Abstract

Obesity is socially stigmatized in the U.S., especially for women. Significant research has focused on the role that the social and built environments of neighborhoods play in shaping obesity. However, the role of obesity in shaping neighborhood social structure has been largely overlooked. We test the hypothesis that large body size inhibits an individual's engagement in his or her neighborhood. Our study objectives are to assess if (1) body size (body mass index) interacts with gender to predict engagement in one's neighborhood (neighborhood engagement) and (2) if bonding social capital interacts with gender to predict neighborhood engagement independent of body size. We used data collected from the cross-sectional 2011 Phoenix Area Social Survey (PASS), which systematically sampled residents across four neighborhood types (core urban, urban fringe, suburban, retirement) across the Phoenix Metopolitian Area. Survey data was analyzed using logistic regression for 804 participants, including 35% for whom missing data was computed using multiple imputation. We found that as body size increases, women—but not men—have reduced engagement in their neighborhood, independent of bonding social capital and other key covariates (objective 1). We did not observe the interaction between gender and bonding social capital associated with neighborhood engagement (objective 2). Prior scholarship suggests obesity clusters in neighborhoods due to processes of social, economic, and environmental disadvantage. This finding suggests bi-directionality: obesity could, in turn, undermine neighborhood engagement through the mechanism of weight stigma and discrimination.

Keywords: Obesity, Neighborhoods, Gender, Weight stigma, Discrimination, Social capital, Social engagement

1. Introduction

Large body sizes are unevenly distributed across cities. A range of sociocultural factors, including low neighborhood and individual socioeconomic status (Dubowitz et al., 2012; Ludwig et al., 2011; Matheson et al., 2008; Zhang and Wang, 2004) and perceived disamenities such as low walkability, safety, and lack of usable green space or fresh food sources (Cutts et al., 2009; Lovasi et al., 2009) predict greater prevalence of neighborhood obesity and overweight. In essence, a range of social and structural dynamics place people at risk of attaining unhealthy body sizes. The uneven distribution of obesity across neighborhoods is now widely recognized to result from broader processes of social, environmental, and economic injustice (Cummins, 2014; Kinge et al., 2016).

A separate set of literature has established that large body size also tends to significantly erode social capital, or the benefits from social networks that promote cooperation for mutual interest, within communities (Anderson-Fye and Brewis, 2017). People with large body sizes are highly socially stigmatized in the U.S. and elsewhere (Brewis et al., 2011; Puhl and Heuer, 2009). Moreover, feelings of stigma lead those with large body sizes to disconnect socially as a means of coping (Brewis, Trainer, et al., 2016b). For example, they may be less likely to want to join local sports teams or exercise in public spaces (Vartanian and Novak, 2011).

Placed together, these sets of theory suggest a little-tested proposition: people's weight might also shape the forms and strength of their social and civic engagement within their neighborhoods. Using data from the 2011 Phoenix Area Social Survey (PASS), we test the proposition that large body size could inhibit engagement within one's neighborhood (neighborhood engagement).

Given the cross-sectional nature of the PASS data, we cannot imply causality in what is likely a complex bidirectional set of associations. But to strengthen our capacity to theory-build from these pilot data, we use the lens of gender. In Phoenix and across U.S. society, women are more aware of and reactive to size and weight status in their social contexts, and they tend to feel more stigmatized by it (Brewis et al., 2011; Fikkan and Rothblum, 2011).1 If the social meaning of high weight status is influencing key neighborhood social dynamics like civic engagement, then the effects should be more obvious among women than men.

Our first study objective was to test if body size, estimated as body mass index (BMI), interacts with gender to predict neighborhood civic engagement. Civic engagement includes non-political participation such as working informally to solve a community problem, volunteering, and active membership in organizations (Jenkins, 2005). Civic engagement is influenced by an array of factors that we controlled for in our model including higher neighborhood socioeconomic status (Wilkenfeld and Torney-Purta, 2012), rural neighborhood type (Greiner et al., 2004; Turcotte, 2005), majority ethnicity, older age, higher education, higher household income, and home ownership (Foster-Bey, 2008; Kim et al., 2006; Marczak et al., 2009) as well as by gender (Son and Lin, 2008).

Our second objective was to test if individual measures of social capital interact with gender to predict neighborhood engagement independent of body size. Social capital arises from the trust, information exchange, reciprocity, collective action, and collective identities associated with social networks (Putnam, 2001). We focused on bonding forms of social capital in this study because we have previously identified this as significantly correlated with relative neighborhood (dis)advantage (Wutich et al., 2014) and neighborhood engagement (Larsen, 2004) across the Phoenix metropolitan area. Furthermore, low social capital has been previously shown to predict lower civic engagement (Collins et al., 2014) and likelihood of obesity (Muckenhuber et al., 2015) and to co-vary with gender so that women are less effectively networked, with potential externalities on career, life in the public sphere, and reinforced gender roles in personal life (Gidengil et al., 2006).

2. Methods

2.1. Data

Data were drawn from the 2011 PASS, a cross-sectional survey that assesses the neighborhood and environmental perceptions, values, and behaviors of people living in the Phoenix Metropolitan Area. Methods have been described in detail elsewhere (CAP LTER, 2016); in brief, the PASS neighborhood sampling was based on a network of ecosystems monitoring sites in the Phoenix metropolitan area and identification of communities based on demographic criteria. Ninety-four residential sites were cross-classified according to location based on physical distance from both downtown and undeveloped land (core - within 5 miles of downtown Phoenix or 1.5 miles from other large city centers; fringe - moderate amount of undeveloped land within a mile; suburban; retirement - median age > 55 years) and median household income (low <$35,000; middle, $35,000–70,000; high >$70,000). Eight neighborhood classifications resulted, with five neighborhoods per group plus an additional five were selected for a total 45 neighborhoods to represent variation in race and ethnicity (“white” neighborhoods ≥ 66% non-Hispanic white; “Hispanic” ≥ 50% Hispanic; “mixed” all others), homeownership, and municipalities.

Data were collected from surveys conducted on-line, over the phone, or in-person from May 2011 to January 2012. Forty heads of household ≥18 years were invited to participate from each of the 45 neighborhoods; 757 of these were selected due to participation in the 2006 PASS and the rest were randomly selected from Maricopa County Tax Assessor's records. Through multiple contacts and graduated incentives (from randomly assigned $10/20/30 to $30 to $50), 806 individuals completed the survey in either Spanish or English for a response rate of 44% (CAP LTER, 2016). Of those participating, 35% (n = 281) had data missing.

To address the missing data, we used multiple imputation to generate copies of the data set, each with different estimates of the missing values. To meet the assumption that data were missing at random and improve the quality of the imputed values, we included an auxiliary variable not used in our models but associated with important model variables (White et al., 2010). The auxiliary variable chosen (belief that participant/similar individuals can make the neighborhood better (range 1–4), was associated with missingness of values for bonding social capital. The number of imputations was 40 based on the highest estimated RVI (36%) and FMI (27%) which was associated with household income. Imputation was conducted on the 23 variables in the regression analyses plus auxiliary variable and estimates were combined. The final sample size was 804 respondents, after excluding two respondents with physically impossible BMI values.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome: neighborhood engagement

Neighborhood engagement was a binary variable: “In the past 12 months, have you gotten together informally with or worked with others in your community or neighborhood to try to deal with some community issue or problem?”

2.2.2. Key predictors and covariate: gender, body size, and bonding social capital

Gender was binary male/female. Continuous BMI was the body size variable, derived from self-reported weight and height.

We adapted Larsen's (2004) definition of bonding social capital to create a summary measure comprised of trust between neighbors and association. Trust encompassed sense of the neighborhood's connectedness, if respondent trusted neighbors, and whether they thought neighbors would come together to solve a serious problem (response range 1–4). Association included frequency of visits with neighbors (0–4), frequency of doing favors such as watching children or helping with shopping (0–4), or feeling of knowing neighbors (0–3). Our summative variable of bonding social capital had a range of 3–23, with higher values meaning greater social capital.

2.2.3. Covariates

Covariates included age (years), race (White/non-White), ethnicity (Hispanic/non-Hispanic), general health status (1 = poor, 4 = excellent), and household size. Household income (≤$40,000, $40,001–$80,000, ≥$80,001), education (non-college/college educated or above), home ownership, and employment status were used as indicators of respondent socioeconomic status. Residential history was assessed with nativity (born in Arizona/not) and number of years at current address.

2.2.4. Neighborhood characteristics

We classified respondents into the four types defined above: urban core, urban fringe, suburban, and retirement. Neighborhood characteristics were further classified by respondent's marital status, education, ethnicity, and household income, and by percentage of the neighborhood households below the poverty line, with married couples, with a graduate/professional degree, and of Hispanic/Latino origin2 (Supplementary Table 1).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The first logistic regression models tested the effects of body size (BMI) and bonding social capital on neighborhood engagement after controlling for neighborhood type (model 1), individual characteristics (model 2), and neighborhood characteristics (model 3). Subsequent models tested the moderating effects of gender on the association between body size (BMI) and neighborhood engagement (model 4), bonding social capital and neighborhood engagement (model 5), and both (model 6). Using a hypothetical typical individual based on respondent demographics, we predicted the probability of individuals' neighborhood engagement at different levels of BMI. To account for nesting of individuals within neighborhood, we estimated clustered robust standard errors followed by sensitivity analysis and found no substantial difference (not reported).

3. Results

There was a significant positive association between bonding social capital and neighborhood engagement, but not between BMI and neighborhood engagement (Table 1, model 1). These results were consistent after controlling for individual (model 2) and neighborhood characteristics (model 3). Respondents living in the urban fringe and suburban neighborhoods had higher levels of neighborhood engagement, as did respondents in neighborhoods with higher proportions of graduate/professional degrees and of Hispanic/Latino origin.

Table 1.

Estimated effects of body size (body mass index) and bonding social capital on neighborhood engagement and interactions of gender with body size and bonding social capital on engagement in one’s neighborhood in Phoenix, AZ (n=804)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds | S.E. | 95% C.I. | Odds | Odds | S.E. | 95% C.I. | Odds | S.E. | Odds | S.E. | 95% C.I. | Odds | S.E. | 95% C.I. | Odds | S.E. | 95% C.I. | ||

| Individual characteristics | Interactions between Gender | ||||||||||||||||||

| Body mass index | 0.98 | 0.02 | [0.95; 1.02] | 1.00 | 0.02 | [0.95; 1.04] | 1.00 | 0.02 | [0.95; 1.04] | and Body mass index | 1.10 | 0.04 | [1.02; 1.18] | 1.10 | 0.04 | [1.02; 1.18] | |||

| Bonding social capital | 1.18 | 0.03 | [1.12; 1.24] | 1.20 | 0.03 | [1.15; 1.25] | 1.20 | 0.03 | [1.15; 1.26] | and Bonding social capital | 0.95 | 0.05 | [0.86; 1.05] | 0.96 | 0.05 | [0.86; 1.06] | |||

| Male | 1.15 | 0.23 | [0.78; 1.70] | 1.16 | 0.23 | [0.78; 1.71] | Individual characteristics | ||||||||||||

| White | 1.03 | 0.32 | [0.56; 1.91] | 1.05 | 0.32 | [0.57; 1.92] | Body mass index | 0.96 | 0.03 | [0.91; 1.01] | 1.00 | 0.02 | [0.95; 1.04] | 0.96 | 0.03 | [0.90; 1.01] | |||

| Hispanic | 0.82 | 0.35 | [0.35; 1.90] | 0.76 | 0.34 | [0.32; 1.83] | Bonding social capital | 1.20 | 0.03 | [1.15; 1.26] | 1.23 | 0.04 | [1.16; 1.31] | 1.23 | 0.04 | [1.16; 1.31] | |||

| Age (years) | 1.01 | 0.01 | [0.99; 1.03] | 1.01 | 0.01 | [0.99; 1.03] | Male | 0.10 | 0.09 | [0.01; 0.66] | 2.45 | 1.97 | [0.51; 11.80] | 0.19 | 0.23 | [0.02; 2.03] | |||

| Years in the current address | 0.98 | 0.01 | [0.96; 1.00] | 0.98 | 0.01 | [0.96; 1.00] | White | 1.08 | 0.33 | [0.59; 1.97] | 1.06 | 0.32 | [0.59; 1.93] | 1.09 | 0.33 | [0.60; 1.98] | |||

| Born in Arizona | 1.21 | 0.29 | [0.75; 1.95] | 1.23 | 0.32 | [0.74; 2.03] | Hispanic | 0.80 | 0.35 | [0.34; 1.89] | 0.79 | 0.35 | [0.33; 1.87] | 0.82 | 0.36 | [0.35; 1.92] | |||

| General health | 1.19 | 0.15 | [0.92; 1.54] | 1.19 | 0.15 | [0.93; 1.52] | Age (years) | 1.01 | 0.01 | [0.99; 1.03] | 1.01 | 0.01 | [0.99; 1.03] | 1.01 | 0.01 | [0.99; 1.03] | |||

| College or above education | 1.83 | 0.45 | [1.12; 2.98] | 1.85 | 0.48 | [1.12; 3.07] | Years in the current address | 0.98 | 0.01 | [0.95; 1.00] | 0.98 | 0.01 | [0.96; 1.00] | 0.98 | 0.01 | [0.95; 1.00] | |||

| Own home | 1.68 | 0.53 | [0.91; 3.12] | 1.81 | 0.62 | [0.93; 3.53] | Born in Arizona | 1.28 | 0.34 | [0.77; 2.14] | 1.25 | 0.32 | [0.76; 2.07] | 1.30 | 0.34 | [0.78; 2.17] | |||

| Employed | 1.67 | 0.38 | [1.07; 2.60] | 1.60 | 0.38 | [1.01; 2.54] | General health | 1.20 | 0.16 | [0.93; 1.55] | 1.18 | 0.15 | [0.92; 1.52] | 1.20 | 0.16 | [0.93; 1.54] | |||

| Household size | 0.94 | 0.06 | [0.82; 1.07] | 0.95 | 0.07 | [0.83; 1.09] | College or above education | 1.89 | 0.49 | [1.13; 3.14] | 1.87 | 0.48 | [1.13; 3.10] | 1.90 | 0.49 | [1.14; 3.17] | |||

| Annual household incomea | Own home | 1.76 | 0.62 | [0.88; 3.49] | 1.83 | 0.62 | [0.94; 3.55] | 1.77 | 0.62 | [0.89; 3.51] | |||||||||

| Medium income ($40,001-80,000) | 0.79 | 0.21 | [0.47; 1.34] | 0.84 | 0.25 | [0.47; 1.51] | Employed | 1.65 | 0.38 | [1.05; 2.61] | 1.61 | 0.38 | [1.01; 2.56] | 1.66 | 0.39 | [1.05; 2.62] | |||

| High income (>$80,001) | 0.64 | 0.18 | [0.37; 1.10] | 0.63 | 0.21 | [0.33; 1.20] | Household size | 0.95 | 0.07 | [0.83; 1.09] | 0.95 | 0.07 | [0.83; 1.09] | 0.95 | 0.07 | [0.83; 1.09] | |||

| Neighborhood characteristics | Household incomea | ||||||||||||||||||

| Below the poverty line | 0.47 | 0.47 | [0.07; 3.38] | Medium income ($40,001-80,000) | 0.84 | 0.25 | [0.47; 1.52] | 0.84 | 0.25 | [0.46; 1.51] | 0.84 | 0.25 | [0.47; 1.51] | ||||||

| Married households | 0.28 | 0.18 | [0.08; 1.01] | High income (>$80,001) | 0.64 | 0.21 | [0.33; 1.23] | 0.63 | 0.21 | [0.33; 1.21] | 0.64 | 0.21 | [0.33; 1.23] | ||||||

| Graduate or professional degree | 14.58 | 15.28 | [1.87; 113.82] | Neighborhood characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Hispanic or Latino origin | 4.23 | 2.03 | [1.65; 10.86] | Below the poverty line | 0.33 | 0.33 | [0.05; 2.34] | 0.42 | 0.43 | [0.06; 3.16] | 0.33 | 0.33 | [0.05; 2.30] | ||||||

| Neighborhood typesb | Married households | 0.26 | 0.17 | [0.07; 0.94] | 0.26 | 0.18 | [0.07; 1.00] | 0.26 | 0.17 | [0.07; 0.92] | |||||||||

| Fringe | 1.32 | 0.46 | [0.67; 2.60] | 1.95 | 0.63 | [1.04; 3.68] | Graduate or professional degree | 19.80 | 21.14 | [2.44; 160.56] | 19.68 | 20.84 | [2.47; 156.77] | 19.33 | 20.37 | [2.45; 152.43] | |||

| Suburban | 1.63 | 0.46 | [0.94; 2.82] | 2.22 | 0.61 | [1.29; 3.82] | Hispanic or Latino origin | 4.48 | 2.24 | [1.68; 11.91] | 3.67 | 1.94 | [1.30; 10.34] | 4.33 | 2.21 | [1.59; 11.78] | |||

| Retired | 1.34 | 0.49 | [0.66; 2.74] | 2.20 | 0.90 | [0.98; 4.93] | Neighborhood typesb | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.07 | 0.04 | [0.03; 0.20] | 0.00 | 0.00 | [0.00; 0.03] | 0.00 | 0.00 | [0.00; 0.03] | Fringe | 1.91 | 0.61 | [1.02; 3.56] | 1.96 | 0.63 | [1.04; 3.67] | 1.91 | 0.60 | [1.03; 3.55] |

| F static | 32.81 | 7.91 | 7.16 | Suburban | 2.17 | 0.59 | [1.28; 3.70] | 2.22 | 0.61 | [1.30; 3.80] | 2.17 | 0.58 | [1.28; 3.68] | ||||||

| Retired | 2.11 | 0.85 | [0.96; 4.67] | 2.15 | 0.89 | [0.96; 4.86] | 2.08 | 0.85 | [0.93; 4.61] | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.01 | 0.01 | [0.00; 0.09] | 0.00 | 0.00 | [0.00; 0.02] | 0.01 | 0.01 | [0.00; 0.07] | ||||||||||

| Wald χ2 | 7.65 | 7.38 | 7.83 | ||||||||||||||||

Note: Logistic regression analysis results with the dataset after imputing missing data in Stata 14.2; bold if significant at the p-value 0.05 level; a reference group is low income (<$40,000); b Reference group is urban core neighborhood; C.I. stands for confidence interval.

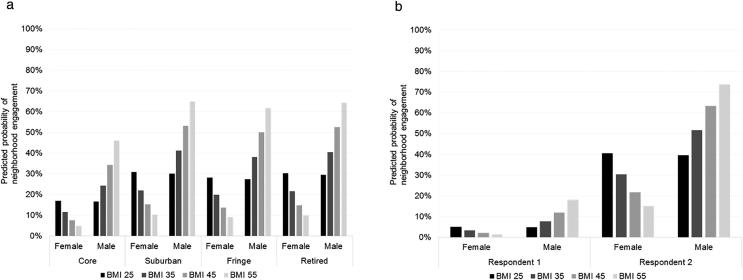

Gender interacted with BMI (Table 1, model 4) but not bonding social capital (model 5), so that higher BMI predicted higher neighborhood engagement for men but lower engagement for women. For example, when BMI is at 25 (upper range for a medically “healthy” BMI), the predicted probabilities of neighborhood engagement for both males and females with the same demographic characteristics in the suburban neighborhood are similar (33% and 32%, respectively). However, when BMI was increased to 37 (medically categorized as “morbidly obese”), the probability that a male would engage in the neighborhood was substantially higher than that of a female (42% and 18%, respectively). This gender gap widened as body size (BMI) increased. These results remained consistent when both interactions were included in the same model (model 6).

The higher engagement of men compared to women at higher body sizes persisted across neighborhood types (Fig. 1a). Neighborhood engagement was higher and similar among individuals in suburban and fringe compared with the core and retired neighborhoods. The gendered pattern remained even with variation in key individual characteristics associated with civic engagement, including ethnicity, education, age, and home ownership (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a. Predicted probability of neighborhood engagement by gender and body size (body mass index) residing in four types of neighborhoods in Phoenix, Arizona in 2011.

Note: predicted probability was calculated for a hypothetical respondent who was Hispanic non-White, college educated or above, employed, medium income, a homeowner, and not born in Arizona based on demographic characteristics (Supplemental Table 1); the rest of the covariates are set to their mean values within each gender (Table 1, model 4).

Note: predicted probability was calculated for a hypothetical respondent who was Hispanic non-White, college educated or above, employed, medium income, a homeowner, and not born in Arizona based on demographic characteristics (Supplemental Table 1); the rest of the covariates are set to their mean values within each gender (Table 1, model 4).

b. Predicted probability for two hypothetical individuals living in Phoenix, Arizona with characteristics known to covary with high and low neighborhood engagement.

Note: Respondent 1 is 1 is 35 years old, non-White Hispanic, high school educated, not a homeowner, employed, medium income, not born in Arizona, and lives in the core neighborhood. Respondent 2 is 60 years old, non-Hispanic White, college educated or above, a homeowner, employed, medium income, not born in Arizona, and lives in a suburban neighborhood.

4. Discussion and conclusion

While cross-sectional, our findings provide a novel observation: that larger body sizes limit women's—but not men's—neighborhood engagement. This effect was independent of the level of bonding social capital and persisted across neighborhood types and individual characteristics. It suggests the possibility that the gendered, personal social meanings of large body size, such as those connected to discrimination and stigma, may be shaping broader neighborhood socio-political dynamics.

Further research is needed to clarify if the pattern appears consistently and to explicate the implied mechanism. It may be that larger women are excluded from neighborhood social engagement and local political opportunities by the discrimination of others (Miller and Lundgren, 2010), that felt stigma discourages larger-bodied women (but not men) from engaging socially (Brewis et al., 2011), or both.

The observation that high weight can reduce neighborhood engagement provides further evidence that cities are places where multiple vulnerabilities meet. Weight should be added to theoretical models considering how varied forms of disadvantage, such as gender, low income, minority status, and spatial disadvantage, intersect with place to undermine the health and well-being of individuals and their communities. In this case, large body size is suggested as a possible driver of social vulnerability that intersects with gender within neighborhoods.

Strengths of the study include the systematic neighborhood sampling strategy of PASS and robust analysis of the association of BMI and gender interactions on neighborhood engagement while controlling for key individual- and neighborhood-level characteristics. Limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the data that preluded evaluation of causality, the low response rate that may reflect selection bias and perhaps lower sense of engagement, and response bias associated with self-reported height and weight measures. Finally, the binary measure of engagement in one's neighborhood precluded assessment of variability in frequency of outcomes and failed to capture the many rich dimensions of engagement in one's neighborhood.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Individual and neighborhood characteristics by neighborhood types for participants in the 2011 Phoenix Area Social Survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Analyses were supported by the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust through an award to Mayo Clinic/ASU Obesity Solutions. The Phoenix Area Social Survey was conducted with funding from the National Science Foundation under grant number DEB-1026865, Central Arizona-Phoenix Long-Term Ecological Research Program (CAP LTER).

Footnotes

Our team has been conducting ethnographic research on weight and neighborhood stigma for over a decade (see Brewis et al., 2011, Brewis et al., 2016a, Brewis et al., 2016b; Brewis and Wutich, 2015; Raves et al., 2016). Brewis et al., 2011; Hruschka et al., 2011 confirm the close connections between social networks and weight in a sample of Phoenix women.

Based on 2010 U.S. Census and American Community Survey 5-year estimates (2006–2010).

Based on 2010 U.S. Census and American Community Survey 5-year estimates (2006–2010).

Contributor Information

Roseanne C. Schuster, Email: roseanne.schuster@asu.edu.

Seung Yong Han, Email: shan32@asu.edu.

Alexandra A. Brewis, Email: alex.brewis@asu.edu.

Amber Wutich, Email: amber.wutich@asu.edu.

References

- Anderson-Fye E., Brewis A.A., editors. Fat Planet: Obesity, Culture, and Symbolic Body Capital. SAR Press and University of New Mexico Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brewis A., Brennhofer S., van Woerden I., Bruening M. Weight stigma and eating behaviors on a college campus: are students immune to stigma's effects? Prev. Med. Rep. 2016;4:578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis A.A., Hruschka D.J., Wutich A. Vulnerability to fat-stigma in women's everyday relationships. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis A., Trainer S., Han S., Wutich A. Publically misfitting: extreme weight and the everyday production and reinforcement of felt stigma. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2016:1–20. doi: 10.1111/maq.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewis A.A., Wutich A. A world of suffering? Biocultural approaches to fat stigma in the global contexts of the obesity epidemic. Ann. Anthropol. Pract. 2015;38:269–283. [Google Scholar]

- CAP LTER . Central Arizona-Phoenix Long-Term Ecological Research; 2016. Phoenix Area Social Survey 2011 Codebook. [Google Scholar]

- Collins C.R., Neal J.W., Neal Z.P. Transforming individual civic engagement into community collective efficacy: the role of bonding social capital. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014;54:328–336. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S. Food deserts. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Health, Illness, Behavior, and Society. 2014:562–564. [Google Scholar]

- Cutts B.B., Darby K.J., Boone C.G., Brewis A. City structure, obesity, and environmental justice: an integrated analysis of physical and social barriers to walkable streets and park access. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009;69:1314–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz T., Ghosh Dastidar M., Eibner C. The women's health initiative: the food environment, neighborhood socioeconomic status, BMI, and blood pressure. Obesity. 2012;20:862–871. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fikkan J.L., Rothblum E.D. Is fat a feminist issue? Exploring the gendered nature of weight bias. Sex Roles. 2011;66:575–592. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Bey J. The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement; 2008. Do Race, Ethnicity, Citizenship and Socio-Economic Status Determine Civic Engagement? [Google Scholar]

- Gidengil R., O'Neill P., Norris P., Inglehart R. Gendering social capital. In: Gidengil R., O'Neill P., editors. Gender and Social Capital, Bowling in Women's Leagues? Routledge; 2006. pp. 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner K.A., Li C., Kawachi I., Hunt D.C., Ahluwalia J.S. The relationships of social participation and community ratings to health and health behaviors in areas with high and low population density. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004;59:2303–2312. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruschka D.J., Brewis A.A., Wutich A., Morin B. Shared norms and their explanation for the social clustering of obesity. Am. J. Phys. 2011 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins K. Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement; 2005. Gender and Civic Engagement: Secondary Analysis of Survey Data. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.C., Kim Y.-C., Jung J.Y., Jung J.-Y., Ball-Rokeach S.J., Ball-Rokeach S.J. “Geo-ethnicity” and neighborhood engagement: a communication infrastructure perspective. Polit. Commun. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Kinge J.M., Steingrímsdóttir Ó.A., Strand B.H., Kravdal Ø. Can socioeconomic factors explain geographic variation in overweight in Norway? SSM - Pop Health. 2016;2:333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen L. Bonding and bridging: understanding the relationship between social capital and civic action. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2004;24:64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lovasi G.S., Hutson M.A., Guerra M., Neckerman K.M. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol. Rev. 2009;31:7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J., Sanbonmatsu L., Gennetian L. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes — a randomized social experiment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:1509–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczak R., Cornwell B., Laumann E.O., Schumm L.P. The social connectedness of older adults: a national profile. Am. Soc. Rev. 2009;73:1–19. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson F.I., Moineddin R., Glazier R.H. The weight of place: a multilevel analysis of gender, neighborhood material deprivation, and body mass index among Canadian adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008;66:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B.J., Lundgren J.D. An experimental study of the role of weight bias in candidate evaluation. Obesity. 2010;18:712–718. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muckenhuber J.M., Dorner T.E., Burkert N., Groschadl F., Freidl W. Low social capital as a predictor for the risk of obesity. Health Soc. Work. 2015;40:e51–e58. [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R.M., Heuer C.A. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity. 2009;17:941–964. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Simon and Schuster; 2001. Bowling Alone. [Google Scholar]

- Raves D.M., Brewis A., Trainer S., Han S.-Y., Wutich A. Bariatric surgery patients' perceptions of weight-related stigma in healthcare settings impair post-surgery dietary adherence. Front. Psychol. 2016;7:45-14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son J., Lin N. Social capital and civic action: a network-based approach. Soc. Sci. Res. 2008;37:330–349. [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte M., Bourjos Social engagement and civic participation: are rural and small town populations really at an advantage? Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin. 2005;6:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian L.R., Novak S.A. Internalized societal attitudes moderate the impact of weight stigma on avoidance of exercise. Obesity. 2011;19:757–762. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White I.R., Royston P., Wood A.M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat. Med. 2010;30:377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkenfeld B., Torney-Purta J. A cross-context analysis of civic engagement linking CIVED and U.S. census data. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2012;11 [Google Scholar]

- Wutich A., Ruth A., Brewis A., Boone C. Stigmatized neighborhoods, social bonding, and health. Med. Anthropol. Q. 2014;28:556–577. doi: 10.1111/maq.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Wang Y. Trends in the association between obesity and socioeconomic status in U.S. adults: 1971 to 2000. Obes. Res. 2004;12:1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Individual and neighborhood characteristics by neighborhood types for participants in the 2011 Phoenix Area Social Survey.