Abstract

Intraabdominal desmoid tumours are rare and can cause intestinal obstruction. Based on the review of the literature, surgical resection with negative margins and adjuvant chemotherapy is the optimal strategy for treatment of this pathology.

Keywords: Desmoid tumours, caecum, colon

Introduction

Desmoid tumours are extremely rare, causing 0.03% of all neoplasms and less than 3% of all soft tissue tumours.1 They are locally aggressive neoplasias, which do not show metastatic tendency. While most cases have an asymptomatic course, urgent surgical interventions have been reported due to reasons such as intestinal obstruction, perforation and abscess formation.2 We present the case of a 47-year-old male who developed an intestinal obstruction from a desmoid tumour of the caecum.

Case report

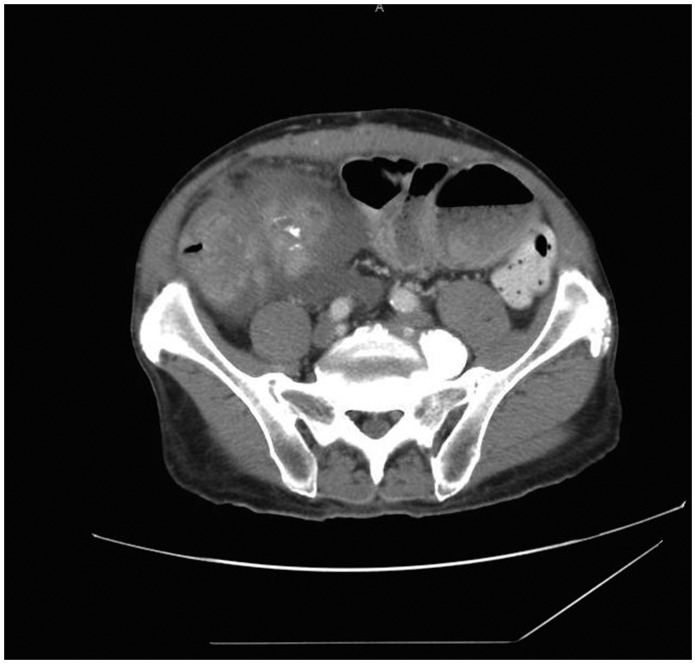

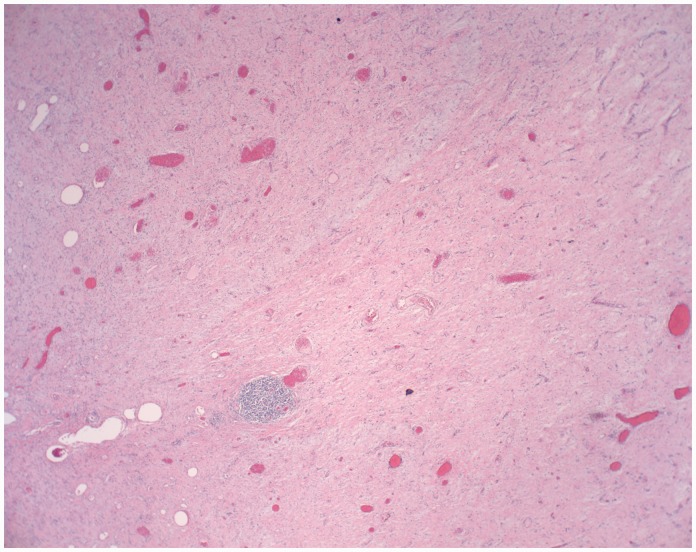

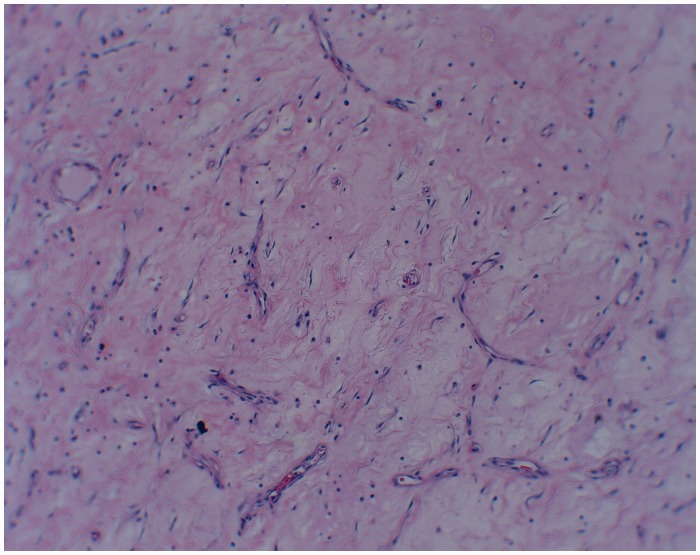

A 47-year-old male with a past medical history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, end-stage renal failure and exploratory laparotomy for a gunshot wound with subsequent ventral hernia repair presented with one month of abdominal pain. The patient characterised the pain as intermittent and localised to the right lower quadrant. A computed tomography scan Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a 7.7 × 10 cm caecal mass along with partially obstructed loops of small bowel (Figure 1). Intraoperatively he was found to have a large mass in the caecum extending up into the right colon to which the distal ileum and appendix were adherent. He also had palpable enlarged lymph nodes extending down to the root of the right mesocolon. He was also found to have thickened and dilated distal small bowel loops consistent with long-standing obstruction. An ileocolic anastomosis was successfully created and the patient recovered uneventfully. Pathology revealed a 10 × 9 × 5 cm desmoid tumour which stained positive for beta-catenin (Figures 2 and 3). The margins were negative as were the seven resected lymph nodes. He was discharged home on postoperative day 7 and continues to do well on outpatient follow-up.

Figure 1.

Abdominal tomography image demonstrating the large mass originating in the caecum.

Figure 2.

Histological slide of specimen – different staining specimen.

Figure 3.

Histological slide of specimen – collagen staining.

Discussion

Desmoid tumours are rare well-differentiated and aggressive musculoaponeurotic fibromatosis tumours, considered as grade 1 fibrosarcoma.3 These tumours are characterised by their propensity for slow, incessant growth and invasion of contiguous structures. Although locally aggressive, these tumours do not metastasise.4 On computed tomography scan, most desmoid tumours appear as well-circumscribed homogeneous masses that may be isodense or hyperdense relative to muscle.5 Histological assessment is mandatory for differentiating desmoid tumours from other neoplasms such as gastrointestinal stromal tumours, lymphoma, pleomorphic sarcoma and fibrosarcoma. Microscopically they are composed of spindle- or stellate-shaped fibroblastic cells embedded in a collagenous stroma. The spindle cells usually stain for vimentin and smooth muscle actin and nuclear beta-catenin.6,7

Depending upon the location, most desmoids present as slow-growing, painless masses.8 Mesenteric fibromatosis commonly arises from the mesentery of the small bowel but can also originate from the ileocolic mesentery, gastrocolic ligament and omentum.9 Intraabdominal desmoids are usually asymptomatic until their size causes compression of surrounding viscera. This compression can lead to intestinal obstruction, ischaemic bowel secondary to vascular compression and hydronephrosis due to ureteric compression.10 Although intestinal obstruction has been described as a potential complication of intraabdominal desmoid tumours, only seven prior cases have been reported in the literature (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cases of intraabdominal desmoid tumours causing intestinal obstruction.

| Author | Year | Age | Presentation | Operation | Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdalla et al.6 | 2016 | 54M | Altered mental status with abdominal pain | Laparotomy with ileal and ileocaecal resections Planned second look with jejunoileal and ileocolic anastamoses Laparotomy and drain placement for jejunoileal anastomotic leak | 7 cm mass at ileum + 6 cm mesoappendix mass +Beta-catenin +Actin +Vimentin |

| Venkat et al.8 | 2010 | 46F | Abdominal pain | Laparotomy with right hemicolectomy | 6.2 cm mass of the right colon +Beta-catenin +Desmin |

| Lasseur et al.3 | 2016 | 32F | Incidentally discovered abdominal mass | Laparotomy with en bloc resection of the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum and superior mesenteric artery and vein Laparotomy for hemiperitoneum | 7.5 cm mass of the small bowel at the ligament of Treitz +Beta-catenin |

| Aggarwal et al.11 | 2015 | 28F | Early satiety | Laparotomy with resection of left internal oblique muscle with mesh repair, resection of right external iliac vein | Large mass adherent to anterior rectus sheath and parietal peritoneum |

| Mazeh et al.9 | 2006 | 55M | Early satiety | Laparotomy with gastrojejunostomy | 20 cm duodenal mass |

| Ozmen et al.12 | 2004 | 57M | Abdominal pain | Laparotomy with partial duodenojejunectomy and right hemicolectomy | 10 cm tumour at jejunum, proximal duodenum and ascending colon +Actin +Vimentin |

| Holubar et al.13 | 2006 | 52M | Abdominal pain | Laparotomy with en bloc resection of the terminal ileum and superior mesenteric artery and vein | 22 cm mass at terminal ileum +Beta-catenin |

Most of these tumours occur sporadically; however, patients with Gardner’s syndrome are at higher risk than others. The incidence of abdominal wall and mesenteric desmoids in patients with Gardner’s syndrome ranges between 4 and 29%, and the tumours typically occur after abdominal surgery.14 In the presence of polyposis syndromes, patients should be managed at a specialist colorectal unit with surgery reserved only when absolutely necessary. In these patients the high recurrence rate mandates medical therapies such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tamoxifen and chemotherapy to be used as first- and second-line therapy.

This contrasts with the management of sporadic intraabdominal desmoid tumours, which should be managed in a specialist sarcoma unit by a multidisciplinary team.6 Early referral to a centre that specialises in multimodality care of sarcomas is warranted. In asymptomatic patients, close observation is often the preferred strategy. Patients with symptoms are typically treated, given the inevitably progressive growth of desmoid tumours. Surgery with a wide margin of resection is the preferred treatment whenever feasible.15 Patients with sporadic desmoid tumours tend to have low recurrence rates after resection.6 All of the patients who presented with obstruction underwent oncologic resections of the involved intestinal segments with no reported recurrences.3,6,8,9,11–13

Complete resection of the tumour with negative microscopic margins is the standard surgical goal but is often constrained by anatomic boundaries.10 One recent review of multimodal therapy for desmoid tumours in all anatomic locations showed that surgery supplemented with radiotherapy had reduced recurrence rates for patients with both positive and negative surgical margins. Radiotherapy alone also had promising outcomes for local control.16 For patients with recurrence despite local therapy, systemic medical therapy is often prescribed. Options include tamoxifen, which is thought to suppress desmoid growth due to the presence of estrogen receptor beta on tumour cells, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as Sulindac, and doxorubicin and methotrexate with vinca alkaloid-based chemotherapy. Post-treatment surveillance includes clinical examination and radiographic assessment every six months for at least three years and then yearly thereafter.8

Conclusion

Intraabdominal desmoid tumours are rare and may result in intestinal obstruction. Based on the review of the literature, resection with negative margins with consideration towards adjuvant radiotherapy is the optimal treatment. In patients with obstruction, oncologic bowel resection with primary anastomosis appears to be an acceptable surgical strategy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the faculty and staff at NYP Brooklyn Methodist Hospital who supported our endeavors.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

Given that this was a retrospective chart review, no formal IRB approval was required. Informed consent was obtained from the patient (which is available upon request).

Guarantor

SR

Contributorship

AJ wrote the manuscript. SR performed the literature review. PZ and JR edited the manuscript. PG was the primary surgeon who spearheaded the submission of the manuscript.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Naga Jayanthi and Chung Lim

References

- 1.Shields CJ, Winter DC, Kirwan WO, Redmond HP. Desmoid tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol 2001; 27: 701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jalini N, Hemming D, Bhattacharya V. Intraabdominal desmoid tumour presenting with perforation. Surgeon 2006; 4: 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasseur A, Pasquer A, Feugier P, Poncet G. Sporadic intra-abdominal desmoid tumor: a unusual presentation. J Surg Case Rep 2016; 5: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Easter DW, Halasz NA. Recent trends in the management of desmoid tumors. Summary of 19 cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg 1989; 210: 765–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faria SC, Iyer RB, Rashid A, Ellis L, Whitman GJ. Desmoid tumor of the small bowel and the mesentery. Am J Roentgenol 2004; 183: 118–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdalla S, Wilkinson M, Wilsher M, Uzkalnis A. An atypical presentation of small bowel obstruction and perforation secondary to sporadic synchronous intra-abdominal desmoid tumours. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016; 20: 147–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinagare AB, Ramaiya NH, Jagannathan JP, Krajewski KM, Giardino AA, Butrynski JE, et al. A to Z of desmoid tumors. Am J Roentgenol 2011; 197: W1008–W1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkat D, Levine E, Wise WE., Jr Abdominal pain and colonic obstruction from an intra-abdominal desmoid tumor. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 6: 662–665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazeh H, Nissan A, Simanovsky N, Hiller N. Desmoid tumor causing duodenal obstruction. Isr Med Assoc J 2006; 8: 288–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peled Z, Linder R, Gilshtein H, Kakiashvili E, Kluger Y. Cecal fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) mimicking periappendicular abscess: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2012; 5: 511–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aggarwal G, Shukla S, Maheshwari A, Mathur R. Desmoid tumour: a rare etiology of intestinal obstruction. Pan Afr Med J 2015; 22: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozmen V, Polat C, Yilmaz S, Ozmen T, Selcuk E. An intraabdominal desmoid tumor in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Case Rep 2004; 5: 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holubar S, Dwivedi AJ, O’Connor J. Giant mesenteric fibrosis presenting as small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg 2006; 72: 427–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Einstein DM, Tagliabue JR, Desai RK. Abdominal desmoids: CT findings in 25 patients. Am J Roentgenol 1991; 157: 275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith AJ, Lewis JJ, Merchant NB, Leung DH, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Surgical management of intra-abdominal desmoid tumours. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 608–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuyttens JJ, Rust PF, Thomas CR, Jr, Turrisi AT., 3rd Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with aggressive fibromatosis or desmoid tumors: a comparative review of 22 articles. Cancer 2000; 88: 1517–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]