Abstract

The porcine intestinal mucosa require large amounts of energy for nutrient processing and cellular functions and is vulnerable to injury by weaning stress involving bioenergetics failure. The mitochondrial bioenergetic measurement in porcine enterocytes have not been defined. The present study was to establish a method to measure mitochondrial respiratory function and profile mitochondrial function of IPEC-J2 using cell mito stress test and glycolysis stress test assay by XF24 extracellular flux analyzer. The optimal seeding density and concentrations of the injection compounds were determined to be 40,000 cells/well as well as 0.5 µM oligomycin, 1 µM carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and 1 µM rotenone & antimycin A, respectively. The profiles of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis confirmed that porcine enterocyte preferentially derived much more energy from glutamine than glucose. These results will provide a basis for further study of mitochondrial function and bioenergetics of the porcine small intestine.

Keywords: Mitochondrial respiration, Glycolysis, Extracellular flux analysis, Porcine enterocyte

1. Introduction

The porcine intestinal mucosa requires large amounts of energy for nutrient processing and other basic cellular functions and accounts for 25% of total body oxygen consumption (Vaugelade et al., 1994). At the same time, the intestinal mucosa is vulnerable to injury in morphology and function after weaning, which may involve bioenergetics failure induced by mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequently short energy supply (Lacza et al., 2001, Tan et al., 2010, Tan et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2013, Xiao et al., 2013, Wang et al., 2015). Xiong et al. (2015) demonstrated that early-weaning lead to the down-regulations of proteins involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, beta-oxidation and the glycolysis pathway in the upper and middle villus of piglets but up-regulations of glycolysis-related proteins. Intestinal epithelia cell restitution including crypt cell proliferation, differentiation and migration after injury appear to depend strongly on energy availability during the first 2 days post-weaning (Lallès et al., 2004, Van Beers-Schreurs et al., 1998).

Mitochondria are considered as the major suppliers of ATP to maintain biological function. Substrates such as oxygen, glucose, glutamine, and so on were uptaken and subsequently conversed into energy through a series of enzymatically controlled oxidation and reduction reactions, resulting in the production of ATP (Nicholls et al., 2010). Some methods have applied to measure mitochondrial function and dysfunction and the extracellular flux analysis is the best assay for intact cells (Brand and Nicholls, 2011, Salabei et al., 2014), but the mitochondrial bioenergetic measurement in porcine enterocytes have not been defined. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to establish a method to measure mitochondrial respiratory function and profile mitochondrial function of IPEC-J2 under normal conditions using extracellular flux analysis, which will provide a basis for further study of mitochondrial function and bioenergetics of the porcine small intestine.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

XF cell mito stress test kit including oligomycin, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP), rotenone & antimycin A and XF glycolysis stress test kit including glucose, oligomycin, 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) were obtained from Seahorse Bioscience Inc. (Billerica, MA, USA). XF24 cell culture plates, sensor cartridgeas and XF base medium were also purchased from Seahorse Bioscience Inc. Dulbecco׳s modified Eagle׳s medium-high glucose (DMEM-HG) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were procured from GIBCO (Langley, OK, USA) and plastic culture plates were manufactured by Corning Inc. (Corning, NY, USA). Unless indicated differently, all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Cell preparation

IPEC-J2 cells were obtained from GuangZhou Jennio Biotech Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). Cells were seeded in XF24 cell culture plates in 100 µL growth medium (DMEM-HG medium containing 10% FBS) and placed in 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. After cells adhere within 3 h, add 150 µL growth medium and return to 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. For optimizating cell number, 10,000, 20,000, 40,000 or 80,000 cells/well were seeded and then an optimal seeding density was used for other experiments.

2.3. Cell mito stress test assay

After a 24-h incubation, growth medium from each well were removed, leaving 50 µL of media. And cells were washed twice with 1,000 µL of pre-warmed assay medium (XF base medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate; pH 7.4) and 1,000 µL was removed as above then 475 µL of assay medium (525 µL final) was added. For the study of energy substrates on mitochondrial respiration, XF base medium (Energy-), XF base medium supplemented with individual glutmaine, glucose, sodium pyruvate or all these energy substrates (Energy+) were replaced assay medium.

Cells were incubated in 37°C incubator without CO2 for 1 h to allow to pre-equilibrate with the assay medium. Load pre-warmed oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone & antimycin A into the injector ports A, B and C of sensor cartridge, respectively. The final concentrations of injections were as follows: optimizating cell number experiment, 0.25 µM oligomycin, 1 µM FCCP, 1 µM rotenone & antimycin A; optimizating oligomycin experiment, 0, 0.25, 0.5 or 1 µM oligomycin, 1 µM FCCP, 1 µM rotenone & antimycin A; optimizating FCCP experiment, 0.5 µM oligomycin, 0, 1, 2 or 4 µM FCCP, 1 µM rotenone & antimycin A; experiment of energy substrates on mitochondrial respiration, 0.5 µM oligomycin, 1 µM FCCP, 1 µM rotenone & antimycin A.

The cartridge was calibrated by the XF24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA, USA), and the assay continued using cell mito stress test assay protocol as described by Nicholls et al. (2010). Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were detected under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin, FCCP, as well as rotenone & antimycin A. This allowed for an estimation of the contribution of individual parameters for basal respiration, proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, non-mitochondrial respiration and ATP production (Tan et al., 2015).

2.4. Glycolysis stress test assay

After a 24-h incubation, the media was changed to assay medium (XF base medium DMEM supplemented with 2 mM glutamine), and cells were incubated in a non-CO2 incubator at 37°C for 1 h before the assay. Injections of glucose (10 mM final), oligomycin (0.5 µM final) and 2-DG (100 mM final) were diluted in the assay medium and loaded into ports A, B and C, respectively. The machine was calibrated and the assay was performed using glycolytic stress test assay protocol as suggested by the manufacturer (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA, USA). ECAR was measured under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of 10 mM glucose, 0.5 µM oligomycin, and 100 mM 2-DG (Glu > Oli > 2-DG). Assay medium was injected instead of glucose, oligomycin and 2-DG serving as the control. This allowed for an estimation of the contribution of individual parameters for non-glycolytic acidification, glycolysis, glycolytic capacity, glycolytic reserve of IPEC-J2.

2.5. Data analysis

The XF mito stress test report generator and the XF glycolysis stress test report generator automatically calculate the XF cell mito stress test and XF glycolysis stress test parameters from Wave data that have been exported to Excel. Respiration and acidification rates are presented as the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments in all experiments performed with 4 to 10 replicate wells in the Seahorse XF24 analyzer. For experiment of energy substrates on mitochondrial respiration, significance level was determined by performing ANOVA on the complete data set with Tukey׳s post-hoc testing. The results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

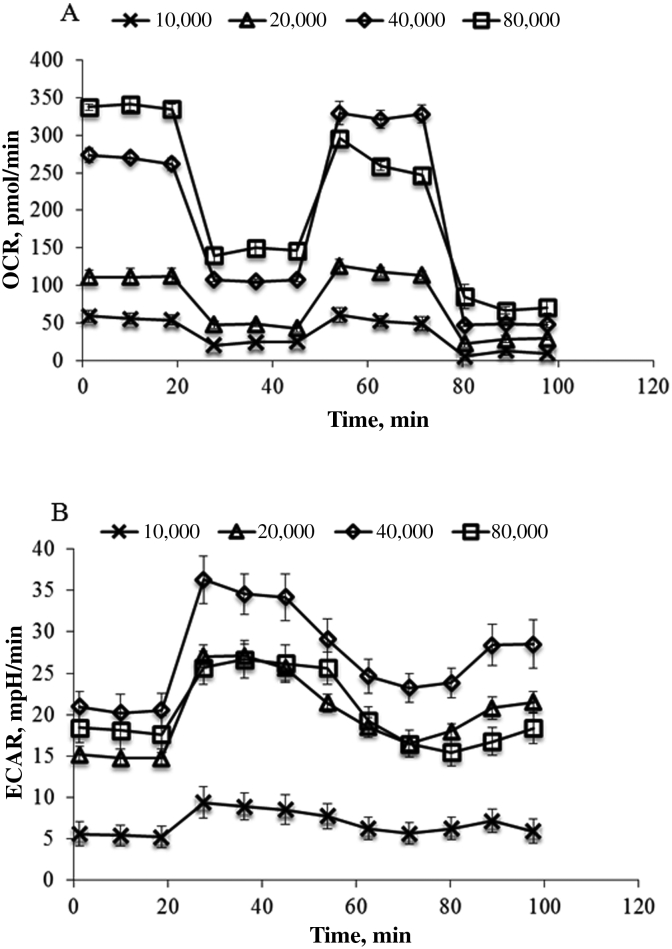

3.1. Optimization of XF assay for IPEC-J2

The seeding density and concentrations of the injection compounds were optimized. The OCR was increased with increasing cell number from 10,000 to 80,000 per well under basal condition, but begans to level off at 40,000 cells for FCCP stimulated OCR rates. For both basal and FCCP stimulated rates, the ECAR value also does not increase from 40,000 to 80,000 cells (Fig. 1). A seeding density of 40,000 cells/well was chosen for the subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1.

Optimization of cell number for measuring mitochondrial respiration of IPEC-J2. IPEC-J2 were seeded to 10,000, 20,000, 40,000 or 80,000 cells/well and incubate for 24 h. (A) Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and (B) extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin (0.25 µM), FCCP (1 µM), as well as rotenone & antimycin A (1 µM), as indicated. Each data point represents an OCR or ECAR measurement.

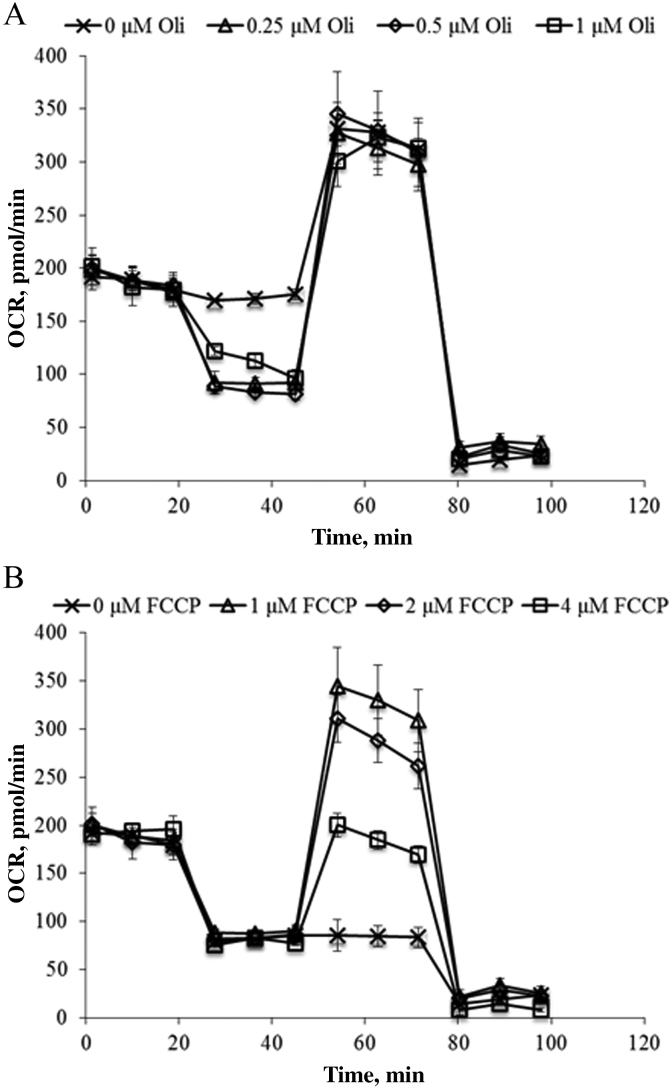

After oligomycin injection, the OCR was decreased with the increasing the concentration of oligomycin from 0 to 0.5 µM, but 1 µM did not decrease the OCR compared with 0.25 or 0.5 µM (Fig. 2A). For FCCP stimulated OCR rates, the higher peak point at 1 µM was observed and increasing the concentration of FCCP beyond 1 µM did not increase the OCR (Fig. 2B). Therefore, the optimal concentrations for oligomycin and FCCP were determined to be 0.5 and 1 µM, respectively, for the subsequent experiments.

Fig. 2.

Optimization of (A) oligomycin (Oli) and (B) carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone(FCCP) for measuring mitochondrial respiration of IPEC-J2. IPEC-J2 were seeded to 40,000 cells/well and incubate for 24 h. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin (0, 0.25, 0.5 or 1 µM), FCCP (0, 1, 2 or 4 µM), as well as rotenone & antimycin A (1 µM), as indicated. Each data point represents an OCR measurement.

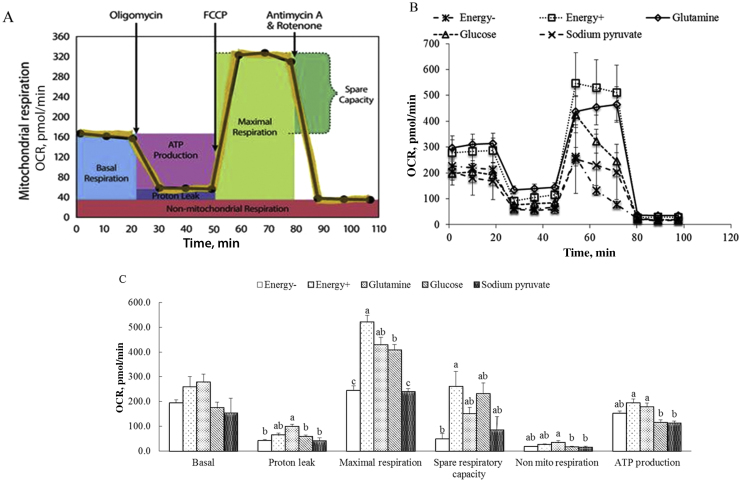

3.2. Effects of energy substrates on mitochondrial respiration of IPEC-J2

The general scheme of mitochondrial stress test is shown in Fig. 3A. Sequential injections of oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone and antimycin A measure basal respiration, ATP production, proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and non-mitochondrial respiration. Combined with the results of OCR (Fig. 3B) and individual parameters (Fig. 3C), there were no differences in OCR and all individual parameters between in base medium supplemented with glutmaine or all energy substrates (Energy+) and also between in base medium (Energy−) or supplemented with sodium pyruvate (P > 0.05). Higher proton leak and maximal respiration in glutmaine added-medium and Energy+ were observed compared with other groups (P < 0.05). The proton leak, maximal respiration, non-mitochondrial respiration and ATP production in glucose added-media were lower than Energy+ whereas the maximal respiration was higher than Energy− (P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effects of energy substrates on mitochondrial respiration of IPEC-J2. (A) Schematic of mitochondrial stress test, (B) oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and (C) individual parameters for basal respiration, proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, non-mitochondrial respiration and ATP production. IPEC-J2 were seeded to 40,000 cells/well and incubate for 24 h. Oxygen consumption rate was measured in XF base medium (Energy-), XF base medium supplemented with individual glutmaine, glucose, sodium pyruvate or all these energy substrates (Energy+) under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin (0.5 µM), FCCP (1 µM), as well as rotenone & antimycin A (1 µM), as indicated. Each data point represents an OCR measurement. Data are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 4 independent experiments. a-c Means sharing different letters differ (P < 0.05).

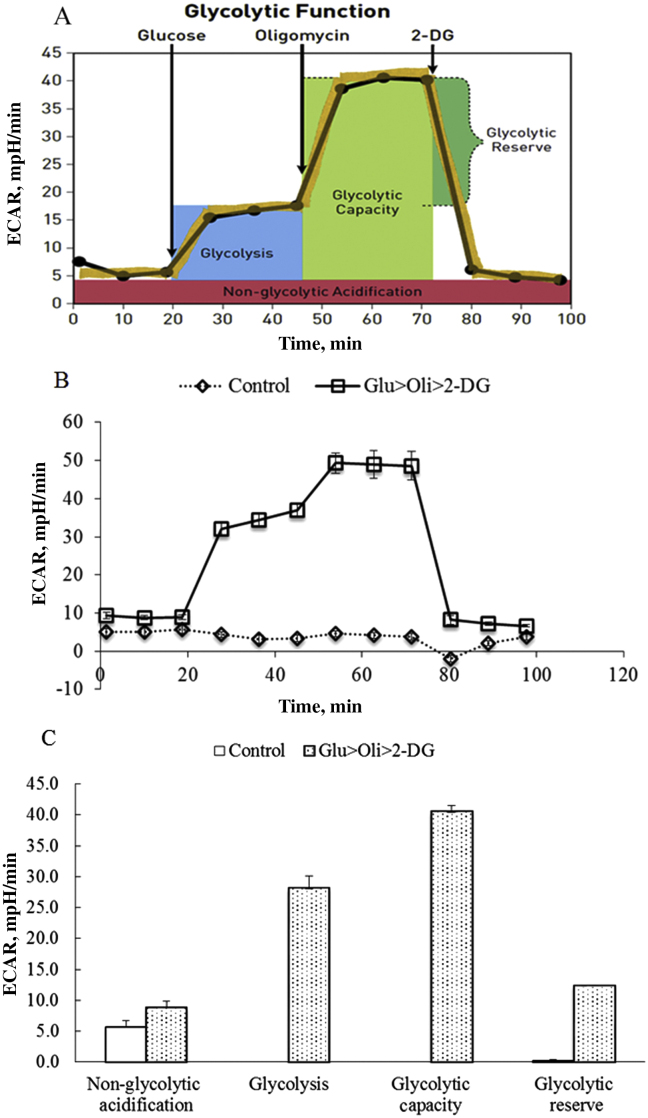

3.3. The profile of glycolysis stress test of IPEC-J2

The general scheme of glycolysis stress test is shown in Fig. 4A. Sequential injections of glucose, oligomycin and 2-DG measure glycolysis, glycolytic capacity and allow calculation of glycolytic reserve and non-glycolytic acidification. The ECAR was significantly increased after glucose injection and subsequent increase in ECAR after oligomycin injection then a decrease with 2-DG injection to wells (Fig. 4B). Correspondingly, high glucose (10 mM) induced glycolysis, the subsequent increase with oligomycin in ECAR revealed the cellular maximum glycolytic capacity, and 2-DG shut down glycolysis in IPEC-J2 (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

The profile of glycolysis stress test of IPEC-J2. (A) Schematic of glycolysis stress test, (B) extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and (C) individual parameters for non-glycolytic acidification, glycolysis, glycolytic capacity, glycolytic reserve of IPEC-J2. IPEC-J2 were seeded to 40,000 cells/well and incubate for 24 h. ECAR was measured under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of 10 mM glucose, 0.5 µM oligomycin, and 100 mM 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) (Glu > Oli > 2-DG). Assay medium was injected instead of glucose, oligomycin and 2-DG serving as the control. Each data point represents an ECAR measurement. Data are expressed as means ± SEM, n = 4 independent experiments.

4. Discussion

Extracellular flux analysis is a mainstream method for measuring mitochondrial function in cells and tissues (Salabei et al., 2014), which reports the rate of ATP production, proton leak rate, coupling efficiency, maximum respiratory rate, respiratory control ratio and spare respiratory capacity (Brand and Nicholls, 2011). Herein, we establish a method to measure mitochondrial respiratory function and profile mitochondrial function of IPEC-J2 under normal conditions using Seahorse Bioscience XF24 extracellular flux analyzer.

At first, optimization of cell seeding number should be the first experiment performed with any cell line being used in the XF system. For basal or FCCP stimulated rates, the ECAR or OCR values do not increase significantly from 40,000 to 80,000 cells, indicating that the ECAR or OCR signal have reached a plateau somewhere between 40,000 and 80,000 cells/well. Therefore, a seeding density of 40,000 was chosen for the subsequent experiments.

Secondly, the compounds injected should be optimized for the concentration that provides the maximal effect (Nicholls et al., 2010). Oligomycin, an inhibitor of ATP synthesis, is used to prevent state 3 (phosphorylating) respiration. The second injection of FCCP allows for uninhibited movement of protons across the mitochondrial inner membrane and effectively depletes the mitochondrial membrane potential. This collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential leads to an increase in oxygen consumption and allows a determination of the maximal oxygen consumption (Dranka et al., 2011). In IPEC-J2, 0.5 µM oligomycin and 1 µM FCCP were titrated to decrease OCR to a relative plateau and achieve maximal stimulation of OCR, respectively. And 1 µM rotenone & antimycin A was used to inhibit mitochondrial function with a decrease in OCR.

Accumulating evidence suggests that enterocytes may serve as energy flow sensors in the control of eating (Langhans, 2010). And glutamine, glutamate and aspartate are major fuels for mucosa and support ATP-dependent metabolic processes that glutamine accounts for about 77 and 35% of CO2 production in the fasted and fed states, respectively (Windmueller and Spaeth, 1980, Wu, 1998). It has been demonstrated that intestinal tissues preferentially derive much more energy from glutamine and glutamate than glucose (Wu et al., 1995). In agreement with this result, the higher proton leak and maximal respiration in response to glutamine than glucose were observed, confirming the relatively low oxidation rate of glucose in porcine enterocyte (Reeds et al., 2000). Wu et al. (1995) demonstrated that glucose oxidation was inhibited in the presence of glutamine, but glutamine oxidation was not altered by addition of glucose. Because of limiting feed (energy) intake during the acute phase after weaning, glutamine contributes to alleviate intestinal alterations by providing gut tissue with fuel and precursors for defense systems (Lallès et al., 2004). Madej et al. (2002) also showed that the tricarboxylic acid cycle for transformation of a-ketoglutarate was from amino acids (e.g., glutamine, glutamate) than acetyl-CoA in the porcine small intestinal epithelium during suckling–weaning transition.

Finally, the profile of glycolysis of IPEC-J2 was determined using glycolysis stress test. A major purpose of enterocyte glycolysis is to generate pyruvate, lactate, alanine and so on for the liver (Langhans, 2010). Glycolysis induced high glucose and the maximal glycolytic capacity after inhibiting oxidative phosphorylation by oligomycin in IPEC-J2 were presented. Although providing less significant oxidative fuel for the gut, glucose is the major source of pyruvate for transamination of glutamine amino nitrogen. The major proportion of the pyruvate that was derived from glucose came from glycolysis (Cremin and Fleming, 1997).

5. Conclusion

In summary, a method to measure mitochondrial respiration using extracellular flux analysis was presented. The optimal seeding density and concentrations of the injection compounds were determined to be 40,000 cells/well as well as 0.5 µM oligomycin, 1 µM FCCP and 1 µM rotenone & antimycin A, respectively. The profiles of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis confirmed that porcine enterocyte preferentially derive much more energy from glutamine than glucose. These results will provide a basis for further study of mitochondrial function and bioenergetics of the porcine small intestine.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2013CB127302), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31330075, 31372326, 31301988, 31301989) and the State Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition (2004DA125184F1401).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Brand M.D., Nicholls D.G. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem J. 2011;435(2):297–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremin J.D., Jr., Fleming S.E. Glycolysis is a source of pyruvate for transamination of glutamine amino nitrogen in jejunal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G575–G588. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.3.G575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranka B.P., Benavides G.A., Diers A.R., Giordano S., Zelickson B.R., Reily C. Assessing bioenergetic function in response to oxidative stress by metabolic profiling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51(9):1621–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacza Z., Puskar M., Figueroa J.P., Zhang J., Rajapakse N., Busija D.W. Mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase is constitutively active and is functionally upregulated in hypoxia. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31(12):1609–1615. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00754-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallès J.P., Boudry G., Favier C., Le Floc׳h N., Luron I., Montagne L. Gut function and dysfunction in young pigs: physiology. Anim Res. 2004;53(4):301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Langhans W. The enterocyte as an energy flow sensor in the control of eating. Forum Nutr. 2010;63:75–84. doi: 10.1159/000264395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madej M., Lundh T., Lindberg J.E. Activity of enzymes involved in energy production in the small intestine during suckling-weaning transition of pigs. Biol Neonate. 2002;82:53–60. doi: 10.1159/000064153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls D.G., Darley-Usmar V.M., Wu M., Jensen P.B., Rogers G.W., Ferrick D.A. Bioenergetic profile experiment using C2C12 myoblast cells. J Vis Exp. 2010;46:e2511. doi: 10.3791/2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeds P.J., Burrin D.G., Stoll B., Jahoor F. Intestinal glutamate metabolism. J Nutr. 2000;130:S978–S982. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.978S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salabei J.K., Gibb A.A., Hill B.G. Comprehensive measurement of respiratory activity in permeabilized cells using extracellular flux analysis. Nat Protoc. 2014;9:421–438. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B.E., Xiao H., Xiong X., Wang J., Li G.R., Yin Y.L. L-Arginine improves DNA synthesis in LPS-challenged enterocytes. Front Biosci. 2015;20:989–1003. doi: 10.2741/4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B.E., Yin Y.L., Kong X.F., Li P., Li X.L., Gao H.J. L-Arginine stimulates proliferation and prevents endotoxin-induced death of intestinal cells. Amino Acids. 2010;38:1227–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0334-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beers-Schreurs H.M.G., Nabuurs M.J.A., Vellenga L., Kalsbeekvandervalk H.J., Wensing T., Breukink H.J. Weaning and the weanling diet influence the villous height and crypt depth in the small intestine of pigs and alter the concentrations of short-chain fatty acids in the large intestine and blood. J Nutr. 1998;128:947–953. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.6.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaugelade P., Posho L., Darcy-Vrillon B., Bernard F., Morel M.T., Duee P.H. Intestinal oxygen uptake and glucose metabolism during nutrient absorption in the pig. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1994;207:309–316. doi: 10.3181/00379727-207-43821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li G.R., Tan B.E., Xiong X., Kong X.F., Xiao D.F. Oral administration of putrescine and proline during the suckling period improve epithelial restitution after early weaning in piglets. J Anim Sci. 2015;93(4):1679–1688. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.J., Liu W., Chen C., Yan L.M., Song J., Guo K.Y. Irradiation induced injury reduces energy metabolism in small intestine of Tibet minipigs. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windmueller H.G., Spaeth A.E. Respiratory fuels and nitrogen metabolism in vivo in small intestine of fed rats. Quantitative importance of glutamine, glutamate, and aspartate. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Knabe D.A., Yan W., Flynn N.E. Glutamine and glucose metabolism in enterocytes of the neonatal pig. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R334–R342. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.2.R334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. Intestinal mucosal amino acid catabolism. J Nutr. 1998;128(8):1249–1252. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.8.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Tan B.E., Wu M.M., Yin Y.L., Li T.J., Yuan D.X. Effects of composite antimicrobial peptides in weanling piglets challenged with deoxynivalenol: II. Intestinal morphology and function. J Anim Sci. 2013;91(10):4750–4756. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X., Yang H., Tan B., Yang C., Wu M., Liu G. Differential expression of proteins involved in energy production along the crypt-villus axis in early-weaning pig small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G229–G237. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00095.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]