Abstract

Background:

The classification and treatment of patients who do not meet the criteria for a functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder has not been well established. This study aimed to record the prevalence of minor digestive symptoms (MDSs) in the general population attempting to divide them into symptom clusters as well as trying to assess their impact and the way sufferers cope with them.

Methods:

Following face-to-face interviews, a web-based, self-administered questionnaire was designed to capture a range of GI sensations using 34 questions and 12 images depicting abdominal symptoms. A randomly selected sample of 1515 women and 409 men representing the general population in France was studied. Cluster analysis was used to identify groups of respondents with naturally co-occurring symptoms. Data were also collected on other factors such as exacerbating and relieving strategies.

Results:

MDSs were reported at least every 2 months in 66.5% of women and 47.7% of men. A total of 11 symptom clusters were identified: constipation-like, flatulence, abdominal pressure, abdominal swelling, acid reflux, diarrhoea-like, intestinal heaviness, intestinal pain, gurgling, burning and gastric pain. Despite being minor, these problems had a major impact on vitality and self-image as well as emotional, social and physical well-being. Respondents considered lifestyle, food and disordered function as the main factors responsible for MDSs. Physical measures and dietary modification were the most frequent strategies adopted to obtain relief.

Conclusions:

MDSs are common and improved methods of recognition are needed so that better management strategies can be developed for individuals with these symptoms. The definition of symptom clusters may offer one way of achieving this goal.

Keywords: general population, imagery, minor digestive symptoms

Introduction

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are the subject of increasing interest and are defined as a combination of chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms with no clearly identifiable organic cause.1,2 In the case of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) these patients can suffer from moderate to severe pain or discomfort, an abnormal bowel habit, impaired health-related quality of life and disability.3,4 There is currently no specific objective biological or physiological marker for any of the FGIDs and, therefore, their identification and classification is based on symptom criteria. Different sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed to achieve a definition of these conditions, especially through clinical and epidemiological studies. The first attempt was made in the 1970s by Manning and colleagues5 and subsequently, successive working parties have defined Rome I6, Rome II7, Rome III8 and IV9 criteria. The Rome diagnostic criteria are now widely used and divide the FGIDs in adults into subcategories based on major anatomical domains: oesophageal, gastroduodenal disorders, bowel disorders, centrally mediated disorders of GI pain, gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorders, anorectal disorders, childhood functional GI disorders: neonate/toddler and childhood functional GI disorders: child/adolescent. In comparison to the Manning criteria, Rome I, II, III and IV criteria include the duration of symptoms in their definitions.

Numerous epidemiological studies have been performed to evaluate the prevalence of FGIDs or specific types of FGIDs such as IBS and functional dyspepsia. Results have shown large variations, mainly related to the use of different methodologies and diagnostic criteria, but also because there is considerable overlap between one FGID and another.10 Thus, the true prevalence of FGIDs remains unclear and controversial. However, all studies agree that FGIDs have a worldwide distribution and are very common, affecting a substantial proportion of individuals in the general population.

Many individuals experience a variety of mild GI symptoms from time to time, but they are difficult to classify as they do not conform to any of the currently available criteria such as those defined by the Rome Foundation. Consequently, these people cannot be offered a specific diagnosis and, therefore, for the purpose of this study, we have chosen to define them as minor digestive symptoms (MDSs). Since they are not captured by standard criteria, such as the Rome criteria, there is a lack of agreed language used to describe and characterize these complaints. FGIDs can have a major impact on the lives of patients but when symptoms are ‘minor’ or intermittent, a sufferer is less likely to consult a healthcare professional and rely more on self-management.2,11–13 It is, therefore, possible that individuals suffering from MDSs may not always receive optimal advice regarding prevention or management. Thus, a case could be made for the development of tools to better identify MDSs, which may then result in improved management strategies for these individuals. A fundamental aim in researching and treating any heterogeneous disorder is to subclassify the features into clusters able to predict optimal treatment strategies.14 Cluster analysis of patients’ symptoms has been performed in conditions such as functional constipation, IBS, cancer and gastroduodenal disorders.15–18 However, the evidence base for symptom-cluster analysis in different medical fields remains under debate17 and, therefore, particular attention to the development of better methodologies and cluster definitions is needed.

The management of FGIDs is facilitated by a range of interview skills and insights in order to interpret correctly symptoms that can be multiple and heterogeneous. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of factors in digestive disorders such as behaviour, underlying social mechanisms and perception.18 However, there appears to be a communication gap with respect to the description of sensations reported by the patient and the practitioner’s understanding and interpretation of the problem. For instance, the digestive system and the symptoms of FGIDs are linked to intimacy and marked by social norms, and symbolic and emotional values. As reported by Boltanski,19 knowledge of physiological function, as well as interest and attention that an individual pays to their body, physical sensations and representations differ from person to person and increases with social hierarchy. The strategies developed by individuals to cope with these disorders differ according to the representations of the body and the particular problem.18 Thus, MDSs cannot be assessed solely using a straightforward medical approach.

Consequently, there is a need to develop a multidimensional approach to the understanding of MDSs by integrating biological, social and psychological dimensions to depict, identify and understand more precisely these problems and their social and emotional consequences for individuals. Therefore, knowledge of these problems and an understandable phraseology that integrates individual levels of knowledge and imagery might complement existing medical knowledge.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the prevalence, impact and perceived causation of MDSs, in an attempt to identify specific clusters and corresponding management strategies used by individuals to overcome these problems. The survey was conducted through a structured questionnaire based on sensations perceived and described by individuals using words and imagery.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The survey was conducted by a market, opinion and social research company called Synovate SAS (Paris, France) (now part of Ipsos MORI), on 1515 randomly selected French women and 409 men, aged 18–70 years, suffering from MDSs. Participants were excluded if they had any noteworthy co-existent disease or a confirmed diagnosis of a functional GI disorder such as IBS. Representative subjects of the French population were selected from an internet database (Viewsnet) using quota sampling. Different criteria (e.g. age, educational level, geographical locality) were used for the selection of subjects.

Questionnaire

A preliminary qualitative survey was conducted among 20 French women by face-to-face interviews with psychologists. Subjects had to describe all digestive problems experienced during a 3-week period in a logbook using sentences and pictures. In addition, they were asked to list the social and emotional consequences and factors that appeared to precipitate their symptoms. The analysis of this survey enabled the development of a method to achieve a portrayal of MDSs, to establish a list of 34 different sensations or feelings (‘symptoms’) experienced by subjects and to select appropriate tools for the large-scale quantitative survey.

The quantitative approach was based on a questionnaire for assessing symptoms associated with MDSs. Subjects were invited to participate in the study via the Internet and completed the questionnaire online at home. The questionnaire was structured as follows. In the first part, subjects were asked to think about their digestive symptoms. They were then asked to describe what they perceived physically through a list of 34 symptoms using a scale of concern (0, not concerned; 1, concerned but not disturbing; 2, concerned and ranked a little disturbing; 3, concerned and ranked as rather disturbing; 4, concerned and ranked as the most disturbing). Subsequently, the subject was asked to focus on their most recent digestive problem and identify it from a list of previously defined symptoms and also relate how they felt about a series of 12 pictures developed to represent a variety of abdominal symptoms.20–21 Time and place of occurrence, severity, supposed trigger, social, emotional and physical consequences of the last problem experienced and management strategies adopted were also recorded. It should be noted that subjects who rated their digestive problems as severe were not permitted to continue with the survey.

Statistical analyses and clustering

A symptom was defined as a precise, one-dimensional sensation or fact, expressed through a description or a picture. An MDS was defined as a combination of symptoms that occurred at the same time.

The 34 different phrases that described an individual’s usual (most bothersome) problem and most recent digestive problem were ranked according to their frequency across the subjects. Pictures used to describe the most recent symptom were also ranked in order of frequency.

Standardized principal component analysis and ascending hierarchical clustering (with Ward’s method, data not shown) were used to gather subjects reporting similar combinations of symptoms. Subjects presenting with a similar profile of symptoms defined a particular cluster of an MDS. Data entry for clustering analysis was the response to the 34 digestive symptoms used to describe their most recent problem. Statistical analyses were performed using Daisy software designed by ADN Software (Medellin, Colombia).

On the basis of its most significant symptoms, each cluster received a definition related to the most representative symptom of the cluster.

Ethical Statement

Synovate is a company specializing in conducting consumer research and consent was obtained according to standard operating procedures. These operating procedures adhere to the European Society for Opinion and Market Research International Code of Conduct on Market, Opinion and Social Research, Data Analytics and Confidentiality, https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ICCESOMAR_Code_English_.pdf Consent was based on the following guidelines, https://www.esomar.org/uploads/public/knowledge-and-standards/codes-and-guidelines/ESOMAR_Guideline-for-online-research.pdf

Results

Participants

Among the 1515 women recruited, 1008 (66.5%) reported an MDS, abdominal discomfort or pain outside the time of menstruation, at least once every 2 months. Of these 1008 women, 985 (97.7%) completed the questionnaire and were considered for the analysis. 35.4% were aged 18–34 years, 44.7% were aged 35–54 years and 19.9% were aged 55–70 years. A total of 409 men were also recruited and 195 (47.7%) reported minor symptoms. As the male sample size was considerably smaller, abbreviated data on this group are presented where appropriate.

Occurrence of MDSs

MDSs occurred mainly during the summer (65% of women and men), to a lesser extent during winter (35%) and mainly during the week (88% and 90%). Symptoms occurred during the whole day (38% and 33%), in the evening (24% and 22%), the afternoon (21% and 22%), the morning (13% and 18%) and during sleep (4% and 5%), mainly at home (77% and 75%), outside their residence (33% and 34%) and at work (27% and 35%). On average, 5.6 types of symptoms (± 2.1) were reported.

Symptoms related to MDSs

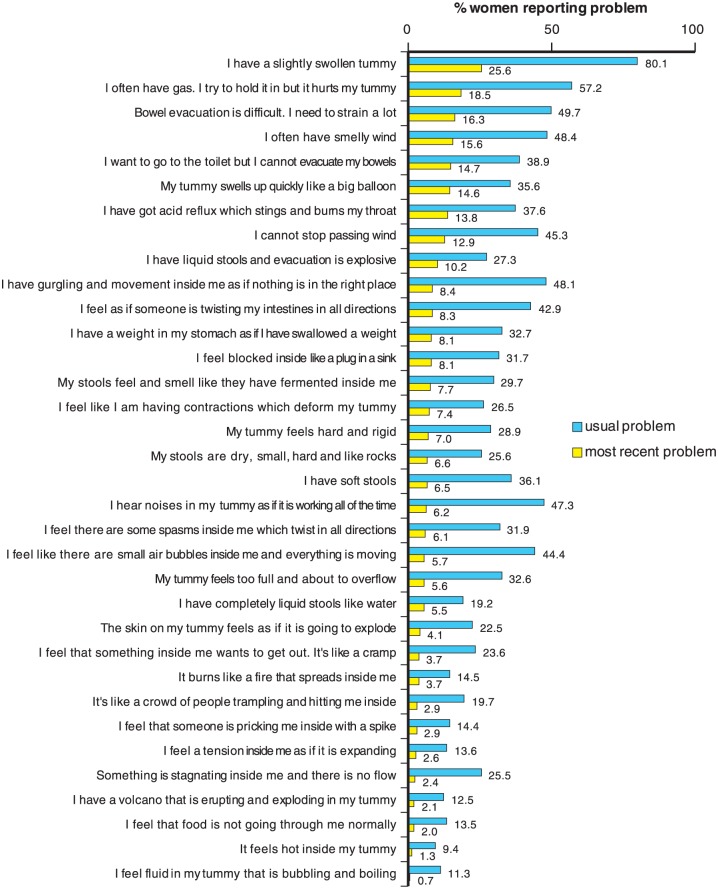

Figure 1 presents the main symptoms that described a particular MDS. The most frequent symptoms, reported by women as both usual and most recent, were related to abdominal swelling (80.1% ‘usual’ versus 25.6% ‘most recent’, respectively), pain due to gas (57.2% versus 18.5%), effort to evacuate (49.7% versus 16.3%) and smelly gas (48.4% versus 15.6%). There was a good correlation between the occurrence of the most recent and usual symptoms (y = 2.35x + 13.1; R2 = 0.7518; p < 0.05), suggesting that the most recent symptom was representative of the usual symptom (10% occurrence of the most recent symptom corresponded to 37% occurrence of the usual symptom).

Figure 1.

The main digestive symptoms experienced by women in terms of their usual gastrointestinal problem and their most recent problem. Results are expressed as a percentage of women experiencing the symptom.

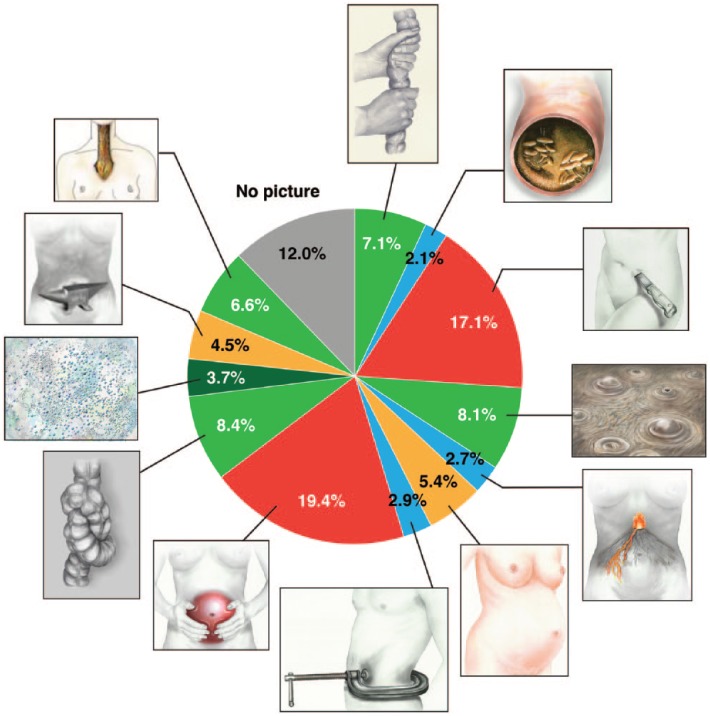

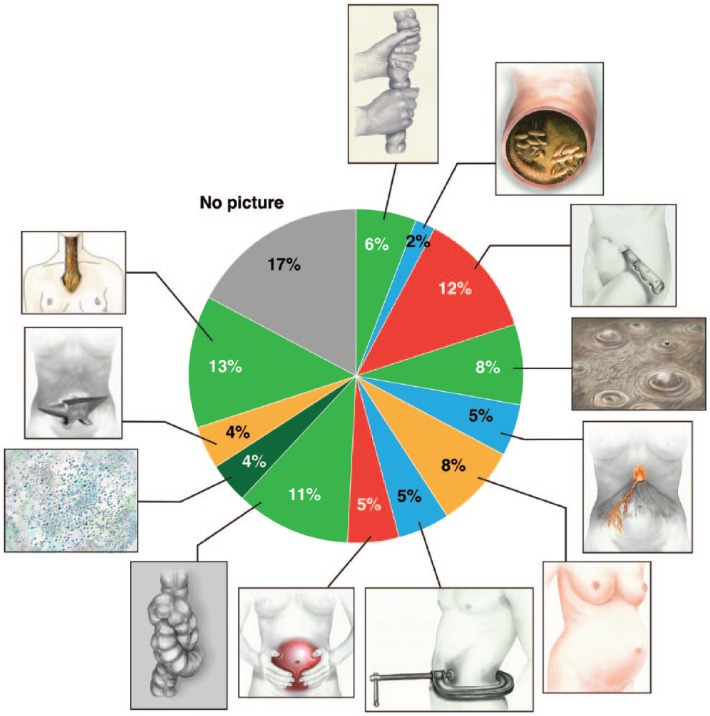

When participants were asked to relate their most recent digestive symptom to a picture, 88% of women (Figure 2) and 83% of men (Figure 3) selected one of the pictures shown in these two figures.

Figure 2.

The most recent gastrointestinal symptom described in women using pictures.

Figure 3.

The most recent gastrointestinal symptom described in men using pictures.

Impact of digestive symptoms and causation

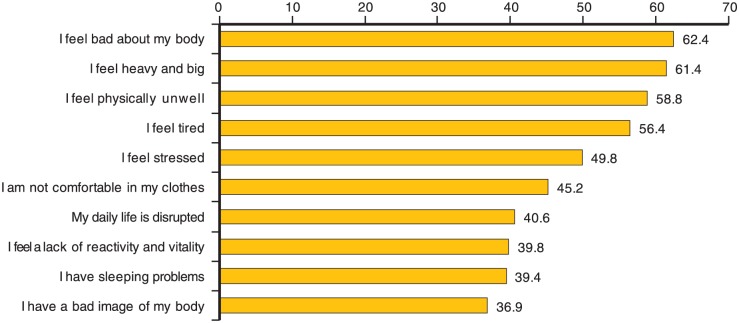

As shown in Figure 4, the most recent MDS had a strong emotional and social impact, mainly affecting physical conditions (90.5% of women) (feeling heavy or big, feeling physically ill, feeling stressed, uncomfortable in clothes, disturbed in daily life and sleeping problems), but also self-image (72.5%) (“I feel bad about my body”, “I have a bad image of my body”) and vitality (67.3%) (e.g. tiredness, lack of reactivity or vitality).

Figure 4.

Emotional and social impact of minor gastrointestinal disorders. The 10 most frequently reported effects are shown as the percentage of the whole population reporting that particular item.

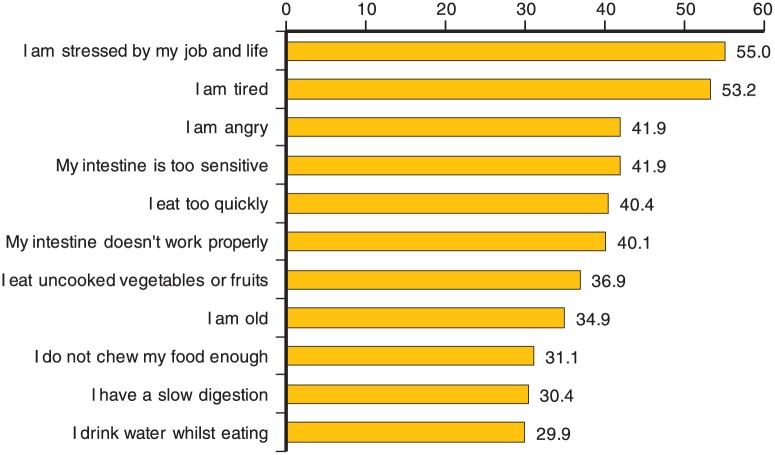

Figure 5 shows that causation was mainly linked to food type (73.6% of women) (uncooked vegetables or fruits, “I drink water whilst eating”), and food habits (53.5%) (“I eat too quickly”, “I do not chew my food enough”), but also physiology (75.5%) (“My intestine is too sensitive”, “My intestine doesn’t work properly”, “I am old”, “I have a slow digestion”), and lifestyle (77.0%) (stress, tiredness, anger).

Figure 5.

Perceived causation of minor gastrointestinal disorders. The 11 most frequently reported causes are shown as the percentage of the whole population reporting that particular item.

Identification of different clusters, impact and frequency

Amongst women, the combination of symptom phraseology and pictures of feelings resulted in the identification of 11 MDS clusters characterized by symptoms, time and place of occurrence, causation and impact (Tables 1 and 2): constipation-like (17.9%), flatulence (14.9%), abdominal pressure (11.4%), abdominal swelling (9.1%), acid reflux (8.5%), diarrhoea-like (8.4%), intestinal heaviness (7.6%), intestinal pain (5.9%), gurgling (5.3%), burning (5.2%) and gastric pain (2.4%). No specific cluster was identified for 3.4% of women. Although, several symptoms and pictures of feelings were common between clusters, each cluster highlighted very specific symptoms that were significantly more frequently reported in the cluster than in the whole population.

Table 1.

Characteristics of each of the symptom clusters. A cluster (e.g. constipation) is characterized by a specific combination of perceived symptoms expressed as the percentage of individuals reporting them in each cluster and in the total population. Symptoms that are highlighted in different colours are significantly higher in the cluster than in the whole population (significance set at p < 0.05).

| Symptom | Constipation | Intestinal heaviness | Abdominal pressure | Swollen tummy | Intestinal pain | Gurgling | Flatulence | Diarrhoea | Gastric pain | Acid reflux | Burning | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burning sensations | ||||||||||||

| Acid reflux which stings and burns my throat. | 2.8 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 33.3 | 100 | 27.5 | 13.8 |

| It feels hot inside my tummy. | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.3 |

| It burns like a fire that spreads inside me. | 0.6 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 52.9 | 3.7 |

| Fullness sensations | ||||||||||||

| My tummy feels too full and about to overflow. | 5.7 | 25.3 | 8.0 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 5.6 |

| I have a weight in my stomach as if I have swallowed a weight. | 3.4 | 52.0 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 3.6 | 12.5 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 8.1 |

| Tummy texture and volume | ||||||||||||

| I have a slightly swollen tummy. | 22.7 | 18.7 | 18.8 | 78.9 | 17.2 | 28.8 | 23.8 | 12.0 | 20.8 | 11.9 | 19.6 | 25.6 |

| My tummy feels hard and rigid. | 9.1 | 5.3 | 25.0 | 6.7 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 3.9 | 7.0 |

| My tummy swells up quickly like a balloon. | 7.4 | 18.7 | 65.2 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 5.8 | 8.2 | 12.0 | 4.2 | 6.0 | 5.9 | 14.6 |

| The skin of my tummy feels as if it is going to explode. | 1.7 | 6.7 | 17.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 4.1 |

| Blockage sensations | ||||||||||||

| I feel blocked inside like a plug in the sink. | 29.0 | 4.0 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 9.8 | 8.1 |

| Something is stagnating inside me and there is no flow. | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 2.4 |

| I feel that food is not going through me normally. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 58.3 | 1.2 | 5.9 | 2.0 |

| Internal movements | ||||||||||||

| I have gurgling and movement inside me as if nothing is in the right place. | 6.3 | 8.0 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 8.6 | 50.0 | 6.8 | 6.0 | 8.3 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 8.4 |

| I hear noises in my tummy as if it is working all the time. | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 5.2 | 55.8 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 8.3 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 6.2 |

| I feel like there are small air bubbles inside me and everything is moving. | 2.3 | 2.7 | 24.1 | 1.1 | 10.3 | 5.8 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 5.7 |

| It’s like a crowd of people trampling and hitting me inside. | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 30.8 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| I have a volcano that is erupting and exploding in my tummy. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 23.5 | 2.1 |

| I feel fluid in my tummy that is bubbling and boiling. | 0.0 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| Internal pain and tensions | ||||||||||||

| I feel I am having contractions which deform my tummy. | 1.7 | 0.0 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 65.5 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 7.8 | 7.4 |

| I feel as if someone is twisting my intestines in all directions. | 1.7 | 41.3 | 6.3 | 1.1 | 13.8 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 16.7 | 3.6 | 7.8 | 8.3 |

| I feel that something inside me wants to get out. It’s like a cramp. | 2.3 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 3.7 |

| I feel there are some spasms inside me which twist in all directions. | 1.1 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 53.4 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 20.8 | 1.2 | 9.8 | 6.1 |

| I feel a tension inside me as if it is expanding. | 0.6 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 54.2 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 2.6 |

| I feel that someone is pricking me inside with a spike. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 45.1 | 2.9 |

| Gas | ||||||||||||

| I often have gas. I try to hold it in but it hurts my tummy. | 14.2 | 6.7 | 23.2 | 4.4 | 10.3 | 13.5 | 54.4 | 14.5 | 4.2 | 6.0 | 9.8 | 18.5 |

| I often have smelly wind. | 13.6 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 2.2 | 10.3 | 0.0 | 57.1 | 20.5 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 9.8 | 15.6 |

| I cannot stop passing wind. | 5.7 | 1.3 | 7.1 | 1.1 | 5.2 | 13.5 | 47.6 | 15.7 | 16.7 | 4.8 | 9.8 | 12.9 |

| Stool | ||||||||||||

| My stools are dry, small, hard and like rocks. | 22.2 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 6.8 | 1.2 | 8.3 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 6.6 |

| My stools feel and smell like they have fermented inside me. | 5.1 | 1.3 | 8.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 12.2 | 34.9 | 8.3 | 0.0 | 7.8 | 7.7 |

| I have liquid stools and evacuation is explosive. | 1.7 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 0.0 | 15.5 | 9.6 | 4.8 | 67.5 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 9.8 | 10.2 |

| I have soft stools. | 0.0 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 24.4 | 6.9 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 12.0 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 9.8 | 6.5 |

| I have completely liquid stools like water. | 0.0 | 5.3 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 13.8 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 33.7 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 9.8 | 5.5 |

| Evacuation | ||||||||||||

| I want to go to the toilet but I cannot evacuate my bowels. | 55.7 | 4.0 | 11.6 | 2.2 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 6.1 | 3.6 | 12.5 | 3.6 | 9.8 | 14.7 |

| Bowel evacuation is difficult. I need to strain a lot. | 53.4 | 6.7 | 15.2 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 11.5 | 12.2 | 6.0 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 7.8 | 16.3 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of each cluster in terms of prevalence, main symptoms, when and where they occur, their cause and their impact on the individual.

| Cluster | Prevalence | Main symptoms | Occurrence | Cause | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constipation | 17.9% | Blocked sensation, dry, small and hard stools, difficult defecation. | At home, during the day. | Physiological: intestinal dysfunction, slow digestion. Lifestyle: delayed defecation as not at home. |

Image: feeling heavy and big. Physical condition: afraid of blocked bowel. |

| Intestinal heaviness | 7.6% | Fullness sensation, full tummy, weight in the tummy, pain, twisted intestines. | Evening. | Physiological: intestinal dysfunction, slow digestion. Lifestyle: stress, during periods. Food habits: eat too quickly, eat too much. |

Image: feeling heavy and big, I feel bad about my body. Physical condition: tired, loss of energy, lack of well-being. Social life: frustration as cannot eat what I want. Worried about my appearance. |

| Abdominal pressure | 11.4% | Tummy enlarged, hard, rigid wall, tight skin, air bubbles, internal tension, something expanding inside me. | Work place, during the day. | Physiological: intestinal dysfunction, slow digestion. Food habits: eating too much, fatty foods, fruit and vegetables. |

Image: feeling heavy and big, feel bad about my body, concern about appearance. Physical condition: backache, work, stress, clothes do not fit, feeling unwell. Social life: social relationship and sex life disturbed. Vitality: lack of vitality and energy. |

| Swollen tummy | 9.1% | Swollen tummy, like a big balloon, tummy feels it is going to explode, something expanding inside me. | Evening. | Physiological: during periods, tired. Food habits: vegetables, spicy food, cereals, do not chew enough. |

Image: like a balloon. Physical condition: feeling uncomfortable in clothes. |

| Intestinal pain | 5.9% | Pain, contractions, twisting and stretching. | Night and morning. | Physiological: intestine too sensitive. Food habits: alcohol. |

Physical condition: backache, intestinal movement, difficult to work, difficult to concentrate, uncomfortable in clothes. Vitality: bad mood, helpless. |

| Gurgling | 5.3% | Internal movements and gurgling. | Afternoon and evening. | Food habits: coffee, uncooked vegetables, spicy food, too much food, eating too quickly. Lifestyle: tired. |

Image: feeling unwell. Physical condition: disturbed at work. Social life: not at ease in surroundings. |

| Flatulence | 14.9% | Frequent gas, smelly wind, cannot stop passing wind, fermented stools. | Out of home. | Food habits: uncooked vegetables, fruits, spicy food, cereals, soft drinks, vegetables, alcohol, eating too quickly, insufficient chewing, food in excess. Lifestyle: hold it in because not at home. |

Image: feeling dirty. Physical condition: bad breath, losing control, disturbed at work. Social life: not at ease in surroundings, social relationships disturbed, need isolation, concern about appearance. |

| Diarrhoea | 8.4% | Loose or watery stools, explosive defecation, fermented stools. | During summer, at home, in the morning. | Food habits: uncooked vegetables or fruits, soft drinks, cereals. Physiological: intestine too sensitive, intestinal dysfunction. |

Physical condition: bad breath, disturbed at work, interference with daily life. Social life: need of isolation, sensation of losing control of situation, not at ease in surroundings, social relationships and sex life disturbed. Vitality: feeling helpless. |

| Gastric pain | 2.4% | Expanding and tearing tension inside, contractions. | Night and morning. | Physiological: intestinal dysfunction. |

Image: feeling dirty. Physical condition: feel unwell, backache and headache, sleeping badly. Social life: need isolation, loss of control, not at ease with surroundings, worse with food consumption, social relationships and sex life disturbed. Vitality: bad mood, feeling helpless. |

| Acid reflux | 8.5% | Burning sensations in the throat, acid reflux. | At home, during sleep. |

Physiological: slow digestion. Food habits: fatty food, spicy food, too much coffee, soft drinks, alcohol, eating too quickly. Lifestyle: being stressed. |

Physical condition: sleeping problems, bad breath. Social life: frustration about food. |

| Burning | 5.2% | Burning sensations, a volcano in my tummy, hot in tummy, fire inside me. | Workplace. |

Physiological: intestine too sensitive. Lifestyle: being stressed. Food habits: coffee, soft drinks. |

Physical condition: Disturbance of daily life, difficulties in concentration, poor sleep. Social life: frustration about food, not at ease with surroundings, difficult social relationships. Vitality: lack of vitality, feeling helpless. |

Clustering showed that gurgling and burning were more likely to occur amongst younger women (< 34 years), while flatulence and intestinal heaviness were more of an issue for older women (> 55 years).

Some clusters reported by a large proportion of women and which occur frequently (daily to weekly), may be painful, such as gastric pain, or, in contrast, have a low impact on pain or well-being, such as flatulence (Table 3).

Table 3.

Impact and frequency of the most recent minor digestive symptoms. The impact is illustrated by the percentage of women in each cluster declaring that the symptom had a significant impact on their life or was painful. The frequency, low or high, is shown as the percentage of women in each cluster experiencing the symptom at least on a weekly basis.

| Digestive problem | Proportion (%) impacted by symptom | Proportion (%) reporting symptom as at least once a week |

|---|---|---|

| Constipation | 71.6 | 40.9 |

| Intestinal heaviness | 77.3 | 33.3 |

| Abdominal pressure | 81.3 | 44.6 |

| Tummy swelling | 44.4 | 30.0 |

| Intestinal pain | 77.6 | 27.6 |

| Gurgling | 65.4 | 38.5 |

| Flatulence | 67.3 | 52.4 |

| Diarrhoea | 78.3 | 41.0 |

| Gastric pain | 91.7 | 54.2 |

| Acid reflux | 63.1 | 41.7 |

| Burning | 76.5 | 49.0 |

The different clusters identified in men were: flatulence (23.1%), acid reflux (16.4%), diarrhoea-like (14.9%), constipation-like (10.3%), abdominal swelling (7.7%), abdominal pressure (6.2%), gurgling (5.1%), intestinal heaviness (4.6%), burning (4.6%), intestinal pain (2.1%) and gastric pain (1.5%). No specific cluster was identified for 3.5% of men.

Preventive and treatment strategies

No major differences were observed between clusters in terms of their preventive strategies (Table 4). Food habits, specific food use and food avoidance remained the first strategy in all clusters and were used by 61–100% of women. Physical activity was chosen by 17–47% of women and some form of medication was used as a preventive strategy in 4–20% of women, but very few of them (2.2%) had no preventive strategy at all.

Table 4.

Preventive strategies adopted by people in each cluster. Results are expressed as the percentage of women selecting a given strategy in each cluster and in the whole female population. Items that are highlighted with different colours are significantly higher in the cluster than in the whole population (significance set at p < 0.05).

| Constipation | Intestinal heaviness | Abdominal pressure | Tummy swelling | Intestinal pain | Gurgling | Flatulence | Diarrhoea | Gastric pain | Acid reflux | Burning | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | 4.0 | 4.0 | 11.6 | 8.9 | 13.8 | 7.7 | 12.2 | 8.4 | 20.8 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 8.7 |

| I take active charcoal | 4.0 | 4.0 | 11.6 | 8.9 | 13.8 | 7.7 | 12.2 | 8.4 | 20.8 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 8.7 |

| Food habits | 93.8 | 98.7 | 93.8 | 96.7 | 86.2 | 92.3 | 91.2 | 91.6 | 95.8 | 95.2 | 96.1 | 93.8 |

| I chew well | 51.1 | 61.3 | 53.6 | 56.7 | 63.8 | 71.2 | 46.9 | 45.8 | 54.2 | 59.5 | 60.8 | 55.1 |

| I eat slowly | 38.6 | 48.0 | 43.8 | 45.6 | 37.9 | 59.6 | 36.1 | 42.2 | 50.0 | 47.6 | 37.3 | 42.6 |

| I avoid heavy meals | 67.6 | 76.0 | 71.4 | 74.4 | 51.7 | 71.2 | 65.3 | 66.3 | 70.8 | 72.6 | 56.9 | 67.9 |

| I avoid drinking water during meals | 27.8 | 34.7 | 32.1 | 26.7 | 24.1 | 28.8 | 30.6 | 16.9 | 37.5 | 21.4 | 21.6 | 27.2 |

| I drink a glass of water when I awaken | 34.1 | 24.0 | 25.0 | 27.8 | 17.2 | 32.7 | 27.9 | 24.1 | 29.2 | 27.4 | 19.6 | 27.2 |

| I make myself have regular meal times | 45.5 | 53.3 | 53.6 | 51.1 | 51.7 | 57.7 | 44.9 | 38.6 | 45.8 | 47.6 | 43.1 | 48.1 |

| I have a light diet | 59.1 | 68.0 | 60.7 | 63.3 | 50.0 | 73.1 | 59.2 | 53.0 | 45.8 | 60.7 | 66.7 | 59.9 |

| I have a balanced diet | 68.8 | 81.3 | 70.5 | 75.6 | 60.3 | 76.9 | 65.3 | 57.8 | 70.8 | 67.9 | 70.6 | 69.3 |

| Food prescription | 94.3 | 96.0 | 99.1 | 96.7 | 91.4 | 100.0 | 94.6 | 96.4 | 95.8 | 94.0 | 92.2 | 95.6 |

| I drink a lot of water | 64.2 | 66.7 | 64.3 | 65.6 | 60.3 | 71.2 | 64.6 | 65.1 | 54.2 | 63.1 | 60.8 | 64.2 |

| I eat vegetables | 86.4 | 88.0 | 83.0 | 87.8 | 86.2 | 92.3 | 85.0 | 77.1 | 95.8 | 84.5 | 78.4 | 85.5 |

| I eat bifidobacteria yoghurts daily | 22.2 | 17.3 | 30.4 | 17.8 | 12.1 | 13.5 | 17.7 | 13.3 | 16.7 | 14.3 | 17.6 | 18.7 |

| I cook all vegetables | 9.1 | 14.7 | 18.8 | 10.0 | 15.5 | 15.4 | 17.0 | 16.9 | 29.2 | 20.2 | 23.5 | 15.5 |

| I eat any yoghurt daily | 62.5 | 61.3 | 62.5 | 56.7 | 56.9 | 65.4 | 64.6 | 50.6 | 66.7 | 64.3 | 58.8 | 61.0 |

| I eat food containing fibre | 75.6 | 68.0 | 67.0 | 66.7 | 53.4 | 63.5 | 68.0 | 61.4 | 62.5 | 66.7 | 54.9 | 66.7 |

| I eat starchy food | 68.2 | 72.0 | 69.6 | 76.7 | 70.7 | 76.9 | 68.0 | 81.9 | 83.3 | 73.8 | 66.7 | 72.2 |

| Food prohibition | 75.6 | 81.3 | 80.4 | 75.6 | 74.1 | 88.5 | 74.1 | 74.7 | 83.3 | 81.0 | 60.8 | 77.1 |

| I avoid dairy products | 9.1 | 20.0 | 13.4 | 17.8 | 15.5 | 13.5 | 15.6 | 10.8 | 25.0 | 8.3 | 11.8 | 14.0 |

| I avoid uncooked vegetables | 3.4 | 22.7 | 20.5 | 8.9 | 22.4 | 15.4 | 13.6 | 18.1 | 12.5 | 14.3 | 21.6 | 14.2 |

| I avoid soft drinks | 50.6 | 56.0 | 53.6 | 44.4 | 41.4 | 51.9 | 49.0 | 37.3 | 58.3 | 56.0 | 41.2 | 49.2 |

| I avoid fatty foods | 57.4 | 64.0 | 64.3 | 61.1 | 55.2 | 73.1 | 59.2 | 57.8 | 50.0 | 58.3 | 43.1 | 59.3 |

| Sport | 34.1 | 44.0 | 37.5 | 44.4 | 31.0 | 34.6 | 42.9 | 20.5 | 16.7 | 21.4 | 47.1 | 35.1 |

| I exercise regularly | 34.1 | 44.0 | 37.5 | 44.4 | 31.0 | 34.6 | 42.9 | 20.5 | 16.7 | 21.4 | 47.1 | 35.1 |

| Nothing | 3.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 6.9 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 2.2 |

Treatment strategies were much more variable from one cluster to another (Table 5). Around 45–77% of women used water and food (food with fibres, yogurt, fruit) and 68–100% used physical measures (massage or rubbing of the abdomen, lying down, breathing correctly) as treatment strategies. Around 30–67% used medication and 36–55% relaxation. No treatment was used by 8.7% women (0–18% depending on the cluster). Women suffering from constipation-like symptoms used mainly food (77.3%) as a treatment, whereas of women suffering from acid reflux or burning used mainly medication (66.7% and 54.9%, respectively).

Table 5.

Treatment strategies adopted by people in each cluster. Results are expressed as the percentage of women selecting a given strategy in each cluster and in the whole female population. Items that are highlighted with different colours are significantly higher in the cluster than in the whole population (significance set at p < 0.05).

| Constipation | Intestinal heaviness | Abdominal pressure | Tummy swelling | Intestinal pain | Gurgling | Flatulence | Diarrhoea | Gastric pain | Acid reflux | Burning | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body management | 73.9 | 86.7 | 87.5 | 75.6 | 91.4 | 82.7 | 76.2 | 67.5 | 100.0 | 69.0 | 84.3 | 79.0 |

| I massaged my tummy | 44.3 | 45.3 | 58.0 | 44.4 | 51.7 | 51.9 | 36.7 | 33.7 | 58.3 | 26.2 | 52.9 | 44.4 |

| I lay down | 37.5 | 45.3 | 44.6 | 30.0 | 51.7 | 40.4 | 36.1 | 42.2 | 54.2 | 42.9 | 47.1 | 41.3 |

| I tried to breath correctly | 27.8 | 38.7 | 28.6 | 24.4 | 43.1 | 34.6 | 29.3 | 30.1 | 54.2 | 33.3 | 37.3 | 32.3 |

| I rubbed my tummy | 23.3 | 42.7 | 25.9 | 21.1 | 31.0 | 34.6 | 27.9 | 13.3 | 37.5 | 27.4 | 31.4 | 27.2 |

| I went without food | 9.7 | 29.3 | 18.8 | 13.3 | 15.5 | 23.1 | 10.9 | 21.7 | 25.0 | 9.5 | 19.6 | 15.8 |

| I exercised | 10.8 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 18.9 | 6.9 | 11.5 | 15.6 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 7.8 | 10.4 |

| I warmed my tummy | 9.7 | 9.3 | 15.2 | 8.9 | 13.8 | 17.3 | 7.5 | 4.8 | 25.0 | 9.5 | 15.7 | 11.1 |

| I tapped on my chest | 1.7 | 1.3 | 5.4 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 8.3 | 1.2 | 7.8 | 2.6 | |

| I walked | 25.6 | 28.0 | 32.1 | 31.1 | 17.2 | 32.7 | 32.7 | 16.9 | 37.5 | 20.2 | 23.5 | 27.0 |

| I undressed | 27.3 | 29.3 | 29.5 | 25.6 | 17.2 | 28.8 | 21.1 | 25.3 | 33.3 | 21.4 | 27.5 | 25.7 |

| I lay down on my tummy | 17.6 | 17.3 | 17.9 | 13.3 | 25.9 | 17.3 | 18.4 | 18.1 | 25.0 | 22.6 | 21.6 | 18.9 |

| I forced myself to vomit | 2.8 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 2.2 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 3.5 |

| I used an enema | 4.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.9 | ||||

| Drug | 48.9 | 40.0 | 42.9 | 30.0 | 60.3 | 32.7 | 42.2 | 38.6 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 54.9 | 46.0 |

| I took a drug | 35.8 | 38.7 | 31.3 | 17.8 | 55.2 | 25.0 | 29.3 | 36.1 | 62.5 | 63.1 | 52.9 | 37.4 |

| I took active charcoal | 6.3 | 5.3 | 12.5 | 8.9 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 14.3 | 6.0 | 12.5 | 3.6 | 8.6 | |

| I used a glycerin suppository | 15.9 | 4.0 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 1.9 | 5.4 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 5.8 | |||

| I ate yeast | 3.4 | 2.7 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 1.9 | 5.4 | 10.8 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 5.1 |

| I ate a fibre preparation | 9.7 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 2.2 | 5.2 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 4.2 | |

| Food | 77.3 | 68.0 | 71.4 | 66.7 | 44.8 | 75.0 | 67.3 | 62.7 | 62.5 | 66.7 | 64.7 | 67.9 |

| I drank water | 50.0 | 45.3 | 50.9 | 41.1 | 31.0 | 46.2 | 40.1 | 45.8 | 29.2 | 45.2 | 41.2 | 44.3 |

| I ate foods with fibre | 42.0 | 16.0 | 24.1 | 25.6 | 10.3 | 15.4 | 17.0 | 10.8 | 20.8 | 7.1 | 21.6 | 21.7 |

| I ate a yoghurt | 25.0 | 17.3 | 17.9 | 21.1 | 17.2 | 23.1 | 19.7 | 14.5 | 8.3 | 14.3 | 21.6 | 19.0 |

| I ate a bifidobacteria yoghurt | 29.0 | 20.0 | 26.8 | 17.8 | 15.5 | 11.5 | 21.1 | 8.4 | 12.5 | 10.7 | 13.7 | 19.2 |

| I ate a fruit | 36.9 | 12.0 | 14.3 | 15.6 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 7.2 | 9.5 | 15.7 | 16.0 | |

| I drank a soft drink | 11.4 | 13.3 | 12.5 | 11.1 | 15.5 | 13.5 | 17.0 | 21.7 | 16.7 | 15.5 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| I drank tea/infusion | 31.3 | 34.7 | 31.3 | 26.7 | 12.1 | 34.6 | 31.3 | 18.1 | 33.3 | 17.9 | 27.5 | 27.8 |

| I drank a squeezed lemon | 8.0 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 1.2 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 6.0 |

| Relaxing | 42.6 | 52.0 | 40.2 | 37.8 | 36.2 | 51.9 | 40.8 | 38.6 | 45.8 | 41.7 | 54.9 | 43.2 |

| I tried to relax (reading, music, etc.) | 39.8 | 50.7 | 37.5 | 36.7 | 32.8 | 44.2 | 38.1 | 33.7 | 41.7 | 40.5 | 49.0 | 40.3 |

| I took a bath | 6.3 | 5.3 | 4.5 | 6.7 | 3.4 | 13.5 | 4.1 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 4.8 | 13.7 | 6.7 |

| Nothing | 5.7 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 12.2 | 3.4 | 9.6 | 12.9 | 18.1 | 7.1 | 2.0 | 8.6 |

Discussion

This survey showed that 66.5% of French women suffered from MDSs at least once every 2 months with the proportion of men experiencing these symptoms lower (48%), although the male sample was considerably smaller. The most frequent symptoms in women were related to abdominal swelling (80.1%), pain due to gas (57.2%), difficulties with evacuation (49.7%), offensive gas (48.4%) and burning (37.6%). These findings are broadly consistent with previous population-based surveys either looking at functional GI symptoms in general or using diagnostic criteria to apply a specific functional GI diagnosis to participants.11,22,23

Our cluster analysis identified 11 groups of subjects with naturally co-occurring GI symptoms. Each cluster received a name with the most common in women being constipation-like (17.9%), flatulence (14.9%), abdominal pressure (11.4%) and abdominal swelling (9.1%). In men, the most frequent clusters were flatulence (23.1%), acid reflux (16.4%), diarrhoea-like (14.9%) and constipation-like (10.3%) symptoms. The main differences between men and women were observed for flatulence (23.1% versus 14.9%, respectively), acid reflux (16.4% versus 8.5%), constipation-like (10.3% versus 17.9%), diarrhoea-like (14.9% versus 8.4%) and abdominal pressure (6.2% versus 11.4%). It should be noted that a symptom might be common to different clusters, for example, a slightly swollen abdomen is mentioned to a variable extent in most of the clusters. However, there is frequently an overlap of symptoms between different FGIDs, such as functional constipation and constipation-predominant IBS and even more apparently distinct conditions such as functional dyspepsia and IBS can overlap symptomatically in a number of different ways.2 MDSs appear to be no exception to this rule and, therefore, make management rather challenging.

FGIDs are important in terms of public health because they are frequent, can be disabling and are associated with major social, quality of life and economic burdens.10–12,23–25 In particular, IBS and functional dyspepsia have a large impact on absenteeism, work productivity and healthcare expenditure.3,11,12,26 Our survey shows that even MDSs are associated with a significant emotional and social impact as well as affecting physical well-being, self-image and vitality. The impact was related to the type of digestive problem with abdominal pain having the strongest effect. There is evidence that quality of life can be improved by treating FGIDs, especially functional dyspepsia and IBS,25,27 and it is likely that MDSs would behave in the same way. Our survey showed that physical measures and dietary manipulation were the most frequent strategies adopted by subjects in order to try and relieve their symptoms. Interestingly, relaxation was also mentioned, which is consistent with the fact that stress is reported as an important trigger in many of these problems. Cluster analysis showed that subjects adopted specific strategies for different problems, such as the manipulation of dietary fibre as well as the consumption of fruit or yogurt for constipation and activated charcoal for flatulence, although these do not necessarily have a firm evidence base. It seems likely that patients with FGIDs adopt similar strategies and, for instance, it has been reported that diet and food choice are often dictated by current IBS symptoms.12

Some key parameters must be taken into account when designing surveys such as this one, as methods of recruitment, sample characteristics, content of survey questions, the modality used to collect information and the way the analyses are undertaken can all affect the results. Clinic-based surveys refer to data collected in the in- and out-patient setting and are useful for assessing the epidemiology of subjects requiring medical care.2 However, such surveys are unlikely to be representative of the general population, due to the characteristics of those seeking medical care for reasons such as symptom severity, concerns about the nature of their symptoms and ease of access to care. Since many people with FGIDs do not seek medical care, population-based surveys are more relevant for assessing the prevalence of FGIDs in the community.2 In population-based surveys, no medical evaluation is performed to exclude structural diagnosis, thus the occurrence of FGIDs may be overestimated.2 However, in our study, subjects reporting severe FGID-type symptoms were excluded and, consequently, the sample obtained should have been reasonably representative of the French general population. Data can be collected by telephone, face-to-face interviews or self-administered questionnaires distributed by mail or online. For this study, we chose a self-administered questionnaire delivered by e-mail (web survey) for the following reasons. The answers of the participants could not be influenced by the interviewer and information could be collected from a variety of locations in a large number of respondents, which increases the power of the statistical analysis. Furthermore, the convenience of completing the survey anonymously in the privacy of the home encouraged more truthful answers. Web-based surveys do have the disadvantage that there is the potential for respondents to misunderstand questions or the terms being used, but this risk was minimized by the use of items that were easy to understand and derived from patients as well as the use of pictures to facilitate communication.

The 34 symptoms listed in our questionnaire were not related to the Manning or Rome criteria, but were derived from sensations and perceptions described by the subjects themselves in their own words. In addition, an imagery-type approach developed by Carruthers and colleagues20,21 for subjects suffering from IBS was used to allow the subjects to express their symptoms in a nonverbal way. Interestingly, the response to imagery followed a rather similar pattern suggesting that imagery may be a useful way of capturing symptoms in different populations.

This survey was undertaken during the summer in a French population and it would be interesting to repeat it during another season and in another country, to establish whether these clusters are stable during the whole year and in different geographical locations. An unexpected finding was that symptoms appeared to be worse when participants were at home rather than at work, which initially may seem the opposite of what might be anticipated. However, it could be that whilst at work individuals are distracted from their symptoms and this suggests that sufferers should be possibly discouraged from staying at home when symptomatic. Patients with FGIDs are notorious for their absenteeism from work and this latter finding suggests that encouraging such individuals to stay at work, even when suffering from symptoms, should form part of their management strategy.

Diagnostic criteria such as those developed by the Rome Foundation have utility in defining those conditions seen in the medical setting, but our results show that there is a large population of individuals suffering from GI symptoms that currently cannot be classified by the use of these criteria. It is unlikely that it will ever be possible to apply a specific diagnosis to individuals suffering from these minor symptoms and, in fact, it could be disadvantageous to ‘medicalize’ these problems too much. However, this does not mean they should be ignored as this study clearly shows that people with MDSs need help with the management of these problems. This might be achieved by developing treatment strategies for the specific clusters identified in this study, which is likely to be dependent on the symptom profile of the particular cluster. Consequently, further research trying to identify effective management strategies for the various clusters should help these individuals, who are not consulting the medical profession, to better self-manage their symptoms. Such information might also be particularly useful for pharmacists who are often consulted by these people when they need advice.

Acknowledgments

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study as well as the analysis and interpretation of the data. SL-R, HRC and PJW drafted the article and all authors approved the final version.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by Danone Nutricia Research.

Conflict of interest statement: DL’H-B and SL-R are employees of Danone Nutricia Research. Over the last 5 years PJW has acted as a consultant for, or received research grant support from, the following pharmaceutical companies: Almirall Pharma, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chr. Hansen, Danone Nutricia Research, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Salix, Shire UK, Sucampo Pharmaceuticals and Allergan.

Contributor Information

Diane L’Heureux-Bouron, Danone Nutricia Research, Palaiseau, France.

Sophie Legrain-Raspaud, Danone Nutricia Research, Palaiseau, France.

Helen R. Carruthers, Education and Research Centre, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester, M23 9LT, UK

P. J. Whorwell, Centre for Gastrointestinal Sciences, University of Manchester, Wythenshawe Hospital, M23 9LT, UK.

References

- 1. Tanaka Y, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S, et al. Biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17: 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corazziari E. Definition and epidemiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 18: 613–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 40: 1023–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Longstreth GF, Drossman DA. Severe irritable bowel and functional abdominal pain syndromes: managing the patient and health care costs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3: 397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, et al. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. Br Med J 1978; 2: 653–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Drossman DA, Richter JE, Talley NJ, et al. (eds). The functional gastrointestinal disorders: diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ, et al. Rome II: a multinational consensus document on functional gastrointestinal disorders? Gut 1999; 45(Suppl. II): 1–81.10369691 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1377–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drossman DA, Hasler WL. (eds) Rome IV – Functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1257–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rasmussen S, Jensen TH, Henriksen SL, et al. Overlap of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome in the general population. Scand J Gastroenterol 2015; 50: 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci 1993; 38: 1569–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 21: 1365–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mehuys E, Bortel LV, De Bolle L, et al. Self-medication of upper gastrointestinal symptoms: a community pharmacy study. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43: 890–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dinning PG, Jones M, Hunt L, et al. Factors analysis identifies subgroups of constipation. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 1468–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eltringham MT, Khan U, Bain IM, et al. Functional defecation disorder as a clinical subgroup of chronic constipation: analysis of symptoms and physiological parameters. Scand J Gastroenterol 2008; 43: 262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wiesner M, Naylor SJ, Copping A, et al. Symptom classification in irritable bowel syndrome as a guide to treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aktas A, Walsh D, Rybicki L. Symptom clusters: myth or reality? Palliat Med 2010; 24: 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Oudenhove L, Holvoet L, Vandenberghe J, et al. Do we have an alternative for the Rome III gastroduodenal symptom-based subgroups in functional gastroduodenal disorders? A cluster analysis approach. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 23: 730–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boltanski L. Les usages sociaux du corps. Annales. Economies, Sociétés, Civilisations, 1971; 26: 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carruthers HR, Miller V, Morris J, et al. Using art to help understand the imagery of irritable bowel syndrome and its response to hypnotherapy. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2009; 57: 162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carruthers HR, Morris J, Tarrier N, et al. Reactivity to images in health and irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31: 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frexinos J, Denis P, Allemand H, et al. Descriptive study of digestive functional symptoms in the French general population. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1998; 22: 785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, et al. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 3: 543–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Talley NJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders as a public health problem. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2008; 20(Suppl. 1): 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang L. Review article: epidemiology and quality of life in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20(Suppl. 7): 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tack J, Masaoka T, Janssen P. Functional dyspepsia. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2011; 27: 549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]