Abstract

Lung contusion usually follows blunt trauma to the chest. If not properly diagnosed and adequately treated, it could at times be fatal as well. This case is being presented to highlight the radiological findings of this condition.

KEY WORDS: Contusion, lung, trauma

THE CASE

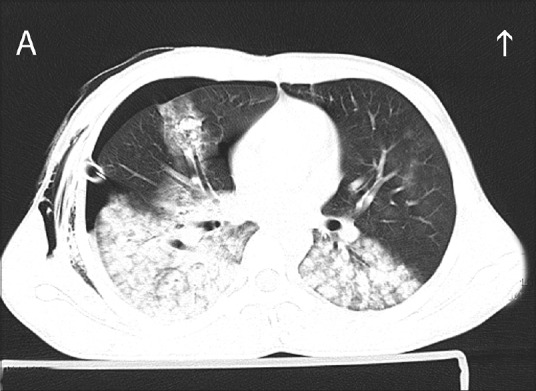

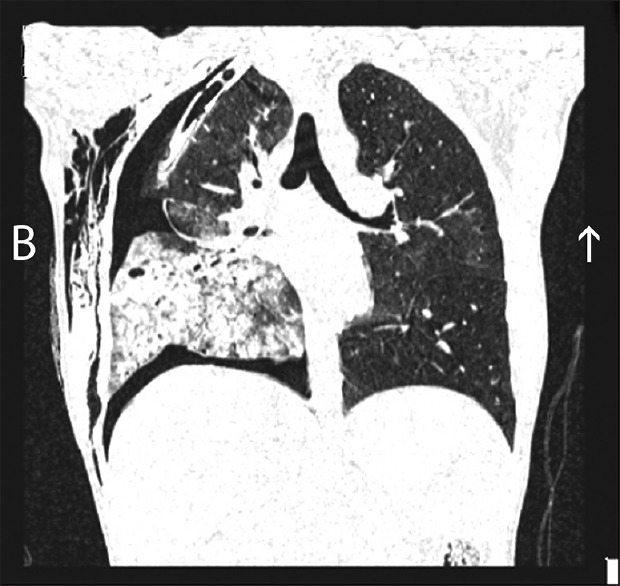

A 14-year-old boy was admitted in our hospital following a road traffic accident with multiple long bone fractures. Chest radiograph showed the presence of hemopneumothorax on the right side which was drained with an intercostal tube. Subsequently, a computerized tomogram (CT) of the chest was taken, which showed the presence of multiple alveolar space opacities with air bronchogram involving the right middle, right lower, left upper, and lower lobes [Figures 1 and 2]. Hemopneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema were also evident in the images. The findings are consistent with lung contusion. Figure 3 shows the three-dimensional volume rendering technology acquired in a 64-slice CT of the thorax in which incidentally, an undisplaced fracture of the ninth right rib laterally is also seen.

Figure 1.

Axial image of 64-slice computerized tomogram of the chest showing the presence of multiple nodular lesions with ill-defined margins and air bronchograms involving both lower lobes of lung. Pneumothorax and surgical emphysema on the right side and the intercostal drainage tube are also seen

Figure 2.

Coronal image of computed tomography thorax showing the presence of multiple nodular lesions with ill-defined margins and air bronchograms involving the right lower lobe. Pneumothorax and surgical emphysema on the same side and the intercostal drainage tube are also seen

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional volume rendering technology acquired in a 64-slice computerized tomogram of the thorax in which incidentally, an undisplaced fracture of the ninth right rib laterally is also seen

Lung contusion follows blunt trauma to the chest and the resulting injury to the alveolar capillaries causes accumulation of blood in the alveoli.[1] This interferes with gas exchange and produces hypoxia. The pathophysiological changes noted in this condition include ventilation – perfusion mismatch, intrapulmonary shunting, atelectasis, and loss of lung compliance.[2] Lung contusion is an independent risk factor for the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, and long-term respiratory dysfunction.[3,4] It also has a mortality rate of 10%–25%.[5] Usual CT scan findings include nonsegmental consolidation and ground glass opacities and this is a very sensitive tool to make a diagnosis of lung contusion.[6] Management is by supplemental oxygen and supportive measures including mechanical ventilation at times. Complete radiological clearance is mostly observed within 2 weeks.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ganie FA, Lone H, Lone GN, Wani ML, Singh S, Dar AM, et al. Lung contusion: A clinico-pathological entity with unpredictable clinical course. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2013;1:7–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppenheimer L, Craven KD, Forkert L, Wood LD. Pathophysiology of pulmonary contusion in dogs. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1979;47:718–28. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croce MA, Fabian TC, Davis KA, Gavin TJ. Early and late acute respiratory distress syndrome: Two distinct clinical entities. J Trauma. 1999;46:361–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonelli M, Moro ML, Capelli O, De Blasi RA, D'Errico RR, Conti G, et al. Risk factors for early onset pneumonia in trauma patients. Chest. 1994;105:224–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoff SJ, Shotts SD, Eddy VA, Morris JA., Jr Outcome of isolated pulmonary contusion in blunt trauma patients. Am Surg. 1994;60:138–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wylie J, Morrison GC, Nalk K, Kornecki A, Kotylak TB, Fraser DD, et al. Lung contusion in children – Early computed tomography versus radiography. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:643–7. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181a63f58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]