Abstract

Background

Leaf blight caused by Calonectria spp. is one of the most destructive diseases to affect Eucalyptus nurseries and plantations. These pathogens mainly attack Eucalyptus, a tree with a diversity of secondary metabolites employed as defense-related phytoalexins. To unravel the fungal adaptive mechanisms to various phytoalexins, we examined the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii, which is one of the most aggressive pathogens in southeast Asia.

Results

A 63.7 Mb genome with 14,355 coding genes of C. pseudoreteaudii were assembled. Genomic comparisons identified 1785 species-specific gene families in C. pseudoreteaudii. Most of them were not annotated and those annotated genes were enriched in peptidase activity, pathogenesis, oxidoreductase activity, etc. RNA-seq showed that 4425 genes were differentially expressed on the eucalyptus(the resistant cultivar E. grandis×E.camaldulensis M1) tissue induced medium. The annotation of GO term and KEGG pathway indicated that some of the differential expression genes were involved in detoxification and transportation, such as genes encoding ABC transporters, degrading enzymes of aromatic compounds and so on.

Conclusions

Potential genomic determinants of phytoalexin detoxification were identified in C. pseudoreteaudii by comparison with 13 other fungi. This pathogen seems to employ membrane transporters and degradation enzymes to detoxify Eucalyptus phytoalexins. Remarkably, the Calonectria genome possesses a surprising number of secondary metabolism backbone enzyme genes involving toxin biosynthesis. It is also especially suited for cutin and lignin degradation. This indicates that toxin and cell wall degrading enzymes may act important roles in the establishment of Calonectria leaf blight. This study provides further understanding on the mechanism of pathogenesis in Calonectria.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-4739-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Eucalyptus, Calonectria leaf blight, Detoxification, Secondary metabolism, Cell wall degrading enzymes

Background

The genus Calonectria (anamorph state: Cylindrocladium) includes a group of pathogens commonly found in tropical and sub-tropical regions [1–3]. They can infect more than 335 plant species, causing serious economic losses in forestry, agricultural and horticultural crops [4–7]. Eucalyptus species are among the main hosts of these pathogens, as they can attack Eucalyptus leaf, stem, and branch tissues (Fig. 1a-c), establishing CLBs, stem cancer and cutting rot [8, 9]. Of these, CLBs are the most devastating diseases in Eucalyptus nurseries and plantations [10–12].

Fig. 1.

Infection of C. pseudoreteaudii on Eucalyptus tree. a-c. Symptoms of C. pseudoreteaudii on Eucalyptus leaf and twigs, including leaf blight and stem cankers. d. Defoliated Eucalyptus trees caused by C. pseudoreteaudii in a plantation

The Calonectria genus comprises at least 68 species that are further classified into 13 groups according to the morphological features and DNA sequences [3, 13]. C. reteaudii complex are the causal agents of CLBs in Australia, South America and Southeast Asia [14]. This complex currently includes six described species, including C. microconidialis, C. pentaseptata, C. pseudoreteaudii, C. queenslandica, C. reteaudii and C. terrae-reginae [12, 13]. They share a common feature in that their anamorphs Cylindrocladium all have a clavate vesicle with multiseptate macroconidia. Of these species, C. pseudoreteaudii is the first species of this genus found in Fujian province, China. It is also one of the most widely-distributed and aggressive species in this region [15]. C. pseudoreteaudii infects Eucalyptus tissue mainly by conidia [16]. Infected leaf symptoms begin with water-soaked lesions, which rapidly develop into extensive tissue maceration and necrosis under high humidity condition, resulting in leaf blotch and shoot blight and leading to serious defoliation and eventually death (Fig. 1d). It is estimated that annual economic losses due to this disease are over $7.8 million in Fujian alone [17].

Recently, whole genome sequencing has been employed in the study of plant pathogenic fungi [18]. This technology with the application of comparative genomics analysis has accelerated the study of plant pathogens and significantly advanced our understanding of different pathogens [19–21]. To date, over 100 plant pathogenic fungi and oomycetes have completed genome sequencing. The results indicate remarkable diversity in genome size and architecture of pathogens with various ecological niches and lifestyles [22, 23]. Some pathogens tend to evolve smaller genomes than their free-living relatives, while others exhibit a trend towards larger genomes by increasing repetitive DNA. Variations in genome size are always accompanied by expansions and contractions of specific gene families [22, 24, 25]. Obligate biotrophic pathogens such as rust fungi, powdery mildews, and downy mildews have a reduced set of genes encoding plant cell wall hydrolases. Necrotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens seem to expand gene families involved in plant cell wall degradation and secondary metabolism [26, 27]. Moreover, phytopathogenic fungi always evolve an appropriate genome to adapt to specific ecological niches. For example, Ustilaginoidea virens has an adaptation to occupy host florets by reducing gene inventories for polysaccharide degradation, nutrient uptake, and secondary metabolism [28].

In classification, Calonectria belongs to Nectriaceae family. So far, many species of this family have completed genome sequences, for example, Fusarium spp. and Neonectria ditissima [29–32]. Genomic analysis of Nectria haematococca (F. solani) indicated three supernumerary chromosomes which could account for individual isolates having different environmental niches [33]. Comparative genomics of F. oxysporum with other Fusarium spp. revealed LSGR rich in transposons and genes related to pathogenicity [34]. This entire LSGR can transfer between strains of F. oxysporum, and convert a non-pathogenic strain into a pathogen [35]. However, an investigation has not been performed on the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii, or other Calonectria species.

Given the economic importance of Eucalyptus, we sequenced the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii and analyzed its transcriptome cultured on Eucalyptus tissue medium and PDB, respectively. This can promote our understanding on the pathogenicity mechanism and provide reference for developing effective disease management strategies.

Results and discussion

Genome sequencing and general features

The genome of C. pseudoreteaudii YA51 was sequenced using Illumina Hiseq sequencing platform. The total reads were 13,584 Mb in length, representing an approximate 213-fold sequence coverage (Additional file 1: Table S1). A 63.57 Mb draft genome was assembled with 507 scaffolds (>500 bp; Table 1). Scaffold N50 is 1.32 Mb and the largest scaffold is 5.15 Mb. CEGMA analysis indicated that 240 out of 248 (96.7%) core eukaryotic genes were identified in the C. pseudoreteaudii genome. This suggests a high degree of completeness for the C. pseudoreteaudii genome assembly. The estimated proportion of repeat sequences in C. pseudoreteaudii is 9.26% (Additional file 1: Table S2). Most of these repetitive sequences (91.8%) are TEs. Similar to other fungi, the C. pseudoreteaudii genome includes a large proportion Gypsy and Copia retrotransposons.

Table 1.

The general features of C. pseudoreteaudii

| Feature | C. pseudoreteaudii |

|---|---|

| Assembly size (Mb) | 63.7 |

| Coverage (fold) | 213.2 |

| Scaffold number | 507 |

| N50 scaffold (kb) | 1316 |

| N90 scaffold (kb) | 261 |

| GC content(%) | 48.3 |

| Repeat rate (%) | 9.27 |

| Gene number | 14,355 |

| Gene density (genes· Mb−1) | 225 |

| Average gene length (bp) | 1514.8 |

| Number of exons | 40,210 |

| Average number of exons per gene | 2.8 |

| Average exon size (bp) | 487.6 |

| Number of Introns | 25,855 |

| Average number of intron per gene | 1.8 |

| Average intron size (bp) | 82.7 |

| tRNA genes | 370 |

| Secreted proteins | 1178 |

| SSCRPs | 207 |

| Genbank accession number | MOCD00000000 |

A total of 14,355 genes including 1178 secreted protein genes were predicted from the annotated C. pseudoreteaudii genome, 87% of which were supported by RNA-seq data. The coding capacities were similar to those of other ascomycetes such as F. solani and N. ditissima [22, 36]. Among these proteins, 11,636 (81.05%) were similar to the sequences in NCBI, 4298 (29.94%) were mapped to the KEGG database, 11,760 (81.92%) were classified in the NOG database (Additional file 2: Figure S1), and 8972 (62.5%) were assigned to GO terms (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Phylogeny and analysis of gene families

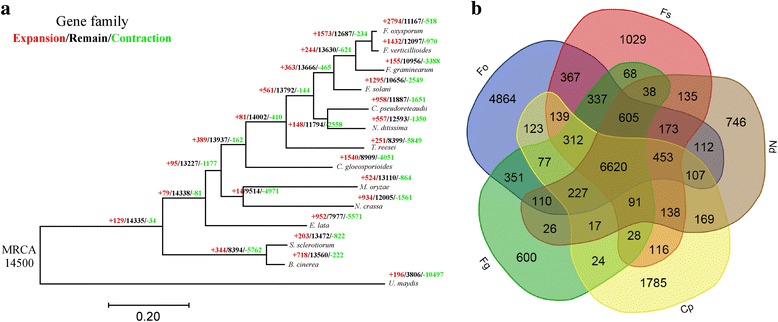

The phylogenetic position of C. pseudoreteaudii was evaluated among 13 other fungal species (12 ascomycota and one basidiomycota outgroup) using 1032 highly conserved single-copy orthologous genes. Compared with other Nectriaceae fungi, C. pseudoreteaudii was more closely related to N. ditissima, which is an important pathogen on apples (Fig. 2a). We have identified 14,500 gene families in 14 organisms. More common gene families (169) shared by C. pseudoreteaudii and N. ditissima suggesting that these two relatives retained more common characteristics (Fig. 2b). In addition, there were 1785 species-specific gene families (including 1828 genes) in C. pseudoreteaudii. However, most of them were not annotated due to a lack of homology with proteins in the pfam database. We speculate that these genes may have recently formed to adapt to a specific host. Those annotated species-specific genes were enriched in several functional items (Additional file 2: Figure S3): peptidase activity, pathogenesis, oxidoreductase activity, etc.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship and analysis of gene families. a. Phylogenetic analysis of C. pseudoreteaudii and 13 other ascomycota fungi. Predicted pattern of gain and loss of gene families in 14 organisms used in this study. The numbers on the branches of the phylogenetic tree correspond to acquired (left, red), conserved (middle, black), lost (right, green), by comparison with the putative pan-proteome. b. The numbers represent counts of gene families which are either specific to each species or common shared among multiple species. Cp, C. pseudoreteaudii; Nd, Neonectria ditissima; Fs, Fusarium solani; Fg, F. graminearum; Fo, F. oxysporum; Fv, F. verticillioides

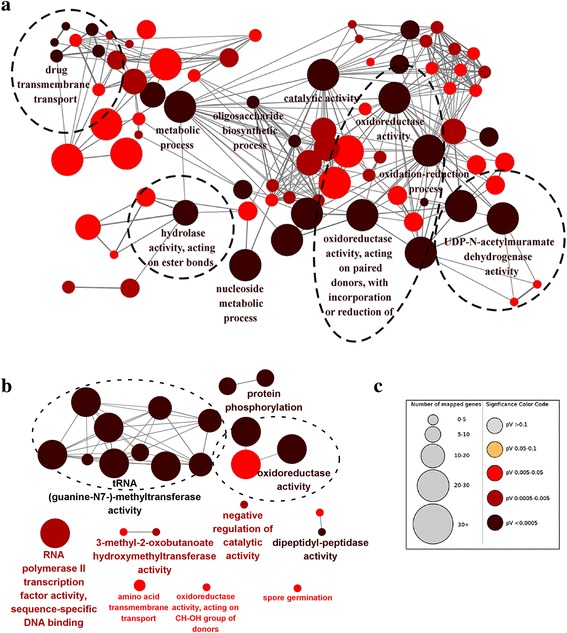

Compared with N. ditissima, 958 and 1651 gene families have been predicted to have experienced expansion or contraction in C. pseudoreteaudii, respectively (Fig. 2a). The GO analysis of significantly expanded and contracted gene families are showed in Fig. 3 (P < 0.01). The contracted gene families are functionally classified into tRNA methyltransferase activity, protein phosphorylation and oxidoreductase activity (Fig. 3b). Most of the expanded gene families are functionally classified into oxidation-reduction processes, suggesting a crucial role in the host adaptive process (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, three families with 16 members are related to cellular aromatic compound metabolic processes. 7 genes were involved in drug transmembrane transport. There were also some expanded genes related to hydrolase activity and UDP-N-acetylmuramate dehydrogenase activity (Additional file 2: Figure S4). We suggested that genes in these functional categories may play crucial role in the ecological adaptation of C. pseudoreteaudii.

Fig. 3.

GO analysis of the expanded and contracted gene families in C. pseudoreteaudii. a The expanded gene families were significantly enriched in oxidation-reduction processes, drug transmembrane transport, hydrolase activity and UDP-N-acetylmuramate dehydrogenase activity. b The contracted gene families were significantly enriched in tRNA methyltransferase activity, protein phosphorylation, and oxidoreductase activity. c Each circle represents a significantly enriched GO term (P < 0.05, hypergeometric test, Bonferroni step-down correction). The color code reflects P values and the circle size indicates the number of genes relative to each GO term

Transcriptome analyses

To identify genes and pathways that may involve in pathogenesis of C. pseudoreteaudii to E. grandis×E.camaldulensis M1, differentially expressed genes of C. pseudoreteaudii cultured on the eucalyptus (E. grandis×E.camaldulensis M1) tissue induced medium were analyzed with C. pseudoreteaudii cultured on the PDB medium as control.

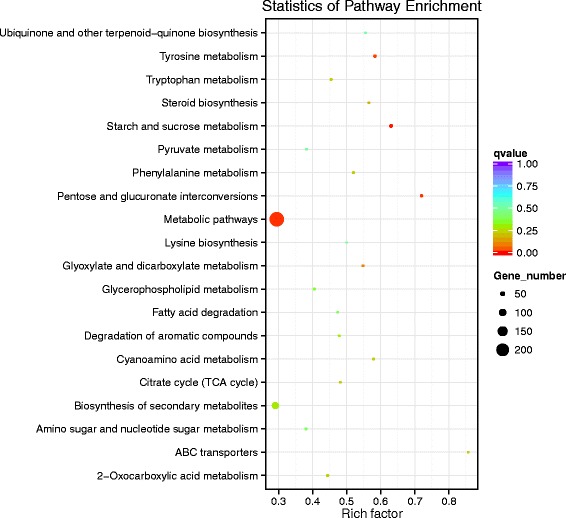

Totally, 33.05 Gb of sequence data were generated from 6 samples. 85% of the reads could be located on the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii. With P value < 0.05 and log2(fold change) ≥1 as the parameter, 1726 and 2699 genes were found to up-regulate and down-regulate on induced medium, respectively. To provide a general view on the functions and processes, differentially expressed genes were annotated in GO term and KEGG pathways. The result indicated that there were several significantly enriched terms of up-regulated genes including transporter activity, polygalacturonase activity, transcription factor activity, copper ion transmembrane transporter activity, oxidoreductase activity, etc. (Additional file 2: Figure S5a). While there were no significantly terms of down-regulated genes (Additional file 2: Figure S5b). KEGG pathway analysis showed that these differentially expressed genes were involved in ABC transporters, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, starch and sucrose metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, degradation of aromatic compounds and so on (Fig. 4). The more down-regulated genes suggested that the cultivar eucalyptus tissue caused stress to the growth of C. pseudoreteaudii. Previous research has indicated that polyphenols and flavonoids were important defensive compounds on the resistance of Eucalyptus to Calonectira [37]. Thus, these defensive compounds could be one source of the growth stress of C. pseudoreteaudii in induced medium. While C. pseudoreteaudii could clear defensive compounds from host by degradation, or segregate them by transporter, then relieve the growth stress from host.

Fig. 4.

KEGG pathway analysis of differentlly expressed genes of C. pseudoreteaudii in Eucalyptus tissue medium culture. The differentlly expressed genes (log2 fold-changes) were significantly enriched in ABC transporters, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, starch and sucrose metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, degradation of aromatic compounds and so on

Genes involved in secondary metabolism are remarkably expanded in C. pseudoreteaudii

Filamentous fungi produce a diverse array of secondary metabolites during their development. Phytopathogens employ secondary metabolites as weapons to facilitate the invasion and colonization, including polyketides, nonribosomal peptides, terpenes, etc. [38, 39]. Backbone enzymes are primarily responsible for the synthesis of these metabolites. In this study, we identified 57 backbone enzyme genes in the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii, including 25 PKS, 26 NRPS, and 2 DMAT (Table 2, Additional file 1: Table S3), which was more than the average level for ascomycete [26]. It suggested a great production capacity of secondary metabolites in C. pseudoreteaudii. RNA-seq showed that seven of these were up-regulated in mycelia of Eucalyptus tissue medium culture, including three NPRS and four PKS genes. One PKS gene (Cp_Cap07289), annotated as a putative conidial pigment polyketide synthase, was up-regulated during infection with Eucalyptus leaves.

Table 2.

The backbone genes responsible for the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites

| Species | NRPSa | PKSb | HYBRIDc | DMATd | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calonectria pseudoreteaudii | 26 | 25 | 4 | 2 | 57 |

| Fusarium graminearum | 21 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 37 |

| Magnaporthe oryzae | 11 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 32 |

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum | 10 | 18 | 0 | 1 | 29 |

| Neurospora crassa | 6 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 15 |

| Trichoderma reesei | 13 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 27 |

aNRPS denotes nonribosomal peptide synthases; bPKS denotes polyketide synthases; cHYBRID denotes NRPS-PKS; dDMAT dimethylallyl tryptophan synthases

The biosynthesis of secondary metabolites also requires modifying enzymes, such as dehydrogenases, methyl-transferases, and CYPs [40]. CYP enzymes catalyze the conversion of hydrophobic intermediates from primary and secondary metabolic pathways and detoxify natural and synthetic antifungal compounds, allowing fungi to grow under different conditions [41]. A total of 161 CYPs were identified in the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii. 20 of which were up-regulated in Eucalyptus tissue medium culture and nine were unique to C. pseudoreteaudii.

The backbone enzymes genes of secondary metabolism, and other related genes including modified enzyme genes, regulatory genes and transporter genes, are typically closely clustered in the genome [42, 43]. Therefore, it is important to identify secondary metabolism gene cluster. 35 gene clusters involved in secondary metabolism were found in the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii (Additional file 1: Table S4). 22% of which contained at least one transporter. Overall ten CYP genes were found within these gene clusters.

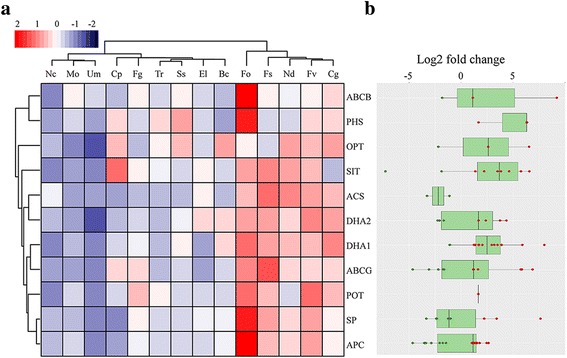

Transport capacity is enhanced in C. pseudoreteaudii

Membrane transporters can function in the transport of nutrients and removal of toxic compounds. We identified 679 membrane transporter genes in the C. pseudoreteaudii genome (Additional file 1: Table S5), which is about the same as F. solani and F. verticillioides. However, C. pseudoreteaudii contains more ABC transporters compared with the 13 other fungi. ABC transporter is a virulence factor that increases tolerance of the pathogen by extruding the natural and synthetic toxins from the cell. Several subfamilies of MFS transporters expanded in the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii, such as SITs (Fig. 5a). SITs can help pathogens to overcome iron limitations, and enhance pathogenicity [44, 45]. This suggests that ABC and MFS transporters may play a role in C. pseudoreteaudii during adaptation to the specific niche.

Fig. 5.

Comparison and expression patterns of membrane transporter families in C. pseudoreteaudii and 13 ascomycota fungi. a. Hierarchical clustering of membrane transporter families from C. pseudoreteaudii and 13 fungal genomes. Tr, Trichoderma reesei; El, Eutypa lata; Cg, Colletotrichum graminicola; Nc, Neurospora crassa; Mo, Magnaporthe oryzae; Ss, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum; Bc, Botrytis cinerea; Ud, Ustilago maydis. Transporter families are represented by their family names according to the Transporter Collection Database (www.tcdb.org). Overrepresented (pink to red) and underrepresented (gray to blue) domains are depicted as Z-scores for each family. Approximately unbiased (AU) P-values (%) are computed by 1000 bootstrap resamplings by using the R package pvclust. b. Box-plot of gene expression of members in each membrane transporter family of C. pseudoreteaudii in Eucalyptus tissue medium culture (log2 fold-changes). The Tukey whiskers indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles

RNA-seq data showed that 105 membrane transporters were significantly up-regulated on the Eucalyptus tissue medium culture (Additional file 1: Table S6). Interestingly, most of them were MFS transporters including SITs and DHA1 (Fig. 5b). DHA1 is also reported to transport specific drugs and confer multidrug resistance of pathogens [46]. These results further illuminated that this pathogen possibly enhanced transport capability to colonize a host niche that is enriched in antifungal compounds.

C. pseudoreteaudii genome is suited for cutin and lignin degradation

The plant cuticle is the outermost defense against pathogens. In a previous study, the cuticle thickness is a key factor for Eucalyptus against Calonectria [47]. However, the production of cutinase in the early infection can facilitate the penetration of the cuticle [48]. Remarkably, the C. pseudoreteaudii genome contains more cutinase genes than most of the fungi in this study (Additional file 1: Table S7), suggesting an enhanced potential for cuticle degradation. Cutinase genes were not significantly expressed on the Eucalyptus tissue medium culture. This could be attributed to the destruction of the cuticle in the medium. However, one cutinase gene (Ca_Cap05169) in C. pseudoreteaudii was up-regulated > 225-fold early in leaf infection [49].

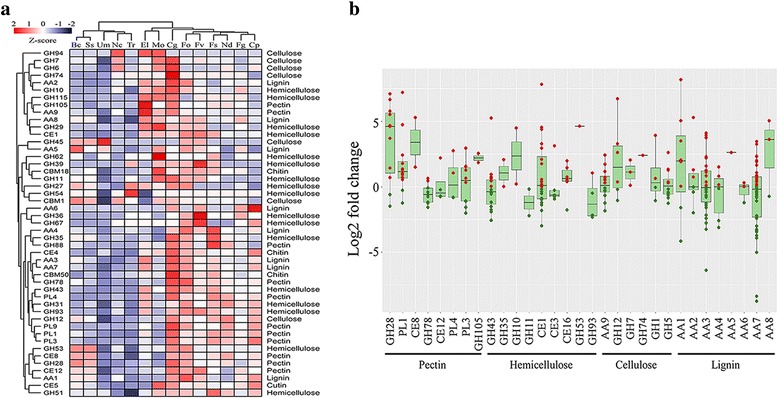

C. pseudoreteaudii possesses more genes encoding the 1,4-benzoquinone reductase (family AA6) that function in the degradation of lignin and in the protection of fungal cells from reactive quinone compounds (Fig. 6a; Additional file 1: Table S7). In addition, C. pseudoreteaudii has more genes encoding multicopper oxidases (AA1) than most other ascomycetes pathogens. Most of these genes were up-regulated in Eucalyptus tissue medium culture (Fig. 5b), indicating a high potential for lignin-degradation.

Fig. 6.

Cell wall degrading enzyme (CWDE) families in C. pseudoreteaudii. a. Hierarchical clustering of CWDE families from C. pseudoreteaudii and 13 fungal genomes. For fungi name abbreviations, see Fig. 2 and Fig. 4. Enzyme families are represented by their family number according to the carbohydrate-active enzyme database (http://www.cazy.org/). GH, glycoside hydrolase; CE, carbohydrate esterase; AA, auxiliary activities; CBM, carbohydrate-binding module; PL, polysaccharide lyase. Right side, known substrate of CWDE families. Overrepresented (white to red) and underrepresented (white to blue) domains are depicted as Z-scores for each family. Approximately unbiased (AU) P-values (%) are computed by 1000 bootstrap resamplings by using the R package pvclust. b. Plots of CWDE gene expression of each family in Eucalyptus tissue medium. Red circles, log2foldchange > 0; green circles, log2foldchange < 0. The substrates of CWDE families are indicated. The Tukey whiskers indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles

Likewise, C. pseudoreteaudii had more pectin-degrading enzyme genes than other pathogens, including families GH28, PL3, PL11, and PL22 (Fig. 6a; Additional file 1: Table S7). Many of these pectinase genes were significantly up-regulated in Eucalyptus tissue medium culture. 12 genes of GH28 family were found in the C. pseudoreteaudii genome, many of which were up-regulated more than tenfold (Fig. 6b). Furthermore, one polygalacturonase gene (Ca_Cap14295) was up-regulated > 500-fold during the infection of Eucalyptus leaves [49]. These results imply that pectinase may play important role in the colonization of C. pseudoreteaudii on Eucalyptus leaves.

C. pseudoreteaudii secretome is rich in potential virulence factors

Secreted proteins, particularly effectors, are essential for phytopathogens during their interactions with plants [24, 50, 51]. These proteins can degrade plant cell walls components or other substrates to facilitate the infection and the nourishment acquisition. They can also manipulate the environment of host cell to promote infection or elicit plant defense responses. In the current study, a total of 1178 secreted proteins were predicted in the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii, accounting for 8.2% of the proteome. These secreted proteins were significantly enriched in hydrolase activity, proteolysis, UDP-N-acetylmuramate dehydrogenase activity, cellulase activity, ferric iron binding, peroxidase activity, and cell wall macromolecule catabolic processes (Additional file 2: Figure S4).

Most of the identified pathogenic effectors are usually SSCPs. The disulfide bridges of partial cysteine residues can stabilize the structure and maintain the function of protein when transferred into the hostile environment of host cells [52]. Therefore, they play important roles in the compatible interaction with the host. In total, we found 207 SSCPs with lengths shorter than 300 amino acids and at least four cysteine residues in the mature proteins in C.pseudoreteaudii (Additional file 1: Table S8). Two SSCPs (Cp_Cap02912, Cp_Cap04435) had homologs with the LysM domain-containing proteins, which may play roles in the sequestration of chitin oligosaccharides and in dampening host defense [53]. Five of these SSCPs were up-regulated during infection of Eucalyptus [49].

Conclusions

In this study, we sequenced the genome of C. pseudoreteaudii, a pathogen that is extensively distributed throughout southeast Asia. A 63.7 Mb genome with 14,355 coding genes were assembled. The genome size and coding capacity is similar to related species. The genome contains 9.26% repeat sequences, most of which are TEs. Comparative genomic analysis has led to the conclusion that C. pseudoreteaudii has evolved multiple strategies to adapt to the hostile ecological habitat of Eucalyptus.

Eucalyptus species have diverse and abundant secondary metabolites for defense against various pathogens. The recently released genome of E. grandis revealed that it has the largest observed number of terpene synthase gene among all sequenced plant genomes [54]. Furthermore, several phenylpropanoid gene families and a subgroup of R2R3-MYB transcription factor genes, known to be involved in the regulation of the phenylpropanoid pathway, are significantly expanded by tandem duplications. This indicates that Eucalyptus can produce a wide range of terpenoid and phenylpropanoid-derived compounds for defense. Thus, successful colonization of the pathogen in Eucalyptus leaves largely depends on the pathogen’s ability to metabolize or inactivate these phytoalexins. A striking feature of the C.pseudoreteaudii genome is the numerous genes that degrade secondary metabolites, such as tannase, (S)-2-hydroxy-acid oxidase, Cytochrome P450, and aromatic amino acid aminotransferases. Some transporter families relating with the removal of toxic compounds were observed to expand in the C.pseudoreteaudii genome. This suggested that C. pseudoreteaudii probably developed an effective detoxification system, including degradation and transportation to respond to the phytoalexin enriched in Eucalyptus.

Fusarium is a closely related genus to C. pseudoreteaudii, and employs a diversity of secondary metabolites as toxins during the host interaction. There are three types of mycotoxins: polyketides, including aurofusarin, fumonisin and zearalenone; terpenes, including trichothecene and carotenoid; and nonribosomal peptides, including siderophorethe [55]. These mycotoxins increase membrane permeability and lead to water loss in the host. They can also alter the cell’s organellar structures and function, influence enzyme activities, inhibit protein synthesis, and trigger PCD [56]. Toxin production is essential for some diseases to spread in hosts. For example, wheat and toxin sensitivity is positively correlated with wheat cultivar susceptibility and pathogenesis [57]. Surprisingly, an analysis of secondary metabolism gene clusters in the C. pseudoreteaudii genome revealed a significant expansion of secondary metabolites. Thus, it is likely that this fungal pathogen produces some secondary metabolites employed as toxins that lead to the characteristic symptoms of leaf blight. However, further research is necessary to elucidate the chemical nature and role of these putative secondary metabolites.

Compared to other pathogenic fungi, C. pseudoreteaudii harbors a large number of cutinase genes, indicative of a gene expansion to adapt to the host environment and facilitate plant cuticle degradation. This expansion of cutinase genes may be a reason that C. pseudoreteaudii can attack the resistant cultivars of Eucalyptus which have thicker cuticle. Further supporting this notion, genes involved in the degradation of pectin and lignin were also more than other pathogens, consistent with C. pseudoreteaudii’s ability to spread to the branch tissue and cause cutting rot.

Methods

Sequenced strain

C. pseudoreteaudii YA51 strain was originally isolated from a Eucalyptus tree with the typical symptoms of leaf blight [15]. The sample was deposited at the Forestry protection institute, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, PR China (Deposited number: FAFUYA201105001). For genome sequencing, strain YA51 was cultured on PDA medium for 7 days, and then transferred to 150 mL PDB medium for 2 days. Mycelia were filtered through sterile gauze and lyophilized. Genomic DNA was extracted using SDS-CTAB and stored at − 80 °C.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome of C. pseudoreteaudii was sequenced using Illumina Hiseq platforms at Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Novogene, China). Three Illumina paired-end libraries were constructed with an insertion size of 500 bp, 2 kb, and 6 kb, respectively. Low-quality reads were filtered by Trimmomatic [58]. The high-quality reads were used for de novo assembly and scaffolding using SOAP denovo (version 1.05, http://soap.genomics.org.cn/soapdenovo.html). Gaps closure was performed using GapCloser v1.12 [59, 60]. The completeness of the C. pseudoreteaudii genome was evaluated using CEGMA [61]. Repeat sequences were identified and classified using RepeatModeler v1.07, RepeatProteinMask and RepeatMasker v4-0-3.

Gene prediction and annotation

Gene structure was predicted using the PASA pipeline with a combination of ab-initio and RNA-Seq evidence based approaches [62]. For ab-initio predictions, Augustus, SNAP, Transdecoder and GeneMark-ES v2 were employed to predict coding genes [63–65]. The EVidenceModeler (EVM) was used to compute weighted consensus gene annotations based on ab-initio gene models and transcript evidence derived from the Cufflinks RNA-seq assemblies in this study [62]. Finally, PASA was used again to update the EVM consensus prediction.

All predicted genes were functionally annotated by their sequence similarity to genes and proteins in several databases. For this, we used the BLASTp (e-value cutoff of 1e-5) to align the gene models against various proteins databases: non-redundant (NR) database at NCBI, SwissProt-databases containing only manually curated proteins, uniref90 and uniref100-databases containing clustered sets of proteins from UniProt, Pfam-database of protein families and KEGG-database of metabolic pathways. GO analysis of protein sequences were conducted by Blast2GO [66]. GO enrichment was performed by ClueGO with P value < 0.05 [67].

Phylogenomic tree construction

To construct the phylogenomic tree of C. pseudoreteaudii and 13 other ascomycota isolates, including Botrytis cinerea, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Eutypa lata, F. graminearum, F. oxysporum, F. solani, F. verticillioides, Magnaporthe oryzae, Neonectria ditissima, Neurospora crassa, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Trichoderma reesei and Ustilago maydis, 1032 single copy genes shared by all genomes were selected by orthofinder and aligned with mafft (mafft-linsi-anysymbol) [68, 69]. The phylogenomic tree was constructed using FastTree based on the alignments of single-copy ortholog families with approximately-maximum-likelihood model and bootstrap 100 [70].

Gene family analysis

Gene family annotation for C. pseudoreteaudii and the other organisms was based on a pfam local database with hmmer version 3.1b1 [71, 72]. The comparison of gene families across organisms was conducted by CAFE with lambda 0.314, P value 0.01 and 1000 random samples [73].

Putative CAZymes were identified using the HMMER 3.1b1 with annotated HMM profiles of CAZymes downloaded from the dbCAN database [74]. The identification and classification of the membrane transporters superfamily were obtained by using blastp searches with e value <1e-5 and identity > 40% against the transporter protein database, downloaded from Transporter Classification Database [75]. The secretomes of 14 fungi in this study were identified by SignalP 4.1 and TMHMM 2.0 [76]. Core secondary metabolite (SM) genes and clusters were initially identified using antiSMASH. CYPs genes were identified with HMMER and then named using the cytochrome P450 homepage [77].

Transcriptome analysis

C. pseudoreteaudii was cultured on PDB medium with 1% (w/v) Eucalyptus tissue (leaves of E. grandis ×E. camaldulensis M1 were ground into powder in liquid nitrogen using a mortar) for 2 days at 28 °C, 130 rpm. The mycelia were harvested with three biological replicates. Mycelia on PDB medium with no Eucalyptus tissue were used as control group.

Total RNA was extracted using RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech CO., LTD). The quality and quantity of RNA were determined using a Nanodrop2000 (Thermo, Wilmington, USA) and Agilent 2100. Six libraries were constructed as previously reported at Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Novogene, China). The insert sizes of all the libraries were 300 bp. They were sequenced with the Illumina HiSeq 2000 with 150 bp paired-end sequencing. All the clean reads were then mapped to the genome sequence of C. pseudoreteaudii using TopHat v 2.0.958 [78]. Gene expression levels were calculated using Cufflinks v2.0.266 based on the FPKM ([79]. Transcript with a significant P value (0.05) and a greater than two-fold change (log2) in transcript abundance was considered as differentially expressed gene.

Additional files

Table S1. Sequencing statistics of C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S2. Repeat sequences annotation of C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S3. Inventory of secondary metabolism backbone enzymes in C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S4. Inventory of secondary metabolism gene clusters in C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S5. Inventory of membrane transporters in C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S6. Upregulated (fold-change > 2) C. pseudoreteaudii membrane transporters in Eucalytpus tissue induced medium vs in PDB medium. Table S7. Number of carbohydrate-active enzyme modules of C. pseudoreteaudii and 13 other fungi according to the CAZy database. Table S8. Inventory of putative effectors in C. pseudoreteaudii. (XLS 238 kb)

Figure S1. Evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups (eggNOG) function annotation of the C. pseudoreteaudii genome. In total, there are 11,760 genes (81.92%) that have functional assignments. Figure S2. Gene ontology (GO) functional classification of the C. pseudoreteaudii genome. In total, there are 8972 genes (62.5%) that have functional assignments. Figure S3. Overrepresented GO categories of gene specific in C. pseudoreteaudii. Figure S4. GO term enrichment analysis of the expanded gene families in C. pseudoreteaudii. Figure S5. GO functional annotation of differentially expressed genes of C. pseudoreteaudii in Eucalyptus tissue medium culture (log2 fold-changes). a. Up-regulated genes. b. Down-regulated genes.The X- axis represents the number of genes in a functional group. (ZIP 12374 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jiandong Bao and Dr. Haiqiang Zhang for helpful technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project of Financial Department of Fujian Province (No. K81150002, K8112014A and K8113001A) and the fund of Jinshan College of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry university (No. Z150702).

Availability of data and materials

The Whole-Genome Shotgun project for C. pseudoreteaudii are deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number MOCD00000000. The raw sequence reads are deposited in NCBI SRA database under the accession number SRP090272.

Abbreviations

- AAs

Auxillary Activities

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- CAZymes

Carbohydrate-active enzymes

- CBMs

Carbohydrate-Binding Modules

- CE

Carbohydrate Esterases

- CEGMA

Core Eukaryotic Gene Mapping Approach

- CLBs

Calonectria leaf blight

- CYPs

Cytochrome P450

- DHA1

Drug: H+ Antiporter-1

- DMAT

Dimethylallyl tryptophan synthases

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of exon model per millions mapped reads

- GH

Glycoside Hydrolases

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GT

Glycosyl Transferases

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes

- LSGR

Lineage-specific genomic regions

- MFS

Multi-drug resistant transporters

- NOG

Non-Supervised Orthologous Groups

- NRPS

Nonribosomal peptide synthases

- PCD

Programmed cell death

- PDA

Potato dextrose agar

- PDB

Potato dextrose broth

- PKS

Polyketide synthases

- PL

Polysaccharide Lyases

- SDS-CTAB

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide

- SITs

Siderophore-iron transporters

- SSCPs

Cysteine-rich proteins

- TEs

Transposable elements

Authors’ contributions

GL, FZ, QC, and WG conceived the study. XY, HL, MG and QC prepared the strain samples and did the sequencing test. ZZ, LL, and HL conducted the bioinformatics analysis. XY, ZZ, GL, ZW, QZ, and LF prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12864-018-4739-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xiaozhen Ye, Email: lisayxz@163.com.

Zhenhui Zhong, Email: zhenhuizhong@gmail.com.

Hongyi Liu, Email: fjliuhongyi@126.com.

Lianyu Lin, Email: lianyulin.bio@gmail.com.

Mengmeng Guo, Email: fjguomm@126.com.

Wenshuo Guo, Email: fjgws@126.com.

Zonghua Wang, Email: wangzh@163.com.

Qinghua Zhang, Email: zhangqinghua13@163.com.

Lizhen Feng, Email: fjflz@126.com.

Guodong Lu, Email: guodonglu@yahoo.com.

Feiping Zhang, Email: fpzhang1@163.com.

Quanzhu Chen, Email: quanzhu0523@126.com.

References

- 1.Lombard L, Wingfield MJ, Alfenas AC, Crous PW. The forgotten Calonectria collection: pouring old wine into new bags. Stud Mycol. 2016;85:159–198. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lombard L, Crous PW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. Species concepts in Calonectria (Cylindrocladium) Stud Mycol. 2010;66:1–13. doi: 10.3114/sim.2010.66.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lombard L, Crous PW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. Phylogeny and systematics of the genus Calonectria. Stud Mycol. 2010;66:31–69. doi: 10.3114/sim.2010.66.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polizzi G, Vitale A, Aiello D, Guarnaccia V, Crous P, Lombard L. First report of Calonectria ilicicola causing a new disease on Laurus ( Laurus nobilis ) in Europe. J Phytopathol. 2012;160(1):41–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0434.2011.01852.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombard L, Rodas CA, Crous PW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. Calonectria (Cylindrocladium) species associated with dying Pinus cuttings. Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2009;23(6):41–47. doi: 10.3767/003158509X471052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirooka Y, Takeuchi J, Horie H, Natsuaki KT. Cylindrocladium brown leaf spot on Howea belmoreana caused by Calonectria ilicicola (anamorph: Cylindrocladium parasiticum) in Japan. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2008;74(1):66–70. doi: 10.1007/s10327-007-0068-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peerally A. The classification and phytopathology of Cylindrocladium species. Mycotaxon. 1991;40:323–366. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wingfield MJ, Slippers B, Hurley BP, Coutinho TA, Wingfield BD, Roux J. Eucalypt pests and diseases: growing threats to plantation productivity. Southern Forests A Journal of Forest Science. 2008;70(2):139–144. doi: 10.2989/SOUTH.FOR.2008.70.2.9.537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou XD, Xie YJ, Chen SF, Wingfield MJ. Diseases of eucalypt plantations in China: challenges and opportunities. Fungal Divers. 2008;32:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SF, Lombard L, Roux J, Xie YJ, Wingfield MJ, Zhou XD. Novel species of Calonectria associated with Eucalyptus leaf blight in Southeast China. Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2011;26(1):1–12. doi: 10.3767/003158511X555236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen QZ, Guo WS, Feng LZ, Miao SH, Lin JS. Identification of Calonectria associated with Eucalyptus spp. cutting seedling leaf blight. Journal of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University. 2013;42(3):257–262. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lombard L, Zhou XD, Crous PW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. Calonectria species associated with cutting rot of Eucalyptus. Persoonia - Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2010;24(1):1–11. doi: 10.3767/003158510X486568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lombard L, Chen SF, Mou X, Zhou XD, Crous PW, Wingfield MJ. New species, hyper-diversity and potential importance of Calonectria spp. from Eucalyptus in South China. Stud Mycol. 2015;80:151–188. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang JC, Crous PW, Old KM, Dudzinski MJ. Non-conspecificity of Cylindrocladium quinqueseptatum and Calonectria quinqueseptata based on a beta-tubulin gene phylogeny and morphology. Can J Bot. 2001;79(10):1241–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen QZ, Guo WS, Ye XZ, Feng LZ, Huang XP, Wu YZ. Identification of Calonectria associated with Eucalyptus leaf blight in Fujian province. Journal of Fujian Forestry College. 2013;33(02):176–182. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng MZ. Study on regularity of development of eucalyptus dieback. Journal of Fujian College of Forestry. 2006;26(4):339–343. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu JH, Guo WS, Chen HM, Wu JQ, Chen QZ, Meng XM. Loss estimation of eucalyptus growth caused by of eucalyptus dieback. Forest Pest and Disease. 2011;30(05):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thynne E, McDonald MC, Solomon PS. Phytopathogen emergence in the genomics era. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20(4):246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttman DS, McHardy AC, Schulze-Lefert P. Microbial genome-enabled insights into plant-microorganism interactions. NAT REV GENET. 2014;15(12):797–813. doi: 10.1038/nrg3748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong Y, Li Y, Qi Z, Zheng X, Zhang Z. Genome plasticity in filamentous plant pathogens contributes to the emergence of novel effectors and their cellular processes in the host. Curr Genet. 2016;62(1):47–51. doi: 10.1007/s00294-015-0509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DEAN R, VAN KAN JAL, PRETORIUS ZA, HAMMOND-KOSACK KE, DI PIETRO A, SPANU PD, et al. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13(4):414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raffaele S, Kamoun S. Genome evolution in filamentous plant pathogens: why bigger can be better. NAT REV MICROBIOL. 2012;10:417–30. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardiner DM, McDonald MC, Covarelli L, Solomon PS, Rusu AG, Marshall M, et al. Comparative pathogenomics reveals horizontally acquired novel virulence genes in fungi infecting cereal hosts. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(9):e1002952. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo PL, Lanver D, Schweizer G, Tanaka S, Liang L, Tollot M, et al. Fungal effectors and plant susceptibility. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2015;66:513–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-114623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubicek CP, Starr TL, Glass NL. Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes and their secretion in plant-pathogenic fungi. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2014;52:427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pusztahelyi T, Holb IJ, Pocsi I. Secondary metabolites in fungus-plant interactions. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:573. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang X, Jiang N, Liu J, Liu W, Wang GL. The role of effectors and host immunity in plant-necrotrophic fungal interactions. Virulence. 2014;5(7):722–732. doi: 10.4161/viru.29798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Zhang K, Fang A, Han Y, Yang J, Xue M, et al. Specific adaptation of Ustilaginoidea virens in occupying host florets revealed by comparative and functional genomics. NAT COMMUN. 2014;5:3849. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Jeong H, Lee S, Choi GJ, Lee T, Yun SH. Draft Genome Sequence of Fusarium fujikuroi B14, the Causal Agent of the Bakanae Disease of Rice. Genome Announc. 2013;1:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ma LJ, Geiser DM, Proctor RH, Rooney AP, O'Donnell K, Trail F, et al. Fusarium pathogenomics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013;67:399–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiemann P, Sieber CM, von Bargen KW, Studt L, Niehaus EM, Espino JJ, et al. Deciphering the cryptic genome: genome-wide analyses of the rice pathogen Fusarium fujikuroi reveal complex regulation of secondary metabolism and novel metabolites. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(6):e1003475. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rep M, Kistler HC. The genomic organization of plant pathogenicity in Fusarium species. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010;13(4):420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman JJ, Rounsley SD, Rodriguez-Carres M, Kuo A, Wasmann CC, Grimwood J, et al. The genome of Nectria haematococca: contribution of supernumerary chromosomes to gene expansion. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(8):e1000618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma LJ, van der Does HC, Borkovich KA, Coleman JJ, Daboussi MJ, Di Pietro A, et al. Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature. 2010;464(7287):367–373. doi: 10.1038/nature08850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vlaardingerbroek I, Beerens B, Rose L, Fokkens L, Cornelissen BJ, Rep M. Exchange of core chromosomes and horizontal transfer of lineage-specific chromosomes in Fusarium oxysporum. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(11):3702–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Gomez-Cortecero A, Harrison RJ, Armitage AD. Draft Genome Sequence of a European Isolate of the Apple Canker Pathogen Neonectria ditissima. Genome announcements. 2015;3:10–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Feng LZ, Chen QZ, Guo WS, Su L, Zhu JH. Relationship between Eucalyptus resistance to dieback and secondary metabolism. Chin J Eco-Agric. 2008;16(2):426–430. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1011.2008.00426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geng Z, Zhu W, Su H, Zhao Y, Zhang KQ, Yang J. Recent advances in genes involved in secondary metabolite synthesis, hyphal development, energy metabolism and pathogenicity in Fusarium graminearum (teleomorph Gibberella zeae) Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(2):390–402. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cole RJ, Jarvis BB, Schweikert MA. Handbook of secondary fungal metabolites (3-volume set) 1. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2003. pp. 527–542. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keller NP, Hohn TM. Metabolic pathway gene clusters in filamentous Fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21(1):17–29. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1997.0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guengerich FP, Waterman MR, Egli M. Recent structural insights into cytochrome P450 function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37(8):625–640. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osbourn A. Secondary metabolic gene clusters: evolutionary toolkits for chemical innovation. Trends Genet. 2010;26(10):449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keller NP. Translating biosynthetic gene clusters into fungal armor and weaponry. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(9):671–677. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moore MM. The crucial role of iron uptake in Aspergillus fumigatus virulence. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16(6):692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson L. Iron and siderophores in fungal-host interactions. Mycol Res. 2008;112(Pt 2):170–183. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sa-Correia I, Dos SS, Teixeira MC, Cabrito TR, Mira NP. Drug:H+ antiporters in chemical stress response in yeast. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng LZ, Liu YB, Guo SZ, Huang RH, Guo WS. Relationship between the leaf anatomical characteristics of Eucalyptus and its resistance to dieback. J Chin Electron Microsc Soc. 2008;27(3):229–234. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serrano M, Coluccia F, Torres M, L'Haridon F, Métraux JP. The cuticle and plant defense to pathogens. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:274. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye X, Liu H, Jin Y, Guo M, Huang A, Chen Q, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of Calonectria pseudoreteaudii during various stages of Eucalyptus infection. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e169598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morais DAA, Antoniw J, Rudd JJ, Hammond-Kosack KE. Defining the predicted protein secretome of the fungal wheat leaf pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e49904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown NA, Antoniw J, Hammond-Kosack KE. The predicted secretome of the plant pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum: a refined comparative analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e33731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stergiopoulos I, Collemare J, Mehrabi R, De Wit PJ. Phytotoxic secondary metabolites and peptides produced by plant pathogenic Dothideomycete fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37(1):67–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Jonge R, Thomma BP. Fungal LysM effectors: extinguishers of host immunity? Trends Microbiol. 2009;17(4):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Myburg AA, Dario G, Tuskan GA, Uffe H, Hayes RD, Jane G, et al. The genome of Eucalyptus grandis. Nature. 2014;510(7505):356–362. doi: 10.1038/nature13308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang XW, Dong Z. Recent advances of secondary metabolites in genus Fusarium. Plant Physiology Journal. 2013;49(3):201–216. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pestka JJ. Toxicological mechanisms and potential health effects of deoxynivalenol and nivalenol. World Mycotoxin J. 2010;3(4SI):323–347. doi: 10.3920/WMJ2010.1247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jansen C, von Wettstein D, Schafer W, Kogel KH, Felk A, Maier FJ. Infection patterns in barley and wheat spikes inoculated with wild-type and trichodiene synthase gene disrupted Fusarium graminearum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(46):16892–16897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508467102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li R, Zhu HJ, Qian W, Fang X, Shi Z, Li Y, et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 2010;20(2):265–272. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li R, Li Y, Kristiansen K, Wang J. Sequence analysis SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(5):713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parra G, Bradnam K, Korf I. CEGMA: a pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(9):1061–1067. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haas BJ, Zeng Q, Pearson MD, Cuomo CA, Wortman JR. Approaches to fungal genome annotation. Mycology. 2011;2(3):118–141. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2011.606851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC BIOINFORMATICS. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ter-Hovhannisyan V, Lomsadze A, Chernoff YO, Borodovsky M. Gene prediction in novel fungal genomes using an ab initio algorithm with unsupervised training. Genome Res. 2008;18(12):1979–1990. doi: 10.1101/gr.081612.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl 2):i215–i225. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gotz S, Garcia-Gomez JM, Terol J, Williams TD, Nagaraj SH, Nueda MJ, et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(10):3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Hackl H, Charoentong P, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology & Evolution. 2013;30(4):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Finn RD. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Finn RD, Jody C, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(8):W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth J, Hahn M. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(10):1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yanbin Y, Xizeng M, Jincai Y, Xin C, Fenglou M, Ying X. dbCAN: a web resource for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(WebServerissue):W451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saier MJ, Reddy VS, Tamang DG, Vastermark A. The transporter classification database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D251–D258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8(10):785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nelson DR. The cytochrome p450 homepage. HUM GENOMICS. 2009;4(1):59–65. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-1-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):295–311. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(3):562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Sequencing statistics of C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S2. Repeat sequences annotation of C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S3. Inventory of secondary metabolism backbone enzymes in C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S4. Inventory of secondary metabolism gene clusters in C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S5. Inventory of membrane transporters in C. pseudoreteaudii. Table S6. Upregulated (fold-change > 2) C. pseudoreteaudii membrane transporters in Eucalytpus tissue induced medium vs in PDB medium. Table S7. Number of carbohydrate-active enzyme modules of C. pseudoreteaudii and 13 other fungi according to the CAZy database. Table S8. Inventory of putative effectors in C. pseudoreteaudii. (XLS 238 kb)

Figure S1. Evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups (eggNOG) function annotation of the C. pseudoreteaudii genome. In total, there are 11,760 genes (81.92%) that have functional assignments. Figure S2. Gene ontology (GO) functional classification of the C. pseudoreteaudii genome. In total, there are 8972 genes (62.5%) that have functional assignments. Figure S3. Overrepresented GO categories of gene specific in C. pseudoreteaudii. Figure S4. GO term enrichment analysis of the expanded gene families in C. pseudoreteaudii. Figure S5. GO functional annotation of differentially expressed genes of C. pseudoreteaudii in Eucalyptus tissue medium culture (log2 fold-changes). a. Up-regulated genes. b. Down-regulated genes.The X- axis represents the number of genes in a functional group. (ZIP 12374 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The Whole-Genome Shotgun project for C. pseudoreteaudii are deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number MOCD00000000. The raw sequence reads are deposited in NCBI SRA database under the accession number SRP090272.