Abstract

Background

Little is known about adult-onset atopic dermatitis (AD).

Objectives

To determine the associations and clinical characteristics of adult-onset AD.

Methods

A prospective study of 356 adults with AD (age ≥18 years) was performed using standardized questionnaires and examination. AD severity was assessed using Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), Scoring AD (ScorAD), body surface area (BSA), numeric rating scale (NRS)-itch and sleeplessness. Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to determine dominant clinical phenotypes. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the relationship between adult-onset AD and distinct phenotypes.

Results

149 (41.9%) reported onset of AD during adulthood, with 87 (24.4%) after age 50 years. Adult- vs. childhood-onset AD was associated with birthplace outside the US (chi-square, P=0.0008), but not sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking or alcohol consumption (P≥0.11); and decreased personal history of asthma, hay fever and food allergy and family history of asthma and food allergy (P≤0.0001 for all). There was no significant difference of EASI, SCORAD, BSA, NRS-itch, NRS-sleep or POEM between adult vs. childhood-onset AD (Mann-Whitney U test, P≥0.10). LCA identified 3 classes: 1. high probability of flexural dermatitis and xerosis with intermediate to high probabilities of head, neck and hand dermatitis; 2. high probability of flexural dermatitis and xerosis, but low probabilities of head, neck, and hand dermatitis; 3 lower probability of flexural dermatitis, but highest probabilities of virtually all other signs and symptoms. Adult-onset AD was significantly associated with class 1 (multivariate logistic regression; aOR [95% CI]: 5.54 [1.59–19.28]) and 3 (14.03 [2.33–85.50]).

Conclusions

Self-reported adult-onset is common and has distinct phenotypes with lesional predilection for the hands and/or head/neck.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, eczema, adult onset, asthma, hay fever, atopic history, severity

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin disorder that commonly affects both children and adults. Most clinical and epidemiological research has focused on childhood AD, but few have studied AD in adults 1. Recent studies suggest that AD may be more common in adults than previously recognized, with 1-year US prevalence ranging from 3–10% 2, 3. The higher than expected prevalence of AD may be attributed to high rates of persistent childhood disease and/or adult-onset disease. One longitudinal study found that 80% of children have persistence of AD symptoms into adulthood, with only 50% achieving a period of disease clearance by age 20 years 4. However, a recent meta-analysis of 44 studies suggested that 50% and 80% of children with AD achieved a period of observed clear skin by 3 and 8 years of follow-up, respectively 5. Thus, persistence of childhood AD is likely not the only factor contributing to adult AD. Over the past decade, several studies have reported substantial proportions of adults with AD having disease onset in adulthood (≥18 years of age), i.e. adult-onset AD 6–12. We hypothesized that adults with AD have high rates of adult-onset of disease.

Previous studies found that foreign born American children had significantly lower rates of AD than those born in the US; however, odds of AD increased with US residence for >10 years 13. Similarly, foreign born American adults had significantly lower rates of asthma than those born in the US; the odds of asthma also increased with US residence for >10 years 14. These results suggest that foreign-born Americans may have later onset of AD and atopic disease. We hypothesized that adults born outside the US have higher rates of adult-onset AD.

Still, little is known about the phenotypical differences between childhood and adult-onset AD. Recent studies showed an important role of barrier disruption in childhood AD and the atopic march in the development of atopic disease 15. We hypothesized that adults with adult-onset AD has lower rates of atopic disease than those with long-standing AD and associated barrier disruption since childhood. Moreover, we hypothesized that adult-onset AD may present with different clinical characteristics than childhood disease. The present study sought to determine the proportion of adult AD with adult-onset, risk factors and phenotypical differences of adult-onset AD.

Methods

Study design

We performed a prospective dermatology practice-based study to determine the predictors of adult onset AD. Self-administered questionnaires were completed by adult (≥18 years) patients of the eczema clinic prior to their encounter. Surveys included questions about socio-demographics, birthplace and age of moving to the US for those born outside the US. Patients were then evaluated with a medical history and skin examination by a dermatologist (JS). Surveys were administered between January, 2014 and June, 2016. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Northwestern University and informed consent was waived.

Assessment of AD

AD was assessed using the Hanifin and Rajka major and minor criteria 16. Specific elements presented in this analysis, include the major criteria - pruritus, distribution of eczematous lesions, personal or family history of AD, asthma or hay fever, and minor criteria – xerosis, ichthyosis, palmar hyperlinearity, keratosis pilaris, age of AD onset, nipple dermatitis, cheilitis, Dennie-Morgan infraorbital folds, facial pallor/erythema, conjunctivitis and eyelid dermatitis, pityriasis alba, dermatitis of the anterior neck folds, history of cutaneous infections, clinical course worsened by environmental or emotional factors, pruritus when sweating. AD severity was assessed using the numeric rating scale (NRS) for itch and sleeplessness, body surface area (BSA) of involved skin, Scoring AD (SCORAD) and Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI).

Data Processing and Statistical Methods

All data analyses and statistical processes were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare age of AD onset (<18 vs. ≥18 years) with birthplace in the US (binary), continent of birth (North America, Canada, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa), whether AD preceded migration, personal history of asthma, hay fever, food and medication allergy (binary), family history of AD, asthma, hay fever, food or medication allergy (binary), distribution of eczematous lesions and other signs and symptoms of AD (all binary). Median (interquartile range [IQR]) were determined for the number of combined signs and symptoms, EASI, SCORAD, BSA, NRS-itch and NRS-pruritus. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare these outcomes between adult- vs. child-onset groups. A 2-sided P-value ≤0.01 was taken to indicate statistical significance for all hypothesis tests.

Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to examine phenotypical patterns of binary variables of 19 signs and symptoms of AD. LCA uses observed categorical or binary data to identify patterns, termed latent classes. Subjects with similar response patterns are categorized into specific classes. Conditional probabilities were estimated using maximum likelihood to characterize the latent classes by indicating the chance that a member would give a certain response (yes or no) for the specific item. Conditional probability plots are presented, where probabilities closer to 0 or 1 indicate lower or higher chances, respectively. LCA regression models examine the differential effects of individual variables across unobserved classes. The ideal number of latent classes and best fitting models were selected by minimizing the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Consistent Akaike information criterion (CAIC) statistics and interpretability. Multivariate logistic regression was then performed to determine the association between adult-onset AD and membership in the latent classes. Gender, race/ethnicity, BSA and EASI were included as covariates to address potential confounding. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated.

Sample size calculation

A priori sample size calculations were performed based on two co-primary analyses: the association between adult onset AD and 1. foreign birthplace and 2. personal history of asthma or hay fever. For the association with foreign birthplace, the referent and test groups were predicted to be 13% and 26% based on the proportion of foreign born adults in the US population17 and an expected doubling of the proportion in adult-onset AD. For the association with personal history of asthma, the referent and test groups were predicted to be 50% and 25% based on previously observed prevalences in adults with AD18 and an expected halving of that proportion in adult onset AD. A total of 308 and 123 adults were needed based on the Chi-square test, assuming 90% power with the use of 2-sided tests and an alpha level of 0.01 for each outcome19.

Results

Patient characteristics

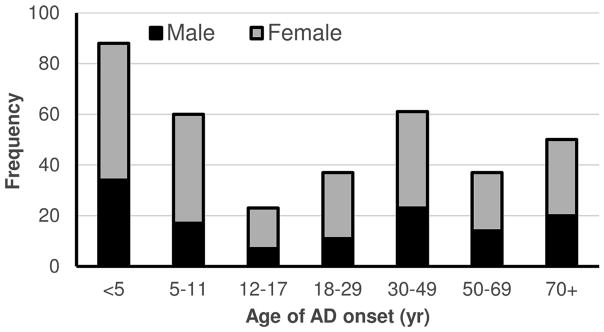

Overall, 356 adults (ages 18–93 years) were included in the study, including 230 women (64.6%) and 228 whites (64.0%). The mean ± std. dev. age at enrollment was 42.8 ± 16.7 years and age of self-reported AD onset was 30.5 ± 31.7 years. Two hundred and seven (58.1%) reported onset of AD during childhood and adolescence, with 88 (24.7%) before age 5 years and 87 (24.4%) after age 50 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of age of AD=onset among adults with AD.

Among patients with adult-onset AD, skin biopsies were performed in 66 (44.3%); 65 showed a pattern of spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils and none were consistent with cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Patch testing was performed in 82 (55.0%); 56 were negative and 11 showed at least one irrelevant positive reaction. Fifteen showed at least one relevant positive reaction. However, strict avoidance of the observed allergens only resulted in partial mitigation of their underlying skin disease, with all patients having ongoing chronic AD. Skin prick testing results were available for 38 and 14 patients with childhood- and adult-onset AD, with high rates of at least one positive allergen (single positive to aeroallergen: 7 [18.4%] and 2 [14.3]; multiple positives to aeroallergens: 28 [73.7%] and 11 [78.6%]; multiple positives to food allergens: 2 [5.3%] and 0 [0.0%]; negative: 1 [2.6%] and 1 [7.1%], respectively). Total serum immunoglobulin E levels were available for 11 and 6 patients with childhood- and adult-onset AD; 8 (72.7%) and 3 (50.0%) had levels ≥100 IU/ml with median (IQR) levels of 3,000 (1,240, 24,055) and 87.2 (30.0, 236.8) IU/ml, respectively. Forty nine patients were excluded from the study because they did not meet the Hanifin and Rajka criteria for AD (63.3%), were found to have an alternative diagnosis on skin biopsy (6.1%) or were found to allergic contact dermatitis that resolved with allergen avoidance (30.6%).

Patients with adult-onset AD were significantly more likely to be born outside the US compared to those with childhood onset AD (22.5% vs. 11.5%; chi square, P=0.008) (Table 1). Among foreign-born adults with childhood onset AD, 2 (14.3%) developed AD after migration to the US. Whereas, among adults with adult-onset AD, 27 (75.0%) developed AD after migration (P=0.0003). However, adult-onset AD was not associated with sex, race/ethnicity, current smoking or alcohol consumption (P≥0.11).

Table 1.

Association of gender and birthplace outside the US with adult onset atopic dermatitis.

| Variable | Age of AD onset$ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood (<18) (n=207) | Adulthood (≥18) (n=149) | ||

| Freq (%) | Freq (%) | P# | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 70 (33.8%) | 56 (37.6%) | 0.46 |

| Female | 137 (66.2%) | 93 (62.4%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 127 (61.4%) | 101 (67.8%) | 0.72* |

| Black | 30 (14.5%) | 15 (10.1%) | |

| Hispanic | 13 (6.3%) | 9 (6.0%) | |

| Asian | 34 (16.4%) | 22 (14.8%) | |

| Multiracial/Other | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Current cigarette smoker | |||

| No | 169 (88.0%) | 126 (91.3%) | 0.62 |

| Yes | 23 (12.0%) | 12 (8.7%) | |

| Current alcohol consumption | |||

| No | 67 (35.3%) | 37 (27.0%) | 0.11 |

| Yes | 123 (64.7%) | 100 (73.0%) | |

| Birthplace in US | |||

| Yes | 170 (88.5%) | 107 (77.5%) | 0.008 |

| No | 22 (11.5%) | 31 (22.5%) | |

| Continent of birth (outside US) | |||

| North America | 3 (13.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.057* |

| South America | 1 (4.6%) | 7 (22.6%) | |

| Europe | 7 (31.8%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

| Asia | 10 (45.5%) | 16 (51.6%) | |

| Africa | 1 (4.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Timing of migration | |||

| AD preceded migration | 20 (90.9%) | 9 (29.0%) | <0.0001* |

| AD developed after migration | 2 (9.1%) | 22 (71.0%) | |

Chi-square test was used for all tests unless where indicated.

Fisher-exact test

Column percentages are presented. Some frequencies may not sum to the total number of childhood and adult-onset cases due to missing values.

History of atopic disease

Adult-onset AD compared with childhood-onset AD was associated with a significantly decreased personal history of asthma (17.8% vs. 51.7%; P<0.0001), hay fever (37.7% vs. 58.7%; P=0.0001) and food allergy (15.4% vs. 43.9%; P<0.0001), but not medication allergy (30.5% vs. 32.5%; P=0.70) (Table 2). Moreover, adult-onset compared with childhood-onset AD was associated with a significantly decreased family history of AD (35.5% vs. 60.6%; P<0.0001), asthma (20.0% vs. 43.9%; P<0.0001), and food allergy (10.4% vs. 25.0%; P=0.0009), but not hay fever (23.9% vs. 36.2%; P=0.017) or medication allergy (9.0% vs. 14.8%; P=0.12).

Table 2.

Differences of atopic history, signs and symptoms of atopic dermatitis between child and adult-onset of disease.

| Sign | Missing values | Age of AD onset$ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood (<18) (n=207) | Adulthood (≥18) (n=149) | |||

| Freq (%) | Freq (%) | P-value# | ||

| Personal history | ||||

| Asthma | 8 | 104 (51.7%) | 26 (17.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Hay fever | 9 | 118 (58.7%) | 55 (37.7%) | 0.0001 |

| Food allergy | 14 | 87 (43.9%) | 22 (15.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Medication allergy | 18 | 64 (32.5%) | 43 (30.5%) | 0.70 |

| Family history | ||||

| Atopic dermatitis | 17 | 120 (60.6%) | 50 (35.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Asthma | 20 | 86 (43.9%) | 28 (20.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Hay fever | 21 | 71 (36.2%) | 33 (23.9%) | 0.017 |

| Food allergy | 33 | 47 (25.0%) | 14 (10.4%) | 0.0009 |

| Medication allergy | 33 | 28 (14.8%) | 12 (9.0%) | 0.12 |

| Physical signs | ||||

| Flexural dermatitis | 22 | 149 (76.4%) | 92 (66.2%) | 0.04 |

| Anterior neck fold dermatitis | 18 | 122 (61.0%) | 52 (37.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Facial dermatitis | 18 | 118 (59.0%) | 42 (30.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Conjunctivitis or eyelid dermatitis | 18 | 111 (55.5%) | 36 (26.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Dennie-Morgan fold | 18 | 75 (37.5%) | 16 (11.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Cheilitis | 18 | 79 (39.5%) | 17 (12.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Hand or foot dermatitis | 22 | 134 (68.7%) | 63 (45.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Nipple dermatitis | 22 | 29 (14.9%) | 7 (5.0%) | 0.004 |

| Xerosis | 16 | 162 (81.0%) | 113 (80.7%) | 0.95 |

| Pityriasis alba | 26 | 23 (12.0%) | 3 (2.2%) | 0.0007* |

| Palmar hyperlinearity/ichthyosis/keratosis pilaris | 22 | 121 (62.1%) | 45 (32.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Scalp | 18 | 96 (48.0%) | 35 (25.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Posterior auricular | 18 | 83 (41.5%) | 23 (16.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Nummular lesions | 29 | 12 (6.4%) | 21 (15.0%) | 0.0097 |

| White dermatographism | 24 | 8 (4.1%) | 6 (4.3%) | 0.94 |

| Follicular eczema | 21 | 11 (5.6%) | 7 (5.0%) | 0.82 |

| Anterior subcapsular cataracts | 17 | 6 (3.0%) | 8 (5.8%) | 0.21 |

| Keratoconus | 17 | 3 (1.5%) | 1 (0.7%) | 0.65* |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Clinical course worsened by environmental or emotional factors | 17 | 182 (91.9%) | 116 (82.3%) | 0.008 |

| Pruritus when sweating | 20 | 138 (70.1%) | 90 (64.7%) | 0.31 |

| Tendency toward cutaneous infections | 0 | 64 (30.9%) | 28 (18.85) | 0.0099 |

Chi-square test was used for all tests unless where indicated.

Fisher exact test

Column percentages are presented. Some frequencies may not sum to the total number of childhood and adult-onset cases due to missing values.

Signs and symptoms of AD

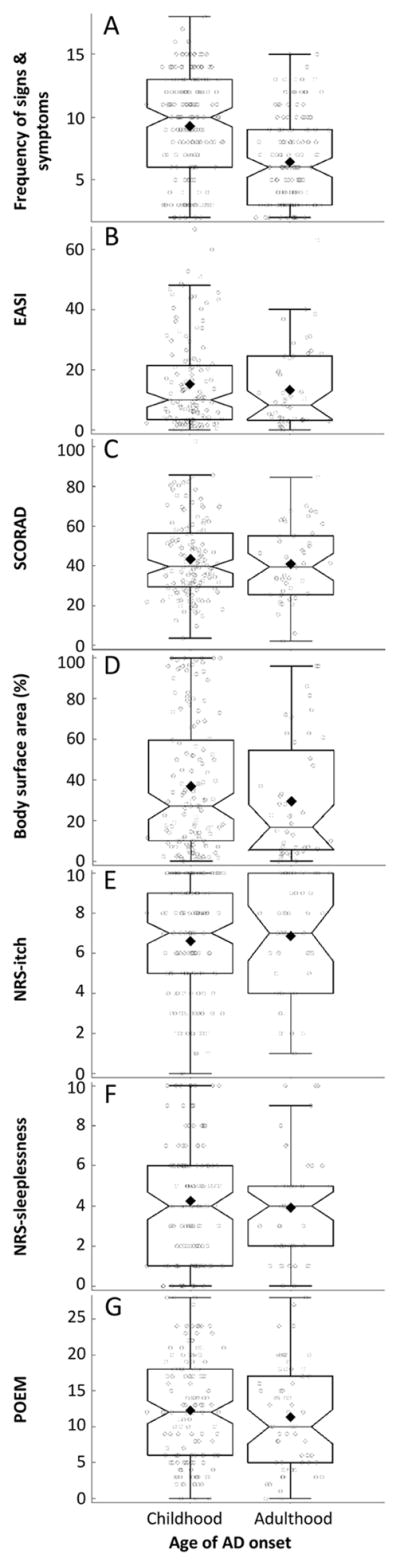

Adult-onset compared with childhood-onset AD was associated with significantly higher rates of nummular eczema lesions, but lower rates of 11 of 18 signs and symptoms of AD, including dermatitis affecting anterior neck fold; scalp; face; eyelids and conjunctivitis; Dennie-Morgan folds; hands or feet; or nipples; cheilitis; pityriasis alba; keratosis pilaris or palmar hyperlinearity or ichthyosis; clinical course worsened by emotional or environmental factors, or pruritus when sweating and tendency toward cutaneous infections (Table 3). However, there were no significant differences of dermatitis affecting the flexural areas, xerosis, white dermatographism, follicular eczema, anterior subcapsular cataracts and keratoconus. Further, patients with adult vs childhood-onset AD had a significantly lower number of combined AD signs and symptoms (median [IQR]: 6 [2, 8] vs. 10 [6, 13], P<0.0001) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Associations between adult- vs. childhood-onset AD with signs, symptoms and severity of disease.

Box-whisker plots and overlaid jitter plots of (A) frequency of AD signs and symptoms, (B) EASI, (C) SCORAD, (D) BSA, (E) NRS-itch, (F) NRS-sleepiness, and (G) POEM.

AD severity

There were no significant differences of disease severity between adult-onset and childhood-onset AD as judged by EASI (median [IQR]: 8.3 [2.8, 24.1] vs. 10.0 [2.8, 14.8]; Mann-Whitney U test, P=0.44) (Figure 2B), SCORAD (39.5 [23.0, 52.6] vs. 39.7 [27.4, 55.4]; P=0.56) (Figure 2C), and BSA (16.8 [6.0, 54.9] vs. 27.0 [9.4, 58.9]; P=0.10) (Figure 2D). However, there were no differences of NRS-itch (7 [4, 10] vs. 7 [5, 9]; P=0.60) (Figure 2E), NRS-sleep (4 [2, 5] vs. 4 [1, 6]; P=0.51) (Figure 2F) or patient-reported AD activity (POEM: 10 [5, 17] vs. 12 [6, 18]; P=0.43) (Figure 2G).

Latent class analysis of the adult-onset AD phenotype

LCA was used to identify phenotypical patterns associated with adult-onset AD. The best-fit model had three classes based on minimal BIC, CAIC and interpretability. Conditional probabilities of having different physical signs and symptoms in each class are plotted in Figure 3. Class 1 had high probabilities of flexural dermatitis and xerosis with intermediate to high probabilities of head, neck and hand dermatitis. Class 2 had high probability of flexural dermatitis and xerosis, but low probabilities of head, neck, and hand dermatitis. Class 3 had a lower probability of flexural dermatitis, but highest probabilities of virtually all other signs and symptoms. Adult-onset AD was significantly associated with Class 1 (multivariate logistic regression; aOR [95% CI]: 5.54 [1.59–19.28]) and 3 (14.03 [2.33–84.50]). That is, adult-onset AD was more likely to present with a phenotype consisting of lower probability of flexural dermatitis (class 3) and/or higher probability of hand and/or head and neck dermatitis (classes 1 and 3).

Figure 3.

Latent class analysis (LCA) was performed to determine the dominant patterns of signs and symptoms in adults with AD. LCA identified 3 classes: 1. high probability of xerosis and intermediate probabilities of flexural or hand dermatitis; 2. high probability of xerosis, flexural, head, neck and hand dermatitis; 3. highest probabilities of all signs and symptoms.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that adult-onset AD is associated with a distinct phenotype compared with child-onset AD, including less frequent personal and/or family history of atopic disease, fewer signs and symptoms of AD, with a higher probability of lesions affecting the head/neck and hands and lower probability of flexural lesions. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing more nummular eczema lesions, less flexural involvement and lesional predilection for the hands and face in adult-onset AD 7, 20. However, we found significantly lower rates of scalp and posterior auricular lesions and no differences for rates of follicular eczema. This is contrast with a previous study that found higher rates of both scalp and posterior auricular involvement and follicular eczema 7. Despite the observed phenotypical differences, we found no significant differences of AD severity, patient-reported intensity of itch or sleeplessness, disease activity (POEM) or pruritus when sweating. Thus, adult-onset and childhood-onset AD appear to have similar severity, symptomatology and quality of life impairment, despite the observed phenotypical differences. It is important for clinicians to account for the different phenotypes of adult-onset AD when evaluating and managing adult patients with dermatitis.

There are several practical points from this study for the management of adult AD. First and foremost, clinicians must recognize that the presentation of adult AD is more heterogeneous and may have different phenotypes. It is of course important to rule out other entities in the differential diagnosis, e.g. allergic contact dermatitis and cutaneous T cell lymphoma. However, the clinician can comfortably make the diagnosis of AD if the clinical presentation is consistent with AD and the appropriate workup for other etiologies is negative. Second, the lesional predilection for the head/neck and hands may require site-specific targeted treatment with either low-potency topical corticosteroids or non-steroidal topical agents for the head/neck area, and super-potent topical corticosteroids for the hands. Third, the similar rates of xerosis between childhood and adult-onset AD suggests that moisturizers and other barrier repair therapies are warranted in both patient subsets. Fourth, given the low rates of history and manifestations of atopic disease, skin-prick and RAST testing may not be warranted in the routine workup of most patients with adult-onset AD. Whereas, these may be useful in a subset of adults with childhood-onset AD, and those with comorbid asthma and rhino-conjunctivitis. On the other hand, it may be that uncontrolled AD in adulthood may predispose to eventual higher rates of adult-onset atopic disease. This is analogous to the “atopic march” observed in a subset of childhood AD 21. Thus, improved long-term control of the skin disease may offer an opportunity to mitigate or prevent adult-onset atopic disease. Finally, it is unknown if the distinct phenotypes observed in this study are associated with different prognosis or treatment response. A recent meta-analysis found that children with already persistent, later onset and/or more severe AD had increased persistence22. Adult-onset AD may similarly be associated with increased persistence and thus warrant long-term treatment regimens. Yet, it is unknown whether specific clinical interventions may prevent childhood AD from becoming adult AD. Future long-term studies are needed to elucidate these points.

The results of this study confirm our hypothesis adults with AD have high rates of adult-onset of disease. Adult-onset AD may be more common than commonly recognized and may affect almost half of adult cases. A US population-based telephone survey of 60,000 households similarly found that 54% of respondents with self-reported AD reported their disease onset in adulthood 6. Studies from Turkey, Singapore, Australia, Italy, Nigeria and China also reported substantial proportions (range of 9% to 88.0%) of AD patients had onset after 18 years of age 7–12. Of course, some of these patients may have in fact had childhood disease but were unaware of or have forgotten it. Regardless of whether such cases are adult onset per se or adult recurrence, there appears to be a larger subset of patients with activation of their skin disease in adulthood than previously recognized.

The present study confirms our hypothesis that that foreign-born patients were more likely to have adult-onset AD compared with those born in the US. We previously demonstrated that foreign-born American children had significantly lower rates of AD and atopic disease than those born in the US 23. However, the odds of AD significantly increased in foreign-born children after residing in the US for 10 or more years 23. Together, it appears that foreign-born Americans are at risk for later-onset AD, particularly in adulthood.

We found no significant sex-associations with adult-onset AD or with the associated phenotypes involving the hands and/or head/neck. In contrast, the US prevalence of adult AD was associated with female sex3 and one study showing a male preponderance of adult-onset AD 7. The complex relationship between sex, skin care practices, occupational exposures and the pathogenesis of AD require further study. We observed high rates of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption in this cohort overall, consistent with previous reports of increased smoking in children and adults and alcohol consumption in adults with AD 24, 25. However, there were no associations between adult-onset AD per se and current smoking status or alcohol consumption. This is in contrast with a case-control study of 225 Taiwanese adults that found that early and/or current exposure to cigarette smoking was associated with adult-onset disease 26. However, that study compared adult-onset AD to non-AD controls and those findings may have been attributable to AD, in general, and not adult-onset AD, in particular.

The mechanisms of adult-onset AD remain unclear. Perhaps the biggest question is whether such cases are truly adult-onset vs. adult-recurrence of AD. It is possible that adults presenting with new-onset disease including the full spectrum of AD signs and symptoms and comorbid allergic disease are actually adult recurrent disease. Whereas, adults presenting with prominent head/neck and hand/foot involvement and lower rates of allergic disease may truly be adult-onset AD. Alternatively, it is possible that even adult-recurrent disease is more likely to present with prominent head/neck and hand/foot involvement. Either way, it is mysterious that patients should have decades or a lifetime of clear skin and subsequently develop full-blown AD. Presumably, any genetic predisposition toward AD would have been programmed from birth. A study of 241 patients with AD found that the 4 most common FLG loss-of-function mutations were only associated with early childhood-onset AD (≤2 or 2–8 years), but not late-childhood (8–17 years) or adult-onset disease (≥18 years) 27. This suggests that there are different genetic and/or environmental determinants of adult-onset AD, which warrant further study. Future studies are warranted that compare the genetics and transcriptome of childhood vs. adult-onset AD.

This study has several strengths, including being prospective, standardized assessment of AD signs, as well as pruritus, sleeplessness, disease activity and severity using multiple validated instruments. In addition, alternative diagnoses in the differential diagnosis were ruled out using skin biopsy and/or patch testing when indicated. LCA was used to identify the dominant phenotypes of adult AD, and was able to detect 3 unobservable subgroups of patients, including those with lesional predilection for the hands/feet and/or head/neck. However, the study has limitations. In particular, the study was performed in an academic dermatologic setting and may not be generalizable to milder cases of AD or the entire US population.

In conclusion, adults with AD have high rates of self-reported adult-onset, lower prevalence of personal or family history of atopic disease, and distinct phenotypes with less flexural lesions and more involvement of the hands and/or head/neck, and nummular lesions. Future longitudinal studies are underway to determine whether these phenotypes are associated with different prognosis or treatment response.

What is already known about this topic?

The risk factors and clinical characteristics of adult-onset atopic dermatitis are poorly understood.

What does this article add to our knowledge?

Adults with AD have high rates of self-reported adult-onset, lower prevalence of personal or family history of atopic disease, and distinct phenotypes with less flexural lesions and more involvement of the hands and/or head/neck.

How does this study impact current management guidelines?

Clinicians caring for patients with AD should recognize the phenotypes associated with adult-onset AD. Further studies are needed to determine whether these phenotypes are associated with different treatment outcomes.

Acknowledgments

JI Silverberg had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: JI Silverberg

Acquisition of Data: JI Silverberg, P Vakharia, R Chopra, R Sacotte, N Patel, S Immaneni, T White, R Kantor, D Hsu

Analysis and interpretation of data: JI Silverberg, P Vakharia, R Chopra, R Sacotte, N Patel, S Immaneni, T White, R Kantor, D Hsu

Drafting of the manuscript: JI Silverberg

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JI Silverberg, P Vakharia, R Chopra, R Sacotte, N Patel, S Immaneni, T White, R Kantor, D Hsu

Statistical analysis: JI Silverberg

Administrative technical or material support: None

Study supervision: None

Financial disclosures: None

Funding Support: This publication was made possible with support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), grant number K12 HS023011, and the Dermatology Foundation.

REDCap is supported at FSM by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science (NUCATS) Institute, Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- EASI

Eczema Area and Severity Index

- SCORAD

Scoring Atopic Dermatitis

- POEM

Patient Oriented Eczema Measure

- NRS

Numeric Rating Scale

- LCA

latent class analysis

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- 95% CI

95% confidence interval

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Funding/Sponsor was involved? No

Design and conduct of the study: Yes__ No_X_

Collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data: Yes__ No_X_

Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript: Yes__ No_X_

Decision to submit the manuscript for publication: Yes__ No_X_

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Williams HC. Epidemiology of human atopic dermatitis--seven areas of notable progress and seven areas of notable ignorance. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:3–9. e1–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2012.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverberg JI, Garg N, Paller AS, Fishbein A, Zee PC. Sleep Disturbances in Adults with Eczema are Associated with Impaired Overall Health: A US Population-Based Study. J Invest Dermatol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margolis JS, Abuabara K, Bilker W, Hoffstad O, Margolis DJ. Persistence of mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:593–600. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.10271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JP, Chao LX, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI. Persistence of atopic dermatitis (AD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:681–7. e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanifin JM, Reed ML, Eczema P, Impact Working G. A population-based survey of eczema prevalence in the United States. Dermatitis. 2007;18:82–91. doi: 10.2310/6620.2007.06034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozkaya E. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:579–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nnoruka EN. Current epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in south-eastern Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:739–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandstrom Falk MH, Faergemann J. Atopic dermatitis in adults: does it disappear with age? Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:135–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tay YK, Khoo BP, Goh CL. The profile of atopic dermatitis in a tertiary dermatology outpatient clinic in Singapore. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:689–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu P, Zhao Y, Mu ZL, Lu QJ, Zhang L, Yao X, et al. Clinical Features of Adult/Adolescent Atopic Dermatitis and Chinese Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:757–62. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.178960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pesce G, Marcon A, Carosso A, Antonicelli L, Cazzoletti L, Ferrari M, et al. Adult eczema in Italy: prevalence and associations with environmental factors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1180–7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverberg JI, Joks R, Durkin HG. Allergic disease is associated with epilepsy in childhood: a US population-based study. Allergy. 2014;69:95–103. doi: 10.1111/all.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverberg JI, Durkin HG, Joks R. Association between birthplace, prevalence, and age of asthma onset in adults: a United States population-based study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:410–7. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Benedetto A, Kubo A, Beck LA. Skin barrier disruption: a requirement for allergen sensitization? J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:949–63. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanifin J, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1980;92:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.American FactFinder. US Census Bureau; Available from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_13_5YR_S0501&prodType=table. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Eckert L, Wu R, Ardeleanu M, Graham NM, et al. Patient burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD): Insights from a phase 2b clinical trial of dupilumab in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:491–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:116–28. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bannister MJ, Freeman S. Adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:225–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2000.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:S118–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim A, Silverberg JI. A systematic review of vigorous physical activity in eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:660–2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Durkin HG, Joks R. Prevalence of allergic disease in foreign-born American children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:554–60. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantor R, Kim A, Thyssen J, Silverberg JI. Association of atopic dermatitis with smoking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverberg JI, Greenland P. Eczema and cardiovascular risk factors in two US adult population studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.023. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CH, Chuang HY, Hong CH, Huang SK, Chang YC, Ko YC, et al. Lifetime exposure to cigarette smoking and the development of adult-onset atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:483–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rupnik H, Rijavec M, Korosec P. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are not associated with atopic dermatitis that develops in late childhood or adulthood. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:455–61. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]