Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate relationships between caregiver-reported sensory processing abnormalities, and the physiological index of auditory over-responsiveness evaluated using acoustic startle response measures, in children with autism spectrum disorders and typical development. Mean acoustic startle response magnitudes in response to 65–105 dB stimuli, in increments of 10 dB, were analyzed in children with autism spectrum disorders and with typical development. Average peak startle latency was also examined. We examined the relationship of these acoustic startle response measures to parent-reported behavioral sensory processing patterns in everyday situations, assessed using the Sensory Profile for all participants. Low-threshold scores on the Sensory Profile auditory section were related to acoustic startle response magnitudes at 75 and 85 dB, but not to the lower intensities of 65 dB. The peak startle latency and acoustic startle response magnitudes at low-stimuli intensities of 65 and 75 dB were significantly related to the low-threshold quadrants (sensory sensitivity and sensation avoiding) scores and to the high-threshold quadrant of sensation seeking. Our results suggest that physiological assessment provides further information regarding auditory over-responsiveness to less-intense stimuli and its relationship to caregiver-observed sensory processing abnormalities in everyday situations.

Keywords: acoustic startle response, autism spectrum disorders, hypersensitivity, phenotype, response latency

Introduction

Sensory abnormalities are frequently present in individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD; Gomes et al., 2008; Marco et al., 2011). They have been considered a key feature of ASD since the pioneering reports of Kanner (1943). In particular, difficulties in the ability to accurately process and interpret auditory information are often found in ASD (O’Connor, 2012). Auditory over-responsiveness (AOR) is the most common sensory-perceptual abnormality in individuals with ASD (Gomes et al., 2008). This abnormality has been reported to interrupt behavioral adaptation (Lane et al., 2010), has been associated with family impairment (where parents have stated that their children’s behavior, personality, or special needs were associated with difficulty completing daily family tasks; Ben-Sasson et al., 2013; Carter et al., 2011), and sometimes even requires therapeutic intervention (Stiegler and Davis, 2010).

Measures of sensory responsiveness include methods ranging from behavioral measurement (self-report or caregiver-report) to electrophysiological measurement (Reynolds and Lane, 2008). Given the growing use of translational research methods in the study of psychiatric disorders, including developmental disorders, uncovering the biological basis of sensory abnormalities may lead to better management and treatment of such abnormalities. Although sensory over-responsiveness is considered to occur independently of a recognized childhood psychiatric diagnosis, it is also a relatively frequent comorbid condition of a number of recognized diagnoses (Van Hulle et al., 2012). Moreover, it is sometimes quite difficult to distinguish sensory over-responsiveness from childhood behavioral problems. Thus, investigation of the relation between neurophysiological biomarkers and caregiver-observed sensory over-responsivity may deepen the understanding of AOR in ASD.

As people with autism are reported to have altered thresholds to sensory stimuli (Dunn, 2001), and many individuals with ASD suffer from a combination of under- and over-responsiveness (Baranek et al., 2006), a focus on physiological indexes measured using varied intensity stimuli may provide more detailed information on sensory abnormalities in ASD. Furthermore, the association between the behavioral sensory abnormalities seen in ASD in everyday situations and neurophysiological indexes of sensory reactivity evaluated using low- to high-stimuli intensity has not been thoroughly investigated. Some studies have suggested that relationships exist between self-reported or caregiver-reported Sensory Profile (SP) scores and physiological indexes such as event-related potentials (Orekhova et al., 2012), electroencephalographm, magnetoencephalogram (Marco et al., 2012; Matsuzaki et al., 2012, 2014), functional magnetic resonance imaging (Green et al., 2013), or electrodermal activity (Schoen et al., 2009). However, these studies analyzed the relationship using only a single intensity stimulus, which did not differ much from the stimulus intensity usually designed for testing participants with typical development (TD). People with sensory over-responsiveness may respond excessively to lower intensity stimuli. Comparing responses over several intensities of stimuli may reveal more details on the relationship between physiological responses and behavioral sensory responses.

The acoustic startle response (ASR) and its modulation, such as prepulse inhibition (PPI) and habituation (HAB), are commonly used neurophysiological measures for evaluating aspects of information processing. As the ASR can be examined using similar nonlinguistic experimental paradigms across ethnic groups and species, it is considered one of the most promising neurophysiological measures for translational research (Takahashi et al., 2011). ASR is a fast twitch of facial and body muscles evoked by a sudden and intense acoustic stimulus (Koch, 1999). This response pattern is suggestive of a protective function against injury from a predator or physical blow, as well as for preparation for a flight response. PPI and HAB are frequently evaluated indexes of startle modulation. PPI is usually defined as a reduction in the startle response due to weak sensory pre-stimulation and is widely regarded as a robust and reliable neurophysiological index of sensorimotor gating. HAB is defined as a decrement in behavioral responses to repeated presentations of an identical, initially novel, stimulus, which is not due to sensory adaption or effector fatigue (Geyer and Braff, 1982). Reduced HAB to the ASR is also thought to reflect impaired gating of repeatedly presented simple stimuli, which may result in cognitive disruption by sensory overload.

Recent studies (Takahashi et al., 2014, 2016) have examined the ASR using low- to high-intensity stimuli, peak ASR latency, and ASR modulation (HAB and PPI) in children with ASD and TD. The ASR magnitude to acoustic stimuli of 85 dB or lower was higher in children with ASD compared with TD, and peak startle latency (PSL) was also more prolonged. Although significant differences in ASR modulation of HAB or PPI were not found between ASD and TD children, these ASR modulation indexes were significantly related to the behavioral problems of children (Takahashi et al., 2016). Thus, comprehensive investigation of ASR and its modulation may reveal promising biomarkers for improvements to the understanding of the neurophysiological impairments underlying ASD and other mental health problems in children.

Given this, this study sought to examine properties of the ASR in children with ASD and TD, including the startle magnitude to acoustic stimuli of varying intensities, PSL, HAB, and PPI, and to investigate their relationship with caregiver-reported sensory processing abnormalities. Based on earlier studies, we hypothesized that the ASR in response to low-intensity stimuli could be used as a biomarker for AOR, thereby allowing evaluation of the biological features of AOR, which may be difficult to detect in everyday situations.

Methods

Participants

Fifteen Japanese children with ASD (aged 8–16 years) and 29 typically developing (TD) Japanese children (aged 8–16 years) were recruited to participate in the study. Participants were recruited through local advertisements and diagnosed by an experienced child psychiatrist on the basis of current behavior and developmental history, as determined by reviews of medical records and clinical interviews guided by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text rev.; DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000). Diagnoses were confirmed using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al., 1995) and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000). The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Revision (WISC-III; Wechsler, 1991) was used to estimate IQ. The demographic characteristics of all participants are presented in Table 1. The ASD and control groups did not differ significantly in gender, age, or estimated IQ. All children had an estimated IQ above 70 and were nonsmokers. No children were on psychotropic medication. Exclusion criteria included known hearing loss and central nervous system abnormalities other than autism. Additionally, control participants were excluded if they had any history of psychiatric diagnoses or learning disabilities.

Table 1.

Demographic data, Sensory Profile scores, and startle measures of the participants.

| Typical development (N = 29) | Autism spectrum disorders (N = 15) | χ 2 | Df | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male:female | 17: 12 | 12: 3 | 2.011 | 1 | 0.156 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | U | p-value | Effect size (r) | |

| Age (years) | 11.8 | 2.6 | 10.5 | 2.0 | 147.5 | 0.083 | −0.26 |

| Estimated IQ | 103.4 | 17.9 | 99.1 | 21.7 | 58.5 | 0.353 | −0.18 |

| Peak startle latency (ms) | 67.7 | 9.3 | 89.3 | 15.8 | 57.5 | <0.001*** | −0.58 |

| Acoustic startle magnitude (µV) | |||||||

| 65 dB | 33.4 | 16.3 | 54.1 | 28.0 | 91.5 | 0.004** | −0.44 |

| 75 dB | 29.6 | 10.5 | 51.9 | 30.6 | 89.5 | 0.003** | −0.45 |

| 85 dB | 33.2 | 11.2 | 69.1 | 55.6 | 98 | 0.006** | −0.42 |

| 95 dB | 36.3 | 11.5 | 83.9 | 85.1 | 100 | 0.010** | −0.40 |

| 105 dB | 45.4 | 15.2 | 84.9 | 67.4 | 130 | 0.105 | −0.25 |

| Habituation (%) | 17.6 | 16.8 | 17.6 | 17.3 | 118 | 0.754 | −0.05 |

| Prepulse inhibition (%) | |||||||

| 65 dB prepulse | 25.5 | 17.0 | 18.9 | 15.4 | 131 | 0.258 | −0.18 |

| 70 dB prepulse | 23.3 | 16.8 | 15.7 | 18.0 | 125 | 0.260 | −0.18 |

| 75 dB prepulse | 33.4 | 18.2 | 32.5 | 20.0 | 188 | 0.831 | −0.03 |

| Sensory Profile scores | |||||||

| Auditory section | |||||||

| High-threshold scores | 4.2 | 1.5 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 93.5 | 0.002** | −0.48 |

| Low-threshold scores | 7.8 | 2.1 | 14.3 | 4.4 | 35 | <0.001*** | −0.69 |

| Quadrant scores | |||||||

| Low registration | 18.2 | 4.7 | 35.3 | 10.7 | 25.5 | <0.001*** | −0.72 |

| Sensation seeking | 31.2 | 5.8 | 55.2 | 15.1 | 19.5 | <0.001*** | −0.74 |

| Sensory sensitivity | 25.1 | 4.4 | 38.0 | 7.7 | 31.5 | <0.001*** | −0.70 |

| Sensation avoiding | 41.0 | 9.0 | 71.4 | 11.0 | 7 | <0.001*** | −0.79 |

| Total score | 163.1 | 31.9 | 285.8 | 52.3 | 10.5 | <0.001*** | −0.77 |

Typical development: autism spectrum disorders: (peak startle latency) 23:11; acoustic startle magnitude (65 dB) 23:10; (75 dB) 23:10; (85 dB) 23:10; (95 dB) 22:9; (105 dB) 20:9; (Habituation) 12:8; prepulse inhibition (65 dB prepulse) 15:7; (70 dB prepulse) 21:8; (75 dB prepulse) 22:9.

Mann–Whitney U-test; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Japan. All participants and their parents gave written informed consent after study procedures had been fully explained to them and before inclusion in the study.

Assessment of SP

The Japanese version of the SP (Dunn, 1999) was used to assess sensory processing. The SP consists of 125 behavioral items arranged over 14 sensory processing categories, including auditory, visual, vestibular, touch, taste/smell, movement, body position, activity level, and emotional/social. Caregivers report the frequency, in normal daily life, of their child’s responses to the items. The SP takes about 30 min to complete, and the original version (Dunn, 1999) is a reliable and valid tool for assessing the sensory processing abilities of children of 3–11 years of age, while the Japanese version (Ito et al., 2013) is valid for use on people of 3–82 years of age.

The caregiver (usually the parent) is asked to respond to each item on a five-point Likert scale, indicating how frequently the child engages in a particular behavior (Japanese version: 5 = always: when presented with the opportunity, the child responds in the manner described every time, or 100% of the time; 4 = frequently, or at least 75% of the time; 3 = occasionally, or 50% of the time; 2 = seldom, or 25% of the time; and 1 = never, when presented with the opportunity, the child never responds in this fashion, or 0% of the time). The SP items are scored so that frequent behaviors are undesirable. In the Japanese version, more typical children tend to engage in these behaviors less frequently, and thus tend to have low scores, while high scores reflect greater symptoms.

Some of the SP items are labeled as low- and high-threshold items. High-threshold items measure an individual’s lack of response or need for more intense stimuli, which is under- or hypo-responsiveness. Low-threshold items measure a person’s awareness, irritation, or annoyance with sensory stimuli, which is over-responsiveness.

Based on Dunn’s Model (Dunn, 2001), the SP includes quadrant scores, which represent four unique continua of behavior. Each quadrant represents the interaction between the neural threshold (high to low) of the child and the behavioral strategy (from active to passive) that the child uses to respond to the sensory information: low registration (a passive response to a high threshold), sensation seeking (an active response to a high threshold), sensory sensitivity (a passive response to a low threshold), and sensation avoiding (an active response to a low threshold). Information gained from the SP category and quadrant scores provides an indication of where sensory processing interventions may be required.

In this study, we calculated the total SP scores, the scores of the four quadrants, and the high- and low-threshold scores of the SP auditory section to investigate their relationships with the neurophysiological indexes of ASR. Standard scoring procedures were used for calculating the SP category, quadrant, and total scores.

Startle response measurement

A commercial computerized human startle-response monitoring system (Startle Eyeblink Reflex Analysis System Map1155SYS, Nihonsanteku Co., Osaka, Japan) was used to deliver acoustic startle stimuli and to record and score the corresponding electromyographic (EMG) activity. All auditory stimuli and background noise (broadband white noise: 1.346 Hz to 22.05 KHz) were delivered binaurally to participants through stereophonic headphones. Startle eyeblink EMG responses were recorded from the left orbicularis oculi muscle. The eyeblink magnitude of every startle response was defined as the voltage of the peak EMG activity within a latency window of 20–120 ms following the startle-eliciting stimulus onset. Data were stored and exported for analyses in microvolt values.

Participants were tested in a startle paradigm that consisted of three blocks, with continuously presented 60 dB sound pressure level (SPL) background white noise (Supplementary Figure 1). The startle paradigm consisted of 68 trials presented in a fixed order, separated by inter-trial intervals of 10–20 s (15 s on average). The session lasted approximately 22 min, including 5 min for acclimation to the background noise.

Pulse stimuli consisted of broadband white noise with an instantaneous rise/fall time of 40 ms and presented in a fixed pseudorandom order. In block 1, pulse-alone (PA) stimuli were presented at 65–105 dB SPL in 10 dB increments (5 intensities). PA stimuli were presented six times at each intensity, beginning with low-intensity stimuli and progressing to high-intensity stimuli; block 1 therefore had 30 trials. Block 2 consisted of PA trials at 105 dB SPL, or prepulse (PP) trials consisting of a prepulse at one of three intensities (65, 70, and 75 dB SPL), followed by a 105 dB SPL pulse. Each condition was performed eight times, resulting in a total of 32 trials. The prepulse stimuli also consisted of broadband white noise, with an instantaneous rise/fall time of 20 ms. The lead interval (from prepulse onset to pulse onset) was set to 120 ms. In block 3, the startle response for PA trials at 105 dB SPL was recorded six times to observe HAB.

The following startle measures were examined: (1) average startle eyeblink magnitude in response to each pulse intensity of block 1, designated as ASR65, ASR75, ASR85, ASR95, and ASR105; (2) the average PSL, defined as the average peak-startle latency across trials with an ASR larger than 60 µV in block 1; (3) HAB of the startle response during the session, defined as the percentage of ASR amplitude reduction at 105 dB SPL between block 1 and block 3, and calculated according to the formula (1 − average eyeblink amplitude of startle response in block 3/average eyeblink amplitude of startle response in block 1) × 100; (4) PPI65, PPI70, PPI75, PPI at prepulse intensities of 65, 70, and 75 dB SPL, respectively. The PPI at each prepulse intensity was defined as the percentage of amplitude reduction between PA and PP trials in block 2 and were calculated using the following formula: (1 − average eyeblink amplitude of startle response to PP trials in block 2/average eyeblink amplitude of startle response to PA trials in block 2) × 100. Trials were discarded if the voltage of their peak EMG activity was above 60 µV within a latency window of 0–20 ms following the startle-eliciting stimulus onset. Startle measures were not calculated for conditions in which more than half of the trials had been discarded. The number of discarded trials did not differ between the TD and ASD groups. One boy with ASD was unable to tolerate the startle stimuli and did not complete the session. His data were excluded from the final analysis.

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical proportions. The Shapiro–Wilk W statistic was used to test for a normal distribution (p < 0.05), with the result that the majority of startle measures and SP scores were non-normally distributed, except for PSL (W = 0.962, p = 0.636), ASRI65 (W = 0.931, p = 0.203), HAB (W = 0.971, p = 0.818), PPI70 (W = 0.963, p = 0.655), PPI75 (W = 0.970, p = 0.790), and SP Sensation Avoiding quadrant score (W = 0.918, p = 0.119). Therefore, we performed nonparametric analyses. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare SP scores and startle measures, and Spearman’s rank-order correlations were used to examine the relationships between startle measures and SP scores. All p-values reported are two-tailed. Statistical significance was indicated by p-values < 0.05. The alpha-level was corrected for multiple comparisons using a value of <0.005, as there were 10 indexes of ASR under investigation. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Ver. 21 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Differences in startle measures and SP scores between children with ASD and controls

PSL was significantly prolonged in children with ASD (Table 1) in comparison with children with TD. Additionally, children with ASD exhibited significantly greater ASR magnitude at stimulus intensities of 95 dB or lower. No significant difference in HAB or PPI at any prepulse intensity was found between the TD and ASD groups. All SP scores were significantly higher in the ASD group than in the controls. No gender differences in the SP scores or the startle measures were found in either group.

Relationship of startle measures to SP scores

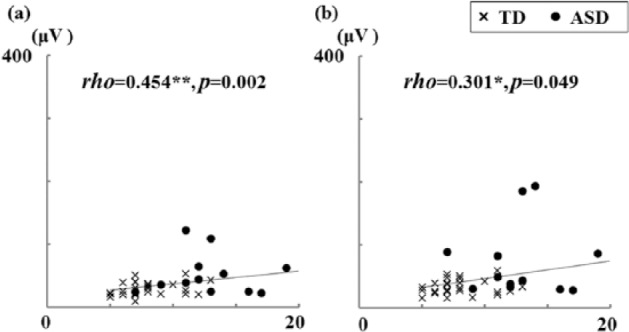

The significant relationships between startle measures and SP scores are illustrated in Figure 1 (low-threshold scores of the SP auditory section) and Table 2 (total SP scores and the four quadrant scores). As behavioral traits related to ASD are suggested to present a continuous distribution across the population (Constantino and Todd, 2003), we did not divide the children into ASD and control groups when evaluating the relationships between startle measures and clinical characteristics.

Figure 1.

Scatterplots of startle magnitudes according to low-threshold scores of the auditory section of the Sensory Profile: (a) ASR75 and (b) ASR85, for low-threshold score.

ASD: autism spectrum disorders; ASR75 and ASR85: average startle eyeblink magnitude at stimulus intensities of 75 and 85 dB, respectively; TD: typical development.

Spearman’s rank-order correlation; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Table 2.

Relationships between startle measures and Sensory Profile scores.

| N | Peak startle latency |

Acoustic startle magnitude |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 | 65 dB |

75 dB |

85 dB |

95 dB |

105 dB |

||

| 43 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 41 | |||

| Sensory Profile scores | |||||||

| Quadrant scores | |||||||

| Low registration | rho | 0.372 | 0.286 | 0.387 | 0.170 | 0.217 | 0.038 |

| p | 0.014* | 0.063 | 0.010** | 0.276 | 0.167 | 0.813 | |

| Sensation seeking | rho | 0.380 | 0.432 | 0.501 | 0.405 | 0.415 | 0.215 |

| p | 0.012* | 0.004** | 0.001** | 0.007** | 0.006** | 0.176 | |

| Sensory sensitivity | rho | 0.250 | 0.430 | 0.499 | 0.359 | 0.326 | 0.144 |

| p | 0.105 | 0.004** | 0.001** | 0.018* | 0.035* | 0.368 | |

| Sensation avoiding | rho | 0.379 | 0.419 | 0.485 | 0.330 | 0.352 | 0.176 |

| p | 0.012* | 0.005** | 0.001** | 0.031* | 0.022* | 0.270 | |

| Total score | rho | 0.374 | 0.401 | 0.479 | 0.317 | 0.367 | 0.159 |

| p | 0.013* | 0.008** | 0.001** | 0.038* | 0.017* | 0.321 | |

Spearman’s rank-order correlation; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Significant relationships between startle measures and low-threshold auditory SP scores were only found for ASR75 and ASR85 (Figure 1). Significant relationship for ASR75 remained even after correcting for multiple comparisons. We did not find any significant relationships between low-threshold auditory SP scores and any other ASR measures. In addition, there were also no significant correlations between high-threshold auditory SP scores and any of the ASR measures.

With the exception of low registration, the total SP and quadrant scores were significantly correlated with average ASR magnitude at stimulus intensities of 95 dB or lower (Table 2). Most of the relationship for ASR65 and ASR75 remained significant even after correcting for multiple comparisons. Similarly, apart from sensory sensitivity, the total SP scores and quadrants were significantly correlated with PSL (Table 2). The low-registration quadrant was also significantly related to average ASR magnitude at stimulus intensities of 75 dB. We did not find any other significant relationships of total SP and quadrant scores to startle measures.

These relationships were also investigated within each participant groups as all of the SP scores differed significantly between diagnoses. Significant associations remained between the SP sensory seeking quadrant scores (rho = 0.464, p = 0.011) and sensory sensitivity quadrant scores (rho = 0.402, p = 0.031) to ASR75 remained in the TD group. No other significant relationships were detected between SP scores and startle measures in either group.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the relationships of neurophysiological biomarkers of AOR (measured by the ASR and its modulation) to caregiver-observed phenotypes of sensory processing abnormalities. These abnormalities were assessed using the SP measures in children with ASD and TD. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine behavioral sensory processing abnormalities in everyday situations in relation to physiological markers of AOR at several intensities of acoustic stimuli. Low-threshold scores in the auditory SP section were only related to ASR at magnitudes of 75 and 85 dB, not to the lower intensities of 65 dB. The ASR magnitudes to 95 dB or less were significantly related to the total SP scores, low-threshold quadrants (sensory sensitivity and sensation avoiding), and the high-threshold quadrant of sensation seeking. The ASR magnitude to 75 dB stimuli was also related to the low-registration quadrant. Our results indicate that although AOR to low-intensity stimuli of 65 dB is difficult to detect in everyday situations, observed sensory abnormalities such as sensory seeking, which is considered as a high-threshold aspect of sensory abnormality, may partly result from AOR to low-intensity stimuli in the range of 65–95 dB.

We also found significant relationships between prolonged PSL and the following: high total SP scores, the low-threshold quadrant of sensation avoiding, the high-threshold quadrants of sensation seeking, and low registration. Prolonged response latencies to sensory stimuli of 50–100 ms, such as the latency delay of the middle-latency M50/M100 response, have frequently been reported in ASD and have been considered to be promising biomarkers of ASD (Port et al., 2015). Latency delay in the M50/M100 response has also been reported to be related to the SP auditory item score (Matsuzaki et al., 2012, 2014). In addition, recent studies showed that peak ASR latency was prolonged in ASD children compared with TD children (Takahashi et al., 2014, 2016) and was related to quantitative autistic traits, in addition to behavioral and emotional problems (Takahashi et al., 2016). Our results suggest that prolonged response latency may be a distinguishing trait of the atypical phenotype exhibited in ASD sensory processing abnormalities. As ASR is considered to be one of the most promising neurophysiological measures for translational research, future studies using aspects of this approach, such as PSL, and startle magnitude in response to weak acoustic stimuli, may extend translational research into ASD and help to define its underlying neural mechanisms.

A major limitation of this study was the small sample size of the ASD group, especially compared with the larger control group. Although we were able to detect significantly prolonged startle latencies and greater startle magnitudes in response to weak stimuli in ASD individuals, our sample size may have been insufficient for detecting other significant differences or relationships. Although we could not find any relationship between ASR modulation (HAB and PPI) and SP scores, this may have been due to the small ASD sample size. A second limitation relates to our startle paradigm. Several studies have reported atypical pitch processing in individuals with autism (Bonnel et al., 2003; Heaton et al., 2008), and it is possible that the startle response to weak stimuli is elicited by exposure to a specific pitch range, as we used broadband white noise in our study. Future investigations on the ASR using different pitches of weak acoustic stimuli are required. Additionally, none of our participants exhibited intellectual disabilities. As we included only ASD children with IQs >70 and IQ-matched controls, we were able to prevent the high rates of participant rejection reported in a previous study (Ornitz et al., 1993). However, ASD individuals with intellectual disabilities may exhibit different ASR profiles. Thus, studies with larger sample sizes, which include participants with intellectual disabilities, should be conducted in the future. Finally, we did not investigate stimuli with intensities over 105 dB. This may have been responsible for the failure to find a significant relationship with high-threshold scores of the SP auditory section. However, the use of such high-stimuli intensities would be highly questionable and possibly unethical in a situation where a significant proportion of people with ASD are known to have AOR (Gomes et al., 2008) and may therefore be intolerant of such stimuli. In contrast, subjects with over-responsivity might have an atypical response to acoustic stimuli of less than 65 dB. ASD is a set of widely heterogeneous neurodevelopmental conditions, and future studies specifically designed to assess participants with over- or under-responsiveness using acoustic stimuli less than 65 dB or more than 105 dB (only for those without AOR), respectively, might further reveal the mechanisms underlying these atypical sensory responses.

Conclusion

The current results suggest that neurophysiological biomarkers of AOR, evaluated by ASR at varying stimuli intensities, can reveal the biological pathophysiology related to AOR in various sensory processing abnormalities observed in everyday situations. Thus, examination of neurophysiological biomarkers evaluated by ASR may not only extend the understanding of the neurophysiological basis of sensory processing abnormalities but also the understanding of problems in the everyday lives of children with ASD.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, AUT680497_Lay_Abstract for Relationship between physiological and parent-observed auditory over-responsiveness in children with typical development and those with autism spectrum disorders by Hidetoshi Takahashi, Takayuki Nakahachi, Andrew Stickley, Makoto Ishitobi and Yoko Kamio in Autism

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, AUT680497_Supplementary-material for Relationship between physiological and parent-observed auditory over-responsiveness in children with typical development and those with autism spectrum disorders by Hidetoshi Takahashi, Takayuki Nakahachi, Andrew Stickley, Makoto Ishitobi and Yoko Kamio in Autism

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the participants and parents who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (23890257, 24591739), Intramural Research Grant (23-1, 26-1) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP, Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H19-KOKORO-006 and H20-KOKORO-004), and the Center of Innovation Program from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2000) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Text revision. Washington, DC: APA. [Google Scholar]

- Baranek GT, David FJ, Poe MD, et al. (2006) Sensory Experiences Questionnaire: discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 47: 591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson A, Soto TW, Martinez-Pedraza F, et al. (2013) Early sensory over-responsivity in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders as a predictor of family impairment and parenting stress. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 54: 846–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnel A, Mottron L, Peretz I, et al. (2003) Enhanced pitch sensitivity in individuals with autism: a signal detection analysis. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 15: 226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Ben-Sasson A, Briggs-Gowan MJ. (2011) Sensory over-responsivity, psychopathology, and family impairment in school-aged children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 50: 1210–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN, Todd RD. (2003) Autistic traits in the general population: a twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry 60: 524–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. (1999) Sensory Profile User’s Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. (2001) The sensations of everyday life: empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 55: 608–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Braff DL. (1982) Habituation of the Blink reflex in normals and schizophrenic patients. Psychophysiology 19: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes E, Pedroso FS, Wagner MB. (2008) Auditory hypersensitivity in the autistic spectrum disorder. Pró-Fono 20: 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SA, Rudie JD, Colich NL, et al. (2013) Overreactive brain responses to sensory stimuli in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 52: 1158–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton P, Williams K, Cummins O, et al. (2008) Autism and pitch processing splinter skills: a group and subgroup analysis. Autism 12: 203–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Hirashima T, Hagiwara T, et al. (2013) Standardization of the Japanese Version of the Sensory Profile: reliability and norms based on a community sample. Seishin Igaku 55: 537–548. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L. (1943) Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child 2: 217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. (1999) The neurobiology of startle. Progress in Neurobiology 59: 107–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane AE, Young RL, Baker AE, et al. (2010) Sensory processing subtypes in autism: association with adaptive behavior. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder 40: 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. (1995) Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, et al. (2000) Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Marco EJ, Hinkley LB, Hill SS, et al. (2011) Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatric Research 69: 48R–54R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EJ, Khatibi K, Hill SS, et al. (2012) Children with autism show reduced somatosensory response: an MEG study. Autism Research 5: 340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki J, Kagitani-Shimono K, Goto T, et al. (2012) Differential responses of primary auditory cortex in autistic spectrum disorder with auditory hypersensitivity. Neuroreport 23: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki J, Kagitani-Shimono K, Sugata H, et al. (2014) Progressively increased M50 responses to repeated sounds in autism spectrum disorder with auditory hypersensitivity: a magnetoencephalographic study. PLoS ONE 9: e102599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor K. (2012) Auditory processing in autism spectrum disorder: a review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 36: 836–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orekhova EV, Tsetlin MM, Butorina AV, et al. (2012) Auditory cortex responses to clicks and sensory modulation difficulties in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). PLoS ONE 7: e39906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz EM, Lane SJ, Sugiyama T, et al. (1993) Startle modulation studies in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 23: 619–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port RG, Anwar AR, Ku M, et al. (2015) Prospective MEG biomarkers in ASD: pre-clinical evidence and clinical promise of electrophysiological signatures. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 88: 25–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds S, Lane SJ. (2008) Diagnostic validity of sensory over-responsivity: a review of the literature and case reports. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 38: 516–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen SA, Miller LJ, Brett-Green BA, et al. (2009) Physiological and behavioral differences in sensory processing: a comparison of children with autism spectrum disorder and sensory modulation disorder. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience 3: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiegler LN, Davis R. (2010) Understanding sound sensitivity in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 25: 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Hashimoto R, Iwase M, et al. (2011) Prepulse inhibition of startle response: recent advances in human studies of psychiatric disease. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience 9: 102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Komatsu S, Nakahachi T, et al. (2016) Relationship of the Acoustic Startle Response and its modulation to emotional and behavioral problems in typical development children and those with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 46: 534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Nakahachi T, Komatsu S, et al. (2014) Hyperreactivity to weak acoustic stimuli and prolonged acoustic startle latency in children with autism spectrum disorders. Molecular Autism 5: 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle CA, Schmidt NL, Goldsmith HH. (2012) Is sensory over-responsivity distinguishable from childhood behavior problems? A phenotypic and genetic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 53: 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1991) Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, WISC III. 3rd ed. New York: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, AUT680497_Lay_Abstract for Relationship between physiological and parent-observed auditory over-responsiveness in children with typical development and those with autism spectrum disorders by Hidetoshi Takahashi, Takayuki Nakahachi, Andrew Stickley, Makoto Ishitobi and Yoko Kamio in Autism

Supplemental material, AUT680497_Supplementary-material for Relationship between physiological and parent-observed auditory over-responsiveness in children with typical development and those with autism spectrum disorders by Hidetoshi Takahashi, Takayuki Nakahachi, Andrew Stickley, Makoto Ishitobi and Yoko Kamio in Autism