Abstract

Background/Aims

We aimed to investigate whether the current indications for curative endoscopic resection (ER) of gastric cancer (GC) can be applied to GC caused by adenoma. Additionally, we attempted to identify factors predictive of lesions subsequently found in addition to the expanded indications for ER.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 342 patients diagnosed with GC caused by adenoma who underwent ER at a single tertiary center between February 2011 and December 2014. The gross whole tumor size was measured using the endoscopically resected specimen. The microscopic whole tumor size was measured using mapping paper. The estimated cancer size was calculated using the microscopic whole tumor size and the square root of the carcinoma component.

Results

A gross whole tumor size ≥3 cm, carcinoma component ≥35%, and gross ulceration were predictive of lesions other than the expanded indications for ER. The overall rate of lymph node metastasis was 0.3% (1/327), which only occurred in one patient with a lesion other than the expanded indications (4.5%, 1/22).

Conclusions

The current indications for curative ER in GC can be applied to GC caused by adenoma. In cases suspected of having lesions other than the expanded indications, patients should be cautiously selected for ER to reduce the risk of an inappropriate procedure.

Keywords: Upper gastrointestinal track, Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, Endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Gastric adenoma is a premalignant lesion.1 Although the risk of progression from adenoma to gastric cancer is relatively low,2,3 adenomas can progress to invasive carcinoma4 or even advanced gastric cancer.3 Endoscopic forceps biopsy is the gold standard for histological diagnosis of adenoma before endoscopic resection (ER). However, the histological discrepancy rate between the results of biopsy specimens and those obtained at ER was noted to be considerably high in recent studies.5–8 Reportedly, 6.4% to 30.1% of biopsy-diagnosed low-grade adenomas are finally diagnosed as high-grade ones and 3.8% to 11.0% as adenocarcinomas after ER.5,9 ER for early gastric cancer (EGC) is currently the established treatment of choice because it both minimally invasive and effective as a curative procedure for EGC.10,11 Recently, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) has been developed to improve the en bloc resection rate over that of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR).12 ESD is performed for EGC lesions meeting the expanded indications for ER.13,14 Patients with EGC who undergo treatment based on the expanded indications have been reported to have similar long-term survival and outcomes to those treated according to the earlier absolute indications.15 However, if ER is performed and the lesion is subsequently found to be beyond the expanded indications, patients require additional treatment such as surgery. Thus, accurate prediction prior to ER of which EGC lesions will be found to be beyond the expanded indications could help physicians determine an appropriate treatment strategy and avoid unnecessary procedures. To the best of our knowledge, the criteria for evaluation of curative ER of gastric cancer arising from adenoma are rarely reported. Factors that might predict which lesions are actually beyond the expanded indications after ER are also rarely reported. This study was conducted to evaluate whether the current criteria for curative ER for EGC can be applied to gastric cancer arising from adenoma and to identify factors that can predict which lesions are beyond the expanded indications for ER.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

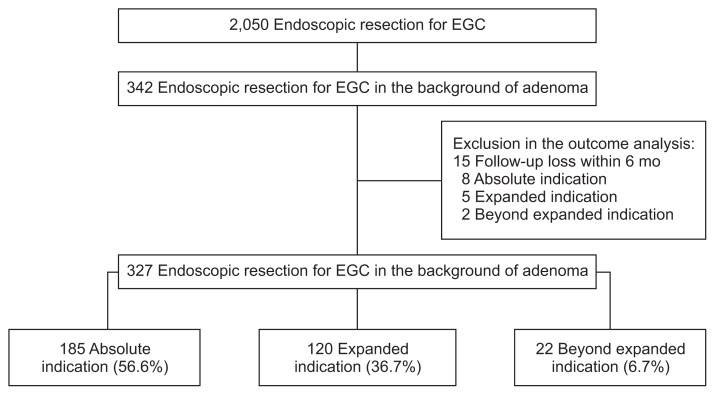

Between February 2011 and December 2014, 2,050 consecutive patients underwent ER for EGC at the Asan Medical Center, which is a tertiary academic center in Seoul, Korea. On reviewing the pathology report database, we found that 344 were diagnosed with gastric cancer arising from adenoma. After histological reanalysis, two patients were found to have de novo gastric cancer. We analyzed the medical records of the remaining 342 patients with gastric cancer arising from adenoma (Fig. 1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB number: 2016-0825). Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent. For full disclosure, the details of the study are published on the home page of Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patient enrollment. Median follow-up period was 24 months (interquartile range, 14.1 to 37).

EGC, early gastric cancer.

2. Evaluation of endoscopic features

Endoscopic reports and photographs of the procedures were reviewed using electronic medical records for each patient, assessing morphological type, ulceration, and location of the lesions. Lesions with active ulceration or accompanying fibrous scarring were reported as ulcerated. Tumor location was categorized based on the longitudinal axis of the stomach: upper third, containing the fundus, cardia, and upper body; middle third, containing the mid-body, lower body, and angle; and lower third, containing the antrum and pylorus.16 Macroscopic classification of tumors was as follows: type I (protruded), IIa (superficial elevated), IIb (flat), IIc (superficial depressed), and III (excavated).16,17

3. Endoscopic procedures

Endoscopic procedures followed at our institution have been previously described.18 Briefly, for EMR, after we checked the lesion, saline solution containing epinephrine (0.01 mg/mL) mixed with indigo carmine was injected into the submucosal layer with a 23-gauge needle. The raised lesion was removed using an SD-9U-1 or SD-12U-1 snare (Olympus Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) after circumferential mucosal incision. For ESD, the typical procedure involved marking, mucosal incision, and submucosal dissection with simultaneous hemostasis. After making several marking dots outside the lesion, saline solution containing epinephrine and indigo carmine was injected into the submucosal layer with a 23-gauge needle. A circumferential incision was made into the mucosa using a needle-knife (MTW Endoskopie Co., Ltd., Wesel, Germany) or insulated-tipped knife (Olympus Co., Ltd.). The submucosal layer was directly dissected with various knives until the lesion was completely removed. Hemostasis was achieved with hemoclips or hemostatic forceps (FD-410LR; Olympus Co., Ltd.) whenever bleeding or an exposed vessel was observed.

4. Histological analysis

The resected specimen was stretched, pinned to a polystyrene plate, and completely immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. After applying red, green, and yellow ink to the lateral resection margins and black ink to the deep resection margins, the entire specimen was sectioned into 2-mm thick slices parallel to an imaginary line drawn from the edge of the tumor to the closest resection margin (Fig. 2). Each sliced tissue specimen was embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were cut from each paraffin block and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Each slide was then examined to determine the extent of tumor involvement. The borders of the tumors were indicated on mapping paper (Fig. 2). The carcinoma component was analyzed by histological examination according to the area of the entire tumor tissue occupied by adenocarcinoma. All lesions were classified as gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia according to Vienna classification, i.e., low-grade adenoma/dysplasia as category 3, high-grade adenoma/dysplasia or noninvasive carcinoma as category 4, and intramucosal or submucosal carcinoma or beyond as category 5.19 The histological type of gastric cancer was classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.20 The degree of differentiation was classified as differentiated (well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma or papillary adenocarcinoma) or undifferentiated (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, or mucinous cell carcinoma). Patients with adenomatous components at the margin of the carcinoma were defined as cancers arising from adenomas. Lymphovascular invasion was defined as observable spread of tumor cells into the lymphatic vessels (e.g., carcinoma cells floating within the endothelia-lined space). In order to confirm the lymphovascular invasion, most cases were deciphered using the H&E stain. Only in case where it was unsure whether it is an artifact or true vessel, immunohistochemical CD34 stain or monoclonal antibody D2-40 were used. Depth of invasion was categorized as lamina propria, muscularis mucosa, or submucosa.16 Submucosal invasion was classified into three layers: SM1 (penetration of <500 μm into the submucosal layer from the muscularis mucosa), SM2 (penetration of 500 to 1,000 μm), and SM3 (penetration of ≥1,000 μm).

Fig. 2.

Example of calculation of estimated cancer size. (A) The gross whole tumor size, which was measured using a ruler based on the dimension of the endoscopically resected specimen, was 12 cm. (B) Mapping paper showed cancer in the red area and adenoma in the blue area. The microscopic whole tumor size, which was measured using the mapping paper, was 10.4 cm. The carcinoma component, which was analyzed by a histological examination according to the area occupied by cancer within the whole tumor tissue, was 20%. (C) Example of calculation of estimated cancer size in this case. The estimated cancer size was 4.65 cm, and the degree of differentiation was the differentiated type (well-differentiated adenocarcinoma). The depth of invasion was submucosa. Thus, this case was classified as beyond absolute indication.

5. Size measurement and calculation

Gross whole tumor size was measured using a ruler based on the dimensions of the endoscopically resected specimen. Microscopic whole tumor size was measured on mapping paper (Fig. 2).

Maximum diameter was used as the measure for tumor size. Estimated cancer size was calculated using the microscopic whole tumor size and square root of the carcinoma component.

Estimate the cancer size was calculated by following equation: microscopic whole tumor size (cm)×√carcinoma component (%)/100

6. Indications for ER

Estimated cancer size was the basis for determining whether ER was indicated. The absolute indications include differentiated elevated cancer of <2 cm in diameter and depressed cancer of <1 cm in diameter without ulceration.21 Expanded indications include differentiated mucosal cancer of >2 cm in diameter without ulceration, differentiated mucosal cancer of up to 3 cm in diameter with ulceration, undifferentiated mucosal cancer of up to 2 cm in diameter without ulceration, or a submucosal cancer not deeper than SM1 and <3 cm in diameter.22 ER was considered to have been performed beyond the expanded indications if any of the values for the expanded indications were exceeded.

7. Evaluation after ER

Curative resection was defined when all of the following conditions were met: final mapping results within the expanded indications, en bloc resection, negative horizontal and vertical margins, and absence of lymphatic invasion and venous involvement.13 Evaluation for lymph node (LN) metastasis was based on pathological results from surgery or surveillance computed tomography (CT), looking for perigastric LNs. Pathology was available if patients underwent additional gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy after ER; otherwise, patients were followed up with endoscopic examination and abdominal CT. Both were performed every 6 months for the first 2 years, and then annually for the next 3 years. Patients were excluded from outcome analysis if they were seen for less than 6 months of follow-up.

8. Statistical analysis

The chi-square or Fisher exact test was used to assess relationships among categorical variables and t-test was used for non-categorical variables. Factors associated with ER performed beyond the expanded indications were analyzed using logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the effect of variables. All tests of significance were two-tailed, and p<0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

1. Clinicopathological characteristics

A total of 342 patients (256 men; mean age, 64.6±9.5 years) were enrolled. The mean gross whole tumor size was 2.6±1.8 cm. The most predominant gastric location was the lower third (221/342, 64.6%). In resected specimens, mucosal layer invasion was confirmed in 313 cases (91.5%), SM1 invasion in 16 (4.7%), and SM2 invasion in 13 (3.8%). Most tumors were differentiated (336/342, 98.2%), with only six (1.8%) being undifferentiated (poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or signet ring cell carcinoma). The mean carcinoma component was 31.9%±27.1%, and the mean estimated cancer size was 1.3±1.0 cm. Indications for ER were considered to have been absolute in 193 cases (56.5%), expanded in 125 (36.5%), and beyond the expanded indications in 24 (7%). The baseline, pathological, and endoscopic characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline, Pathological, and Endoscopic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 64.6±9.5 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 256 (74.9) |

| Female | 86 (25.1) |

| Gross whole tumor size, cm | 2.6±1.8 |

| Location | |

| Upper third | 34 (9.9) |

| Middle third | 87 (25.4) |

| Lower third | 221 (64.6) |

| Endoscopic type | |

| I | 13 (3.8) |

| IIa | 161 (47.1) |

| IIb | 47 (13.7) |

| IIc | 120 (35.1) |

| III | 1 (0.3) |

| Gross ulceration | |

| Negative | 316 (92.4) |

| Positive | 26 (7.6) |

| Initial forceps biopsy result | |

| LGD | 126 (36.8) |

| HGD | 117 (34.2) |

| WD | 88 (25.7) |

| MD | 11 (3.2) |

| Invasion layer | |

| M2 | 257 (75.1) |

| M3 | 56 (16.4) |

| SM1 | 16 (4.7) |

| SM2 | 13 (3.8) |

| Differentiation | |

| WD | 301 (88.0) |

| MD | 35 (10.2) |

| PD/SRC | 6 (1.8) |

| LVI | |

| Negative | 336 (98.2) |

| Positive | 6 (1.8) |

| Microscopic whole tumor size, cm | 2.6±1.8 |

| Carcinoma component, % | 31.9±27.1 |

| Estimated cancer size, cm | 1.3±1.0 |

| Indication after endoscopic resection | |

| Absolute | 193 (56.5) |

| Expanded | 125 (36.5) |

| Beyond expanded | 24 (7.0) |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

LGD, low-grade dysplasia; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; WD, well differentiated; MD, moderately differentiated; M2, lamina propria; M3, muscularis mucosa; SM1, submucosal 1 layer; SM2, submucosal 2 layer; PD, poorly differentiated; SRC, signet ring cell; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

2. Outcomes of ER based on the type of indication for curative resection in gastric cancer

Fifteen patients were lost to follow up, leaving 327 available for the outcome analysis (Fig. 1). The median follow-up duration was 24 months (interquartile range, 14.1 to 37 months). The curative resection rate was 92.7% overall, 100% (185/185) for lesions meeting the absolute indications, 98.3% (118/120) for lesions meeting the expanded indications, and 0% (0/22) for lesions beyond the expanded indications. Immediate surgery was performed in 54.2% patients (13/24) who had a non-curative resection, including one of the two with expanded indications and 12 of the 22 with lesions beyond the expanded indications. The 11 patients who did not undergo surgery were carefully followed up. Surgery was not performed in those cases because of severe comorbid illness, patient reluctance, or physician opinion. LN metastasis was found in only one patient; the overall rate of LN metastasis was 0.3% (1/327); 0% (0/185) in the absolute group, 0% (0/118) in the expanded group, and 4.5% (1/22) in the beyond the expanded group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes of Endoscopic Resection According to Indications for Endoscopic Resection

| Absolute (n=185) | Expanded (n=120) | Beyond expanded (n=22) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curative resection | 185 (100) | 118 (98.3) | 0 |

| Non-curative resection | 0 | 2 (1.7) | 22 (100) |

| Management of non-curative lesion | |||

| Immediate surgery | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Follow-up with surveillance CT | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| LN metastasis | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.5) |

| LN metastasis (surgery group) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| LN metastasis on CT (non-surgery group) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Data are presented as number (%) or number.

CT, computed tomography; LN, lymph node.

3. Comparison analysis between indications for ER (absolute or expanded vs beyond the expanded indications) in patients diagnosed as adenomas based on forceps biopsy

A total of 243 patients were diagnosed as adenomas with pre-procedural forceps biopsy. Among them, 16 patients were diagnosed as having lesions beyond expanded indications after ER. Gross whole tumor size, microscopic whole tumor size, estimated cancer size and carcinoma component were significantly larger in lesions beyond the expanded indications; submucosal invasion and gross ulceration were also more frequent (Table 3). By univariate analysis submucosal invasion, carcinoma component of ≥35%, estimated cancer size of ≥1.5 cm were significantly associated with lesions that were beyond the expanded indications (Table 4). By multivariate analysis, the following variables were independently associated with lesions beyond the expanded indications: gross whole tumor size of ≥3 cm (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.3 to 14; p<0.05), and carcinoma component of ≥35% (OR, 8.1; 95% CI, 2.4 to 27.5; p<0.05). Presence of gross ulceration was marginally significant (OR, 4.2; 95% CI, 0.95 to 18.9; p=0.058) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Baseline, Pathological, and Endoscopic Characteristics According to Indications after Endoscopic Resection in Patients Diagnosed with Adenomas Based on Forceps Biopsy

| Clinicopathological feature | Absolute or expanded indications (n=227) | Beyond expanded indications (n=16) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 65.1±9.1 | 66.0±8.6 | 0.71 |

| Sex | 0.25 | ||

| Male | 170 (74.9) | 14 (87.5) | |

| Female | 57 (25.1) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Location | 0.41 | ||

| Upper third | 26 (11.5) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Middle third | 58 (25.6) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Lower third | 143 (63.0) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Endoscopic type | 0.51 | ||

| I | 8 (3.5) | 2 (12.5) | |

| IIa | 115 (50.7) | 8 (50) | |

| IIb | 29 (12.8) | 2 (12.5) | |

| IIc | 74 (32.6) | 4 (25) | |

| III | 1 (0.4) | 0 | |

| Gross ulceration | 0.05 | ||

| Negative | 213 (93.8) | 13 (81.3) | |

| Positive | 14 (6.2) | 3 (18.8) |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses of Clinicopathological Parameters Associated with Lesions Other Than the Expanded Indications in Patients Diagnosed with Adenomas Based on Forceps Biopsy

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Gross whole tumor size, cm | ||||

| <3 (n=147) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥3 (n=96) | 2.7 (0.9–7.7) | 0.06 | 4.4 (1.3–14) | <0.05 |

| Initial forceps biopsy result | ||||

| LGD (n=126) | 1 | |||

| HGD (n=117) | 1.1 (0.3–2.9) | 0.87 | ||

| Invasion layer | ||||

| Mucosa (n=221) | 1 | |||

| SM (n=22) | 104.9 (25.3–434.8) | <0.05 | ||

| Carcinoma component, % | ||||

| <35 (n=159) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥35 (n=84) | 6.4 (2–20.7) | <0.05 | 8.1 (2.4–27.5) | <0.05 |

| Estimated cancer size, cm | ||||

| <1.5 (n=172) | 1 | |||

| ≥1.5 (n=71) | 6.1 (2–18.3) | <0.05 | ||

| Gross ulceration | ||||

| Negative (n=226) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Positive (n=17) | 3.5 (0.8–13.7) | 0.07 | 4.2 (0.9–18.9) | 0.058 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LGD, low-grade dysplasia; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; SM, submucosa.

DISCUSSION

Small de novo colorectal cancer, defined as tumors that have no demonstrable in situ (adenomatous) component, are reportedly more aggressive than conventional adenocarcinomas that develop from well-defined adenomatous precursor lesions.23–25 Analogously, gastric carcinoma arising from adenoma may be biologically different from de novo gastric cancer. However, to the best of our knowledge, clinical and biological features of gastric cancer arising from adenoma have rarely been reported. We conducted this study to evaluate whether the current criteria for curative resection of gastric cancer can be applied to gastric cancer arising from adenoma and to identify factors that can predict which lesions are beyond the expanded indications for ER. Previously reported rates of LN metastasis in cases where ER was performed beyond the expanded indications are as follows: (1) 3.0% (7/230) for >3 cm, predominantly differentiated, pT1a, and ulcerated lesions; (2) 2.6% (2/78) for >3 cm, predominantly differentiated, and pT1b (SM1) lesions; (3) 2.8% (6/214) for >2 cm, predominantly undifferentiated, pT1a, and non-ulcerated lesions; (4) 5.1% (52/1014) for predominantly undifferentiated, pT1a, and ulcerated lesions; and (5) 10.6% (9/85) for predominantly undifferentiated and pT1b (SM1) lesions.13,14,26 In this study, patients with gastric cancer arising from adenoma and considered suitable for ER by the absolute and expanded indications were believed to have a negligible risk of LN metastasis, and in fact, none of them did (Table 2). The LN metastasis rate of 4.5% in patients with lesions beyond the expanded indications was similar to that reported in previously published data.14,26 Therefore, our results suggest that the current indications for curative resection of gastric cancer can also be applied to gastric cancer arising from adenoma.

Non-curative ER because of errors in preoperative diagnosis is an inevitable consequence of the fact that evaluations based on endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), and even diagnostic biopsies before the procedure are not always accurate.27,28

The discrepancy rates between forceps biopsy samples and post-resected specimens ranged from 20% to 40% in previous reports.29–32 Discrepancies occur because the amount of tissue obtained by forceps biopsy is too small to represent the histology of the entire tumor lesions.33 In this study, endoscopies and forceps biopsies were performed on a total of 233 patients (68.1%) at the Asan Medical Center prior to the ER. Since results of endoscopies conducted at other hospitals were missing, the numbers of forceps biopsies of 41 patients were unknown. Analyzing the remaining 301 patients, the mean frequencies of forceps biopsy in concordance group were 3 and the mean frequencies of forceps biopsy in discrepancy group were 2.7. But the frequencies of forceps biopsy between two groups did not show significant difference.

Mandai and Yasuda34 measured the invasion depth of EGC using EUS. Among the 280 cases considered to have mucosal/SM1 cancer based on EUS findings, 20 (7.1%) had SM2 cancer. Of the tumors thought to be differentiated adenocarcinoma, 1.5% to 8.0% turn out to be undifferentiated after ESD.35,36 Histological discrepancy between pre- and post-ESD specimens can be attributed to inter- and intraobserver variability as well as to the fact that gastric cancer can have histological heterogeneity (containing both differentiated and undifferentiated areas).37,38 For these reasons, ESD has been recommended as a diagnostic tool for gastric lesions in cases where there is a discrepancy between the forceps biopsy pathology and endoscopic findings.39

Despite the diagnostic effectiveness and safety of ESD, there is a low incidence of adverse events with endoscopic procedures. A multicenter study40 showed that the incidences of post-ESD bleeding, perforation and serious adverse event were 5.5%, 4.7%, and 0.43%, respectively. Longer procedure times have been associated with an increased risk of adverse events,41,42 and tumor location and size may affect ESD procedure time.43–45 Although determining if the indications for curative ER have been met is difficult, accurate preoperative prediction of which EGC is beyond the expanded indications is very important to reduce the risks associated with an unnecessary procedure. Yamada et al.46 described three risk factors for submucosal and lymphovascular invasion in ESD specimens of EGC: a dominant histology of moderately differentiated or papillary adenocarcinoma, non-flat gross morphology, and tumor size of ≥1.5 cm. In another study, SM2 invasion was correlated on multivariate analysis with tumor size, ulceration, undifferentiated histology, gross type, and tumor location.47 We found several factors predictive of gastric carcinoma arising from adenoma being beyond the expanded indications for ER.

Gross whole tumor size of ≥3 cm (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.3 to 14; p<0.05) and carcinoma component of ≥35% (OR, 8.1; 95% CI, 2.4 to 27.5; p<0.05) were independently associated with lesions that were beyond the expanded indications and gross ulceration (OR, 4.2; 95% CI, 0.95 to 18.9; p=0.058) showed marginally significant association. Therefore, in cases suspicious of being beyond the expanded indications, very careful selection of the patients for ER is needed to reduce the risk associated with an unnecessary procedure.

There are several limitations to our study. First, this was a single-center retrospective study. Second, we defined the absence of LN metastasis radiologically in most patients, as pathology was unavailable for those not undergoing surgery. Considering the approximately 90% negative predictive value of stomach protocol CT,48 it is possible that some patients with normal CT findings at 12 months of follow-up had LN metastasis that went undetected. Third, the carcinoma component is not a pre-procedure clinicopathological parameter. The endoscopic features suggesting the presence of carcinomatous foci in gastric adenoma, as reported by Kasuga et al.49 include a lesion size of >20 mm and central-depressed appearance. Further, Ko et al.33 reported that surface redness seen on endoscopy suggested an underestimation on forceps biopsy. Although the carcinoma component is a post-procedure parameter, the aforementioned endoscopic findings suggest the presence of a carcinomatous component in gastric adenoma. For validation that such findings are predictive of carcinoma component before ER, further study is needed on the endoscopic appearance compared with subsequent findings on pathology (Fig. 2). Fourth, the calculation method to estimate the cancer size suggested in this research is under the hypothesis that the tumor is round. If it is hypothesized that the shape of the adenoma is oval, then the estimated cancer size using the calculation method suggested in this study overestimate the cancer size. However, most cancers are distributed in a mosaic pattern thus it is impossible to calculate the exact extent, as shown in the case (Fig. 2). Therefore, the size discrepancy can be considered as a limitation of this study.

Despite these limitations, our study is the first regarding EGC arising from adenoma. Our results suggest several clinicopathological characteristics predicting that the lesion is beyond the expanded indications for ER. The rate of standardized follow-up in our series was high (95.6%, 327/342), and the endoscopic procedures and pathology examinations were performed according to a standard protocol.

In this study, the LN metastasis rate was 0% (0/185) in the absolute indications, 0% (0/118) in the expanded indications, and 4.5% (1/22) in beyond the expanded indications. Therefore, the current indications for curative ER of gastric cancer can be applied to gastric cancer arising from adenoma. Gross whole tumor size of ≥3 cm and carcinoma component of ≥35% were independently associated with lesions that were beyond the expanded indications and gross ulceration showed marginally significant association. Accordingly, in cases with these clinicopathological parameters, cautious selection of patients for ER is needed to reduce the risk of an inappropriate procedure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Author contributions: K.D.C. designed and supervised the research; S.H.P. and K.D.C. reviewed medical records and analyzed the data; S.H.P. and Y.P. reviewed pathology; S.H.P., K.J., S.L., E.J.G., H.K.N. collected data; S.H.P., J.Y.A., K.W.J., J.H.L., D.H.K., H.J.S., G.H.L. interpreted data; H.Y.J. reviewed and supervised study concept.

Footnotes

See editorial on page 219.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Gastric adenomas: intestinal-type and gastric-type adenomas differ in the risk of adenocarcinoma and presence of background mucosal pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1276–1285. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamada H, Ikegami M, Shimoda T, Takagi N, Maruyama M. Long-term follow-up study of gastric adenoma/dysplasia. Endoscopy. 2004;36:390–396. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rugge M, Cassaro M, Di Mario F, et al. The long term outcome of gastric non-invasive neoplasia. Gut. 2003;52:1111–1116. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.8.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rugge M, Farinati F, Baffa R, et al. Gastric epithelial dysplasia in the natural history of gastric cancer: a multicenter prospective follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho SJ, Choi IJ, Kim CG, et al. Risk of high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in gastric biopsy-proven low-grade dysplasia: an analysis using the Vienna classification. Endoscopy. 2011;43:465–471. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MK, Jang JY, Kim JW, et al. Is lesion size an independent indication for endoscopic resection of biopsy-proven low-grade gastric dysplasia? Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:428–435. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim H, Jung HY, Park YS, et al. Discrepancy between endoscopic forceps biopsy and endoscopic resection in gastric epithelial neoplasia. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1256–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim CG. Tissue acquisition in gastric epithelial tumor prior to endoscopic resection. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:436–440. doi: 10.5946/ce.2013.46.5.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi CW, Kim HW, Shin DH, et al. The risk factors for discrepancy after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric category 3 lesion (low grade dysplasia) Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:421–427. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2874-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isomoto H, Shikuwa S, Yamaguchi N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large-scale feasibility study. Gut. 2009;58:331–336. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.165381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung IK, Lee JH, Lee SH, et al. Therapeutic outcomes in 1000 cases of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: Korean ESD Study Group multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1228–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oka S, Tanaka S, Kaneko I, et al. Advantage of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with EMR for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–225. doi: 10.1007/PL00011720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gotoda T, Iwasaki M, Kusano C, Seewald S, Oda I. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer treated by guideline and expanded National Cancer Centre criteria. Br J Surg. 2010;97:868–871. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/PL00011681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endoscopic Classification Review Group. Update on the Paris classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the digestive tract. Endoscopy. 2005;37:570–578. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn JY, Jung HY, Choi KD, et al. Endoscopic and oncologic outcomes after endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: 1370 cases of absolute and extended indications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, et al. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251–255. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jass JR, Sobin LH, Watanabe H. The World Health Organization’s histologic classification of gastrointestinal tumors: a commentary on the second edition. Cancer. 1990;66:2162–2167. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901115)66:10<2162::AID-CNCR2820661020>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tada M, Murakami A, Karita M, Yanai H, Okita K. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 1993;25:445–450. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4490–4498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.19.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuramoto S, Oohara T. Flat early cancers of the large intestine. Cancer. 1989;64:950–955. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890815)64:4<950::AID-CNCR2820640430>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimoda T, Ikegami M, Fujisaki J, Matsui T, Aizawa S, Ishikawa E. Early colorectal carcinoma with special reference to its development de novo. Cancer. 1989;64:1138–1146. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890901)64:5<1138::AID-CNCR2820640529>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stolte M, Bethke B. Colorectal mini-de novo carcinoma: a reality in Germany too. Endoscopy. 1995;27:286–290. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:148–152. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0515-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and conventional endoscopy for prediction of depth of tumor invasion in early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2010;42:705–713. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi J, Kim SG, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Is endoscopic ultrasonography indispensable in patients with early gastric cancer prior to endoscopic resection? Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3177–3185. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim HW, Park SB, Kim S, Cho M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection as a treatment for gastric adenomatous polyps: predictive factors for early gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1218–1225. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.666674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szalóki T, Tóth V, Tiszlavicz L, Czakó L. Flat gastric polyps: results of forceps biopsy, endoscopic mucosal resection, and long-term follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1105–1109. doi: 10.1080/00365520600615880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung HY, Cheung DY, Cho SH, et al. Polyps in the gastrointestinal tract: discrepancy between endoscopic forceps biopsies and resected specimens. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:190–195. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283140ebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon WJ, Lee DH, Jung YJ, et al. Histologic characteristics of gastric polyps in Korea: emphasis on discrepancy between endoscopic forceps biopsy and endoscopic mucosal resection specimen. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4029–4032. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ko SJ, Yang MA, Yun SH, Park MS, Han SH, Cho JW. Predictive factors suggesting an underestimation of gastric lesions initially diagnosed as adenomas by forceps biopsy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2016;27:115–121. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2016.160311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandai K, Yasuda K. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography for determining the treatment method for early gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:245390. doi: 10.1155/2012/245390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takao M, Kakushima N, Takizawa K, et al. Discrepancies in histologic diagnoses of early gastric cancer between biopsy and endoscopic mucosal resection specimens. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:91–96. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CK, Chung IK, Lee SH, et al. Is endoscopic forceps biopsy enough for a definitive diagnosis of gastric epithelial neoplasia? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1507–1513. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.006367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haruma K, Sumii K, Inoue K, Teshima H, Kajiyama G. Endoscopic therapy in patients with inoperable early gastric cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:522–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luinetti O, Fiocca R, Villani L, Alberizzi P, Ranzani GN, Solcia E. Genetic pattern, histological structure, and cellular phenotype in early and advanced gastric cancers: evidence for structure-related genetic subsets and for loss of glandular structure during progression of some tumors. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:702–709. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(98)90279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee H, Kim H, Shin SK, et al. The diagnostic role of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric lesions with indefinite pathology. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1101–1107. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2012.704939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato M, Nishida T, Tsutsui S, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection as a treatment for gastric noninvasive neoplasia: a multi-center study by Osaka University ESD Study Group. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:325–331. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee IL, Wu CS, Tung SY, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers: experience from a new endoscopic center in Taiwan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:42–47. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225696.54498.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isomoto H, Ohnita K, Yamaguchi N, Fukuda E, Ikeda K, Nishiyama H, et al. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection in elderly patients with early gastric cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:311–317. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832c61d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kakushima N, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Muraki Y, Tateishi A, Omata M. A learning curve for endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric epithelial neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2006;38:991–995. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goto O, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Ono S, Omata M. Is it possible to predict the procedural time of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:379–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahn JY, Choi KD, Choi JY, et al. Procedure time of endoscopic submucosal dissection according to the size and location of early gastric cancers: analysis of 916 dissections performed by 4 experts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:911–916. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamada T, Sugiyama H, Ochi D, et al. Risk factors for submucosal and lymphovascular invasion in gastric cancer looking indicative for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:692–696. doi: 10.1007/s10120-013-0323-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim JM, Sohn JH, Cho MY, et al. Pre- and post-ESD discrepancies in clinicopathologic criteria in early gastric cancer: the NECA-Korea ESD for Early Gastric Cancer Prospective Study (N-Keep) Gastric Cancer. 2016;19:1104–1113. doi: 10.1007/s10120-015-0570-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MW, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of T and N stages with endoscopy, stomach protocol CT, and endoscopic ultrasonography in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:20–27. doi: 10.1002/jso.21170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kasuga A, Yamamoto Y, Fujisaki J, et al. Clinical characterization of gastric lesions initially diagnosed as low-grade adenomas on forceps biopsy. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:331–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]