Abstract

Background

Despite national policy guidelines advocating exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life to promote and accelerate child survival, the proportion of women exclusively breastfeeding for the first six months has remained small.

Objective

To describe the knowledge and practices of mothers regarding exclusive breastfeeding in a semi-urban Ugandan population.

Design

A descriptive cross-sectional study.

Setting

Semi-urban Ugandan population in four parishes in Adjumani District, the West Nile region of Uganda.

Subjects

The breastfeeding mothers with infants aged 3–12 months.

Results

Of the 385 breastfeeding mothers surveyed, 62.6% (241/385) and 53.5% (206/385) knew the exact meaning and the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding respectively. Nearly 68.6% (264/385) initiated breastfeeding within one hour after delivery and only 42.1% (162/385) exclusively breastfed their babies in the first six months of life. For the mothers who initiated non-breast milk feeds before the first six months of birth, most stated the following reasons: ‘advice from the home’, ‘did not know the appropriate time’, baby got thirsty and baby was crying at the sight of food’.

Conclusion

This study revealed low levels of knowledge and practice of the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding among the breastfeeding mothers. Continuous breastfeeding awareness campaigns are needed to improve knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among breastfeeding mothers.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommend that every infant should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life, with breastfeeding continuing for up to two years of age or longer (1). Breast milk is uncontaminated, remains a “superior food” for babies and it contains optimal amounts of fats, sugar, water and protein needed for their growth and development which is necessary for children in the first few months of life (2,3).

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), which is giving breast milk only and no other liquids, except drops or syrups with vitamins, mineral supplements or medicines in the first six months of life, is superior to non-exclusive breastfeeding and have a protective effect against both morbidity and mortality (4,5). It is estimated that sub-optimal breastfeeding, especially non-exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life, results in 1.4 million deaths and 10% of diseases in under-fives. It can also increase the risk of dying due to diarrhoea and pneumonia among zero to five month old infants by more than two-fold (2).

Promotion of exclusive breastfeeding is the single most cost-effective intervention to reduce infant mortality in developing countries (2,6,7). However, many mothers continue to use other feeds in addition to breastfeeding in the first six months after birth. The aim of this study was to gather information on the level of knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among breastfeeding mothers in Adjumani District in the West Nile Region of Uganda.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study. Breastfeeding mothers with infants aged 3–12 months in four parishes in Adjumani District were consented and recruited into the study. Interviewer administered survey questionnaires were used to collect quantitative data. Adjumani town council and Pakele sub-county were purposely selected; two parishes were randomly selected from each of the two sub counties; Biyaya and Cesia parishes from town council, Pereci and Pakele town board from Pakele sub-county. In each parish, a sample of 96 breastfeeding mothers (25% of the total sample size) who were available at home at the time of interview were recruited consecutively through house-to-house visit starting at the nearest household to the parish Centre, then to the nearest neighboring household until the required size was realized.

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from St. Mary’s Hospital, Lacor institutional and ethical review committee. The sample size estimated using Keish and Leslie sample size estimation method was 385.

The main variables of the study were respondents’ knowledge level and practices of exclusive breastfeeding. Data on other factors influencing practices of exclusive breastfeeding such as age, sex, level of education, marital status, ANC visits, post-natal care visits were obtained.

Quantitative data were analyzed by use of SPSS 16.0.

RESULTS

A total of 385 respondents were interviewed and analyzed. Of the respondents, 89.9% (346) were aged 18–35 years, 94.5% (364) were married, 95.8% (369) attended a formal education and 63.9% (246) were house wives by occupation. About 75.1% (289) lived within four kilometres from the nearest health facility and all mothers lived within ten kilometres from the nearest health facility (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the study participants.

| Variable | Category | Frequency, N=385 | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of breastfeeding mothers/years | 14 – 17 | 10 | 2.6 |

| 18 – 35 | 346 | 89.9 | |

| 36 – 49 | 28 | 7.3 | |

| Don’t remember | 1 | 0.3 | |

|

| |||

| Marital status | Single | 21 | 5.5 |

| Married | 337 | 87.5 | |

| Separated, Divorced or Widower | 27 | 7.0 | |

|

| |||

| Education level | Uneducated | 16 | 4.2 |

| Primary education | 220 | 57.1 | |

| Secondary education | 108 | 28.1 | |

| Tertiary education | 41 | 10.6 | |

|

| |||

| Occupation | Student | 12 | 3.1 |

| House wife | 246 | 63.9 | |

| Self employed | 102 | 26.5 | |

| Government employed | 10 | 2.6 | |

| Private employed | 15 | 3.9 | |

Age distribution of the babies was as follows: 3–6 months, 126 (32.9%); 7–9 months, 89(23.2%); and 10–12 months, 168 (43.9%).

Knowledge of exclusive breastfeeding

Out of the respondents, 80.8% (311/385) had ever been taught exclusive breastfeeding. Of these 95.8% (298/311) were taught by the health workers and 93.2%(290/311) were taught at the time of ante-natal and post-natal care visits. One-quarter (79/311), however felt the teachings were not clear.

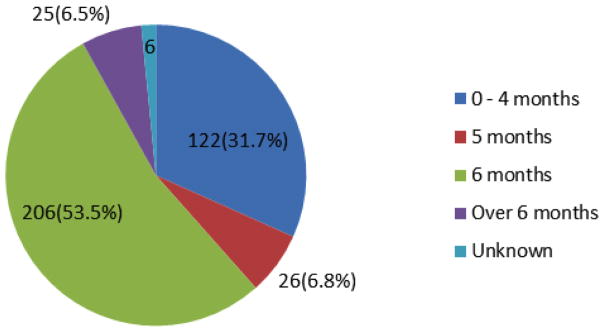

Of all the respondents, 62.6% (241/385) knew the exact meaning of exclusive breastfeeding and 53.5% (206/385) knew the recommended duration of exclusive breast feeding. Figure 1 shows the different opinions of the mothers on the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

Figure 1.

Mothers’ opinions on the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding.

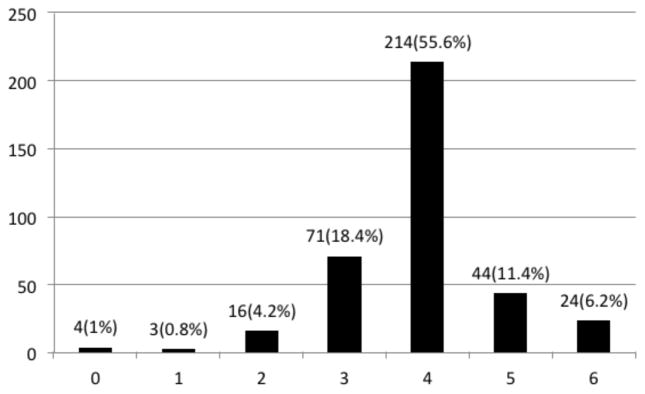

Ante-natal care attendance was nearly universal. As shown in figure 2,99.0% (381) attended ante-natal care services at least once, with 94% of the mothers making three or more ante-natal visits for their current baby’s pregnancies. Delivery in a health facility and post-natal care attendance was also very high, with 95.3% (367) delivered at the health facilities and 97.7% (376)attending post natal care services. Only 2.3% (9) never attended post-natal care services.

Figure 2.

Bar graph representing number of ante-natal care visit attendance.

Practice of exclusive breastfeeding

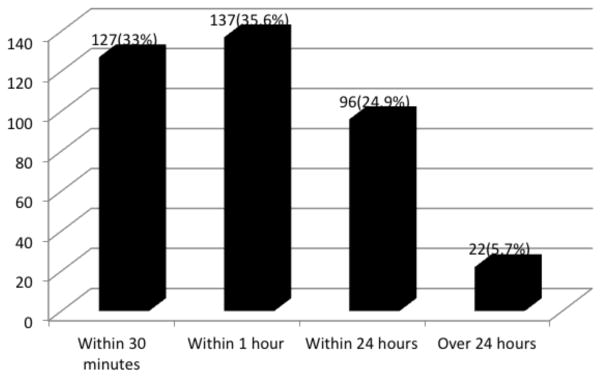

Out of the mothers surveyed, 42.1% (162/385) exclusively breastfed their infants for the first six months; of those breast-fed babies, 68.6% (264/385) initiated breastfeeding within one hour of delivery and 82.9 %(319/385) of the mothers gave only breast milk to their babies in the immediate post-partum period (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time duration taken to initiate breastfeeding after delivery.

For the mothers who initiated breastfeeding after one hour of birth, most stated the following reasons: ‘I had no breast milk’, ‘baby was unable to suck’, ‘I was sick’, ‘I was too tired to breast feed immediately after delivery’.

Most respondents who gave non-breast milk feeds to their babies before the first six months stated the following reasons which include; ‘advice from the home and relatives (grandmother, husband)’, ‘did not know the appropriate time’, ‘baby crying at the sight of food’, ‘I am very busy to breast feed’, ‘I wanted baby to learn to eat early’.

DISCUSSIONS

This study aimed to assess the level of knowledge and practices of exclusive breastfeeding among breastfeeding mothers in a rural Ugandan Town. The World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommend that every infant should be exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life, with breastfeeding continuing for up to two years of age or longer (1). In this study, it was notable that 43.9% of the mothers still breastfed their infants at 10–12 months, a practice that is worth encouraging and promoting through young child clinics or baby well clinics. The majority of the mothers (89.9%) were aged 18–35 years indicating the most fertile reproductive age group as compared to only 7.3% (28) of the mothers above 35 years who were still producing and breastfeeding their babies. This is in conformity to a previous study in Ethiopia (8,9). Of the mothers surveyed, 4.2% never attended formal education. This is consistent to a previous study done in Ethiopia (10). This may be because both studies were carried out in a rural setting. Nearly two-thirds(63.9%) of the mothers surveyed were house wives by occupation compared to only 33% (137) who were employed with either the government, private institutions or self-employed. This finding is similar to previous studies in Ethiopia (8,10). Majority of the mothers, 75.1% lived within four kilometres from the nearest health facility. This is congruous with the ministry of health (MOH) of Uganda recommendation of a distance of not more than five kilometres to the nearest health facility in order to improve access to health care services aiming at reducing childhood mortality.

Our study revealed that most women, 80.8% of the study population, had the opportunity to learn about exclusive breastfeeding with the majority (95.8%) being taught by health workers from ante-natal and post-natal care visits. This is in line with a previous study in South Nigeria (9) whereas in a similar study conducted in South India, (11) majority of the mothers (52%) did not receive any advice on breastfeeding during ante-natal period, 31% received from parents and relatives and only 17% received advice from health care workers. This might be due to the fact that in the current study, almost all mothers have attended both ante-natal and post-natal care and majority admitted being taught exclusive breastfeeding by health workers during those visits.

Despite the fact that almost every woman had the opportunity to learn about exclusive breastfeeding in the present study, only 62.6% of the mothers knew the exact meaning of exclusive breastfeeding which is lower than for studies carried out in a rural population in south Eastern Nigeria, 87.0%(12) and a community based cross sectional study done in Ethiopia, 90.8%(13). This could be due to the unclarity of the teachings as reported in the present study by one-quarter of the respondents. This current finding is higher than for a previous study done in Kware, Nigeria with 54(31%)(14) of the mothers had adequate knowledge of exclusive breastfeeding.

The breastfeeding mothers in the current study had also posed lower knowledge on the duration of exclusive breast feeding as about one-half (53.5%) knew the duration of exclusive breast feeding compared to a similar study conducted in Mbarara hospital where a majority of the respondents 150 (73.8%)(15) were knowledgeable about the duration of exclusive breast feeding. The difference could be due to our study being a community based as compared to the previous study which was a hospital based. This knowledge of recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding in the present study was higher than for a similar study in south India, where (38%)(11) knew the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding. This could be explained by the fact that the majority of mothers in the present study had opportunity to learn about exclusive breastfeeding whereas in a previous study done in India (11), majority did not receive information on exclusive breastfeeding during ante-natal care.

From our study, 42.1% of the respondents exclusively breastfed their infants for six months which was slightly lower than for previous studies in Mbarara hospital, 49.8%(15), Kawampe 56.3%(16) and Nigeria 63.0% (12), crital lower than for a previous study in Ethiopia, 82.2%(13)however it was slightly higher than for previous studies in Mozambique 37.0% (17), Kware 31% (14) and Uganda 39% (18). Our study revealed low prevalence of exclusive breast feeding which was similar to other studies above however in all the studies, the prevalence of exclusive breast feeding were below the global and National recommended level.

In the current study, one-third of the mothers who were eager to breastfeed initiated within 30 minutes of delivery and about two-third (68.6%) initiated within one hour as recommended by WHO this is consistent to the previous study in Kware, Nigeria 53% (14). Of the mothers who delayed at least one hour after delivery to initiate breast feeding, most of them stated the following reasons which includes: I had no breast milk, baby was unable to suck, I was sick, I was too tired to breast feed immediately after delivery. These findings are similar to another study done in India, (11).

Our study revealed that breast milk remains the main feeds in the immediate post-partum period as majority, 82.9% of the mothers gave breast milk only to their babies as compared to 17.1% who gave in addition to breast milk, sugar, water, juice, honey, soup, porridge or cow milk corresponding to a study done in Mozambique (17). Most respondents who gave non-breast milk feeds to their babies before the first six months stated the following reasons which include; ‘advice from the home and relatives (grandmother, husband)’, ‘did not know the appropriate time’, ‘baby crying at the sight of food’, ‘I am very busy to breast feed’, ‘I wanted baby to learn to eat early’.

These findings are similar to a previous study in Mbarara hospital, (15) suggesting multi-disciplinary approaches is required to improve on the level of knowledge and practices of exclusive breast feeding in rural settings.

In conclusion, The level of knowledge and practices of exclusive breastfeeding among breastfeeding mothers in Adjumani District is below the national and global recommendation.

We recommend continuous breastfeeding awareness campaigns are needed to improve knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among breastfeeding mothers.

There is need for continuous education of mothers with improved clarity of the teachings on exclusive breastfeeding.

Since almost all mothers learnt about exclusive breast-feeding at ante-natal and post-natal care visits, additional mass media on exclusive breastfeeding might capture mothers who do not attend those visits and also to prepare them before conception.

STUDY LIMITATION

Knowledge, beliefs and practices of cultural leaders and men who are part and key partners in delivering exclusive breastfeeding is beyond the scope of this study. This being a cross sectional study, the future level of knowledge and practices of exclusive breast feeding is beyond our scope.

Acknowledgments

To the mothers in Adjumani District who participated with their infants in our study. We also thank Adjumani District Administration officials and local administrative units in Pakele sub-county and Adjumani town council.

This work was made possible by Medical Education for equitable services to all Ugandans, a Medical Education Partnership Initiative; grant number R24TW008886I from the office of Global AIDS Coordinator and the U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration and National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

A.P. Adrawa, Medical Student, Gulu University

D. Opi, Medical Student, Gulu University

E. Candia, Medical Student, Gulu University

E. Vukoni, Medical Student, Gulu University

I. Kimera, Medical Student, Gulu University

I. Sule, Medical Student, Gulu University

G. Adokorach, Medical Student, Gulu University

T.O. Aliku, Faculty of Medicine, Gulu University

E. Ovuga, Faculty of Medicine, Gulu University

References

- 1.World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland. Community-Based Strategies for Breastfeeding Promotion and Support in Developing Countries. (updated 2003) Available from http://www.Linkagesproject.org/media/publications/Technical20Reports/CommunityBFStrategies.Pdfwebcite.

- 2.World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) Model Chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO & UNICEF. Breastfeeding Counseling: a training course. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: A systematic review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:63–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4242-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.León-Cava N, Lutter C, Ross J, Martin L. Quantifying the Benefits of Breastfeeding: A Summary of the Evidence. Washington, USA: The Food and Nutrition Program (HPN), Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), The Linkages Project; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Plessis D. Breastfeeding: mothers and health practitioners, in the context of private medical care in Gauteng. J Interdiscipl Health Sci. 2009;14:1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fjeld E, Siziya S, Katepa-Bwalya M, et al. PROMISE-EBF Study Group. No sister, the breast alone is not enough for my baby’ a qualitative assessment of potentials and barriers in the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in southern Zambia. Int Breastfeeding J. 2008;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tewodros A, Jemal H, Dereje H. Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2009;23:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aniekan MA, Etiobong, Etukumana A, Nyong Eno, Ukeme EE. Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among ante-natal attendees in Uyo, Southern Nigeria. Gaziantep Med J. 2014:130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tesfaye S, Tefera B, Mulusew G, Kebede D, Amare D, Sibhatu B. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding practices among mothers in Goba district, southeast Ethiopia. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2012;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-7-17. http://www.internationalbreastfeedingjournal.com/content/7/1/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maheswari E, Vishnu BB, Ahamed Mohamed Asif Padiyath. Knowledge attitiude and practice of breastfeeding among post-natal mothers. Curr Pediatr Res. 2010;14:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agu U, Agu MC. Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in a rural population in south eastern Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Medical Research. 2011;15(2) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenebu BB, Belayneh KG, Alayou G, Ahimed A, Bereketchinasho Abreham A, Amanuel Y, Keno T. Knowledge and Practice of mothers towards exclusive breastfeeding and its associated factors in Ambo Woreda West Shoa Zone Oromia region, Ethiopia. International journal of medical sciences and Pharmaresearches. 2015;1(1) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oche MO, Umar AS, Ahmed H. Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding in Kware, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11:518–523. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ampeire IP. Perception and knowledge on exclusive breastfeeding among women attending ante-natal and post-natal clinics. A study from Mbarara hospital–Uganda. Dar Es Salaam Medical Student’s Journal. 2008;16:29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oyang W. Prevalence and factors affecting exclusive breastfeeding among mother-infant pairs in Kawempe Division, Kampala District. 2008 URI: Makerere University Institutional Repository collection. home page. http://hdl.handle.net/10570/218.

- 17.Arts M, Geelhoed D, De Schacht C, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, and practices regarding exclusive breastfeeding of infants younger than 6 months in Mozambique: a qualitative study. J Hum Lact. 2011;27:25–32. doi: 10.1177/0890334410390039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Preliminary report. Uganda Bureaus of Statistics (UBOS); Kampala Uganda: 2011. Uganda Health Demographic Survey 2011. Internet: http://www.ubos.org. [Google Scholar]