Abstract

The dialogue between the mammalian conceptus (embryo/fetus and associated membranes) involves signaling for pregnancy recognition and maintenance of pregnancy during the critical peri-implantation period of pregnancy when the stage is set for implantation and placentation that precedes fetal development. Uterine epithelial cells secrete and/or transport a wide range of molecules, including nutrients, collectively referred to as histotroph that are transported into the fetal-placental vascular system to support growth and development of the conceptus. The availability of uterine-derived histotroph has long-term consequences for the health and well-being of the fetus and the prevention of adult onset of metabolic diseases. Histotroph includes numerous amino acids, but arginine plays a particularly important role as a source of nitric oxide and polyamines required for fetal-placental development in rodents, swine and humans through mechanisms that remain to be fully elucidated. Mechanisms whereby arginine regulates expression of genes via the mechanistic target of rapamycin cell signaling pathways critical to conceptus development, implantation and placentation are discussed in detail in this review.

Keywords: Amino acids, Secreted phosphoprotein 1, Pregnancy, Interferon tau, Conceptus development, Trophectoderm

1. Introduction

One׳s Health Begins In Utero! Socioeconomic, biological, and environmental factors, particularly nutrition, have an impact on the realization of a positive outcome of pregnancy. Our research focuses on fetal and neontatal development and prevention of adult onset of metabolic diseases. Epigenomics is the study of how environmental factors such as nutrition, stress and gender modify structure and expression of genes. Epigenetic modifications of the genome may adversely impact fetal growth and development and metabolic activity (the metabolome) that predisposes one to adult onset of metabolic and inflammatory diseases (e.g., obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases). The aim of this research is to increase reproductive success in food animals and reproductive health in humans, as well as enhance long-term health and productivity of adolescent and adult humans. With a projected increase in the worldwide population from the current 7.2 billion to 9.6 billion by 2050, the global food crisis will receive increased attention as physiological epigenomics and metabolomics research improves reproductive performance of food animals that underpins human health and economic status of our global community. Improved reproductive performance in food animals due to reduced embryonic losses will increase the production of animal protein for the human diet, especially for some 400 million developing children of the world who are undernourished, and thereby compromised with respect to their future health.

Embryonic mortality and the pattern of development of conceptuses are similar for pigs, sheep, cattle and goats (Bazer and First, 1983, Geisert et al., 1982a, Geisert et al., 1982b). Spherical blastocysts shed the zona pellucida, expand to large spherical blastocysts and then become tubular and finally filamentous in their morphology at they initiate implantation during pregnancy (Bazer, 2013). These dramatic changes in morphology precede initial attachment of trophectoderm to uterine luminal epithelium (LE) and initiation of a non-invasive ”central-type” implantation. It is during this period of morphological and functional transition that 30 to 40 % of the conceptuses die, with many failing to elongate and/or achieve extensive contact of trophectoderm with uterine LE for uptake of components of histotroph from the uterine lumen. Among the species of livestock, prolific pigs and ewes suffer the greatest prenatal losses due to a suboptimal intra-uterine environment which may include inadequate uterine secretions and sub-optimal nutrition for conceptuses (embryo and its extra-embryonic membranes) (Bazer et al., 2009). In pigs, the first peak of embryonic deaths occurs between days 12 and 15 of gestation and three-fourths of prenatal losses occur in the first 25 or 30 days of gestation (Bazer and First, 1983). Then, fetal losses occur between days 30 and 75 of gestation likely as a result of inadequate development of the placenta or insufficient uterine capacity for placentation that is primarily at the expense of those conceptuses that experience insufficient elongation of the trophectoderm during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy (Bazer et al., 1969a, Bazer et al., 1969b, Fenton et al., 1970, Webel and Dziuk, 1974).

Successful establishment and maintenance of pregnancy requires appropriate development of the conceptus for pregnancy recognition signaling to ensure maintenance of a functional corpus luteum (CL) to secrete progesterone (P4) required for an intrauterine environment that supports implantation, placentation and fetal-placental growth and development (Spencer et al., 2004). Interactions between the conceptus and various uterine cells, especially LE, superficial glandular epithelia (sGE) and glandular epithelia (GE), as well as stromal cells coordinate mechanisms that stimulate: 1) conceptus development, 2) uterine blood flow, 3) water and electrolyte transport, 4) maternal recognition of pregnancy, 5) transport of nutrients such as glucose and amino acids into the uterine lumen, and 6) secretion or selective transport of components of histotroph by uterine epithelia into the uterine lumen to meet the demands of the conceptus for growth and development (Bazer et al., 2012a, Bazer et al., 2012b). Conceptuses may fail to develop appropriately due to lack of response to components of histotroph or deficiencies in components of histotroph that orchestrate developmental events required for conceptus signaling for pregnancy recognition, implantation and placentation (see Fig. 1). This review focuses on amino acids in histotroph of sheep with particular emphasis on arginine (Arg), leucine (Leu), and glutamine (Gln), as well as interactions between Arg and secreted phosphoprotein 1 [SPP1, also known as osteopontin (OPN)], that activate mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) cell signaling that stimulates migration, hypertrophy and hyperplasia of cells of the conceptus (Guertin and Sabatini, 2009, Kim et al., 2010). Arg, Leu and Gln are abundant in the conceptus (Bazer et al., 2013, Wu et al., 2013a) and their concentrations in the uterine lumen increase markedly during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy (Gao et al., 2009a, Kim et al., 2013) (Fig. 2).

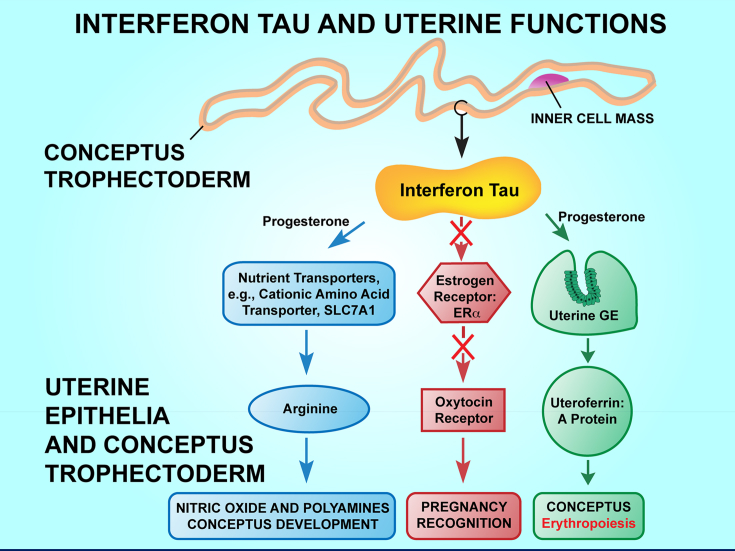

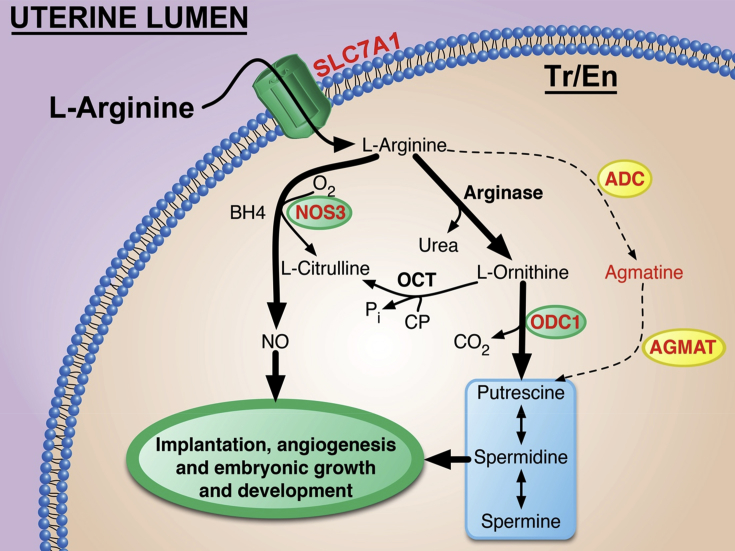

Fig. 1.

Interferon tau (IFNT) acts, with progesterone (P4) being permissive, to signal pregnancy recognition by silencing expression of estrogen receptor alpha (ESR1) and oxytocin receptor (OXTR) which abrogates the mechanism for oxytocin-induced pulsatile release of prostaglandin F2a. Therefore the ovarian corpora lutea remain functional and produce P4, the hormone of pregnancy. Interferon tau and P4-induced progestamedins act on uterine glandular epithelia for secretion of uteroferrin that stimulates erythropoiesis, while IFNT and P4-induced progestamedins act via uterine luminal epithelium and superficial glandular epithelia to increase transport of arginine to conceptus trophectoderm and uterine epithelia for metabolism to nitric oxide and polyamines essential for conceptus growth and development. SLC7A1 = solute carrier family member 7; GE = glandular epithelia.

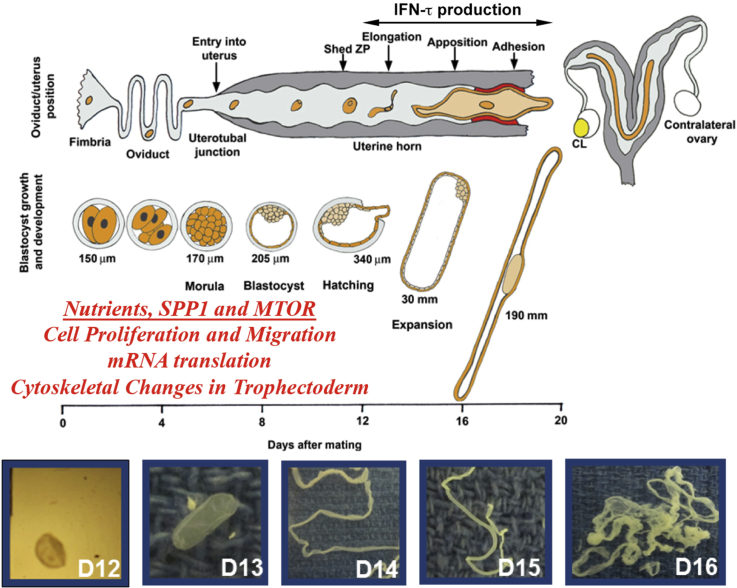

Fig. 2.

The peri-implantation of pregnancy in ewes in marked by a rapid transition of hatched blastocysts from spherical to tubular and filamentous forms in response to proteins and select nutrients secreted and/or transported into the uterine lumen. The trophectoderm cells and extra-embryonic endoderm cells undergo proliferation, migration, and cytoskeletal changes to elongate which is critical for secreting interferon tau (IFNT) the signal for pregnancy recognition, as well as implantation. Arginine and secreted phosphoprotein 1 are important for stimulating growth and development of ovine and porcine conceptuses.

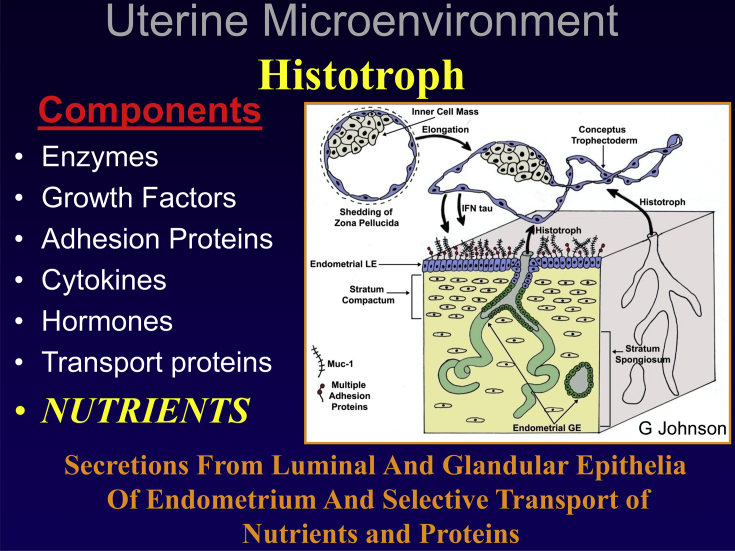

All mammalian uteri contain endometrial glands that produce/or selectively transport a complex array of proteins and related substances termed histotroph. Histotroph is a complex mixture of enzymes, growth factors, cytokines, lymphokines, hormones, transport proteins, sugars, amino acids, water, and other nutrients that affect trophectoderm development and function (Bazer, 2013). Among nutrients, amino acids play the most important roles in growth and development of the conceptus because they are essential for protein synthesis and activation of cellular functions (Kim et al., 2008, Wu, 2013a, Wu, 2013b, Wu et al., 2013b). This places amino acids at the forefront of animal health because fetal growth restriction has permanent negative impacts on neonatal adjustment to extra-uterine life, preweaning survival, postnatal growth, efficiency of feed utilization, lifetime health, tissue composition (including protein, fat, and minerals), meat quality, reproductive function, and athletic performance (Wu et al., 2006). Based on dietary needs for nitrogen balance or growth, amino acids have been traditionally classified as nutritionally essential (indispensable) or nonessential (dispensable). Nutritionally essential amino acids are those for which carbon skeletons cannot be synthesized or those which are inadequately synthesized de novo by the body to meet metabolic needs and must be provided in the diet to meet requirements (Wu et al., 2013b). Non-essential amino acids are defined as those amino acids which are synthesized de novo in adequate amounts by the body to meet requirements. Nutritionally essential amino acids are normally synthesized in adequate amounts by the organism, but must be provided in the diet to meet needs under conditions where rates of utilization are greater than rates of synthesis. Functional amino acids regulate key metabolic pathways to benefit health, survival, growth, development, lactation and reproduction of animals and humans (Wu et al., 2010). These unique nutrients include Arg, cysteine (Cys), Gln, Leu, proline (Pro) and tryptophan (Trp) which can be classified as either nutritionally essential or non-essential amino acids (Li et al., 2009, Tan et al., 2010, Tan et al., 2009, Wu, 2013b, Wu et al., 2013b). (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

The uterine microenvironment of histotroph includes various molecules that are secreted or transported into the uterine lumen to stimulate growth and development of the conceptus during the peri-implantation period. Interferon tau (IFNT) induces interferon regulatory factor 2 in uterine luminal epithelium (LE) and superficial glandular (sGE) epithelia which prevents their expression of classical interferon stimulated genes (ISGs). Rather, uterine LE/sGE express genes for nutrient transporters and other genes critical for growth and development of the conceptus. The uterine glandular epithelium (GE) and stromal cells do express classical ISGs.

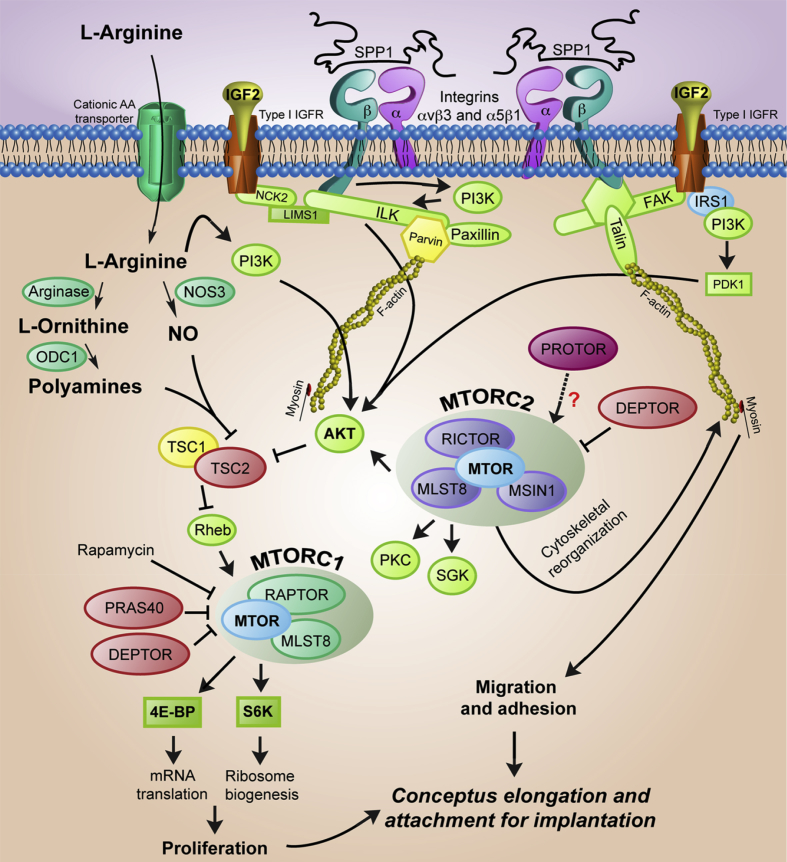

Fig. 4.

Model for induction of cell signaling for proliferation, migration, adhesion, and cytoskeletal remodeling of conceptuses via MTORC1 and MTORC2 signaling cascade. AKT1 = proto-oncogenic protein kinase 1; FAK = focal adhesion kinase; PDK1 = phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1; MTOR = mechanistic target of rapamycin; RAPTOR = regulatory-associated protein of MTOR; RICTOR = rapamycin-insensitive companion of MTOR; IGF2 = insulin-like growth factor 2; type I IGF2 = type I insulin-like growth factor receptor; ILK = integrin-linked kinases; IRS1 = insulin receptor substrate 1; PKC = protein kinase C; SGK = serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase; MLST8 = mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8; PRAS40 = proline-rich Akt/PKB substrate 40 kDa; DEPTOR = DEP domain-containing MTOR-interacting protein; MSIN1 = mammalian stress-activated MAP kinase interacting protein 1; PROTOR = protein observed with RICTOR; NCK2 = non-catalytic region of tyrosine kinase, beta; NO = nitric oxide; NOS3 = nitric oxide synthase 3; ODC1 = ornithine decarboxylase; PI3K = phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; LIMS1 = LIM and senescent cell antigen-like domains 1; S6K = S6 kinase; SPP1 = secreted phosphoprotein 1; MTORC= mammalian target of rapamycin complex; TSC = tuberous sclerosis ; 4E-BP = eIF4E binding proteins.

Fig. 5.

Arginine is transported into trophectoderm cells by the solute carrier family member 7 (SLC7A1) where it can be converted to nitric oxide (NO) by nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3) or arginine can be converted to ornithine by arginase and then ornithine is converted to putrescine by ornithine decarboxylase (ODC1). However, the sheep conceptus can also convert arginine to agmatine via arginine decarboxylase and agmatine can be converted to putrescine by agmatinase. ADC = arginine decarboxylase; BH4 = tetrahydrobiopterin; OCT = optimal cutting temperature; AGMAT = agmatinase.

Leu, Arg and Gln are of particular interest based on their roles in conceptus development. In mice, outgrowth of trophectoderm requires Leu or Arg for expanded blastocysts to exhibit motility and outgrowth of trophectoderm required for implantation (Gwatkin, 1966, Gwatkin, 1969, Martin and Sutherland, 2001, Martin et al., 2003). Leu and Arg initiate cell signaling via a serine–threonine kinase and mTOR to regulate protein synthesis and catabolism, and induce expression of genes for insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF2), nitric oxide synthases (NOS), and ornithine decarboxylase (ODC1) (Kimball et al., 1999, Murakami et al., 2004, Nielsen et al., 1995). This may allow the conceptus and uterus to coordinate differentiation of trophectoderm with development of uterine epithelia receptive to implantation. There are also differential effects of Leu, Arg and Gln on hypertrophy and hyperplasia of cells important for conceptus development during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy (Kim et al., 2011a). Physiological levels of Leu, Arg and Gln stimulate activities of mTOR and ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6) kinase, and proliferation of trophectoderm cells (Kim et al., 2013). Interestingly, the actions of Gln require the presence of physiological concentrations of glucose or fructose, supporting the view that hexosamine plays a cell signaling role in conceptus growth and development (Kim et al., 2012). Cellular events associated with elongation of ovine and porcine conceptuses during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy involve both cellular hyperplasia and hypertrophy, as well as cytoskeletal reorganization during the transition of spherical blastocysts to tubular and filamentous conceptuses (Albertini et al., 1987, Burghardt et al., 2009, Mattson et al., 1990).

Amino acids in histotroph of sheep and swine, particularly Arg, Leu, and Gln, as well as a mixture of Arg and SPP1 can activate mTOR cell signaling that stimulates migration, hypertrophy and hyperplasia of cells of the conceptus (Guertin and Sabatini, 2009, Kim et al., 2010). As noted previously, Arg, Leu and Gln are abundant in the conceptus (Bazer et al., 2013, Wu et al., 2013a) and their concentrations in the uterine lumen increase markedly during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy (Gao et al., 2009a, Kim et al., 2013). Arg is the precursor for synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) via NOS and polyamines via either the Arg : ODC1 pathway or the arginine decarboxylase (ADC) : agmatinase (AGMAT) pathway, as well as homoarginine.

2. Conceptus development and signaling for pregnancy recognition in sheep

2.1. Conceptus development in sheep

Sheep embryos enter the uterus on day 3, develop to spherical blastocysts and then transform from spherical (day 10, 0.4 mm) to tubular and filamentous conceptuses between days 12 (1 × 33 mm), 14 (1 × 68 mm) and 15 (1 × 150 to 190 mm) of pregnancy with extra-embryonic membranes extending into the contralateral uterine horn between days 16 and 20 of pregnancy (Bazer and First, 1983). Elongation of ovine conceptuses is a prerequisite for central implantation involving apposition and adhesion between trophectoderm and uterine LE and sGE, hereafter designated as LE/sGE. There is then transient loss of uterine LE allowing intimate contact between trophectoderm and uterine basal lamina adjacent to uterine stromal cells to about day 25 of pregnancy when uterine LE begins to be restored and placentation continues to day 75 of gestation. All mammalian uteri contain uterine glands that produce/or selectively transport a complex array of proteins and other molecules into the uterine lumen and this is known collectively as histotroph. Uterine glands and the molecules that they secrete or transport into the uterine lumen are essential for conceptus development (Gray et al., 2001). Components of histotroph required for elongation and development of conceptuses are transported into the uterine lumen via specific transmembrane transporters and receptors or they may be taken up by conceptus trophectoderm via pinocytosis (Bazer et al., 2008, Bazer et al., 2011, Bazer et al., 2009, Bazer et al., 2010, Spencer et al., 2007). Ewes that lack uterine glands and histotroph fail to exhibit normal estrous cycles or maintain pregnancy beyond day 14 (Gray et al., 2001).

Between days 14 and 16, binucleate cells differentiate in the trophectoderm and migrate and fuse with uterine LE to form syncytia (Guillomot et al., 1981, Wooding, 1982). Progesterone receptors (PGR) in uterine LE/sGE and GE are down-regulated by day 13 of pregnancy which is associated with loss of expression of mucin 1, transmembrane (MUC1) and onset of expression of genes considered to be critical to conceptus development and implantation including glycosylated cell adhesion molecule 1 (GlyCAM1), galectin-15 (LGALS15), integrins and SPP1 (Spencer et al., 2007). With apposition of the conceptus trophectoderm and uterine LE the filamentous ovine conceptus is immobilized in the uterine lumen and there is interdigitation of cytoplasmic projections of the trophectoderm cells and uterine epithelial microvilli to ensure maintenance of intimate contact (Guillomot et al., 1981, Wimsatt, 1950, Wooding, 1982). Apposition of trophectoderm begins proximal to the embryonic disc and then spreads toward the ends of the elongated conceptus. The uterine glands are also involved in apposition as the trophoblast develops and extends finger-like villi or papillae into the mouths of the uterine glands to absorb components of histotroph between days 15 and 20 after which time the papillae disappear (Guillomot et al., 1981, Guillomot and Guay, 1982, Wimsatt, 1950, Wooding, 1982). The ovine uterine endometrium of ewes has both aglandular caruncular and glandular intercaruncular areas (Amoroso, 1952). Synepitheliochorial placentation in sheep involves development and fusion of placental cotyledons with endometrial caruncles to form placentomes which are the primary sites of conceptus-maternal exchange for gases and nutrients, such as amino acids and glucose.

2.2. Interferon tau signaling for pregnancy recognition in ewes

During the estrous cycles of ewes, uterine LE/sGE release luteolytic pulses of prostaglandin F2α (PGF) that induces structural and functional regression of the CL or luteolysis. The uterine epithelia respond to sequential effects of P4, estradiol-17β (E2) and oxytocin (OXT) to activate the mechanism for secretion of luteolytic pulses of PGF. Progesterone stimulates accumulation of phospholipids in uterine LE/sGE and GE that liberate arachidonic acid in response to E2-induced activation of phospholipase A. The arachidonic acid released from phospholipids is metabolized via prostaglandin synthase 2 (PTGS2) and prostaglandin F synthase for secretion of PGF. On days 13 to 14 of the estrous cycle, down-regulation of expression of PGR in response to P4 allows increases in expression of receptors for E2 (ESR1) and OXT (oxytocin receptor, OXTR) which allow E2 and OXT to act on uterine LE/sGE to increase expression of ESR1 and OXTR. The pulsatile release of OXT from the posterior pituitary gland and CL induces pulsatile release of luteolytic PGF from uterine LE/sGE resulting in structural and functional demise of the CL (Bazer et al., 2011, Bazer et al., 2010).

Interferon tau (IFNT), the pregnancy recognition signal in ruminants, silences transcription of ESR1 directly which indirectly results in silencing of expression of the OXTR gene in uterine LE/sGE. This effect of IFNT abrogates development of the uterine luteolytic mechanism which prevents OXT-induced release of luteolytic pulses of PGF (Bazer et al., 2010). Silencing ESR1 expression by IFNT also prevents E2 from inducing PGR in endometrial epithelia. The absence of PGR in uterine epithelia is required for uterine LE/sGE and GE to express P4-induced, as well as P4-induced and IFNT-stimulated genes (Bazer et al., 2010).

2.3. Progesterone-induced and interferon tau – stimulated genes in ovine uterine epithelia

In addition to signaling pregnancy recognition in ruminants, IFNT, in concert with P4, regulates expression of genes in the ovine uterus in a cell-specific manner. IFNT induces uterine GE and stromal cells to express classical interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) that include, but are not limited to signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), STAT2, interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1), IRF9, interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15), myxovirus resistance 1 (MX1), 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthase 1 (OAS), and radical s-adenosyl methionine domain-containing protein 2 (RSAD2). However, there are no classical ISGs expressed by uterine LE/sGE. This is because IFNT induces expression of IRF2, a potent transcriptional repressor only in uterine LE/sGE (Bazer et al., 2010, Spencer et al., 2007). Therefore, uterine LE/sGE express novel P4-induced and IFNT stimulated genes via a PGR- and STAT1-independent cell signaling pathway(s) that is critical for implantation and establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. The alternative cell signaling pathways stimulated by IFNT in ovine uterine LE/sGE include mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, catalytic, gamma/V-AKT murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1/mechanistic target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway) (Kim et al., 2003, Platanias, 2005). This mechanism allows uterine LE/sGE in direct contact with conceptus trophectoderm to express novel genes critical to growth and development of the conceptus. Progesterone is permissive to the actions of IFNT because it down-regulates expression of PGR in the uterine LE/sGE. The absence of PGR in uterine LE/sGE removes inhibition of expression of genes regulated by a progestamedin(s) and IFNT that support implantation and conceptus development (Bazer et al., 2011). In ewes, effects of P4 appear to be mediated primarily by fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and, perhaps secondarily by hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) from uterine stromal cells that express PGR (Satterfield et al., 2008). Novel P4-induced and IFNT stimulated genes include solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 (SLC7A2), cystatin C (CST3), cathepsin L (CTSL), solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 1 (SLC2A1), hypoxia-inducible factor 1, alpha subunit (HIF2A), and LGALS15 that encode for secretory proteins and transporters that deliver molecules into the uterine lumen that are critical to conceptus development (Bazer et al., 2011, Spencer et al., 2007).

2.4. Stromal cell-derived progestamedins mediate effects of progesterone on uterine epithelia

The paradigm of down-regulation of PGR in uterine epithelia prior to implantation is common to sheep (Bazer et al., 2011), pigs (Geisert et al., 1994), rhesus monkey (Slayden and Keator, 2007), women (Kao et al., 2002) and mice (Dey et al., 2004). Therefore, progestamedins from PGR positive uterine stromal cells regulate functions of uterine LE/sGE/GE, and include fibroblast growth factor 7 (FGF7), FGF10 and HGF and they regulate function of LE/sGE and GE (Cunha et al., 2004). Fibroblast growth factor 7 and FGF10 act via fibroblast growth factor receptor FGFR2IIIb whereas the receptor for HGF is encoded by MET (HGFR). In ewes, FGF10 mRNA is abundant in uterine stromal cells during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy when circulating concentrations of P4 are high and FGF10 is also expressed by trophectoderm suggesting that FGF10 mediates placental mesenchymal–trophectodermal interactions to stimulate development of the placenta. Fibroblast growth factor 7 is expressed in the tunica media of uterine blood vessels of ewes which is consistent with its expression in spiral arteries of the primate endometrium (Chen et al., 2000a, Chen et al., 2000b). However, FGF7 is not expressed by uterine stromal cells (Chen et al., 2000a). The nonoverlapping cell-specific patterns of expression for FGF10 and FGF7 in uteri of ewes suggest that these growth factors have independent roles in uterine functions and conceptus development. In ewes, HGF is expressed by uterine stromal cells and HGFR mRNA is localized exclusively to LE/sGE and GE, as well as trophectoderm (Chen et al., 2000b). HGF may stimulate epithelial morphogenesis and differentiated functions required for establishment and maintenance of pregnancy, conceptus implantation and placentation (Uehara et al., 1995).

3. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen

Nutrients stimulate the mTOR nutrient sensing cell signaling pathway to increase translation of mRNAs critical to blastocyst/conceptus development, including IGF2 (Martin and Sutherland, 2001). Cell signaling via mTOR stimulates cell migration and invasion, as well as cell growth and proliferation in different cell types (Liu et al., 2008). The mTOR null mice die shortly after implantation due to impaired cell proliferation and hypertrophy in both the embryonic disc and trophoblast (Murakami et al., 2004). In mice, Leu or Arg is required for expanded blastocysts to exhibit motility and outgrowth of trophectoderm required for implantation (Gwatkin, 1969, Martin et al., 2003, Zeng et al., 2008). These amino acids regulate motility and outgrowth of trophectoderm through activation of serine/threonine kinase mTOR cell signaling which activates Rac-1, a member of the Rho GTPase family. Increased mTOR signaling also stimulates protein synthesis and expression of IGF2, NOS and ODC1 mRNAs (Martin and Sutherland, 2001, Martin et al., 2003). The mTOR cell signaling pathway is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase located downstream of PI3K that controls cell growth and proliferation through regulation of mRNA translation for protein synthesis and cell proliferation (Wullschleger et al., 2006). Cellular events directly controlled by the mTOR pathway include mRNA translation, ribosome synthesis, expression of metabolism-related genes, autophagy and cytoskeletal reorganization (Kim et al., 2002).

Arg can be used for protein synthesis. It can also be used for the production of NO by NOS, polyamines via either the argininase (ARGI/II) and ODC1 or ADC and AGMAT pathways within the pregnant uterus (Wang et al., 2014a, Wu et al., 2009) and agamatine itself (Wang et al., 2014a). Results of systematic studies of temporal and cell-specific changes in expression of transporters for glucose and amino acids, their regulation by P4 and/or IFNT, changes in expression of NOS isoforms, ODC and related proteins, as well as components of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (MTORC1) and mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (MTORC2) cell signaling in ovine uteri and conceptuses have been published (Gao et al., 2009a, Gao et al., 2009b, Gao et al., 2009c, Gao et al., 2009d, Gao et al., 2009e, Gao et al., 2009f; Kim et al., 2011a, Kim et al., 2011b, Kim et al., 2011c). Results of those studies revealed that: 1) total recoverable glucose, Arg, Leu, Gln, glutathione, calcium and sodium are more abundant in uterine fluids of pregnant than cyclic ewes between days 10 and 16 after onset of estrus or mating; 2) uteri and conceptuses express tissue and cell-specific facilitative and sodium-dependent transporters for glucose, as well as for cationic, acidic and neutral amino acids, some of which are regulated by P4 or P4 and IFNT; 3) transport of Arg into the uterine lumen and uptake by conceptuses occurs via system y+ (SLC7A1, SLC7A2, SLC7A3) cationic amino acid transporters; 4) NOS1 and ODC1 are most abundant in uterine LE/sGE while NOS3 is most abundant in trophectoderm and extra-embryonic endoderm of conceptuses; 5) expression of GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1, the key enzyme for synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin, a cofactor for NO production), ODC1 and NOS1 is more abundant in conceptuses than endometrial cells; and 6) P4 stimulates expression of NOS1 and GCH1, while IFNT inhibits expression of NOS1. Further, components of both the MTORC1 and MTORC2 cell signaling pathways [MTOR, MTOR associated protein LST8 (LST8)], mitogen-activated protein kinase-associated protein 1 (MAPKAP1), regulatory associated protein of MTOR (RAPTOR), rapamycin-insensitive companion of MTOR (RICTOR), tuberous sclerosis 1 (TSC1), tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2), RAS homolog enriched in brain (RHEB) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4e-binding protein 1 (EIF4EBP1) are localized to uterine LE/sGE, GE and stromal cells, as well as trophectoderm and extra-embryonic endoderm of conceptuses between days 13 and 18 of pregnancy. The abundance of FRAP1, RAPTOR, RICTOR, TSC1 and TSC2 mRNAs in endometria are not affected by pregnancy status or day of the estrous cycle or pregnancy. However, expression of LST8, MAPKAP1, RHEB and EIF4EBP1 mRNAs increases in uterine epithelia during early pregnancy and expression of RHEB and EIF4EBP1 mRNAs is induced by P4 and further stimulated by IFNT in uterine epithelia. Importantly, mTOR is abundant in the cytoplasm and phosphorylated mTOR is very abundant in the nuclei of ovine trophectoderm cells and extra-embryonic endoderm. Further, the abundance of RICTOR, RHEB and EIF4EBP1, as well as RHEB proteins increase in endometria during the period of rapid conceptus growth and development during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy. These results suggest differential effects of MTORC1 and MTORC2 on elongation of ovine conceptuses and they are supported by results from in vitro studies using ovine trophectoderm (oTr) cells. Those studies indicated that: 1) Arg activates mTOR cell signaling and phosphorylation of RPS6; 2) Arg, Leu and glucose increase phosphorylation of V-AKT murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (AKT1), glycogen synthase kinase 3-beta (GSK3B), mTOR and RPS6 kinase (RPS6K) proteins; 3) Arg increases the abundance of pRPS6K and pRPS6 in the cytoplasm of oTr cells; and 4) cell proliferation is independent of NOS, but dependent on production of polyamines (Kim et al., 2010).

The mTOR signaling pathway has been linked to elongation of conceptus trophectoderm in sheep. For ovine conceptus development during implantation and placentation, the binding of SPP1 to integrins to alter the cell cytoskeleton, along with the associated effects of integrin activation by SPP1 binding and Arg on cell proliferation, are proposed to stimulate remodeling of trophectoderm for elongation and adherence to uterine LE/sGE via cytoskeletal reorganization that facilitates cell motility, stabilizes adhesion, and collectively activates mTOR signaling pathways mediated by AKT1, TSC1/2 and MTORC1 (cell proliferation and mRNA translation), as well as MTORC2 (cell migration, cell survival and cytoskeletal organization). For ovine trophectoderm cells, SPP1 binds αvβ3 and α5β1 integrins to induce focal adhesion assembly, a prerequisite for adhesion and migration of trophectoderm through activation of: 1) RPS6K via crosstalk between mTOR and MAPK pathways; 2) mTOR, PI3K, MAPK3/MAPK1 (ERK1/2) and MAPK14 (p38) signaling to stimulate migration of trophectoderm cells; and 3) focal adhesion assembly and myosin II motor activity to induce migration of trophectoderm cells. These cell signaling pathways, acting in concert, mediate adhesion, migration and cytoskeletal remodeling of ovine trophectoderm cells essential for expansion and elongation of conceptuses and attachment to uterine LE for implantation (Kim et al., 2010).

4. Arginine and development of the ovine conceptus

The abundance of Arg increases approximately 8-fold in the ovine uterine lumen between days 10 and 15 of pregnancy and is involved in several metabolic pathways (Gao et al., 2009a, Gao et al., 2009b, Gao et al., 2009c). This increase in Arg in the uterine lumen is likely associated with the biosynthesis of NO and polyamines critical to the morphological transition of ovine conceptuses from the spherical to filamentous forms and signaling for pregnancy recognition by IFNT from conceptus trophectoderm. Arg is also converted to agmatine by ADC and agmatine is converted to putrescine by AGAMAT in the uterus and conceptus trophectoderm to generate polyamines or agmatine may have direct effects on the uterus or conceptus (Wang et al., 2014a). In order to assess the importance of genes associated with Arg, we conducted in utero morpholino anti-sense oligonucleotide (MAO) loss-of-function studies to block translation of mRNAs for: 1) SLC7A1, the primary transporter for Arg into conceptus trophectoderm; 2) ODC1, the rate limiting enzyme in the pathway whereby Arg is converted to polyamines (Arg to ornithine by arginase [ARGI/II] and ornithine to polyamines by ODC1); and 3) nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3), the primary NOS isoform in ovine conceptus trophectoderm for production of NO and citrulline. The use of MAO in vivo to target knockdown of mRNA translation in conceptuses is unique in that only trophectoderm cells of the conceptuses take up the MAO while uterine epithelial cells do not take up MAO and are, therefore, unaffected with respect to mRNA translation (Wang et al., 2014a, Wang et al., 2014b).

4.1. Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide knockdown of translation of SLC7A1 mRNA in ovine conceptus trophectoderm

The MAO knockdown of SLC7A1 in the uterine lumen of pregnant ewes did not affect expression of SLC7A1 mRNA or protein in the uterus or the amount of Arg in the uterine lumen. However, MAO-SLC7A1 conceptuses had significantly less Arg, citrulline, ornithine, ODC1 and NOS3 as compared to MAO-control conceptuses (Wang et al., 2014b). In contrast to the conceptus, there was significantly more citrulline in the uterine lumen of MAO-SLC7A1 ewes perhaps due to less Arg being metabolized by either NOS3 or the arginase-ODC1 pathway, and Arg may be converted into citrulline in the conceptus or peptidylarginine deiminase may catalyze conversion of protein-bound Arg to citrulline. Since amino acids in histotroph are mainly transported from uterine LE/sGE into the lumen, and citrulline is generated when Arg is metabolized by NOS3 to generate NO, the increase in citrulline may also reflect a compensatory increase in NO production in uterine epithelia and/or endothelial cells for regulation of angiogenesis and uterine blood flow. There was a significant decrease in agmatine in the uterine lumen and conceptuses indicative of disruption of the alternative pathway for polyamine biosynthesis via ADC and AGMAT which suggests a critical role for ADC in Arg catabolism and agmatine production in ovine conceptuses. Thus, SLC7A1 is critical to transport of Arg into conceptus trophectoderm for synthesis of polyamines for proliferation and migration of conceptus trophectoderm in support of elongation and secretion of IFNT. The MAO-SLC7A1 conceptuses did not elongate normally and were fragmented whereas the MAO control conceptuses were morphologically and functionally normal filamenous conceptuses. The MAO-SLC7A1 conceptuses had significant reductions in Arg transport, ODC1 and NOS3 proteins and Arg-related amino acids (citrulline and ornithine) and polyamines. However, there was no evidence for MAO-SLC7A1 conceptuses having compensatory increases in Arg precursors [Gln and glutamate (Glu)], NOS isoforms (NOS1 and NOS2) or alternative pathways for polyamine biosynthesis via ADC and AGMAT in an attempt to rescue conceptus development. The total amount of IFNT in uterine flushings from MAO-SLC7A1 treatment was significantly less than for MAO-control conceptuses (Wang et al., 2014b). Relevant to that finding, available evidence suggests that Arg itself stimulates secretion of IFNT by ovine trophectoderm cells (Wang et al., 2015a).

4.2. Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide knockdown of translation of nitric oxide synthases 3 mRNA in ovine conceptus trophectoderm

Nitric oxide regulates early-stage embryonic development in mice (Chen et al., 2001, Tranguch et al., 2003) and humans (Lipari et al., 2009). Nitric oxide synthases 3 mRNA and protein are abundant in trophectoderm and endoderm of peri-implantation ovine conceptuses, whereas NOS1 mRNA and protein are expressed very weakly (Gao et al., 2009e). Therefore, we used MAO knockdown of translation of NOS3 mRNA in ovine conceptus trophectoderm to determine functional roles of NOS3 in NO synthesis from Arg in conceptus development (Wang et al., 2014c). The deficiency of NO in trophectoderm of MAO-NOS3 conceptuses delayed development as conceptuses were elongated, but smaller, thinner and disorganized compared to MAO-control conceptuses. However, there was no effect of loss of function of NOS3 protein on IFNT production. Interestingly, SLC7A1 protein was less abundant in MAO-NOS3 conceptuses, but ODC1 protein was similar for MAO control and MAO-NOS3 conceptuses which suggests cross-talk between the Arg transporter SLC7A1 and NOS3 at the protein level. Amounts of Arg, Gln and Glu in the uterine lumen were not affected by knockdown of NOS3 protein in conceptuses; however, there was a significant increase in citrulline and a significant decrease in ornithine in the uterine lumen of MAO-NOS3 ewes. Citrulline, a co-product of NOS, was less abundant in conceptuses. The significant increase in citrulline and significant decrease in ornithine in the uterine lumen of MAO-NOS3 ewes may result from: 1) increased secretion of citrulline into the uterine lumen and/or a reduction in its uptake by the conceptus; 2) a decrease in secretion of ornithine into the uterine lumen; or 3) increased uptake of citrulline by the conceptus and/or increased catabolism of ornithine through the ornithine aminotransferase pathway in uterine LE/sGE (Wu and Morris, 1998). The decreases in Arg, ornithine, Gln and Glu in MAO-NOS3 conceptuses suggests disruption of pathways for synthesis or transport of those amino acids in the absence of NO. The localization of NOS3 primarily in membrane-bound caveolae may affect the transport of basic, neutral, and acidic amino acids by conceptus trophectoderm (Poulin et al., 2012). There was an increase in agmatine in the uterine lumen and conceptuses of MAO-NOS3 conceptuses that may account for the smaller and thinner, but elongated MAO-NOS3 conceptus phenotype that produced IFNT. These results indicate that NO and/or downstream pathways such as the synthesis of polyamines (Wu, 2013a) are important for normal growth and development of ovine conceptuses.

4.3. Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide knockdown of translation of ornithine decarboxylase mRNA in ovine conceptus trophectoderm

The in vivo MAO knockdown of translation of mRNA for ODC1 in ovine conceptus trophectoderm resulted in one-half of the conceptuses being morphologically and functionally normal and the other one-half being abnormal. MAO-ODC1 conceptuses with a normal phenotype expressed significantly more ADC/AGMAT mRNA and protein that compensated for loss of ODC1-dependent synthesis of polyamines from Arg. Although the majority of polyamine synthesis may be via the ODC1-dependent pathway, the ADC/AGMAT pathway is a complimentary pathway for production of polyamines required for development of mammalian conceptuses. Polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine) are classical products of catabolism of Arg that are critical for placental growth in mammals (Wu et al., 2009); however, agmatine is also a product of Arg metabolism in uteri of pregnant sheep (Wang et al., 2014a). Along with insulin-like growth factors (IGF), vascular endothelial growth factors and other growth factors, NO and polyamines are crucial for angiogenesis, embryogenesis, placental growth, utero-placental blood flows, and transfer of nutrients from mother to her fetuses, as well as fetal-placental growth and development (Wu et al., 2006, Wu and Meininger, 2009). In sheep, ODC1 is the rate-controlling enzyme for classical de novo biosynthesis of polyamines; but metabolism of Arg to agmatine and polyamines via ADC and AGMAT was only recently discovered for sheep conceptuses (Wang et al., 2014a). We discovered that the functional ADC/AGMAT pathway for synthesis of polyamines in mammalian reproductive tissue can compensate for loss of ODC1 activity to assure survival and development of some conceptuses. Agmatine itself has many functions that may be important for reproduction, but there are no results to define its role in the pregnant uterus.

Exogenous agmatine has neuroprotective effects in animal models of ischemia and neurotrauma and it acts via IRAS (imidazoline receptors) to stimulate synthesis of eicosanoids (prostaglandins, leukotrienes, thromboxanes, prostacyclins) that enhance cell migration. Prostaglandins secreted by epithelial and stromal cells of the uterus effect expression of genes critical to elongation and implantation of the ovine conceptus (Dorniak et al., 2013, Dorniak et al., 2012). Synthesis, metabolism and function of agmatine in animal tissues have not been elucidated (Molderings and Haenisch, 2012), but there is little information on concentrations of agmatine in animal cells, tissues, or uterine secretions (Dai et al., 2014). Agmatine is formed in mitochondria, and arginase II and mitochondrial NOS (mtNOS) differ from cytosolic forms (Lacza et al., 2003). The NO formed in mitochondria may modulate respiratory rate and ATP synthesis by inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase (Giulivi, 1998) that would otherwise lead to formation of peroxynitrite-induced apoptosis (Ghafourifar et al., 1999). Synthesis of agmatine requires transport of Arg into mitochondria in kidney and brain by an energy-independent mechanism (Dolinska and Albrecht, 1998).

4.4. Arginine and secreted phosphoprotein 1 alter cytoskeleton of trophectoderm cells

Arg and SPP1 are multifunctional molecules that increase significantly in ovine uterine histotroph during early pregnancy. Therefore, we conducted in vitro experiments using our established ovine trophectoderm cell line (oTr1) to determine their individual and synergistic effects on proliferation and cytoskeletal organization. Arg stimulates a significant increase in proliferation of oTr1 cells whereas SPP1 has no effect. However, there is an additive effect on oTr1 cell proliferation when Arg was added to the culture medium along with SPP1. This additive effect is mediated through cooperative activation of the 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1)-Akt/PKB-tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2)-MTORC1 cell signaling cascade. Thus SPP1 affects the shape and spreading of oTr1 cells, while Arg increases the proliferation and abundance of cytoskeleton proteins (e.g., tubulin) to cooperatively increase proliferation and size of oTr1 cells. These effects of Arg and SPP1 are considered critical to migration and attachment of oTr1 cells for implantation via mechanisms related to MTORC2 and cytoskeletal reorganization during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy in sheep (Wang et al., 2015b).

4.5. Dietary supplementation with arginine and reproductive performance

The unusually high abundance of Arg in porcine allantoic fluid during early pregnancy (Wu and Morris, 1998) was the basis for a study by Mateo et al. (2007) to determine the effects of dietary supplementation of Arg on reproductive performance of gilts. Dietary supplementation with 0.83% Arg (as 1.0% Arg-HCl; 16.6 g Arg/sow per day) between days 30 and 114 of gestation was based on Arg kinetics and concentrations in plasma (Wu et al., 2013a). The dietary supplement with Arg increased the number of live-born piglets by 2 per litter and litter birth-weight by 24% (Mateo et al., 2007). Dietary supplementation with Arg between days 22 and 114 of gestation increased placental weights (16%), live-born piglets per litter (1.1) and litter birth weights for live-born piglets by 1.7 kg (Gao et al., 2012). Dietary supplementation with 1% Arg to gilts and sows between days 14 and 28 of gestation also increased the number of live-born piglets by approximately 1 (Campbell,, Ramaekers et al., 2006). Another study compared dietary supplementation with 0.4 or 0.8% Arg between days 14 and 25 of gestation and found a 21 to 34% increase in placental weights and an increase of 2 viable fetuses (Li et al., 2011). Supplementation of the diet of gilts with 1% Arg between days 14 and 28 of gestation increased litter size by 3.7 on day 70 of gestation in superovulated gilts (Bérard and Bee, 2010). Supplementing 1% Arg to gilts beginning on day 17 of gestation for 16 days increased litter size by 1.2 (De Blasio et al., 2009). Finally, dietary supplementation with 0.83% Arg between days 90 and 114 of gestation increased average birth weight of live-born piglets by 16% (Wu et al., 2012). There are also fewer low-birth-weight piglets when the diet of gilts and sows is supplemented with Arg (Wu et al., 2011a, Wu et al., 2010, Wu et al., 2011b).

Arg and its precursor (citrulline) are abundant in ovine uterine fluid (Gao et al., 2009f) and allantoic fluid (Kwon et al., 2003) during early to mid-gestation, and intravenous administration of Arg improves embryonic survival in pregnant ewes (Luther et al., 2008). Increasing utero-placental blood flow by administering 0, 75, or 150 mg/d sildenafil citrate (Viagra) from days 28 to 115 of gestation to underfed (50% of National Research Council [NRC] requirements) or adequately fed ewes (100% of NRC requirements) enhanced fetal growth in ewes (Satterfield et al., 2010). On day 115, concentrations of amino acids and polyamines in maternal plasma and conceptuses were lower in underfed than adequately-fed ewes. However, treatment of ewes with Viagra increased amino acids and polyamines in amniotic and allantoic fluids and fetal serum, and fetal weights in underfed ewes without affecting maternal body weights (Satterfield et al., 2010). The intravenous administration of Arg also prevents intra-uterine growth restricted (IUGR) in underfed ewes (Lassala et al., 2010). The administration of Arg to underfed ewes increased concentrations of Arg in maternal plasma (69%), fetal brown adipose tissue mass (48%), and birth weights of lambs by 21%, as compared to saline-infused underfed ewes (Satterfield et al., 2012). Similar results were observed for diet-induced obese ewes (Satterfield et al., 2012). Furthermore, intravenous administration of Arg (345 µmol Arg-HCl per kg BW three times daily) between days 100 and 121 of gestation reduced the percentage of lambs born dead by 23%, increased the percentage of lambs born alive by 59%, and enhanced birth weights of quadruplets by 23%, without affecting maternal body weight (Lassala et al., 2011).

Arg as a dietary supplement for pregnant rats also increases the numbers of implantation sites and litter size by approximately three (Zeng et al., 2012, Zeng et al., 2008). When compared with rats in the isonitrogenous control group (2.2% L-alanine), litter size in rats was increased in response to dietary supplementation with 1.3% L-Arg-HCl throughout pregnancy (14.5 vs. 11.3) or during the first 7 days of pregnancy (14.7 vs. 11.3) (Zeng et al., 2008). Concentrations of nitric-oxide metabolites, Arg, Pro, Gln, and ornithine were higher, but urea levels were lower, in serum of Arg-supplemented rats, compared with control rats. These results indicate that dietary Arg supplementation enhances embryonic survival and increases litter size. The underlying mechanisms involve activation of the PI3K/PKB/MTOR signaling pathway (Zeng et al., 2013).

Women with IUGR fetuses at week 33 of gestation were given daily intravenous infusion of Arg (20 g/d) for 7 days which increased birth weight at term (week 39) by 6.4% (Xiao and Li, 2005). Treatment of women with an IUGR fetus with Arg was effective in reducing placental apoptosis and improving fetal growth and development (Shen and Hua, 2011). Compared with the control group, Arg administration reduced the level of Bax (an apoptotic protein) in the placenta, increased average birth weight by approximately 53 g, and decreased the incidence of IUGR newborns (25 vs. 50%). Finally, a recent meta-analysis of data collected from seven registered clinical trials involving 916 patients revealed that Arg supplementation reduces diastolic blood pressure and prolongs pregnancy in patients with gestational hypertension with or without proteinuria (Gui et al., 2014). Thus Arg holds great promise to ameliorate preeclampsia in human pregnancy.

5. Conclusions

Progesterone and IFNT regulate expression of genes in uterine LE/sGE responsible for transport of nutrients into the uterine lumen to support growth and development of the conceptus. Among those genes are those for transport of Arg into the uterine lumen and then into conceptus trophectoderm. Arg can then be metabolized to NO and polyamines which are important for vascularization and blood flow to the pregnant uterus and conceptus, as well as polyamines which are critical to growth and development of the conceptus. The consequences of knockdown of ODC1 allowed us to discover the ADC/AGMAT pathway as an alternative pathway for production of polyamines. Finally, knockdown of translation of mRNAs for NOS3 and SLC7A1 adversely affects conceptus development and confirms the importance of Arg transporters, as well as the pathways whereby Arg is metabolized to key molecules having direct effects to enhance survival, growth and development of ovine conceptuses, as well as conceptuses of other species.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Acknowledgments

Research in our laboratories was supported by National Research Initiative Competitive Grants from the Animal Reproduction Program (2008-35203-19120, 2009-35206-05211, 2011-67015-20067, and 2011-67015-20028) and Animal Growth & Nutrient Utilization Program (2008-35206-18764) of the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and Texas A&M AgriLife Research (H-8200). The important contributions of our graduate students and colleagues in this research are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Association of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine.

References

- Albertini D.F., Overstrom E.W., Ebert K.M. Changes in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton during preimplantation development of the pig embryo. Biol Reprod. 1987;37:441–451. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod37.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoroso E.C. Placentation. In: Parkes A.S., editor. 3rd ed. vol. 2. Longmans Green; London: 1952. pp. 127–311. (Marshall׳s physiology of reproduction). [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W. Pregnancy recognition signaling mechanisms in ruminants and pigs. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2013;4:23. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Burghardt R.C., Johnson G.A., Spencer T.E., Wu G. Interferons and progesterone for establishment and maintenance of pregnancy: interactions among novel cell signaling pathways. Reprod Biol. 2008;8:179–211. doi: 10.1016/s1642-431x(12)60012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Robison O.W., Clawson A.J., Ulberg L.C. Uterine capacity at two stages of gestation in gilts following embryo superinduction. J Anim Sci. 1969;29:30–34. doi: 10.2527/jas1969.29130x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Clawson A.J., Robison O.W., Ulberg L.C. Uterine capacity in gilts. J Reprod Fertil. 1969;18:121–124. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0180121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., First N.L. Pregnancy and parturition. J Anim Sci. 1983;57(Suppl. 2):425–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Kim J., Song G., Ka H., Wu G., Johnson G.A. Roles of selected nutrients on development of the conceptus during pregnancy. Soc Reprod Fertil. 2013;68(Suppl.):159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Satterfield M.C., Song G. Modulation of uterine function by endocrine and paracrine factors in ruminants. Anim Reprod. 2012;9:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Kim J., Song G., Satterfield M.C., Johnson G.A., Burghardt R.C. Uterine environment and conceptus development in ruminants. Anim Reprod. 2012;9:297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Burghardt R.C. Uterine receptivity to implantation of blastocysts in mammals. Front Biosci Sch Ed. 2011;3:745–767. doi: 10.2741/s184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Burghardt R.C., Wu G. Comparative aspects of implantation. Reproduction. 2009;138:195–209. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer F.W., Wu G., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Burghardt R.C., Bayless K. Novel pathways for implantation and establishment and maintenance of pregnancy in mammals. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16:135–152. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gap095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bérard J., Bee G. Effects of dietary l-arginine supplementation to gilts during early gestation on foetal survival, growth and myofiber formation. Animal. 2010;4:1680–1687. doi: 10.1017/S1751731110000881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt R.C., Burghardt J.R., Taylor J.D., 2nd, Reeder A.T., Nguen B.T., Spencer T.E. Enhanced focal adhesion assembly reflects increased mechanosensation and mechanotransduction at maternal-conceptus interface and uterine wall during ovine pregnancy. Reproduction. 2009;137:567–582. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. Pork CRC – NZ Seminar Series: Arginine and reproduction. Available from:: http://www/nzpib.co.nz.

- Chen C., Spencer T.E., Bazer F.W. Fibroblast growth factor-10: a stromal mediator of epithelial function in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:959–966. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.3.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Spencer T.E., Bazer F.W. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor c-met in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1844–1850. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.W., Jiang W.S., Tzeng C.R. Nitric oxide as a regulator in preimplantation embryo development and apoptosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1163–1171. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha G.R., Cooke P.S., Kurita T. Role of stromal-epithelial interactions in hormonal responses. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67:417–434. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z., Wu Z., Wang J., Wang X., Jia S., Bazer F.W. Analysis of polyamines in biological samples by HPLC involving pre-column derivatization with o-phthalaldehyde and N-acetyl-L-cysteine. Amino Acids. 2014;46:1557–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1717-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Blasio M., Roberts C., Owens J. 2009. Effect of dietary arginine supplementation during gestation on litter size of gilts and sows.http://www.australianpork.com.au Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Dey S.K., Lim H., Das S.K., Reese J., Paria B.C., Daikoku T. Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:341–373. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinska M., Albrecht J. L-arginine uptake in rat cerebral mitochondria. Neurochem Int. 1998;33:233–236. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(98)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorniak P., Bazer F.W., Spencer T.E. Physiology and endocrinology symposium: biological role of interferon tau in endometrial function and conceptus elongation. J Anim Sci. 2013;91:1627–1638. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorniak P., Bazer F.W., Wu G., Spencer T.E. Conceptus-derived prostaglandins regulate endometrial function in sheep. Biol Reprod. 2012;87(9):1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.100487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton F.R., Bazer F.W., Robison O.W., Ulberg L.C. Effect of quantity of uterus on uterine capacity in gilts. J Anim Sci. 1970;31:104–106. doi: 10.2527/jas1970.311104x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Wu G., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Li X., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. I. Amino acids, glucose, and ions in uterine lumenal flushings of cyclic and pregnant ewes. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:86–93. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.071597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Wu G., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. ii. glucose transporters in the uterus and peri-implantation conceptuses. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:94–104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.071654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Wu G., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. III. Cationic amino acid transporters in the ovine uterus and peri-implantation conceptuses. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:602–609. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Wu G., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. IV. Expression of neutral and acidic amino acid transporters in ovine uteri and peri-implantation conceptuses. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:1196–1208. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Wu G., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. V. Nitric oxide synthase, GTP cyclohydrolase, and ornithine decarboxylase in ovine uteri and peri-implantation conceptuses. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:67–76. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.075473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H., Wu G., Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. VI. Expression of FK506-binding protein 12-rapamycin complex-associated protein 1 (FRAP1) and regulators and effectors of mTORC1 and mTORC2 complexes in ovine uteri and conceptuses. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:87–100. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.076257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K., Jiang Z., Lin Y., Zheng C., Zhou G., Chen F. Dietary L-arginine supplementation enhances placental growth and reproductive performance in sows. Amino Acids. 2012;42:2207–2214. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0960-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisert R.D., Renegar R.H., Thatcher W.W., Roberts R.M., Bazer F.W. Establishment of pregnancy in the pig: I. Interrelationships between preimplantation development of the pig blastocyst and uterine endometrial secretions. Biol Reprod. 1982;27:925–939. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod27.4.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisert R.D., Brookbank J.W., Roberts R.M., Bazer F.W. Establishment of pregnancy in the pig: II. Cellular remodeling of the porcine blastocyst during elongation on day 12 of pregnancy. Biol Reprod. 1982;27:941–955. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod27.4.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisert R.D., Pratt T.N., Bazer F.W., Mayes J.S., Watson G.H. Immunocytochemical localization and changes in endometrial progestin receptor protein during the porcine oestrous cycle and early pregnancy. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1994;6:749–760. doi: 10.1071/rd9940749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafourifar P., Schenk U., Klein S.D., Richter C. Mitochondrial nitric-oxide synthase stimulation causes cytochrome c release from isolated mitochondria. Evidence for intramitochondrial peroxynitrite formation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31185–31188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulivi C. Functional implications of nitric oxide produced by mitochondria in mitochondrial metabolism. Biochem J. 1998;332(Pt 3):673–679. doi: 10.1042/bj3320673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C.A., Bazer F.W., Spencer T.E. Uterine glands: developmental biology and function during pregnancy. ARBS Annu Rev Biomed Sci. 2001;3:85–126. [Google Scholar]

- Guertin D.A., Sabatini D.M. The pharmacology of mTOR inhibition. Sci Signal. 2009;2:e24. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.267pe24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui S., Jia J., Niu X., Bai Y., Zou H., Deng J. Arginine supplementation for improving maternal and neonatal outcomes in hypertensive disorder of pregnancy: a systematic review. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2014;15:88–96. doi: 10.1177/1470320313475910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillomot M., Flechon J.E., Wintenberger-Torres S. Conceptus attachment in the ewe: an ultrastructural study. Placenta. 1981;2:169–182. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(81)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillomot M., Guay P. Ultrastructural features of the cell surfaces of uterine and trophoblastic epithelia during embryo attachment in the cow. Anat Rec. 1982;204:315–322. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092040404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin R.B. Amino acid requirements for attachment and outgrowth of the mouse blastocyst in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1966;68:335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Gwatkin R.B. Nutritional requirements for post-blastocyst development in the mouse. Amino acids and protein in the uterus during implantation. Int J Fertil. 1969;14:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao L.C., Tulac S., Lobo S., Imani B., Yang J.P., Germeyer A. Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2119–2138. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.H., Sarbassov D.D., Ali S.M., King J.E., Latek R.R., Erdjument-Bromage H. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y., Burghardt R.C., Wu G., Johnson G.A., Spencer T.E., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. VIII. Arginine stimulates proliferation of ovine trophectoderm cells through MTOR-RPS6K-RPS6 signaling cascade and synthesis of nitric oxide and polyamines. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:70–78. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.Y., Burghardt R.C., Wu G., Johnson G.A., Spencer T.E., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. VII. Effects of arginine, leucine, glutamine, and glucose on trophectoderm cell signaling, proliferation, and migration. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:62–69. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Burghardt R.C., Wu G., Johnson G.A., Spencer T.E., Bazer F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. IX. Differential effects of arginine, leucine, glutamine, and glucose on interferon tau, ornithine decarboxylase, and nitric oxide synthase in the ovine conceptus. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:1139–1147. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.088153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Erikson D.W., Burghardt R.C., Spencer T.E., Wu G., Bayless K.J. Secreted phosphoprotein 1 binds integrins to initiate multiple cell signaling pathways, including FRAP1/mTOR, to support attachment and force-generated migration of trophectoderm cells. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Song G., Gao H., Farmer J.L., Satterfield M.C., Burghardt R.C. Insulin-like growth factor II activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protooncogenic protein kinase 1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase cell signaling pathways, and stimulates migration of ovine trophectoderm cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3085–3094. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Song G., Wu G., Bazer F.W. Functional roles of fructose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. S. A. 2012;109:E1619–E1628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204298109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Song G., Wu G., Gao H., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W. Arginine, leucine, and glutamine stimulate proliferation of porcine trophectoderm cells through the MTOR-RPS6K-RPS6-EIF4EBP1 signal transduction pathway. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:113. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.105080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Choi Y., Bazer F.W., Spencer T.E. Identification of genes in the ovine endometrium regulated by interferon tau independent of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5203–5214. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball S.R., Shantz L.M., Horetsky R.L., Jefferson L.S. Leucine regulates translation of specific mRNAs in L6 myoblasts through mTOR-mediated changes in availability of eIF4E and phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11647–11652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H., Spencer T.E., Bazer F.W., Wu G. Developmental changes of amino acids in ovine fetal fluids. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:1813–1820. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.012971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacza Z., Snipes J.A., Zhang J., Horvath E.M., Figueroa J.P., Szabo C. Mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase is not eNOS, nNOS or iNOS. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:1217–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00510-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassala A., Bazer F.W., Cudd T.A., Datta S., Keisler D.H., Satterfield M.C. Parenteral administration of L-arginine prevents fetal growth restriction in undernourished ewes. J Nutr. 2010;140:1242–1248. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.125658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassala A., Bazer F.W., Cudd T.A., Datta S., Keisler D.H., Satterfield M.C. Parenteral administration of L-arginine enhances fetal survival and growth in sheep carrying multiple fetuses. J Nutr. 2011;141:849–855. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.138172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Bazer F.W., Gao H., Jobgen W., Johnson G.A., Li P. Amino acids and gaseous signaling. Amino Acids. 2009;37:65–78. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Rezaei R., Li P., Wu G. Composition of amino acids in feed ingredients for animal diets. Amino Acids. 2011;40:1159–1168. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0740-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipari C.W., Garcia J.E., Zhao Y., Thrift K., Vaidya D., Rodriguez A. Nitric oxide metabolite production in the human preimplantation embryo and successful blastocyst formation. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1316–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Chen L., Chung J., Huang S. Rapamycin inhibits F-actin reorganization and phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins. Oncogene. 2008;27:4998–5010. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther J.S., Windorski E.J., Schauer C.S. Impacts of L-arginine on ovarian function and reproductive performance in ewes. J Anim Sci. 2008;86(E-Suppl. 2):ii. [Google Scholar]

- Martin P.M., Sutherland A.E. Exogenous amino acids regulate trophectoderm differentiation in the mouse blastocyst through an mTOR-dependent pathway. Dev Biol. 2001;240:182–193. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P.M., Sutherland A.E., Van Winkle L.J. Amino acid transport regulates blastocyst implantation. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1101–1108. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.018010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo R.D., Wu G., Bazer F.W., Park J.C., Shinzato I., Kim S.W. Dietary L-arginine supplementation enhances the reproductive performance of gilts. J Nutr. 2007;137:652–656. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson B.A., Overstrom E.W., Albertini D.F. Transitions in trophectoderm cellular shape and cytoskeletal organization in the elongating pig blastocyst. Biol Reprod. 1990;42:195–205. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod42.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molderings G.J., Haenisch B. Agmatine (decarboxylated L-arginine): physiological role and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Ichisaka T., Maeda M., Oshiro N., Hara K., Edenhofer F. mTOR is essential for growth and proliferation in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6710–6718. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6710-6718.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen F.C., Ostergaard L., Nielsen J., Christiansen J. Growth-dependent translation of IGF-II mRNA by a rapamycin-sensitive pathway. Nature. 1995;377:358–362. doi: 10.1038/377358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platanias L.C. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin R., Casero R.A., Soulet D. Recent advances in the molecular biology of metazoan polyamine transport. Amino Acids. 2012;42:711–723. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0987-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaekers P., Kemp B., van der Lende T. Progenos in sows increases number of piglets born. J Anim Sci. 2006;84(Suppl. 1):394. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield M.C., Bazer F.W., Spencer T.E., Wu G. Sildenafil citrate treatment enhances amino acid availability in the conceptus and fetal growth in an ovine model of intrauterine growth restriction. J Nutr. 2010;140:251–258. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.114678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield M.C., Dunlap K.A., Keisler D.H., Bazer F.W., Wu G. Arginine nutrition and fetal brown adipose tissue development in diet-induced obese sheep. Amino Acids. 2012;43:1593–1603. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield M.C., Hayashi K., Song G., Black S.G., Bazer F.W., Spencer T.E. Progesterone regulates FGF10, MET, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 in the endometrium of the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:1226–1236. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.071787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S.F., Hua C.H. Effect of L-arginine on the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax in the placenta of fetal growth restriction. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:822–826. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.531315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slayden O.D., Keator C.S. Role of progesterone in nonhuman primate implantation. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:418–430. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W., Burghardt R.C. Implantation mechanisms: insights from the sheep. Reproduction. 2004;128:657–668. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T.E., Johnson G.A., Bazer F.W., Burghardt R.C. Fetal-maternal interactions during the establishment of pregnancy in ruminants. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2007;64:379–396. doi: 10.5661/rdr-vi-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B., O׳Dell D.K., Yu Y.W., Monn M.F., Hughes H.V., Burstein S. Identification of endogenous acyl amino acids based on a targeted lipidomics approach. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:112–119. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900198-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B., Yu Y.W., Monn M.F., Hughes H.V., O׳Dell D.K., Walker J.M. Targeted lipidomics approach for endogenous N-acyl amino acids in rat brain tissue. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:2890–2894. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranguch S., Steuerwald N., Huet-Hudson Y.M. Nitric oxide synthase production and nitric oxide regulation of preimplantation embryo development. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:1538–1544. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.009282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara Y., Minowa O., Mori C., Shiota K., Kuno J., Noda T. Placental defect and embryonic lethality in mice lacking hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Nature. 1995;373:702–705. doi: 10.1038/373702a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Burghardt R.C., Romero J.J., Hansen T.R., Wu G., Bazer F.W. Functional roles of arginine during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy. III. Arginine stimulates proliferation and interferon tau production by ovine trophectoderm cells via nitric oxide and polyamine-TSC2-MTOR signaling pathways. Biol Reprod. 2015;92:75. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.125989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Johnson G.A., Burghardt R.C., Wu G., Bazer F.W. Uterine histotroph and conceptus development. I. cooperative effects of arginine and secreted phosphoprotein 1 on proliferation of ovine trophectoderm cells via activation of the PDK1-Akt/PKB-TSC2-MTORC1 signaling cascade. Biol Reprod. 2015;92:51. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.125971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ying W., Dunlap K.A., Lin G., Satterfield M.C., Burghardt R.C. Arginine decarboxylase and agmatinase: an alternative pathway for de novo biosynthesis of polyamines for development of mammalian conceptuses. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:84. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.114637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Frank J.W., Little D.R., Dunlap K.A., Satterfield M.C., Burghardt R.C. Functional role of arginine during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy. I. Consequences of loss of function of arginine transporter SLC7A1 mRNA in ovine conceptus trophectoderm. FASEB J. 2014;28:2852–2863. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-248757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Frank J.W., Xu J., Dunlap K.A., Satterfield M.C., Burghardt R.C. Functional role of arginine during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy. II. Consequences of loss of function of nitric oxide synthase NOS3 mRNA in ovine conceptus trophectoderm. Biol Reprod. 2014;91:59. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.121202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel S.K., Dziuk P.J. Effect of stage of gestation and uterine space on prenatal survival in the pig. J Anim Sci. 1974;38:960–963. doi: 10.2527/jas1974.385960x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimsatt W.A. New histological observations on the placenta of the sheep. Am J Anat. 1950;87:391–457. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000870304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooding F.B. The role of the binucleate cell in ruminant placental structure. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1982;31:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. CRC Press; Boca Raton, Florida: 2013. Amino acids: biochemistry and nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. Functional amino acids in nutrition and health. Amino Acids. 2013;45:407–411. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1500-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F.W., Johnson G.A., Knabe D.A., Burghardt R.C., Spencer T.E. Triennial growth symposium: important roles for L-glutamine in swine nutrition and production. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:2017–2030. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F.W., Burghardt R.C., Johnson G.A., Kim S.W., Knabe D.A. Proline and hydroxyproline metabolism: implications for animal and human nutrition. Amino Acids. 2011;40:1053–1063. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0715-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F.W., Burghardt R.C., Johnson G.A., Kim S.W., Li X.L. Impacts of amino acid nutrition on pregnancy outcome in pigs: mechanisms and implications for swine production. J Anim Sci. 2010;88:E195–E204. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F.W., Davis T.A., Kim S.W., Li P., Marc Rhoads J. Arginine metabolism and nutrition in growth, health and disease. Amino Acids. 2009;37:153–168. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0210-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F.W., Johnson G.A., Burghardt R.C., Li X., Dai Z. Maternal and fetal amino acid metabolism in gestating sows. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2013;68:185–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Wu Z., Dai Z., Yang Y., Wang W., Liu C. Dietary requirements of ”nutritionally non-essential amino acids” by animals and humans. Amino Acids. 2013;44:1107–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Bazer F.W., Wallace J.M., Spencer T.E. Board-invited review: intrauterine growth retardation: implications for the animal sciences. J Anim Sci. 2006;84:2316–2337. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Imhoff-Kunsch B., Girard A.W. Biological mechanisms for nutritional regulation of maternal health and fetal development. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(Suppl. 1):4–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2012.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Meininger C.J. Nitric oxide and vascular insulin resistance. Biofactors. 2009;35:21–27. doi: 10.1002/biof.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G., Morris S.M., Jr. Arginine metabolism: nitric oxide and beyond. Biochem J. 1998;336(Pt 1):1–17. doi: 10.1042/bj3360001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M.N. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X.M., Li L.P. L-Arginine treatment for asymmetric fetal growth restriction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88:15–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Huang Z., Mao X., Wang J., Wu G., Qiao S. N-carbamylglutamate enhances pregnancy outcome in rats through activation of the PI3K/PKB/mTOR signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Mao X., Huang Z., Wang F., Wu G., Qiao S. Arginine enhances embryo implantation in rats through PI3K/PKB/mTOR/NO signaling pathway during early pregnancy. Reproduction. 2013;145:1–7. doi: 10.1530/REP-12-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Wang F., Fan X., Yang W., Zhou B., Li P. Dietary arginine supplementation during early pregnancy enhances embryonic survival in rats. J Nutr. 2008;138:1421–1425. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.8.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]