Abstract

BACKGROUND

Infection is a leading cause of hospitalization with high morbidity and mortality, but there are limited data to guide the duration of antibiotic therapy.

PURPOSE

Systematic review to compare outcomes of shorter versus longer antibiotic courses among hospitalized adults and adolescents.

DATA SOURCES

MEDLINE and Embase databases, 1990-2017.

STUDY SELECTION

Inclusion criteria were human randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in English comparing a prespecified short course of antibiotics to a longer course for treatment of infection in hospitalized adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older.

DATA EXTRACTION

Two authors independently extracted study characteristics, methods of statistical analysis, outcomes, and risk of bias.

DATA SYNTHESIS

Of 5187 unique citations identified, 19 RCTs comprising 2867 patients met our inclusion criteria, including the following: 9 noninferiority trials, 1 superiority design trial, and 9 pilot studies. Across 13 studies evaluating 1727 patients, no significant difference in clinical efficacy was observed (d = 1.6% [95% confidence interval (CI), −1.0%-4.2%]). No significant difference was detected in microbiologic cure (8 studies, d = 1.2% [95% CI, −4.1%-6.4%]), short-term mortality (8 studies, d = 0.3% [95% CI, −1.2%-1.8%]), longer-term mortality (3 studies, d = −0.4% [95% CI, −6.3%-5.5%]), or recurrence (10 studies, d = 2.1% [95% CI, −1.2%-5.3%]). Heterogeneity across studies was not significant for any of the primary outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the available literature, shorter courses of antibiotics can be safely utilized in hospitalized patients with common infections, including pneumonia, urinary tract infection, and intra-abdominal infection, to achieve clinical and microbiologic resolution without adverse effects on mortality or recurrence.

Acute infections are a leading cause of hospitalization and are associated with high cost, morbidity, and mortality.1 There is a growing body of literature to support shorter antibiotic courses to treat several different infection types.2–6 This is because longer treatment courses promote the emergence of multi-drug resistant (MDR) organisms,7–9 microbiome perturbation,10 and Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).11 They are also associated with more drug side effects, longer hospitalizations, and increased costs.

Despite increasing support for shorter treatment courses, inpatient prescribing practice varies widely, and redundant antibiotic therapy is common.12–14 Furthermore, aside from ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP),15,16 prior systematic reviews of antibiotic duration have typically included outpatient and pediatric patients,3–6,17–19 for whom the risk of treatment failure may be lower.

Given the potential for harm with inappropriate antibiotic treatment duration and the variation in current clinical practice, we sought to systematically review clinical trials comparing shorter versus longer antibiotic courses in adolescents and adults hospitalized for acute infection. We focused on common sites of infection in hospitalized patients, including pulmonary, bloodstream, soft tissue, intra-abdominal, and urinary.20,21 We hypothesized that shorter courses would be sufficient to cure infection and associated with lower costs and fewer complications. Because we hypothesized that shorter durations would be sufficient regardless of clinical course, we focused on studies in which the short course of antibiotics was specified at study onset, not determined by clinical improvement or biomarkers. We analyzed all infection types together because current sepsis treatment guidelines place little emphasis on infection site.22 In contrast to prior reviews, we focused exclusively on adult and adolescent inpatients because the risks of a too-short treatment duration may be lower in pediatric and outpatient populations.

METHODS

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.23 The review was registered on the Prospero database.24

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We performed serial literature searches for articles in English comparing shorter versus longer antibiotics courses in hospitalized patients. We searched MEDLINE via PubMed and Embase (January 1, 1990, to July 1, 2017). We used Boolean operators, Boolean logic, and controlled vocabulary (eg, Medical Subject Heading [MeSH] terms) for each key word. We identified published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of conditions of interest (MeSH terms: “bacteremia,” “sepsis,” “pneumonia,” “pyelonephritis,” “intra-abdominal infection,” “cellulitis,” “soft tissue infection”) that compared differing lengths of antibiotic treatment (keywords: “time factors,” “duration,” “long course,” “short course”) and evaluated outcomes (key words: “mortality,” “recurrence,” “secondary infections”). We hand searched references of included citations. The full search strategy is presented in supplementary Appendix 1.

Study Eligibility and Selection Criteria

To meet criteria for inclusion, a study had to (1) be an RCT; (2) involve an adult or adolescent population age ≥12 years (or report outcomes separately for such patients); (3) involve an inpatient population (or report outcomes separately for inpatients); (4) stipulate a short course of antibiotics per protocol prior to randomization and not determined by clinical response, change in biomarkers, or physician discretion; (5) compare the short course to a longer course of antibiotics, which could be determined either per protocol or by some other measure; and (6) involve antibiotics given to treat infection, not as prophylaxis.

Two authors (SR and HCP) independently reviewed the title and/or abstracts of all articles identified by the search strategy. We calculated interrater agreement with a kappa coefficient. Both authors (SR and HCP) independently reviewed the full text of each article selected for possible inclusion by either author. Disagreement regarding eligibility was adjudicated by discussion.

Data Abstraction

Two authors (SR and HCP) independently abstracted study methodology, definitions, and outcomes for each study using a standardized abstraction tool (see supplementary Appendix 2).

Study Quality

We assessed article quality using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool,25 which evaluates 6 domains of possible bias, including sequence generation, concealment, blinding, and incomplete or selective outcome reporting. The tool is a 6-point scale, with 6 being the best score. It is recommended for assessing bias because it evaluates randomization and allocation concealment, which are not included in other tools.26 We did not exclude studies based on quality but considered studies with scores of 5-6 to have a low overall risk of bias.

Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Our primary outcomes were clinical cure, microbiologic cure, mortality, and infection recurrence. Secondary outcomes were secondary MDR infection, cost, and length of stay (LOS). We conducted all analyses with Stata MP version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). For each outcome, we reported the difference (95% confidence interval [CI]) between treatment arms as the rate in the short course arm minus the rate in the long course arm, consistent with the typical presentation of noninferiority data. When not reported in a study, we calculated risk difference and 95% CI using reported patient-level data. Positive values for risk difference favor the short course arm for favorable outcomes (ie, clinical and microbiologic cure) and the long course arm for adverse outcomes (ie, mortality and recurrence). A meta-analysis was used to pool risk differences across all studies for primary outcomes and for clinical cure in the community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) subgroup. We also present results as odds ratios and risk ratios in the online supplement. All meta-analyses used random effects models, as described by DerSimonian and Laird,27,28 with variance estimates of heterogeneity taken from the Mantel-Haenszel fixed effects model. We investigated heterogeneity between studies using the χ2 I2 statistic. We considered a P < .1 to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity and classified heterogeneity as low, moderate, or high on the basis of an I2 of 25%, 50%, or 75%, respectively. We used funnel plots to assess for publication bias.

RESULTS

Search Results

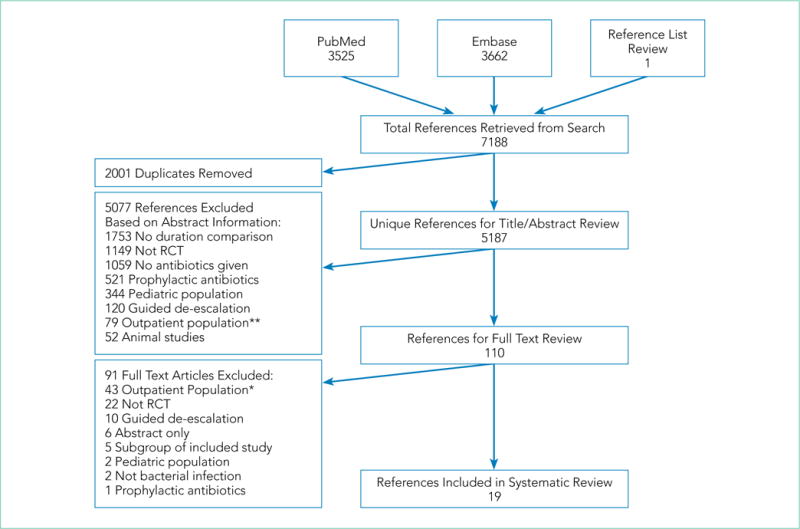

We identified 5187 unique citations, of which 110 underwent full-text review (Figure 1). Reviewer agreement for selection of title and/or abstracts for full evaluation was 99.1% (kappa = 0.71). Nineteen RCTs with a total of 2867 patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis.29–47

FIG 1.

Flow diagram for literature review and study selection. NOTE: **All 79 of these articles included an outpatient-only population. *Twenty-six of these 43 articles were excluded after full-text review because the population contained both inpatients and outpatients but did not provide separate outcomes for the inpatient subgroup. Seventeen articles contained an outpatient-only population. Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Publication years ranged from 1991 to 2015 (Table). Study populations were primarily from Europe (n = 9) or the United States (n = 5). Pneumonia was the most common infection studied, with 3 studies evaluating VAP and 9 studies evaluating CAP. There were also 3 studies of intra-abdominal infections, 2 studies of urinary tract infections (UTIs), 1 study of typhoid fever, and 1 study of hospital-acquired infection of unknown origin. No studies of bacteremia or soft tissue infections met inclusion criteria. Short courses of antibiotics ranged from 1 to 8 days, while long courses ranged from 3 to 15 days.

TABLE.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author | Year | Country | Number of Patientsa |

Patient Location |

Infection Type |

Short Course Antibiotic |

Short Course Duration (days) |

Long Course Antibiotic |

Long Course Duration (days) |

Primary Outcome | Study Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bohte et al.29 | 1995 | Netherlands | 104 | Ward | CAP | Azithromycin | 5 | Erythromycin or benzylpenicillin | 10 or 5 days past last fever | Clinical cure by day 21 | Superiority |

| Capellier et al.30 | 2012 | France | 225 | ICU | VAP | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside | 8 | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside | 15 | Clinical cure at day 21 | Non- inferiority |

| Chastre et al.31 | 2003 | France | 401 | ICU | VAP | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone | 8 | Beta-lactam, aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone | 15 | All-cause mortality at day 28, documented recurrence, antibiotic free days | Non- inferiority |

| Chaudhry et al.32 | 2000 | Pakistan | 50 | Ward | SBP | Cefoperazone | 5 | Cefoperazone | 10 | Infection-related and hospitalization mortalityb | Pilot |

| Darouiche et al.33 | 2014 | USA | 55 | Ward | CA-UTI | Physician discretionc | 5 | Physician discretionc | 10 | Clinical cure at end of therapy (day 5 or 10) | Non- inferiority |

| deGier et al.34 | 1995 | Netherlands | 34 | Ward | c-UTI | Fleroxacin | 7 | Fleroxacin | 14 | Microbiologic cure 4 to 6 weeks post therapyb | Pilot |

| Dunbar et al.35 | 2003 | USA | 162 | Ward, outpatient | CAP | Levofloxacin | 5 | Levofloxacin | 10 | Clinical success at posttherapy (7–14 days after last antibiotics) | Non- inferiority |

| Gasem et al.36 | 2003 | Indonesia | 55 | Ward | Enteric fever | Ciprofloxacin | 7 | Chloramphenicol | 14 | Clinical cure at day 7 | Pilot |

| Kollef et al.37 | 2012 | International | 167 | ICU | VAP | Doripenem | 7 | Imipenem-cilastatin | 10 | Clinical cure at end of therapy (day 10) | Non- inferiority |

| Kuzman et al.38 | 2005 | International | 171 | Ward | CAP | Azithromycin | 4–7 | Cefuroxime | 8–11 | Clinical efficacy at posttreatment (day 10–14) | Pilot |

| Leophonte et al.39 | 2002 | France | 244 | Ward | CAP | Ceftriaxone | 5 | Ceftriaxone | 10 | Apyrexia and no further antibiotics at day 10 | Non- inferiority |

| Rizzato et al.40 | 1995 | Italy | 40 | Ward | CAP | Azithromycin | 3 | Clarithromycin | 8+ | Clinical cure at day 10b | Pilot |

| Runyon et al.41 | 1991 | USA | 90 | Ward | SBP | Cefotaxime | 5 | Cefotaxime | 10 | Hospitalization and all-cause mortalityb | Non- inferiority |

| Sawyer et al.42 | 2015 | USA-Canada | 517 | Ward | Complicated intra- abdominal infection | Physician discretiond | 4 | Physician discretiond | 2 days after resolution of SIRS, maximum 10 days | Composite mortality, surgical-site infection, recurrent intra- abdominal infection | Non- inferiority |

| Scawn et al.43 | 2012 | UK | 46 | ICU | Hospital- acquired infection of unknown origin | Meropenem, teicoplanin | 2 | Meropenem, teicoplanin | 7 | Composite mortality and need for further antibiotics | Pilot |

| Schonwald et al.44 | 1994 | Croatia | 142 | Ward | CAP | Azithromycin | 3 | Roxithromycin | 10 | Clinical cure at day 14 | Pilot |

| Schonwald et al.45 | 1999 | Croatia | 98 | Ward | CAP | Azithromycin | 1 | Azithromycin | 3 | Clinical cure at day 10 to 14 | Pilot |

| Siegel et al.46 | 1999 | USA | 46 | Ward | CAP | Cefuroxime | 7 | Cefuroxime | 10 | Clinical cure at day 10 to 14 | Pilot |

| Zhao et al.47 | 2014 | China | 220 | Ward | CAP | Levofloxacin | 5 | Levofloxacin | 7+ | Overall efficacy at 7 to 14 days post therapy | Non- inferiority |

Number of patients included in primary outcome and/or subset of patients hospitalized.

Primary outcome(s) not specified; outcome(s) discussed first and/or most extensively considered to be primary outcome(s).

Standard choices oral fluoroquinolone and amoxicillin; aztreonam and vancomycin used in patients unable to tolerate oral antibiotics; antibiotic choice based on prior sensitivities if available.

Acceptable if consistent with Surgical Infection Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines.

NOTE: Abbreviations: CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; CA-UTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; c-UTI, complicated urinary tract infection; ICU, intensive care unit; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Common study outcomes included clinical cure or efficacy (composite of symptom cure and improvement; n = 13), infection recurrence (n = 10), mortality (n = 9), microbiologic cure (n = 8), and LOS (n = 7; supplementary Table 1).

Nine studies were pilot studies, 1 was a traditional superiority design study, and 9 were noninferiority studies with a prespecified limit of equivalence of either 10% (n = 7) or 15% (n = 2).

Clinical Cure and Efficacy

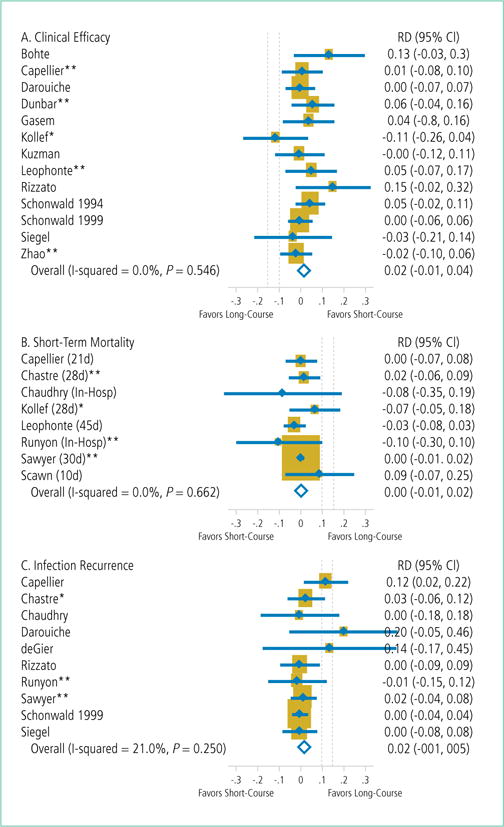

Thirteen studies of 1727 patients evaluated clinical cure and efficacy (Figure 2).29,30,33,35-40,44-47 The overall risk difference was d = 1.6% (95% CI, −1.0%-4.2%), and the pooled odds ratio was 1.11 (95% CI, 0.85-1.45; supplementary Table 2). There was no heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = .55). Five of 6 studies with a noninferiority design met their prespecified margin, while 1 study of VAP failed to meet the 15% noninferiority margin (d = −11.2% [95% CI, −26.3%-3.8%]).37

FIG 2.

Forest plots (clinical efficacy, short-term mortality, infection recurrence). NOTE: Fifteen percent was used as the limit of equivalence for the difference between short-course and long-course groups in 2 studies (Kollef et al.37 and Runyon et al41). Ten percent was used as the limit of equivalence for the difference between short-course and long-course groups in 7 studies (Capellier et al.,30 Chastre et al.,31 Darouiche et al.,33 Dunbar et al.,35 Leophonte et al,39 Sawyer et al,42 and Zhao et al.47). For favorable outcomes (eg, clinical efficacy), positive values favor the short-course arm, and the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval must be >−10% or >−15% to confirm noninferiority. For adverse outcomes (eg, mortality and infection recurrence), negative values favor the short course group, and the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval must be <10% or <15% to confirm noninferiority. **Met prespecified noninferiority margin. *Evaluated noninferiority but did not meet prespecified margin.

Nine studies of 1225 patients evaluated clinical cure and efficacy in CAP (supplementary Figure 1).29,35,38–40,44–47 The overall risk difference was d = 2.4% (95% CI, −0.7%-5.5%). There was no heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = .45).

Microbiologic Cure

Eight studies of 366 patients evaluated microbiologic cure (supplementary Figure 2).32-34,36,38,40,41,47 The overall risk difference was d = 1.2% (95% CI, −4.1%-6.4%). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 13.3%, P = .33).

Mortality

Eight studies of 1740 patients evaluated short-term mortality (in hospital to 45 days; Figure 2),30–32,37,39,41,43 while 3 studies of 654 patients evaluated longer-term mortality (60 to 180 days; supplementary Figure 3).30,31,33 The overall risk difference was d = 0.3% (95% CI, −1.2%-1.8%) for short-term mortality and d = −0.4% (95% CI, −6.3%-5.5%) for longer-term mortality. There was no heterogeneity between studies for either short-term (I2 = 0.0%, P = .66) or longer-term mortality (I2 = 0.0%, P = .69).

Infection Recurrence

Ten studies of 1554 patients evaluated infection recurrence (Figure 2).30–34,40–42,45,46 The overall risk difference was d = 2.1% (95% CI, −1.2%-5.3%). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 21.0%, P = .25). Two of the 3 studies with noninferiority design (both evaluating intra-abdominal infections) met their prespecified margins.41,42 In Chastre et al.,31 the overall population (d = 3.0%; 95% CI, −5.8%-11.7%) and the subgroup with VAP due to nonfermenting gram-negative bacilli (NF-GNB; d = 15.2%; 95% CI, −0.9%-31.4%) failed to meet the 10% noninferiority margin.

Secondary Outcomes

Three studies30,31,42 of 286 patients (with VAP or intra-abdominal infection) evaluated the emergence of MDR organisms. The overall risk difference was d = −9.0% (95% CI, −19.1%-1.1%; P = .081). There was no statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 7.6%, P = .34).

Seven studies examined LOS—3 in the intensive care unit (ICU)30,31,43 and 4 on the wards32,36,40,41—none of which found significant differences between treatment arms. Across 3 studies of 672 patients, the weighted average for ICU LOS was 23.6 days in the short arm versus 22.2 days in the long arm. Across 4 studies of 235 patients, the weighted average for hospital LOS was 23.3 days in the short arm versus 29.7 days in the long arm. This difference was driven by a 1991 study41 of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), in which the average LOS was 37 days and 50 days in the short- and long-course arms, respectively.

Three studies32,41,43 of 186 total patients (with SBP or hospital-acquired infection of unknown origin) examined the cost of antibiotics. The weighted average cost savings for shorter courses in 2016 US dollars48 was $265.19.

Three studies30,33,43 of 618 patients evaluated cases of CDI, during 10-, 30-, and 180-day total follow-up. The overall risk difference was d = 0.7% (95% CI, −1.3%-2.8%), with no statistically significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 0%, P = .97).

Study Quality

Included studies scored 2-5 on the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (supplementary Figure 4). Four studies had an overall low risk of bias,36,37,43,46 while 15 had a moderate to high risk of bias (supplementary Table 3).29–35,38–42,44,45,47 Common sources of bias included inadequate details to confirm adequate randomization and/or concealment (n = 13) and lack of adequate blinding (n = 18). Two studies were stopped early,37,42 and 3 others were possibly stopped early because it was unclear how the number of participants was determined.29,33,47 Covariate imbalance (failure of randomization) was present in 2 studies.37,47 There was no evidence of selective outcome reporting or publication bias based on the funnel plots (supplementary Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of shorter versus longer antibiotic courses for adults and adolescents hospitalized for infection. The rate of clinical cure was indistinguishable between patients randomized to shorter versus longer durations of antibiotic therapy, and the meta-analysis was well powered to confirm noninferiority. The lower 95% CI indicates that any potential benefit of longer antibiotics is not more than 1%, far below the typical margin of noninferiority. Subgroup analysis of patients hospitalized with CAP also showed noninferiority of a prespecified shorter treatment duration.

The rate of microbiologic cure was likewise indistinguishable, and the meta-analysis was again well powered to confirm noninferiority. Any potential benefit of longer antibiotics for microbial cure is quite small (not more than 4%).

Our study also demonstrates noninferiority of prespecified shorter antibiotic courses for mortality. Shorter- and longer-term mortality were both indistinguishable in patients randomized to shorter antibiotic courses. The meta-analyses for mortality were well powered, with any potential benefit of longer antibiotic durations being less than 2% for short-term and less than 6% for long-term mortality.

We also examined for complications related to antibiotic therapy. Infection recurrence was indistinguishable, with any potential benefit of longer antibiotics being less than 6%. Select infections (eg, VAP due to NF-GNB, catheter-associated UTI) may be more susceptible to relapse after shorter treatment courses, while most patients hospitalized with infection do not have an increased risk for relapse with shorter treatment courses. Consistent with other studies,8 the emergence of MDR organisms was 9% less common in patients randomized to shorter antibiotic courses. This difference failed to meet statistical significance, likely due to poor power. The emergence of MDR pathogens was included in just 3 of 19 studies, underscoring the need for additional studies on this outcome.

Although our meta-analyses indicate noninferiority of shorter antibiotic courses in hospitalized patients, the included studies are not without shortcomings. Only 4 of the included studies had low risk of bias, while 15 had at least moderate risk. The nearly universal source of bias was a lack of blinding. Only 1 study37 was completely blinded, and only 3 others had partial blinding. Adequate randomization and concealment were also lacking in several studies. However, there was no evidence of selective outcome reporting or publication bias.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies indicating non-inferiority of shorter antibiotic courses in other settings and patient populations. Pediatric studies have demonstrated the success of shorter antibiotic courses in both outpatient49 and inpatient populations.50 Prior meta-analyses have shown non-inferiority of shorter antibiotic courses in adults with VAP15,16; in neonatal, pediatric, and adult patients with bacteremia17; and in pediatric and adult patients with pneumonia and UTI.3–6,18,19 Our meta-analysis extends the evidence for the safety of shorter treatment courses to adults hospitalized with common infections, including pneumonia, UTI, and intra-abdominal infections. Because neonatal, pediatric, and nonhospitalized adult patients may have a lower risk for treatment failure and lower risk for mortality in the event of treatment failure, we focused exclusively on hospitalized adults and adolescents.

In contrast to prior meta-analyses, we included studies of multiple different sites of infection. This allowed us to assess a large number of hospitalized patients and achieve a narrow margin of noninferiority. It is possible that the benefit of optimal treatment duration varies by type of infection. (And indeed, absolute duration of treatment differed across studies.) We used a random-effects framework, which recognizes that the true benefit of shorter versus longer duration may vary across study populations. The heterogeneity between studies in our meta-analysis was quite low, suggesting that the results are not explained by a single infection type.

There are limited data on late effects of longer antibiotic courses. Antibiotic therapy is associated with an increased risk for CDI for 3 months afterwards.11 However, the duration of follow-up in the included studies rarely exceeded 1 month, which could underestimate incidence. The effect of antibiotics on gut microbiota may persist for months, predisposing patients to secondary infections. It is plausible that disruption in gut microbiota and risk for CDI may persist longer in patients treated with longer antibiotic courses. However, the existing studies do not include sufficient follow-up to confirm or refute this hypothesis.

Our review has several limitations. First, we included studies that compared an a priori-defined short course of antibiotics to a longer course and excluded studies that defined a short course of antibiotics based on clinical response. Because we did not specify an exact length for short or long courses, we cannot make explicit recommendations about the absolute duration of antibiotic therapy. Second, we included multiple infection types. It is possible that the duration of antibiotics required may differ by infection type. However, there were not sufficient data for subgroup analyses for each infection type. This highlights the need for additional data to guide the treatment of severe infections. Third, not all studies considered antibiotic duration in isolation. One study included a catheter change in the short arm only, which could have favored the short course.33 Three studies used different doses of antibiotics in addition to different durations.35,45,47 Fourth, the quality of included studies was variable, with lack of blinding and inadequate randomization present in most studies.

CONCLUSION

Based on the available literature, shorter courses of antibiotics can be safely utilized in hospitalized adults and adolescents to achieve clinical and microbiologic resolution of common infections, including pneumonia, UTI, and intra-abdominal infection, without adverse effect on infection recurrence. Moreover, short- and longer-term mortality are indistinguishable after treatment courses of differing duration. There are limited data on the longer-term risks associated with antibiotic duration, such as secondary infection or the emergence of MDR organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their research librarian, Marisa Conte, for her help with the literature search for this review.

Drs. Royer and Prescott designed the study, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Drs. DeMerle and Dickson revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. Dr. Royer holds stock in Pfizer. This work was supported by K08 GM115859 [HCP]. This manuscript does not necessarily represent the position or policy of the US government or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Disclosure: The authors have no other potential financial conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Torio CM, Andrews RM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011: Statistical Brief #160. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb160.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(5):575–582. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Grammatikos AP, Athanassa Z, Falagas ME. Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia : a meta-analysis. Drugs. 2008;68(13):1841–1854. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200868130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S. Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eliakim-Raz N, Yahav D, Paul M, Leibovici L. Duration of antibiotic treatment for acute pyelonephritis and septic urinary tract infection– 7 days or less versus longer treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(10):2183–2191. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyriakidou KG, Rafailidis P, Matthaiou DK, Athanasiou S, Falagas ME. Short-versus long-course antibiotic therapy for acute pyelonephritis in adolescents and adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Ther. 2008;30(10):1859–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spellberg B, Bartlett JG, Gilbert DN. The future of antibiotics and resistance. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):299–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spellberg B. The New Antibiotic Mantra-“Shorter Is Better”. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1254–1255. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice LB. The Maxwell Finland Lecture: for the duration-rational antibiotic administration in an era of antimicrobial resistance and clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(4):491–496. doi: 10.1086/526535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4554–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hensgens MP, Goorhuis A, Dekkers OM, Kuijper EJ. Time interval of increased risk for Clostridium difficile infection after exposure to antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(3):742–748. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huttner B, Jones M, Huttner A, Rubin M, Samore MH. Antibiotic prescription practices for pneumonia, skin and soft tissue infections and urinary tract infections throughout the US Veterans Affairs system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(10):2393–2399. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daneman N, Shore K, Pinto R, Fowler R. Antibiotic treatment duration for bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: a national survey of Canadian infectious diseases and critical care specialists. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38(6):480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schultz L, Lowe TJ, Srinivasan A, Neilson D, Pugliese G. Economic impact of redundant antimicrobial therapy in US hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(10):1229–1235. doi: 10.1086/678066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimopoulos G, Poulakou G, Pneumatikos IA, Armaganidis A, Kollef MH, Matthaiou DK. Short- vs long-duration antibiotic regimens for ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2013;144(6):1759–1767. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pugh R, Grant C, Cooke RP, Dempsey G. Short-course versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy for hospital-acquired pneumonia in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD007577. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007577.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havey TC, Fowler RA, Daneman N. Duration of antibiotic therapy for bacte-remia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R267. doi: 10.1186/cc10545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haider BA, Saeed MA, Bhutta ZA. Short-course versus long-course antibiotic therapy for non-severe community-acquired pneumonia in children aged 2 months to 59 months. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005976. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005976.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strohmeier Y, Hodson EM, Willis NS, Webster AC, Craig JC. Antibiotics for acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):Cd003772. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003772.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leligdowicz A, Dodek PM, Norena M, et al. Association between source of infection and hospital mortality in patients who have septic shock. Am J Re-spir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(10):1204–1213. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1875OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cagatay AA, Tufan F, Hindilerden F, et al. The causes of acute Fever requiring hospitalization in geriatric patients: comparison of infectious and noninfectious etiology. J Aging Res. 2010;2010:380892. doi: 10.4061/2010/380892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486–552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269 W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Royer S, DeMerle K, Dickson RP, Prescott HC. Shorter versus longer courses of antibiotics for infection in hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO. 2016 doi: 10.12788/jhm.2905. CRD42016029549. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016029549. Accessed May 2, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner L, Boutron I, Hróbjartsson A, Altman DG, Moher D. The evolution of assessing bias in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions: celebrating methodological contributions of the Cochrane Collaboration. Syst Rev. 2013;2:79. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newton HJ, Cox NJ, Diebold FX, Garrett HM, Pagano M, Royston JP, editors. Stata Technical Bulletin. 44:sbe24. http://www.stata.com/products/stb/journals/stb44.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bohte R, van’t Wout JW, Lobatto S, et al. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin versus benzylpenicillin or erythromycin in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14(3):182–187. doi: 10.1007/BF02310353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Capellier G, Mockly H, Charpentier C, et al. Early-onset ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults randomized clinical trial: comparison of 8 versus 15 days of antibiotic treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e41290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chastre J, Wolff M, Fagon JY, et al. Comparison of 8 vs 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2588–2598. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaudhry ZI, Nisar S, Ahmed U, Ali M. Short course of antibiotic treatment in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A randomized controlled study. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan. 2000;10(8):284–288. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darouiche RO, Al Mohajer M, Siddiq DM, Minard CG. Short versus long course of antibiotics for catheter-associated urinary tract infections in patients with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(2):290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Gier R, Karperien A, Bouter K, et al. A sequential study of intravenous and oral Fleroxacin for 7 or 14 days in the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1995;6(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(95)00011-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunbar LM, Wunderink RG, Habib MP, et al. High-dose, short-course levo-floxacin for community-acquired pneumonia: a new treatment paradigm. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(6):752–760. doi: 10.1086/377539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gasem MH, Keuter M, Dolmans WM, Van Der Ven-Jongekrijg J, Djokomo-eljanto R, Van Der Meer JW. Persistence of Salmonellae in blood and bone marrow: randomized controlled trial comparing ciprofloxacin and chloram-phenicol treatments against enteric fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(5):1727–1731. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.5.1727-1731.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kollef MH, Chastre J, Clavel M, et al. A randomized trial of 7-day doripenem versus 10-day imipenem-cilastatin for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care. 2012;16(6):R218. doi: 10.1186/cc11862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuzman I, Daković-Rode O, Oremus M, Banaszak AM. Clinical efficacy and safety of a short regimen of azithromycin sequential therapy vs standard cefuroxime sequential therapy in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: an international, randomized, open-label study. J Chemother. 2005;17(6):636–642. doi: 10.1179/joc.2005.17.6.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Léophonte P, Choutet P, Gaillat J, et al. Efficacy of a ten day course of ceftri-axone compared to a shortened five day course in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized adults with risk factors. Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2002;32(7):369–381. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizzato G, Montemurro L, Fraioli P, et al. Efficacy of a three day course of azi-thromycin in moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1995;8(3):398–402. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Runyon BA, McHutchison JG, Antillon MR, Akriviadis EA, Montano AA. Short-course versus long-course antibiotic treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A randomized controlled study of 100 patients. Gastroenter-ology. 1991;100(6):1737–1742. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90677-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sawyer RG, Claridge JA, Nathens AB, et al. Trial of short-course antimicrobial therapy for intraabdominal infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):1996–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scawn N, Saul D, Pathak D, et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial in intensive care patients comparing 7 days’ treatment with empirical antibiotics with 2 days’ treatment for hospital-acquired infection of unknown origin. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(36):i–xiii. 1–70. doi: 10.3310/hta16360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schönwald S, Barsić B, Klinar I, Gunjaca M. Three-day azithromycin compared with ten-day roxithromycin treatment of atypical pneumonia. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26(6):706–710. doi: 10.3109/00365549409008639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schönwald S, Kuzman I, Oresković K, et al. Azithromycin: single 1.5 g dose in the treatment of patients with atypical pneumonia syndrome–a randomized study. Infection. 1999;27(3):198–202. doi: 10.1007/BF02561528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegel RE, Alicea M, Lee A, Blaiklock R. Comparison of 7 versus 10 days of antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Am J Ther. 1999;6(4):217–222. doi: 10.1097/00045391-199907000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao X, Wu JF, Xiu QY, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of levoflox-acin 750 mg versus 500 mg intravenous infusion in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;80(2):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bureau of Economic Analysis, U.S. Department of Commerce. https://bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=9&step=1#reqid=9&step=1&isuri=1&903=4. Accessed March 2, 2017.

- 49.Pakistan Multicentre Amoxycillin Short Course Therapy (MASCOT) pneumonia study group. Clinical efficacy of 3 days versus 5 days of oral amoxicillin for treatment of childhood pneumonia: a multicentre double-blind trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9336):835–841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09994-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peltola H, Vuori-Holopainen E, Kallio MJ, SE-TU Study Group Successful shortening from seven to four days of parenteral beta-lactam treatment for common childhood infections: a prospective and randomized study. Int J Infect Dis. 2001;5(1):3–8. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(01)90041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.