Abstract

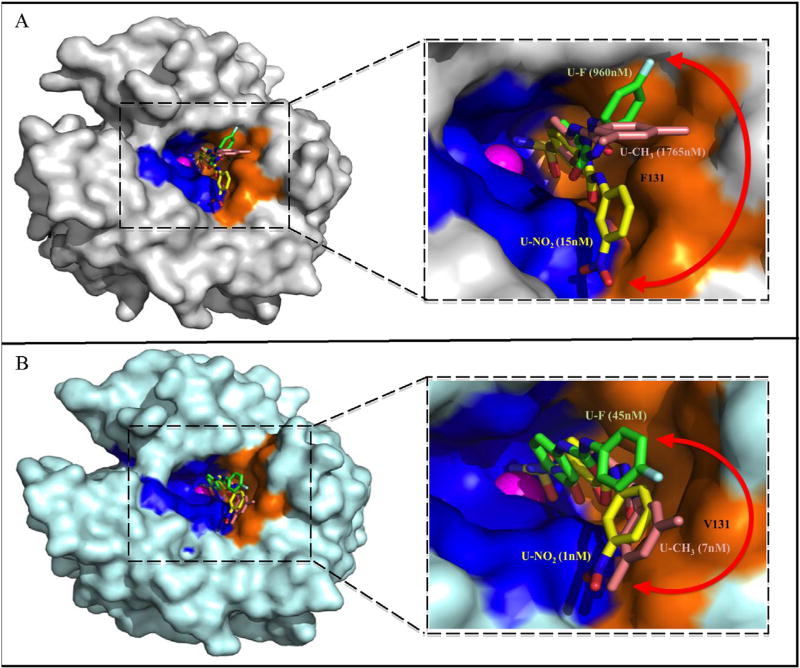

Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides (USBs) show great promise as selective and potent inhibitors for human carbonic anhydrase hCA IX and XII, with one such compound (SLC-0111/U-F) currently in clinical trials (clinical trials.gov, NCT02215850). In this study, the crystal structures of both hCA II (off-target) and an hCA IX-mimic (target) in complex with selected USBs (U-CH3, U-F, and U-NO2), at resolutions of 1.9 Å or better, are presented, and demonstrate differences in the binding modes within the two isoforms. The presence of residue Phe 131 in hCA II causes steric hindrance (U-CH3, 1765 nM; U-F, 960 nM; U-NO2, 15 nM) whereas in hCA IX (U-CH3, 7 nM; U-F, 45 nM; U-NO2, 1 nM) and hCA XII (U-CH3, 6 nM; U-F, 4 nM; U-NO2, 6 nM), 131 is a Val and Ala, respectively, allows for more favorable binding. Our results provide insight into the mechanism of USB selective inhibition and useful information for structural design and drug development, including synthesis of hybrid USB compounds with improved physiochemical properties.

Keywords: Benzenesulfonamides, Carbonic anhydrase IX, hCA IX-Mimic, Structure-activity relationships, X-ray crystallography, Cancer therapy

1. Introduction

A commonly observed feature of solid tumors is regions comprised of proliferating and highly metabolic cells. These cells typically display a hypoxic phenotype, which leads to increased acidity in the tumor microenvironment and a metabolic shift that favors a progression to metastasis [1]. This hypoxic phenotype results when tumor cells outgrow their blood supply leading to low oxygen levels, and in response, undergo oncogenic alternations in their metabolism to over express proteins essential for survival [1,2]. Human Carbonic Anhydrase (hCA IX; EC 4.2.2.1) is one such protein, which is mainly induced by hypoxia and functions as a pH regulatory factor [3]. The expression of hCA IX has been shown to be crucial for tumor cell survival and proliferation due to its ability to normalize the intracellular pH (pHi), while maintaining low extracellular pH (pHe) [4]. This extracellular acidification of the tumor microenvironment promotes local invasion and metastasis, while decreasing the effectiveness of adjuvant therapies. These features contribute to poor clinical outcomes in cancer patients [5]. Although hCA XII expression is not modulated by hypoxia, it is also shown to be upregulated in many aggressive tumors and, similar to hCA IX, it functions to regulate both intra and extracellular pH.

Like other α-CAs, hCA IX and hCA XII belong to a family of zinc metalloenzymes that catalyze the reversible hydration of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate and a proton via a ping-pong mechanism, a key reaction for pH regulatory mechanisms [6]. In contrast to other hCA isoforms, hCA IX expression in normal cells is limited to the stomach and gastrointestinal tract. However, it is upregulated in many solid and aggressive tumors including the brain, breast, bladder, cervix, colon, colorectal, head and neck, pancreas, kidney, lung, ovaries, stomach and oral cavity [7]. Its overexpression in cancer is linked to hypoxia, extracellular acidification, chemotherapeutic resistance, poor prognosis and clinical outcome [4,8]. Conversely, hCA XII is expressed in many normal tissues including pancreas, colon and breast. Because the expression of hCA IX is increased in hypoxic tumors and plays a role in tumor progression, acidification, and metastases, it already serves as a target for imaging and predicting therapeutic outcome [4,9]. hCA XII may also serve as a therapeutic target because of its elevated regulation in cancer. Further, the extracellular location and hCA IX's limited expression in normal tissues, makes both isozymes favorable for drug targeting and delivery in aggressive cancer treatment [7,10]. Indeed, inhibition of hCA IX and hCA XII activity in tumor cells has been shown to reduce tumor growth and proliferation, thus establishing hCA IX and potentially hCA XII as anti-cancer drug targets [9,11].

Several classes of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have been developed and are used clinically for treatment of diseases [9,12]. However, most of these inhibitors are not hCA IX and hCA XII specific which will reduce their efficacy or produce off-target side effects when used as anti-cancer agents due to inhibition of other carbonic anhydrases (particularly that of the ubiquitously expressed cytosolic hCA II) [9,13]. Difficulties in designing and developing hCA IX/hCA XII-specific inhibitors stem from the fact that the 15 human CA isoforms are all structurally homologous with many conserved residues residing within the active site [14]. To this extent, a structure-based drug design approach has shown to be useful for the development of isoform selective hCA IX and hCA XII inhibitors. Specifically, using compounds that contain a zinc-binding group (ZBG) coupled to a variable chemical moiety, known as the compound “tail” can facilitate specific interactions with specific residues within the active site. This is the predominant method for developing selective hCA IX inhibitors – a method known as the “tail approach” [14].

Recently, ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides (USBs) have been shown to selectively inhibit hCA IX and XII [11]. This class of inhibitors also showed both anti-proliferative and anti-metastatic activity in mouse models of breast cancer [11]. One of these USBs, name SLC-0111, is in Phase 1 clinical trials (see, clinical trials.gov, NCT02215850) for the treatment of solid tumors over expressing hCA IX and XII (Table 1) [11,15]. Despite the success of these compounds, the structure-activity relationships (SARs) of these inhibitors have not been extensively studied, a necessity towards improving USBs for “next generation” hCA IX and XII inhibitors.

Table 1.

Inhibitions for hCA isoforms with ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamide compound SLC-0111/U-F.

| Isoform | Ki (nM)a |

|---|---|

| hCA I | 5080 |

| hCA II | 960 |

| hCA III | 7918 |

| hCA IV | 286 |

| hCA VA | 2545 |

| hCA VB | 908 |

| hCA VI | 6490 |

| hCA VII | 8550 |

| hCA IX | 45 |

| hCA XII | 4 |

| hCA XIII | 8755 |

| hCA XIV | 257 |

Here, we provide insights into the SARs of USBs in hCA IX compared to hCA II and identify important interactions between these compounds and hCA IX and XII, which provides the mechanism(s) for their selective inhibition. Further, we utilize this information to suggest ways to improve this class of compounds to increase both selectivity and potency towards hCA IX and XII. These include addition of an NO2 group to improve hCA IX specificity and/or addition of F/CH3 groups to improve specificity, solubility and physiochemical properties. We utilize three USB derivatives with varying chemical properties denoted, U-CH3, U-NO2, and U-F (SLC-0111) (Fig. 1) and determined their X-ray crystallography structures in complex with hCA II and the hCA IX-mimic (hCA II with active site substitutions Ala65Ser, Asn67Gln, Glu69Thr, Ile91Leu, Phe131Val, Lys170Glu, and Leu204Ala to closely resemble the active site of hCA IX; hCA II numbering) [16]. Information from these studies provide a foundation for SARs between clinically used USBs and hCA IX and will be of value in the design of next generation inhibitors for the treatment of aggressive cancers.

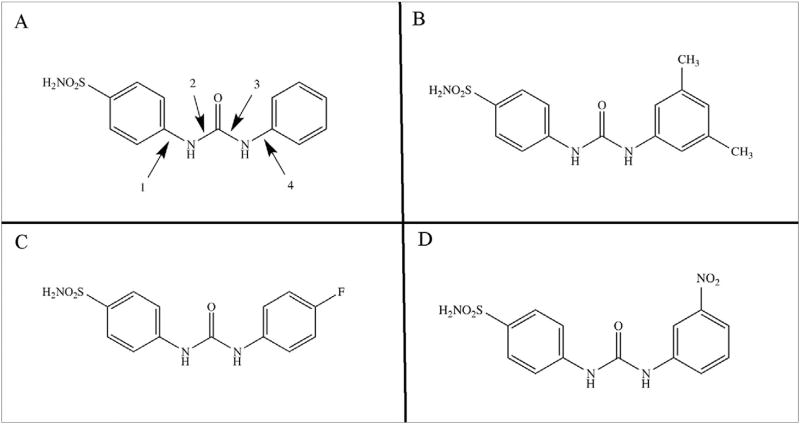

Fig. 1.

Structures of ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamide inhibitors. The general construct shows the primary sulfamate ZBG is conjugated to benzene incorporating 4-substituted ureido moieties A) and an R moiety present in the ureido tail of the compound (B–D). Numbers 1, 2, 3 and 4 refer to torsion angles in Table 3.

2. Results

2.1. Selective hCA IX and XII inhibition

A series of USBs have been designed and synthesized previously by Pacchiano et al. [11,17] The rationale for their design was influenced by the observations of hCA isoform specific inhibition and the dependence on the substitution pattern of the urea moiety. The general structure includes a primary sulfonamide ZBG conjugated to benzene, which incorporates a 4-substituted ureido moiety and an R group(s) present in the tail region (Fig. 1, Supplemental Fig. S1) [11]. The 3 inhibitors investigated here were U-CH3 (4-{[3,5-methylphenyl)carbamoylamino} benzenesulfonamide) where R is two methyl groups (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Figs. S1A and S1B), U-F (4-{[4-fluorophenyl)carbamoyl]amino}benzenesulfonamide) where R is 4-fluorophenyl (Fig. 1C, Supplemental Figs. S2C and S2D), and U-NO2 (4-{[3-nitrophenyl) carbamoyl] amino}benzenesulfonamide where R is 3-nitrophenyl (Fig. 1D, Supplemental Fig. S1E) [11c]. All three USBs showed selective inhibition of hCA IX and XII over hCA II and displayed variable selectivity ratios with dependency on the substituted R group (Table 2). U-NO2 is the most potent hCA IX inhibitor with a Ki of 1 nM and also a good inhibitor of hCA XII with a Ki of 6 nM, but also the least selective against hCA II with II/IX and II/XII ratios of 15 and 2, respectively. U-CH3 is also a potent inhibitor of hCA IX and XII, with Ki's of 7 and 6 nM, respectively and displayed the least specificity for hCA II with a Ki value of 1765 nM and showed similar selectivity ratios of 250 and 300 for hCA IX and hCA XII, suggesting that the increased hydrophobicity (with the CH3 substituents) provides specificity for tumor-associated isozymes over the ubiquitously expressed hCA II. U-F showed ~2-fold higher specificity compared to U-CH3 for hCA XII (Ki = 4 nM) and good affinity for hCA IX (Ki = 45 nM) compared to hCA II (Ki = 960 nM), the selectively ratios are 240 and 20 fold for hCA IX and hCA XII, respectively. Based on the ability of U-F and U-NO2 to selectively bind to hCA IX (and XII) over hCA II, these inhibitors were further studied in vivo using mouse models of metastatic breast cancer that overexpress hCA IX [11]. The inhibitors were shown to suppress tumor growth in a concentration-dependent manner and effectively attenuate formation of metastasis in vivo. The authors for this study indicated that administration of the compounds did not result in significant weight loss, suggesting that the inhibitors were not generally toxic [11]. These observations may be attributable to the observed increased isoform selectivity by these inhibitors as shown by CA inhibition studies performed using applied photophysics stopped-flow technology (Tables 1 and 2) [11,17].

Table 2.

Inhibition and isozyme selectivity ratio for hCA II, IX, and XII with ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamide compounds U-CH3, U-F, and U-NO2.

| Compound |

Ki (nM)a

|

Selectivity Ratiob

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hCA II | hCA IX | hCA XII | II/IX | II/XII | IX/XII | XII/IX | |

| U-CH3 | 1765 | 7 | 6 | 250 | 300 | 1 | 1 |

| U-F | 960 | 45 | 4 | 20 | 240 | 10 | <1 |

| U-NO2 | 15 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 2 | <1 | 5 |

Ki values obtained from Pacchiano et al., [11]: U-CH3 (3,5-Me2C6H3), U-F (4-FC6H4), U-NO2 (3-O2NC6H4).

Selectivity as determined by the ratio of Kis for hCA isozyme relative to hCA IX and hCA XII.

2.2. X-ray crystallographic results

Structures of the three ureidosulfonamide compounds (U-CH3, U-F and U-NO2) in complex with both hCA II and the hCA IX-mimic were determined using X-ray crystallography to resolutions of 1.9 Å or better (statistics summarized in Table 3). Unambiguous omit (Fo-Fc) electron density maps were apparent for all compounds within the active site of both hCA II and the hCA IX-mimic, and showed a ≥90% occupancy in the final refined structures (Supplemental Fig. S1). As commonly observed with sulfonamide-based hCA inhibitors, the compounds were shown to block hCA catalysis through binding directly to the catalytic zinc of both hCAs displacing the zinc-bound OH−/H2O via the primary sulfonamide group [18]. For all compounds the benzene (C1–5) sulfonamide core are within Van der Waals distances from the conserved side chains of Leu 198, Val 121, Val 143 and Thr 200 (Figs. 2 and 3). Additional electron density consistent with a bound glycerol molecule, from the cryoprotectant solution used during data collection, was observed adjacent to the aromatic ring of the benzene sulfonamide in the active site of hCA II but not hCA IX-mimic (data not shown) [19].

Table 3.

X-ray crystallography statistics of USBs bound hCA IX-mimic and hCA II structures.

| Sample PDB ID | hCA IX-mimic: U- CH3 5JN1 |

hCA IX-mimic: U-F 5JN3 |

hCA IX-mimic: U- NO2 5JMZ |

hCA II: U-CH3 5JN7 |

hCA II: U-F 3N4D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space Group Cell Dimensions (Å;°) | P21 a = 42 ± 0.8, b = 42 ± 0.8, c = 72 ± 0.5; β = 104 ± 0.3 | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 29.1–1.51 (1.53–1.51) | 19.9–1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 19.9–1.90 (2.00–1.90) | 29.1–1.52 (1.55–1.52) | 20.0–1.55 (1.58–1.55) |

| Total Reflections | 65546 | 53075 | 61159 | 55980 | 63099 |

| Rsyma (%) | 5.8 (34.7) | 6.0 (50.0) | 5.8 (19.8) | 6.9 (48.9) | 7.8 (27.2) |

| I/Iσ | 31.0 (3.7) | 29.5 (3.1) | 19.4 (6.3) | 28.6 (3.2) | 25.5 (5.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) | 100.0 (100.0) | 96.6 (96.7) | 96.4 (97.3) | 98.2 (98.7) |

| Rcrystb (%) | 16.1 (20.4) | 16.9 (22.8) | 16.7 (18.2) | 16.5 (24.5) | 16.1 (16.9) |

| Rfreec (%) | 18.4 (20.0) | 19.6 (20.2) | 19.9 (23.8) | 18.9 (33.0) | 18.8 (20.0) |

| # of Protein Atoms | 2048 | 2123 | 2046 | 2053 | 2093 |

| # of Water Molecules | 185 | 187 | 170 | 208 | 205 |

| # of Ligand Atoms | 22 | 21 | 23 | 22 | 21 |

| Ramachandran stats (%): Favored, allowed, outliers | 96.1, 4.0, 0.0 | 96.8, 3.2, 0.0 | 97.2, 2.8, 0.0 | 96.8, 3.2, 0.0 | 96.8, 3.2, 0.0 |

| Avg. B factors (Å2): Main-chain, Side-chain, Solvent, Ligandd | 14.2, 19.0, 26.3, 13.4 | 15.3, 19.6, 23.5, 23.7 | 18.6, 23.3, 28.7, 37.9 | 14.8, 19.3, 25.6, 27.7 | 13.8, 17.9, 23.3, 23.1 |

Rsym = (Σ|I - <I>|/Σ <I>) × 100.

Rcryst = (Σ|Fo - Fc|/Σ |Fo|) × 100.

Rfree is calculated in the same way as Rcryst except it is for data omitted from refinement (5% of reflections for all data sets).

Values in parenthesis correspond to the highest resolution shell.

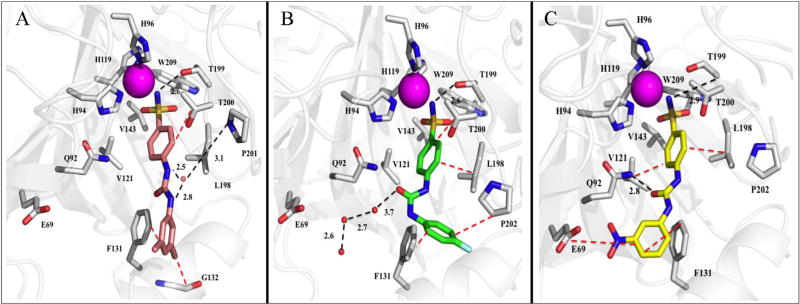

Fig. 2.

Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides bound in the active site of hCA II (grey). A) Compound U-CH3 (pink) B) Compound U-F (green) and C) Compound U-NO2 (yellow) with active site residues and relative bond distances (Å) labeled. Specific interactions of compounds with the active site of hCA II are indicated as black dotted lines and hydrophobic interactions shown as red dotted lines. The zinc (magenta) and solvent (red) are represented as spheres. The figure was made using PyMol.26. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

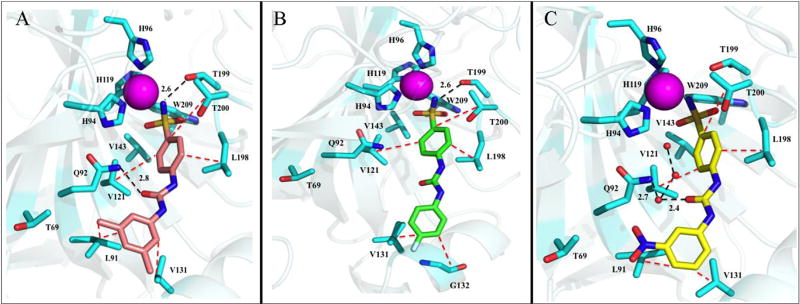

Fig. 3.

Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides bound in the active site of hCA IX-mimic (cyan). A) Compound U-CH3 (pink) B) Compound U-F (green) and C) Compound U-NO2 (yellow) with active site residues and relative bond distances (Å) labeled. Specific interactions of compounds with the active site of hCA II are indicated as black dotted lines and hydrophobic interactions shown as red dotted lines. The zinc (magenta) and solvent (red) are represented as spheres. The figure was made using PyMol.26. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2.1. Compound U-CH3

A structural comparison of the binding of U-CH3 within the active sites of hCA II and IX (mimic) demonstrated distinct differences which most likely contribute to the ~250-fold selectivity of binding for hCA IX over hCA II (Table 2, Figs. 2A and 3A). Contributing to this conformational change in U-CH3 is residue Phe 131 in hCA II, which reduces the accessible opening of the active site and acts as a binding anchor to the tail (Fig. 2A). In hCA IX, this residue is Val 131 which opens the active site cavity (Fig. 3A). Having fewer constraints on the conformational torsion angles in hCA IX allows the tail of U-CH3 to rotate (Table 4) and release a trapped solvent molecule in a hydrophobic pocket (near Leu 198 when bound in hCA II). This ~90° rotation also permits the oxygen of the ureido group to H-bond with the nitrogen of Gln 92 (2.8 Å), and Leu 91 and Val 131 to form specific hydrophobic interactions with the CH3 substituted R groups (Fig. 3A). These observations, taken together, explain the increase of interactions for U-CH3 bound in hCA IX compared to hCA II, measured using PDBePISA [20], and therefore the ~250-fold selectivity of binding for hCA IX over hCA II (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1).

Table 4.

Torsion angles (°) of the USB compounds U-CH3, U-F, and U-NO2 bound to the active sites of hCA II and hCA IX-mimic, respectively. Definition for torsion angles given in Fig. 1.

| Angle | hCA II: U-CH3 | hCA IX-mimic: U-CH3 | hCA II: U-F | hCA IX-mimic: U-F | hCA II: U-NO2 | hCA IX-mimic: U-NO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | −38 | −45 | 5 | −34 | −36 |

| 2 | 178 | −177 | 179 | 176 | −179 | 180 |

| 3 | 178 | 176 | −1 | 177 | −176 | 179 |

| 4 | 54 | −33 | 151 | −56 | −19 | −33 |

2.2.2. Compound U-F

The change in conformational rotamers for U-F binding between hCA IX over hCA II were larger than for U-CH3, with the fluorophenyl moiety rotated more than 100° towards Pro 202 in hCA II (because of the jutting Phe 131) (Table 4). Compound U-F therefore becomes sandwiched between the two groups in hCA II, whereas in hCA IX the tail sits in the hydrophobic pocket created by Val 131 and Gly 132 (Fig. 3A and B). The binding of U-F to hCA II does not result in the displacement of all the active site waters some of which are shown to participate in hydrogen bonding. Lack of solvent displacement most likely contributes to the lower Ki for U-F binding to hCA II compared to U-CH3 and also reduces its selectivity for hCA IX (Table 2, Figs. 2B and 3B).

2.2.3. Compound U-NO2

The crystal structures clearly show why compound U-NO2 is a good inhibitor for both hCA II and IX, as the compound shows little conformational change in either active site (Table 4). Residues Val 121, Val 143, and Leu 198, interact with the core benzene (Figs. 2C and 3C). Additional hydrophobic interactions are also observed between Phe 131 and Leu 91 and Val 131 and the nitrophenyl ring of U-NO2 in hCA II and IX, respectively (Figs. 2C and 3C). In addition, the presence of Phe 131 in hCA II does not distort the tail conformation, which allows U-NO2 to directly H-bond with Gln in hCA II, by a bridging water molecule in hCA IX. It should be noted that the binding of U-NO2 within the active site of hCA II has been previously reported [11c,17]. But, the present comparison with hCA IX now demonstrates why the Ki's are similar and why there is little to no isoform selectivity between hCA II and IX (Table 2).

3. Discussion

3.1. Structure activity relationships of the hCA active site

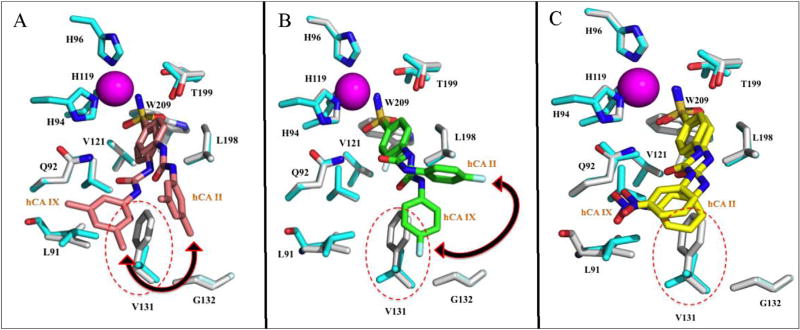

The ureido linker present between the sulfamoylphenyl fragment and the R moiety of the ureidosulfonamide inhibitors allow for rotatable R tails (Table 4). This permits the compounds to adopt a range of conformations and participate in diverse interactions within the enzyme active site, with no significant conformal changes observed for the active site side chains, other than the removal of the bulky hydrophobic residue Phe 131 (Figs. 4 and 5). For instance, U-CH3, which has a Ki for hCA II of 1765 nM and a significantly lower Ki for hCA IX of 7 nM, adopts a significantly different conformation upon binding the hCAs, which is most likely due to Phe 131 in hCA II (Fig. 4A and Table 4). Superposition of the structures of hCA IX-mimic and hCA II in complex with U-CH3 clearly shows Phe 131 in hCA II would cause steric hindrance if it bound in the same conformer in hCA IX, hence the conformational changes in both compound U-CH3 and U-F and the interactions that can be formed (Fig. 4). The structure of hCA II bound to U-CH3 (average B factor of 27.7 Å2) showed weak interactions and stabilization of the tail moiety by Phe 131 and Gly 132, instead of Leu 91 and Val 131 as seen in the crystal structure of hCA IX-mimic bound U-F (average B factor of 13.4 Å2) (Figs. 2A and 3A). The difference in average B factors between bound compound UF in the active site of hCA II and hCA IX-mimic is therefore a good indicator of the conformer stability of the compound specific to each isoform. To this extent it is assumed that different favorable/unfavorable contacts between the inhibitor tail moiety and the enzyme active site lead to different inhibition profiles for this class of sulfonamides. This phenomenon was also observed in the superimposed structures of U-F bound hCA II and hCA IX-mimic in which a ~90° shift of the fluorophenyl tail moiety in the active site of hCA II occurred (Fig. 4B). The conformational change also caused differences in hCA II residues interacting and possibly further stabilizing the tail moiety of U-F. The observed interacting hCA II residues are Phe 131 and Pro 202 and for hCA IX-mimic, which has a lower Ki value (hCA IX-mimic = 45 nM and hCA II = 960 nM), are Val 131 and Gly 132 (Figs. 2B and 3B). In the superimposed structures of U-NO2 bound hCA II and hCAIX-mimic, little to no conformational change of the inhibitor was detected (Fig. 4C). This observation correlates to the reduced isoform selectivity of this compound when compared to U-CH3 and U-F. In summary, our results suggest a close correlation between the previously determined kinetic and our X-ray crystallographic data with the selectivity profiles of benzenesulfonamides incorporating ureido tails. The flexibility of the ureido linker allows for variable conformations of the tail to be adapted providing acceptable isoform specificity and selectivity for these compounds, which are desirable for a drug candidate. It is also clear from this and previous studies that designing isoform selective hCA IX inhibitors requires the exploitation of residues in the CA selective pocket (15 Å away from the active site zinc), which confer the desired hCA IX and hCA XII specificity (Table 5) [14,21]. It is predicted that the reason for the preferred inhibitor interactions with the hydrophobic and not the hydrophilic pocket is the absence of bulky residues in the hCA IX and hCA XII active sites such as Phe 131 that reduce steric hindrance of the compound (Table 5) [14,21]. In hCA IX, residue 131 is a Val and hCA XII has an Ala at that site (Table 5). Although both residues are relatively small with short hydrophobic side chains, Ala is also considered nucleophilic. These small residues allow the compounds to freely enter the active site in a conformation that favors interactions with residues in the hydrophobic pocket to induce selectivity. The residue differences between hCA IX and hCA XII, but especially at site 131, may also confer specificity for one membrane bound isoform over the other. These observations, when taken together, provide necessary parameters for designing potent hCA IX and hCA XII specific and selective inhibitors for the treatment of cancer.

Fig. 4.

Overlay of compounds A) U-CH3 (pink), B) U-F (green) and C) U-NO2 bound to the active site of hCA II (grey) onto inhibitor bound hCA IX-mimic (cyan) with specific residues labeled. Active site zinc shown as magenta sphere, red dotted circles indicate residues within the active site of hCA IX-mimic that differ from hCA II. Black double-headed arrow indicates the direction of conformational change of the compounds bound to hCA IX-mimic in comparison to hCA II. The figure was made using PyMol.26. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 5.

Surface representation of ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamide compounds bound to the active site of A) hCA II (grey) and B) hCA IX-mimic (cyan). Compound U-CH3 (pink), c U-F (green), and U-NO2 (yellow). Zinc (magenta sphere), hydrophilic (blue) and hydrophobic (orange) residues are as shown. Red double-headed arrows indicate isoform specificity relative to residue 131 (labeled in black). The Ki values of each compound bound to hCA II and hCA IX are also labeled. The figure was made using PyMol.26. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 5.

Resides within the active site of hCA II, hCA IX and hCA XII that differ and make up the selective pocket (hCA II numbering).

| Residues | hCA II | hCA IX | hCA XII |

|---|---|---|---|

| 67 | Asn | Gln | Lys |

| 91 | Ile | Leu | Thr |

| 131 | Phe | Val | Ala |

| 135 | Val | Leu | Ser |

Information adapted from Pinard et al. [14].

4. Conclusions

Its limited expression in normal tissue, its extracellular catalytic domain, its upregulation in many aggressive tumors, and a therapeutically favorable response when inhibited, rationalize targeting hCA IX for cancer treatment [7,22]. Specifically, inhibition of the catalytic activity of hCA IX has been shown to decrease tumor growth, prevent metastases and increase overall survival rates [4,8]. Thus, targeting hCA IX activity in tumors that overexpress this enzyme provides a useful approach for treatment of several aggressive cancers. Here, we present novel structural information on a series of ureido-substituted benzene sulfonamide based (USB) inhibitors previously determined as selective inhibitors of hCA IX and hCA XII over off-target hCA II and I [11]. Our findings identify key interacting residues and pinpoint the advantage of using compounds with flexible linker regions. We have shown in this study how ureido sulfonamide based inhibitors may provide an avenue to overcome CA isoform specificity, as they display both nanomolar affinity and preferential binding for the tumor associated membrane bound isoforms. For instance, U-CH3, which is the most selective of the three inhibitors, exhibits greater than a 200-fold increase in selectivity for hCA IX and hCA XII over hCA II. Compound U-NO2 is the most potent inhibitor of hCA IX, but it is also the least isozyme selective. U-F displays increased potency for hCA XII. The crystal structures of U-CH3, U-F and U-NO2 bound to the active site of hCA IX in comparison to hCA II show that residue 131 may play a critical role in determining compound selectivity. As previously mentioned, the difference in residues at position 131 in the active site of hCA IX (Val 131) and hCA II (Phe 131) cause conformational changes in the inhibitors. These changes dictate the types of interactions that can be formed to stabilize the inhibitors within the active site of hCAs. Furthermore, the introduction of strong electron-withdrawing groups (3-NO2 and 4-F) or highly electron-donating (3,5-dimethyl) causes a polarization within the entire molecule and extended conjugation system. This also means better solubility of these compounds in aqueous solution.

In designing the next generation of hCA IX and hCA XII inhibitors that incorporate substituted benzene sulfonamide moieties, it is important that the chemical properties of these inhibitors also be considered. For instance, compound U-NO2 is the most potent hCA IX inhibitor but it is also the least soluble among the three inhibitors. To improve its solubility/selective properties, a hybrid compound could be synthesized, in which either one or multiple F and/or CH3 group(s) are incorporated into the terminal benzene ring, with improved Van der Waal contacts. This may increase its hydrophilicity and perhaps isoform selectivity. Another approach might be the addition of an NO2 at position C1/C2/C3 of the substituted benzene moiety in U-CH3 or U-F compounds. These substitutions or others may aid in the development of more potent hCA IX and hCA XII specific and selective inhibitors with improved physiochemical properties. In summary, these studies provide new insight into USB selective CA inhibition and for the first time “map” key residue interactions of the hCA IX active site in complex with USBs [21]. This information will provide important parameters needed to design and develop antiproliferative and antimetastatic drugs that target hCA IX.

5. Experimental section

5.1. Protein expression, purification and CA IX-mimic design [23]

HCA II and hCA IX-mimic cDNA were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells in Luria broth medium containing ~0.1 mg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C to an optical density of ~0.6 at 600 nm. Protein expression was induced using 0.1 mg/ml isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactoside (IPTG) and 1 mM zinc sulphate. The cells were incubated for an additional 3 h and harvested by centrifugation. Purification was performed using affinity chromatography, proteins were eluted (400 mM sodium azide, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.8), buffer exchanged (into 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8) and then concentrated via centrifugal ultra-filtration using a 10 kDa MWCO filter. Protein purity was checked by SDS-PAGE (stained with coomassie blue) and concentration determined by UV/Vis spectroscopy, and measured to be 29 and 20 mg/ml for hCA II and IX-mimic, respectively. The concept of the engineered hCA IX-mimic was conceived by Genis et al., and developed further by Pinard et al., and constructed by site-directed mutagenesis of the active site of hCA II [23]. The substituted residues in the hCA IX-mimic are analogous to wild type hCA IX, generating an extremely stable construct that readily crystallizes [10,16,23]. Active site mutations in the hCA IX-mimic include; Ala65Ser, Asn67Gln, Glu69Thr, Ile91Leu, Phe131Val, Lys170Glu, and Leu204Ala.

5.2. X-ray crystallography

Crystals of purified hCA II and hCA IX-mimic were obtained using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method, with 1.6 M Na-Citrate, 50 mM Tris, and pH 7.8 as the precipitant solution and incubated at room temperature. Crystals formed after 5 days [10,16,23]. 10 mM stock concentrations of each inhibitor (provided by Dr. Claudiu T. Supuran) were prepared in a 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution. Prior to being added to the crystal drop, stock solutions were diluted in a mixture 1:1 deionized water and precipitant solution to the desired compound concentrations of ~10 µM. Crystals were then equilibrated with the precipitant-inhibitor solution 48 h prior to data collection. Diffraction data was collected either “in-house” using an RU-H3R rotating Cu anode (λ = 1.5418 Å) operating at 50 kV and 22 mA utilizing a 0.3 mm R-Axis VI++ image plate detector (Rigaku, USA) or on the F1 beamline (λ = 0.9177 Å) at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS). Data sets were integrated, merged and scaled using the HKL2000 software package, all to a P21 space group [24]. Initial phases were calculated using molecular replacement using PDB entry 3KS3 [18] (hCA II) with waters and ligands removed, as a search model. Initial phase determination, model refinements, and generation of ligand restraint files were performed using PHENIX suite of programs [25]. Models for ligand-protein complexes were generated using Coot and LigPlus [26]. Coot was also used to determine bond lengths and angles used for analysis as well as PDB files for ligands [26,27]. Figures were generated using PyMol [26]. Diffraction data and final model statistics are summarized in Table 2.

5.3. Ligand binding studies

The buried and accessible surfaces areas of all compounds in their respective crystal structures were calculated using the online Proteins, Interfaces, Surfaces and Assemblies algorithm provided by the Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBePISA) [20]. The ΔG values indicate the solvation free energy gain upon formation of the interface but not the effect of satisfied hydrogen bonds and salt bridges across the interface. ASA and BSA indicate the accessible surface and buried surface areas of the proteins upon inhibitor binding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the staff at Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) for assisting with data collection. We would also like to thank Zhijuan Chen, Justin Kurian and Melissa Pinard for their valuable input and support.

Funding sources

This research was financed by the National Institutes of Health, project CA165284 (SCF) and minority supplement CA165284-03S1 (MYM).

Footnotes

Accession codes

Coordinates and structure factors for all structures have been deposited to the PDB with the following accession codes: 5JN1, 5JN3, 5JMZ, 5JN7 and 3N4D.

Author contributions

M.Y.M. wrote the paper, performed and analyzed the experiments. B.P.M., N.L., and L.S. performed and analyzed the experiments. F.C., and C.T.S. designed and synthesized the compounds. S.C.F., and R.M. designed the study and reviewed the paper. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.026.

References

- 1.(a) DeBerardinis RJ. Is cancer a disease of abnormal cellular metabolism? New angles on an old idea. Genet. Med. 2008;10:767–777. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818b0d9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deberardinis RJ, Sayed N, Ditsworth D, Thompson CB. Brick by brick: metabolism and tumor cell growth. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2008;18:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Verduzco D, Lloyd M, Xu L, Ibrahim-Hashim A, Balagurunathan Y, Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Intermittent hypoxia selects for genotypes and phenotypes that increase survival, invasion, and therapy resistance. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Hockel M, Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sadri N, Zhang PJ. Hypoxia-inducible factors: mediators of cancer progression; prognostic and therapeutic targets in soft tissue sarcomas. Cancers (Basel) 2013;5:320–333. doi: 10.3390/cancers5020320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Warburg O, Geissler AW, Lorenz S. On growth of cancer cells in media in which glucose is replaced by galactose. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol. Chem. 1967;348:1686–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Racker E. Warburg effect revisited. Science. 1981;213:1313. doi: 10.1126/science.6765631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Wykoff CC, Beasley NJ, Watson PH, Turner KJ, Pastorek J, Sibtain A, Wilson GD, Turley H, Talks KL, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Harris AL. Hypoxia-inducible expression of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7075–7083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ. Identification of novel hypoxia dependent and independent target genes of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumour suppressor by mRNA differential expression profiling. Oncogene. 2000;19:6297–6305. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) McDonald PC, Winum JY, Supuran CT, Dedhar S. Recent developments in targeting carbonic anhydrase IX for cancer therapeutics. Oncotarget. 2012;3:84–97. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chiche J, Ilc K, Laferriere J, Trottier E, Dayan F, Mazure NM, Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia-inducible carbonic anhydrase IX and XII promote tumor cell growth by counteracting ccidosis through the regulation of the intracellular pH. Cancer Res. 2009;69:358–368. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiche J, Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouyssegur J. Tumour hypoxia induces a metabolic shift causing acidosis: a common feature in cancer. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2010;14:771–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Silverman DN, Lindskog S. The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase - implication of a rate limiting protolysis of water. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988;21:30–36. [Google Scholar]; (b) Supuran CT. Structure and function of carbonic anhydrases. Biochem. J. 2016;473:2023–2032. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Leibovich BC, Sheinin Y, Lohse CM, Thompson RH, Cheville JC, Zavada J, Kwon ED. Carbonic anhydrase IX is not an independent predictor of outcome for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:4757–4764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saarnio J, Parkkila S, Parkkila AK, Waheed A, Casey MC, Zhou XY, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Karttunen T, Haukipuro K, Kairaluoma MI, Sly WS. Immunohistochemistry of carbonic anhydrase isozyme IX (MN/CA IX) in human gut reveals polarized expression in the epithelial cells with the highest proliferative capacity. J. Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:497–504. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ivanov S, Liao SY, Ivanova A, Danilkovitch-Miagkova A, Tarasova N, Weirich G, Merrill MJ, Proescholdt MA, Oldfield EH, Lee J, Zavada J, Waheed A, Sly W, Lerman MI, Stanbridge EJ. Expression of hypoxia-inducible cell-surface transmembrane carbonic anhydrases in human cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:905–919. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kummola L, Hamalainen JM, Kivela J, Kivela AJ, Saarnio J, Karttunen T, Parkkila S. Expression of a novel carbonic anhydrase, CA XIII, in normal and neoplastic colorectal mucosa. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Alterio V, Hilvo M, Di Fiore A, Supuran CT, Pan P, Parkkila S, Scaloni A, Pastorek J, Pastorekova S, Pedone C, Scozzafava A, Monti SM, De Simone G. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the tumor-associated human carbonic anhydrase IX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:16233–16238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908301106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) De Simone G, Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrase IX: biochemical and crystallographic characterization of a novel antitumor target. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dubois L, Douma K, Supuran CT, Chiu RK, van Zandvoort MA, Pastorekova S, Scozzafava A, Wouters BG, Lambin P. Imaging the hypoxia surrogate marker CA IX requires expression and catalytic activity for binding fluorescent sulfonamide inhibitors. Radiother. Oncol. 2007;83:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Dubois L, Peeters SGJA, van Kuijk SJA, Yaromina A, Lieuwes NG, Saraya R, Biemans R, Rami M, Parvathaneni NK, Vullo D, Vooijs M, Supuran CT, Winum JY, Lambin P. Targeting carbonic anhydrase IX by nitroimidazole based sulfamides enhances the therapeutic effect of tumor irradiation: a new concept of dual targeting drugs. Radiother Oncol. 2013;108:523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrase: novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:168–181. doi: 10.1038/nrd2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Mahon BP, Hendon AM, Driscoll JM, Rankin GM, Poulsen SA, Supuran CT, McKenna R. Saccharin: a lead compound for structure-based drug design of carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ward C, Meehan J, Mullen P, Supuran C, Dixon JM, Thomas JS, Winum JY, Lambin P, Dubois L, Pavathaneni NK, Jarman EJ, Renshaw L, Um I, Kay C, Harrison DJ, Kunkler IH, Langdon SP. Evaluation of carbonic anhydrase IX as a therapeutic target for inhibition of breast cancer invasion and metastasis using a series of in vitro breast cancer models. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24856–24870. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Lock FE, McDonald PC, Lou Y, Serrano I, Chafe SC, Ostlund C, Aparicio S, Winum JY, Supuran CT, Dedhar S. Targeting carbonic anhydrase IX depletes breast cancer stem cells within the hypoxic niche. Oncogene. 2013;32:5210–5219. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lou Y, McDonald PC, Oloumi A, Chia S, Ostlund C, Ahmadi A, Kyle A, Auf dem Keller U, Leung S, Huntsman D, Clarke B, Sutherland BW, Waterhouse D, Bally M, Roskelley C, Overall CM, Minchinton A, Pacchiano F, Carta F, Scozzafava A, Touisni N, Winum JY, Supuran CT, Dedhar S. Targeting tumor hypoxia: suppression of breast tumor growth and metastasis by novel carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3364–3376. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pacchiano F, Carta F, McDonald PC, Lou Y, Vullo D, Scozzafava A, Dedhar S, Supuran CT. Ureido-substituted benzenesulfonamides potently inhibit carbonic anhydrase IX and show antimetastatic activity in a model of breast cancer metastasis. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:1896–1902. doi: 10.1021/jm101541x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Supuran CT, Winum JY. Designing carbonic anhydrase inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015;10:591–597. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2015.1038235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Supuran CT, Winum JY. Carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors in cancer therapy: an update. Future Med. Chem. 2015;7:1407–1414. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hsieh MJ, Chen KS, Chiou HL, Hsieh YS. Carbonic anhydrase XII promotes invasion and migration ability of MDA MB231 breast cancer through the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2010;89:598–606. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Thiry A, Dogne JM, Supuran CT, Masereel B. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors as anticonvulsant agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:855–864. doi: 10.2174/156802607780636726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrases–an overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14:603–614. doi: 10.2174/138161208783877884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Supuran CT. Structure-based drug discovery of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2012;27:759–772. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2012.672983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher SZ, Maupin CM, Budayova-Spano M, Govindasamy L, Tu C, Agbandje-McKenna M, Silverman DN, Voth GA, McKenna R. Atomic crystal and molecular dynamics simulation structures of human carbonic anhydrase II: insights into the proton transfer mechanism. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2930–2937. doi: 10.1021/bi062066y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Pinard MA, Mahon B, McKenna R. Probing the surface of human carbonic anhydrase for clues towards the design of isoform specific inhibitors. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015;2015:45–3543. doi: 10.1155/2015/453543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aggarwal M, Kondeti B, McKenna R. Insights towards sulfonamide drug specificity in alpha-carbonic anhydrases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:1526–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Supuran CT. How many carbonic anhydrase inhibition mechanisms exist? J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016;31:345–360. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2015.1122001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moeker J, Mahon BP, Bornaghi LF, Vullo D, Supuran CT, McKenna R, Poulsen SA. Structural insights into carbonic anhydrase IX isoform specificity of carbohydrate-based sulfamates. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:8635–8645. doi: 10.1021/jm5012935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacchiano F, Aggarwal M, Avvaru BS, Robbins AH, Scozzafava A, McKenna R, Supuran CT. Selective hydrophobic pocket binding observed within the carbonic anhydrase II active site accommodate different 4- substituted-ureido-benzenesulfonamides and correlate to inhibitor potency. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2010;46:8371–8373. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02707c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Mikulski R, West D, Sippel KH, Avvaru BS, Aggarwal M, Tu C, McKenna R, Silverman DN. Water networks in fast proton transfer during catalysis by human carbonic anhydrase II. Biochemistry. 2013;52:125–131. doi: 10.1021/bi301099k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Avvaru BS, Kim CU, Sippel KH, Gruner SM, Agbandje-McKenna M, Silverman DN, McKenna R. A short, strong hydrogen bond in the active site of human carbonic anhydrase II. Biochemistry. 2010;49:249–251. doi: 10.1021/bi902007b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sippel KH, Robbins AH, Domsic J, Genis C, Agbandje-McKenna M, McKenna R. High-resolution structure of human carbonic anhydrase II complexed with acetazolamide reveals insights into inhibitor drug design. Acta Crystallogr. F. 2009;65:992–995. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109036665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahon BP, Lomelino CL, Ladwig J, Rankin GM, Driscoll JM, Salguero AL, Pinard MA, Vullo D, Supuran CT, Poulsen SA, McKenna R. Mapping selective inhibition of the cancer-related carbonic anhydrase IX using structure-activity relationships of glucosyl-based sulfamates. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:6630–6638. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saarnio J, Parkkila S, Parkkila AK, Haukipuro K, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Kairaluoma MI, Karttunen TJ. Immunohistochemical study of colorectal tumors for expression of a novel transmembrane carbonic anhydrase, MN/CA IX, with potential value as a marker of cell proliferation. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;153:279–285. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Genis C, Sippel KH, Case N, Cao W, Avvaru BS, Tartaglia LJ, Govindasamy L, Tu C, Agbandje-McKenna M, Silverman DN, Rosser CJ, McKenna R. Design of a carbonic anhydrase IX active-site mimic to screen inhibitors for possible anticancer properties. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1322–1331. doi: 10.1021/bi802035f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pinard MA, Boone CD, Rife BD, Supuran CT, McKenna R. Structural study of interaction between brinzolamide and dorzolamide inhibition of human carbonic anhydrases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:7210–7215. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Debreczeni JE, Emsley P. Handling ligands with coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:425–430. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.