Abstract

The innate immune response in the central nervous system (CNS) is implicated as both beneficial and detrimental to health. Integral to this process are microglia, the resident immune cells of the CNS. Microglia express a wide variety of pattern-recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors, that detect changes in the neural environment. The activation of microglia and the subsequent proinflammatory response has become increasingly relevant to synucleinopathies, including Parkinson's disease the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disease. Within these diseases there is evidence of the accumulation of endogenous α-synuclein that stimulates an inflammatory response from microglia via the Toll-like receptors. There have been recent developments in both new and old pharmacological agents designed to target microglia and curtail the inflammatory environment. This review will aim to delineate the process of microglia-mediated inflammation and new therapeutic avenues to manage the response.

Keywords: TLR, toll-like receptor 2, synucleinopathies, Parkinson's disease, nfkb pathway, inflammation, neuroinflammation

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), and multiple system atrophy (MSA) are a group of neurodegenerative diseases called synucleinopathies and are characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies, neuroinflammation, and neuronal loss (Ouchi et al., 2009; Chung et al., 2010). The exact etiology of disease pathogenesis is still debated, yet PD and DLB comprise the second most prevalent neurological disease and second leading cause of dementia, respectively (McKeith et al., 1996; de Lau and Breteler, 2006; Braak and Del Tredici, 2017). The primary constituent of Lewy bodies is α-synuclein (αSyn), from which the name synucleinopathy is given (Spillantini et al., 1997, 1998; Baba et al., 1998; Braak et al., 2003). αSyn garnered significant interest after a number of mutations, namely A53T and A30P, were found in familial cases of PD (Polymeropoulos et al., 1996, 1997; Krüger et al., 1998; Athanassiadou et al., 1999; Singleton et al., 2003; Emmanouilidou et al., 2011). Despite the existence of these familial forms, 90% of PD cases are sporadic and manifest in a predictable clinical pattern as defined by Braak stages 1–6 (Bernheimer et al., 1973; Braak et al., 2003; Fahn, 2003; Braak and Del Tredici, 2008).

A growing body of research has focused on elucidating and modulating the processes of neuroinflammation that occur in synucleinopathies. Within the central nervous system (CNS), microglia are immune cells responsible for surveying and protecting their local environments. The relationship between neuronal loss and microglial activation is not definitively established, but irrespective of the disease initiating event microglial activation seems to be an integral potentiator of the disease process (as reviewed by; Block et al., 2007). Neurons express and release αSyn into the surrounding environment (Lee et al., 2005; Kim C. et al., 2016) and microglia recognize this with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and subsequently produce a proinflammatory response (Zhang et al., 2005; West et al., 2006; Su et al., 2008; Vezzani et al., 2011). The importance of microglia-mediated inflammatory responses is strengthened by the observation that dopaminergic neuron loss is correlated with microglial upregulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and the release of nitric oxide (NO) (Knott et al., 2000; Gao et al., 2008), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (McCoy et al., 2006; Takeuchi et al., 2006), and interleukin (IL)−1β (Ferrari et al., 2006). This inflammatory state can be measured with [11C](R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and such studies demonstrate progressive microglial activation during early pathogenesis, followed by sustained microglial activation during mid to late disease stages (Gerhard et al., 2006a; Ouchi et al., 2009). Relevant to synucleinopathies, amoeboid microglia, a morphology typical of activation, are associated with disease pathology (αSyn) in the brains of patients with diagnosed Parkinson's disease or incidental Lewy Body disease (Doorn et al., 2014). Furthermore, increased microglial TLR2 expression was found in a subset of these affected brains (Doorn et al., 2014). Additional support for a role of TLR2-mediated inflammation in Parkinson's disease comes from Droiun-Ouellet et al., where TLR2 expression was increased in circulating monocytes of Parkinson's patients (Drouin-Ouellet et al., 2015). Therefore, this review aims to focus on the relationship between the particulars of αSyn and the TLR2 signaling pathway with respect to their roles in synucleinopathy progression and recent advances in inhibiting the microglial inflammatory response.

α-synuclein and the innate immune response of the CNS

The innate immune system is charged with differentiating between the self and other in order to maintain the health of the periphery and CNS. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are crucial in mediating host defenses to invading pathogens. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which include various bacterial and viral components, are the exogenous molecules that PRRs, such as RIG-I-like receptors, NOD-like receptors, and TLRs respond to (as reviewed by; Chen and Nunez, 2010).

Toll-like receptors

TLRs are named after the original gene that was identified in Drosophila and they are integral to the innate immune response. Thus far 13 mammalian TLRs have been identified, with humans expressing TLRs 1–10 and mice expressing TLR1-9 and 11–13. All 13 members are single pass transmembrane proteins with the C terminal located intracellularly and the N-terminal, which contains the distinctive leucine-rich repeats, situated extracellularly and acting as the ligand recognition domain (Matsushima et al., 2007). TLRs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 10 are located on the plasma membrane and recognize PAMPs from the extracellular space. In contrast, TLRs 3, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, and 13 are located on intracellular endosomes and are responsible for recognition of internalized PAMPs including both bacterial and parasitic DNA as well as viral single- and double-stranded RNA (as reviewed by; Akira et al., 2006; Kawai and Akira, 2007).

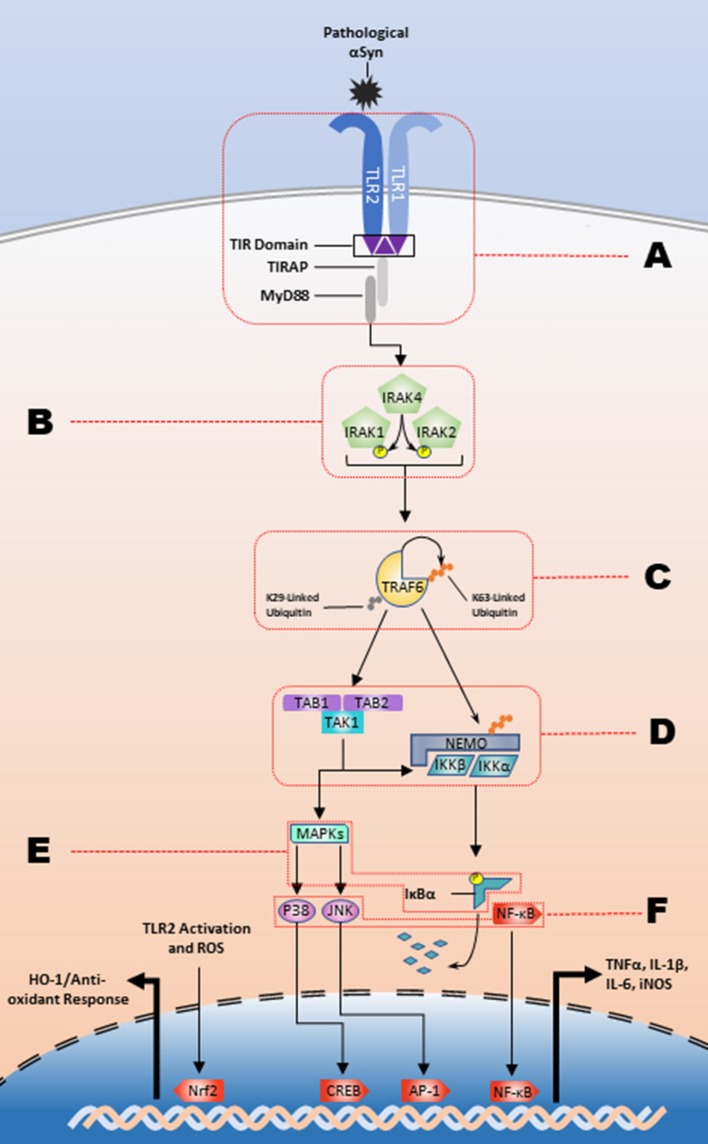

The inflammatory response is contingent upon the intracellular interactions of these signaling pathways. Intracellular C-terminal domains contain Toll-interleukin 1 receptor (TIR) domains, which are responsible for transforming extracellular recognition to an intracellular response (Xu et al., 2000; Horng et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2006). To date, 5 adaptor molecules have been identified that facilitate TLR signaling and lead to the differential cellular responses to varying stimuli: MyD88, TRIF, TRAM, TIRAP/Mal, and Sarm1. TRAM and TIRAP function to recruit MyD88 and TRIF to their respective TLRs and all TLRs, except for TLR3, activate the MyD88-dependent pathway (as reviewed by Kawai) (Horng et al., 2002; Kawai and Akira, 2010). The TRIF-dependent pathway signals through downstream kinases, TANK binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IKKε, to activate IRF3 and subsequently produce type 1 interferons (Yamamoto et al., 2002b; Oshiumi et al., 2003). In the MyD88-dependent pathway (Figure 1), death domain interactions mediate intracellular signal transduction in a sequential manner from MyD88 to the phosphorylation of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) 4, then to IRAK1 and IRAK2 (Lin et al., 2010). The IRAK complex interacts with TNF receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6) which will undergo K63-linked autoubiquitination and will ubiquitinate NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO). This is followed by the activation of the complex of transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1 (TAK1), TAK1 binding protein (TAB)2, and TAB3. TAK1 subsequently phosphorylates IKKα and IKKβ, and the IKKs will phosphorylate IκBα marking it for degradation. This ultimately results in production of proinflammatory cytokines through NF-κB, the heterodimeric p50/p65 protein, nuclear translocation and MAPK activation (as reviewed by) (Johnson and Lapadat, 2002; Symons et al., 2006; Kawai and Akira, 2007). As an example, the prototypical stimulator of this pathway, the TLR4 agonist bacterial-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Poltorak et al., 1998), causes an increase in the production of iNOS (Kacimi et al., 2011), and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL−1β, IL-6, and TNFα (Yamamoto et al., 2002a). However, several studies suggest that endogenous ligands, such as heparan sulfate, heat shock proteins, and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) can stimulate TLR signaling suggesting a role for sterile inflammation in diseases like synucleinopathies, which have the hallmark feature of increased amounts of misfolded endogenous proteins (Yu et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

The TLR2/1 signaling cascade and respective regulatory nodes. αSyn binding to the TLR2/1 heterodimer leads to a MyD88-dependent response that stimulates the kinase activity of the IRAK complex. The IRAK complex in turn activates TRAF6 K63-linked auto-ubiquitination, which subsequently leads to the release of the IKKs and activation of TAK1. The IKKs will designate IκBα for degradation and TAK1 will stimulate the MAPK pathway leading to the NF-κB, JNK, and p38 nuclear translocation to upregulate proinflammatory cytokines. There are several potential regulatory nodes and letters A-F represent those targets for intervention along the signaling pathway in order to impede pathogenesis.

α-synuclein: structure and function

αSyn is a pathogenic protein, which accumulates in all synucleinopathies and is hypothesized to propagate sterile inflammation in these disorders. TLRs, while recognizing foreign PAMPs, are also reactive to damage/danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). DAMPs, such as αSyn, are endogenous molecules that are intracellularly innocuous, but upon secretion or release following cellular injury will stimulate an innate immune response.

The primary function of αSyn under normal conditions has not been definitively described. However, αSyn is localized to axon terminals where it interacts with more than 50 other proteins and plays a role in vesicular transport. The protein is encoded by the gene SNCA that is located on chromosome 4 and evidence from SNCA knockout mice shows the loss of αSyn leads to hindered docked vesicle replenishment, which indicates a possible role for αSyn in vesicular trafficking between the reserve and readily releasable pools of neurotransmitter vesicles. Other potential in vivo functions for αSyn include enzymatic regulation, transporter regulation, mitochondrial function, and cell survival. Much support for the pathogenic role of αSyn comes from genetic mutations within SNCA that lead to familial cases of PD and evidence showing that triplication of wildtype SNCA leads to increased risk for development of PD. These data support a framework where both mutated αSyn and an overexpression of αSyn can be pathogenic (Singleton et al., 2003). Furthermore, evidence of αSyn-mediated inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and upregulation of dopamine transporters strengthens the case for the importance of αSyn in PD (as reviewed by; Dev et al., 2003; Uversky, 2007; Breydo et al., 2012; Lashuel et al., 2012; Deleersnijder et al., 2013).

αSyn is a 140 amino acid protein with a primary structure that can be divided into three domains. α-Helices compose the first 60 amino acids, the following 35 amino acids are largely hydrophobic, and the final 45 amino acids are acidic (Uversky, 2011b). The efforts to characterize the native conformation of αSyn have led to two proposals; one provides support for a stable tetramer formation that is ostensibly lost after cell lysis (Dettmer et al., 2013) and the other body of evidence shows αSyn to be an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) with an ill-defined secondary structure and a very compact tertiary structure (as reviewed by) (Uversky, 2011a; Breydo et al., 2012; Deleersnijder et al., 2013). Both of the above hypotheses are focused on the monomeric or low-molecular weight structure of αSyn, but it is not these species that seems to be driving the activation of TLRs.

Progression of misfolding and production of neurotoxic species

As mentioned above, αSyn is a presynaptic protein and thus Lewy body pathology is most often found in intraneuronal inclusions, except in multiple system atrophy where αSyn pathology is localized to oligodendrocytes. The ability for αSyn to have deleterious inflammatory effects on microglia originates from neuronal exocytosis, which was demonstrated in an in vitro αSyn overexpression model using SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Normal SH-SY5Y cell media has no effect on microglial proinflammatory production, but SH-SY5Y cells overproducing wildtype or A53T mutant αSyn induce the microglial proinflammatory response (Lee et al., 2010; Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011). In particular relevance to PD, greater protofibril αSyn stabilization occurred in the presence of dopamine (Conway et al., 2001). Furthermore, results from Xu et al. illustrate that αSyn-mediated neurotoxicity of substantia nigra dopamine neurons is due, in part, to αSyn interactions with dopamine synthesis that creates reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to neuronal death (Xu et al., 2002). While this corroborates a membrane-permeabilization/apoptotic hypothesis of disease pathogenesis, there is also evidence to suggest that neurons spontaneously exocytose vesicles rich in αSyn (Lee et al., 2005). This ER/Golgi-independent exocytotic mechanism is exacerbated under cellular stress conditions, such as proteasome inhibition (Jang et al., 2010). The extracellular αSyn can then be endocytosed by neighboring neurons and this neuron-to-neuron transmission has been shown to be neurotoxic (Desplats et al., 2009).

The process of αSyn aggregation and propagation is not conclusively understood. For example, the creation of high order oligomers can be initiated through a number of changes including the presence of metal ions, oxidative stress (Hashimoto et al., 1999), molecular crowding (Shtilerman et al., 2002), and environmental factors such as pesticides (Lai et al., 2002). During fibrillization the IDP nature of monomeric αSyn is converted to a β-sheet structure, which forms amyloid fibrils that are comparable to Aβ in Alzheimer's disease. These αSyn fibrils are composed of multiple proteins that stack in anti-parallel β-sheets, eventually becoming a primary constituent of Lewy bodies (Conway et al., 1998, 2000).

The intermediate steps that bridge the folding of a monomer to an amyloid fibril are potentially the most critical when considering the driving force behind synucleinopathies. Fibrillization occurs through the formation of partially folded intermediate structures that exist as membrane localized homodimers and annular structures (Ding et al., 2002; Tsigelny et al., 2008). The presence of polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are the major component of lipid membranes, enhance oligomer formation and have been found to be elevated in PD and DLB brains, compared to age-matched healthy controls (Perrin et al., 2001; Sharon et al., 2003). There is also evidence to suggest that pathological phosphorylation at Ser-129 of αSyn potentiates the fibrilization process (Fujiwara et al., 2002). Interestingly, evidence suggests that it is these oligomeric structures, and not the fibrils, that are neurotoxic due to an increase in membrane permeabilization (Volles et al., 2001; Volles and Lansbury, 2002). Karpinar et al. generated a number of αSyn variants with proline residue substitutions in three different locations of the primary amino acid sequence. The mutants were much less likely to form highly organized fibrils and were more toxic than wildtype αSyn samples due to the increase in protofibril structures. Furthermore, in Drosophila, these mutations led to a reduction of TH+ cells in the lateral and medial brain fractions (Karpinar et al., 2009). Multiple reports show that it is high molecular weight αSyn and not monomeric conformer, that leads to microglia activation and TNFα release (Su et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010; Béraud et al., 2013; Fellner et al., 2013; Daniele et al., 2015). However, contradictory evidence from a THP-1 cell model demonstrates fibrils, and not monomers or oligomers of αSyn, are able to generate an inflammatory response (Gustot et al., 2015). It should be noted that αSyn treatment conditions vary between laboratories and may be the reason for disparate experimental outcomes. Furthermore, the folding mechanisms are difficult to assess in vivo (Danzer et al., 2007).

Microglial and neuronal expression of TLR2/1

TLR2 is a member of the MyD88-dependent receptor family that is associated with a diverse set of ligands. TLR2 interacts with peptidoglycan, Gram-positive bacteria, lipoproteins, and the yeast cell wall component zymosan (Underhill et al., 1999a,b; Ozinsky et al., 2000; Takeuchi et al., 2000, 2002; Morr et al., 2002). In order to associate with and recognize these various agonists TLR2 requires a coreceptor, typically TLR1 or TLR6. The TLR2/1 heterodimer is activated by Pam3CSK4, a synthetic tri-acylated lipopeptide, highlighting the specificity for tri-acylated lipoproteins (Ozinsky et al., 2000; Takeuchi et al., 2001, 2002; Buwitt-Beckmann et al., 2006). TLR2 activity is also implicated in non-immune functions, such as the potential to regulate metabolism and protect against age-related obesity (Shechter et al., 2013).

Within the cell, TLR2 and TLR1 colocalize with one another both intracellularly and on the plasma membrane, demonstrating that the two receptors are potentially in their heterodimeric state prior to any ligand interaction. Sandor et al. used chimeric TLR2 and TLR1 proteins to investigate each receptor's role in NF-κB translocation and found both intracellular TIR domains were needed to recruit MyD88 and propagate a signal (Sandor et al., 2003). Upon binding of Pam3CSK4, TLR2/1 adopts an “m” shaped conformation with the two C-terminal domains interacting in the interior intracellular region and each N-terminal arching out extracellularly. The Pam3CSK4 binding domain is found at the pocket formed between the central and C-terminal domains, a convex region which is atypical for the leucine rich receptor family (Jin et al., 2007). It is postulated that there are hydrophobic portions of TLR2/1 that could be involved in large DAMP recognition (Nishiguchi et al., 2001; Okusawa et al., 2004; Jin et al., 2007). Liang et al. demonstrated that the pentameric B subunit of type IIb (LT-IIb-B), a doughnut shaped oligomeric protein from E. coli, had 10 potential binding sites on TLR2/1. The convex region of TLR2 is postulated as the most likely region where LT-IIb-B binds (Liang et al., 2009).

A growing body of evidence establishes a role for TLRs expressed on microglia to mediate cell death in the neural environment. For example, stimulation of TLR4 leads to a loss of oligodendrocytes and axons that is not seen when microglia are absent (Lehnardt et al., 2003). TLRs also play an important role in pain (as reviewed by; Nicotra et al., 2012). Tanga et al. demonstrated that TLR4 contributes to early neuropathic pain associated with nerve transection suggesting that while these receptors are conserved mediators of pathogen recognition and removal, TLRs also have the potential to accelerate neurodegeneration upon activation (Tanga et al., 2005). Similarly, TLR2 (Jana et al., 2008), TLR4, and CD14 are implicated in Alzheimer's disease as integral receptors for fibrillar Aβ recognition (Reed-Geaghan et al., 2009). Within the field of synucleinopathy research, oligomeric forms of αSyn have been shown to directly interact with the TLR2/1 heterodimer and lead to a prototypical inflammatory response (Kim et al., 2013, 2015; Daniele et al., 2015). Other reports support a role for TLR4 in αSyn recognition, where this ligand-receptor interaction facilitates a phagocytic response (Stefanova et al., 2011). Taken together, the above investigations support that αSyn binds to TLR MyD88 family members and in the case of TLR2/1 this interaction may occur in a similar fashion as LT-IIb-B, resulting in activation of this heterodimeric receptor on microglia and contributing to pathogenesis. These studies provide rationale supporting the hypothesis that the oligomeric, and not monomeric, species of αSyn are responsible for disease pathology.

In microglia

Microglia reside in the CNS and function as the resident immune cells of their local environments. Morphologically, inactive microglia are filamentous, continually extending and retracting processes surveying their surroundings (Davalos et al., 2005; Nimmerjahn et al., 2005). Microglia possess the capacity for recognition of various pathogens and endogenous cues, which produce further morphological changes that are typically described as the M1 or M2 phenotypes (de Sousa et al., 2011; Wei et al., 2011). This binary categorization is meant to represent the prototypical proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory/phagocytic responses of microglia (Bachstetter et al., 2014; Majerova et al., 2014). But more recent investigation has begun to reorganize this nomenclature in favor of a continuum of morphological characteristics, each of which being representative of a particular microglial function (as reviewed by; Hanisch, 2013; Kim C. C. et al., 2016; Morganti et al., 2016; Ransohoff, 2016). The heterogeneity of phenotypes is further evidenced by age and region specific analyses that show the great diversity of microglia (Grabert et al., 2016).

TLRs are integral to microglia, and the microglial expression of the TLR2/1 heterodimer is specifically implicated in synucleinopathy pathogenesis. αSyn or Pam3CSK4 activation of TLR2 in BV-2 microglia (Béraud et al., 2013), primary mouse microglia (Babcock et al., 2006; Downer et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Daniele et al., 2015), and human microglia leads to the MyD88-dependent release of TNF-α and IL-1β (Dzamko et al., 2016). Following stimulation of TLR2/1, TLR2 mRNA and protein are increased in microglia (Syed et al., 2007). Studies such as this provide rationale for a cyclical process of inflammation, where once an initial insult is recognized the microglia are primed for sustained proinflammatory responses. Further investigation shows that αSyn overexpressing SH-SY5Y cells release oligomeric αSyn, the SH-SY5Y conditioned media is capable of activating microglia, and microglia TLR2 expression is required for this activation (Kim et al., 2013; Kim C. et al., 2016). The activation profile of microglia exists somewhere within the spectrum of the prototypical M1 and M2 states when pretreated with non-aggregated αSyn and subsequently activated with Pam3CSK4 (Roodveldt et al., 2013), supporting the dynamic phenotype model of microglia and suggesting that in vivo microglial activation via oligomeric αSyn could result in paracrine/autocrine TNF-α signaling that potentiates microgliosis and neuronal death.

The microglial response via TLR2/1 is not a homogenous proinflammatory response. Rather, 24 h after αSyn stimulation microglia also produce IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine (Daniele et al., 2015). The endogenous Ras-ERK inhibitors, downstream of kinase (Dok) 1 and 2, are also upregulated in microglia following TLR2/1 stimulation. While ERK phosphorylation is also increased after TLR2 activation, the upregulation of Dok1 and Dok2 represent another inhibitory signal that is upregulated to limit the immediate inflammatory response of microglia (Downer et al., 2013). There is also an antagonistic pathway mediated by the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/antioxidant response element (ARE) pathway, which transcriptionally upregulates heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) in the CNS as well as the periphery (Lee and Suk, 2007; Koh et al., 2011). The proinflammatory response from microglia generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), which in turn stimulates the Nrf2/ARE pathway as a late phase response to control microglial activation (Li et al., 2008; Innamorato et al., 2009). The Nrf2/ARE and the NF-κB pathways cross regulate one another, which provides a unique target for managing microglial responses to αSyn and proinflammatory cytokines (Innamorato et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2008).

In neurons

Neurons themselves are also capable of expressing TLRs. Evidence suggests that TLRs play a role in neuronal morphogenesis, neurodegeneration, and cytokine production (as reviewed by) (Liu H. Y. et al., 2014). TLR2 is expressed in NT2-N teratocarcinoma cells (Lafon et al., 2006), SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell (Kim et al., 2015), primary mouse neurons (Downer et al., 2013), and human neurons in the CNS (Dzamko et al., 2016) and ENS (Brun et al., 2013). Very interestingly, Dzamko et al. surveyed 17 human PD brains and found a statistically significantly age-related increased in neuronal TLR2 expression (Dzamko et al., 2016). One group showed that neuronal transmission of αSyn can be mediated by lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), which binds to αSyn fibrils during neuronal endocytosis (Mao et al., 2016). Both SH-SY5Y and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons amass αSyn after Pam3CSK4 but not LPS treatment, suggesting neuronal TLR2/1 stimulation upregulates αSyn expression and/or accumulation in neurons (Dzamko et al., 2016). Together these studies suggest that αSyn can act in a paracrine/autocrine fashion to activate both microglial and neuronal TLR2/1 in order to potentiate microglial activation and neuronal degeneration.

While neurons can express and release proinflammatory cytokines, some evidence suggests that the primary effect of αSyn-mediated TLR2/1 signaling is through an inhibition of the autophagy pathway. Kim et al. demonstrate TLR2 signaling increases mTOR and Akt phosphorylation, which impairs the autophagy (Kim et al., 2015). The Akt phosphorylation may be mediated by TRAF6 K63-linked ubiquitination (Yang et al., 2009). When assessing potential causes for neuronal loss, this evidence provides insight into potential mechanisms of αSyn-related neuronal autophagocytotic dysregulation that could contribute to synucleinopathy pathology. In this setting, impaired autophagy would lead to an accumulation and release of neuronal αSyn making this protein available as an endogenous TLR ligand.

Inhibiting the inflammatory pathway

As the evidence supporting a pathological role for TLR2/1 signaling pathway has increased, there has been a heightened interest in discovering potential avenues to modulate this pathway for therapeutic benefits. The interdisciplinary findings from both neuroscience and immunology have helped provide supporting data and novel ways to treat synucleinopathies. The spectrum of potential interventions to inhibit the various nodes of the pathway is depicted in Figure 1 and includes modulation of endogenous microRNA's and proteins, as well as treatment with both naturally derived, and synthetic compounds, described in Table 1, for the purpose of treating diseases characterized by inflammatory environments.

Table 1.

Modulators of the TLR2/1 signaling pathway.

| Inhibitor | Target | References |

|---|---|---|

| MicroRNAs | ||

| miR-UL112-3p | TLR2 | Vo et al., 2005 |

| miR-K5 | IRAK1 | Xiao and Rajewsky, 2009 |

| miR-K9 | MyD88 | Xiao and Rajewsky, 2009 |

| miR-143 | TLR2 and NF-κB | Krichevsky et al., 2003; Wayman et al., 2008 |

| miR-132 | IRAK4 | Abend et al., 2012 |

| miR-21 | MyD88 and IRAK1 | O'Neill et al., 2011 |

| miR-146a | TRAF6 and IRAK1 | Chen et al., 2013a; Guo et al., 2013; Landais et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015 |

| miR-124 | TRAF6 | Taganov et al., 2006; Nahid et al., 2013 |

| miR-92a | MKK4 | Meisgen et al., 2014 |

| miR-147 miR-7116-5p | Unknown TNFα | Saba et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2014; Santra et al., 2014 |

| miR-155 | SOCS1 and SHIP1 | Liu et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2016 |

| NATURAL COMPOUNDS | ||

| Methylpenicinoline | Unknown | Strassheim et al., 2005 |

| Calcitriol | miR-155 | Nakagawa et al., 2002 |

| Schizandrin A/B | Unknown | Aravalli et al., 2008; Aslanidis et al., 2015; Koymans et al., 2015 |

| Gomosins A/G/J/N Pristimerin | Nrf2 IRAK1 and TRAF6 | Chen et al., 2013b; Kim et al., 2014 |

| Deoxysappone B | Unknown | Song et al., 2016 |

| Sparstolonin B | MyD88 | Park et al., 2014 |

| Daphnetin | A20 | Kumar et al., 2016 |

| Curcurbitacin B/E/I | Nrf2 | Liu et al., 2016 |

| Kolaviron | Nrf2 | Yao et al., 2011 |

| Pseudoginsenoside-F11 | MyD88 | Park et al., 2015 |

| SYNTHETIC COMPOUNDS | ||

| CU-CPT22 | TLR2/1 | Arel-Dubeau et al., 2015; Olajide et al., 2017 |

| RSCL-0409 | MyD88 | Oyagbemi et al., 2017 |

| C16H15NO4 (C29) | MyD88 | Wang et al., 2014 |

| Ortho-vanillin | MyD88 | Wang et al., 2014 |

| M2000 | Unknown | Kalluri et al., 2010; Mistry et al., 2015 |

| G2013 | Unknown/Tollip | Afraei et al., 2015; Mirshafiey et al., 2016; Aletaha et al., 2017 |

| NG25 | TAK1 | Pourgholi et al., 2017 |

| MRT67307 | TBK1 and IKKε | Jahromi et al., 2017 |

| BMS345541 | IKKβ | Nazeri et al., 2017 |

| MCAP | Unknown | Hajivalili et al., 2016 |

| Bay-11-708 | NF-κB | Sharifi et al., 2017 |

| Candesartan | Angiotensin II receptor | Pauls et al., 2012 |

| Fasudil | Rho kinase | Yang et al., 2006; Clark et al., 2011 |

| cRGD | MFG-E8 receptor | Matteucci et al., 2015 |

microRNA regulation

microRNAs are a class of non-coding RNAs that are approximately 23 nucleotides in length. They act as translational repressors (Baek et al., 2008) and are involved in development (Wightman et al., 1991, 1993; Vo et al., 2005), neurogenesis (Krichevsky et al., 2003), and plasticity (Wayman et al., 2008). These small regulatory microRNA's are also instrumental in the endogenous regulation of the immune system and specifically TLR signaling (as reviewed by; Xiao and Rajewsky, 2009; O'Neill et al., 2011).

The membrane localized site of node A (Figure 1) is a target for multiple microRNAs. The exogenous miR-UL112-3p, a product of the human cytomegalovirus, directly binds the 3' untranslated region of TLR2 (Landais et al., 2015). The endogenous miR-143 downregulates TLR2 in hepatoma cells (Liu et al., 2015) and colorectal carcinoma cells (Guo et al., 2013). The receptor-adaptor complex is also known to be regulated at MyD88 by miR-21 (Chen et al., 2013a) and miR-K9, which is a product of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (Abend et al., 2012).

A larger collection of microRNAs has been identified that have inhibitory effects on TLR2 signaling (Figure 1; Node B). IRAK1 is targeted by miR-K5 (Abend et al., 2012), again from Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, miR-21 (Chen et al., 2013a) and miR-146a (Taganov et al., 2006; Nahid et al., 2009, 2011; Quinn et al., 2013). Additionally, IRAK4 is inhibited by the TLR2-upregulated and CREB-dependent miR-132 in THP-1 cells, human PBMCs, and murine microglia (Nahid et al., 2013). Further along the signaling pathway (Figure 1; Node C) the auto-ubiquitinating TRAF6 has been intensely investigated with relation to THP-1 cells (Taganov et al., 2006; Nahid et al., 2011; Quinn et al., 2013), keratinocytes (Meisgen et al., 2014), PBMCs (Nahid et al., 2013), oligodendrocytes (Santra et al., 2014), and microglia using TLR2, TLR4, and prion-induced mechanisms (Saba et al., 2012). miR-146a inhibits the translation of TRAF6, while miR-146a knockdown leads to an increased production of proinflammatory cytokines. TRAF6 is also a target of miR-124, which inhibits the inflammatory response (Ma et al., 2014; Qiu et al., 2015). Activation of TLR2, or stimulation via the actin regulator thymosin β4, leads to the subsequent upregulation of miR-146a that lasts up to 4 days post-stimulation, which signifies the robust endogenous response following TLR2 activation that is created to modulate the inflammatory response (Meisgen et al., 2014; Santra et al., 2014). There is also microRNA inhibition at node E (Figure 1) that indicates additional layers of endogenous regulation of the TLR2 activation pathway. Overexpression of miR-92a inhibits TNFα and IL-6 release through inhibition of MKK4, a MAPK family protein, and is downregulated following TLR2 stimulation (Lai et al., 2013). A recent study has also identified miR-7116-5p as a negative regulator of TNFα protein production and the MPTP model of PD leads to a downregulation of miR-7116-5p (He et al., 2017).

It is also important to note that not all TLR-associated microRNAs have known functions or downregulate the pathway. The target of miR-147 is unknown, but miR-147 is upregulated following TLR2 and TLR4 stimulation and reduces proinflammatory cytokine production (Liu et al., 2009). Further investigation has shown miR-147 suppresses Akt expression in breast cancer cell lines (Zhang et al., 2016). These data suggest a possible complimentary mechanism for miR-147 where it may be able to limit the proinflammatory response, but it could also be promoting the autophagy pathway. A prototypical example of TLR2 signaling potentiation is miR-155, which is upregulated with TLR4 activation via both the AP-1 (O'Connell et al., 2007; Yin et al., 2008) and NF-κB pathways (Bala et al., 2011). miR-155 increases the production of TNFα and other cytokines through its inhibition of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) (Cardoso et al., 2012) and Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase 1 (SHIP1) (Thounaojam et al., 2014).

The manipulation of microRNAs as a therapeutic strategy is a unique and interesting approach to modifying synucleinopathy pathogenesis. Exogenous viral microRNAs are likely used in order for the viruses to invade the host immune system and the properties of miR-UL112-3p, miR-K5, and miR-K9 could be exploited for therapeutic effects. But it is also important to note that Jurkin et al. demonstrated alternative expression profiles of miR-146a in different cell types (Jurkin et al., 2010). This indicates the need for a more complete understanding of how each microRNA functions within the CNS prior to the development of synucleinopathy therapies.

Endogenous proteins

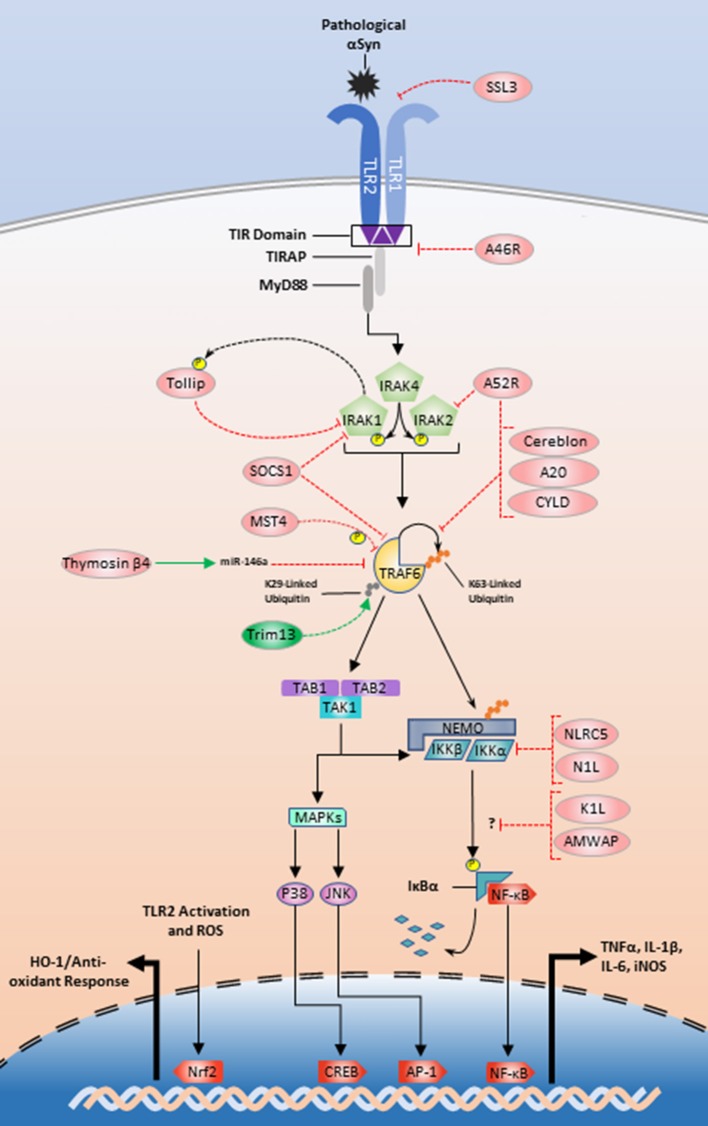

Continuing efforts to manipulate the TLR2/1 inflammatory pathway also utilize endogenous-protein regulators in conjunction with microRNAs. As mentioned above, thymosin β4 is an example of an endogenous protein that promotes miR-146a upregulation and subsequent TRAF6 and IRAK1 translational repression (Santra et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2015). IRAK1 is also regulated by Tollip, which is a substrate for IRAK1 phosphorylation that interacts in a negative feedback loop (Figure 2), to inhibit IRAK1 and limit the production of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Zhang and Ghosh, 2002; Didierlaurent et al., 2006; Shah et al., 2012). Interestingly, Tollip is highly expressed within the midbrain region of mice, making it a high priority target in relation to PD (Humbert-Claude et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Exogenous and endogenous protein regulation of the TLR2/1 signaling pathway. Initial regulation could begin with SSL3 inhibition of αSyn recognition or A46R disturbance of the MyD88-TIR interface (Node A; Figure 1). Tollip, A52 and SOCS1 could be manipulated to inhibit signaling at the IRAK complex (Node B; Figure 1). TRAF6 inhibition could be achieved by interference with Trim13 or positive modulation of SOCS1, MST4, thymosin β4, cereblon, A52R, A20, and CYLD (Node C; Figure 1). Lastly NLRC5 and N1L could be positively upregulated to inhibit the IKKs (Node D; Figure 1). The modes of action for K1L and AMWAP are not established, but these two proteins along with upregulation of the transcription factor Nrf2 are also potential targets for TLR2/1 modulation.

TRAF6 is also an emerging target for TLR modulation and looks to be tightly and multiply regulated (Figure 2). A large structural analysis study identified two de-ubiquitinases, A20 and CYLD, as endogenous regulators of TRAF6 K63-linked ubiquitin chains (Guven-Maiorov et al., 2015). Using a THP-1 model, Jiao et al. showed that MST4 directly phosphorylates TRAF6 and MST4 upregulation reduces proinflammatory cytokine release (Jiao et al., 2015). Cereblon and Nod-like receptor C5 (NLRC5) interact with TRAF6 in contradictory fashions. Cereblon functions as a ubiquitin inhibitor by disturbing the TRAF6 zinc-finger ubiquitination domain (Min et al., 2016). NLRC5 is an endogenous regulator of the IKK complex and limits NF-κB translocation, but upon LPS stimulation NLRC5 is ubiquitinated by TRAF6. This suggests a secondary role for TRAF6 where it communicates outside of the paradigmatic inflammatory pathway to turn off regulators of downstream TLR signaling kinases (Cui et al., 2010; Meng et al., 2015). Furthermore, a recent study implicates the E3 ubiquitin ligase tripartite motif family 13 (Trim13) as a potentiator of TRAF6 ubiquitination and function. Trim13 knockdown inhibits TRAF6 K29-linked ubiquitination and NF-κB signaling more generally (Huang and Baek, 2017).

There are also several other proteins that may be important targets for TLR2 signaling modulation. Evidence suggests SHIP1 inhibits TBK1, a member of the TRIF-dependent signaling pathway (Gabhann et al., 2010; Thounaojam et al., 2014). Neutrophils derived from SHIP1−/− mice are more susceptible to TLR2-mediated cytokine production as well as increased Akt activation (Strassheim et al., 2005). This result suggests that enhancing SHIP1 activity may reduce the proinflammatory response and reduce the ability for autophagy. SOCS1 also plays an inhibitory role restricting cytokine production through interactions with IRAK1 or TRAF6 (Nakagawa et al., 2002; West et al., 2006; Cardoso et al., 2012). Another possible therapeutic target is activated microglia/macrophage whey acidic protein (AMWAP), which is produced and released by microglia in neurotoxic conditions. Pretreatment of microglia with AMWAP prior to TLR2 stimulation reduces the mRNA expression of IL-6, iNOS, and TNFα, but the exact inhibitory interaction that prevents IκBα degradation is unclear (Aslanidis et al., 2015).

Naturally occurring compounds

The identification and use of naturally occurring proteins and compounds has also proven fruitful in limiting inflammatory responses. Staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 3 (SSL3) is a product of Staphylococcus aureus that is used to evade the immune system through TLR2/1 dimer inhibition (Koymans et al., 2015). Further investigation with vaccinia virus proteins shows that A46R inhibits multiple TLR-adaptor interactions and A52R inhibits both TRAF6 and IRAK2. K1L and N1L are two additional vaccinia virus proteins that inhibit IκBα degradation and the downstream kinases TBK1 and IKKs respectively (Aravalli et al., 2008). These exogenous proteins, along with above endogenous protein regulators are shown in Figure 2. Other fungal products such as methylpenicinoline from Penicillium sp. (SF-5995) reduces both NF-κB translocation and the JNK-dependent signaling in BV2 microglia (Kim et al., 2014). Calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D, represses miR-155 after LPS stimulation and reduces NF-κB nuclear translocation (Chen et al., 2013b).

Plant-derived therapeutic compounds are among the most abundant in anti-inflammatory research. Multiple lignans and lignins suppress inflammation induced by TLR2- and TLR4-mediated pathways. These bioactive compounds are found in the Chinese medicinal plant Schisandra chinensis and are part of the dibenzocyclooctadiene family; schizandrin A (Song et al., 2016), schizandrin B (Giridharan et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2012), and gomosins A/G/J/N inhibit microglial production of NO, TNFα, and IL-6. The gomosins act by increasing Nrf2 translocation and downregulating the MAPK pathways (Park et al., 2014). Pristimerin, an extract from Tripterygium wildi, reduces the release of NO and suppresses the protein and mRNA production of TNFα and IL-6 in BV2 microglia stimulated with LPS by inhibiting the IRAK1-TRAF6 interaction (Hui et al., 2018).

Various other herbal Chinese compounds also have potential for treating the neuroinflammatory response in synucleinopathies and their targets are listed in Table 1. The Chinese plant Caesalpinia sappan produces deoxysappone B, which inhibits the NF-κB and MAPK pathways and also reduces in vitro neuronal death in neuron-microglia cocultures (Zeng et al., 2015). Sparstolonin B is a product from Sparganium stoloniferum and it reduces IL-6 expression in a myocardial hypoxia model (Liu Q. et al., 2014) as well as TNFα following TLR2 stimulation in both RAW264.7 (Liang et al., 2015) and THP-1 cells by preventing the TLR2/1-MyD88 interaction (Liang et al., 2011). Lastly, a member of the coumarin family isolated from Daphne odora, named Daphnetin, decreases IL-6, TNFα, IL-1β, and NF-κB in models of anti-angiogenesis (Kumar et al., 2016), cerebral infarction (Liu et al., 2016), severe acute pancreatitis (Liu Z. Y. et al., 2014), and arthritis (Yao et al., 2011; Tu et al., 2012). One potential mode of action for Daphnetin may be through upregulation of A20, which modulates TRAF6 activity (Figure 2; Yu et al., 2014).

The Cucurbitaceae genus produces a number of compounds including cucurbitacins B, E, and I that reduce IL-6, TNFα, and IL-1β in microglia as well as induce Nrf2 nuclear translocation (Park et al., 2015). Cucurbitacin E also protects differentiated PC12 neurons from a PD model of MPTP-induced neurotoxicity (Arel-Dubeau et al., 2015). Similarly, kolaviron from the Garcinia kola plant, activates the Nrf2/ARE pathway and inhibits the release of IL-6 and TNFα in BV2 microglia following TLR4 stimulation (Onasanwo et al., 2016). Kolaviron is also neuroprotective and cardioprotective in rat models of oxidative stress (Olajide et al., 2017; Oyagbemi et al., 2017). In both in vitro and in vivo studies, Wang et al. demonstrate that pseudo-ginsenoside F11, derived from American ginseng, reduces microglial release of proinflammatory cytokines, inhibits Akt phosphorylation, and protects against neuronal death (Wang et al., 2014).

Synthetic agents

The most diverse and robust class of TLR signaling inhibitors is the group of synthetic compounds found in Table 1. Starting at the origin of the signaling pathway, CU-CPT22 is known to be a TLR2/1 heterodimer antagonist with the ability to inhibit TLR2-mediated proinflammatory induction (Cheng et al., 2012; Daniele et al., 2015; Bock et al., 2016; Su et al., 2017). RSCL-0409, a gluco-disacharide, reduces TLR2 and TLR4 mediated TNFα release potentially through disruption of the TIR-adapter interaction, but the exact mechanism is not known (Kalluri et al., 2010). Similarly, C16H15NO4 (C29) and ortho-vanillin both block TLR2/1 signaling in murine macrophages via disruption of the MyD88 interaction with the TIR domain (Mistry et al., 2015). β-D-mannuronic acid (M2000) and its analog α-l-guluronic acid (G2013) are novel non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) currently being studied. In relation to oxidative stress, M2000 and G2013 non-significantly increase regulatory enzymes related to oxidative stress, but investigation of these two NSAIDs should not be immediately abandoned (Afraei et al., 2015; Mirshafiey et al., 2016; Hosseini et al., 2017). The mode of action for M2000 has been postulated as both a TLR2/TLR4 antagonist (Aletaha et al., 2017) and a miR-155 inhibitor (Pourgholi et al., 2017). Further investigations demonstrate M2000's ability to significantly decrease miR-146a, TRAF6, IRAK1, and NF-κB mRNA (Jahromi et al., 2017). These data indicate that oxidative stress markers may be the wrong outcome variables to assess the efficacy of these two NSAIDs and mediators of inflammation such as TLR2/1 signaling intermediates and the proinflammatory cytokines should be used instead. G2013 also appears to inhibit IRAK1/TRAF6 without modulation of miR-146a (Hajivalili et al., 2016; Nazeri et al., 2017), which could occur through regulation of Tollip mRNA transcript levels. The data indicates a high dose of G2013 lowers Tollip mRNA while also reducing NF-κB and IL-1β mRNA, which is counterintuitive with respect to the understanding of how Tollip functions as a negative regulator of IRAK1, and necessitates further investigation (Figure 2; Sharifi et al., 2017).

Many inhibitors target the cytosolic signaling proteins much like microRNA's. Dzamko et al. used a panel of inhibitors such as NG25, MRT67307, and BMS345541 which target TAK1 (Pauls et al., 2012), IKKε (Clark et al., 2011), and IKKβ respectively (Yang et al., 2006). All four successfully limit TLR2-mediated αSyn accumulation after TLR2 stimulation in SH-SY5Y cells, which demonstrates the efficacy of modulating the TLR2 pathway in both neurons and microglia (Dzamko et al., 2016). Another compound, MCAP, can inhibit IκBα phosphorylation and in turn reduce proinflammatory mRNA upregulation (Kim B.-W. et al., 2016). Lastly, Bay-11-708 a known inhibitor of NF-κB has been used to attenuate inflammation (Chen et al., 2013b; Matteucci et al., 2015).

Aside from direct inhibition of the TLR2 signaling pathway, there is also evidence supporting secondary roles for existing drugs and phagocytic inhibitors. The sartans are one such drug family that were first identified as angiotensin II receptor inhibitors. In a human monocyte model, candesartan downregulates TLR2 protein and mRNA, while also inhibiting NF-κB activation (Dasu et al., 2009). These results have been confirmed in primary microglia where candesartan reduced αSyn-mediated TNFα release (Daniele et al., 2015). Another drug, fasudil, which is a Rho kinase inhibitor, decreases TNFα and IL-1β, upregulates anti-oxidant/inflammatory molecules, Nrf2 and IL-10 (Liu et al., 2013; Zhao Y. F. et al., 2015), and protects TH+ neurons in vivo in a MPTP-model of PD (Li et al., 2017). And in an alternative approach to microglial inhibition, cyclic Arginine-Guanine-Aspartic Acid (cRGD), has been used to repress autophagy, which in turn reduces neuronal loss when co-cultured with TLR2-activated microglia (Neher et al., 2011). In vivo injection of cRGD reduced microglial-mediated neuronal phagocytosis in a mouse model of retinal degeneration (Zhao L. et al., 2015). These cRGD studies are intriguing insofar as they complicate the use of Akt as a therapeutic target. As discussed earlier, TLR2 activation and subsequent inhibition of Akt in neuronal cultures protected against cell death, but Neher et al. demonstrate TLR2 activation in conjunction with cRGD-mediated phagocytic inhibition protects neurons. This could be due to independent phagocytic pathways in microglia and neurons and we believe this necessitates further investigation.

All the above studies, and their respective drugs and targets (Table 1), provide a glimpse into the potential for discovering the next best course of treatment for synucleinopathies. Not all of the studies discussed have been verified in microglial models or more importantly in vivo models of disease. Further investigations and critical analyses of the mechanism of action for each potential inhibitor within the CNS are required before moving forward. We believe it is important to examine the potential choices available for TLR2 modulation—both the intended and potential unintended effects. For example, while antagonists of MyD88 signaling are available, the effects of inhibiting this widely used adaptor protein may prove to be a dangerous method for curtailing the microgliosis and neuroinflammation in vivo. Thus, we suggest a focus on the downstream effector proteins from the IRAKs to the IKKs as well as the Nrf2 and autophagocytic pathways in order to manage the proinflammatory response in synucleinopathies.

Clinical trials and future therapeutics

The current landscape of clinical trial data is relatively small with regards to synucleinopathies and potential treatments involving modulation of microglia and the inflammatory response. While major therapeutics have not been discovered for treatments of synucleinopathies in humans, there have been advancements in characterization of neural inflammation. The peripheral benzodiazepine receptors (PBRs) are expressed on activated microglia and the PET PBR ligand [11C](R)-PK11195 provides a method for tracing microglial activation in patients. This diagnostic procedure has been validated multiple times (Gerhard et al., 2004, 2006a,b), and Ouchi et al. demonstrated that [11C](R)-PK11195 binding potential (BP) is inversely correlated with the dopamine transporter marker [11C]-CFT BP in the putamen (Ouchi et al., 2005). It is also interesting to note that that another group using [11C](R)-PK11195 PET described an inability to use the cerebellum as a BP control region, as has been done in Alzheimer's disease studies, and propose the need for more specific PBR tracers for synucleinopathies (Bartels et al., 2010). There is also an active clinical trial (NCT02702102) that is investigating the efficacy of [11C](R)-PBR28 as an alternative measure of microglial activation in DLB and PD with dementia (Kreisl et al., 2017).

Investigations into the use of NSAIDs and aspirin in neurodegenerative diseases initially seemed fruitful (Klegeris and McGeer, 2005). An epidemiological study demonstrated a decreased relative risk of developing PD if an individual took aspirin twice daily or regularly used NSAIDs on a weekly basis (Chen et al., 2003). The Bartels et al. study demonstrated the inefficacy of celecoxib in reducing microglial activation in PD patients (Bartels et al., 2010) and implementation of NSAIDs or rofecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, did not have any significant influence on AD progression (Aisen et al., 2003). Since both AD and PD are progressive and patients present with varying epigenetic and genetic backgrounds, the failure of these clinical trials could be due to the patient population selected. There has been a phase I/II trial for M2000 to assess the efficacy of this novel NSAID compared naproxen for ankylosing spondylitis. The therapeutic benefits was no different than naproxen, but M2000 did have fewer adverse effects that could make this drug more attractive for future PD related trials (Fattahi et al., 2017).

A number of clinical trials have attempted to modify disease pathogenesis or target the extracellular receptors, but few have been successful. For example, CEP-1347 is a JNK inhibitor used in early-stage PD patients in an attempt to enhance neuronal survival, but CEP-1347 had no effect in delaying the onset of more severe symptoms that required dopamine therapy (Wang et al., 2008). Further clinical studies using TLR4 antagonists, TAK-242 (Rice et al., 2010) and eritoran (E5564) (Bennett-Guerrero et al., 2007), both failed to significantly change cytokine levels or post-operative outcomes respectively, despite pre-clinical successes (Rossignol and Lynn, 2002; Ii et al., 2006). The failure of these two drugs may present a harbinger for the potential ineffectiveness of directly targeting the ligand binding domain of TLR2/1. Despite these failures ibudilast, an inhibitor of microglial activation via phosphodiesterase inhibition, shows significant effects in reducing the Subjective Opioid Withdrawal Scale scores of heroin users after ending daily heroin use (Cooper et al., 2016). A drug of this nature although separate from direct TLR2 pathway intervention could be a potential target for PD therapy, particularly in early stages of the diseases when microglial activation is accelerating but symptoms are not severe.

Conclusions

The current body of literature surrounding the function and modulation of inflammation is continually growing and emphasizes how inflammation potentiates multiple disease states. The results described herein provide insight into the many ways inflammatory processes may result in continued neurodegeneration. While the disease initiating events in relation to synucleinopathies and other neurodegenerative diseases are still debated, it seems likely that the cyclicity of microglial activation and continued propagation of a proinflammatory neural environment is integral to the neuron loss that leads to the most severe synucleinopathy symptoms.

As previously discussed, there is reason to expect that not all findings from peripheral model systems will directly translate to studies of the CNS. But for some of the aforementioned compounds there is strong evidence to support their efficacy in vitro and in animal models, which may be translatable to human synucleinopathy patients. And for those strategies that are not immediately ready for clinical trials, such as microRNA or protein activity manipulation, there are now numerous avenues to investigate novel strategies to regulate these compounds in an effort to combat inflammation and microgliosis. The sheer wealth of possibilities brings hope toward finding successful pharmacological interventions to limit or even stop the disease progression of synucleinopathies.

Author contributions

IC and KM-Z wrote this review. IC wrote the initial draft and prepared all the figures for this review.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported in part by the Georgetown Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (IC) and NIH/NINDS R01NS083410 (KM-Z).

References

- Abend J. R., Ramalingam D., Kieffer-Kwon P., Uldrick T. S., Yarchoan R., Ziegelbauer J. M. (2012). Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNAs target IRAK1 and MYD88, two components of the toll-like receptor/interleukin-1R signaling cascade, to reduce inflammatory-cytokine expression. J. Virol. 86, 11663–11674. 10.1128/JVI.01147-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afraei S., Azizi G., Zargar S. J., Sedaghat R., Mirshafiey A. (2015). New therapeutic approach by G2013 in experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Belg. 115, 259–266. 10.1007/s13760-014-0392-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aisen P. S., Schafer K. A., Grundman M., Pfeiffer E., Sano M., Davis K. L., et al. (2003). Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289, 2819–2826. 10.1001/jama.289.21.2819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. (2006). Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124, 783–801. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletaha S., Haddad L., Roozbehkia M., Bigdeli R., Asgary V., Mahmoudi M., et al. (2017). M2000 (β -D-mannuronic acid) as a novel antagonist for blocking the TLR2 and TLR4 downstream signalling pathway. Scand. J. Immunol. 85, 122–129. 10.1111/sji.12519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Erviti L., Couch Y., Richardson J., Cooper J. M., Wood M. J. A. (2011). α-synuclein release by neurons activates the inflammatory response in a microglial cell line. Neurosci. Res. 69, 337–342. 10.1016/j.neures.2010.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravalli R. N., Hu S., Lokensgard J. R. (2008). Inhibition of toll-like receptor signaling in primary murine microglia. J. NeuroImmune Pharmacol. 3, 5–11. 10.1007/s11481-007-9097-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arel-Dubeau A.-M., Longpré F., Bournival J., Tremblay C., Demers-Lamarche J., Haskova P., et al. (2015). Cucurbitacin E has neuroprotective properties and autophagic modulating activities on dopaminergic neurons. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014:15. 10.1155/2014/425496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslanidis A., Karlstetter M., Scholz R., Fauser S., Neumann H., Fried C., et al. (2015). Activated microglia/macrophage whey acidic protein (AMWAP) inhibits NFκB signaling and induces a neuroprotective phenotype in microglia. J. Neuroinflammation 12:77. 10.1186/s12974-015-0296-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanassiadou A., Voutsinas G., Psiouri L., Leroy E., Polymeropoulos M. H., Ilias A., et al. (1999). Genetic analysis of families with Parkinson disease that carry the Ala53Thr mutation in the gene encoding α-synuclein. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 65, 555–558. 10.1086/302486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M., Nakajo S., Tu P. H., Tomita T., Nakaya K., Lee V. M., et al. (1998). Aggregation of α-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am. J. Pathol. 152, 879–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock A. A., Wirenfeldt M., Holm T., Nielsen H. H., Dissing-Olesen L., Toft-Hansen H., et al. (2006). Toll-like receptor 2 signaling in response to brain injury: an innate bridge to neuroinflammation. J. Neurosci. 26, 12826–12837. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4937-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachstetter A. D., Xing B., Van Eldik L. J. (2014). The p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase limits the CNS proinflammatory cytokine response to systemic lipopolysaccharide, potentially through an IL-10 dependent mechanism. J. Neuroinflammation 11:175. 10.1186/s12974-014-0175-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D., Villén J., Shin C., Camargo F. D., Gygi S. P., Bartel D. P. (2008). The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature 455, 64–71. 10.1038/nature07242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bala S., Marcos M., Kodys K., Csak T., Catalano D., Mandrekar P., et al. (2011). Up-regulation of microRNA-155 in macrophages contributes to increased Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFα) production via increased mRNA half-life in alcoholic liver disease. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1436–1444. 10.1074/jbc.M110.145870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels A. L., Willemsen A. T. M., Doorduin J., de Vries E. F. J., Dierckx R. A., Leenders K. L. (2010). [11C]-PK11195 PET: quantification of neuroinflammation and a monitor of anti-inflammatory treatment in Parkinson's disease? Park. Relat. Disord. 16, 57–59. 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Guerrero E., Grocott H. P., Levy J. H., Stierer K. A., Hogue C. W., Cheung A. T., et al. (2007). A Phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study of eritoran (E5564), a lipid a antagonist, in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth. Analg. 104, 378–383. 10.1213/01.ane.0000253501.07183.2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béraud D., Hathaway H. A., Trecki J., Chasovskikh S., Johnson D. A., Johnson J. A., et al. (2013). Microglial activation and antioxidant responses induced by the Parkinson's disease protein α-synuclein. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 8, 94–117. 10.1007/s11481-012-9401-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer H., Birkmayer W., Hornykiewicz O., Jellinger K., Seitelberger F. (1973). Brain dopamine and the syndromes of Parkinson and Huntington: clinical, morphological and neurochemical correlations. J. Neurol. Sci. 20, 415–455. 10.1016/0022-510X(73)90175-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block M. L., Zecca L., Hong J. S. (2007). Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 57–69. 10.1038/nrn2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock S., Murgueitio M. S., Wolber G., Weindl G. (2016). Acute myeloid leukaemia-derived Langerhans-like cells enhance Th1 polarization upon TLR2 engagement. Pharmacol. Res. 105, 44–53. 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Del Tredici K. (2008). Invited Article: nervous system pathology in sporadic Parkinson disease. Neurology 70, 1916–1925. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312279.49272.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Del Tredici K. (2017). neuropathological staging of brain pathology in sporadic Parkinson's disease: separating the wheat from the chaff. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 7, S73–S87. 10.3233/JPD-179001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Del Tredici K., Rüb U., De Vos R. A. I., Jansen Steur E. N. H., Braak E. (2003). Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 197–211. 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breydo L., Wu J. W., Uversky V. N. (2012). α-Synuclein misfolding and Parkinson's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1822, 261–285. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown V., Brown R. A., Ozinsky A., Hesselberth J. R., Fields S. (2006). Binding specificity of toll-like receptor cytoplasmic domains. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 742–753. 10.1002/eji.200535158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun P., Giron M. C., Qesari M., Porzionato A., Caputi V., Zoppellaro C., et al. (2013). Toll-like receptor 2 regulates intestinal inflammation by controlling integrity of the enteric nervous system. Gastroenterology 145, 1323–1333. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buwitt-Beckmann U., Heine H., Wiesmüller K. H., Jung G., Brock R., Akira S., et al. (2006). TLR1- and TLR6-independent recognition of bacterial lipopeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9049–9057. 10.1074/jbc.M512525200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso A. L., Guedes J. R., Pereira de Almeida L., Pedroso de Lima M. C. (2012). miR-155 modulates microglia-mediated immune response by down-regulating SOCS-1 and promoting cytokine and nitric oxide production. Immunology 135, 73–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03514.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Nunez G. (2010). Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 826–837. 10.1038/nri2873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang S. M., Hernan M. A., Schwarzschild M., Willet W., Colditz G., et al. (2003). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 28, 193–196. 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Chen J., Wang H., Shi J., Wu K., Liu S., et al. (2013a). HCV-induced miR-21 contributes to evasion of host immune system by targeting MyD88 and IRAK1. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003248. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Liu W., Sun T., Huang Y., Wang Y., Deb D. K., et al. (2013b). 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D promotes negative feedback regulation of TLR signaling via targeting microRNA-155-SOCS1 in macrophages. J. Immunol. 190, 3687–3695. 10.4049/jimmunol.1203273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K., Wang X., Zhang S., Yin H. (2012). Discovery of small-molecule inhibitors of the TLR1/TLR2 complex. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 51, 12246–12249. 10.1002/anie.201204910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung Y. C., Ko H. W., Bok E., Huh S. H., Nam J. H., Jin B. K. (2010). The role of neuroinflammation on the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. BMB Rep. 43, 225–232. 10.5483/BMBRep.2010.43.4.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K., Peggie M., Plater L., Sorcek R. J., Young E. R. R., Madwed J. B., et al. (2011). Novel cross-talk within the IKK family controls innate immunity. Biochem. J. 434, 93–104. 10.1042/BJ20101701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway K. A., Harper J. D., Lansbury P. T. (1998). Accelerated in vitro fibril formation by a mutant α-synuclein linked to early-onset Parkinson disease. Nat. Med. 4, 1318–1320. 10.1038/3311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway K. A., Harper J. D., Lansbury P. T. (2000). Fibrils formed in vitro from α-synuclein and two mutant forms linked to Parkinson's disease are typical amyloid. Biochemistry 39, 2552–2563. 10.1021/bi991447r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway K. A., Rochet J. C., Bieganski R. M., Lansbury P. T. (2001). Kinetic stabilization of the α-synuclein protofibril by a dopamine-α-synuclein adduct. Science 294, 1346–1349. 10.1126/science.1063522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Z. D., Johnson K. W., Pavlicova M., Glass A., Vosburg S. K., Sullivan M. A., et al. (2016). The effects of ibudilast, a glial activation inhibitor, on opioid withdrawal symptoms in opioid-dependent volunteers. Addict. Biol. 21, 895–903. 10.1111/adb.12261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Zhu L., Xia X., Wang H. Y., Legras X., Hong J., et al. (2010). NLRC5 negatively regulates the NF-κB and type I interferon signaling pathways. Cell 141, 483–496. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniele S. G., Béraud D., Davenport C., Cheng K., Yin H., Maguire-Zeiss K. A. (2015). Activation of MyD88-dependent TLR1/2 signaling by misfolded α-synuclein, a protein linked to neurodegenerative disorders. Sci. Signal. 8:ra45. 10.1126/scisignal.2005965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzer K. M., Haasen D., Karow A. R., Moussaud S., Habeck M., Giese A., et al. (2007). Different species of α-synuclein oligomers induce calcium influx and seeding. J. Neurosci. 27, 9220–9232. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2617-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasu M. R., Riosvelasco A. C., Jialal I. (2009). Candesartan inhibits Toll-like receptor expression and activity both in vitro and in vivo. Atherosclerosis 202, 76–83. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D., Grutzendler J., Yang G., Kim J. V., Zuo Y., Jung S., et al. (2005). ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 752–758. 10.1038/nn1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lau L. M. L., Breteler M. M. B. (2006). Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet. Neurol. 5, 525–535. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70471-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleersnijder A., Gerard M., Debyser Z., Baekelandt V. (2013). The remarkable conformational plasticity of α-synuclein: blessing or curse? Trends Mol. Med. 19, 368–377. 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa A. A., Reis R., Bento-Torres J., Trévia N., de Lins N. A. A., Passos A., et al. (2011). Influence of enriched environment on viral encephalitis outcomes: behavioral and neuropathological changes in albino Swiss mice. PLoS ONE 6:e15597. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desplats P., Lee H.-J., Bae E.-J., Patrick C., Rockenstein E., Crews L., et al. (2009). Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 13010–13015. 10.1073/pnas.0903691106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer U., Newman A. J., Luth E. S., Bartels T., Selkoe D. (2013). In vivo cross-linking reveals principally oligomeric forms of α-synuclein and β-synuclein in neurons and non-neural cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6371–6385. 10.1074/jbc.M112.403311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dev K. K., Hofele K., Barbieri S., Buchman V. L., Van Der Putten H. (2003). Part II: α-synuclein and its molecular pathophysiological role in neurodegenerative disease. Neuropharmacology 45, 14–44. 10.1016/S0028-3908(03)00140-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didierlaurent A., Brissoni B., Velin D., Aebi N., Tardivel A., Käslin E., et al. (2006). Tollip regulates proinflammatory responses to interleukin-1 and lipopolysaccharide. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 735–742. 10.1128/MCB.26.3.735-742.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding T. T., Lee S., Rochet J.-C., Lansbury P. T. (2002). Annular α-synuclein protofibrils are produced when spherical protofibrils are incubated in solution or bound to brain-derived membranes †. Biochemistry 41, 10209–10217. 10.1021/bi020139h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorn K. J., Moors T., Drukarch B., van de Berg W. D. J., Lucassen P. J., van Dam A.-M. (2014). Microglial phenotypes and toll-like receptor 2 in the substantia nigra and hippocampus of incidental Lewy body disease cases and Parkinson's disease patients. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2, 1–17. 10.1186/s40478-014-0090-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downer E. J., Johnston D. G. W., Lynch M. A. (2013). Differential role of Dok1 and Dok2 in TLR2-induced inflammatory signaling in glia. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 56, 148–158. 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin-Ouellet J., St-Amour I., Saint-Pierre M., Lamontagne-Proulx J., Kriz J., Barker R. A., et al. (2015). Toll-like receptor expression in the blood and brain of patients and a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18, 1–11. 10.1093/ijnp/pyu103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzamko N., Gysbers A., Perera G., Bahar A., Shankar A., Gao J., et al. (2016). Toll-like receptor 2 is increased in neurons in Parkinson's disease brain and may contribute to α-synuclein pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 133, 1–17. 10.1007/s00401-016-1648-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouilidou E., Elenis D., Papasilekas T., Stranjalis G., Gerozissis K., Ioannou P. C., et al. (2011). Assessment of α-synuclein secretion in mouse and human brain parenchyma. PLoS ONE 6:e22225. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S. (2003). Description of Parkinson's disease as a clinical syndrome. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 991, 1–14. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07458.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattahi M. J., Jamshidi A. R., Mahmoudi M., Vojdanian M., Yekaninejad M. S., Jafarnezhad-Ansariha F., et al. (2017). Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of β-d-mannuronic acid in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled, phase I/II clinical trial. Int. Immunopharmacol. 54, 112–117. 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellner L., Irschick R., Schanda K., Reindl M., Klimaschewski L., Poewe W., et al. (2013). Toll-like receptor 4 is required for α-synuclein dependent activation of microglia and astroglia. Glia 61, 349–360. 10.1002/glia.22437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari C. C., Pott Godoy M. C., Tarelli R., Chertoff M., Depino A. M., Pitossi F. J. (2006). Progressive neurodegeneration and motor disabilities induced by chronic expression of IL-1β in the substantia nigra. Neurobiol. Dis. 24, 183–193. 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H., Hasegawa M., Dohmae N., Kawashima A., Masliah E., Goldberg M. S., et al. (2002). α-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 160–164. 10.1038/ncb748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabhann J. N., Higgs R., Brennan K., Thomas W., Damen J. E., Ben Larbi N., et al. (2010). Absence of SHIP-1 results in constitutive phosphorylation of tank-binding kinase 1 and enhanced TLR3-dependent IFN-β production. J. Immunol. 184, 2314–2320. 10.4049/jimmunol.0902589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H.-M., Kotzbauer P. T., Uryu K., Leight S., Trojanowski J. Q., Lee V. M.-Y. (2008). Neuroinflammation and oxidation/nitration of α-synuclein linked to dopaminergic neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 28, 7687–7698. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard A., Pavese N., Hotton G., Turkheimer F., Es M., Hammers A., et al. (2006a). In vivo imaging of microglial activation with [11C](R)-PK11195 PET in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 21, 404–412. 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard A., Trender-Gerhard I., Turkheimer F., Quinn N. P., Bhatia K. P., Brooks D. J. (2006b). In vivo imaging of microglial activation with [11C](R)-PK11195 PET in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov. Disord. 21, 89–93. 10.1002/mds.20668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhard A., Watts J., Trender-Gerhard I., Turkheimer F., Banati R. B., Bhatia K., et al. (2004). In vivo imaging of microglial activation with [11C](R -PK11195 PET in corticobasal degeneration. Mov. Disord. 19, 1221–1226. 10.1002/mds.20162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giridharan V. V., Thandavarayan R. A., Bhilwade H. N., Ko K. M., Watanabe K., Konishi T. (2012). Schisandrin B, attenuates cisplatin-induced oxidative stress, genotoxicity and neurotoxicity through modulating NF-κB pathway in mice. Free Radic. Res. 46, 50–60. 10.3109/10715762.2011.638291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabert K., Michoel T., Karavolos M. H., Clohisey S., Baillie J. K., Stevens M. P., et al. (2016). Microglial brain region-dependent diversity and selective regional sensitivities to aging. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 504–516. 10.1038/nn.4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Chen Y., Hu X., Qian G., Ge S., Zhang J. (2013). The regulation of Toll-like receptor 2 by miR-143 suppresses the invasion and migration of a subset of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Mol. Cancer 12:77. 10.1186/1476-4598-12-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustot A., Gallea J. I., Sarroukh R., Celej M. S., Ruysschaert J.-M., Raussens V. (2015). Amyloid fibrils are the molecular trigger of inflammation in Parkinson's disease. Biochem. J. 471, 323–333. 10.1042/BJ20150617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven-Maiorov E., Keskin O., Gursoy A., Nussinov R. (2015). A structural view of negative regulation of the toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory pathway. Biophys. J. 109, 1214–1220. 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.06.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajivalili M., Pourgholi F., Majidi J., Aghebati-Maleki L., Movassaghpour A. A., Samadi Kafil H., et al. (2016). G2013 modulates TLR4 signaling pathway in IRAK-1 and TARF-6 dependent and miR-146a independent manner. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 62, 1–5. 10.14715/cmb/2016.62.4.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch U.-K. (2013). Functional diversity of microglia - how heterogeneous are they to begin with? Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7:65. 10.3389/fncel.2013.00065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M., Hsu L. J., Xia Y., Takeda A., Sisk A., Sundsmo M., et al. (1999). Oxidative stress induces amyloid-like aggregate formation of NACP/α-synuclein in vitro. Neuroreport 10, 717–721. 10.1097/00001756-199903170-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Wang Q., Yuan C., Wang Y. (2017). Downregulation of miR-7116-5p in microglia by MPP+ sensitizes TNF-α production to induce dopaminergic neuron damage. Glia 65, 1251–1263. 10.1002/glia.23153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T., Barton G. M., Flavell R. A., Medzhitov R. (2002). The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signalling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature 420, 329–333. 10.1038/nature01180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S., Abdollahi M., Azizi G., Fattahi M. J., Rastkari N., Zavareh F. T., et al. (2017). Anti-aging effects of M2000 (β-D-mannuronic acid) as a novel immunosuppressive drug on the enzymatic and non-enzymatic oxidative stress parameters in an experimental model. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 28, 249–255. 10.1515/jbcpp-2016-0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B., Baek S. (2017). Trim13 potentiates toll-like receptor 2-mediated nuclear factor κB activation via K29-linked polyubiquitination of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6. Mol. Pharmacol. 91, 307–316. 10.1124/mol.116.106716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui B., Zhang L., Zhou Q., Hui L. (2018). Pristimerin inhibits LPS-triggered neurotoxicity in BV-2 microglia cells through modulating IRAK1/TRAF6/TAK1-mediated NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways in vitro. Neurotox. Res. 33, 268–283. 10.1007/s12640-017-9837-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert-Claude M., Duc D., Dwir D., Thieren L., Sandström von Tobel J., Begka C., et al. (2016). Tollip, an early regulator of the acute inflammatory response in the substantia nigra. J. Neuroinflammation 13:303. 10.1186/s12974-016-0766-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ii M., Matsunaga N., Hazeki K., Nakamura K., Takashima K., Seya T., et al. (2006). A novel cyclohexene derivative, ethyl (6R)-6-[N-(2-Chloro-4-fluorophenyl)sulfamoyl]cyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxylate (TAK-242), selectively inhibits toll-like receptor 4-mediated cytokine production through suppression of intracellular signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 69, 1288–1295. 10.1124/mol.105.019695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innamorato N. G., Lastres-Becker I., Cuadrado A. (2009). Role of microglial redox balance in modulation of neuroinflammation. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 22, 308–314. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832a3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innamorato N. G., Rojo A. I., García-Yagüe A. J., Yamamoto M., de Ceballos M. L., Cuadrado A. (2008). The transcription factor Nrf2 is a therapeutic target against brain inflammation. J. Immunol. 181, 680–689. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi S. S. M., Jamshidi M. M., Farazmand A., Aghazadeh Z., Yousefi M., Mirshafiey A. (2017). Pharmacological effects of β-D-mannuronic acid (M2000) on miR-146a, IRAK1, TRAF6 and NF-κB gene expression, as target molecules in inflammatory reactions. Pharmacol. Rep. 69, 479–484. 10.1016/j.pharep.2017.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana M., Palencia C. A., Pahan K. (2008). Fibrillar amyloid-β peptides activate microglia via TLR2: implications for Alzheimer's disease. J. Immunol. 181, 7254–7262. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang A., Lee H. J., Suk J. E., Jung J. W., Kim K. P., Lee S. J. (2010). Non-classical exocytosis of α-synuclein is sensitive to folding states and promoted under stress conditions. J. Neurochem. 113, 1263–1274. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao S., Zhang Z., Li C., Huang M., Shi Z., Wang Y., et al. (2015). The kinase MST4 limits inflammatory responses through direct phosphorylation of the adaptor TRAF6. Nat. Immunol. 16, 246–257. 10.1038/ni.3097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M. S., Kim S. E., Heo J. Y., Lee M. E., Kim H. M., Paik S. G., et al. (2007). Crystal structure of the TLR1-TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri-acylated lipopeptide. Cell 130, 1071–1082. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. L., Lapadat R. (2002). Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 298, 1911–1912. 10.1126/science.1072682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurkin J., Schichl Y. M., Koeffel R., Bauer T., Richter S., Konradi S., et al. (2010). miR-146a is differentially expressed by myeloid dendritic cell subsets and desensitizes cells to TLR2-dependent activation. J. Immunol. 184, 4955–4965. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]