Abstract

Background

Adalimumab is approved for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), plaque psoriasis, and other inflammatory conditions.

Objective

Our objective was to examine the safety of adalimumab administered every other week (EOW) and every week (EW) in patients with HS and psoriasis and to investigate informative data from non-dermatologic indications.

Methods

The safety of adalimumab 40-mg EOW versus EW dosing was examined during placebo-controlled and open-label study periods in patients with HS (three studies), psoriasis (two studies), Crohn’s disease (six studies), ulcerative colitis (three studies), and rheumatoid arthritis (one study).

Results

No new safety risks or increased rates of particular adverse events (AEs) were identified with EW dosing. In patients with HS or psoriasis, the overall safety of adalimumab 40-mg EOW and EW was generally comparable. In studies of adalimumab for non-dermatologic indications, including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis, the overall AE rates were similar for EW and EOW dosing.

Conclusion

In patients with HS or psoriasis, the safety of adalimumab EW and EOW was comparable and consistent with the expected adalimumab AE profile. The safety of adalimumab EW dosing in patients with dermatologic conditions is supported by data comparing adalimumab EW and EOW dosing for Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00918255, NCT01468207, NCT01468233, NCT00645814, NCT00077779, NCT00055497, NCT01070303, NCT00195715, NCT00348283, NCT00385736, NCT00408629, and NCT00573794.

Key Points

| Adalimumab has a well-established safety profile across multiple indications. |

| In patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, psoriasis, and non-dermatologic indications, the safety of adalimumab 40-mg every other week and every week dosing regimens was comparable. |

| The current analysis supports and further adds to the known safety profile of adalimumab. |

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic painful skin disease characterized by abscesses, nodules, and scarring predominantly in the axillary and groin regions [1]. Prevalence estimates for HS range from 0.05 to 4% [2–4]. Elevated concentrations of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) have been found in the serum and skin lesions of patients with HS [5, 6] and psoriasis [7, 8].

Adalimumab is a fully human, highly specific anti-TNF monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of moderate to severe HS and chronic plaque psoriasis [9, 10]. Adalimumab is also indicated by the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult and pediatric Crohn’s disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and uveitis [9, 10].

For patients with HS, the recommended dosage of adalimumab is an initial dose of 160 mg followed by an 80-mg dose 2 weeks later and subsequent 40-mg doses every week (EW) thereafter. For adult patients with psoriasis, the recommended adalimumab dosage is an initial dose of 80 mg, followed by subsequent 40-mg doses every other week (EOW) starting 1 week after the initial dose [9]. The dosing recommendation for adult plaque psoriasis was updated in the EU in 2015 to state that patients with inadequate response with EOW dosing may benefit from an increase in dosing frequency to 40 mg EW after 16 weeks [9, 11].

The objective of this analysis was to examine the safety of adalimumab 40 mg EOW and EW in patients with HS or psoriasis during placebo-controlled and extended open-label study periods and to explore complementary data from other indications (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis) for which direct comparisons of safety data from EOW and EW dosing in the same study were available.

Methods

Study Designs

Hidradenitis Suppurativa

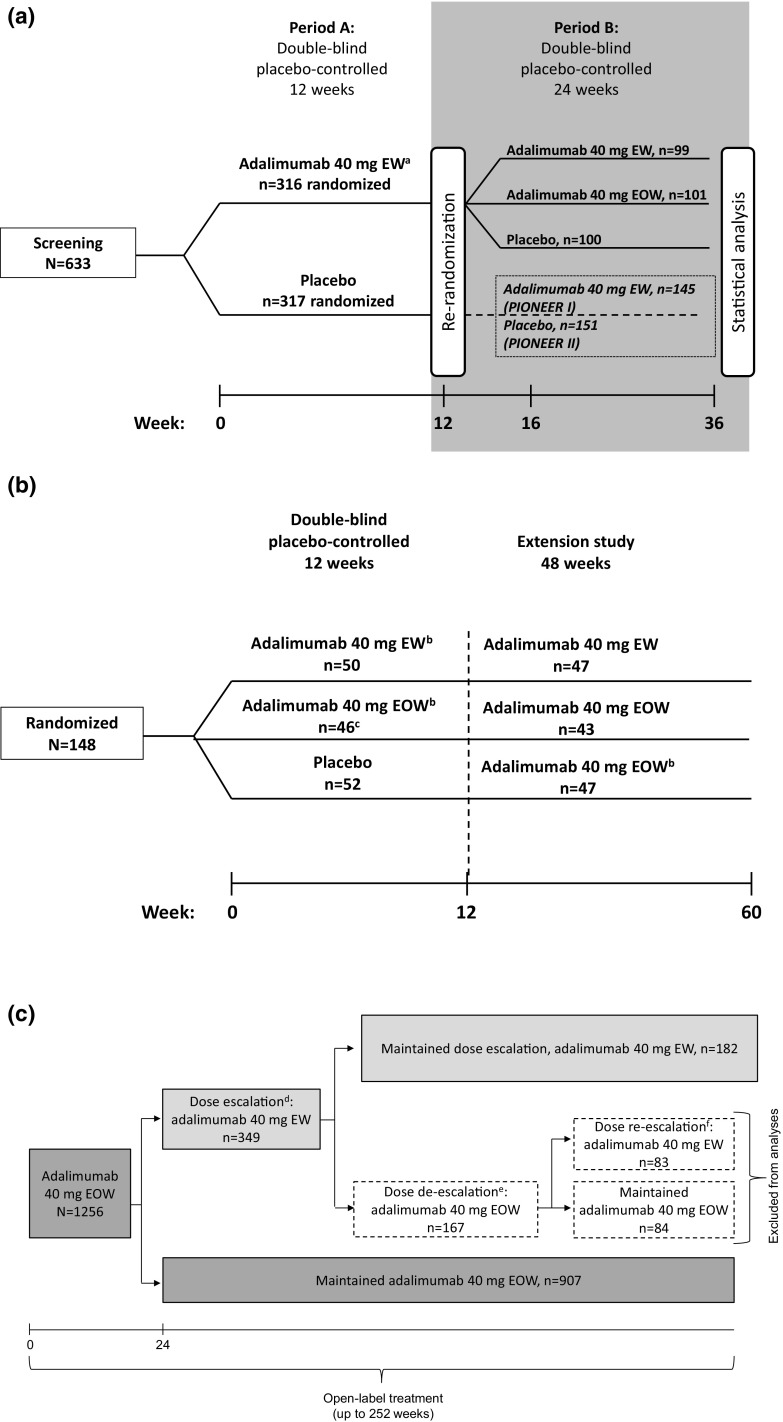

Adalimumab was evaluated for the treatment of HS in a phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (NCT00918255) [12] and two phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (PIONEER I [NCT01468207] and II [NCT01468233]) [13]. In the phase II study, patients were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to receive 16 weeks of treatment with placebo, adalimumab 40 mg EOW, or adalimumab 40 mg EW. In the phase III studies, patients with moderate to severe HS received adalimumab 40 mg EW or placebo in period A for 12 weeks. In period B, patients who received adalimumab 40 mg EW in period A were re-randomized to receive adalimumab 40 mg EOW, 40 mg EW, or placebo for 24 weeks; data from these patients directly comparing adalimumab EOW or EW and placebo were included in this analysis (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Study designs of a the hidradenitis suppurativa phase III, PIONEER I and II studies, b the psoriasis phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, and c the psoriasis open-label study. EOW every other week, EW every week, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, PASI50 ≥ 50% improvement in PASI, PASI75 ≥ 75% improvement in PASI. aStarting at week 4 following 160 mg at week 0 and 80 mg at week 2. bPatients receiving adalimumab 40 mg EW, initially received adalimumab 80 mg at weeks 0 and 1 and then 40 mg weekly starting at week 2; patients receiving adalimumab 40 mg EOW, initially received adalimumab 80 mg at week 0 (week 13 for those randomized to placebo) and then 40 mg EOW starting 1 week later. cOne patient was randomized but withdrew consent and did not receive treatment. dIf < PASI50 (relative to baseline of original study start) at any time from week 24 on. eIf ≥ PASI75 (relative to baseline of original study start) at any time after dose escalation. fIf < PASI50 (relative to baseline of original study start) at any time after de-escalating, after which patients remained on adalimumab 40 mg EW

Psoriasis

The safety of adalimumab was assessed in a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in adults with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis (NCT00645814) [14]. In this trial, patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive placebo, adalimumab 40 mg EOW, or adalimumab 40 mg EW for 12 weeks followed by a 48-week extension phase (Fig. 1b); only data from the initial 12-week, double-blind placebo-controlled period directly comparing EOW and EW dosing and placebo were included in this analysis.

Patients completing the extension and patients from other phase II/III studies of adalimumab [14–18] were eligible for enrollment in another study (NCT00195676) [19], in which adults with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis received open-label adalimumab EOW or EW for up to 252 weeks (Fig. 1c). In this study, patients received adalimumab 40 mg EOW for 24 weeks. From weeks 24 to 252, patients with < 50% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score could escalate their dose to adalimumab 40 mg EW. Patients who achieved ≥ 75% improvement in PASI score were de-escalated to adalimumab 40 mg EOW but were eligible to be re-escalated to EW dosing if PASI improvement fell to < 50%. Patients who re-escalated could not de-escalate their adalimumab dose for the remainder of the study. Data after dose de-escalation to adalimumab 40 mg EOW were not included in this analysis (Fig. 1c)

Other Indications

Three double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, including two in Crohn’s disease (NCT00077779 [20] and NCT00055497 [21]) and one in rheumatoid arthritis [22], compared the safety of placebo, adalimumab 40 mg EOW, and adalimumab 40 mg EW; the designs and results of these studies have been reported previously [20–22]. The safety of open-label adalimumab 40 mg EOW versus 40 mg EW was assessed in seven studies, including four in Crohn’s disease (NCT00077779 [20], NCT00055497 [21]/NCT01070303, NCT00195715 [23], and NCT00348283 [24]) and three in ulcerative colitis (NCT00385736 [25], NCT00408629 [26], and NCT00573794). Dose escalation to open-label 40-mg EW dosing was performed in patients with sustained non-response to treatment or recurrent disease flare.

Statistical Methods

Adverse events (AEs) are presented as number of events and rate of events per 100 patient-years (E/100 PY). Treatment-emergent AEs were defined as any AE with an onset date on or after first dose of study medication in the study period and up to 70 days after the last dose of study medication.

Patients provided informed consent, and individual study protocols were approved by independent ethics committees or institutional review boards at each site.

Results

Disposition of the Patients

For HS, this analysis included 153 patients with data from the phase II study and 300 patients with data from period B of the two phase III HS studies. Baseline demographic characteristics were generally similar between the placebo, EOW, and EW groups, except for a higher percentage of White patients in the EW group in the pooled phase III data (P = 0.016 between groups; Table 1 [27]).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of adults with hidradenitis suppurativa

| Characteristic | Phase II: 16-week placebo-controlled study | Phase III: pooled 24-week placebo-controlled period Ba | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO (n = 51) | EOW (n = 52) | EW (n = 51) | EW/PBO (n = 100) | EW/EOW (n = 101) | EW/EW (n = 99) | |

| Female | 36 (70.6) | 38 (73.1) | 36 (70.6) | 56 (56.0) | 65 (64.4) | 66 (66.7) |

| Age, years | 37.8 ± 12.1 | 36.1 ± 12.5 | 35.1 ± 10.7 | 36.5 ± 10.9 | 35.9 ± 10.5 | 34.8 ± 10.2 |

| White | 37 (72.5) | 36 (69.2) | 37 (72.5) | 81 (81.0) | 77 (76.2) | 90 (90.9) |

| Weight, kg | 96.5 ± 24.8 | 99.8 ± 26.8 | 95.4 ± 22.9 | 95.8 ± 26.1 | 92.6 ± 22.2 | 92.1 ± 21.2 |

| Tobacco user | 29 (56.9) | 26 (50.0) | 30 (58.8) | 54 (54.0) | 65 (64.4) | 59 (59.6) |

| Disease duration, years | 13.4 ± 10.4 | 10.9 ± 9.0 | 11.3 ± 9.1 | 11.6 ± 9.8 | 11.7 ± 8.0 | 11.8 ± 8.8 |

| Hurley stageb | ||||||

| I | 7 (13.7) | 9 (17.3) | 8 (15.7) | – | – | – |

| II | 29 (56.9) | 28 (53.8) | 28 (54.9) | 55 (55.0) | 52 (51.5) | 49 (49.5) |

| III | 15 (29.4) | 15 (28.8) | 15 (29.4) | 45 (45.0) | 49 (48.5) | 50 (50.5) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation

EOW every-other-week dosing of adalimumab, EW every-week dosing of adalimumab, PBO placebo

aEW/PBO indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by PBO treatment; EW/EOW indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by EOW treatment; EW/EW indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by continued EW treatment

bHurley stage disease classification is based on the presence and extent of abscesses and sinus tract formation [27]

In the phase II psoriasis trial, 52 patients received placebo, 45 adalimumab 40 mg EOW, and 50 adalimumab 40 mg EW. Most patients (140/147 [95%]) completed the 12-week double-blind period. In the long-term open-label extension psoriasis study, 1256 patients received EOW dosing between weeks 1 and 24, and 907 patients continued EOW dosing throughout the study; 349 escalated to EW dosing at or after week 24 (Fig. 1c). Of these 349 patients, 182 continued on EW dosing and 167 de-escalated to EOW dosing, with 83 of these patients re-escalating to EW dosing and 84 continuing with EOW dosing. Exposure was determined based on the time that patients were receiving each dosing regimen. Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were generally similar between the placebo, EOW, and EW groups in the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and between the open-label EOW and EW populations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of adults with psoriasis

| Characteristic | Phase II, 12-week placebo-controlled study | Open-label extension study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO (n = 52) | EOW (n = 45) | EW (n = 50) | EOW (n = 1256) | EW (n = 349) | |

| Female | 18 (34.6) | 13 (28.9) | 17 (34.0) | 406 (32.3) | 134 (38.4) |

| Age, years | 43.3 ± 13.1 | 45.8 ± 11.6 | 43.8 ± 13.3 | 44.4 ± 12.9 | 44.1 ± 11.6 |

| White | 48 (92.3) | 40 (88.9) | 45 (90.0) | 1157 (92.1) | 325 (93.1) |

| Weight, kg | 93.8 ± 23.2 | 93.3 ± 21.7 | 98.5 ± 23.2 | 92.3 ± 22.7 | 97.7 ± 23.8 |

| Tobacco user | 18 (34.6) | 10 (22.2) | 17 (34.0) | 420 (33.5) | 118 (33.8) |

| Disease duration, years | 19.1 ± 9.6 | 20.5 ± 13.0 | 18.4 ± 11.3 | 19 ± 11.6 | 18 ± 10.5 |

| PGA | |||||

| Moderate | 28 (53.8) | 14 (31.1) | 21 (42.0) | 618 (52.1) | 166 (48.3) |

| Severe | 15 (28.8) | 25 (55.6) | 21 (42.0) | 495 (41.7) | 155 (45.1) |

| Very severe | 4 (7.7) | 4 (8.9) | 4 (8.0) | 73 (6.2) | 23 (6.7) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation

EOW every-other-week dosing of adalimumab, EW every-week dosing of adalimumab, PBO placebo, PGA Physician Global Assessment

Duration of Exposure to Adalimumab Treatment

In the phase II HS study, exposure to adalimumab was similar across treatment groups. In the phase III HS studies, exposure to adalimumab during period B was similar in the placebo and EOW groups but slightly longer in the EW group (Table 3). In the psoriasis studies, exposure to adalimumab was similar in all treatment groups in the placebo-controlled analyses; during the open-label study, EOW exposure to adalimumab was longer than EW exposure.

Table 3.

Duration of exposure to adalimumab treatment in studies of adalimumab for adults with dermatologic conditions

| Exposure, days | HS | Psoriasis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo-controlled data | PBOa (n = 51) | EOWa (n = 52) | EWa (n = 51) | PBO (n = 52) | EOW (n = 45) | EW (n = 50) |

| 104.0 ± 25.6 | 112.9 ± 2.5 | 107.4 ± 20.1 | 82.9 ± 11.9 | 82.9 ± 10.8 | 81.8 ± 11.6 | |

| EW/PBOb (n = 100) | EW/EOWb (n = 101) | EW/EWb (n = 99) | ||||

| 116.1 ± 61.7 | 119.6 ± 61.7 | 130.4 ± 60.1 | ||||

| Open-label extension data | EOW (n = 1256) | EW (n = 349) | ||||

| 810.5 ± 432.6 | 232.7 ± 218.9 | |||||

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

EW/PBO indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by PBO treatment; EW/EOW indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by EOW treatment; EW/EW indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by continued EW treatment

EOW every-other-week dosing of adalimumab, EW every-week dosing of adalimumab, HS hidradenitis suppurativa, PBO placebo

aPhase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase

bPeriod B pooled 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase

Safety

Dermatologic Conditions

During the phase II trial in patients with HS, AE frequency was higher with adalimumab than with placebo but similar with adalimumab EW and EOW dosing (Table 4). The rates of AEs leading to discontinuation, serious AEs (SAEs), and infections were also similar between the EOW and EW groups; serious infections included one event with EOW dosing and two events with EW dosing. There were no deaths or cases of tuberculosis or opportunistic infection. There was one report of vocal cord neoplasm in the adalimumab EW group. There were two cases of new-onset/worsening psoriasis in the placebo group compared with none in the adalimumab groups. The incidence rate of injection-site reactions was higher in the EW group than in the EOW group; however, one patient in the EW group reported 8 of 11 events.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events in placebo-controlled analysis populations from studies of adalimumab for adults with hidradenitis suppurativa

| Events (E/100 PY) | Phase II, 16-week placebo-controlled study | Phase III pooled 24-week placebo-controlled period Ba | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO (n = 51) PY 14.5 |

EOW (n = 52) PY 16.2 |

EW (n = 51) PY 15.0 |

EW/PBO (n = 100) PY 31.8 |

EW/EOW (n = 101) PY 33.1 |

EW/EW (n = 99) PY 35.4 |

|

| Any AE | 105 (723.1) | 126 (783.6) | 124 (827.2) | 188 (591.2) | 163 (492.4) | 167 (471.8) |

| Serious AE | 2 (13.8) | 3 (18.5) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (6.3) | 7 (21.1) | 5 (14.1) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation | 0 | 2 (12.4) | 2 (13.3) | 2 (6.3) | 2 (6.0) | 2 (5.6) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

| AEs of special interest | ||||||

| Infections | 36 (247.9) | 32 (199.0) | 30 (200.1) | 55 (173.0) | 46 (139.0) | 45 (127.1) |

| Opportunistic infectionsb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious infections | 0 | 1 (6.2) | 2 (13.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.8) |

| Tuberculosis (active or latent) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injection-site reactions | 1 (6.9) | 1 (6.2) | 11 (73.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (2.8) |

| Lupus-like syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancyc | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NMSC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

| Worsening/new onset psoriasis | 2 (13.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.1) | 1 (3.0) | 3 (8.5) |

| CHF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.0) | 0 |

AE adverse event, CHF congestive heart failure, E events, EOW every-other-week dosing of adalimumab, EW every-week dosing of adalimumab, NMSC non-melanoma skin cancer, PBO placebo, PY patient-year

aPeriod B double-blind, placebo-controlled phase. EW/PBO indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by PBO treatment; EW/EOW indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by EOW treatment; EW/EW indicates an initial period of EW treatment followed by continued EW treatment

bExcluding oral candidiasis and tuberculosis

cExcluding lymphoma and NMSC in the phase II study and lymphoma, NMSC, melanoma, leukemia, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in the phase III pooled data

In the phase III pooled data in patients with HS, rates of any AE during period B with adalimumab EOW and EW and placebo were similar (Table 4). SAEs occurred more frequently with adalimumab EOW and EW than with placebo, whereas AEs leading to discontinuation occurred at similar rates across the three groups. Rates of infections in the EOW and EW groups were similar. No cases of opportunistic infection or tuberculosis and one event of non-melanoma skin cancer in the EOW dosing group were reported. There were three cases of new-onset/worsening psoriasis in the EW group compared with one each in the EOW and placebo groups. The incidence rate of injection site reactions was similar in the three groups.

In the phase II psoriasis study, the overall incidence of AEs and SAEs was higher in the EW group than in the EOW or placebo groups (Table 5). Few AEs leading to discontinuation occurred in the EOW (two events) and EW (three events) groups. The rate of infections was higher in the adalimumab EW group than in the EOW group. The incidence rate of worsening/new-onset psoriasis was highest in the placebo group, and the rate of injection-site reactions was highest in the EW group; other AEs of interest occurred at low, similar rates between the groups.

Table 5.

Summary of adverse events in studies of adalimumab for adults with psoriasis

| Events (E/100 PY) | Phase II, 12-week placebo-controlled study | Open-label extension study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO (n = 52) PY 11.9 |

EOW (n = 45) PY 10.2 |

EW (n = 50) PY 11.1 |

EOW (n = 1256) PY 2787.2 |

EW (n = 349) PY 222.4 |

|

| Any AE | 84 (705.9) | 62 (607.8) | 110 (991.0) | 6623 (237.6) | 517 (232.5) |

| Serious AE | 0 | 1 (9.8) | 3 (27.0) | 181 (6.5) | 17 (7.6) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation | 1 (8.4) | 2 (19.6) | 3 (27.0) | 80 (2.9) | 22 (9.9) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) |

| AEs of special interest | |||||

| Infections | 8 (67.2) | 8 (78.4) | 14 (126.1) | 2029 (72.8) | 144 (64.8) |

| Opportunistic infectionsa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) |

| Serious infectionb | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.0) | 33 (1.2) | 2 (0.9) |

| Tuberculosis (active or latent) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (0.2) | 0 |

| Injection-site reaction | 13 (109.2) | 8 (78.4) | 20 (180.2) | 174 (6.2) | 3 (1.3) |

| Lupus-like syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancyc | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.0) | 14 (0.5) | 3 (1.3) |

| NMSC | 0 | 1 (9.8) | 0 | 19 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| Worsening/new onset psoriasis | 4 (33.6) | 0 | 1 (9.0) | 43 (1.5) | 8 (3.6) |

| CHF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (0.2) | 3 (1.3) |

AE adverse event, CHF congestive heart failure, E events, EOW every-other-week dosing of adalimumab, EW every-week dosing of adalimumab, NMSC non-melanoma skin cancer, PBO placebo, PY patient-year

aExcluding oral candidiasis and tuberculosis

bExcluding tuberculosis in the placebo-controlled study, but including tuberculosis in the open-label study

cExcluding lymphoma and NMSC in the placebo-controlled study and excluding lymphoma, NMSC, melanoma, leukemia, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in the open-label study

During the open-label study, the rates of any AE and SAEs were similar between the EOW and EW dosing groups (Table 5). The rate of discontinuation due to an AE was higher with adalimumab EW than with adalimumab EOW. Because of the much larger exposures in the EOW group (2787.2 PY vs. 222.4 PY for EW), comparisons of other AEs of interest should be made with caution; however, the overall safety profile was similar in the EOW and EW groups.

Non-Dermatologic Conditions

In placebo-controlled Crohn’s disease studies, rates of any AE, SAEs, AEs leading to discontinuation, infections, serious infections, and other AEs of interest were similar between the EOW and EW groups (Table 6). In the placebo-controlled rheumatoid arthritis study, rates of any AE and SAEs were also similar between EOW and EW groups; AEs leading to discontinuation occurred more often in the EOW group than in the EW group. In the rheumatoid arthritis studies, infections and serious infections occurred at similar rates with EOW and EW dosing. Other AEs of interest also occurred at similar rates in the EOW and EW groups.

Table 6.

Summary of adverse events in placebo-controlled studies of adalimumab for adults with Crohn’s disease or rheumatoid arthritis

| Events (E/100 PY) | Crohn’s disease | Rheumatoid arthritis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBO (n = 279) PY 101.6 |

EOW (n = 279) PY 156.6 |

EW (n = 275) PY 162.3 |

PBO (n = 110) PY 37.4 |

EOW (n = 113) PY 48.4 |

EW (n = 103) PY 47.7 |

|

| Any AE | 1002 (986.2) | 1187 (758.0) | 1235 (760.9) | 944 (2524.1) | 1238 (2557.9) | 1087 (2278.8) |

| Serious AE | 49 (48.2) | 30 (19.2) | 32 (19.7) | 26 (69.5) | 18 (37.2) | 22 (46.1) |

| AE leading to discontinuation | 37 (36.4) | 26 (16.6) | 19 (11.7) | 3 (8.0) | 10 (20.7) | 5 (10.5) |

| AE leading to death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (8.0) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| AEs of special interest | ||||||

| Infection | 166 (163.4) | 226 (144.3) | 219 (134.9) | 64 (171.1) | 103 (212.8) | 99 (207.5) |

| Opportunistic infectiona | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Serious infection | 10 (9.8) | 7 (4.5) | 7 (4.3) | 0 | 2 (4.1) | 2 (4.2) |

| Tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injection-site reaction | 21 (20.7) | 62 (39.6) | 49 (30.2) | 11 (29.4) | 45 (93.0) | 67 (140.5) |

| Lupus-like syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancyb | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| NMSC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.1) | 0 |

| Worsening/new-onset psoriasis | 0 | 4 (2.6) | 7 (4.3) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 1 (2.1) |

| CHF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.3) | 0 | 0 |

AE adverse event, CHF congestive heart failure, E events, EOW every-other-week dosing of adalimumab, EW every-week dosing of adalimumab, NMSC non-melanoma skin cancer, PBO placebo, PY patient-year

aExcluding oral candidiasis and tuberculosis

bExcluding lymphoma, NMSC, melanoma, leukemia, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma

In the open-label portions of the Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis studies, the incidence rates of overall AEs, SAEs, and infections were higher in the EW groups than in the EOW groups (Table 7). However, there was no consistent trend for higher incidence rates in the EW dosing groups for other AEs of interest, including the rate of injection-site reactions, which was similar in the EW and EOW groups. In these studies, patients escalated to EW dosing for sustained non-response to treatment or recurrent disease flare.

Table 7.

Summary of adverse events in open-label studies of adalimumab for adults with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Events (E/100 PY) | Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOW (n = 660) PY 1259.9 |

EW (n = 638) PY 962.7 |

EOW (n = 460) PY 1332.6 |

EW (n = 440) PY 719.8 |

|

| Any AE | 5730 (454.8) | 5118 (531.6) | 2925 (219.5) | 2248 (312.3) |

| Serious AE | 332 (26.4) | 333 (34.6) | 182 (13.7) | 149 (20.7) |

| AE leading to discontinuation | 170 (13.5) | 137 (14.2) | 96 (7.2) | 84 (11.7) |

| AE leading to death | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (< 0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| AEs of special interest | ||||

| Infection | 1312 (104.1) | 1060 (110.1) | 674 (50.6) | 505 (70.2) |

| Opportunistic infectiona | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 1 (< 0.1) | 2 (0.3) |

| Serious infection | 77 (6.1) | 55 (5.7) | 44 (3.3) | 24 (3.3) |

| Tuberculosis | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (< 0.1) | 3 (0.4) |

| Lupus-like syndrome | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Injection-site reactions | 111 (8.8) | 41 (4.3) | 79 (5.9) | 39 (5.4) |

| Lymphoma | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

| Malignancyb | 13 (1.0) | 4 (0.4) | 8 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) |

| NMSC | 13 (1.0) | 7 (0.7) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) |

| Worsening/new-onset psoriasis | 23 (1.8) | 14 (1.5) | 10 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) |

| CHF | 1 (< 0.1) | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) |

AE adverse event, CHF congestive heart failure, E events, EOW every-other-week dosing of adalimumab, EW every-week dosing of adalimumab, NMSC non-melanoma skin cancer, PY patient-year

aExcluding oral candidiasis and tuberculosis

bExcluding lymphoma, NMSC, melanoma, leukemia, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma

Discussion

Adalimumab has a well-established safety profile across multiple indications based on more than 57,000 PY of exposure in clinical trials and postmarketing data [28–32]. The current analysis adds to the safety profile of adalimumab and demonstrates that, in adult patients with HS or psoriasis, the overall safety of 40-mg EOW and EW dosing regimens was comparable and consistent with the expected safety profile of adalimumab. The rates of AEs in the adalimumab EW and EOW dosing groups were similar in the studies for dermatologic indications, except the phase II psoriasis study, in which the overall rates of AEs and SAEs were higher in the EW group than in the EOW group. However, it should be noted that the PY of exposure in the psoriasis open-label extension were limited and were greater in the EOW group than in the EW group. There were few SAEs in the 12-week double-blind treatment period (three or fewer events in any treatment group); consequently, the observation of higher rates of AEs in the EW group may have been a chance finding. No new safety risks were identified with adalimumab EW dosing in the HS and psoriasis clinical development programs.

In the placebo-controlled studies of adalimumab for non-dermatologic indications, including Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis, overall AE rates were similar for EW and EOW dosing. In the open-label Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis studies, the patients who received EW dosing had escalated their dose due to sustained non-response to treatment or recurrent disease flares, which likely contributed to a higher rate of overall AEs and SAEs, particularly gastrointestinal-related events and other events that may be associated with worse underlying inflammatory bowel disease [20, 21, 23–26].

In addition, the majority of patients in the Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis studies were receiving concomitant therapies, such as corticosteroids or other immunosuppressant therapies, which also may have confounded the results [20–26]. Nevertheless, there was no clear or consistent trend between dosing frequency and the rates of other AEs of interest for adalimumab in the non-dermatologic indication studies.

The product labeling for adalimumab recommends 40-mg EW dosing for patients with HS and 40-mg EOW dosing for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis after the initial loading dose(s). The European Medicines Agency approved an amendment to the adalimumab psoriasis dosing in 2015 based on additional data [11]. Specifically, “Beyond 16 weeks, patients with inadequate response may benefit from an increase in dosing frequency to 40 mg every week” [10]. In patients with an inadequate response after the increased dosing frequency, the benefit-to-risk ratio should be reconsidered; in patients subsequently achieving an adequate response, the dosage may be reduced to 40 mg EOW. Based on the findings from this analysis, no new safety concerns were identified with adalimumab EW dosing compared with EOW dosing.

Overall, across all the studies examined, there was no clear trend of specific AEs occurring at a greater frequency with EW dosing versus EOW dosing. However, limitations of the analysis include a short study duration for placebo-controlled portions of the studies and small numbers of patients or imbalances in PY of exposure in some analysis groups. Patients with HS received adalimumab 40 mg EW for 12 weeks before entering period B of the phase III studies, possibly resulting in some selection bias for patients who were already tolerating adalimumab EW dosing to continue into period B. However, in the phase II, 16-week HS study in which patients had no prior adalimumab treatment, the overall safety of double-blind treatment with adalimumab was similar for patients receiving EW or EOW dosing [12]. In addition, because dose escalation in some studies was initiated in response to inadequate disease control, patients whose dose was escalated may represent a different patient population than patients who did not undergo dose escalation; worsening underlying disease could have affected the rates of AEs. Furthermore, because of inherent differences among patients with different diseases, as well as disparities in concomitant medications and other factors, comparisons of AE rates across indications should be made with caution. Finally, because safety was not a primary outcome of the examined studies, no statistical tests of significance were performed on the safety data.

Conclusion

In this analysis of available safety data from EW and EOW dosing in patients with HS or psoriasis, the overall safety of adalimumab EW and EOW dosing regimens was comparable and consistent with the expected AE profile of adalimumab. The safety of EW adalimumab dosing in patients with dermatologic conditions is supported by data from studies comparing EW and EOW dosing of adalimumab for non-dermatologic indications, including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Maria Hovenden, PhD, Richard Edwards, PhD, and Janet Matsuura, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC, and was supported by AbbVie.

Funding

AbbVie funded the studies, contributed to their design, and was involved in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data and in the writing, review, and approval of the publication.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Caitriona Ryan has acted as an advisor and/or speaker for AbbVie, Aqua, Dermira, Dr. Reddy’s, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Medimetriks, Novartis, Regeneron-Sanofi, UCB, and Xenoport. Jeffrey M. Sobell has received honoraria and/or research funding from Amgen, AbbVie, Janssen, Celgene, Novartis, Lilly, Lycera, and Merck. Craig L. Leonardi has received funding from AbbVie, Actavis, Amgen, Celgene, Coherus, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Leo, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Stiefel, UCB, and Wyeth. Charles W. Lynde has received funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer, Celgene, Coherus, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Innovaderm, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Merck, MSD, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Xoma and reimbursement of traveling, accommodation, and hospitality expenses from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Valeant. Wendell C. Valdecantos and Barbara A. Hendrickson are employees of AbbVie, Inc. and may own AbbVie stock and/or stock options. Mahinda Karunaratne was an employee of AbbVie, Inc. at the time of this research and may own AbbVie stock and/or stock options.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the individual studies included in these analyses.

Contributor Information

Caitriona Ryan, Phone: +358 83 868 5522, Email: caitrionaryan80@gmail.com.

Jeffrey M. Sobell, Email: jsobell@skincarephysicians.net

Craig L. Leonardi, Email: Craig.Leonardi@centralderm.com

Charles W. Lynde, Email: derma@lynderma.com

Mahinda Karunaratne, Email: nivpat@comcast.net.

Wendell C. Valdecantos, Email: wendell.valdecantos@abbvie.com

Barbara A. Hendrickson, Email: barbara.hendrickson@abbvie.com

References

- 1.Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90(1062):216–221. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Revuz JE, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P, Viallette C, Gabison G, Pouget F, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two case-control studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(4):596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(2 Pt 1):191–194. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cosmatos I, Matcho A, Weinstein R, Montgomery MO, Stang P. Analysis of patient claims data to determine the prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(3):412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Increased serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: is there a basis for treatment with anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha agents? Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89(6):601–603. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, Dik WA, Laman JD, Prens EP. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(6):1292–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ettehadi P, Greaves MW, Wallach D, Aderka D, Camp RD. Elevated tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) biological activity in psoriatic skin lesions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96(1):146–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, Ciragil P. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediat Inflamm. 2005;5:273–279. doi: 10.1155/MI.2005.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humira®. adalimumab. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc.; 2016.

- 10.Humira Summary of Product Characteristics. 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu. Accessed 19 Apr 2016.

- 11.European Medicines Agency. Humira: procedural steps taken and scientific information after the authorisation. London, United Kingdom. 2016. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Procedural_steps_taken_and_scientific_information_after_authorisation/human/000481/WC500050869.pdf. Accessed 3 May 2016.

- 12.Kimball AB, Kerdel F, Adams D, Mrowietz U, Gelfand JM, Gniadecki R, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a parallel randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(12):846–855. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, Gottlieb AB, Papp KA, Zouboulis CC, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):422–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon KB, Langley RG, Leonardi C, Toth D, Menter MA, Kang S, et al. Clinical response to adalimumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: double-blind, randomized controlled trial and open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(4):598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menter A, Tyring SK, Gordon K, Kimball AB, Leonardi CL, Langley RG, et al. Adalimumab therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomized, controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saurat JH, Stingl G, Dubertret L, Papp K, Langley RG, Ortonne JP, et al. Efficacy and safety results from the randomized controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. methotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION) Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(3):558–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon KB, Blum RR, Papp KA, Matheson R, Bolduc C, Hamilton T, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Psoriasis Forum. 2007;13:4–11. doi: 10.1177/247553030713a00101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larian A, Emer JJ, Gordon K, Blum R, Okun M, Gu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of a second adalimumab treatment cycle in psoriasis patients who relapsed after adalimumab discontinuation or dosage reduction: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Psoriasis Forum. 2011;17:88–96. doi: 10.1177/247553031117a00201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonardi C, Sobell JM, Crowley JJ, Mrowietz U, Bao Y, Mulani PM, et al. Efficacy, safety and medication cost implications of adalimumab 40 mg weekly dosing in patients with psoriasis with suboptimal response to 40 mg every other week dosing: results from an open-label study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(3):658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(1):52–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh DG, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance treatment of Crohn’s disease: results of the CLASSIC II trial. Gut. 2007;56(9):1232–1239. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Putte LB, Atkins C, Malaise M, Sany J, Russell AS, van Riel PL, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab as monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis for whom previous disease modifying antirheumatic drug treatment has failed. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(5):508–516. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.013052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panaccione R, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, D’Haens GR, Robinson AM, et al. Adalimumab sustains clinical remission and overall clinical benefit after 2 years of therapy for Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(12):1296–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Sandborn WJ, Wolf DC, Geboes K, Colombel JF, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains mucosal healing in patients with Crohn’s disease: data from the EXTEND trial. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):1102–1111. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, D’Haens G, Hanauer S, Schreiber S, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60(6):780–787. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.221127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):257–265 e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurley HJ. Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and familial benign pemphigus: surgical approach. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH, editors. Dermatologic surgery. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1989. pp. 729–739. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, McIlraith MJ, Lacerda AP. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(4):517–524. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asgharpour A, Cheng J, Bickston SJ. Adalimumab treatment in Crohn’s disease: an overview of long-term efficacy and safety in light of the EXTEND trial. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013;6:153–160. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S35163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonardi C, Papp K, Strober B, Reich K, Asahina A, Gu Y, et al. The long-term safety of adalimumab treatment in moderate to severe psoriasis: a comprehensive analysis of all adalimumab exposure in all clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12(5):321–337. doi: 10.2165/11587890-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menter A, Thaci D, Papp KA, Wu JJ, Bereswill M, Teixeira HD, et al. Five-year analysis from the ESPRIT 10-year postmarketing surveillance registry of adalimumab treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):410–419.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubinsky MC, Rosh J, Faubion WA, Jr, Kierkus J, Ruemmele F, Hyams JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of escalation of adalimumab therapy to weekly dosing in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(4):886–893. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]