Abstract

Background/Aims

Rebleeding is associated with mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB), and risk stratification is important for the management of these patients. The purpose of our study was to examine the risk factors associated with rebleeding in patients with PUB.

Methods

The Korean Peptic Ulcer Bleeding registry is a large prospectively collected database of patients with PUB who were hospitalized between 2014 and 2015 at 28 medical centers in Korea. We examined the basic characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients in this registry. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify the factors associated with rebleeding.

Results

In total, 904 patients with PUB were registered, and 897 patients were analyzed. Rebleeding occurred in 7.1% of the patients (64), and the 30-day mortality was 1.0% (nine patients). According to the multivariate analysis, the risk factors for rebleeding were the presence of co-morbidities, use of multiple drugs, albumin levels, and hematemesis/hematochezia as initial presentations.

Conclusions

The presence of co-morbidities, use of multiple drugs, albumin levels, and initial presentations with hematemesis/hematochezia can be indicators of rebleeding in patients with PUB. The wide use of proton pump inhibitors and prompt endoscopic interventions may explain the low incidence of rebleeding and low mortality rates in Korea.

Keywords: Peptic ulcer hemorrhage, Rebleeding, Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) is a common medical emergency and cause of hospital admission.1 Peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB) accounts for the majority of NVUGIB and is a major cause of mortality, morbidity, and health care expenditure.2 Despite advances in medications and therapeutic techniques, the rebleeding and mortality rates remain unchanged at 5% to 8% over the past 30 years.3–5 Re-bleeding has been reported to be a major factor associated with mortality in PUB and often prevents early discharge from hospitals.6,7 Therefore, prediction of rebleeding is important in determining whether a patient needs close monitoring or admission to the intensive care unit. Second look endoscopy performed for high-risk patients and early discharge of selected low-risk patients may be cost effective in this regard.8,9 A number of risk factors have been proposed as predictors of recurrent bleeding after upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and several risk models have been developed to aid in initial decision making.10–13 However, these studies included a mixed population of acute UGIB. Few studies have focused on rebleeding as an adverse outcome after PUB.13–15 Also, most of these studies were performed before the broad use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and before the development or wide spread use of current endoscopic hemostatic instruments. Few have reported the risk factors of rebleeding with regard to the recent changes in medical therapy such as PPIs and new endoscopic hemostatic therapies. New data regarding risk factors of rebleeding and risk stratification based on recent international guidelines are warranted.14 The main aim of this study was to examine the factors associated with rebleeding for PUB in the current era of PPI use and endoscopic hemostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. The K-PUB initiative and data collection

This was a prospective cohort study and 28 centers across Korea participated in the Korean Registry on Peptic Ulcer Bleeding (K-PUB) study group. Specially trained research assistants registered the patients immediately after endoscopic examination on web-based system. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each hospital and was registered at Clinicaltrial.gov. (NCT02152904). All patients gave written informed consent to participate in our study before the endoscopy.

2. Patient population

All patients that presented with overt UGIB were considered for enrollment. Patients with a history of hematemesis/coffee ground vomiting, melena, hematochezia, or a combination of any of the above received endoscopy. If endoscopic findings revealed peptic ulcers the patients were eligible for enrollment. Patients in whom the source of bleeding was other than PUB were excluded (varices, hemorrhagic erosive gastritis, Mallory-Weiss tears, Dieulafoy’s lesions, vascular ectasia, and malignancies). When the lesion was turned out to be malignant after histopathologic review, the data was discarded.

3. Study variables

Recorded information included the following independent variables: demographic information (age, sex, alcohol, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, comorbidities, and medication), physical examinations (height, weight, blood pressure, pulse rate), American Society of Anesthesiologists classification,15 initial laboratory data (complete blood count, blood urea nitrogen [BUN], creatinine, albumin), endoscopic components (time to endoscopy, experience of endoscopists, Forrest classification, method and results of endoscopic hemostasis), pharmacologic therapy, and performance of other therapies (surgery, angiography). Presence of Helicobacter pylori infection was determined by histologic examination or rapid urease test from biopsies taken during the examination. Comorbidity was defined as follows: cardiovascular disease included cardiac arrhythmia, ischemic heart disease, and chronic heart failure. Pulmonary disease included both chronic (e.g., bronchitis or chronic obstructive lung disease) and acute (e.g., pneumonia) conditions. Kidney failure included both mild forms (e.g., abnormal serum creatinine value) and severe forms (e.g., need for dialysis). Liver failure included both mild forms (e.g., having an abnormal serum bilirubin value) and severe forms (e.g., end-stage liver failure). Previous diagnoses of malignancies were also included. Medications were defined as antiplatelets (including aspirin), anticoagulants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and steroids. Patients who took more than one of the aforementioned medication were classified as multidrug. Information of patients who used one of these drugs within 1 week of ulcer bleeding was recorded. Endoscopy performed between 12:00 AM Monday and 11:59 PM Friday were classified as weekdays. Time to endoscopy was calculated from presentation to emergency room or the first documentation of bleeding if it occurred in an inpatient.

4. Endoscopic evaluation

An ulcer was defined as a lesion with loss of mucosal integrity and continuity of ≥5 mm. Bleeding activity was classified according to the modified Forrest classification.16 Endoscopic hemostasis was performed at the discretion of the endoscopist and included thermal coagulation, hemoclipping, and epinephrine injection. In case of more than one ulcer, the ulcer with the most severe Forrest classification was used in the classification and analysis.

5. Outcomes

The outcomes included the frequency of rebleeding, surgical therapy or angiography, and mortality. The primary outcome of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with rebleeding within 30 days after initial hemostasis. Rebleeding was defined as recurrent hematemesis, coffee ground vomiting, melena, hematochezia, and a drop in hemoglobin of 2 g/dL after the initial hemostasis. The secondary outcome was to evaluate the need for radiographic intervention or surgery and the in-hospital mortality rates were also examined.

6. Data analysis

All the dependent variables were presented as descriptive data. All continuous data were expressed as means±standard deviation. The statistical difference of baseline characteristics between rebleeding and non-rebleeding groups were assessed using the Student t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Univariate analysis was performed to assess risk factors related to rebleeding. Multivariate analysis using a selection of variables significant at the 0.10 level by univariate analysis was applied to assess independent risk factors associated with rebleeding.

RESULTS

1. Study population

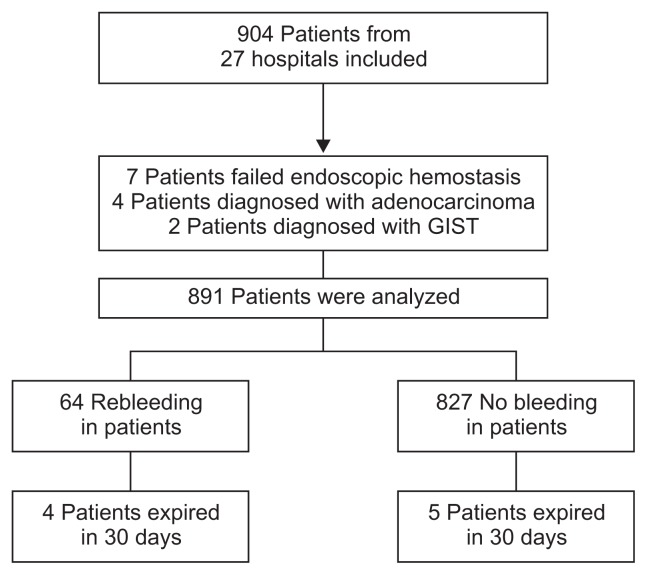

Between May 2014 and March 2015, 904 patients from 28 centers all over the country with PUB were registered in the K-PUB data base and 891 patients were analyzed (Fig. 1). Descriptive data are presented in Table 1. Median age was 63 years and 76% were males. Antiplatelets (including aspirin) were the most common medications used followed by NSAIDs, anticoagulants, and steroids. Intravenous PPIs were used in 96% of patients. The average time to endoscopy was 14 hours. Second look endoscopy was performed in 71% of patients. H. pylori infection status was examined in 798 patients and 302 were positive for H. pylori infection (37.8%). Rebleeding occurred in 7.1% (64 patients) and 30 day mortality was 1.0% (nine patients). Two patients expired due to bleeding related complications and the remaining patients expired due to their underlying comorbidities.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patients included in this study.

GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Table 1.

Baseline and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients (n=891)

| Measure | Value |

|---|---|

| Male sex | 679 (76.2) |

| Age, yr | 63±15 |

| Alcohol | 386 (43.3) |

| Smoking | 309 (34.7) |

| Hypertension* | 434 (49.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 211 (23.8) |

| Comorbidity* | 415 (46.8) |

| Drugs* | |

| Anti-platelets | 297 (33.4) |

| Anticoagulants | 51 (5.7) |

| NSAIDs | 117 (13.1) |

| Steroids | 19 (2.1) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.9±3.4 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 116±22 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 70±15 |

| Pulse rates, /min | 93±21 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.2±5.0 |

| White blood cell, /mm3 | 11,396±7,042 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 42.3±37.0 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.3±0.6 |

| Mental status (alert) | 871 (97.8) |

| Endoscopy (weekdays) | 598 (67.1) |

| Experience (≥3 yr) | 315 (35.4) |

Data are presented as the number (%) or mean±SD.

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

The data were missing for certain patients.

2. Endoscopic findings and treatment

Table 2 shows endoscopic findings and clinical outcomes. Five patients who failed to achieve initial endoscopic hemostasis received radiographic interventions and two patients received surgery. Gastric ulcers were more common than duodenal ulcers (60.9% vs 29.9%). Sixty-nine patients had active arterial bleeding, 224 had oozing, 290 had nonbleeding visible vessel, 141 had adherent clots, 146 had flat hematins, and 21 had clean ulcers. A total of 675 patients (75.8%) were treated endoscopically. Three hundred seventy-seven patients among 675 patients (42.3%) received combination endoscopic hemostasis (e.g., epinephrine injection plus thermal coagulation or hemoclipping, thermal coagulation plus hemoclipping). The remaining 298 patients (33.4%) received single therapy (epinephrine injection, hemoclip, band ligation, and thermocoagulation).

Table 2.

Endoscopic Findings and Clinical Outcomes of 891 Study Patients

| Measure | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Gastric | 543 (60.9) |

| Duodenum | 264 (29.9) |

| Both | 84 (9.4) |

| Forrest classification | |

| Ia | 69 (7.7) |

| Ib | 224 (25.1) |

| IIa | 290 (32.5) |

| IIb | 141 (15.8) |

| IIc | 146 (16.4) |

| III | 21 (2.4) |

| Endoscopic hemostasis | 675 (75.8) |

| Monotherapy | 298 (33.4) |

| Combined therapy | 377 (42.3) |

| Second look endoscopy | 616 (71.0) |

| 30 Day-rebleeding rate | 64 (7.2) |

| 30 Day-mortality rate | 9 (1.0) |

| Transfusion | 568 (63.7) |

| Transfusion units* | 3.2±2.4 |

Mean±SD.

3. Comparison of baseline characteristics between groups

There were no significant differences between rebleeding and non-rebleeding groups in male to female ratio, Forrest classification, time to endoscopy, and rate of H. pylori infection (Table 3). Patients in the rebleeding group were older (67.8±14.4 vs 62.2±15.2, p=0.005), more frequent users of NSAIDs (25.8% vs 12.2%, p=0.002), and multidrugs (25.8% vs 7.6%, p=0.000). Albumin levels were lower in the rebleeding group (3.0 vs 3.3, p=0.000). Patients presented with hematemesis/hematochezia (53.2 vs 34.7, p=0.003) and required transfusion more often in the rebleeding group (77.4% vs 62.7%, p=0.020).

Table 3.

Comparison of Patients with and without Rebleeding

| Measure | No rebleeding (n=829) | Rebleeding (n=62) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 633 (76.4) | 46 (74.2) | 0.700 |

| Age, yr | 62.2±15.2 | 67.8±14.4 | 0.005 |

| Alcohol | 361 (43.5) | 25 (40.3) | 0.621 |

| Smoking | 289 (34.9) | 20 (32.3) | 0.678 |

| Hypertension* | 401 (48.7) | 33 (53.2) | 0.488 |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 197 (23.9) | 14 (22.6) | 0.813 |

| Comorbidity* | 384 (46.6) | 31 (50.0) | 0.437 |

| Antiplatelets* | 271 (32.7) | 26 (41.9) | 0.138 |

| Anticoagulants* | 46 (5.6) | 5 (8.1) | 0.412 |

| NSAIDs* | 101 (12.2) | 16 (25.8) | 0.002 |

| Steroids* | 15 (1.8) | 4 (6.5) | 0.037 |

| Multidrug | 63 (7.6) | 16 (25.8) | 0.000 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.0±3.4 | 22.2±3.3 | 0.071 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 116±22 | 113±25 | 0.431 |

| Pulse rate, /min | 93±22 | 92±17 | 0.653 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.2±5.1 | 8.9±2.7 | 0.672 |

| White blood cell, /mm3 | 11,432±7,174 | 11,327±5,610 | 0.910 |

| Platelet, /mm3 | 236,125±98,510 | 238,280±78,532 | 0.866 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 42.2±37.7 | 49.1±52.0 | 0.177 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.5±5.0 | 1.4±1.2 | 0.872 |

| INR | 1.4±3.0 | 1.2±0.4 | 0.614 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.3±0.6 | 3.0±0.6 | 0.000 |

| Time to endoscopy | 14±5 | 14±5 | 0.409 |

| Mental status (alert) | 810 (97.7) | 61 (98.4) | 0.589 |

| ASA (I) | 273 (32.9) | 15 (24.2) | 0.174 |

| Hematemesis/hematochezia* | 286 (34.7) | 33 (53.2) | 0.003 |

| Endoscopy (weekdays) | 552 (66.6) | 46 (74.2) | 0.174 |

| Experience (≥3 yr) | 292 (35.2) | 23 (37.1) | 0.766 |

| Forrest classification | 0.205 | ||

| Ia | 62 (7.5) | 7 (11.3) | |

| Ib | 202 (24.4) | 22 (35.5) | |

| IIa | 275 (33.2) | 15 (24.2) | |

| IIb | 132 (15.9) | 9 (14.5) | |

| IIc | 139 (16.8) | 7 (11.3) | |

| III | 19 (2.3) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Forrest classification high risk group (Ia, Ib, IIa) | 539 (65.0) | 44 (71.0) | 0.342 |

| Monotherapy | 278 (45.4) | 20 (43.5) | 0.806 |

| Transfusion | 520 (62.7) | 48 (77.4) | 0.020 |

| Transfusion units | 3±2 | 6±4 | 0.000 |

| Second look endoscopy* | 563 (69.9) | 53 (85.5) | 0.090 |

| Helicobacter pylori infection† | 279 (37.5) | 23 (42.6) | 0.120 |

Data are presented as number (%) or mean±SD.

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; INR, international normalized ratio; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology.

The data were missing for certain patients;

H. pylori infection was not examined in 93 patients.

4. Predictive factors for 30-day rebleeding

Table 4 shows the univariate and multivariate analysis for factors affecting the risk of rebleeding. In univariate analysis, age, use of NSAIDs, steroids, multidrugs, body mass index, albumin, and hematemesis/hematochezia were significantly associated with rebleeding. In multivariate analysis, presence of co-morbidities (odds ratio [OR], 2.947; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.298 to 6.691; p=0.010), the use of multidrugs (OR, 3.105; 95% CI, 1.181 to 8.165; p=0.022), albumin level (OR, 0.508; 95% CI, 0.305 to 0.846; p=0.009), and hematemesis/hematochezia (OR, 1.882; 95% CI, 1.008 to 3.256; p=0.024) were independently associated with rebleeding.

Table 4.

Predictive Factors Associated with Rebleeding According to Univariate and Multivariate Regression Analyses

| Measure | Univariate OR (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 1.123 (0.622–2.028) | 0.700 | ||

| Age | 1.027 (1.008–1.046) | 0.005 | ||

| Comorbidity | 1.229 (0.661–2.286) | 0.514 | 2.947 (1.298–6.691) | 0.010 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 0.995 (0.984–1.007) | 0.430 | ||

| Pulse rate | 0.997 (0.984–1.010) | 0.651 | ||

| Antiplatelet | 1.766 (0.670–4.653) | 0.250 | ||

| Anticoagulant | 1.491 (0.570–3.900) | 0.415 | ||

| NSAIDs | 2.504 (1.366–4.588) | 0.003 | ||

| Steroids | 3.738 (1.202–11.625) | 0.023 | ||

| Multidrug | 4.224 (2.263–7.884) | 0.000 | 3.105 (1.181–8.165) | 0.022 |

| Body mass index | 0.929 (0.858–1.006) | 0.070 | ||

| Hemoglobin | 0.981 (0.903–1.067) | 0.659 | ||

| White blood cell | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.910 | ||

| Platelet | 1.000 (1.000–1.000) | 0.866 | ||

| Blood urea nitrogen | 1.003 (0.998–1.007) | 0.218 | ||

| Creatinine | 0.994 (0.928–1.065) | 0.873 | ||

| Albumin | 0.404 (0.262–0.622) | 0.000 | 0.508 (0.305–0.846) | 0.009 |

| Experience (≥3 yr) | 1.085 (0.635–1.851) | 0.766 | ||

| Weekends | 1.238 (0.706–2.172) | 0.456 | ||

| Time to endoscopy | 0.976 (0.923–1.033) | 0.409 | ||

| Hematemesis/hematochezia | 2.145 (1.276–3.604) | 0.004 | 1.882 (1.008–3.256) | 0.024 |

| Forrest classification high risk group | 1.315 (0.746–2.318) | 0.343 | ||

| Monotherapy | 0.927 (0.507–1.696) | 0.806 | ||

| Transfusion | 2.037 (1.105–3.756) | 0.023 | ||

| Second look endoscopy | 0.710 (0.299–1.689) | 0.439 | ||

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 0.528 (0.278–1.003) | 0.051 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

DISCUSSION

Rebleeding in PUB patients have been reported to be associated with increased mortality and hospital admission. Old age, shock, poor overall health status, comorbid illness, and low initial hemoglobin levels have been reported to be associated with rebleeding.17 A meta-analysis reported high serum C-reactive protein levels, hemodynamic instability and low hemoglobin levels as risk factors of rebleeding for peptic ulcers.18 However, most of the studies included in this analysis were performed in pre-PPI era and endoscopic treatment was very limited. The strength of this study is nationwide study recruiting patients from 28 centers in Korea in a short period, less than a year.

In this study, we described factors that were independently associated with rebleeding in a prospective cohort of 897 patients with PUB. Current guidelines recommend that risk stratification based on prognostic scores for patients presenting with NVUGIB.19 However, these scoring systems are difficult to calculate and a recent survey revealed that only 30% of physicians used these scoring systems for evaluation of a patient with NVUGIB.20 In our study, presence of comorbidities, use of multidrugs, albumin levels, and initial presentation of hematemesis/hematochezia were identified as indicators of rebleeding in PUB patients. Present risk assessment tools do not take account of patients taking drugs and our results indicate that this may be important in risk assessment.

A recent study reported that an increasing BUN at 24 hours to be a predictor of worse outcomes in patients with NVUGIB.21 The authors hypothesized under-resuscitation leading to prerenal azotemia as the reason for the association of a rising BUN and worse clinical outcomes. We were not able to measure the change in BUN 24 hours after presentation but BUN levels tended to be higher in the rebleeding group. Collectively, these findings emphasize the importance of fluid resuscitation in patients presenting with NVUGIB.

A rebleeding rate of 7.1% in our study was significantly lower than those reported in previous studies. A Canadian registry reported rebleeding, surgery, and mortality rates of 14.1%, 6.5%, and 5.4%, respectively.4 In that study, intravenous PPI therapy was used in 56% of the patients and repeated endoscopy was performed in 25% of the patients. In contrast, intravenous PPIs were used for 96% of patients and the vast majority of patients received second-look endoscopy in our study. Although, routine second-look endoscopy is not recommended for the management of PUB, it may be effective in patients at high risk of recurrent bleeding.22 Mortality occurred in nine patients (1%) and is lower than previous mortality rates related to bleeding ulcers of 7.4% to 11%.23–25 However, our results are in concordance with a recent study that reported mortality rates of 0.7%.26 Endoscopic hemostasis, and PPI use have been shown to reduce recurrent bleeding and mortality after NVUGIB. High-dose PPI therapy has been demonstrated to significantly reduce rebleeding in patients with high-risk stigmata following endoscopic therapy.27–29 The low rebleeding and mortality rates in our study may be attributed to these factors.

There are some limitations to our study. Factors that may be associated with rebleeding such as ulcer size and location were not investigated in our study. Written informed consent was obligatory for enrollment and patients who were critically ill may not have been included in our study. This may have resulted in the low rebleeding and mortality rates of our study.

In conclusion, presence of comorbidities, use of multidrugs, albumin levels, and initial presentation with hematemesis/hematochezia were associated with rebleeding and should be carefully investigated for patients triage and management. The wide use of PPI and prompt endoscopic intervention may be the reason for the low rebleeding and mortality rates in Korea.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was granted by National Evidence-based Health-care Collaborating Agency of Korea (HI10C2020).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–113. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisner F, Hermann D, Bajaeifer K, Glatzle J, Königsrainer A, Küper MA. Gastric ulcer complications after the introduction of proton pump inhibitors into clinical routine: 20-year experience. Visc Med. 2017;33:221–226. doi: 10.1159/000475450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494–1499. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkun A, Sabbah S, Enns R, et al. The Canadian Registry on Non-variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Endoscopy (RUGBE): endoscopic hemostasis and proton pump inhibition are associated with improved outcomes in a real-life setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1238–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silverstein FE, Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, Buenger NK, Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:80–93. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(81)73156-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marmo R, Koch M, Cipolletta L, et al. Predicting mortality in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeders: validation of the Italian PNED score and prospective comparison with the Rockall score. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1284–1291. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu PW, Ng EK, Cheung FK, et al. Predicting mortality in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers after therapeutic endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spiegel BM, Ofman JJ, Woods K, Vakil NB. Minimizing recurrent peptic ulcer hemorrhage after endoscopic hemostasis: the cost-effectiveness of competing strategies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:86–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brullet E, Campo R, Calvet X, Guell M, Garcia-Monforte N, Cabrol J. A randomized study of the safety of outpatient care for patients with bleeding peptic ulcer treated by endoscopic injection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:15–21. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)01314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Selection of patients for early discharge or outpatient care after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 1996;347:1138–1140. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saeed ZA, Winchester CB, Michaletz PA, Woods KL, Graham DY. A scoring system to predict rebleeding after endoscopic therapy of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, with a comparison of heat probe and ethanol injection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1842–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hay JA, Lyubashevsky E, Elashoff J, Maldonado L, Weingarten SR, Ellrodt AG. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage clinical--guideline determining the optimal hospital length of stay. Am J Med. 1996;100:313–322. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89490-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345–360. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL., Jr ASA physical status classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:239–243. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet. 1974;2:394–397. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)91770-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkun A, Bardou M, Marshall JK Nonvariceal Upper GI Bleeding Consensus Conference Group. Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:843–857. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García-Iglesias P, Villoria A, Suarez D, et al. Meta-analysis: predictors of rebleeding after endoscopic treatment for bleeding peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:888–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung JJ, Chan FK, Chen M, et al. Asia-Pacific Working Group consensus on non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2011;60:1170–1177. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.230292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang PS, Saltzman JR. A national survey on the initial management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:e93–e98. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar NL, Claggett BL, Cohen AJ, Nayor J, Saltzman JR. Association between an increase in blood urea nitrogen at 24 hours and worse outcomes in acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:1022–1027.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1–a46. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmed A, Armstrong M, Robertson I, Morris AJ, Blatchford O, Stanley AJ. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Scotland 2000–2010: improved outcomes but a significant weekend effect. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10890–10897. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Carvalho Pedroto IM, Azevedo Maia LA, Durão Salgueiro PS, et al. Out-of-hours endoscopy for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:495–502. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.964759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quan S, Frolkis A, Milne K, et al. Upper-gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to peptic ulcer disease: incidence and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17568–17577. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malmi H, Kautiainen H, Virta LJ, Färkkilä MA. Outcomes of patients hospitalized with peptic ulcer disease diagnosed in acute upper endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1251–1257. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin HJ, Lo WC, Lee FY, Perng CL, Tseng GY. A prospective randomized comparative trial showing that omeprazole prevents rebleeding in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer after successful endoscopic therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:54–58. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lee KK, et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:310–316. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Sysntematic review and meta-analysis: enhanced efficacy of proton-pump inhibitor therapy for peptic ulcer bleeding in Asia. A post hoc analysis from the Cochrane Collaboration. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]