decreased in a number of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, including T1D (9, 10). A study by Kaas, et al., showed that patients with rapidly progressive T1D, defined as loss of more than 20% of their C-peptide in the first 6 months following diagnosis, displayed increased serum adiponectin compared to slow progresser and remitter groups (28). The patients in this study with 3 positive antibodies were most likely to be in the rapid progresser group with the highest serum adiponectin (28). This is similar to our finding of increasing adiponectin levels with increasing number of positive autoantibodies. Further longitudinal studies of adiponectin and the complexity of its biologic and metabolic function are needed to better elucidate the role of adiponectin in patients with Type 1 diabetes.

Although subjects with negative beta-cell autoantibodies are by convention classified as type 2 diabetes, the clinical presentation of our subjects suggested insulin deficiency. Using the conventional measurement of autoantibodies to islet antigens, 22% of AA and 10% of Caucasian subjects would have been designated as autoantibody negative. However, the presence of other measures of autoimmunity, demonstrated by antibodies to islet antigens expressed by cafeteria-fed rat pancreas showed that 27% of those without conventional antibodies (n=9, 6 of whom were AA and 3 of whom were Caucasian) had autoimmune evidence representing some degree of β-cell destruction, a concept supported by the frequent presence of T cell autoimmunity in autoantibody negative diabetic children (29, 30). Follow-up data is available for 5 of these 9 subjects, all of whom were on a minimum of 0.8 units/kg/day of insulin after 2 years. Our data supports the concept that insulin resistant subjects present with clinical diabetes at a stage of less severe β-cell damage as evidenced by fewer islet cell antibodies. It is not clear from our data whether this is related to increased insulin demand secondary to obesity-related insulin resistance or to obesity-induced cytokine damage.

Racial differences in adiponectin and leptin levels are well described in the literature; however, data on racial differences in children with T1D is limited. We found that adiponectin levels were significantly lower in AA than Caucasian children at D0; however this finding lost significance after adjustment for BMI. After adjustment for BMI, there were also no significant racial differences in leptin or ALR at any time point. Our data suggests that body composition rather than race is a more significant determinant of adipokine levels.

Our study is unique in that it explored racial differences in adiponectin and leptin in an equally matched population of AA and Caucasian children who were followed longitudinally after the diagnosis of T1D. Some limitations of our present study should be pointed out. Given that this pilot study was retrospective, serum was not available for all patients for measurements of adiponectin and leptin leading to smaller numbers on longitudinal follow-up. It will be necessary to evaluate serum adiponectin and leptin and their relationship to islet autoantibodies in a larger prospective study in order to confirm our findings.

In summary, we found that as reported for leptin (16), adiponectin levels increase acutely with insulin therapy and that racial differences were explained by adiposity. Using adiponectin levels as a surrogate for IR, there is an inverse relationship between IR and autoantibody number in subjects with new onset T1D. This supports the concept that there may be acceleration of the clinical presentation of T1D in insulin resistant subjects occurring at earlier stages of beta cell damage.

Acknowledgments

This work was supped in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK-24021020 (D.J.B.) and R01-DK-53456 and R01-DK-56200 (M.P.), a resident research grant from the American Academy of Pediatrics (I.M.L), National Institutes of Health Grant T-32-DK-07729 (I.M.L), National Institutes of Health Grants UL1 RR024153 and UL1TR0000005, and grants from the American Diabetes Association (career development award to M.P.), the Renziehausen Trust Fund, and the Cochrane Webber Trust Fund (HT and DB). We also thank Susan Pietropaolo, Karen Riley, the diabetes research nurses, and the laboratory technicians for their assistance.

Abbreviations

- AA

African American

- ALR

Adiponectin Leptin Ratio

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- C

Caucasian

- CV

Coefficient of Variation

- CHP

Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh

- D0

Day 0

- D3

Day 3

- D5

Day 5

- GADAA

glutamic acid decarboxylase 65

- IAA

Insulin Autoantibody

- ICA

Islet Cell Antigen

- IR

Insulin resistance

- M3

Month 3

- TID

Type 1 diabetes

- UPMC

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Contributor Information

Natalie Hecht Baldauff, Pediatric Endocrinology, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA USA 15224.

Hala Tfayli, Pediatric Endocrinology, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA USA 15224. Currently at the American University of Beirut Medical Center, Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine.

Wenxiu Dong, Biostatistics, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, PA USA 15261.

Vincent C. Arena, Biostatistics, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, PA USA, 15261.

Nursen Gurtunca, Pediatric Endocrinology, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA USA 15224.

Massimo Pietropaolo, Division of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030.

Dorothy J. Becker, Pediatric Endocrinology, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA USA 15224.

Ingrid M Libman, Pediatric Endocrinology, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA USA 15224.

References

- 1.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Linder B, Divers J, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(17):1778–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libman IM, Pietropaolo M, Arslanian SA, LaPorte RE, Becker DJ. Changing prevalence of overweight children and adolescents at onset of insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetes care. 2003;26(10):2871–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005-20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373(9680):2027–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libman IM, Pietropaolo M, Arslanian SA, LaPorte RE, Becker DJ. Evidence for heterogeneous pathogenesis of insulin-treated diabetes in black and white children. Diabetes care. 2003;26(10):2876–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkin TJ. The accelerator hypothesis: weight gain as the missing link between Type I and Type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44(7):914–22. doi: 10.1007/s001250100548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(3):439–51. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherer PE, Williams S, Fogliano M, Baldini G, Lodish HF. A novel serum protein similar to C1q, produced exclusively in adipocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270(45):26746–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2001;86(5):1930–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galler A, Gelbrich G, Kratzsch J, Noack N, Kapellen T, Kiess W. Elevated serum levels of adiponectin in children, adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes and the impact of age, gender, body mass index and metabolic control: a longitudinal study. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies. 2007;157(4):481–9. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leth H, Andersen KK, Frystyk J, Tarnow L, Rossing P, Parving HH, et al. Elevated levels of high-molecular-weight adiponectin in type 1 diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93(8):3186–91. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pereira RI, Snell-Bergeon JK, Erickson C, Schauer IE, Bergman BC, Rewers M, et al. Adiponectin dysregulation and insulin resistance in type 1 diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2012;97(4):E642–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(5):292–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostlund RE, Jr, Yang JW, Klein S, Gingerich R. Relation between plasma leptin concentration and body fat, gender, diet, age, and metabolic covariates. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1996;81(11):3909–13. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr VA, Malide D, Zarnowski MJ, Taylor SI, Cushman SW. Insulin stimulates both leptin secretion and production by rat white adipose tissue. Endocrinology. 1997;138(10):4463–72. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soliman AT, Omar M, Assem HM, Nasr IS, Rizk MM, El Matary W, et al. Serum leptin concentrations in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: relationship to body mass index, insulin dose, and glycemic control. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2002;51(3):292–6. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.30502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanaki K, Becker DJ, Arslanian SA. Leptin before and after insulin therapy in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1999;84(5):1524–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maahs DM, Hamman RF, D'Agostino R, Jr, Dolan LM, Imperatore G, Lawrence JM, et al. The association between adiponectin/leptin ratio and diabetes type: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. The Journal of pediatrics. 2009;155(1):133–5. 5.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian SA. Racial differences in adiponectin in youth: relationship to visceral fat and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes care. 2006;29(1):51–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redondo M, Rodriguez L, Haymond M, Hampe C, Smith E, Balasubramanyam A, et al. Serum adiposity-induced biomarkers in obese and lean children with recently diagnosed autoimmune type 1 diabetes. Pediatric diabetes. 2014 doi: 10.1111/pedi.12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen-Torvik LJ, Wassel CL, Ding J, Carr J, Cushman M, Jenny N, et al. Associations of body mass index and insulin resistance with leptin, adiponectin, and the leptin-to-adiponectin ratio across ethnic groups: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Annals of epidemiology. 2012;22(10):705–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan UI, Wang D, Sowers MR, Mancuso P, Everson-Rose SA, Scherer PE, et al. Race-ethnic differences in adipokine levels: the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2012;61(9):1261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azrad M, Gower BA, Hunter GR, Nagy TR. Racial differences in adiponectin and leptin in healthy premenopausal women. Endocrine. 2013;43(3):586–92. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9797-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danadian K, Suprasongsin C, Janosky JE, Arslanian S. Leptin in African-American children. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism : JPEM. 1999;12(5):639–44. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.1999.12.5.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seo JB, Moon HM, Noh MJ, Lee YS, Jeong HW, Yoo EJ, et al. Adipocyte determination- and differentiation-dependent factor 1/sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c regulates mouse adiponectin expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279(21):22108–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumer RM, van Roomen CP, Meijer AJ, Houben-Weerts JH, Sauerwein HP, Dubbelhuis PF. Regulation of adiponectin secretion by insulin and amino acids in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2008;57(12):1655–62. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira RI, Draznin B. Inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase signaling pathway leads to decreased insulin-stimulated adiponectin secretion from 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2005;54(12):1636–43. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yki-Jarvinen H, Koivisto VA. Natural course of insulin resistance in type I diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(4):224–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607243150404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaas A, Pfleger C, Hansen L, Buschard K, Schloot NC, Roep BO, et al. Association of adiponectin, interleukin (IL)-1ra, inducible protein 10, IL-6 and number of islet autoantibodies with progression patterns of type 1 diabetes the first year after diagnosis. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2010;161(3):444–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks-Worrell BM, Greenbaum CJ, Palmer JP, Pihoker C. Autoimmunity to islet proteins in children diagnosed with new-onset diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2004;89(5):2222–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buryk MADH, Huang Y, Libman I, Arena VC, Cheung RK, Pietropaulo M, Becker DJ. 2 Year Stability of T and B cell Autoimmunity in New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) Diabetes. 2014;63(Suppl1):A426. [Google Scholar]