Persons with mental or substance use disorders or both are more than twice as likely to smoke cigarettes as persons without such disorders and are more likely to die from smoking-related illness than from their behavioral health conditions (1,2). However, many persons with behavioral health conditions want to and are able to quit smoking, although they might require more intensive treatment (2,3). Smoking cessation reduces smoking-related disease risk and could improve mental health and drug and alcohol recovery outcomes (1,3,4). To assess tobacco-related policies and practices in mental health and substance abuse treatment facilities (i.e., behavioral health treatment facilities) in the United States (including Puerto Rico), CDC and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) analyzed data from the 2016 National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS) and the 2016 National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS). In 2016, among mental health treatment facilities, 48.9% reported screening patients for tobacco use, 37.6% offered tobacco cessation counseling, 25.2% offered nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), 21.5% offered non-nicotine tobacco cessation medications, and 48.6% prohibited smoking in all indoor and outdoor locations (i.e., smoke-free campus). In 2016, among substance abuse treatment facilities, 64.0% reported screening patients for tobacco use, 47.4% offered tobacco cessation counseling, 26.2% offered NRT, 20.3% offered non-nicotine tobacco cessation medications, and 34.5% had smoke-free campuses. Full integration of tobacco cessation interventions into behavioral health treatment, coupled with implementation of tobacco-free campus policies in behavioral health treatment settings, could decrease tobacco use and tobacco-related disease and could improve behavioral health outcomes among persons with mental and substance use disorders (1–4).

SAMHSA conducts N-MHSS and N-SSATS annually among all known public and private facilities in the United States that provide mental health or substance abuse treatment services.* Survey respondents are typically facility administrators or others knowledgeable about facility operations; web-based and paper options for completion are available. In 2016, 12,745 eligible mental health treatment facilities responded to N-MHSS (response rate = 91.1%) and 14,632 eligible substance abuse treatment facilities responded to N-SSATS (91.4%). Facilities in U.S. territories, except Puerto Rico, and facilities that did not respond to one or more tobacco-related questions assessed in this report were excluded, yielding a total of 12,136 mental health and 14,263 substance abuse treatment facilities.† Descriptive statistics were assessed nationally and by state.

In 2016, tobacco screening was the most commonly implemented tobacco-related practice in mental health (48.9%) and substance abuse (64.0%) treatment facilities (Table). Cessation counseling was the most commonly offered tobacco dependence treatment in mental health (37.6%) and substance abuse (47.4%) treatment facilities. Approximately one fourth of all mental health (25.2%) and substance abuse (26.2%) treatment facilities offered NRT, and approximately one fifth of mental health (21.5%) and substance abuse (20.3%) treatment facilities offered non-nicotine medications. Approximately half of mental health (48.6%) and one third of substance abuse treatment facilities (34.5%) reported having smoke-free campuses. Among facilities with smoke-free campuses, 57.3% of mental health and 39.4% of substance abuse treatment facilities did not report offering counseling, 67.6% of mental health and 65.7% of substance abuse treatment facilities did not report offering NRT, and 74.6% and 75.8% did not report offering non-nicotine medications.

TABLE. Number and percentage of mental health and substance abuse treatment facilities that offer tobacco screening and cessation treatment and that prohibit smoking in all indoor and outdoor settings, by type of facility — National Mental Health Services Survey and National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, United States, including Puerto Rico, 2016.

| Characteristic/Location | Mental health treatment facilities* |

Substance abuse treatment facilities† |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of facilities | % Offering treatment/smoke-free campus |

No. of facilities | % Offering treatment/smoke-free campus |

|||||||||

| Screening for tobacco use | Smoking/Tobacco cessation counseling | Nicotine replacement therapy | Non-nicotine cessation medications | Smoke-free campus | Screening for tobacco use | Smoking/Tobacco cessation counseling | Nicotine replacement therapy | Non-nicotine cessation medications | Smoke-free campus | |||

|

Overall§

|

12,136

|

48.9

|

37.6

|

25.2

|

21.5

|

48.6

|

14,263

|

64.0

|

47.4

|

26.2

|

20.3

|

34.5

|

|

Facility type

| ||||||||||||

| Private for-profit |

2,152 |

41.6 |

36.3 |

24.0 |

19.7 |

39.2 |

5,044 |

54.9 |

39.1 |

19.3 |

16.3 |

22.4 |

| Private nonprofit |

7,700 |

47.0 |

34.1 |

21.1 |

17.9 |

52.8 |

7,600 |

67.5 |

50.5 |

28.0 |

20.2 |

41.3 |

| Public agency/department |

2,284 |

61.9 |

50.6 |

40.1 |

35.0 |

43.3 |

1,619 |

75.7 |

58.7 |

39.5 |

32.9 |

40.7 |

|

State

| ||||||||||||

| Alabama |

193 |

39.9 |

31.1 |

26.4 |

19.2 |

31.1 |

135 |

34.8 |

37.0 |

17.0 |

10.4 |

10.4 |

| Alaska |

99 |

57.6 |

38.4 |

22.2 |

15.2 |

67.7 |

94 |

78.7 |

54.3 |

17.0 |

13.8 |

47.9 |

| Arizona |

377 |

46.7 |

38.7 |

17.2 |

21.0 |

27.3 |

355 |

62.0 |

43.1 |

30.1 |

27.3 |

30.1 |

| Arkansas |

235 |

32.8 |

27.2 |

16.6 |

11.5 |

41.3 |

113 |

51.3 |

48.7 |

20.4 |

12.4 |

47.8 |

| California |

877 |

37.6 |

26.9 |

17.2 |

13.1 |

41.2 |

1,413 |

51.5 |

42.3 |

19.6 |

15.6 |

22.4 |

| Colorado |

185 |

55.7 |

48.6 |

32.4 |

25.4 |

61.1 |

393 |

63.6 |

45.8 |

19.8 |

17.8 |

34.1 |

| Connecticut |

230 |

52.6 |

44.8 |

33.0 |

32.2 |

57.8 |

223 |

79.4 |

55.6 |

43.5 |

35.4 |

39.0 |

| Delaware |

29 |

41.4 |

37.9 |

20.7 |

24.1 |

55.2 |

45 |

60.0 |

40.0 |

26.7 |

20.0 |

33.3 |

| District of Columbia |

41 |

46.3 |

36.6 |

14.6 |

17.1 |

51.2 |

34 |

38.2 |

32.4 |

23.5 |

17.6 |

32.4 |

| Florida |

488 |

47.1 |

35.2 |

26.8 |

19.1 |

45.7 |

706 |

55.4 |

44.8 |

33.4 |

22.8 |

28.9 |

| Georgia |

219 |

42.9 |

27.4 |

20.1 |

16.4 |

39.3 |

311 |

45.7 |

32.8 |

19.9 |

16.7 |

25.1 |

| Hawaii |

45 |

48.9 |

62.2 |

33.3 |

40.0 |

42.2 |

174 |

82.8 |

66.7 |

6.3 |

5.2 |

65.5 |

| Idaho |

176 |

24.4 |

20.5 |

10.8 |

13.6 |

19.9 |

140 |

42.1 |

30.0 |

10.7 |

15.0 |

10.0 |

| Illinois |

391 |

42.5 |

30.7 |

24.8 |

20.5 |

43.5 |

671 |

50.1 |

28.2 |

16.5 |

13.1 |

24.6 |

| Indiana |

301 |

67.8 |

56.8 |

37.5 |

35.9 |

73.8 |

262 |

69.1 |

48.1 |

26.3 |

26.0 |

59.5 |

| Iowa |

155 |

38.7 |

26.5 |

20.0 |

16.8 |

58.1 |

163 |

78.5 |

43.6 |

29.4 |

18.4 |

58.9 |

| Kansas |

119 |

35.3 |

21.8 |

21.8 |

14.3 |

44.5 |

200 |

41.0 |

33.5 |

14.5 |

14.0 |

22.5 |

| Kentucky |

221 |

41.2 |

22.6 |

16.7 |

11.8 |

34.8 |

361 |

57.1 |

26.9 |

13.9 |

9.1 |

15.8 |

| Louisiana |

186 |

54.8 |

44.1 |

37.1 |

31.7 |

43.5 |

150 |

65.3 |

49.3 |

40.7 |

24.7 |

30.7 |

| Maine |

203 |

49.8 |

36.0 |

11.8 |

11.8 |

59.1 |

228 |

72.4 |

49.1 |

21.1 |

16.2 |

46.5 |

| Maryland |

291 |

45.0 |

34.4 |

19.2 |

17.2 |

45.4 |

397 |

71.8 |

49.4 |

20.7 |

13.4 |

30.5 |

| Massachusetts |

337 |

50.1 |

39.5 |

27.6 |

21.4 |

57.3 |

351 |

87.2 |

77.5 |

43.9 |

35.3 |

34.2 |

| Michigan |

359 |

49.0 |

41.5 |

28.4 |

22.8 |

49.0 |

477 |

56.2 |

38.8 |

19.3 |

15.3 |

32.3 |

| Minnesota |

240 |

52.9 |

39.6 |

26.7 |

25.8 |

44.6 |

369 |

58.3 |

31.2 |

24.1 |

16.5 |

15.2 |

| Mississippi |

180 |

39.4 |

30.6 |

21.1 |

16.7 |

38.9 |

94 |

43.6 |

37.2 |

26.6 |

16.0 |

25.5 |

| Missouri |

219 |

59.4 |

50.7 |

42.9 |

32.9 |

55.3 |

286 |

61.9 |

44.1 |

24.5 |

19.9 |

28.3 |

| Montana |

88 |

42.0 |

25.0 |

17.0 |

17.0 |

39.8 |

64 |

50.0 |

39.1 |

29.7 |

17.2 |

26.6 |

| Nebraska |

128 |

54.7 |

32.0 |

22.7 |

18.8 |

43.0 |

136 |

61.0 |

41.2 |

26.5 |

24.3 |

35.3 |

| Nevada |

51 |

39.2 |

27.5 |

23.5 |

15.7 |

23.5 |

80 |

56.3 |

46.3 |

31.3 |

27.5 |

40.0 |

| New Hampshire |

61 |

67.2 |

50.8 |

41.0 |

32.8 |

55.7 |

64 |

78.1 |

59.4 |

34.4 |

34.4 |

37.5 |

| New Jersey |

318 |

37.7 |

37.4 |

23.6 |

20.8 |

42.5 |

368 |

67.7 |

54.1 |

24.2 |

16.3 |

29.1 |

| New Mexico |

72 |

44.4 |

34.7 |

34.7 |

19.4 |

48.6 |

153 |

60.8 |

34.6 |

22.2 |

20.9 |

34.0 |

| New York |

896 |

77.2 |

62.8 |

38.1 |

38.3 |

65.6 |

916 |

94.0 |

85.0 |

58.5 |

39.1 |

83.0 |

| North Carolina |

303 |

39.9 |

30.4 |

21.8 |

19.1 |

51.5 |

483 |

59.6 |

42.9 |

23.8 |

20.9 |

26.3 |

| North Dakota |

31 |

67.7 |

38.7 |

25.8 |

19.4 |

74.2 |

59 |

81.4 |

42.4 |

15.3 |

16.9 |

18.6 |

| Ohio |

574 |

38.9 |

31.5 |

20.0 |

15.7 |

48.3 |

398 |

60.1 |

37.4 |

28.6 |

20.9 |

30.9 |

| Oklahoma |

148 |

75.0 |

68.2 |

38.5 |

40.5 |

77.7 |

204 |

81.9 |

68.6 |

23.5 |

19.6 |

68.6 |

| Oregon |

170 |

54.1 |

39.4 |

27.6 |

21.8 |

63.5 |

221 |

89.1 |

72.9 |

27.1 |

19.5 |

56.6 |

| Pennsylvania |

586 |

51.0 |

32.4 |

24.1 |

20.3 |

42.7 |

524 |

62.0 |

40.1 |

23.3 |

16.4 |

17.9 |

| Puerto Rico |

88 |

40.9 |

44.3 |

17.0 |

20.5 |

67.0 |

140 |

41.4 |

41.4 |

13.6 |

13.6 |

34.3 |

| Rhode Island |

62 |

62.9 |

50.0 |

22.6 |

21.0 |

35.5 |

52 |

78.8 |

57.7 |

42.3 |

36.5 |

26.9 |

| South Carolina |

121 |

33.1 |

33.9 |

29.8 |

23.1 |

44.6 |

113 |

72.6 |

48.7 |

22.1 |

15.0 |

34.5 |

| South Dakota |

48 |

47.9 |

33.3 |

18.8 |

22.9 |

45.8 |

62 |

87.1 |

40.3 |

27.4 |

24.2 |

35.5 |

| Tennessee |

292 |

51.4 |

28.8 |

26.0 |

17.5 |

41.1 |

226 |

50.4 |

31.9 |

23.5 |

24.3 |

22.1 |

| Texas |

361 |

58.4 |

46.3 |

43.8 |

30.7 |

53.2 |

484 |

70.2 |

55.4 |

24.0 |

16.5 |

34.3 |

| Utah |

116 |

51.7 |

57.8 |

25.0 |

26.7 |

70.7 |

233 |

68.7 |

62.7 |

33.5 |

30.9 |

48.5 |

| Vermont |

76 |

47.4 |

46.1 |

34.2 |

32.9 |

63.2 |

46 |

93.5 |

63.0 |

54.3 |

41.3 |

69.6 |

| Virginia |

273 |

52.4 |

33.3 |

23.1 |

17.9 |

45.8 |

226 |

64.2 |

41.2 |

23.5 |

21.7 |

28.3 |

| Washington |

283 |

54.4 |

30.0 |

15.2 |

12.7 |

46.3 |

425 |

78.6 |

49.9 |

15.3 |

11.3 |

33.9 |

| West Virginia |

113 |

33.6 |

27.4 |

22.1 |

15.9 |

40.7 |

106 |

50.9 |

36.8 |

32.1 |

24.5 |

25.5 |

| Wisconsin |

430 |

37.0 |

30.9 |

15.6 |

14.0 |

47.4 |

277 |

60.6 |

47.7 |

28.9 |

30.0 |

37.2 |

| Wyoming | 51 | 58.8 | 33.3 | 13.7 | 17.6 | 51.0 | 58 | 72.4 | 72.4 | 50.0 | 34.5 | 43.1 |

* Data from National Mental Health Services Survey, 2016.

† Data from National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, 2016.

§ Does not include Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Republic of Palau, or U.S. Virgin Islands.

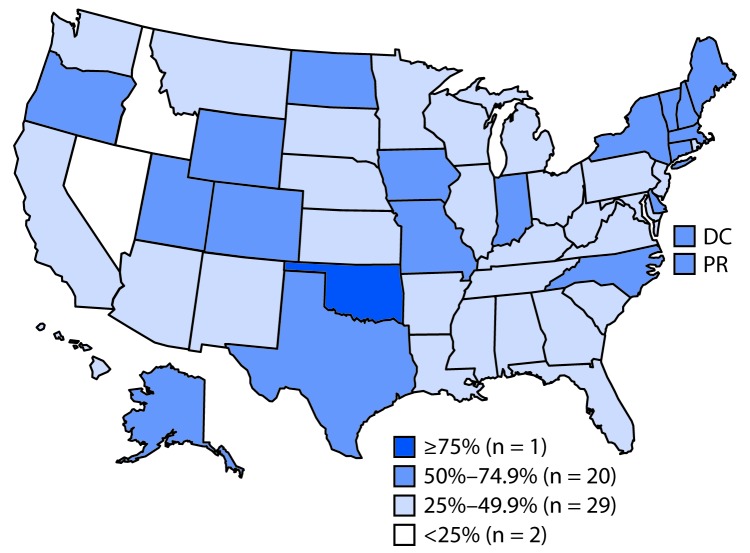

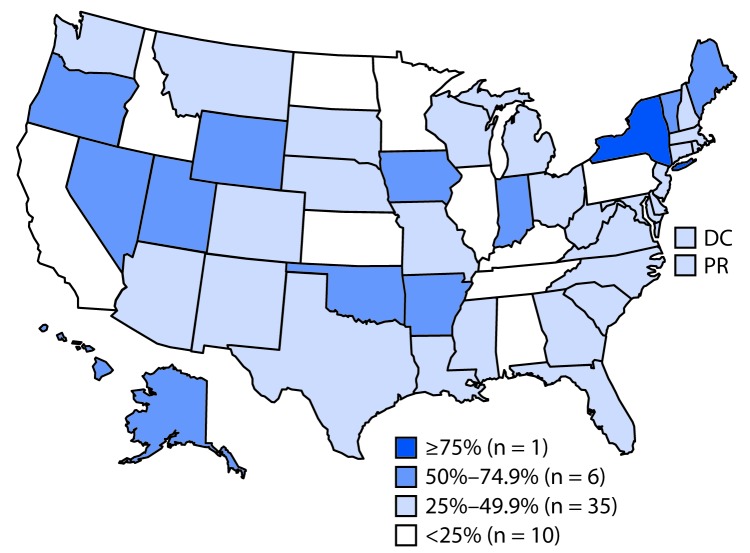

By state, the percentage of facilities offering tobacco cessation counseling ranged from 20.5% (Idaho) to 68.2% (Oklahoma) among mental health facilities and from 26.9% (Kentucky) to 85.0% (New York) among substance abuse treatment facilities. The percentage of facilities with smoke-free campus policies ranged from 19.9% (Idaho) to 77.7% (Oklahoma) among mental health treatment facilities and from 10.0% (Idaho) to 83.0% (New York) among substance abuse treatment facilities. In 31 states, fewer than half of mental health facilities had smoke-free campuses (Figure 1), and fewer than half of substance abuse facilities had smoke-free campuses in 43 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of mental health treatment facilities that prohibit smoking in all indoor and outdoor locations — National Mental Health Services Survey, United States, 2016

Abbreviations: DC = District of Columbia; PR = Puerto Rico.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of substance abuse treatment facilities that prohibit smoking in all indoor and outdoor locations — National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, United States, 2016

Abbreviations: DC = District of Columbia; PR = Puerto Rico.

Discussion

Opportunities exist to enhance both smoke-free environments and tobacco cessation treatment in mental health and substance abuse treatment settings. In 2016, fewer than half of such facilities in the United States (including Puerto Rico) offered evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments, and substantial proportions of facilities with smoke-free campus policies did not report offering tobacco cessation counseling or medications. Given that tobacco cessation in behavioral health treatment could improve both physical and behavioral health outcomes, and continued smoking worsens those outcomes, behavioral health treatment facilities are an important setting for evidence-based tobacco cessation interventions (3,4).

Several factors might contribute to the relatively low availability of evidence-based tobacco cessation treatments and smoke-free environments in behavioral health settings. First, some behavioral health treatment providers have viewed smoking cessation as a low priority relative to treatment of behavioral health conditions (2,5). Although smoking cessation could improve behavioral health outcomes (3,4), some providers are concerned that receiving smoking cessation treatment or quitting smoking during behavioral health treatment could exacerbate mental health symptoms or jeopardize substance abuse recovery (3,4). However, the latest evidence does not support these concerns (1,3,5). Notwithstanding, it is important to monitor patients during smoking cessation; for example, because smoking increases metabolism of some psychotropic medications, dosages might need to be adjusted among patients who have quit (1,3,5). Some behavioral health providers also believe that behavioral health patients who smoke are either unable or unwilling to quit (1–3). However, many smokers with behavioral health conditions want to quit smoking, are able to quit, and benefit from evidence-based smoking cessation treatments (1–3). Second, a lack of provider incentives for delivering tobacco cessation treatment, including reimbursement challenges, might pose additional barriers (5). Finally, in the past, the tobacco industry has opposed smoke-free psychiatric hospital policies, donated cigarettes to mental health facilities, and funded research suggesting that patients with psychiatric illnesses need tobacco for self-medication (1,2).

Several actions could help address actual and perceived barriers to integrating tobacco dependence treatment into behavioral health treatment. These actions could include removing administrative and financial barriers to delivery of cessation interventions and integrating tobacco screening and treatment protocols into facilities’ workflows and electronic health record systems (1,2,5). In addition, outreach to behavioral health providers could emphasize that their patients can benefit from evidence-based cessation treatments, although longer duration or more intensive cessation treatments might be indicated (1,5).

Progress has been achieved in recent years in addressing tobacco use in behavioral health treatment settings.§ For example, New York adopted regulations requiring tobacco-free campus policies in state-funded or state-certified substance abuse treatment programs and expanded Medicaid cessation benefits to allow unlimited quit attempts per year. Oklahoma improved access to treatment by eliminating copayments and prior authorization for tobacco cessation treatment for Medicaid enrollees. In addition, Oklahoma required that all substance abuse treatment facilities and state-contracted mental health treatment facilities implement tobacco-free campus policies, conduct evidence-based clinical cessation interventions, and document tobacco quitline referrals. In 2016, the Smoking Cessation Leadership Center and the American Cancer Society convened health experts, organizations, and federal agencies, including CDC and SAMHSA, to create a national action plan to reduce smoking among persons with behavioral health issues from 34% in 2015 to 30% by the year 2020.¶

The association between cigarette smoking and both substance abuse onset and relapse reinforces the importance of tobacco prevention and cessation efforts across the lifespan. Preventing tobacco use initiation might be viewed as a primary substance abuse prevention strategy because of the association between adolescent cigarette smoking and subsequent drug dependence (6). Animal models suggest that adolescent exposure to nicotine increases susceptibility to addiction to other substances (6), including alcohol, cocaine, methamphetamine (6), and opioids (7). In the current context of rising demand for opioid addiction treatment,** it is noteworthy that nicotine and opioid addictions are mutually reinforcing, whereas smoking cessation is associated with long-term abstinence after opioid treatment (8,9). In addition, cigarette smoking and chronic pain might interact in ways that might make smokers with chronic pain especially susceptible to opioid misuse (8). Therefore, efforts to increase tobacco cessation and prevent youth tobacco initiation, including during substance abuse treatment, are important components of a comprehensive strategy to prevent and reduce substance abuse.

The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, data are self-reported by facility personnel and might be subject to bias. Second, data are at the facility level rather than patient level and facilities are counted equally regardless of size, precluding estimates of individual patients’ access to cessation interventions. Finally, use of cessation treatments or implementation of smoke-free policies could not be assessed, including whether policies permit use of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products. Tobacco-free campus policies that prohibit all forms of tobacco product use, including use of e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, can support tobacco cessation, reinforce tobacco-free norms, and eliminate exposure to secondhand tobacco product emissions (6).

A comprehensive effort to reduce tobacco-related disparities among persons with behavioral health conditions includes clinical cessation interventions, as well as population-level measures to reduce the appeal, accessibility, and social acceptability of tobacco use outside the clinical context (1). Proven interventions, including raising tobacco prices, implementing comprehensive smoke-free laws, conducting media campaigns, and providing barrier-free access to proven cessation treatments, are critical to reduce smoking-related disease and death in the United States (1,6).

Summary.

What is already known about this topic?

Many persons with mental or substance use disorders who smoke want to and can quit smoking.

What is added by this report?

In 2016, among mental health facilities, 49% screened patients for tobacco use, 38% offered tobacco cessation counseling, and 49% had smoke-free campuses; corresponding estimates for substance abuse facilities were 64%, 47%, and 35%, respectively. Approximately one in four behavioral health treatment facilities offered nicotine replacement therapy; one in five offered non-nicotine cessation medications.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Tobacco-free campus policies and integration of tobacco cessation interventions in behavioral health treatment facilities could decrease tobacco-related disease and death and could improve behavioral health outcomes among persons with mental and substance use disorders.

Acknowledgments

Elizabeth Hoeffel, Xiang Liu, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts of interest were reported.

Footnotes

N-MHSS: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2016_National_Mental_Health_Services_Survey.pdf. N-SATSS: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2016_NSSATS.pdf. Excluded for N-MHSS were facilities whose client counts were included in other facilities’ counts and whose facility characteristics were not reported separately and facilities that provided administrative services only. Excluded for N-SSATS were nontreatment halfway houses, solo practices not approved by the state agency for inclusion, and facilities that treated incarcerated clients only.

This report does not include data collected from the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, the Republic of Palau, or the U.S. Virgin Islands because they are not reported separately by N-MHSS and N-SSATS.

References

- 1.Prochaska JJ, Das S, Young-Wolff KC. Smoking, mental illness, and public health. Annu Rev Public Health 2017;38:165–85. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness—United States, 2009–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62:81–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compton W. The need to incorporate smoking cessation into behavioral health treatment. Am J Addict 2018;27:42–3. 10.1111/ajad.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Breslau N, Hatsukami D, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with lower rates of mood/anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Psychol Med 2014;44:2523–35. 10.1017/S0033291713003206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeder SA, Morris CD. Confronting a neglected epidemic: tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Annu Rev Public Health 2010;31:297–314. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services. Health effects of e‑cigarette use among U.S. youth and young adults [chapter 3]. In: E-cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2016:97–126. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/e-cigarettes/pdfs/2016_sgr_entire_report_508.pdf

- 7.Klein LC. Effects of adolescent nicotine exposure on opioid consumption and neuroendocrine responses in adult male and female rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;9:251–61. 10.1037/1064-1297.9.3.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon JH, Lane SD, Weaver MF. Opioid analgesics and nicotine: more than blowing smoke. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2015;29:281–9. 10.3109/15360288.2015.1063559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mannelli P, Wu LT, Peindl KS, Gorelick DA. Smoking and opioid detoxification: behavioral changes and response to treatment. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:1705–13. 10.1093/ntr/ntt046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]