Abstract

Maternal depression is among the most consistent and well-replicated risk factors for negative child outcomes, particularly in early childhood. Although children of depressed mothers are at an increased risk of adjustment problems, conversely, children with emotional or behavioral problems also have been found to adversely compromise maternal functioning, including increasing maternal depression. The purpose of this investigation was to examine transactional associations among maternal depression, parent–child coercive interaction, and children’s conduct and emotional problems in early childhood using a cross-lagged panel model. Participants were 731 toddlers and families that were part of the Early Steps Multisite Study, a sample of diverse ethnic backgrounds and communities (i.e., rural, urban, suburban) recruited from Women, Infants, and Children Nutritional Supplement Centers. Analyses provided support for the existence of some modest transactional relations between parent–child coercion and maternal depression and between maternal depression and child conduct problems. Cross-lagged effects were somewhat stronger between children age 2–3 than age 3–4. Similar patterns were observed in the model with child emotional problems replacing conduct problems, but relations between coercion and maternal depression were attenuated in this model. In addition, the transactional hypothesis was more strongly supported when maternal versus secondary caregiver reports were used for child problem behavior. The findings have implications for the need to support caregivers and reinforce positive parenting practices within family-centered interventions in early childhood.

Maternal depression affects approximately 17% of mothers of young children (Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe, Lyubchik, & Steingard, 2002; McLennan, Kotelchuck, & Cho, 2001), with rates approaching 50% among low-income mothers of young children (Chung, McCollum, Elo, Lee, & Culhane, 2004; Hall, Williams, & Greenberg, 1985; Ramos-Marcuse et al., 2010). Beyond its considerable prevalence and effects on mothers themselves, maternal depression is among the most robust and well-replicated risk factors for a host of negative child outcomes (Cummings & Davies, 1994; Gelfand & Teti, 1990; Goodman et al., 2011).

MATERNAL DEPRESSION AND CHILD ADJUSTMENT

Studies of children of depressed mothers have focused on both homotypic links between maternal and child depression (Goodman et al., 2011) and heterotypic connections between maternal depression and other problems, such as child difficult temperament (Hanington, Ramchandani, & Stein, 2010), insecure attachment (Campbell et al., 2004; Field et al., 1988), conduct problems (Marchand, Hock, & Widaman, 2002; Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, 1994), and reduced cognitive and motor development (Evans et al., 2012; Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper, & Cooper, 1996; Sharp et al., 1995). As both clinical depression and maternal depressive symptoms have been linked to child psychopathology (Cummings, Keller, & Davies, 2005; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Kouros & Garber, 2010; Weinfield, Ingerski, & Moreau, 2009), “maternal depression” will be used in reference to studies that measured depression using diagnostic criteria or symptom counts.

The current study will focus on conduct problems (CP) for several reasons. First, CP, which represents a range of heterotypically similar externalizing symptoms, are the most common forms of child maladjustment (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000). Second, early onset of CP is associated with more serious forms of antisocial behavior in later childhood and adolescence (Aguilar, Sroufe, Egeland, & Carlson, 2000; Odgers et al., 2008); hence, it is important to identify early risk factors of CP in the interest of informing effective prevention and intervention efforts. Finally, the developmental period of interest, the toddler period, represents a time when children are more likely to develop CP when exposed to maternal depression than are older children, perhaps because of their greater psychological and physical dependence on caregivers relative to older children (Bagner, Pettit, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 2010; Connell & Goodman, 2002; Cummings & Davies, 1994).

The toddler period is particularly challenging for parents because of children’s rapid increase in physical mobility and lack of understanding of the consequences of their behavior (Keenan & Shaw, 1995; Shaw et al., 1994; Shaw et al., 1998). Consistent with the challenges of managing a more physically mobile but cognitively limited child during the 2nd year, parental pleasure in childrearing decreases from 12 to 18 months (Fagot & Kavanagh, 1993). Thus, as the toddler period represents a time of developmental transition for both child and parent, it is a critical juncture to examine the interplay between maternal well-being and child CP (Choe, Shaw, Brennan, Dishion, & Wilson, 2014; Gelfand & Teti, 1990; Gross, Shaw, Burwell, & Nagin, 2009).

Although children of depressed mothers are at an increased risk of adjustment problems, living with a child with emotional or behavioral disturbances may have reciprocal adverse consequences on maternal functioning and thus theoretically could increase the risk of or exacerbate maternal depression (Bell, 1968). The stress of having a child with clinically meaningful levels of problem behavior has been hypothesized to contribute to the onset and exacerbation of a mother’s depressive symptoms (Feske et al., 2001; Hammen, 1991, 1992). Civic and Holt (2000) found that mothers who reported three or more adjustment problems in their children (e.g., temper tantrums, social problems, unhappiness) were 3.6 times more likely than other mothers to show elevated scores on a self-report screen for depression. Experimental evidence consistent with possible evocative effects on maternal functioning also comes from studies in which improvements in child and adolescent behavior problems following treatment have been associated with decreases in maternal depressive symptoms (Bagner & Eyberg, 2003; Grimbos & Granic, 2009).

Taking a transactional approach to understanding the development of child CP is important because of established associations between parenting and child factors over time (Patterson, 1982; Sameroff, 2009), particularly in early childhood (Shaw et al., 1998). Measuring child psychopathology from a unidirectional perspective in which child influences on parenting behavior are ignored fails to consider such bidirectional effects and how individual differences in child behavior might influence child outcomes by eliciting variation in parenting behavior (Bell, 1968; Shaw & Bell, 1993). Transactional models of analysis emphasize the “bidirectional, interdependent effects of the child and environment” (Sameroff, 2009) and require a minimum of two assessment points.

Transactional associations between maternal depression and child problem behavior and between child problem behavior and maternal depression have been found within the same study (Elgar, McGrath, Waschbusch, Stewart, & Curtis, 2004). For example, in a study of at-risk boys, Gross et al. (2009) found that disruptive behavior in toddlerhood was associated with persistently high levels of maternal depressive symptoms, which in turn predicted youth antisocial behavior in adolescence. Using data from the current sample, both short-term and longer term reciprocal effects between child CP and maternal depression have been demonstrated (Choe et al., 2014; Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion, & Wilson, 2008). Thus, mothers’ and children’s psychopathology have been shown to mutually influence each other over time during the toddler and preschool periods.

Some research suggests that a portion of the variance in the association between maternal depression and child CP may be attributable to a bias in reporting, where mothers experiencing depressive symptoms are more likely to have a negative view of their children’s behavior, and thus report more problematic behavior in their children than mothers with fewer symptoms of depression (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1993; Goodman et al., 2011; Gross et al., 2009). However, some more recent studies suggest that effects of maternal depressive symptoms on reporting of child behavior may be quite modest (De Los Reyes et al., 2015). A meta-analysis of 193 studies found that the source of data on child outcomes affected the strength of the association between maternal depression and child emotional and behavioral problems (Goodman et al., 2011), with studies relying on mothers’ reports of child behavior having significantly larger effect sizes than studies relying on teacher reports, child reports, or mother–child combined reports of child behavior. Although this meta-analytic finding could be evidence of a reporting bias in depressed mothers, it could also reflect that children interacting with their depressed mothers have higher levels of problem behavior. In addition, there is strong evidence suggesting that children’s behavior can vary substantially depending on the context and environment (De Los Reyes, Thomas, Goodman, & Kundey, 2013). Thus, it is crucial, when possible, to obtain information from multiple reporters across contexts.

Maternal Depression and Parent–Child Coercion

Although there is substantial evidence to suggest that maternal depression is associated with many types of impaired parenting (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Murray et al., 1996; Shaw & Shelleby, 2014), the current study focuses on coercive parenting because of its established association with maternal depression and subsequent child CP. Children are likely to elicit more coercive caregiving behaviors in a depressed relative to a nondepressed parent, and previous research suggests that it is possible to trace the unfolding of coercive parent–child interaction as predicted by individual differences in maternal depression during the toddler period. A meta-analysis of 46 observational studies showed a moderate association between maternal depression and parenting behavior in the domain of negative behavior, such that irritable, critical, and coercive elements of parenting were strongly associated with maternal depression (Lovejoy et al., 2000). With toddler and preschool-age children, depressed mothers are more frequently oriented toward coercion, retaliation, and revenge than are nondepressed mothers (Kochanska, Kuczynski, & Maguire, 1989).

Few studies have investigated whether parent–child coercion is associated with high levels of maternal depression. Despite the paucity of empirical support, interpersonal theories of depression suggest that depressed individuals act in ways that elicit rejection and stress in their relationships; these disturbances would then be theorized to perpetuate depression. For example, Coyne’s (1976) pioneering theory articulates an escalating cycle of interpersonal disturbances and depressive symptoms. Similarly, Hammen’s (1991, 1992, 2006) stress-generation theory proposes that characteristics and behaviors of depressed individuals create stress and conflict in their relationships, thereby contributing to subsequent depression. Thus, it is likely that high levels of parent–child coercion would be associated with increased levels of maternal depressive symptoms, particularly during a time of children’s developmental transition during the “terrible twos” (Shaw & Bell, 1993).

Parent–Child Coercion and Child CP

There is compelling evidence from longitudinal and intervention studies that harsh, coercive parenting contributes to child CP (Patterson, 2002; Pettit & Arsiwalla, 2008). Theories linking parenting to children’s CP emphasize how harsh and overreactive parenting reinforces angry emotions (Dix, 1991; Scaramella & Leve, 2004), distresses children (O’Leary, Slep, & Reid, 1999), and affects children’s ability to regulate their emotions (Eisenberg et al., 1999). It also appears that parents who use harsh and coercive strategies when confronting child misbehaviors inadvertently foster further aggressive and disruptive behavior. Negative reinforcement underlies the tendency for relatively minor problem behaviors in young children to become more frequent and serious in the context of the family (Patterson, 1982, 2016; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992).

There has been some empirical support for reciprocal influences between parent–child coercion and child CP, albeit predominantly coming from longitudinal studies conducted with school-age children and adolescents. For example, Burke, Pardini, and Loeber (2008) found that child CP were more consistently predictive of subsequent parenting than parenting was predictive of subsequent CP and more serious forms of antisocial behavior from ages 7–17. In a study with children closer to the age of those in the current sample, Larsson and colleagues (2008) examined transactional links between parental negativity and child CP in a genetically informed twin design of children ages 4 and 7. Comparable effect sizes were found for child → parent and parent → child effects. Finally, Verhoeven, Junger, Van Aken, Deković, and Van Aken (2010) examined the bidirectional relationship between parenting and boys’ CP in a four-wave longitudinal study of toddlers (ages 17, 23, 29, and 35 months). Results showed that although parenting did not predict boys’ later CP, boys’ CP predicted parent-reported support, lack of structure, psychological control, and physical punishment. In sum, although reciprocal associations between parenting and CP have been studied, relatively little is known about bidirectional associations between parenting and CP across toddlerhood when coercive patterns of parent–child interaction are thought to originate (Patterson, 1982; Shaw & Bell, 1993; Tremblay et al., 2004).

Although child disruptive behavior problems have been much more comprehensively studied with respect to parent– child coercion, there is reason to believe that child emotional problems could similarly lead to increases in both maternal depressive symptoms and coercive parenting. As young children’s internalizing problems are also characterized by expressions of emotion dysregulation (e.g., crying, fear-based tantrums), such stress on parents could easily lead to increases in maternal depressive symptoms and coercive interactions with children. Similarly, coercive and hostile parenting has been linked to both child externalizing and internalizing problems (Caron, Weiss, Harris, and Catron (2006), suggesting the possibility of transactional processes among child internalizing, maternal depression, and coercive interactions.

CURRENT STUDY

The purpose of this investigation was to examine transactional associations among maternal depression, coercive parent-child interactions, and child CP during early childhood. The cross-lagged panel design afforded the opportunity to explore multiple transactional relations between maternal depression and child CP, maternal depression and parent-child coercion, and parent-child coercion and child CP. A final aim of the current sFtudy was to establish whether these transactional relations are specific to children’s CP or whether child emotional problems are also implicated. The sample includes 731 toddlers identified to be at risk for developing early-starting CP on the basis of socioeconomic, family, and child risk who were part of a randomized intervention trial to test the effectiveness of a family-centered preventive intervention, the Family Check-Up (FCU). The following hypotheses guided the current study. First, high levels of maternal depressive symptoms were expected to be positively related to subsequent levels of parent-child coercion. Second and similarly, we hypothesized that high levels of parent-child coercion would predict subsequent elevations in maternal depressive symptoms. Third, based on some prior evidence (Verhoeven et al., 2010) of stronger child to parenting effects than parenting to child effects during early childhood, we hypothesized that parent-child coercion would be more strongly related to child CP than child CP would be related to parent-child coercion. Fourth, we predicted that transactional patterns between maternal depression and child CP would be stronger from age 2–3 than from age 3–4, because of the high levels of maternal depression and problem behavior during toddlerhood relative to other age periods. To determine whether patterns observed are specific to child CP rather than reflecting a more generalized effect on child psychopathology, we conducted analyses for parallel models replacing child CP with internalizing symptoms.

METHOD

Participants

Participants included 731 mother–child dyads recruited between 2002 and 2003 from Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Nutritional Supplement Program sites in the metropolitan areas of Pittsburgh, PA, and Eugene, OR, and within and outside the town of Charlottesville, VA (Dishion et al., 2008). Families were approached at WIC sites and invited to participate if they had a son or daughter between 2 years 0 months and 2 years 11 months of age, following a screen to ensure that they met the study criteria by having socioeconomic, family, and/or child risk factors for future behavior problems. Risk criteria for recruitment were defined at or above 1 standard deviation above normative averages on several screening measures within the following three domains: (a) child behavior (CP, high-conflict relationships with adults), (b) family problems (maternal depression, daily parenting challenges, substance use problems, teen parent status), and (c) sociodemographic risk (low education achievement and low family income using WIC criterion). At least two of the three risk factors were required for inclusion in the sample.

Of the 1,666 parents approached across the three study sites who had children in the appropriate age range, 879 families met the eligibility requirements (52% in Pittsburgh, 57% in Eugene, 49% in Charlottesville) and 731 (83.2%) agreed to participate (88% in Pittsburgh, 84% in Eugene, 76% in Charlottesville). Of the 731 families, 272 (37%) were recruited in Pittsburgh, 271 (37%) in Eugene, and 188 (26%) in Charlottesville. More participants were recruited in Pittsburgh and Eugene due to larger populations of eligible families in these regions relative to Charlottesville.

Across sites, the children were reported to identify with the following racial groups: 27.9% African American, 50.1% European American, 13.0% biracial, and 8.9% other races (e.g., American Indian, native Hawaiian). Thirteen percent of the sample reported being of Hispanic ethnicity. During the period of screening, more than two thirds of those families enrolled in the project had an annual income of less than $20,000, and the average number of family members per household was 4.5 (SD = 1.63). Forty-one percent of the primary caregivers in the sample had a high school diploma or GED equivalency, and an additional 32% had 1–2 years of post–high school training.

Of the 731 families who participated in the initial study assessment at age 2, 659 (90%) completed the age 3 assessment and 619 (85%) took part in the age 4 study visit. Selective attrition analyses suggested that there were no significant differences in retention rates across project site, child race, ethnicity, or gender, maternal depression, or children’s externalizing behaviors.

Sample Reduction

Of the 731 original families, 650 participants were selected for the current study, in which the primary caregiver (PC) remained the same over the three assessment periods (ages 2, 3, and 4). Data were carefully screened to ensure that the PC was the same person over time to model stability across time and transactional relationships within the same person. The vast majority of PCs (97.4%) were children’s biological mothers.

Secondary caregivers (SCs) were included at each assessment to obtain information about the child’s behavior from a second informant. At the age 2 assessment, 377 secondary caregivers (58%) participated; 51% were biological fathers, 22% were grandmothers, 6% were mothers’ boyfriends, 6% were aunts, and the remaining 15% were identified as other. These percentages remained similar at subsequent assessment times, with 45%–53% of SCs participating, of which 39%–46% were biological fathers, 20% were grandmothers, 9% were mothers’ boyfriends, 8% were aunts, and 17%– 24% were designated as other. Families for whom SC report was available did not differ from families for whom SC report was not available on levels of maternal depression at age 2 or PC-reported child externalizing at age 2. Levels of parent–child coercion at age 2 were lower in families with a SC (t = 3.12, p < .01).

Children were White (47%), African American (28%), or biracial (11%), and the remaining children were identified as other (e.g., Native American). Participants resided in or around three U.S. cities: 25% lived in Charlottesville, 37% lived in Eugene, and 37% lived in Pittsburgh. Mothers on average were high school graduates, but their education levels ranged from seventh grade or less to college graduates. Because this sample was derived from a prevention study, 325 families (50%) participated in a family-based intervention.

There were no statistically reliable differences between the full and current samples in site location; treatment group; child gender; relative risk (income, maternal education); child race; Hispanic ethnicity; ages 2, 3, and 4 levels of maternal depressive symptoms; child CP (PC and SC reports); and dyadic coercion.

Procedure

Home Observation Assessment Protocol

Caregivers who agreed to participate in the study were scheduled for a 2.5-hr home visit. The assessment began with a 15-min free play in which children were introduced to an assortment of age-appropriate toys while caregivers completed questionnaires. Children then engaged in a series of structured tasks with their parents (e.g., cleanup, delay of gratification, teaching tasks) or the examiner (e.g., language test, effortful control tasks). Similar procedures were repeated at ages 3 and 4. For the age 2 home assessment, families were reimbursed $100 for their participation. They received $120 and $140 for the assessments at ages 3 and 4, respectively.

Families were randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. Examiners who administered follow-up assessments were unaware of the family’s assigned condition. For a detailed description of the intervention, see Dishion et al. (2008). Because intervention group status was not a focus of the current study, it was used as a covariate in all analyses.

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

A demographics questionnaire was administered to the primary caregivers at every annual visit. The current study included age 2 assessments of the following variables as covariates in main analyses: child gender and race (i.e., White, Black, or other), child ethnicity (Hispanic or other), intervention status, geographic site, and mothers’ education level (high school graduate or not).

Maternal Depression

Center for Epidemiological Studies on Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) is a well-established and widely used 20-item measure of depressive symptomatology that was administered at each assessment. Participants reported how frequently they experienced a list of depressive symptoms during the past week on a scale ranging from 0 (less than a day) to 3 (5–7 days). Items were summed to create depressive symptom scores. Internal consistencies in the current sample ranged from α = .74 (age 2) to α = .77 (ages 3 and 4). Prior research indicates that the CES-D is equally reliable for ethnic minority populations as for White Americans (Roberts, 1980). The CES-D has also been found to adequately distinguish between patient and clinical populations (Radloff, 1977). From ages 2–4, respectively, 45%, 38%, and 32% of mothers exceeded the CES-D’s cutoff of 16 for clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms.

Dyadic Coercive Interactions

At ages 2, 3, and 4, the videotaped interaction tasks involving the child and the primary caregiver were coded using the Relationship Affect Coding System (RACS; Peterson, Winter, Jabson, & Dishion, 2008). The RACS records three continuous streams of behavior—verbal, physical, and affect—and captures the duration of events within each. Verbal codes comprise positive, neutral, and negative talk and include verbal behavior change codes, such as positive structuring, neutral, and negative directives. Physical behaviors (e.g., hugging, handing each other objects) are coded as positive, neutral, and negative. Affect codes include anger, disgust, distress, ignoring, validation, and positive affect. The “off” codes of no talk, no physical contact, and neutral affect are used when verbal, physical behavior, or affect streams are not observed. The RACS coding was carried out using Noldus Observer (Noldus Information Technology, 2003), which enables continuous coding of an interaction as the behaviors are observed. As such, the exact durations and frequencies of the behaviors of interest are captured.

In this study, dyadic coercion (i.e., mutually coercive behaviors between the caregiver and the child) was defined as either parent or child being negatively engaged or directive, and the other member of the dyad responding by not talking, ignoring, being negatively engaged, or directive (for full details about variable construction, see Sitnick et al., 2015). We calculated the total duration each parent–child dyad was observed in dyadic coercion and divided that time by the overall session time to get a duration proportion score. Reliability coefficients were in the “good” to “excellent” range with overall Kappa scores at each age of .93.

Child CP

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for ages 1.5–5 is a 99-item questionnaire for assessing behavioral problems in young children (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). PC and SC completed the CBCL at each home assessment. These items are scored on a 3-point scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). For the purposes of the current study, the broadband externalizing factor was used at ages 2, 3, and 4 (PC scales M α = 0.78; SC scales M α = 0.80). The sample had scores much higher than normative averages (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000), especially according to PC reports: At age 2, 19% had “subclinical” levels of externalizing problems (T scores = 60–63) and 31% of children had “clinical” levels of externalizing problems (T scores > 63). The CBCL has previously been demonstrated to have high test–retest reliability (e.g., α = 87 for the externalizing factor and α = 90 for the internalizing factor) and high criterion-related validity, as demonstrated by its ability to differentiate between clinically referred and nonreferred children (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

Child Internalizing

The CBCL broadband internalizing factor at child ages 2, 3, and 4 was used to determine whether transactional relationships between maternal depression and parent–child coercion are specific to child CP, rather than reflecting a more generalized effect on child psychopathology. According to PC reports, 19% of children had subclinical levels of internalizing problems at age 2; 16% of children had clinical levels of internalizing problems.

Data Analysis Plan

Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2004) was utilized to conduct the structural equation modeling for these analyses. Percentage of missing data ranged across indicators and time with a mean of 14.1%. Because of power considerations, the missing data were treated as ignorable (missing at random), and a variant of maximum likelihood estimation was used that allowed for the total sample of 650 to be analyzed. To account for missing data and positive skew of some indicators, we used the maximum likelihood-robust estimator in Mplus. To evaluate the fit of the structural models, several fit indices were used, including the chi-square goodness of fit statistic, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), all of which have been typically used as indices of practical fit.

A cross-lagged panel model with cross-domain paths among the three variables of interest was used to explore potential child and parent effects based on evidence for reciprocal relations between maternal depressive symptoms and parent–child coercion, parent–child coercion and child CP, and maternal depressive symptoms and child CP. All models included the autoregressive paths for each construct and within-time correlations of residual covariances among constructs. In addition, all models included the previously discussed covariates for each study. The model was repeated replacing child CP with child internalizing and computing separate models for PC and SC reports of child externalizing and internalizing.

RESULTS

Bivariate relations revealed relative stability within each domain over time (see Table 1). Mothers’ depressive symptoms at each year were positively and significantly correlated with one another (rs = .42 and .54, p < .001, from ages 2–3 and 3–4, respectively). Bivariate correlations across the parent–child coercion observation measure were similarly robust (rs = .31 and .24, p < .001, from ages 2–3 and 3–4, respectively). Auto-regressive correlations for both PC and SC reports of child CP were high over time (for PC reports rs = .60 and .69, p < .01, from ages 2–3 and 3–4, respectively; for SC reports rs = .43 and .44, p < .001, from ages 2–3 and 3–4). Correlations between child externalizing symptoms and internalizing symptoms were relatively high at each time point (rs = .52, .59, and .65 for PC report at ages 2, 3, and 4, respectively, and rs = .69, .70, and .69 for SC report).

TABLE 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Vriables Used in Models for Child Externalizing and Internalizing

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Depression (Age 2) | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Maternal Depression (Age 3) | .42** | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Maternal Depression (Age 4) | .40** | .54** | — | |||||||||||||||

| 4. P-C Coercion (Age 2) | .04 | .12* | .07 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 5. P-C Coercion (Age 3) | .01 | .07 | .06 | .31** | — | |||||||||||||

| 6. P-C Coercion (Age 4) | .04 | .12** | .10* | .33** | .24** | — | ||||||||||||

| 7. PC-Reported Child Externalizing (Age 2) | .16** | .93** | .15** | .07 | .03 | .00 | — | |||||||||||

| 8. PC-Reported Child Externalizing (Age 3) | .25** | .40** | .32** | .13** | .12** | .10* | .60** | — | ||||||||||

| 9. PC-Reported Child Externalizing (Age 4) | .20** | .32** | .36** | .10* | .08 | .12** | .49** | .59** | — | |||||||||

| 10. SC-Reported Child Externalizing (Age 2) | .06 | .14** | .07 | .09 | .05 | .03 | .31** | .29 | .28** | — | ||||||||

| 11. SC-Reported Child Externalizing (Age 3) | .15** | .24** | .15** | .07 | .12* | .07 | .31** | .45** | .35** | .43** | — | |||||||

| 12. SC-Reported Child Externalizing (Age 4) | .08 | .18** | .14** | .06 | .15** | .09 | .28** | .41** | .43** | .39** | .44** | — | ||||||

| 13. PC-Reported Child Internalizing (Age 2) | .26** | .27** | .18** | .23** | .13** | .10* | .50** | .37** | .31** | .23** | .25** | .20** | — | |||||

| 14. PC-Reported Child Internalizing (Age 3) | .28** | .41** | .32** | .24** | .15** | .15** | .34** | .58** | .45** | .17** | .31** | .24** | .54** | — | ||||

| 15. PC-Reported Child Internalizing (Age 4) | .21** | .34** | .38** | .17** | .10* | .12** | .27** | .42** | .63** | .16** | .26** | .20** | .54** | .66** | — | |||

| 16. SC-Reported Child Internalizing (Age 2) | .08 | .15** | .07 | .21** | .01 | .10 | .10* | .12* | .10 | .63** | .28** | .16** | .30** | .24** | .19** | — | ||

| 17. SC-Reported Child Internalizing (Age 3) | .11* | .17** | .13** | .18** | .14** | .10 | .12* | .24** | .15** | .33** | .68** | .20** | .35** | .38** | .31** | .50** | — | |

| 18. SC-Reported Child Internalizing (Age 4) | .13* | .20** | .16** | .21** | .16** | .12* | .12* | .22** | .26** | .25** | .28** | .59** | .28** | .32** | .30** | .33** | .34** | — |

| M | 16.75 | 15.39 | 14.99 | .11 | .09 | .09 | 59.49 | 56.00 | 53.65 | 53.40 | 51.43 | 49.90 | 56.33 | 54.33 | 53.31 | 52.82 | 52.05 | 50.36 |

| SD | 10.66 | 10.95 | 10.85 | .08 | .06 | .05 | 8.21 | 9.94 | 10.49 | 9.56 | 9.95 | 10.07 | 8.53 | 9.57 | 10.08 | 10.51 | 10.44 | 10.26 |

Note. T scores are provided in presenting descriptive statistics for the CBCL Externalizing, although raw scores were used for testing hypotheses. P-C = parent-child; PC = primary caregiver; SC = secondary caregiver

p < .05.

p < .01.

There were several significant associations found between covariates and primary study variables. Although not a focus of the study, we identified one consistent intervention effect. Consistent with a previous article (Shaw, Connell, Dishion, Wilson, & Gardner, 2009), assignment to the FCU intervention significantly predicted fewer maternal depressive symptoms at age 3 (β = −.09, p < .01) and lower levels of child CP at age 4 (β = −.06, p < .05). Assignment to the FCU was not associated with lower levels of dyadic coercion at ages 3 or 4. This finding is consistent with prior studies using the current study cohort (Smith et al., 2014), although Sitnick and colleagues (2015) found that the FCU influences dyadic coercion at age 5 by increasing positive engagement at ages 3 and 4. In addition, Hispanic children had mothers with lower levels of depressive symptoms at age 2 (β = −.08, p < .05), higher levels of parent–child coercion at ages 2 and 3 (β = .22, p < .01 and β = .13, p < .05, respectively), and lower levels of PC-reported child CP at ages 2 and 3 (β = −.12, p < .01 and β = −.10, p < .01, respectively). African American children had higher levels of parent–child coercion at ages 2 and 3 (β = .18, p < .01 and β = .11, p < .05, respectively). Finally, being female was a significant predictor of lower levels of child CP at age 3 (β = −.06, p < .05, respectively). Not graduating from high school was associated with higher levels of mothers’ depressive symptoms at age 2 (β = .12, p < .01), higher levels of parent–child coercion at age 2 (β = .16, p < .01), and higher levels of child externalizing at child ages 2 and 3 (β = .13, p < .01 and β = .08, p < .05, respectively).

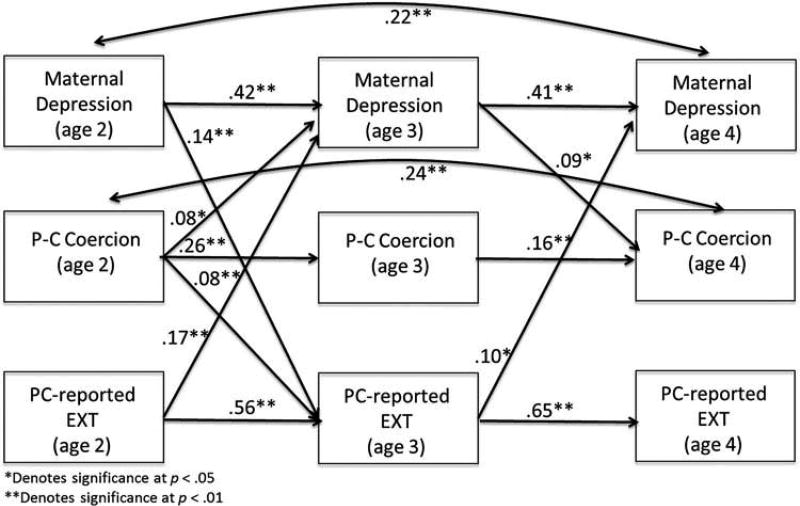

Transactional Relationship Between Maternal Depression, Parent–Child Coercion, and PC-Reported Child CP

The model included paths from maternal depression to parent–child coercion, parent–child coercion to child CP, and maternal depression to child CP. Based on modification indices, we added two second-order autoregressive paths—one for maternal depressive symptoms from 2 to 4, and one for parent–child coercion from 2 to 4. That these paths were significant and resulted in an improved model fit (χ2dif = 63.11, p < .001) is indication that baseline levels of maternal depression and parent–child coercion at age 2 have delayed causal effects on the same variables at age 4. The final structural model for the analyses using PC-reported CP is presented in Figure 1. Fit statistics indicated an acceptable fit to the data, χ2(9) = 26.18, p < .05, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .01.

FIGURE 1.

Transactional effects between maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and primary caregiver reported child CP. Only significant pathways are shown for visual simplicity (including concurrent correlations). Standardized beta weights are shown. P-C Coercion = Parent-Child Coercion, PC Reported Ext. CBCL = Primary Caregiver Reported Externalizing subscale from the Child Behavior Checklist. Covariates: child gender, child race/ethnicity, intervention status, geographic site, and mothers’ education level.

Transactional relations between maternal depression and child CP were evident over time, with significant positive contributions of child CP at age 2 to maternal depression at age 3 (β = .17, p < .01) and of child CP at age 3 to maternal depression at 4 (β = .10, p < .01). Likewise, maternal depression at age 2 was positively related to child CP at age 3 (β = .14, p < .01). Effect sizes, as indicated by standardized beta coefficients, are relatively small, as βs in the range of .10–.20 are generally considered to be small in magnitude (Ferguson, 2009). As Adachi and Willoughby (2015) suggested, to gain a better understanding of effect size it may be both helpful to compare the beta coefficients, which tend to be attenuated because of the model having accounted for longitudinal stability, relative to bivariate relations that do not account for auto-regressive or prior cross-lagged effects. Values for the bivariate correlations between maternal depression and child CP were generally much stronger than the standardized beta coefficients in the autoregressive model (e.g., r = .32 for the correlation between PC-reported externalizing at age 3 and maternal depression at age 4).

Transactional relations between maternal depression and parent–child coercion were modest. Higher levels of parent– child coercion at age 2 predicted higher levels of maternal depression at 3 (β = .08, p < .05), and maternal depression at 3 was positively associated with parent–child coercion at 4 (β = .09, p < .05). There was also a significant positive path from parent–child coercion at age 2 to child CP at age 3 (β = .08, p < .05).

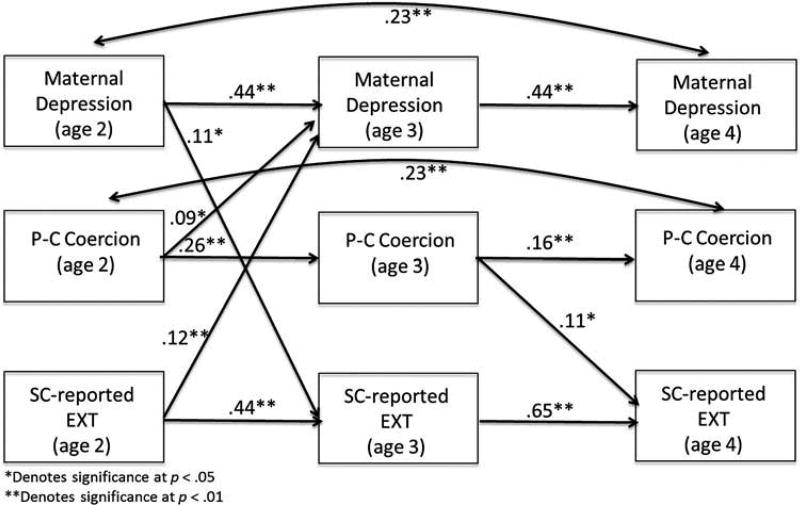

Transactional Relationship Between Maternal Depression, Parent–Child Coercion, and SC-Reported Child CP

All models were recomputed using SC report on child CP at ages 2, 3, and 4. The pattern of bivariate correlations between all study variables was similar to the model using PC reports of child CP. Fit statistics indicate that the model, presented in Figure 2, is a good fit to the data, χ2(9) = 13.44, p = .15, RMSEA = .03, CFI = .99, SRMR = .02. As in the model using PC report, there were significant paths from child CP at age 2 to maternal depression at age 3 (β = .12, p < .05) and from maternal depression at age 2 to child CP at age 3 (β = .11, p < .05), although these paths were weaker when SC report was used.

FIGURE 2.

Transactional effects between maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and secondary caregiver reported child CP. Only significant pathways are shown for visual simplicity (including concurrent correlations). Standardized beta weights are shown. P-C Coercion = Parent-Child Coercion, SC Reported Ext. CBCL = Secondary Caregiver Reported Externalizing subscale from the Child Behavior Checklist. Covariates: child gender, child race/ethnicity, intervention status, geographic site, and mothers’ education level.

Similar to the model using PC report of child externalizing, higher levels of parent–child coercion at age 2 predicted higher levels of maternal depression at age 3 (β = .09, p < .05), but unlike in the PC report model, maternal depression at age 3 was not associated with age 4 coercion (β = .08, ns). In addition, in contrast to the PC model, the pathway from coercion at age 2 to child CP at age 3 was not significant using SC report (β = .05, ns).

Last, there was limited evidence for transactional relations from parent–child coercion to child CP, with only one significant and positive path from age 3 coercion to SC-reported child CP at age 4 (β = .11, p < .05). This path was not significant in the PC-report model, though the same path from age 2 to 3 was significant.

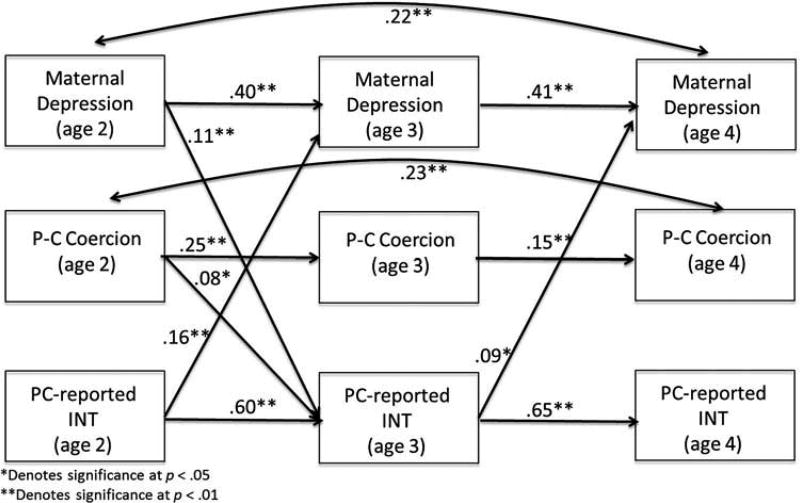

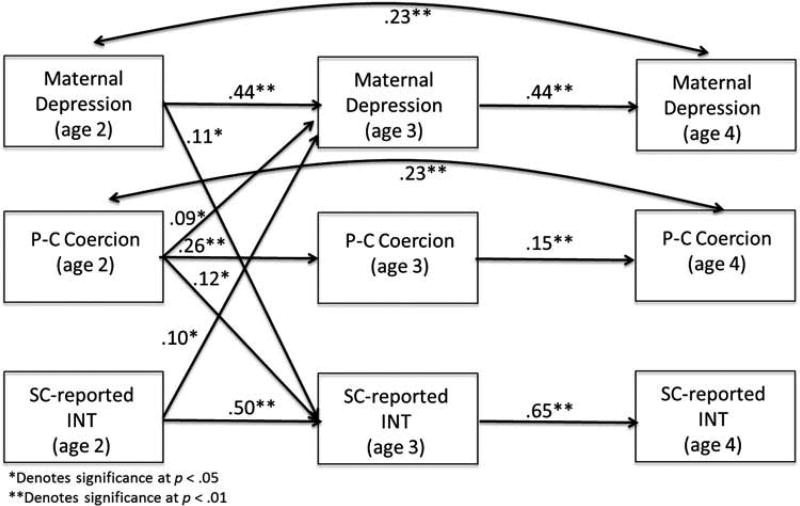

Transactional Relationship Between Maternal Depression, Parent–Child Coercion, and Child Internalizing

Although findings for models with child internalizing instead of child CP were generally similar, there were a few important differences. For the PC-report model with child internalizing, presented in Figure 3, most of the fit indices, with the exception of RMSEA, indicated an adequate fit for the data, χ2(9) = 73.30, p < .05, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .96, SRMR = .03. Compared to the model using child externalizing, in the child internalizing model, the pathway from age 2 parent–child coercion to age 3 maternal depression was no longer significant (β = .06, ns) and the pathway from age 3 depression to age 4 coercion was also no longer significant (β = .07, ns). For the SC-report model, presented in Figure 4, the fit indices indicated an acceptable fit for the data, χ2(9) = 16.99, p = .05, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .99, SRMR = .02. Compared to the child externalizing model using SC report, there were two pathways that differed: The path from age 2 coercion to age 3 SC-reported internalizing was significant (β = .12, p < .05), and the pathway from age 3 coercion to age 4 internalizing was not significant (β = .09, ns).

FIGURE 3.

Transactional effects between maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and primary caregiver reported child internalizing. Only significant pathways are shown for visual simplicity (including concurrent correlations). Standardized beta weights are shown. P-C Coercion = Parent-Child Coercion, PC Reported Int. CBCL = Primary Caregiver Reported Internalizing subscale from the Child Behavior Checklist. Covariates: child gender, child race/ethnicity, intervention status, geographic site, and mothers’ education level.

FIGURE 4.

Transactional effects between maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and secondary caregiver reported child internalizing. Only significant pathways are shown for visual simplicity (including concurrent correlations). Standardized beta weights are shown. P-C Coercion = Parent-Child Coercion, SC Reported Int. CBCL = Secondary Caregiver Reported Internalizing subscale from the Child Behavior Checklist. Covariates: child gender, child race/ethnicity, intervention status, geographic site, and mothers’ education level.

DISCUSSION

The current study sought to extend past research on transactional processes between maternal depression and early-emerging child CP by introducing parent–child coercion as a third variable to understand the interplay between maternal depression and child adjustment during early childhood. A series of models using ratings from multiple caregivers showed evidence for some transactional relationships between maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and child CP across three waves of data when children were 2, 3, and 4 years of age. Maternal depression and parent–child coercion at age 2 were both associated with higher rates of PC-reported child CP at age 3, and higher rates of CP at age 3 were subsequently associated with greater maternal depression at age 4. In addition, child CP and parent–child coercion at age 2 were both associated with higher rates of maternal depression at age 3, which was then associated with increases in parent–child coercion at age 4. Support for transactional associations were less consistent using SC report of child CP. In the models with child internalizing, findings were mostly replicated for associations leading to internalizing or internalizing predicting later outcomes, but in the model with PC-reported internalizing, associations between coercion and maternal depression were attenuated. Although effect sizes for significant cross-lagged paths were generally modest, explaining less than 10% of the variance in outcome, these estimates tend to be conservative indicators of cross-domain pathways as they account for autoregressive effects. Adachi and Willoughby (2015) suggested that traditional guidelines for interpreting the magnitude of effect size may not be applicable to autoregressive models and that, in certain situations (e.g., if bivariate correlations are stronger in magnitude), even very small effect sizes may be clinically meaningful. The present study offers methodological strengths, provides complementary evidence across informants of transactional associations between maternal depression and child CP, and explores parent–child coercion as a possible contributor to mother–child reciprocal effects.

Transactional Associations Between Maternal Depression and Child CP

Analyses exploring transactional associations between maternal depression and child behavior problems partially supported our hypothesis that high levels of maternal depressive symptoms would predict subsequent elevations in children’s’ CP and high levels of children’s CP would predict subsequent elevations in maternal depressive symptoms. Mothers’ ratings of child CP predicted mothers’ depressive symptoms from age 2–3 and from age 3–4, an effect that was also observed for SC ratings from age 2–3. According to both informants of child behavior, maternal depression at age 2 was linked to child CP at age 3. As hypothesized and consistent with other studies, we found cross-informant support for associations between mother and child symptoms, and additional evidence of a child evocative effect at two time points based solely on mother report. Although there is some evidence suggesting that mothers with depression provide negatively biased ratings of children’s behavior (Burt et al., 2005; Goodman et al., 2011), it is also possible that maternal depression contributes to more honest and realistic appraisals of children’s adjustment problems (Cummings & Davies, 1994). Mothers may have provided more accurate ratings of children’s behavior than SCs based on the greater amount of time spent with their child; therefore, their perceptions of children’s CP at ages 2 and 3 might have been sufficient to increase their own depressive symptoms the following year.

The data provided some support for our hypothesis that transactional patterns between maternal depression and child CP would be stronger from age 2–3 than from age 3–4. According to PC report, child CP was associated with later maternal depression at both time points. According to SC report, child CP was only associated with later maternal depression from age 2–3. In addition, the pathway from maternal depression to child CP was only significant from age 2–3, for both PC and SC report. These results confirm that child problem behavior during toddlerhood routinely exacerbates maternal depression (Gross et al., 2009). In terms of developmental timing, the findings also are consistent with theory and prior research indicating that toddlers are vulnerable for developing problem behavior in the context of maternal depression (Connell & Goodman, 2002; Cummings & Davies, 1994; Shaw, Bell, & Gilliom, 2000), particularly in the context of living in poverty (Shaw & Shelleby, 2014). We found that maternal depression at age 2 was associated with an increase in children’s CP at age 3 and that this increase in child CP was subsequently associated with an increase in maternal depressive symptoms at age 4.

Maternal Depression and Parent–Child Coercion

This investigation provides some support for the notion that maternal depression is a risk factor for the development of coercive family processes. Consistent with our hypothesis, higher levels of maternal depression at age 3 were associated with higher levels of dyadic coercion at age 4, but only for PC report. Parent–child coercion at age 2 was associated with increased maternal depression at age 3; increased maternal depression at age 3 was then linked to increased coercion at age 4. This pathway in particular is illustrative of the transactional model, specifically how different processes in development are dynamic and constantly influencing one another. Previous research with toddler and preschool-age children has found that depressed mothers are more frequently oriented toward coercion, retaliation, and revenge than are nondepressed mothers (Kochanska et al., 1989). Similarly, a meta-analysis of 46 observational studies showed a moderate association between maternal depression and parenting behavior in the domain of negative behavior, such that higher levels of maternal depression were positively associated with irritable, critical, and coercive elements of parenting (Lovejoy et al., 2000). In this meta-analysis, the mean correlation across studies between maternal depression and negative parenting behavior was r = .20, moderate in magnitude and larger than that found in the current study, although effect sizes are expected to be smaller in an autoregressive model that accounts for prior levels of maternal depression and coercive parenting. The current study provided novel evidence of the link between maternal depression and later parent–child coercion in the preschool period. The effect of parent–child coercion on subsequent maternal depression was only evident at age 2–3, perhaps because of the slightly higher levels of parent–child coercion observed at age 2.

Parent–Child Coercion and Child CP

Some aspects of the hypothesized model were not supported. It was initially hypothesized that parent–child coercion at one time point would be associated with increases in child CP at subsequent time points and that child CP would be related to increases in parent–child coercion, although less strongly. Parent–child coercion at age 2 was related to PC-rated child CP at age 3 (but not for SC report), and dyadic coercion at age 3 was related to SC-rated child CP at age 4 (but not for PC report). It is unclear why the patterns differed depending on the reporter. There was no evidence that child CP was associated with later increases in dyadic coercion in the current study.

Specificity of Transactional Model to Child CP

Repeating the models with child internalizing to test whether the effects were specific to child CP suggested that transactional effects were largely evident for both forms of child problem behaviors. Like child CP, internalizing symptoms at ages 2 and 3 were associated with subsequent increases in maternal depression at ages 3 and 4 in the PC-report model. However, “indirect” effects involving maternal depression and parent–child coercion became weaker in the model with child internalizing symptoms, suggesting that child internalizing problems are accounting for a significant portion of the variance in associations between maternal depression and parent–child coercion. This was surprising, as we expected that these pathways would be similar across both internalizing and externalizing models. One possible explanation is that child internalizing accounts for more of the variance in maternal depressive symptoms than child externalizing because of greater genetic risk between maternal depression and child internalizing than for child externalizing. Future studies on this topic are clearly warranted before drawing conclusions on this issue.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

Although the current results are promising, the findings must be tempered with an appreciation of the methodological limitations of the study. One limitation is that findings may not be generalizable beyond the current sample of ethnically diverse, low-income families with toddler-age children recruited from WIC clinics. Replication in other sociodemographic groups would help determine whether the current findings can be applied to more varied populations.

Second, the current study focused narrowly on maternal depression versus other aspects of children’s family context (e.g., marital quality, parental social support, paternal depression). Although we obtained data on paternal/other SC depression, because of changing parental structures over time, data on the same SC’s depression were available for only a subset of families, and even a smaller percentage with biological or residential fathers. In general, few studies have explored how depression in fathers or other parental figures might relate to parenting and child adjustment. Even less is known about father–child interactions of depressed fathers (Compas, Howell, Phares, Williams, & Ledoux, 1989; Kane & Garber, 2004; Ramchandani et al., 2013). However, some preliminary results from the current sample indicate that SC depression at child age 3 is positively associated with mother–child coercion at age 4 (Reuben & Shaw, 2015).

The results of the current study have important clinical implications regarding the origins of early child problem behavior and the prevention and treatment of depression in mothers with young children. First, because both maternal depression and child CP are highly stable across time beginning in the toddler period, it suggests the need for early screening and prevention practices (Shaw et al., 2009), especially for those families living in poverty. In fact, previous reports using the same data set indicate that the FCU is associated with improvements in positive parenting, maternal depression, and child CP from ages 2–4 (Dishion et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2009) and through middle childhood (Dishion et al., 2014; Shaw et al., 2015). In addition, Reuben, Shaw, Brennan, Dishion, and Wilson (2015) found that such improvements in maternal depressive symptoms during the toddler period were linked to both parents’ and teacher reports of improvements in child emotional symptoms at school-age. Although the current study’s finding of an intervention effect on maternal depressive symptoms is consistent with such prior research, direct effects of the intervention were not identified for children’s CP or for parent– child coercion at specific ages. In prior studies examining FCU intervention effects on children’s CP, we have focused on the decreasing slope of CP over time rather than at one assessment point (Dishion et al., 2008, 2014).

Second, the evidence for transactional influences between maternal depression and parent–child coercion suggests an etiological link, and such reciprocal processes may require specific family-centered treatments (Dishion & Stormshak, 2007; Gross, Shaw, & Moilanen, 2008). Certainly, there is strong reason to believe that the development of early child problem behavior may be entrenched in family relationships (Shaw et al., 2009). Furthermore, pathways from maternal depression to parent– child coercion during early childhood implicate the importance of maternal psychological symptoms that may interfere with parenting processes. Interventions that target maternal depression might improve parent–child interactions and/or child CP, both of which one would expect to have some positive collateral effects on maternal depression (Ammerman et al., 2011; Reuben et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2009).

Clinical Significance

Although the effect sizes for the significant paths in the current study were relatively small in magnitude, the use of autoregressive models still suggests the findings might have clinical significance (Adachi & Willoughby, 2015). As expected, there was greater evidence for transactional associations between ages 2 and 3 than from 3 to 4. This may indicate that age 2 is a particularly important time to intervene, as changing levels of parent–child coercion at age 3 may not be effective for reducing either maternal depression of child externalizing at subsequent ages. The current study’s findings that transactional relationships between maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and child externalizing and internalizing behavior problems are strongest during early toddlerhood make a strong case for continued development of early intervention and the importance of screening at-risk families for available interventions as early as possible.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite these important caveats, the current study extends our understanding of transactional processes among maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and child CP in early childhood. Independent and reciprocal effects between maternal depressive symptoms and child CP were evident across reporters. In addition, parent–child coercion was found to be an outcome of maternal depression in one of the models, providing some support for a link between interpersonal stress and the generation of depression. The results confirm prior research on the independent contributions of maternal depression and child CP to the maintenance of both problem behaviors and suggest the need to account for family’s interpersonal exchanges when designing and implementing interventions to address child CP in low-income populations.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants MH50907 (National Institute of Mental Health) and DA25630 (National Institute on Drug Abuse) to the third author and grants DA22773 and DA16110 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to the third, fourth, and fifth authors. This article was also supported by a Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1247842) from the National Science Foundation to the second author.

Contributor Information

Katherine A. Hails, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Julia D. Reuben, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Daniel S. Shaw, Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh

Thomas J. Dishion, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University

Melvin N. Wilson, Department of Psychology, University of Virginia

References

- Achenbach T, Rescorla L. Manual for the ASEBA preschool scales and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi P, Willoughby T. Interpreting effect sizes when controlling for stability effects in longitudinal autoregressive models: Implications for psychological science. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2015;12(1):116–128. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2014.963549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar B, Sroufe L, Egeland B, Carlson E. Distinguishing the early-onset/persistent and adolescence-onset antisocial behavior types: From birth to 16 years. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(2):109–132. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400002017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman RT, Putnam FW, Stevens J, Bosse NR, Short JA, Bodley AL, Van Ginkel JB. An open trial of in-home CBT for depressed mothers in home visitation. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15(8):1333–1341. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0691-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Eyberg SM. Father involvement in parent training: When does it matter? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:599–605. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3204_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Pettit JW, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Effect of maternal depression on child behavior: A sensitive period? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75(2):81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne WM, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Pardini DA, Loeber R. Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(5):679–692. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt KB, Van Dulmen MH, Carlivati J, Egeland B, Alan Sroufe L, Forman DR, Carlson EA. Mediating links between maternal depression and offspring psychopathology: The importance of independent data. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:490–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Brownell CA, Hungerford A, Spieker SI, Mohan R, Blessing JS. The course of maternal depressive symptoms and maternal sensitivity as predictors of attachment security at 36 months. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(2):231–252. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404044499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12(3):467–488. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400003114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron A, Weiss B, Harris V, Catron T. Parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology: Specificity, task dependency, and interactive relations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35(1):34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe DE, Shaw DS, Brennan LM, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Inhibitory control as a mediator of bidirectional effects between early oppositional behavior and maternal depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26(4, Pt. 1):1129–1147. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung EK, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Lee HJ, Culhane JF. Maternal depressive symptoms and infant health practices among low-income women. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e523–e529. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.e523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civic D, Holt VL. Maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior problems in a nationally representative normal birthweight sample. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2000;4:215–221. doi: 10.1023/A:1026667720478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Howell DC, Phares V, Williams RA, Ledoux N. Parent and child stress and symptoms: An integrative analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25(4):550–559. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.4.550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Goodman SH. The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:746–773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994;35:73–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2005;46:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DA, Burgers DE, Rabinowitz J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 2015;141(4):858–900. doi: 10.1037/a0038498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Thomas SA, Goodman KL, Kundey SM. Principles underlying the use of multiple informants’ reports. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:123–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Shaw DS, Connell AM, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: Preventing problem behavior by increasing parents’ positive behavior support in early childhood. Child Development. 2008;79:1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Brennan LM, Shaw DS, McEachern AD, Wilson MN, Jo B. Prevention of problem behavior through annual family check-ups in early childhood: Intervention effects from home to early elementary school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42(3):343–354. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9768-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, Stormshak EA. Intervening in children’s lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptive processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Reiser M. Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: Longitudinal relations to quality of children’s social functioning. Child Development. 1999;70:513–534. doi: 10.1111/cdev.1999.70.issue-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH, Curtis LJ. Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Melotti R, Heron J, Ramchandani P, Wiles N, Murray L, Stein A. The timing of maternal depressive symptoms and child cognitive development: A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:632–640. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.2012.53.issue-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, Kavanagh K. Parenting during the second year: Effects of children’s age, sex, and attachment classification. Child Development. 1993;64:258–271. doi: 10.2307/1131450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40(5):532–538. doi: 10.1037/a0015808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21(3):245–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00917534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske U, Shear MK, Anderson B, Cyranowski J, Strassburger M, Matty M, Frank E. Comparison of severe life stress in depressed mothers and non-mothers: Do children matter? Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:109–117. doi: 10.1002/da.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Healy B, Goldstein S, Perry S, Bendell D, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Infants of depressed mothers show “depressed” behavior even with nondepressed adults. Child development. 1988;59:1569–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DM, Teti DM. The effects of maternal depression on children. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:329–353. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(90)90065-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(1):1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbos T, Granic I. Changes in maternal depression are associated with MST outcomes for adolescents with co-occurring externalizing and internalizing problems. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:1415–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Burwell RA, Nagin DS. Transactional processes in child disruptive behavior and maternal depression: A longitudinal study from early childhood to adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(1):139–156. doi: 10.1017/s0954579409000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL. Reciprocal associations between boys’ externalizing problems and mothers’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:693–709. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9224-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Reciprocal models of child behavior and depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers in a sample of children at risk for early conduct problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:742–751. doi: 10.1037/a0013514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LA, Williams CA, Greenberg RS. Supports, stressors, and depressive symptoms in low-income mothers of young children. American Journal of Public Health. 1985;75:518–522. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.75.5.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Life events and depression: The plot thickens. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:179–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00940835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:1065–1082. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanington L, Ramchandani P, Stein A. Parental depression and child temperament: Assessing child to parent effects in a longitudinal population study. Infant Behavior & Development. 2010;33(1):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw DS. The development of coercive family processes: The interaction between aversive toddler behavior and parenting factors. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. Boston, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kuczynski L, Maguire M. Impact of diagnosed depression and self-reported mood on mothers’ control strategies: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1989;17(5):493–511. doi: 10.1007/BF00916509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros CD, Garber J. Dynamic associations between maternal depressive symptoms and adolescents’ depressive and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:1069–1081. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9433-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Viding E, Rijsdijk FV, Plomin R. Relationships between parental negativity and childhood antisocial behavior over time: A bidirectional effects model in a longitudinal genetically informative design. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(5):633–645. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K, Wolfe R, Lyubchik A, Steingard R. Depressive symptoms in parents of children under age 3: Sociodemographic predictors, current correlates, and associated parenting behaviors. In: Halfon N, McLearn KT, Schuster MA, editors. Child Rearing in America: Challenges Facing Parents with Young Children. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 217–259. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand JF, Hock E, Widaman K. Mutual relations between mothers’ depressive symptoms and hostile-controlling behavior and young children’s externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:335–353. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR020401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan JD, Kotelchuck M, Cho H. Prevalence, persistence, and correlates of depressive symptoms in a national sample of mothers of toddlers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1316–1323. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, Cooper P. The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Development. 1996;67:2512–2526. doi: 10.2307/1131637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide: statistical analysis with latent variables: User’ss guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Noldus Information Technology. The Observer Reference Manual 5.0. Wageningen, the Netherlands: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Moffitt TE, Broadbent JM, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Caspi A. Female and male antisocial trajectories: From childhood origins to adult outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20(2):673–716. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary SG, Slep AM, Reid MJ. A longitudinal study of mothers’ overreactive discipline and toddlers’ externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27(5):331–341. doi: 10.1023/A:1021919716586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Vol. 3. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. The early development of coercive family process. In: Reid JB, Patterson GR, Snyder J, editors. Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercion theory: The study of change. In: Dishion TJ, Snyder JJ, editors. The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics. 2016. p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Vol. 4. Eugene, OR: Castalia; New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J, Winter C, Jabson J, Dishion TJ. Coding manual. Eugene: Child and Family Center, University of Oregon; 2008. The relationship affect coding system. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Arsiwalla DD. Commentary on special section on “bidirectional parent-child relationships”: The continuing evolution of dynamic, transactional models of parenting and youth behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(5):711–718. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani PG, Domoney J, Sethna V, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, Murray L. Do early father–infant interactions predict the onset of externalising behaviours in young children?. Findings from a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2013;54:56–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Marcuse F, Oberlander SE, Papas MA, McNary SW, Hurley KM, Black MM. Stability of maternal depressive symptoms among urban, low-income, African American adolescent mothers. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;122:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben JD, Shaw DS. Parental depression and the development of coercion in early childhood. In: Dishion TJ, Snyder J, editors. The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics. London, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Reuben JD, Shaw DS, Brennan LM, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. A family-based intervention for improving children’s emotional problems through effects on maternal depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(6):1142–1148. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research. 1980;2(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A. The transactional model. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Leve LD. Clarifying parent-child reciprocities during early childhood: The early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:89–107. doi: 10.1023/B:CCFP.0000030287.13160.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp D, Hay DF, Pawlby S, Schmücker G, Allen H, Kumar R. The impact of postnatal depression on boys’ intellectual development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:1315–1336. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.1995.36.issue-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21(5):493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ, Gilliom M. A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:155–172. doi: 10.1023/A:1009599208790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Connell A, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of intervention effects on early childhood problem behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(2):417–439. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Keenan K, Vondra J. Developmental precursors of externalizing behavior: Ages 1 to 3. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:355–364. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.30.3.355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Shelleby EC. Early-starting conduct problems: Intersection of conduct problems and poverty. Annual Review of Clinicial Psychology. 2014;10:503–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Sitnick SL, Brennan LM, Choe DE, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Gardner F. The long-term effectiveness of the Family Check-Up on school-age conduct problems: Moderation by neighborhood deprivation. Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28:1471–1471. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Winslow EB, Owens EB, Vondra JI, Cohn JF, Bell RQ. The development of early externalizing problems among children from low-income families: A transformational perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26(2):95–107. doi: 10.1023/A:1022665704584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitnick SL, Shaw DS, Gill A, Dishion T, Winter C, Waller R, Wilson M. Parenting and the family check-up: Changes in observed parent–child interaction following early childhood intervention. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(6):970–984. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.940623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]