Abstract

Background

Lung function monitoring by spirometry plays a critical role in the clinical care of pediatric cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, but many young children are unable to perform spirometry, and the outputs are often normal even in the presence of lung disease. Measures derived from electrical impedance tomography (EIT) images were studied for their utility as potential surrogates for spirometry in CF patients and to assess response to intravenous antibiotic treatment for acute pulmonary exacerbations (PEx) in a subset of patients.

Methods

EIT data were collected on 35 subjects (21 with CF, 14 healthy controls, 8 CF patients pre- and post-treatment for an acute PEx) ages 2 to 20 years during tidal breathing and also concurrently with spirometry on subjects over age 8. EIT-derived measures of FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC were computed globally and regionally from dynamic EIT images.

Results

Global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC showed good correlation with spirometry FEV1/FVC values (r=0.54, p=0.01), and were able to distinguish between the groups (p=0.01). Lung heterogeneity was assessed through the spatial coefficient of variation (CV) of EIT difference images between key time points, and the CVs for EIT-derived FEV1 and FVC showed significant correlation with the CV for tidal breathing (r=0.47, p=0.01 and r=0.50, p=0.01, respectively). Global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC was better able to distinguish between groups than spirometry FEV1 (F-values 776.5 and 146.3, respectively, p<0.01.) The same held true for the CVs for EIT-derived FEV1, FVC, and Tidal Breathing (F-values 215.93, 193.89, 204.57, respectively, p<0.01.)

1 Introduction

Pulmonary function monitoring by spirometry plays a critical role in the clinical care of pediatric cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Many treatment decisions in school-aged children are based on spirometry results, and lung function measurements are the major clinical end points for drug trials. One such measure is forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), which is also routinely used to classify the severity of CF [1]. However, FEV1 does not provide useful information in all cases. Two issues of particular concern are that children under the age of 6 often cannot perform repeatable forced expiration maneuvers, and many pediatric CF patients maintain normal FEV1 values despite having evidence of structural lung disease [2]. This motivates a need for surrogate measures of pulmonary function suitable for all ages.

Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) is a non-ionizing functional imaging modality based on the fact that the conductivity of the tissues in the body vary significantly [3, 4], and reconstruction of these spatially and temporally dependent properties allows one to form functional images. In 2-D thoracic EIT, cross-sectional images of the chest are formed from voltage data arising from low-amplitude alternating current applied on electrodes placed around the chest. EIT-derived measures of pulmonary function are computed from EIT data collected during tidal breathing or simultaneously with spirometry.

In this work, measures derived from electrical impedance tomography (EIT) images are studied for their utility as potential surrogates for spirometry in CF patients and to assess response to intravenous antibiotic treatment for acute pulmonary exacerbations (PEx) in a subset of patients. This is the only study to consider the predictive value of EIT-derived measures pre- to post-PEx treatment. It is one of two studies of CF patients that considers a cohort of pediatric CF patients, and it includes more subjects than any other published studies on EIT on CF patients to date.

EIT has been established as a technique that shows promise for neonatal pulmonary measurement and in pediatric patients (see [5] and the references therein), monitoring pulmonary perfusion [6, 7, 8], detection of pneumothorax [9], and evaluating shifts in lung fluid in congestive heart failure patients [10]. It has been shown to provide reproducible regional ventilation and perfusion information [11, 12, 13, 14]. Regional results have been validated with CT images [15, 16, 14, 6] and radionuclide scanning [17] in the presence of pathologies such as atelectasis, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax. Correlation between measurements of changes in lung volume using EIT imaging data collected during spirometry and a pneumotachograph has been shown to be excellent [18, 19]. EIT-derived measures of heterogeneity have been demonstrated to be effective in distinguishing between healthy controls and COPD patients [20], as well as identifying age-related increases in ventilation heterogeneity. These indices have also been demonstrated to detect spatial and temporal ventilation heterogeneities in seven patients with chronic asthma imaged before and after bronchodilator inhalation [21].

EIT-derived measures of pulmonary inhomogeneity have been used in studies with a small number of CF patients to study regional lung function [22, 23, 24], multi-layer ventilation [25], regional airway obstruction [26], the effect of different breathing aids [27], and monitoring of lobectomy [28]. Differences between the maximal changes in the pulsatile and ventilation impedance signals during intervals of spontaneous breathing have been detected in CF patients versus controls [29].

In this work, 21 CF patients and 14 healthy volunteers were imaged by EIT during tidal breathing, and subjects ages 8 and up were also imaged during spirometry (lung function testing). Of the CF patients, 8 were imaged pre- and post-treatment for an acute pulmonary exacerbation (PEx). Due to electrode detachment problems during the post-treatment data collection, the data was discarded from one subject. Regional ventilation maps were used to compute global and regional EIT-derived measures of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), the ratio FEV1/FVC and a measure computed from tidal breathing difference images without averaging, denoted by Tidal Breathing. Comparisons between the global EIT-derived estimate of FEV1 and FEV1/FVC and the spirometer values are provided, assessing their correlation and the ability of each to discriminate between the four subject groups. Subject specific predictors from pre- to post-PEx treatment are also given. Coefficients of variation in the regional EIT measures of FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, and Tidal Breathing were analyzed for their ability to distinguish between the four groups and for their predictive value for pre- and post-PEx treatment. The correlations between Tidal Breathing and the PFT EIT-derived measures were also computed. This is the only study to consider the predictive value of EIT-derived measures pre- to post-PEx treatment.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study design

This is a prospective cross-sectional, observational pilot study. The data contains observations from 35 subjects (21 CF and 14 healthy volunteers). Of these, 21 subjects have data for both tidal breathing and spirometry measurements. Healthy control subjects (Group 1) ranged in age from 2 to 20 years. Data from the CF subjects were collected either during clinical stability (Group 2) or upon hospital admission for treatment of a PEx (Group 3 pre) and for the same subjects towards the end of intravenous antibiotic treatment for the PEx (Group 3 post). The characteristics of the subject groups are summarized in Table 1. To be included in the study, CF subjects must have a confirmed diagnosis of CF based on a sweat test and/or genotype and be between the ages of 2 and 21 years. Exclusion criteria for the three groups: Known congenital heart disease, arrhythmia, or history of heart failure, admission to the intensive care unit, wearing a pacemaker or other surgical implant, pregnancy, or lactation. Only subjects ages 8 and up performed spirometry, and so that is an additional criterion for the results reported here. CF subjects in Group 3 must have demonstrated at least 3 of 11 criteria for PEx [30].

Table 1.

Description of subject groups

| Healthy | CF patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 pre | Group 3 post | |

| Description | Controls | Stable CF | admitted for PEx | discharge post PEx |

| Spirometry | if ≥ age 8 | if ≥ age 8 | yes | yes |

This study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki. Data were collected at Children’s Hospital Colorado (CHCO), Aurora, CO under the approval of the COMIRB (approval number COMIRB 14-0652) with CHC and the University of Colorado Denver and the IRB of Colorado State University. Informed written parental consent and children’s informed assent was obtained from subjects under age 18, and informed written consent from subjects age 18 and up were obtained prior to participation.

2.2 Protocol

EIT data were collected using the ACE1 (Active Complex Electrode) electrical impedance tomography system [31, 32]. This system is capable of applying alternating current of amplitude up to 5.0 mA at a single discrete user-specified frequency of up to 200 kHz and measures the resulting voltage amplitude and phase with respect to the injecting current on all electrodes used at up to 30 frames/s. It has a modular design consisting of the tomograph box containing multiplexers, direct current (DC) supply regulators, a logic circuit for active electrode switch control, and the current source; cables with active electrodes that connect the tomograph to the subject or tank; 32-channel analog-to-digital (ADC) boards (two GE ICS 1640 boards each with 16 channel 24-bit 2.5 Msamples/second); a function generator (Stanford Research Systems Model DS360 Ultra Low Distortion); and a DC power supply (Mastech DC Power Supply HY3005F-3). Here, the ACE1 system was used to apply bipolar current patterns at 125 kHz on up to 32 electrodes. Bipolar current patterns are patterns in which two electrodes actively inject current of equal magnitude 180 degrees out of phase on set pairs of electrodes sequentially. Such patterns are also referred to as “skip n” patterns in the literature where n indicates the number of electrodes between the two injection electrodes. The skip 0 patterns is also referred to as the adjacent current injection pattern in EIT literature. Single-ended phasic voltages are measured simultaneously on all electrodes. One row of disposable adhesive pediatric EKG electrodes (Phillips 13951C) were placed around the circumference of the subject’s chest with an additional electrode serving as ground on the shoulder. Each electrode was 22 mm wide and 33 mm high. The number of electrodes used depended upon the circumference of the chest, with a goal of using the maximum number of electrodes up to 32, with a small space between them of not more than 1 cm, unless it would require more than 32 electrodes. The smallest subject had a chest circumference of 53 cm at the level of the electrodes, and 18 electrodes were applied. The largest subject had a chest circumference of 98 cm at the level of the electrodes, and 32 electrodes were applied. EIT data were collected during spirometry maneuvers, which were performed while the subject was standing, and during tidal breathing, collected while the subject was seated. The spirometry data was collected with the subject standing up, breathing into the spirometry tube with a clip over the nose. One to three normal breaths were taken prior to a deep inhalation followed by rapid forcible exhalation, all into the tube, with volume and flowrate measured by the spirometer. The EIT data collected during spirometry captured one or more breaths prior to the deep inhalation, the forced rapid exhalation, and one or more recovery breaths. Subjects performed spirometry several times to obtain the best repeatable spirometry output, and EIT data was collected during each of them. The best FEV1 % predicted used in the statistical analysis is the FEV1 spirometry output that was the highest % predicted, where % predicted was computed using the Global Lung Initiative equations [33, 34], and was also repeatable.

2.3 Computation of EIT-derived measures

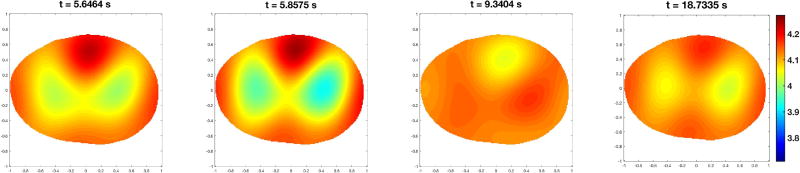

Dynamic EIT images of conductivity were computed using the 2-D D-bar method [35, 36, 37]. The D-bar method is a direct (noniterative) reconstruction algorithm in which the conductivity is computed independently at each point in the region of interest by solving several integral equations relating the data to functions known as complex geometrical optics solutions [35]. D-bar methods have been used for human data reconstruction for over a decade (see [38] for the first publications of D-bar reconstructions of human chest data), with a real-time implementation provided in [39]. In this work, the dynamic images represent changes in conductivity from a reference set of voltages which were computed by taking the average voltage for a given electrode and given current pattern over all frames in the data collection set. The conductivity in the pth pixel, denoted by σ(p), was computed for each pixel in the thorax for each frame to form the set of dynamic images. The number of pixels N in the thorax region varied depending on the subject’s shape, but in all cases was approximately N = 5900 pixels. An example of six frames from a dynamic sequence of images computed on a healthy control subject during spirometry is given in Figure 1. Conductivity changes from the average reference are displayed on a scale from blue to red, with blue representing regions with conductivity that are lower than the reference, and red representing regions of higher conductivity than the reference. Since the reference is constructed from an average voltage over all frames in the data sequence, the deep inhalation results in an image in which the lungs appear increasingly blue, due to non-conductive air filling the lung tissue. The forced exhalation results in a sequence of images in which the lungs change rapidly from blue to red. They appear red by the end of the forced exhalation because they have become more conductive than the average reference image. In the snapshots in Figure 1, the first frame is during inhalation, the second frame corresponds to peak inhalation, the third frame is at maximal exhalation, and the fourth, fifth, and sixth frames are from a subsequent breath. Conductivity changes at the top of the image are due to changes in blood flow during the cardiac cycle.

Figure 1.

Sequence of conductivity images from data collected during a pulmonary function test. Here red corresponds to high conductivity and blue to low conductivity. The images are displayed in DICOM orientation. Times in seconds elapsed since the start of the data collection are shown in the titles. The first two subfigures are frames during the deep inhalation prior to the forced exhalation. The third frame is during the forced exhalation, and the final frame is during the inhalation immediately following forced exhalation.

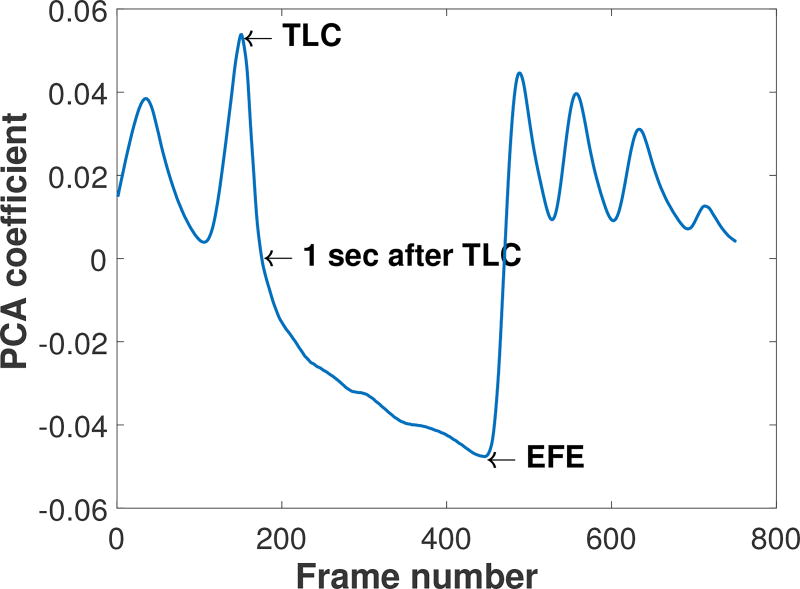

The frames in the spirometry maneuver corresponding to total lung capacity (TLC), one second after TLC (FEV1), and the end of the forced expiration maneuver (EFE) were identified from a plot of the first principal component in a principal component analysis (PCA) of the dynamic sequence of images. This approach was chosen because the first component in the PCA of the images provides a means of tracking the predominant temporal conductivity changes in the images in an easy-to-read plot with the frame number on the x-axis, which in these data sets represent changes due to ventilation. From this plot it is easy to identify frame numbers corresponding to maximum inhalation (peaks in the PCA) maximum exhalation (troughs in the PCA), and 1 sec after TLC from knowledge of the exact data acquisition rate corresponding to the number of electrodes used. An example of such a plot is found in Figure 2. The image corresponding to the TLC frame was then segmented to identify the lung region during full inspiration using a level set method with an empirical choice of threshold to ensure inclusion of the full lung region without including other organs. An example of the image segmentation on a Group 2 subject is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

PCA output for EIT data collected during spirometry on a Group 3 subject used to identify the key time points TLC, 1s, and EFE in the EIT data collection.

Figure 3.

Segmented max inspiratory EIT image from a Group 2 subject (frame TLC).

EIT-derived measures of pulmonary inhomogeneity differ slightly in the literature. In Vogt et al [20], EIT-derived measures of FEV1, FVC, and average pixel tidal volume VT were computed pixel-wise from relative impedance changes relΔZ defined by

where Zref (p) is the average impedance in pixel p during an interval of quiet tidal breathing, and Z(p) is the instantaneous impedance computed in pixel p. The average pixel tidal volume VT was calculated by identifying the inspiratory maxima and expiratory minima of the signal. Key time points in the reconstruction, which are also used in our computations, are denoted as follows.

The formulas for our EIT-derived measures are provided in section 2.3. The EIT-derived FEV1 and FVC computed from relΔZ [20] are very similar to our measure, and the method of computing the coefficient of variation (CV) is the same. The main differences are that we use an absolute, rather than a relative difference in impedance in our formulas, and instead of an average pixel tidal volume, the pixel-wise measure that we denote by Tidal Breathing is a difference image between one frame corresponding to the maximum resistivity over the time interval of tidal breathing data collection and the frame corresponding to the minimum resistivity.

The conductivity in the pth pixel for the TLC, FEV1, and EFE frames are denoted by σTLC (p), σ1s (p), and σEFE (p), respectively. At each of the time points of interest, the local volume fraction of air is computed pixel-wise using the formula derived in the context of an EIT index for regional ventilation perfusion ratios [40]. Denoting σM and σm to be the maximum and minimum conductivities, respectively, over all pixels and all frames in the data set, the volume fractions are denoted by fTLC (p), f1s (p), and fEFE (p) and are given by

These quantities range from 0 to 1. The volume Vp in liters associated with a pixel is estimated by 1000 times the area of the pixel times the electrode height in meters. In this work, all pixels had equal area (and hence volume). The EIT-derived pixel-wise measure of forced expiratory volume after one second is denoted by FEV1(p) and is given by the volume fraction difference between f1s (p) and fTLC (p) multiplied by the volume of a pixel, and FVC(p) is defined analogously:

For each pixel p in the segmented lung region the pixel-wise FEV1/ FVC ratio is given by

The EIT-derived measure FEV1/FVC(p) is a ratio of the difference in conductivity at TLC and the conductivity one second after peak inspiration to the difference in conductivity at TLC and the conductivity at the end of forced expiration. This can be computed pixel-wise, regionally by summing pixels over regions of interest, or globally by summing over all lung pixels. Note that by plotting FEV1/FVC(p), one has a single image representing the ratio of the conductivity change in each pixel at the 1s frame to that of the EFE frame, relative to the TLC frame. A global value, denoted by FEV1/FVC, is obtained by summing over all pixels in the lung region for TLC:

From the pixel-wise measures of FEV1/FVC, coefficients of variation were computed as in [20] for each measure. These coefficients provide a measure of the degree of heterogeneity in the lung region for the frame in question. For example,

The measures CVFVC and CVFEV1/FVC are defined analogously.

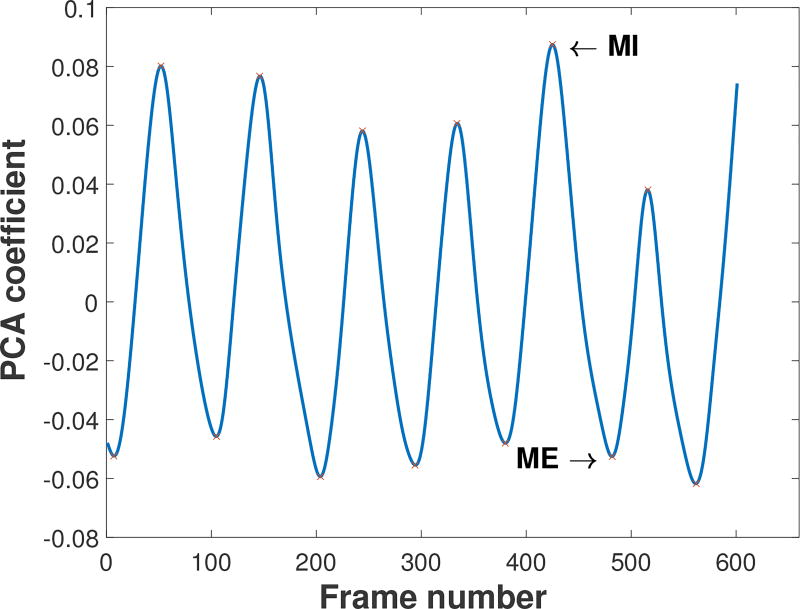

Coefficients of variation were also computed from data collected during tidal breathing. In this case the PCA from the tidal breathing reconstruction sequence was used to identify the breath with maximal conductivity difference between inhalation and exhalation. An example of such a PCA plot is found in Figure 4. Denoting the frame corresponding to maximal inspiration for the chosen breath by MI, and the frame corresponding to the moment of maximal exhalation for the same breath by ME, we define the pixel-wise conductivity change between these two frames by TidalBreathing(p):

Plotting TidalBreathing(p) results in a difference image between these two time points in the reconstructions. The corresponding coefficient of variation for TidalBreathing is

Figure 4.

PCA output for tidal breathing used to identify the key time points corresponding to maximal inhalation (MI) and maximal exhalation (ME).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Percent predicted values for FEV1 and FVC were calculated using the Global Lung Initiative equations [33, 34]. Descriptive statistics for continuous and categorical variables were compared across groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher’s exact test, respectively. A joint model was used with correlated random subject intercepts to estimate the correlation between the EIT measurements and the actual spirometry values, or the best FEV1 % predicted and the EIT-derived measure computed from the data set collected during that same spirometry maneuver, while accounting for repeated measures [41]. The correlation between the two outcomes was tested using a likelihood ratio test [42]. The least square means from this model were used to obtain comparisons of the outcomes across the groups. Single outcome mixed models were used to estimate and compare the least square means for the tidal outcomes.

Comparisons between the global EIT-derived estimate of FEV1/FVC and the spirometer values are provided, assessing their correlation and the ability of each to discriminate between the four subject groups. Subject specific predictors from pre- to post-treatment for an acute PEx are also given. Coefficients of variation in the regional EIT measures of FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, and Tidal Breathing were analyzed for their ability to distinguish between the four groups and for their predictive value for pre- and post-treatment for the PEx. The correlations between Tidal Breathing and EIT-derived FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC were also computed.

3 Results

Subject characteristics are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics

| Control (n=14) |

Group 2 (n=13) |

Group 3 (n=8) |

p-value1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (std) | 12.4 (4.9) | 9.9 (5.0) | 15.8 (3.5) | 0.05 | |

| Female, n (%) | 8 (57%) | 8 (62%) | 3 (38%) | 0.54 | |

| Genotype | |||||

| F508/F508 | 6 (46%) | 5 (63%) | |||

| F508/Other | 5 (37%) | 3 (38%) | |||

| Other/unknown | 2 (15%) | 0 | |||

| High risk genotype | 11 (85%) | 6 (75%) | |||

| FEV1 % predicted | 97.9 (14.9) (n=12) | 88.3 (28.3) (n=9) | 89.8 (15.8) (n=7) | 0.52 | |

3.1 Global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC

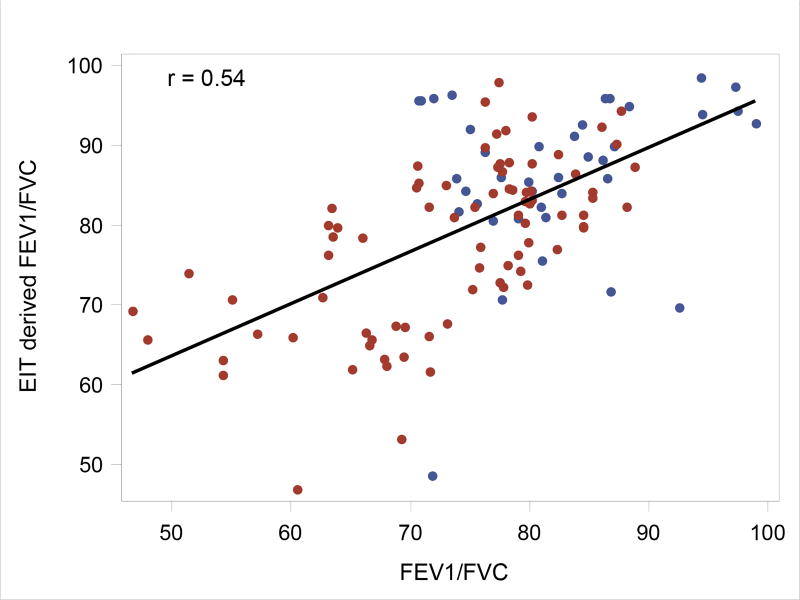

3.1.1 Comparison to spirometry values

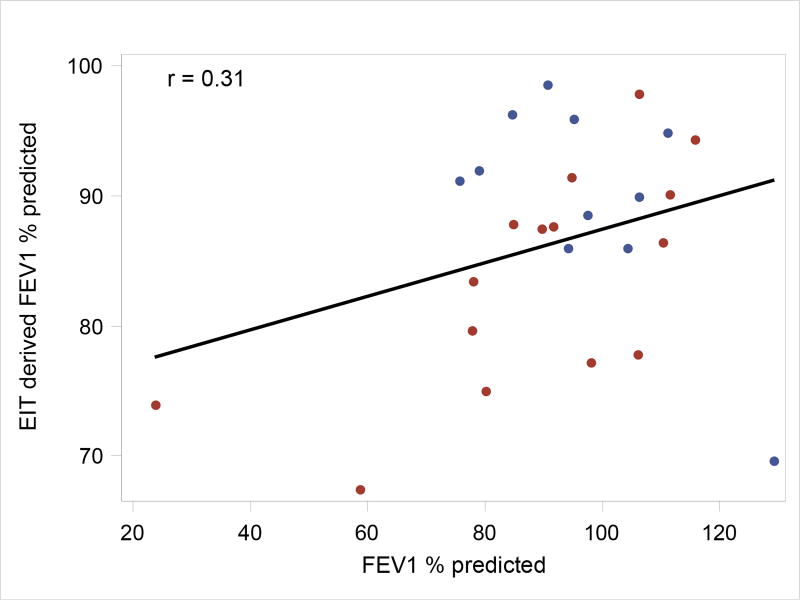

A comparison between the global EIT-derived estimates of FEV1/FVC and the actual spirometer values provides one means of validation for this EIT-derived measure of lung function. The estimated association between EIT and actual FEV1/FVC values is 0.54 (likelihood ratio test p = 0.01), and the estimated association between the best FEV1 % predicted and the corresponding EIT-derived FEV1 is 0.31 (p = 0.12). See Figures 5 and 6, respectively, for the correlation plots.

Figure 5.

Association between EIT-derived and actual FEV1/FVC. Points correspond to observed values; the black line corresponds to the correlation using all points. The blue and red points are data points from Control and CF subjects, respectively.

Figure 6.

Association between EIT and best FEV1 % predicted. Points correspond to observed values; the black line corresponds to the correlation using all points. The blue and red points are data points from Control and CF subjects, respectively.

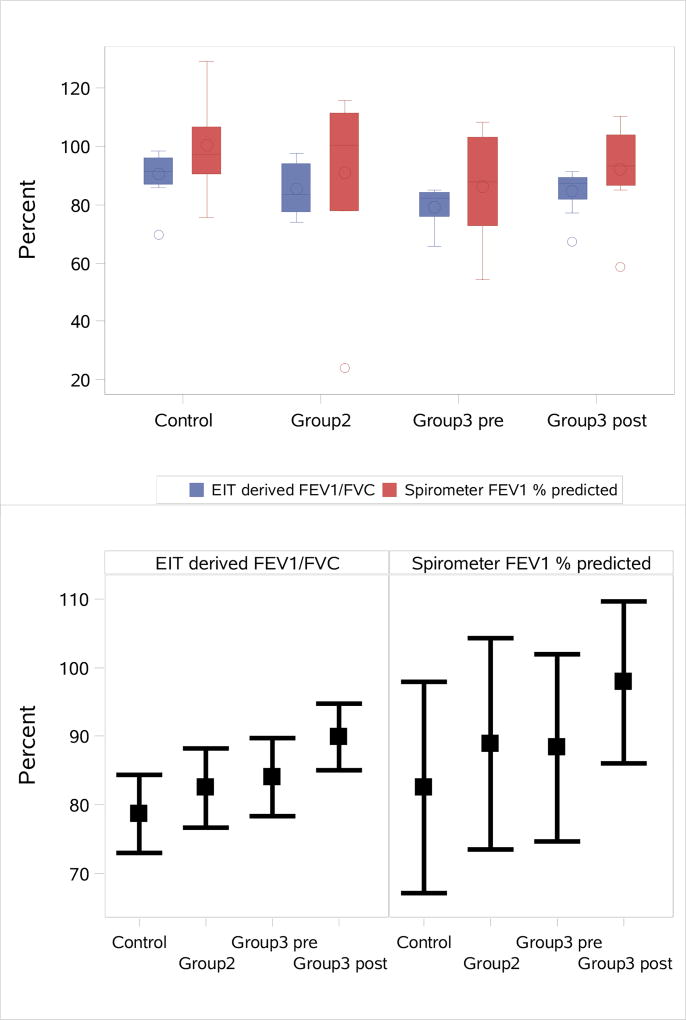

3.1.2 Ability to distinguish between disease states

The ability of the global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC to distinguish between the four subject groups Controls, Group 2, Group 3 pre, and Group 3 post was compared to that of best FEV1 % predicted. See Figure 7 for the distribution of both outcomes and the least square mean estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals across groups for both outcomes. The overall comparison across all 4 groups was statistically significant for both outcomes with p<0.01 and a better ability to distinguish between groups for the global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC outcome than for best FEV1 % predicted (EIT Fvalue=776.5, p<0.01; best FEV1 Fvalue=146.3, p<0.01). A comparison among all group pairings is found in Table 3. The EIT-derived best FEV1/FVC differentiated between the following pairs with statistical significance: controls vs CF patients, controls vs Group 3 pre, and Group 3 pre vs Group 3 post PEx. It distinguished between controls vs Group 2, controls vs Group 3 post, controls vs Group 3 pre, Group 2 vs Group 3 pre and controls vs All CF (the union of Group 2, Group 3 pre, and Group 3 post) better than the best FEV1 % predicted spirometry values.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the spirometry measurements FEV1 % predicted and global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC across groups. Top: Distribution of the observed values for both outcomes. Bottom: Least square mean estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals across groups for both outcomes.

Table 3.

Group comparisons indicating the ability of EIT-derived global FEV1/FVC and best FEV1 % predicted from the spirometer to distinguish between pairs of groups

| EIT FEV1/FVC | Best FEV1 % predicted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Group Comparison | Estimate (SE) |

p-value | Estimate (SE) |

p-value | |

| Control | Group 2 | 5.9 (3.8) | 0.13 | 9.6 (9.1) | 0.29 |

| Control | Group 3 post | 7.5 (3.8) | 0.05 | 9.1 (9.8) | 0.36 |

| Control | Group 3 pre | 11.3 (3.8) | < 0.01 | 15.4 (9.8) | 0.12 |

| Group 2 | Group 3 post | 1.6 (4.1) | 0.70 | −0.6 (10.4) | 0.96 |

| Group 2 | Group 3 pre | 5.4 (4.1) | 0.19 | 5.8 (10.4) | 0.58 |

| Group 3 post | Group 3 pre | 3.8 (0.3) | < 0.01 | 6.4 (1.2) | < 0.01 |

| Control | All CF | 24.6 (9.8) | 0.01 | 34.1 (24.6) | 0.17 |

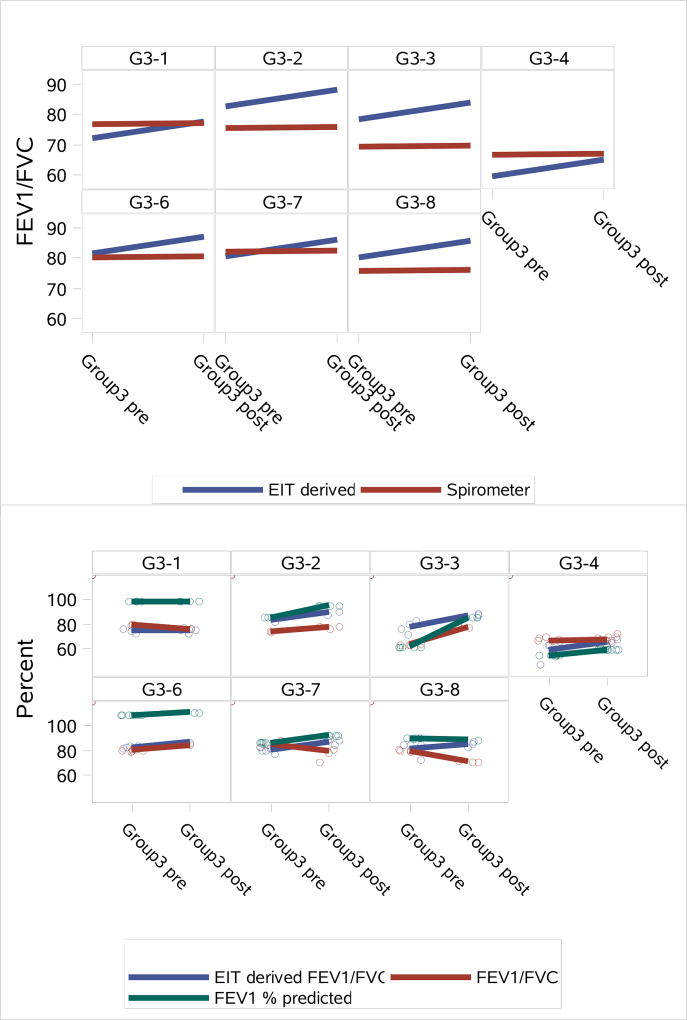

3.1.3 Subject-specific predictors pre- and post-treatment for an acute PEx

In Figure 8, change in EIT-derived global FEV1/FVC, spirometry measured FEV1/FVC and FEV1 are displayed for pre- and post-treatment for an acute PEx. Subject G3–5 was omitted due to electrode detachment problems. In each case, the EIT-derived FEV1/FVC shows improved lung function performance from pre- to post-treatment. In three cases the actual spirometry values for FEV1/FVC did not show improvement from pre- to post-treatment, and one case showed very little improvement (Subject G3–4). However, the FEV1 spirometry values show improvement or remain static (G3–1) in all cases except Subject G3–8.

Figure 8.

Subject-specific predictors showing the change in the average values for EIT-derived global FEV1/FVC and spirometry FEV1/FVC outcomes pre- and post-treatment for an acute PEx from the joint model (top), and observed values with lines connecting the means (bottom).

3.2 Regional EIT-derived measures of lung function

3.2.1 Correlations between coefficients of variation

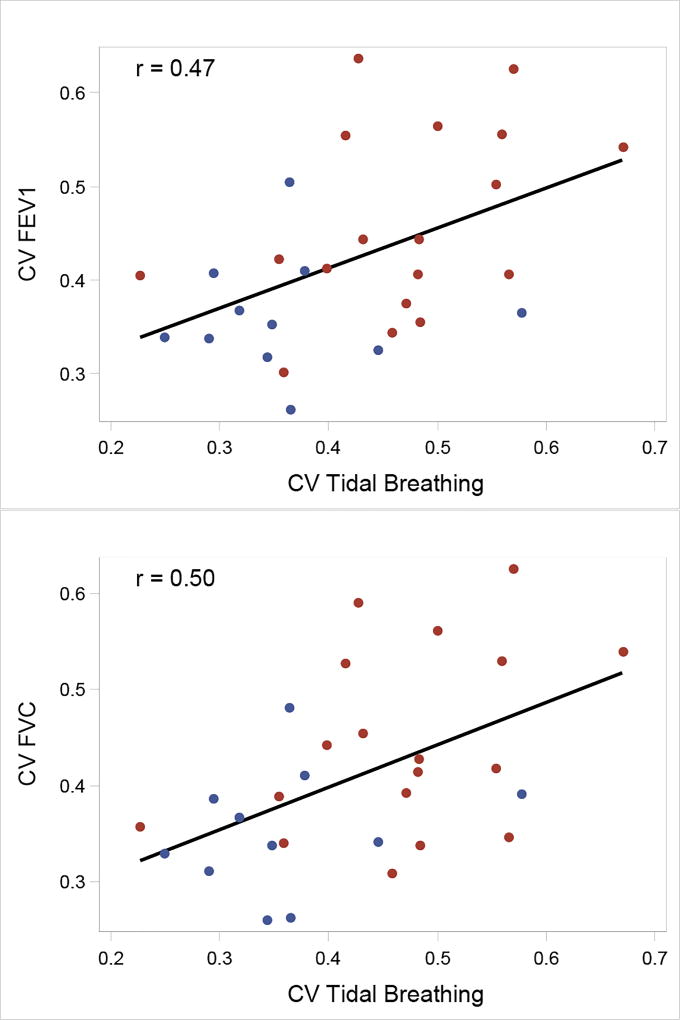

The correlations between the coefficients of variation (CV) for the EIT-derived FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC vs Tidal Breathing were computed for subjects for which data was collected during spirometry and tidal breathing (hence only subjects ages 8 and up) to assess whether the Tidal Breathing CV measure can provide the same information about the degree of heterogeneity as the CV for the spirometry measures. Since multiple spirometry tests were performed, the average value of the CV for each measure and for each test was used and compared against the single Tidal Breathing CV measure. No correlation was found between the average values for CV FEV1/FVC and CV Tidal Breathing for the 29 subjects with values for both measurements (r = −0.03, p = 0.86). There was, however, a significant correlation with the CV FEV1 and FVC values with Tidal Breathing (r = 0.47, p=0.01 and r=0.50, p = 0.01, respectively). Plots of the correlation between CV FEV1 and FVC values with Tidal Breathing are found in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Top: Association between CV FEV1 and CV Tidal Breathing. Bottom: Association between CV FVC and CV Tidal Breathing. Points correspond to observed values; the black line corresponds to the correlation using all points. The blue and red points are data points from Control and CF subjects, respectively.

3.2.2 Ability to distinguish between disease states

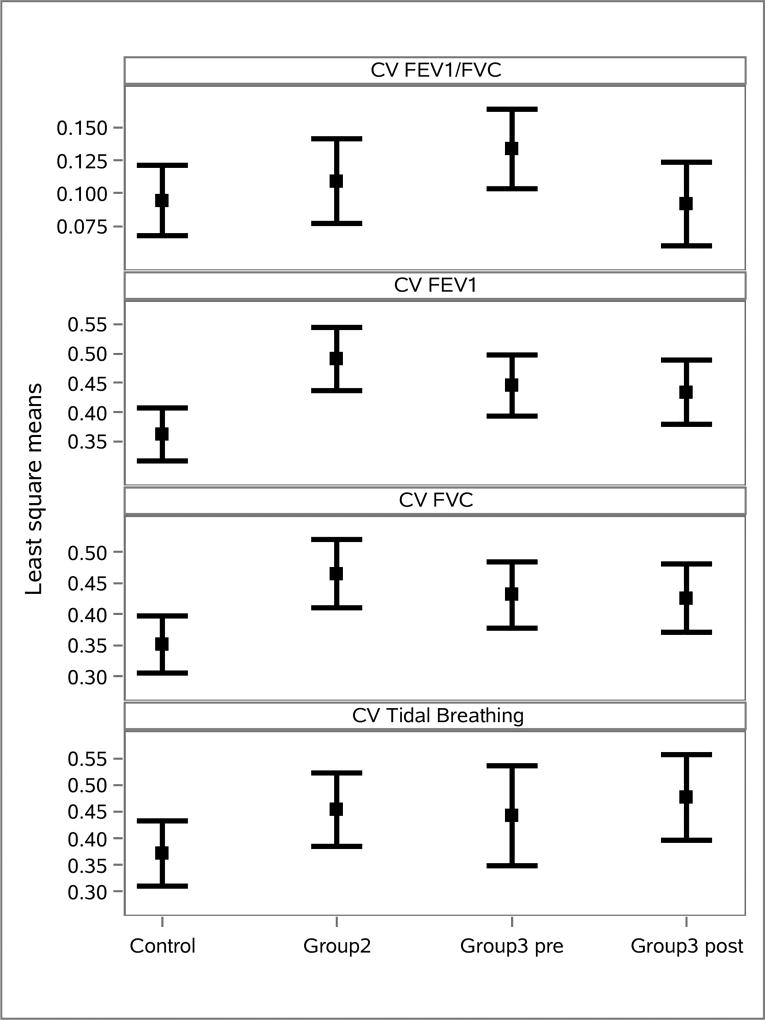

To further assess the clinical relevance of this result, the ability of each CV measure to distinguish between the four groups was studied. Figure 10 shows the least square mean values for each CV outcome across groups. The overall comparison across all 4 groups was statistically significant for all measures with p < 0.01 in all cases. The data for the four CV measures between all group pairings are found in Table 4. It can be seen from the table that the CVs for FEV1, FVC, and Tidal Breathing are more effective for distinguishing between groups than the CV for FEV1/FVC.

Figure 10.

Least square mean values for each CV outcome across groups.

Table 4.

Overall group comparisons for each of the CV outcomes

| Outcome | Degrees of Freedom (Numerator) |

Degrees of Freedom (Denominator) |

F Value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| CV FEV1/FVC | 4 | 92 | 43.46 | < 0.01 |

| CV FEV1 | 4 | 92 | 215.93 | < 0.01 |

| CV FVC | 4 | 92 | 193.89 | < 0.01 |

| CV Tidal Breathing | 4 | 6 | 204.57 | < 0.01 |

As seen in Table 5, the CVs for FEV1 and FVC showed a statistically significant ability to distinguish between the groups Control vs Group 2, Control vs Group 3 pre, Control vs Group 3 post, and Control vs CF. Tidal Breathing showed some ability to distinguish between Control vs Group 2, and the ability to distinguish between Control vs CF.

Table 5.

Group comparisons for the CVs for EIT-derived FEV1/FVC, FEV1, FVC, and Tidal Breathing measures. The comparisons for Tidal Breathing have degree of freedom equal to 6, while all others have 92 degrees of freedom. Groups 1, 2, 3 are abbreviated by G1, G2, G3 in the first column.

| FEV1/FVC | FEV1 | FVC | Tidal Breathing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Group Comparison | Estimate (SE) |

p- value |

Estimate (SE) |

p- value |

Estimate (SE) |

p- value |

Estimate (SE) |

p- value |

|

| Control | G2 | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.48 | −0.13 (0.05) | <0.01 | −0.11(0.04) | <0.01 | −0.08 (0.04) | 0.07 |

| Control | G3 post | 0.002 (0.02) | 0.91 | −0.07 (0.04) | 0.05 | −0.07 (0.04) | 0.04 | −0.11 (0.04) | 0.04 |

| Control | G3 pre | −0.04 (0.02) | 0.06 | −0.08 (0.03) | 0.02 | −0.08 (0.04) | 0.03 | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.17 |

| G2 | G3 post | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.45 | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.14 | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.32 | −0.02 (0.04) | 0.63 |

| G2 | G3 pre | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.28 | 0.05 (0.04) | 0.23 | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.39 | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.80 |

| G3 post | G3 pre | −0.04 (0.01) | <0.01 | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.50 | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.74 | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.52 |

| Control | All CF | −0.05 (0.05) | 0.33 | −0.28 (0.09) | <0.01 | −0.27 (0.09) | <0.01 | −0.26 (0.09) | 0.03 |

| Control | Stable CF2 | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.72 | −0.20 (0.06) | <0.01 | −0.19 (0.06) | <0.01 | −0.19 (0.07) | 0.03 |

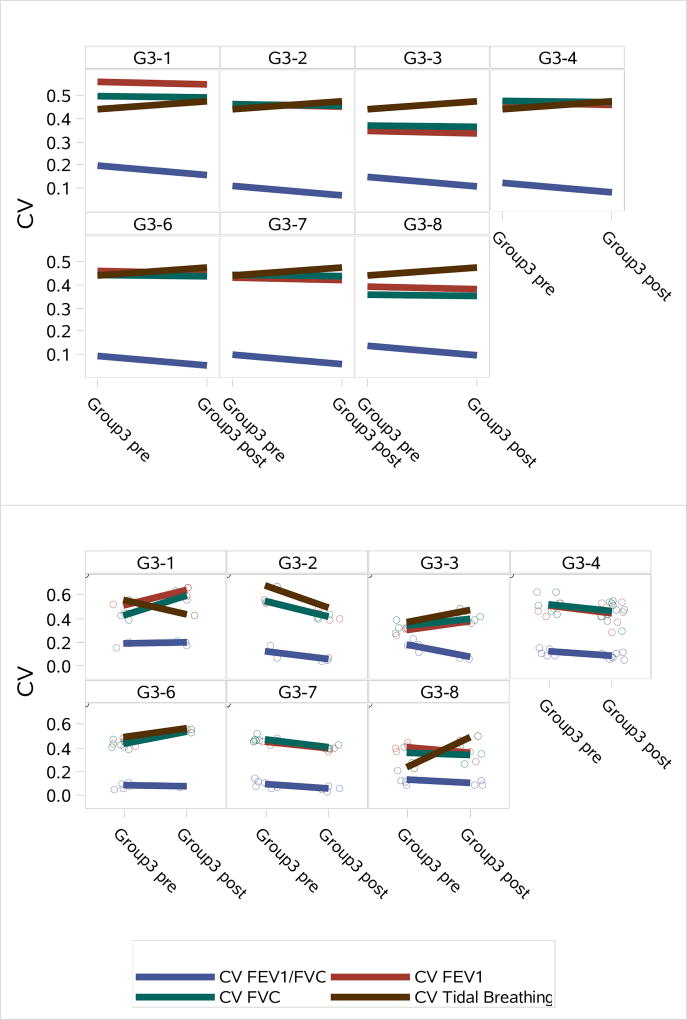

3.2.3 Subject-specific predictors pre- and post-treatment for an acute PEx

Coefficients of variation in the Group 3 subjects from pre to post PEx treatment were compared for each of the four CV measures. Figure 11 shows subject specific predictors showing the change in the average values for each CV outcome from mixed models and observed values with lines connecting the means. One would expect the CV to decrease from pre (admission) to post (discharge) since lung heterogeneity would be expected to decrease as the PEx clears.

Figure 11.

Top: Subject specific predictors showing the change in the average values for each CV outcome from pre- to post-PEx from mixed models. Bottom: Observed values with lines connecting the means.

4 Discussion

4.1 Global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC

4.1.1 Comparison to spirometry values

The results comparing global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC to spirometry output provide one means of validation for the EIT-derived measures. The good correlation between global EIT-derived FEV1/FVC and FEV1/FVC and FEV1 measured by spirometry supports the hypothesis that the global EIT measure provides an index of pulmonary performance during pulmonary function tests. In a study by Aurora et al [43], the lung clearance index derived from multiple breath washout was shown to be more sensitive than FEV1 and MEF25 in children with CF. However, in that same study, the lung clearance index also showed no correlation to FEV1 or MEF25 in the healthy children. Since the destructive pulmonary progression of CF is not uniform throughout the lung tissue, a measure of heterogeneity may be more indicative of disease progression or PEx than global spirometric measures. This non-uniformity may also contribute to a reduction in the correlation between the EIT-derived measures and spirometry, and may explain the ability of the EIT-derived measures to better distinguish between groups that was demonstrated in this study.

4.1.2 Ability to distinguish between disease states

The ability of this measure to distinguish between the four groups (healthy controls, CF patients with clinical stability, CF patients pre treatment for a PEx, and CF patients post treatment for a PEx) was better than that of the best FEV1 % predicted from spirometry (EIT Fvalue=776.5, p<0.01; best FEV1 Fvalue=146.3, p<0.01). Furthermore, it distinguished between all group pairings better than the best FEV1 % predicted spirometry values with the exception of Group 2 vs Group 3, which were indistinguishable for either outcome. The fact that Group 2 vs Group 3 post were not distinguishable for either measure is a positive finding because the Group 3 post patients had received treatment and recovered from a PEx, and had therefore returned to clinical stability.

4.1.3 Subject-specific predictors pre- and post-treatment for an acute PEx

Subject specific predictors showing the change in the average values for EIT-derived global FEV1/FVC and spirometry FEV1/FVC and FEV1 outcomes pre and post PEx treatment demonstrate the ability of the EIT measure to assess improvement in lung function. In each case, the EIT-derived FEV1/FVC shows improved lung function performance from pre to post PEx measurement, which would be expected due to the fact that the pre data was collected at the time of admission for the PEx, and the post data at the time of discharge. The improvement was not evident in the FEV1/FVC spirometry values, which did not exhibit much change from pre to post PEx treatment, but was evident in the FEV1 spirometry measures for all but two subjects, G3–1 and G3–8.

4.2 Regional EIT-derived measures

4.2.1 Correlations between coefficients of variation

The correlations between CV for EIT-derived FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC vs Tidal Breathing were computed to assess whether the CV Tidal Breathing measure can provide the same information about the degree of heterogeneity as the CV for the spirometry measures. While no correlation was found between CV FEV1/FVC and CV Tidal Breathing, a significant correlation was found between CV FEV1 and CV Tidal Breathing and between CV FVC and CV Tidal Breathing. This suggests that assessing lung heterogeneity with EIT data collected during tidal breathing merits further investigation.

4.2.2 Ability to distinguish between disease states

The utility of assessing lung heterogeneity with EIT data collected during tidal breathing was further supported by the ability of the CV Tidal Breathing to distinguish between groups, which was found to be statistically significant and comparable to CV FEV1 and CV FVC. The fact that the CVs for FEV1, FVC, and Tidal Breathing were more effective for distinguishing between groups than the CV for FEV1/FVC is likely because FEV1/FVC is computed for each pixel p by dividing FEV1(p) by FVC(p) and so variation across pixels is cancelled out to some extent, and what remains and is measured by this index is the heterogeneity in the exhalation from the FEV1 time point (frame 1s) to the end of the forced expiration maneuver (frame EFE). The CVs for FEV1, FVC, and Tidal Breathing are not computed from ratios of images, and therefore have more sensitivity to the variation in the conductivity across pixels.

4.2.3 Subject-specific predictors pre- and post-treatment for an acute PEx

The comparisons of CVs for Group 3 subjects from pre to post PEx treatment showed that mixed results in their ability to demonstrate improvement from pre to post PEx treatment, except for CV FEV1/FVC, which consistently demonstrated improvement.

4.2.4 Study limitations

Limitations to this study include the small number of patients studied pre- and post-treatment for PEx, and the high variability of the control subjects’ ability to perform repeatably pulmonary function tests. However, to the authors’ knowledge this study includes more CF patients than any published study to date using EIT on CF patients. The studies [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29] involved 14 or fewer CF patients, and the enrollment numbers are very comparable to the 7 subjects studied in this work pre- and post-treatment for a PEx. Of these references, only [23] and [28] include pediatric subjects, with [28] being a case-study of one subject who received a lobectomy. While EIT is commercially available in Europe and South America for bedside pulmonary monitoring in intensive care units, further validation is needed before it can be adopted for routine clinical use in CF. A lack of sensitivity of spirometry to early structural lung disease in CF patients is further supported by research demonstrating that abnormal CT scans and lung clearance index results are often present in children with “normal” spirometry measures [44, 45]. These studies motivate the need for more sensitive measures to detect and characterize early lung disease in CF patients, which is also advocated in the recent work by Sly and Wainwright [46]. EIT images and the derived measures of pulmonary function and heterogeneity may provide useful measures for both diagnosis and monitoring of early structural lung disease in CF patients and for life-long disease monitoring. A further limitation is the fact that the deformation of the chest due to breathing is not modeled in the reconstruction algorithm, which could improve the spatial resolution of the reconstructions and lead to improved EIT-derived measures.

5 Conclusion

This observational study provides an initial validation of EIT in CF patients by correlating EIT-derived measures of pulmonary function with spirometry, the gold standard for lung function assessment. The EIT-derived measures showed a statistically significant ability to distinguish between CF patients and healthy controls and to distinguish between different disease states in CF. Furthermore, a positive responsiveness of the EIT measures to an intervention (hospitalized treatment of a pulmonary exacerbation (PEx) with IV antibiotics) was demonstrated.

The spatial coefficient of variation provides a measure of lung heterogeneity, and was computed for the EIT-derived measures of FEV1, FVC, and FEV1/FVC and for tidal breathing. The strong correlation between the CV for Tidal Breathing and the CV for FEV1 and FVC, and the statistically significant ability of CV for Tidal Breathing to distinguish between healthy subjects and CF patients, and between the studied CF disease states suggests that the CV may be useful for measuring the extent and severity of structural lung disease, and that CV Tidal Breathing has potential to serve as a surrogate measure for spirometry in patients unable to perform them, but further studies with higher numbers of subjects are needed.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was made possible by Grant Number 1R21EB016869-01 from the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors thank Churee Pardee and Kyle Robison for recruiting the volunteers that took place in this study, and their assistance as Research Coordinators. They also wish to thank the children and families who participated in the study.

References

- 1.Davies JC, Alton EW. Monitoring respiratory disease severity in cystic fibrosis. Respiratory Care. 2012;54(5):606–617. doi: 10.4187/aarc0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiddens HA. Detecting early structural lung damage in cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2002;34:228–231. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwan H, Kay C. The conductivity of living tissues. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1957;65:1007–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1957.tb36701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuks LF, Cheney M, Issacson D, Gisser DG, Newell JC. Detection and imaging of electric conductivity and permittivity at low frequency. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1991;38(11):1106–1110. doi: 10.1109/10.99074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frerichs I, Amato MBP, van Kaam AH, Tingay DG, Zhao Z, Grychtol B, Bodenstein M, Gagnon H, Böhm SH, Teschner E, Stenqvist O, Mauri T, Torsani V, Camporota L, Schibler A, Wolf GK, Gommers D, Leonhardt S, Adler A. Chest electrical impedance tomography examination, data analysis, terminology, clinical use and recommendations: consensus statement of the TRanslational EIT developmeNt stuDy group. Thorax. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smit H, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Marcus J, Boonstra A, Vries P, Postmus P. Determinants of pulmonary perfusion measured by electrical impedance tomography. European journal of applied physiology. 2004;92(1):45–49. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlisle HR, Armstrong RK, Davis PG, Schibler A, Frerichs I, Tingay DG. Regional distribution of blood volume within the preterm infant thorax during synchronised mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(12):2101–2108. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinius H, Borges JB, Fredén F, Jideus L, Camargo ED, Amato MB, Hedenstierna G, Larsson A, Lennmyr F. Real-time ventilation and perfusion distributions by electrical impedance tomography during one-lung ventilation with capnothorax. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015;59(3):354–368. doi: 10.1111/aas.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa E, Chaves C, Gomes S, Beraldo M, Volpe M, Tucci M, Schettino I, Bohm S, Carvalho C, Tanaka H, RG L, Amato M. Real-time detection of pneumothorax using electrical impedance tomography. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(4):1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816a0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freimark D, Arad M, Sokolover R, Zlochiver S, Abboud S. Monitoring lung fluid content in chf patients under intravenous diuretics treatment using bio-impedance measurements. Physiological Measurement. 2007;28:S269–S277. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/7/S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frerichs I, Pulletz S, Elke G, Reifferscheid F, Schadler D, Scholz J, N W. Assessment of changes in distribution of lung perfusion by electrical impedance tomography. Respiration. 2009;77(3):282–291. doi: 10.1159/000193994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frerichs I, Schmitz G, Pulletz S, Schädler D, Zick G, Scholz J, Weiler N. Reproducibility of regional lung ventilation distribution determined by electrical impedance tomography during mechanical ventilation. Physiological Measurement. 2007;28:S261–S267. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/7/S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Victorino J, Borges J, Okamoto V, Matos G, Tucci M, Caramez M, Tanaka H, Sipmann F, Santos D, Barbas C, et al. Imbalances in regional lung ventilation: a validation study on electrical impedance tomography. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2004;169(7):791–800. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-133OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa E, Lima R, Amato M. Electrical impedance tomography. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2009;15:18–24. doi: 10.1097/mcc.0b013e3283220e8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frerichs I, Hinz J, Herrmann P, Weisser G, Hahn G, Quintel M, Hellige G. Regional lung perfusion as determined by electrical impedance tomography in comparison with electron beam CT imaging. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2002;21:646–652. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.800585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frerichs I, Hinz J, Herrmann P, Weisser G, Hahn G, Dudykevych T, Quintel M, Hellige G. Detection of local lung air content by electrical impedance tomography compared with electron beam CT. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;93(2):660. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00081.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunst P, Noordegraaf A, Hoekstra O, Postmus P, Vries P. Ventilation and perfusion imaging by electrical impedance tomography: a comparison with radionuclide scanning. Physiological measurement. 1998;19(4):481–490. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/19/4/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coulombe N, Gagnon H, Marquis F, Y S, Guardo R. A parametric model of the relationship between eit and total lung volume. Physiological Measurement. 2005;26:401–411. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/26/4/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marquis F, Coulombe N, Costa R, Gagnon H, Guardo R, Skrobik Y. Electrical impedance tomography’s correlation to lung volume is not inuenced by anthropometric parameters. J Clinical Monitoring and Computing. 2006;20:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s10877-006-9021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogt B, Pulletz S, Elke G, Zhao Z, Zabel P, Weiler N, Frerichs I. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of regional lung ventilation determined by electrical impedance tomography during pulmonary function testing. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012;113:1154–1161. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01630.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frerichs I, Zhao Z, Becher T, Zabel P, Weiler N, Vogt B. Regional lung function determined by electrical impedance tomography during bronchodilator reversibility testing in patients with asthma. Physiological Measurement. 2016;37(6):698. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/37/6/698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krueger-Ziolek S, Schullcke B, Zhao Z, Gong B, Moeller K. Determination of regional lung function in cystic fibrosis using electrical impedance tomography. Current Directions in Biomedical Engineering. 2016;2(1):633–636. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehmann S, Leonhardt S, Ngo C, Bergmann L, Ayed I, Schrading S, Tenbrock K. Global and regional lung function in cystic fibrosis measured by electrical impedance tomography. Physiological Measurement. 2016;51(11):1191–1199. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Z, Fischer R, Frerichs I, Müller-Lisse U, Möller K. Regional ventilation in cystic fibrosis measured by electrical impedance tomography. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2012;11(5):412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krueger-Ziolek S, Schullcke B, Zhao Z, Gong B, Naehrig S, Müller-Lisse U, Moeller K. Multi-layer ventilation inhomogeneity in cystic fibrosis. Respiratory Physiology and Neurobiology. 2016;233:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Z, Müller-Lisse U, Frerichs I, Fischer R, Möller K. Regional airway obstruction in cystic fibrosis determined by electrical impedance tomography in comparison with high resolution ct. Physiological Measurement. 2013;34(11):N107. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/34/11/N107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wettstein M, Radlinger L, Riedel T. Effect of different breathing aids on ventilation distribution in adults with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lehmann S, Tenbrock K, Schrading S, Pikkemaat R, Antink C, Santos S, Spillner J, Wagner N, Leonhardt S. Monitoring of lobectomy in cystic fibrosis with electrical impedance tomography–a new diagnostic tool. Biomedical Engineering/Biomedizinische Technik. 2012;59(6):545–548. doi: 10.1515/bmt-2014-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger-Ziolek S, Schullcke B, Gong B, Müller-Lisse U, Moeller K. Eit based pulsatile impedance monitoring during spontaneous breathing in cystic fibrosis. Physiological Measurement. 2017;38(6):1214–1225. doi: 10.1088/1361-6579/aa69d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuchs HJ, Borowitz DS, Christiansen DH, Morris EM, Nash ML, Ramsey BW, Rosenstein BJ, Smith AL, Wohl ME. Effect of aerosolized recombinant human dnase on exacerbations of respiratory symptoms and on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331(10):637–642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellenthin MM, Mueller JL, Camargo EDLB, de Moura FS, Hamilton SJ, Gonzalez Lima R. The ACE1 thoracic electrical impedance tomography system for ventilation and perfusion; Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2015. pp. 4073–4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellenthin M, Mueller J, de Camargo E, de Moura F, Santos T, Lima R, Hamilton S, Muller P, Alsaker M. The ACE1 electrical impedance tomography system for thoracic imaging. doi: 10.1109/tim.2018.2874127. In review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Report ETF. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 395-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole T, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 395 year age range: The global lung function 2012 equations: Report of the global lung function initiative (GLI), ERS task force to establish improved lung function reference values. The European respiratory journal. 2012;40(6):1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mueller J, Siltanen S. Linear and Nonlinear Inverse Problems with Practical Applications. SIAM. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siltanen S, Mueller JL, Isaacson D. An implementation of the reconstruction algorithm of A. Nachman for the 2-D inverse conductivity problem. Inverse Problems. 2000;16:681–699. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nachman AI. Global uniqueness for a two-dimensional inverse boundary value problem. Annals of Mathematics. 1996;143:71–96. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isaacson D, Mueller J, Newell J, Siltanen S. Imaging cardiac activity by the D-bar method for electrical impedance tomography. Physiological Measurement. 2006;27:S43–S50. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/27/5/S04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dodd M, Mueller JL. A real-time D-bar algorithm for 2-d electrical impedance tomography data. Inverse problems and imaging. 2014;8(4):1013–1031. doi: 10.3934/ipi.2014.8.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller P, Li T, Isaacson D, Newell J, Saulnier G, Kao T, Ashe J. Estimating a regional ventilation-perfusion index. Physiological Measurement. 2015;36(6):1283–1295. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/36/6/1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiébaut R, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Chêne G, Leport C, Commenges D. Bivariate linear mixed models using sas proc mixed. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2002;69:249–256. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikulich-Gilbertson S, Wagner B, Riggs P, Zerbe G. On estimating and testing associations between random coefficients from multivariate generalized linear mixed models of longitudinal outcomes. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0962280214568522. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aurora P, Gustafsson P, Bush A, Lindblad A, Oliver C, Wallis CE, Stocks J. Multiple breath inert gas washout as a measure of ventilation distribution in children with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2004;59(12):1068–1073. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.022590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tiddens HA, de Jong PA. Imaging and clinical trials in cystic fibrosis. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2007;4:343–346. doi: 10.1513/pats.200611-174HT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonneveld N, Stanojevic S, Amin R, Aurora P, Davies J, Elborn JS, Horsley A, Latzin P, O’Neill K, Robinson P, Scrase E, Selvadurai H, Subbarao P, Welsh L, Yammine S, Ratjen F. Lung clearance index in cystic fibrosis subjects treated for pulmonary exacerbations. European Respiratory Journal. 2015;46(4):1055–1064. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00211914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sly PD, Wainwright CE. Preserving lung function: the holy grail in managing cf. Annals of American Thoracic Society. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-254ED. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]