Abstract

Objective:

Minimal invasive endodontics preserve coronal and radicular tooth structure to increase the fracture resistance of teeth. The aim of this study was to assess the influence of final preparation taper on the fracture resistance of maxillary premolars.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty maxillary premolars were selected and divided into 2 groups: 30 were shaped with a final apical diameter 30 and a 4% taper and 30 with 6% taper using iRaCe® instrument (FKG dentaire, Switzerland). All root canals were irrigated with sodium hypochlorite and final rinse with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. All canals were filled with gutta-percha single-cone filling technique and AHPlus® sealer (Dentsply- Maillefer, Baillagues, Switzerland) and access cavity restored with resin composite. Roots were wax coated, placed in an acrylic mold and loaded to compressive strength fracture in a mechanical material testing machine recording the maximum load at fracture and fracture pattern (favorable/restorable or unfavorable/unrestorable). Fracture loads were compared statistically, and data examined with Student t-test with a level of significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results:

No statistically significant difference was registered between the 4% taper of preparation (270.47 ± 90.9 N) and 6% taper of preparation (244.73 ± 120.3 N) regarding the fracture resistance of the endodontically treated premolars tested (P = 0.541), while more favorable restorable fractures were registered in the 4% taper group.

Conclusions:

Continuous 4% preparation taper did not enhance the fracture resistance of endodontically treated maxillary premolars when compared to a 6% taper root canal preparation. More fractures were registered in the 4% taper group.

Keywords: Compressive strength, fracture resistance, maxillary premolars, minimally invasive endodontics, tapered preparation

INTRODUCTION

Endodontic treatment is a procedure that consists of several steps aiming to remove the diseased dental structures to preserve or heal the periapical tissues and guarantee the proper tooth function.[1] It is well established that endodontically treated teeth have a reduced resistance and higher susceptibility to fracture,[2,3] and this is mainly associated with the loss of dentinal structures following root canal treatment.[4]

According to the European Society of Endodontology, when a fracture involves enamel, dentine, or cementum, the tooth needs to be assessed for restorability.[5] As a matter of fact, root fracture has been reported as the third most common reason for extraction of an endodontically treated tooth, mostly affecting the premolars.[6] Shaping the root canal system has been subjected to variations and evolution during the last decades, and the endodontists were more and more encouraged to apply the concepts of minimally invasive dentistry to their shaping techniques, to preserve as much dental structures as possible.[7,8] Minimally invasive dentistry is the application of a systematic respect of the original tissue,[9] and its common delineator is represented by tissue preservation, preferably by preventing disease from occurring and intercepting its progress but also by removing and replacing pulpal tissues with conservative concerns and minimal damage.[10] Minimally invasive endodontics has been consequently suggested, consisting of smaller access cavities, minimal root canal preparations with an apical diameter ranging between 0.2 mm and 0.4 mm maximum, and a taper that is strictly below 6%.[8,11] Since the relationship between minimally invasive endodontics and fracture resistance is not yet well established,[12,13] the aim of the present study was to assess the influence of the final preparation taper on the fracture resistance of endodontically treated maxillary premolars. The null hypothesis tested was that there is no difference in the fracture resistance of maxillary premolars treated with a final preparation taper of 4% and 6%.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

SPECIMEN SELECTION AND PREPARATION

Sixty recently extracted, intact maxillary premolars with two separate roots were selected for this study. Teeth with caries, previous restoration, visible fracture lines or cracks, and open apices were excluded from the study. Samples were debrided by hand scaling and cleansed with a rubber cup and pumice and then stored in separate containers with 0.1% thymol solution to prevent dehydration before testing. Teeth were selected based on similar length and crown dimensions to minimize the influence of size and shape variations on the results. Similar access cavities were performed on all teeth using a #802 diamond bur and EndoZ bur (Dentsply-Maillefer, Baillagues, Switzerland) to locate root canals orifices. A #10 K-flexofile (Dentsply-Maillefer) was introduced with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid gel into each root canal to determine the working length (WL) and establish a glide path. Then, the 60 teeth were divided into 2 groups of 30 samples each.

SHAPING AND CLEANING THE ROOT CANAL SYSTEM

Group A

Thirty premolars were shaped with the iRace rotary instruments (FKG dentaire, Switzerland) reaching a final continuous 4% taper up to tip size 30, using the following files sequence: iRace tip size 10/.02 taper, iRace tip size 10/.04 taper, iRace tip size 15/.04 taper, iRace tip size 20/.04 taper, and iRace tip size 30/.04 taper. Instruments were used with an endodontic motor (X-Smart Plus, Dentsply Maillefer) following the manufacturer's instruction in continuous rotation at 600 rpm speed and with a maximum torque set at 2.0 N, with light apical pressure. During the shaping procedure, a #10 K-flexofile was taken to the WL to check patency, and irrigation with 2.5 mL of 5.25% NaOCl was performed with a syringe and an endodontic needle in each root canal after each instrument used.

Group B

Thirty premolars were shaped with the iRace rotary instruments reaching a final continuous 6% taper and an apical diameter of thirty, using the following files sequence: iRace tip size 10/.02 taper, iRace tip size 10/.04 taper, iRace tip size 10/.06 taper, iRace tip size 20/.06 taper, and iRace tip size 30/.06 taper. The same instrumentation procedures and irrigation protocol as Group A were used. When canal shaping was completed, 3 mL of distilled water were used to remove the remaining sodium hypochlorite, and a final flush with 2.5 mL SmearClear (SybronEndo, Orange, CA, USA) was performed in each root canal to eliminate the smear layer. Root canals were finally washed with 3mL saline solution and dried with paper points.

FILLING THE ROOT CANAL SYSTEM

Group A root canals were filled with the single cone technique using a gutta-percha cone tip size 30 and taper 4% with AHPlus® (Dentsply-Maillefer) resin root canal sealer.

Group B canals were filled with the single cone technique using a gutta-percha cone tip size 30 and taper 6% with AHPlus® (Dentsply-Maillefer) resin root canal sealer. In both groups, the prefitted master cone was coated with a thin layer of sealer and inserted into the canal till WL and then cut and compacted at the orifice with a heated plugger. All teeth were stored at 37°C with 100% humidity for 72 h.

SPECIMEN PREPARATION FOR THE UNIVERSAL TESTING MACHINE

Access cavities of all premolars from Groups A and B were then cleaned and filled with a resin composite (3M – ESPE). Specimen's roots were covered with 1 mm layer of wax positioned at 2 mm under the cement-enamel junction, thus simulating the periodontal ligament.[14] To replace the alveolar bone, teeth were placed into a squared mold of 8 cm of volume and a depth of 15 mm filled with acryl resin, with a light apical pressure completely covering the wax.

FRACTURE TEST

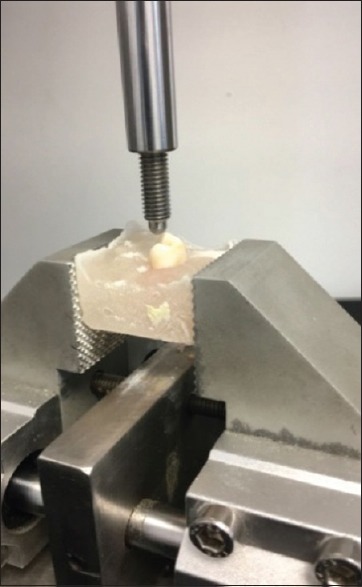

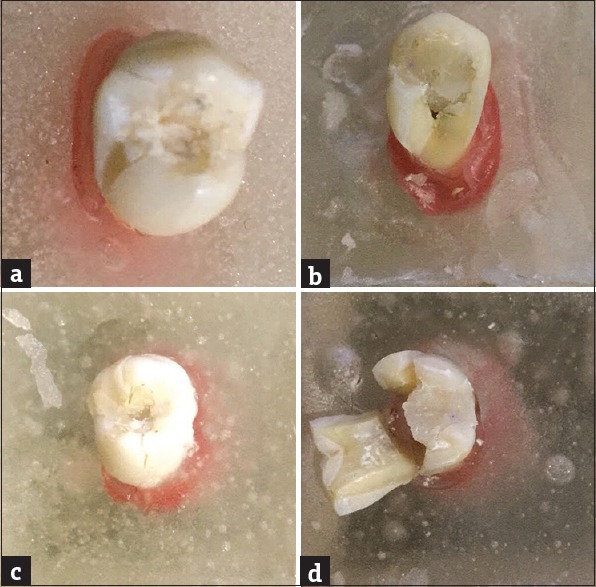

The 60 teeth specimens were placed in the YLE (GmbH Waldstraße Bad König, Germany) universal testing machine equipped with a 500 N cell load and loaded through a stainless-steel ball 3 mm in diameter at their central fossa, along with their long axis. The continuous compressive strength force was applied at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. The universal load-testing machine [Figure 1] was connected to a software that collected all the information and indicated the load at which each premolar tooth was fractured. Each fractured specimen was then examined to evaluate the fracture pattern [Figure 2] and classified as “favorable/restorable” when the failure was above the acrylic resin simulating the bone or “unfavorable/nonrestorable” when the failure was extending below the acrylic resin.[13]

Figure 1.

The universal testing machine YLE applying a compressive strength on a maxillary premolar until breakage

Figure 2.

Fracture patterns. (a) Restorable fracture of bicuspid with 4% tapered root canal preparation, (b) nonrestorable fracture of bicuspid with 4% tapered root canal preparation, (c) restorable fracture of bicuspid with 6% tapered root canal preparation, (d) nonrestorable fracture of bicuspid with 6% tapered root canal preparation

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

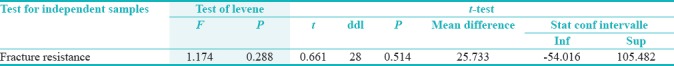

The “Statistical Package Software for Social Science” (SPSS for Windows, Version 20.0, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. The level of significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. The normality of distribution of the variable was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Levene test [Table 1]. Since the normality of the variable was approved, a parametrical test was applied and the Student's t-test was performed to compare the mean value of fracture resistance between 4% and 6% taper.

Table 1.

T-test and Levene test

RESULTS

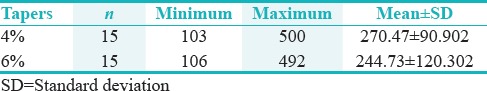

The mean values and standard deviations of the load at fracture for both groups are presented in Table 1. No statistically significant difference was registered between the 4% taper of preparation (270.47 ± 90.9 N) and 6% taper of preparation (244.73 ± 120.3 N) regarding the fracture resistance of the endodontically treated maxillary premolars tested (P = 0.541).

A statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in the number of favorable/restorable or unfavorable/nonrestorable fractures was observed between the two groups: the percentage of favorable/restorable tooth fractures was significantly higher in the 4% taper group rather than the 6% taper group [Table 2].

Table 2.

Mean values of breakage force in the 4% and 6% groups

DISCUSSION

Testing in vitro the load to fracture of endodontically treated teeth may help understand and evaluate their mechanical behavior. The present study was performed on maxillary premolars because they are more prone to fracture accordingly to other recent studies[15,16] by applying a static load through a universal testing machine.[13,14,15,16] However, fracture resistance methodology used for in vitro analysis does not accurately reflect intraoral conditions in which failures occur primarily from fatigue. In the same way, axial cyclically fatigued tests may not reflect complete root strain patterns for the complex chewing process.[17] In the present study, access cavities were restored with bonded resin composite to facilitate loading tests and to simulate clinical procedures because testing the teeth without any coronal restoration is far from the standard clinical practice.[13] One of the most important reasons of fracture in root-filled teeth is the loss of tooth structure. This may happen during all the phases of an endodontic treatment from the access cavity opening to the shaping procedures mainly depending on the taper and apical size of the preparation chosen. As a consequence, every step in endodontic treatment can lead to crack formation and breakage of the corresponding tooth.[18] For that concern, some studies reported a higher fracture resistance with an enlarged coronal access in comparison with the minimal enlarges ones[12,19] while others reported no differences if the teeth were properly restored.[13,17] For the shaping procedures, a previous study showed that increasing the root canal taper resulted in a lower fracture resistance; furthermore, it has been also reported that enlarging the taper of the preparation resulted in a higher stress due to masticatory forces.[20] The aim of the present study was to understand if a reduced tapered preparation following the concepts of minimally invasive endodontics might lead to an increased fracture resistance. Unlike the data obtained by Rundquist and Versluis in 2006,[20] the results of this study demonstrated that there was no statistical significant difference, in terms of fracture resistance, between the two different root canal preparations used: 4% taper and and 6% up to a tip size thirty. Thus, the null hypothesis may be accepted.

The difference with similar studies might be the result of variability in the applied methodology reflecting more difference in the study design rather that demonstrating a real clinical difference.[12] An axial fracture load was used in the present study because teeth are most vulnerable to fracture when eccentric forces are applied,[21] reaching the failure point at higher loads when compared with the 30° fracture loads of other studies.[22,23] Furthermore, the apical diameter in the preparation was limited in the present study to a size thirty. Further investigations should be conducted to evaluate the influence of different tapers in bigger apical sizes of preparation; situation in which this parameter may affect more drastically the fracture resistance of endodontically treated roots. Following the qualitative observation performed during the present study, our data showed that the 6% tapered preparations of the teeth were more in favor of coronoradicular fractures, especially in the cervical area (unrepairable fractures). The premolars instrumented with the 4% taper, however, registered a more preserved cervical region free of any fracture (repairable fractures). This may be obviously explained by the fact that smaller tapered preparations tend to decrease the stress on the cervical part of endodontically treated teeth more than the higher tapered preparations.[12] On the other hand, a minimal invasive approach and minimally treated teeth may represent an obstacle for disinfection.[19,24] Brunson et al. found that the 8% tapered root canals were better disinfected than the 4% ones with the same apical diameter of preparation.[25] These findings are also supported by another study of Khademi et al. in 2006 showing that bigger apical diameters of preparation resulted in a better apical disinfection.[26] As for the use of composite resin material for access cavity filling, our study was in concordance with the finding of Mincik in 2016 who found that composite restoration with cusp coverage was the most ideal nonprosthetic solution for endodontically treated teeth.[27]

CONCLUSIONS

Decreasing the taper of root canal preparation to 4% did not statistically increase the fracture resistance of endodontically treated maxillary premolars compared to a bigger 6% taper; the coronal maintenance of dentinal tooth structure affected the fracture behavior of the tested samples. Smaller tapers (4%) were directly related to more favorable and repairable registered fractures than larger ones. Further studies should be performed to investigate the quality of the instrumentation, the difficulties encountered during this procedure, and long-term prognosis of endodontically treated teeth following a minimal invasive approach.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schilder H. Filling root canals in three dimensions 1967. J Endod. 2006;32:281–90. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeh ES, Messer HH, Douglas WH. Reduction in tooth stiffness as a result of endodontic and restorative procedures. J Endod. 1989;15:512–6. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(89)80191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopal S, Irodi S, Mehta D, Subramanya S, Govindaraju VK. Fracture resistance of endodontically treated roots restored with fiber posts using different resin cements- an in-vitro study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:ZC52–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/21167.9387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ericson D. The concept of minimally invasive dentistry. Dent Update. 2007;34:9. doi: 10.12968/denu.2007.34.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Society of Endodontology. Quality guidelines for endodontic treatment: Consensus report of the European society of endodontology. Int Endod J. 2006;39:921–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khasnis SA, Kidiyoor KH, Patil AB, Kenganal SB. Vertical root fractures and their management. J Conserv Dent. 2014;17:103–10. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.128034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gluskin AH, Peters CI, Peters OA. Minimally invasive endodontics: Challenging prevailing paradigms. Br Dent J. 2014;216:347–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark D, Khademi JA. Case studies in modern molar endodontic access and directed dentin conservation. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:275–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ericson D. What is minimally invasive dentistry? Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2(Suppl 1):287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White JM, Eakle WS. Rationale and treatment approach in minimally invasive dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:13S–9S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark D, Khademi J, Herbranson E. Fracture resistant endodontic and restorative preparations. Dent Today. 2013;32:118. 120-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan K, Niu C, Xie Q, Jiang W, Gao L, Huang Z, et al. Comparative evaluation of the impact of minimally invasive preparation vs. Conventional straight-line preparation on tooth biomechanics: A finite element analysis. Eur J Oral Sci. 2016;124:591–6. doi: 10.1111/eos.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plotino G, Grande NM, Isufi A, Ioppolo P, Pedullà E, Bedini R, et al. Fracture strength of endodontically treated teeth with different access cavity designs. J Endod. 2017;43:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isufi A, Plotino G, Grande NM, Ioppolo P, Testarelli L, Bedini R, et al. Fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth restored with a bulkfill flowable material and a resin composite. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2016;7:4–10. doi: 10.11138/ads/2016.7.1.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monaco C, Arena A, Scotti R, Krejci I. Fracture strength of endodontically treated teeth restored with composite overlays with and without glass-fiber reinforcement. J Adhes Dent. 2016;18:143–9. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.a35908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharath Chandra SM, Agrawal N, Sujatha I, Sivaji K. Fracture resistance of endodontically treated single rooted premolars restored with sharonlay: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2016;19:270–3. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.181946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore B, Verdelis K, Kishen A, Dao T, Friedman S. Impacts of contracted endodontic cavities on instrumentation efficacy and biomechanical responses in maxillary molars. J Endod. 2016;42:1779–83. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Arx T, Chappuis V, Hänni S. Injuries to permanent teeth. Part 3: Therapy of root fractures. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2007;117:134–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishan R, Paqué F, Ossareh A, Kishen A, Dao T, Friedman S, et al. Impacts of conservative endodontic cavity on root canal instrumentation efficacy and resistance to fracture assessed in incisors, premolars, and molars. J Endod. 2014;40:1160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rundquist BD, Versluis A. How does canal taper affect root stresses? Int Endod J. 2006;39:226–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ElAyouti A, Serry MI, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Löst C. Influence of cusp coverage on the fracture resistance of premolars with endodontic access cavities. Int Endod J. 2011;44:543–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Freitas CR, Miranda MI, de Andrade MF, Flores VH, Vaz LG, Guimarães C, et al. Resistance to maxillary premolar fractures after restoration of class II preparations with resin composite or ceromer. Quintessence Int. 2002;33:589–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortega VL, Pegoraro LF, Conti PC, do Valle AL, Bonfante G. Evaluation of fracture resistance of endodontically treated maxillary premolars, restored with ceromer or heat-pressed ceramic inlays and fixed with dual-resin cements. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31:393–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasqualini D. Minimally invasive endodontics: A fancy trend or a clear road for the future? Int J Oral Dent Health. 2015;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunson M, Heilborn C, Johnson DJ, Cohenca N. Effect of apical preparation size and preparation taper on irrigant volume delivered by using negative pressure irrigation system. J Endod. 2010;36:721–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khademi A, Yazdizadeh M, Feizianfard M. Determination of the minimum instrumentation size for penetration of irrigants to the apical third of root canal systems. J Endod. 2006;32:417–20. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mincik J, Urban D, Timkova S, Urban R. Fracture resistance of endodontically treated maxillary premolars restored by various direct filling materials: An in vitro study. Int J Biomater. 2016;2016:9138945. doi: 10.1155/2016/9138945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]