Abstract

The complex nature of marine biodiversity is partially responsible for the lack of studies in Indian ascidian species, which often target a small number of novel biomolecules. We performed untargeted metabolomics using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) in two invasive ascidian species to investigate the inter-specific chemical diversity of Phallusia nigra and P. arabica in search of drug-like properties and metabolic pathways. The chemical profiling of individual ascidian species was obtained using GC–MS, and the metabolites were determined by searching in NIST library and literature data. The principal component analysis of GC–MS mass spectral variables showed a clear discrimination of these two ascidian species based on the chemical composition and taxonomy. The metabolites, lipids, macrolides, and steroids contributed strongly to the discrimination of these two species. Results of this study confirmed that GC–MS-based chemical profiling could be utilized as a tool for chemotaxonomic classification of ascidian species. The extract of P. nigra showed promising anti-tumor activity against HT29 colon cancer 35 µM and MCF7-breast cancer (34.76 µM) cells compared to P. arabica. Of the more than 70 metabolites measured, 18 metabolites that mapped various pathways linked to three metabolic pathways being impacted and altered in steroid biosynthesis, primary bile acid biosynthesis, and steroid hormone biosynthesis were observed to have changed significantly (p > 0.004, FDR < 0.01). Also, higher expression of this pathway was associated with more significant cytotoxicity in breast and colon carcinoma cells.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1273-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ascidian, Biomolecules, Cancer, Cytotoxicity, GC–MS, Multivariate statistical analysis

Introduction

The marine environment is a vast pool for new metabolites, often with unique structures and novel chemical classes, which are excellent candidates for development as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, agrochemical substances and molecular probes (Davidson 1993; Palanisamy et al. 2017a, b). Ascidians or tunicates are utilized as seafood because of the higher amount of proteins and micronutrients. Therefore, it is vital to study their active biomolecules and pharmacological properties when looking at their food applications. Most of the ascidian species are not edible seafood, but some solitary tunicates from the family Styelidae and Pyuridae are widely harvested, and cultured species used for human consumption. Ascidians are sessile marine organisms with the great ability to synthesize active biomolecules with potential therapeutic applications. So far only a few Indian marine ascidians were investigated chemically over the years as a potential source of natural products. Overall, the chemical diversity of Indian ascidians is least studied. It is essential to investigate the chemical defense of ascidian metabolites between predators and prey, which also makes a significant impact in the field of drug discovery.

The novel anticancer drug, ecteinascidin 743 (Yondelis®), was isolated from Ecteinascidia turbinata marketed by PharmaMar and approved by the European Commission and FDA for the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas and ovarian cancer. Another significant anti-tumor drug, plitidepsin (Aplidin®), isolated from Mediterranean ascidian Aplidium albicans, is in clinical usage for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Several other ascidian MNPs are at various stages of clinical trials, biotechnological and industrial applications (Molinski et al. 2009). The compound, lamellarin α 20-sulfate, isolated from the unidentified Indian ascidian, showed potential inhibition of anti-HIV activity against HIV-1 protease (IC50 16 µM) (Reddy et al. 1999). Also, tiruchanduramine, a β-carboline guanidine alkaloid, isolated from ascidian Synoicum macroglossum collected in Tiruchandur coast, India, exhibited moderate α-glucosidase inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 78.2 µg/mL (Ravinder et al. 2005).

Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC–MS) are the prominent techniques to examine the chemical diversity of both plants and animals. Metabolomics is applied for drug analysis, disease diagnosis and species discrimination. These methods are widely used to identify functional chemical groups and classify the metabolites distribution (Vetter 2011). GC–MS-based metabolomics method can quickly obtain comprehensive information about endogenous metabolites in biological samples (Hu et al. 2017). Till date, few reports have depicted the metabolite profiling of marine ascidians using mass spectral variables (Palanisamy et al. 2017a), species specificity of symbiosis and secondary metabolites of ascidians (Tianero et al. 2015). The previous studies (Tianero et al. 2015; Palanisamy et al. 2017a) showed that the diverse chemical diversity of marine ascidians and their significance difference of metabolites was due to different habitat changes and species-specific secondary metabolites, which are thought to serve a defensive role and have been applied to drug discovery (Palanisamy et al. 2017a).

Steroid biomolecules are a class of prevalent natural products from marine organisms. They also have a potential to be used for cancer therapies. The first generation of cardiac glycoside-based anticancer drugs are currently in clinical trials (Molinski et al. 2009; Palanisamy et al. 2017a, b). Ferraldeschi et al. (2013) have reported the enzymes involved in molecular pathways inhibiting steroid biosynthesis in prostate cancer and breast cancer. Cancer is the second most threatening killer disease after cardiac disease in India. Referring to World Health Organization world cancer report 2015, the Indian Society for Clinical Research has reported 0.7 million new cancer cases to emerge every year in the country, killing over 0.35 million people and expected to rise in the next 10 years. This makes it is essential to concentrate on new and more efficient cancer therapeutics in addition to the prevention and diagnostic prospects.

In this study, we aimed to metabolic profiling of Indian ascidian Phallusia arabica and P. nigra using untargeted GC–MS combined with multivariate statistical analysis and screening their crude compounds against three tumor cell lines HeLa (cervical cancer), HT29 (colon cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer cells) using MTT bioassay to find anti-tumor activity of Phallusia spp. To further investigate the relationship of candidate biomarkers to breast and colon carcinoma cell proliferation, we attempt to identify potential biomarkers in ascidians and identified involving the most relevant metabolic pathways.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

MeOH—methanol, CHCl3—chloroform, CH2Cl2—dichloromethane, Na2SO4—sodium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) were used for the crude extraction and successive partition of the aqueous phase. KBr—potassium bromide, MTT-3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide, isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich) were utilized for FTIR analysis and MTT bioassay.

Sample collection and preparation of ascidian extracts

Both the invasive ascidian samples were collected in Tuticorin coastal waters, India, in the low tide depth range from 2 to 4 m depth. The collected ascidian species, Phallusia arabica (Savigny, 1819) and P. nigra (Savigny, 1819) were identified (Ali and Tamilselvi 2016) (Fig. S1 is given in Supporting information). Phallusia arabica (n = 5) and P. nigra (n = 5) has been extracted by MeOH/CHCl3 using soxhlet extraction method then re-suspended in MeOH to precipitate salt, filtered and afterwards diluted 7:3 with water (MeOH:H2O). A successive partition of the aqueous phase was performed, at first with CH2Cl2 (2:1, v/v, threefold) and then with Na2SO4 (Palanisamy et al. 2017a). The obtained extracts from both species were successively tested with anti-tumor activity against three cancer carcinoma cell lines.

GC/MS analysis

The FTIR spectra of both ascidian species were analyzed to differentiate the P. arabica and P. nigra based on the functional group of chemical components of crude extracts (Fig. S2). The MeOH extracts of both ascidians (replicate samples were analyzed) were acquired by a newly developed GC–MS method for analyzing their chemical composition by GC with MS Agilent Technologies GC 7890 C 240 ms Ion trap. The GC injector was set to 260 °C in split mode condition and the injector temperature was set initially 80 °C for 1 min with a 4°C/min ramping up to 300 °C and isotherm for 300 °C for 5 min. Capillary column CP8877 VF-35ms with 30 m × 250 µm × 0.25 µm was used. A continuous flow rate of 1 mL/min of carrier gas helium was used. The total run time was approximately 60 min. MS detection parameters were set to initial 3 min solvent delay followed by with full scan mode 99–1000 (m/z) with the collection of data from external ionization mode mass range of 10–1000 m/z with acquisition data type-centroid, ionization control Target TIC 20,000 counts, emission current 25 µA and trap temperature was set at 150 °C, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Metabolic profiles from the GC–MS analysis were converted into NetCDF file format and subsequently processed by the XCMS online (https://xcmsonline.scripps.edu) using default settings for peak finding and alignment. The resulting three-dimensional matrix containing peak index, sample name and normalized peak intensity was introduced into online bioinformatics tool Metaboanalyst (Version 3.0) which was used for multivariate statistical analysis. The normal distribution of mass spectral variables was checked and data were log10 transformed and mean centered. The multivariate statistical analysis model, principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). PCA model was used to develop models to discriminate ascidian samples according to their metabolites contribute to the separation. GC–MS spectral data were collected from every single sample; before analysis of PCA, data normalization was identified using descriptive analysis followed by log transformation and mean centered method (Hu et al. 2017; Satheeshkumar 2012) PLS-DA allowed the determination of discriminating ascidian metabolites using the variable importance of protection (VIP). The score value of VIP specified the contribution of a metabolite variable to the discrimination between all the studied samples. From a mathematical point of view, the scores of VIP are calculated for each variable as a weighted sum of squares of PLS weights. The mean of VIP values is 1, and usually, the VIP values higher than 1 is considered as significant (Xia and Wishart 2011). The higher VIP score is in agreement with a robust discriminatory ability and thus forms a criterion for the selection of biomarkers.

Identification of metabolites

The metabolic profiling of low molecular weight compounds was represented as the chromatographic peaks in total ion-current chromatograms (TICs). Peaks with intensity higher than threefold of the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio were recorded and integrated. Identification of these peaks was based on the mass spectral library NIST standard reference database. The relative metabolites identified with details of retention time, the molecular weight are given in Supporting information (Table S2).

Anti-tumor activity

The following cancer cell lines are screened against ascidian crude extracts HeLa-cervical cancer, HT29-colon cancer, MCF-7-breast cancer by MTT bioassay methods. The tumor cell lines used in this study were obtained from Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Rome, Italy.

Cell culture

Cancer cell lines HeLa-cervical cancer and MCF-7-breast cancer cells were cultured using DMEM medium and HT29-colon cancer by RPMI medium. Cells were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% air and 100% humidity. Various dose preparations: 20 mM stock solution prepared using DMSO from that different doses such as 1–50 µM was prepared (Palanisamy et al. 2017a). We have prepared the 20 mM concentration of extracts using hypothetical molecular weight (400). 1 mM = 1000 mmol from this stock solution we have generated micromolar concentration. 1000–3000 cells at 200 µL were seeded in 96-well plates (HeLa: 1000; HT-29: 2000; MCF-F: 3000 cells/200 µL). Cells treated with various concentrations from 1 to 50 µM were incubated for 72 h.

Cell viability

Cell viability was estimated by MTT assay, which evaluates the levels of mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity using 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma) reduction assay. Cell viability in treated vs untreated control cells was calculated for each concentration of drugs used as “OD of treated cells/OD of control cells” x 100 (Fernandes et al. 2011). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated using CalcuSyn software (version 2.0, BIOSOFT, Cambridge, UK). Significant differences between the mean of control vs various doses were tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons using GraphPad Prism 6, Demo Version, Windows 10, California. Statistically significant differences were assumed at p < 0.05 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Metabolomic pathway analysis

To unravel the chemical defense mechanism of ascidian metabolites, MetaboAnalyst (http://www.metaboanalyst.ca) was used for pathway prediction. Only the metabolites with available connectivity information in the KEGG database were included in the analysis. Connections supported at least two references in the literature are reported (Xia and Wishart 2016). Pathway analysis was performed using over-representation analysis method, hypergeometric test and selecting pathway topology relative centrality between centrality analysis methods. Network analysis of the identified biomarkers showed their interrelationships based on the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/compound/).

Results and discussion

Comparative analysis of ascidian metabolome

Metabolite profiling of flora and fauna has gained more widespread applications in identifying drug metabolites, establishing metabolite maps and lending clues mechanism of bioactivation (Palanisamy et al. 2017a; Koplovitz and McClintock 2011). However, the knowledge of the chemical diversity of various Indian ascidians is scarce. In total, 46 metabolite peaks containing between 234 and 860 m/z in P. arabica extract and 68 metabolite peaks containing between 170 and 870 m/z in P. nigra extract were reported. In this study, the maximum number of metabolites was reported from the invasive ascidian P. nigra compared to P. arabica. Significant metabolic differences were observed between the two species. Similar to this present study, Palanisamy et al. (2017a) have reported that invasive ascidian Styela plicata collected in Messina Coast is producing a higher level of fatty acid compounds compared to the Mediterranean native species Ascidia mentula. Lipid and lipid-like compounds 61.4% (e.g., cholestane steroids), fatty acids, terpenoids, macrolides (1.79%), and androstanes (0.2%) are the most dominant compounds in P. arabica. In P. nigra, lipid and lipid-like small molecules such as cholestane steroids (42%), ergostane steroids (10.19%), stigmastanes and derivatives (10.08%), macrolides (5.1%), isoprenoids (2.76%), androstanoids (2.51%), amides (0.5%), and indanes (0.4%) are prepotent. In the previous study, 18 metabolites were reported from P. nigra, the metabolite phthalic acid significantly inhibited aldose reduction activity and showed potential cytotoxicity against Type II diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (Ananthan and Selva Praphu 2014).

Among the identified metabolites, lipids, and steroids were most abundantly distributed in both ascidian crude extracts which represent the anti-microbial, anti-oxidant and anti-fouling properties. The sterol compounds, stigmasterol and campesterol had the therapeutic potential for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and showed potent cytotoxicity against colon carcinoma (HCT-116), and breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) (Odate and Pawlik 2007). Epoprostenol sodium has the property of anti-metastatic and inhibitor of platelet aggregation (Párraga et al. 2017). This is the first report of epoprostenol sodium compound from the ascidian species P. nigra.

Odate and Pawlik (2007) have reported the role of vanadium in the chemical defense of Caribbean ascidian P. nigra and confirmed that its blood was unpalatable to fish but palatable to bluehead wrasse Thalassoma bifasciatum but not inhibiting microbial growth. It is due to the presence of higher amount of tunic acidity in ascidians, which was noticed as a key feature for the non-palatability of ascidians by fish (Koplovitz and McClintock 2011). However, the mechanism of such defense is not very clear, suggesting further investigation of the underlying chemical diversity of ascidians in chemical defense. In a recent study, Pohnert (2005) have reported the polyunsaturated aldehydes and fatty acid contents were important in the interaction of marine organisms with their environment. Interestingly, Fernandes et al. (2011) have reported that metabolism of steroids (stigmasterol, or β-sitosterol) was involved in mollusc reproduction cycle, survival rates of juvenile and inhibition of the animal growth rate. The findings of the above study suggest that biosynthesis of fatty acids and steroids could be involved in non-indigenous ascidians reproduction cycle, their larval survival and settlements in new marine habitat, and competition with native organisms (Palanisamy et al. 2017a).

Further, Tamilselvi et al. (2015) have reported the bioaccumulation of heavy metals such as Cu, Cd, Pb and Hg from the Phallusia sp. and other ascidians collected from Tuticorin waters, India. The values of all the ascidians sampled in Tuticorin water were slightly higher than European Union (EU) and World Health Organization (WHO) acceptable limit. In this study, the paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) biotoxins were utterly absent in both ascidian species. Based on the above study, we are suggesting that ascidians collected in Tuticorin waters should not be utilized for human consumption. However, further studies on toxic heavy metal accumulation, microbial pathogens, essential amino acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids of these species are recommended for considering this solitary ascidian species as commercial seafood.

Principal component analysis

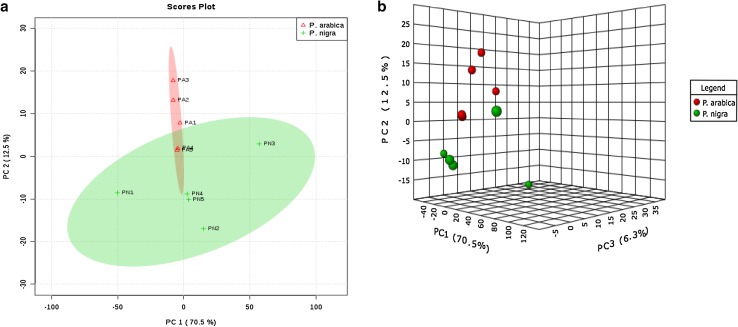

The GC–MS-based mass spectral variables, chemical groups and the taxonomic group were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA). The aim of this classification was to discriminate the invasive ascidian samples according to their metabolite composition and chemical groups. Three principal components accounting for 99% of the total variance are retained by the eigenvalue > 1 rule, loading of group 1 (PC1 72.2%) and group 2 (PC2 10.9%) is discriminating of two invasive Phallusia spp. based on the metabolites (Fig. 1). PC1 has distinctly discriminated P. nigra species from the ascidian P. arabica and plotted separately on the right side. In this study PC1, corresponding to the higher eigenvalue, and mostly correlated with peak maximum intention. Based on the results of PCA analysis, it can be concluded that fatty acids contribute the most significantly discriminate in the first discrimination function following macrolids, carotenoids and steroids. In PC2, invasive ascidian P. nigra was classified separately, the compounds indanes and benzenoids contributed more to discriminate this species from other species. Both the studied tunicates are invasive species in Indian waters; the specimen considered here cannot be confused with morphologically similar species from the genera Phallusia: P. arabica and P. nigra. Similar results of this present study, the metabolites of Egyptian soft corals were identified using MS/NMR-based metabolomics approach and discriminated their metabolites using orthogonal partial least square-discriminate analysis method (Farag et al. 2016). In a similar study, Choi et al. (2005) have classified the metabolites llex species and identified the significant metabolites contributed to the discrimination using multivariate statistical analysis and recommended this tool for chemotaxonomic studies. PCA analysis of GC–MS mass spectral variables could be utilized as a reliable tool for species discrimination of Phallusia spp. The outcome of this study concluded that PCA analysis of GC–MS mass spectral variables could be utilized as a reliable tool for species discrimination and taxonomic classification of marine ascidians (Palanisamy et al. 2017a).

Fig. 1.

The metabolic classification of two Phallusia spp. using PCA and 3D-PCA analysis of two invasive ascidians metabolite variables (a, b). PC1 and PC2 plots show distinctive discrimination of P. arabica and P. nigra species. PA: Phallusia arabica; PN: Phallusia nigra. Compounds (listed in Table S2) are represented by a number of visualization

Partial least square discriminant analysis

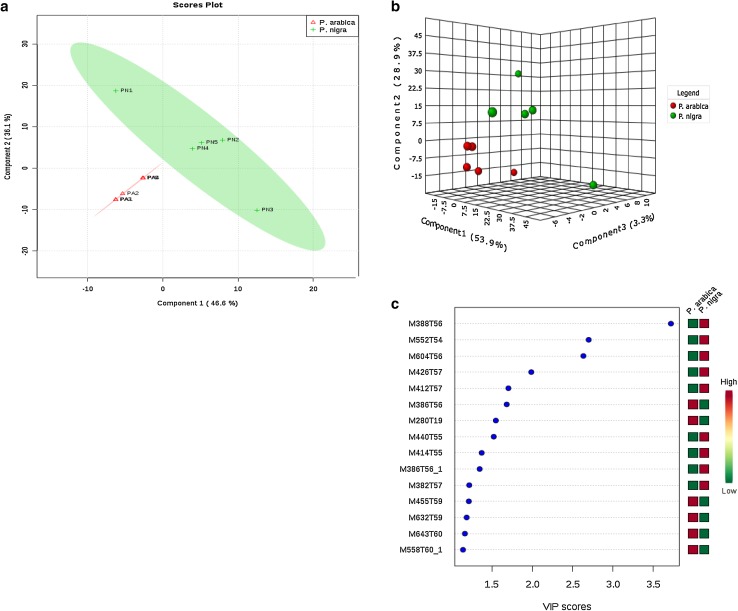

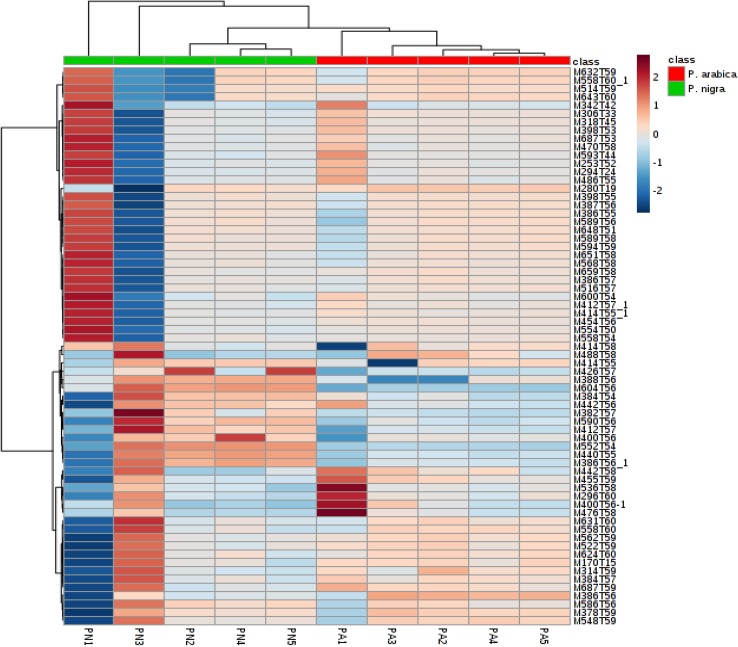

A partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and variable importance for projection (VIP) statistics were applied to understand the different metabolic pattern in two invasive ascidians better and to detect significant variable responsible for group separation in the model. The critical model parameters, R2 (R2X 0.917, R2Y 0.961) and Q2 (Q2X 0.823, Q2Y 0.919) in this model was larger than 0.5 suggesting that this statistical model was robust and had good fitness and prediction. Both the invasive ascidian species were clearly discriminated in the PLS-DA plot (Fig. 2). Variables were pre-selected as the potential candidate when their VIP values were larger than 1.0. The identified potential marker metabolites are listed in Table 1. A total of eight marker compounds with VIP value higher than 1.5 (Fig. 2c; Table 1) were identified using NIST standard reference database. In this study, the ascidian P. nigra strongly discriminating the other species P. arabica, six metabolites (i.e., cholestan-7-ol, lycoxanthin, milbemycin B, 29-methylisofucosterol, stigmasterol, ergosta-7,22-dien-3-ol) were significantly changed and up-regulated and cholestan-2-one were downregulated in Phallusia spp. Heatmap of the different ascidian metabolites with VIP values > 1 from the PLS-DA model is given in Fig. 3. Results presented in this study facilitated the envisioning of metabolites that contributed to discriminate between the two-ascidian species. Moreover, both invasive ascidian species belong to the same genus Phallusia and could have the similar biological synthesis of metabolites which is collected in the same study station. The chemical structure of the ascidian secondary metabolites is often species-specific; in this study, we classified two invasive Phallusia spp. by chemical diversity along with morphological characteristics. Results of this study are helpful to the taxonomist, natural products chemist and pharmaceutical industries to solve selected taxonomic issues and for drug discovery program.

Fig. 2.

PLS-DA and 3D PLS-DA score plots from the GC–MS analysis of two invasive ascidians (a, b). c The most contributing mass peaks with variable importance in projection (VIPs) score plot of 20 metabolite variables

Table 1.

List of differential metabolites for discrimination of two invasive ascidian species

| S. no. | Metabolites | RT mins | m/z | Molecular formula | VIP score | Fold change | p value | Group | CAS no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cholestan-7-ol | 56.36 | 388.68 | C27H48O | 3.71 | 8.96 | 0.03 | Lipids | 80-97-7 |

| 2 | Lycoxanthin | 54.84 | 552.87 | C40H56O | 2.69 | 10.07 | Carotenoids | 19891-74-8 | |

| 3 | Milbemycin B | 56.47 | 604.18 | C33H46ClNO7 | 2.63 | 5.81 | 0.01 | Macrolides | 107024-98-6 |

| 4 | 29-Methylisofucosterol | 57.05 | 426.72 | C30H50O | 1.98 | 7.15 | 0.09 | Steroids | 56362-45-9 |

| 5 | Stigmasterol | 57.33 | 412.69 | C29H48O | 1.7 | 6.64 | 0.09 | Steroids | 83-48-7 |

| 6 | Cholestan-2-one | 56.11 | 386.65 | C27H46O | 1.68 | − 2.48 | 0.09 | Steroids | 16020-93-2 |

| 7 | 5-Eicosene | 19.45 | 280.53 | C20H40 | 1.54 | 1.32 | Lipids | 74685-30-6 | |

| 8 | Ergosta-7,22-dien-3-ol | 55.86 | 440.71 | C30H48O2 | 1.52 | 5.47 | Steroids | 17472-78-5 | |

| 9 | 4-Cholesten-7α,12α-diol-3-one | 55.16 | 414.71 | C27H46O | 1.37 | 1.86 | 0.09 | Steroids | 1254-03-1 |

| 10 | Epicholestrol | 56.89 | 386.66 | C27H46O | 1.34 | 4.71 | Steroids | 474-77-1 |

Fig. 3.

Heatmap of the ascidian metabolites with variable importance in projection (VIP) values > 1 from the PLS-DA model

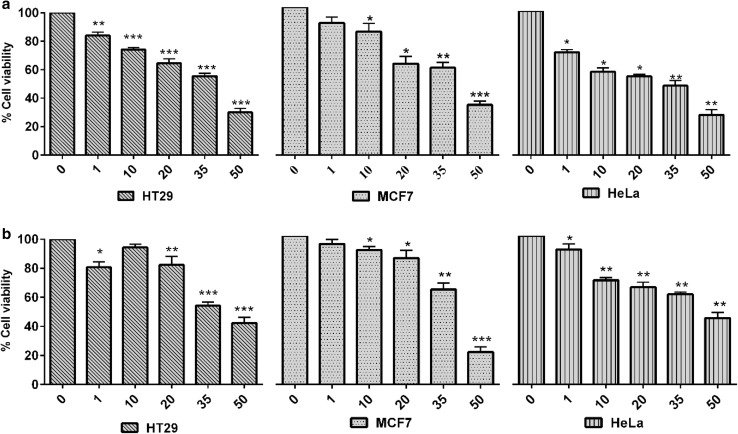

Anti-tumor activity of ascidian

Table 2 and Fig. 4 show the anti-tumor activity of Phallusia spp. against three tumor cell lines. The extracts of P. arabica showed potential anti-tumor activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines with IC50 values of 38.28 µM and exhibited modest growth inhibition against HeLa and HT29 cells with IC50 values of 42.52 and 43 µM, respectively. The crude extracts of P. nigra showed potential anti-tumor activity against HT29 colon cancer cell lines (IC50 35 µM) and modest growth inhibition against HeLa and MCF-7 with IC50 values of 39.72 and 34.76 µM, respectively. In both ascidian species, a significant reduction in cell viability was observed against three tumor cell lines at higher concentration 35 and 50 µM for 72 h while lower concentration did not induce substantial cell viability reduction. Similar to this case study, a pyrrole alkaloid lamellarin N from the unidentified ascidian, showed cytotoxicity against SK-MEL-5 (IC50 1.87 µM) and UACC-62 (IC50 9.88 µM), respectively (Reddy et al. 1997). Meenakshi et al. (2013) have reported anti-immunomodulatory activity of P. nigra extract against sarcoma 180 (S-180) cells, 100% toxicity was observed at the concentration 0.60 mg/mL. Additionally, the extract of Didemnum ligulum exhibited modest cytotoxicity against HCT-8 cells with IC50 35.3 µg/mL and the extract of D. psammatodes against Molt-4 cells with IC50 35.3 µg/mL (Jimenez et al. 2003; Takeara et al. 2008). The fraction of Eudistoma vannamei showed potent anti-proliferative activity against human promyelocytic leukemia cells (HL-60) with IC50 value 1.85 µg/mL and induced strong apoptosis and necrosis of HL-60 cells (Jimenez et al. 2008). CiEx, a partially purified extract from Ciona intestinalis (Russo et al. 2008) and PI-8 fraction isolated from P. indicum (Rajesh et al. 2010) and methyl ester mixtures of D. psammatodes exhibited strong apoptotic inhibition against HL-60 cells (Takeara et al. 2008). It is promising that the crude extract of ascidian P. nigra inhibits cell division and trigger apoptosis similar to anti-tumor compound plitidepsin from A. albicans (Molinski et al. 2009).

Table 2.

Anti-tumor activity of methanol extracts of ascidians in three tumor cell lines determined by MTT assay

| Sample | Tumor cell lines | IC50 (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| P. arabica | HeLa | 42.52 |

| HT29 | 43 | |

| MCF-7 | 38.28 | |

| P. nigra | HeLa | 39.72 |

| HT29 | 35 | |

| MCF-7 | 34.76 |

Fig. 4.

The Anti-tumor activity of Phallusia spp. crude compounds against three tumor cell lines. a, b Anti-tumor activity of ascidian Phallusia arabica and P. nigra against HT-29 (colon cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer) and HeLa (cervical cancer) cells concentration ranging from 1 to 50 µM for 72 h. The results represent the mean ± SEM of replicates. One-way ANOVA was calculated between control and treated cells. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Changes in steroid metabolic pathway

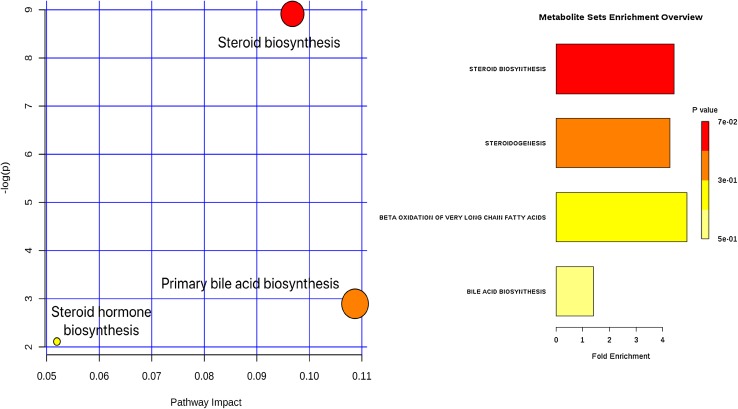

To further examine the impact of Phallusia ascidians, selected metabolites and to identify possible biochemical pathways that were affected in ascidians metabolism. Metabolomic pathway analysis (MetPA) was constructed to reveal the most relevant biochemical pathways. The pathway analysis displayed that the metabolites avenasterol, cholesterol; campesterol, desmosterol played important roles in values of pathway impact higher than 0.06, whereas 18 metabolites were found from the GC–MS-based study related to steroid biosynthesis and primary bile acid metabolism. The top three metabolic pathways of ascidian metabolites involved by p value, including the following: (1) steroid biosynthesis, (2) primary bile acid biosynthesis, (3) steroid hormone biosynthesis metabolism (Fig. 5; Table 3).

Fig. 5.

Metabolic pathway analysis of ascidian metabolites. The size and color of each circle were based on pathway impact and p value, respectively

Table 3.

Marine ascidian metabolites metabolomics pathway analysis

| S. no. | Pathway | Total | Hits | Metabolites | Raw p | Log p | FDR | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Steroid biosynthesis | 35 | 4 | Avenasterol, cholesterol; campesterol, desmosterol | 0.004 | 8.91 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| 2 | Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 46 | 2 | Cholesterol; 4-cholesten-7α,12α-diol-3-one | 0.05 | 2.89 | 1 | 0.04 |

| 3 | Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 72 | 2 | Cholesterol, 5a-pregnane-3,20-dione | 0.12 | 2.11 | 1 | 0.01 |

Biosynthesis of marine steroids remains to be least studied (Ivanchina et al. 2011; Kanazawa 2001). The data presented in this study demonstrated the biosynthesis of cholesterol to active metabolites 17-hydroxyprogesterone, androgen and estrogen from marine ascidians (Fig. 6), and it always changes significantly in various diseases (Falkenstein et al. 2000). In this study, a higher amount of lipid and sterol metabolites (i.e., cholestane steroids; ergostane steroids and stigmastanes) were found in both ascidians crude extracts and inhibited promising anti-tumor activity against MCF-7 breast cancer carcinoma with IC50 34.76 µM. According to the above evidence, we proposed that a combination of cholest-5-en-3-ol and 5α-androstane-3-17-dione metabolites could be involved in inhibiting the steroid biosynthesis and steroid compounds are cytotoxic to the carcinoma cells (Falkenstein et al. 2000).

Fig. 6.

Steroidogenesis metabolic pathway of cholesterol biosynthesis to active steroids. Enrichment analysis showed pathway impact value p < 0.05

Changes in primary bile acid biosynthesis

The end product of metabolite cholesterol utilization are the bile acids. In our study, metabolite, cholesterol and cholesten-7alpha,12alpha-diol-3-one were found in both the ascidian species, and both played significant roles in values of primary bile acid biosynthesis pathway impact higher than 0.04. Remarkably, the crude extracts of ascidian P. nigra showed strong anti-tumor activity against HT29 colon cancer (IC50 35 µM). Previous experimental studies were proposed a mechanism of bile acids in colon cancer cells. Exposure of colon carcinoma cells to high deoxycholic concentrations increases the formation of reactive oxygen species, causing oxidative stress and also increases DNA damage (Thériault and Labrie 1991; Kanehisa et al. 2013). These findings indicated the involvement of ascidian metabolites in bile acids biosynthesis, and bile acids are cytotoxic to carcinoma cells.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that an untargeted GC–MS-based metabolomic profiling of Indian ascidian Phallusia spp. led to the identification potential endogenous metabolites that may have drug-like properties and suggests new therapeutic targets. Our findings indicate that the secondary metabolites of ascidians are involved in the chemical defense of invasive species P. nigra and have a rich resource of compounds with cytotoxic properties. This study indicated that the presence of several metabolites in Phallusia spp. crude extracts can be used efficiently in pharmaceutical industries for drug discovery program. Results of cell cytotoxicity analysis indicated that crude extract of P. nigra inhibited cell proliferation in all of the three cell lines tested compared to P. arabica and showed higher growth inhibition against breast cancer (MCF-7) and colon carcinoma (HT29) cells. We performed pathway analysis using the results of GC–MS-based metabolites to find the biomarkers. Results of this study confirmed the biosynthesis of steroids and primary bile acids from cholesterol and their involvement in growth inhibition of carcinoma cells (Bernstein et al. 2009; Kanehisa et al. 2013). However, additional bioassays, compound separation and structural elucidation of finding out of novel marine drugs from Indian ascidians with potential therapeutic in the treatment of breast cancer disease are needed.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Author Satheesh gratefully thanks the course Coordinator Prof. Emilio De Domenico and Prof. Salvatore Giacobbe, UNIME, for all the support and encouragement and approval for this submission. Authors thank Dr. Donatella Del Bufalo, Istituto Nationale Tumori Regina Elena, Roma, Italy, for tumor cell lines and guidance in MTT bioassay methods. Authors thank Mr. Subhash for his help in specimen collection.

Author contributions

SKP and UM conceived and designed the research experiments; SKP and VA collected samples, extraction, data analysis and performed bioassays; MP performed GC–MS analysis and data analysis; SKP, UM, MP analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Funding

Author Satheesh thanks the University of Messina for the award of Non-EU doctoral research fellowship during 2013–2015. Author Umamaheswari thanks Department of Science and Technology-SERB DST-SERB (SB/YS/LS-374/2013) for the award of Young Scientist award.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1273-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Satheesh Kumar Palanisamy, Phone: +353899608763, Email: indianscientsathish@gmail.com.

Umamaheswari Sundaresan, Email: myscienceworld@gmail.com.

References

- Ali HAJ, Tamilselvi M. Ascidians in coastal water. Basel: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Ananthan G, Selva Prabhu A. New lead molecules from ascidian Phallusia nigra (Savigny, 1816) for type-2 diabetes mellitus targeting aldose reductase: an in silico approach. Univ J App Sci. 2014;2:73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein H, Bernstein C, Payne CM, Dvorak K. Bile acids as endogenous etiologic agents in gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(27):3329–3340. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YH, Sertic S, Kim HK, Wilson EG, Michopoulos F, Lefeber AW, Erkelens C, Prat Kricun SD, Verpoorte R. Classification of Ilex species based on metabolomic fingerprinting using nuclear magnetic resonance and multivariate data analysis. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(4):1237–1245. doi: 10.1021/jf0486141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson BS. Ascidians: producers of amino acid-derived metabolites. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1771–1791. doi: 10.1021/cr00021a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M. Multiple actions of steroid hormones—a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharma Rev. 2000;52(4):513–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farag MA, Porzel A, Al-Hammady MA, Hegazy MEF, Meyer A, Mohamed TA. Soft corals biodiversity in the egyptian red sea: a comparative ms and nmr metabolomics approach of wild and aquarium grown species. J Proteome Res. 2016;15(4):1274–1287. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes D, Loi B, Porte C. Biosynthesis and metabolism of steroids in molluscs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;127(3):189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraldeschi R, Sharifi N, Auchus RJ, Attard G. Molecular pathways: inhibiting steroid biosynthesis in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(13):3353–3359. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XQ, Thakur K, Chen GH, Hu F, Zhang JG, Zhang HB, Wei ZJ. Metabolic effect of 1-deoxynojirimycin from mulberry leaves on db/db diabetic mice using LC–MS based metabolomics. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(23):4658–4667. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanchina NV, Kicha AA, Stonik VA. Steroid glycosides from marine organisms. Steroids. 2011;76(5):425–454. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez PC, Fortier SC, Lotufo TM, Pessoa C, Moraes MEA, de Moraes MO, Costa-Lotufo LV. Biological activity in extracts of ascidians (Tunicata, Ascidiacea) from the northeastern Brazilian coast. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2003;287(1):93–101. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00499-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez PC, Wilke DV, Takeara R, Lotufo TM, Pessoa C, de Moraes MO. Cytotoxic activity of a dichloromethane extract and fractions obtained from Eudistoma vannamei (Tunicata: Ascidiacea) Comp Biochem Phys Part A Mol Integr Phys. 2008;151(3):391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa A. Sterols in marine invertebrates. Fish Sci. 2001;67(6):997–1007. doi: 10.1046/j.1444-2906.2001.00354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. Data, information, knowledge and principle: back to metabolism in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42(D1):D199–D205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koplovitz G, McClintock JB. An evaluation of chemical and physical defences against fish predation in a suite of seagrass-associated ascidians. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2011;407(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.06.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meenakshi VK, Paripooranaselvi M, Sankaravadivoo S, Gomathy S, Chamundeeswari KP. Immunomodulatory activity of Phallusia nigra (Savigny, 1816) against S-180. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2013;2(8):286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Molinski TF, Dalisay DS, Lievens SL, Saludes JP. Drug development from marine natural products. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(1):69–85. doi: 10.1038/nrd2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odate JR, Pawlik JR. The role of vanadium in the chemical defence of the solitary tunicate, Phallusia nigra. J Chem Ecol. 2007;2007:33(3):643–654. doi: 10.1007/s10886-007-9251-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy SK, Rajendran NM, Marino A. Natural products diversity of marine ascidians (Tunicates; Ascidiacea) and successful drugs in clinical development. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2017;7(1):1–111. doi: 10.1007/s13659-016-0115-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy SK, Trisciuoglio D, Zwergel C, Del Bufalo D, Mai A. Metabolite profiling of ascidian Styela plicata using LC–MS with multivariate statistical analysis and their antitumor activity. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2017;32(1):614–623. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1266344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Párraga I, López-Torres J, Andrés F, Navarro B, del Campo JM, García-Reyes M, et al. Effect of plant sterols on the lipid profile of patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Randomised, experimental study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;11(1):73. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-11-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohnert G. Diatom/copepod interactions in plankton: the indirect chemical defence of unicellular algae. Chem Biochem. 2005;6:946–959. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh RP, Santhana Ramasamy M, Murugan A. Anticancer activity of the ascidian Polyclinum indicum against cervical cancer cells (HeLa) mediated through apoptosis induction. Med Chem. 2010;6(6):396–405. doi: 10.2174/157340610793564009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravinder K, Vijender Reddy A, Krishnaiah P, Ramesh P, Ramakrishna S, Laatsch H. Isolation and synthesis of a novel β-carboline guanidine derivative tiruchanduramine from the Indian ascidian Synoicum macroglossum. Tetra Lett. 2005;46(33):5475–5478. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2005.06.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MVR, Faulkner DJ, Venkateswarlu Y, Rao MR. New lamellarin alkaloids from an unidentified ascidian from the Arabian Sea. Tetrahedron. 1997;53(10):3457–3466. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00073-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MVR, Rao MR, Rhodes D, Hansen M, Rubins K, Bushman F. Lamellarin alpha-20 sulfate, an inhibitor of HIV-1 integrase active against HIV-1 virus in vivo. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1901–1907. doi: 10.1021/jm9806650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo GL, Ciarcia G, Presidente E, Siciliano RA, Tosti E. Cytotoxic and apoptogenic activity of a methanolic extract from the marine invertebrate Ciona intestinalis on malignant cell lines. Med Chem. 2008;4:106–109. doi: 10.2174/157340608783789121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satheeshkumar P. Mangrove vegetation and community structure of brachyuran crabs as ecological indicators of Pondicherry coast, South east coast of India. Iran J Fish Sci. 2012;11(1):184–203. [Google Scholar]

- Takeara R, Jimenez PC, Wilke DV, de Moraes MO, Pessoa C, Lopes NP. Antileukemic effects of Didemnum psammatodes (Tunicata: Ascidiacea) constituents. Comp Biochem Phys Part A Mol Integr Phys. 2008;151(3):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamilselvi M, Akram AS, Arshan MK, Sivakumarn V. Comparative study on bioremediation of heavy metals by solitary ascidian, Phallusia nigra, between Thoothukudi and Vizhinjam ports of India. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2015;121:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thériault C, Labrie F. Multiple steroid metabolic pathways in ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;38(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(91)90121-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tianero MDB, Kwan JC, Wyche TP, Presson AP, Koch M, Barrows LR, Bugni TS, Schmidt EW. Species specificity of symbiosis and secondary metabolism in ascidians. ISME J. 2015;9(3):615–628. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetter WA. A GC/ECNI-MS method for the identification of lipophilic anthropogenic and natural brominated compounds in marine samples. Anal Chem. 2011;73(20):4951–4957. doi: 10.1021/ac015506u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Wishart DS. Web-based inference of biological patterns, functions and pathways from metabolomic data using MetaboAnalyst. Nature Protoc. 2011;6(6):743–760. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Wishart DS. Using MetaboAnalyst 3.0 for comprehensive metabolomics data analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 2016;14:10. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.