Abstract

Background: Photobiomodulation (PBM) therapy is a rapidly growing approach to stimulate healing, reduce pain, increase athletic performance, and improve general wellness. Objective: Applying PBM therapy over the site of a tumor has been considered to be a contraindication. However, since another growing use of PBM therapy is to mitigate the side effects of cancer therapy, this short review seeks to critically examine the evidence of whether PBM therapy is beneficial or harmful in cancer patients. Materials and methods: PubMed and Google Scholar were searched. Results: Although there are a few articles suggesting that PBM therapy can be detrimental in animal models of tumors, there are also many articles that suggest the opposite and that light can directly damage the tumor, can potentiate other cancer therapies, and can stimulate the host immune system. Moreover, there are two clinical trials showing increased survival in cancer patients who received PBM therapy. Conclusions: PBM therapy may have benefits in cancer patients and should be further investigated.

Keywords: : photobiomodulation, low-level laser therapy, cancer, cancer therapy side effects, contraindication, antitumor immune response

Introduction

Photobiomodulation (PBM) is the use of red or near-infrared (NIR) light to heal, restore, and stimulate multiple physiological processes and to repair damage caused by injury or disease. PBM started out as what used to be known as “low-level laser therapy, LLLT” in the late 1960s and was clinically applied for wound healing and the relief of pain and inflammation in a wide range of orthopedic conditions. For many years, it was thought that there was something “special” about lasers and the monochromatic and coherent nature of the light in the laser beam. But, in the 1990s, light emitting diodes (LEDs) were introduced and rapidly gained popularity due to their much lower cost and the absence of safety concerns that were associated with lasers, which previously had led to requirements for “laser safety training courses.”

It is now widely accepted that the noncoherent light from LEDs behaves the same as coherent laser light for most medical applications. In addition, the ability to deliver reasonable power densities (up to 100 mW/cm2) over relatively large areas of the body and to mix different wavelengths together (for instance, red and NIR) are major advantages of LED arrays. An important consideration that applies to many areas of PBM is that of the “biphasic dose–response” or Arndt–Schulz curve.1,2 This principle states that there are optimum parameters (energy density or power density) that provide a benefit to the particular disease, and if these parameters are substantially exceeded, the benefits disappear and can even lead to damaging effects if the dose is extremely high. This phenomenon is also called “hormesis” and has been comprehensively reviewed by Calabrese and Mattson3 and Calabrese and Baldwin.4

PBM and Cancer

Because PBM was shown to stimulate the growth of cancer cells in cell culture studies,5 and can also increase the aggressiveness of some cancer cells,6 some commentators have asserted that PBM may be contraindicated in clinical use in patients with cancer.7 However, not all experimental studies have found the same results. In contrast, it was realized that PBM was highly effective in the mitigation of numerous distressing side effects that occur as a result of a range of different kinds of cancer therapy.8,9

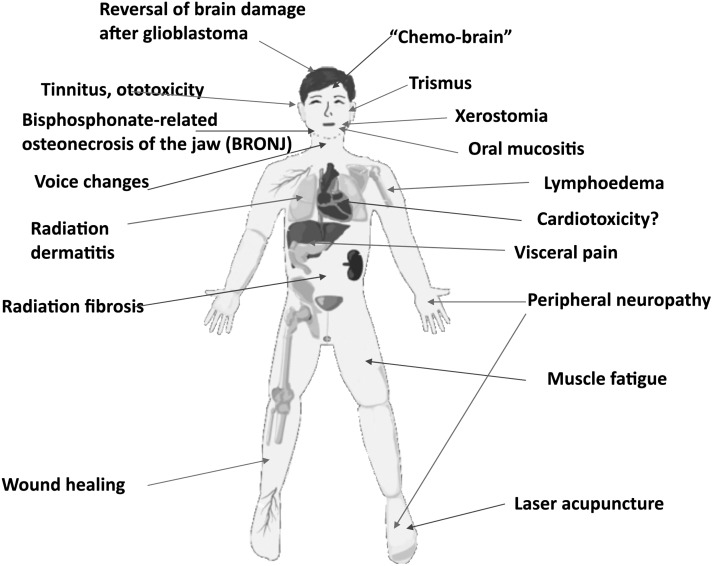

Figure 1 presents a graphical summary of the different kinds of cancer-therapy side effects that could possibly be treated by PBM. These side effects can be so severe that they often lead to the suspension or discontinuation of the cancer therapy with consequent risk to the patient. Perhaps the single most effective indication for PBM (among all known diseases and conditions) is that of oral mucositis.10 Oral mucositis is a common side effect of many kinds of chemotherapy and of radiotherapy for head and neck cancer.11 Other side effects that are under investigation by PBM treatment are chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy,12 radiation dermatitis associated with breast cancer therapy,13 and lymphedema as a result of breast cancer surgery.14

FIG. 1.

Cancer therapy side effects possibly treated by PBM. PBM, photobiomodulation.

Some years ago, when PBM was routinely carried out with laser beams directly applied to the affected tissue region, its use for the mitigation of cancer-therapy side effects was employed with the caveat that the laser should not be used directly over the site of the tumor. However, now that large-area LED arrays and even whole-body light bed systems are becoming more common, the question of whether these devices are safe for a patient with cancer needs to be addressed as pointed out by Sonis et al.15 Moreover, individuals who are using PBM for general health improvement or for increase in athletic performance16 are asking the question: what if I have an undiagnosed malignant or premalignant lesion?

Can PBM Stimulate Cancer?

Despite the existence of numerous studies that have shown that PBM can increase the growth rate of cancer cells in cell culture,17 the number of studies that suggest that PBM can actually exacerbate or stimulate cancer growth in animal tumor models in vivo are relatively few. One study by Frigo et al. compared the effects of PBM (660 nm, 2.5 W/cm2) delivered once a day for 3 days either at a low dose or a high dose in subcutaneous melanoma in mice.18 The low dose (150 J/cm2) reduced the tumor size (not statistically significant), while the high dose (1050 J/cm2) significantly increased the tumor size. However, this study suffered from some problems such as the claim that a C57BL/6 tumor (B16F10) was grown in a nonsyngeneic mouse strain (BALB/c).

Another study from Rhee et al. looked at PBM (650 nm, 100 mW/cm2) as a single dose to an orthotopic mouse model of anaplastic thyroid cancer.19 However, these investigators used an immunodeficient nude mouse model, which does not accurately reflect most human patients. The tumor growth was faster in the PBM groups; HIF-1a and p-Akt were increased, while TGF-b1 expression was decreased.

The third study looked at PBM in the Syrian hamster cheek pouch model of chemical carcinogenesis caused by application of dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA).20 Researchers applied PBM (660 nm, 424 mW/cm2) every other day for 4 weeks starting at end of the cancer induction period (8 weeks of DMBA). More tumors in the PBM group were histologically graded as “poorly differentiated,” and presumably would have a worse prognosis.

Can PBM Directly or Indirectly Attack Cancer?

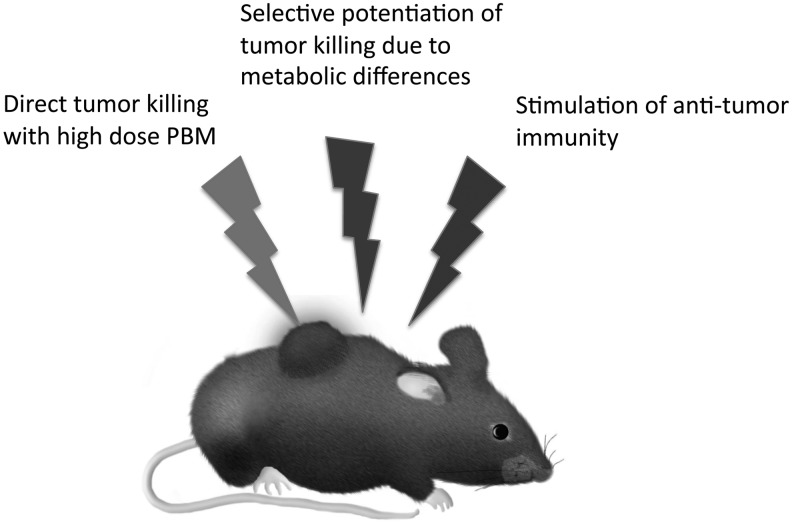

When we consider the possibility that PBM can have a beneficial effect on cancer, it is important to realize that there are three possible ways by which this may happen (Fig. 2). The first involves the direct effect of the light on the tumor cells themselves and may be thought of as a deliberate use of the biphasic dose–response curve to “overdose” the cancer cells.21 This possible methodology has been championed by Da Xing's laboratory in China.22 They call this approach “high fluence low-power laser irradiation, HF-LPLI” and this group often uses a 632 nm HeNe laser delivering 1200 J/cm2 at 500 mW/cm2, over 40 min.23 After publishing several in vitro articles they carried out an in vivo study in BALB/c mice bearing EMT6 breast tumors.24 A single dose of 1200 J/cm2 caused complete regression of tumors, which did not occur in rho-zero EMT6 tumors (lacking functional mitochondria). Moreover, since EMT6 tumors are known to be immunogenic, the mice that were cured of cancer showed some long-term immunological memory.

FIG. 2.

Possible mechanisms by which PBM could be applied against cancer.

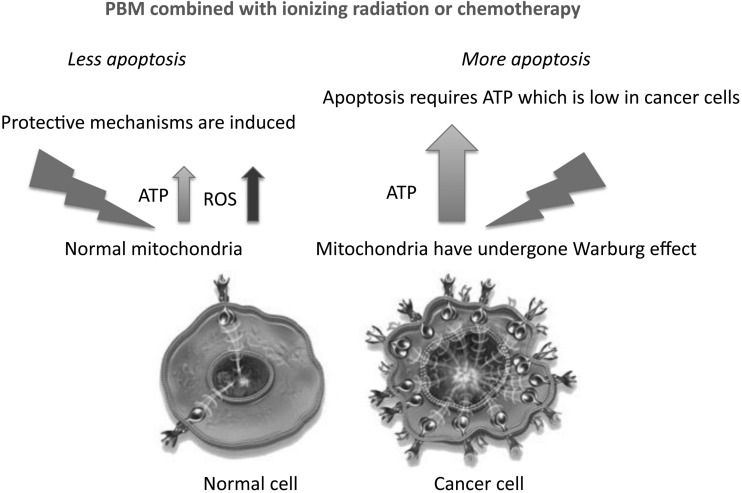

The second method relies on taking advantage of a differential effect of PBM between malignant cancer cells compared to the effects seen on healthy normal cells. This involves combining PBM with an additional cytotoxic anticancer therapy, so that it increases the killing of cancer cells, while at the same time protecting normal healthy cells. While this may appear “too good to be true,” there are some scientific reasons why it may in fact be the case.

These considerations are related to the Warburg effect, by which the mitochondria of cancer cells change their metabolism to carry out aerobic glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation.25 This phenomenon occurs due to the rapid growth of tumor cells outpacing the development of a sufficient blood supply, forcing the cancer cells to become tolerant to chronic hypoxia. Glycolysis consumes much less oxygen than oxidative phosphorylation. The consequences of the Warburg effect are that malignant cells and normal cells may behave very differently in response to PBM. In cancer cells, where adenosine triphosphate (ATP) supply is quite limited, the ATP boost given by PBM may allow the cancer cells to respond to pro-apoptotic cytotoxic stimuli with more efficiently executed cell death (apoptosis) programs, which are heavily energy dependent (i.e., require a lot of ATP26). In contrast, in normal healthy cells that have an adequate supply of ATP, the effect of PBM produces a burst of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that could induce protective mechanisms and reduce the damaging effects of cancer therapy on healthy tissue (Fig. 3). Although this favorable scenario remains a hypothesis at present, there are some published articles that suggest that it could indeed be the case in some anticancer strategies, such as reports that PBM can potentiate the killing of cancer cells by photodynamic therapy27 and also by radiation therapy.28 These researchers have reported that, in theory, PBM increases cell death in cancer cells in response to cytotoxic stimuli. Alternatively, while in normal cells, PBM will exert its protective effect as is well known in the case of neurotoxins, for example.29

FIG. 3.

Mechanisms of selective potentiation of cytotoxicity against cancer cells while preserving normal cells.

The third mechanism, by which PBM could be beneficial to cancer patients, is its possible role in stimulation of the immune system to fight against the cancer. Ottaviani et al.30 showed in a mouse model of melanoma that PBM using three different protocols (660 nm, 50 mW/cm2, 3 J/cm2; 800 or 970 nm, 200 mW/cm2, 6 J/cm2, once a day for 4 days) could all reduce tumor growth and increase the recruitment of immune cells (in particular, T lymphocytes and dendritic cells secreting type I interferons). PBM also reduced the number of highly angiogenic macrophages within the tumor mass and promoted vessel normalization, which is another strategy to control tumor progression.

A recent article from Brazil31 used PBM (660 nm, 100 mW, delivering 35, 107, or 214 J/cm2) to the tumor site thrice every 2 days starting 14 days after rat Walker sarcoma tumor implantation. They measured expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and COX-1, COX-2, iNOS, and eNOS by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in the subcutaneous tumor tissue. Although tumor response was not directly measured, they claimed that the lowest dose (35 J/cm2) produced significant increases in IL-1β, COX-2, and iNOS and significant decreases in IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α and concluded that the 35 J/cm2 “produced cytotoxic effects by generation of ROS causing acute inflammation.”

Is There Evidence of Clinical Efficacy?

A very interesting recent article32 reported that PBM could actually increase treatment outcome and progression-free survival in cancer patients. Ninety-four patients diagnosed with oropharynx, nasopharynx, and hypopharynx cancer were subjected to conventional radiotherapy plus cisplatin every 3 weeks. Preventive PBM was applied to nine points on the oral mucosa daily, from Monday to Friday, and lasted on average 45.7 days. The PBM parameters were 660 nm, 100 mW, 4 J/cm2, and spot size 0.24 cm2. Over a follow-up period of 41 months, patients receiving PBM had a statistically significant better complete response to treatment than those in the placebo group (p = 0.013). Patients subjected to PBM had better progression-free survival than those in the placebo group (p = 0.030) and had a tendency for better overall survival. The mechanism(s) for this effect require more investigation. It could be that the avoidance of oral mucositis led to better nutrition and more complete chemoradiotherapy, while it is also possible that the PBM exerted a direct anticancer effect.

Santana-Blank et al.33 carried out a Phase 1 trial of PBM on 17 patients suffering from a variety of “advanced malignancies.” They used a 904 nm infrared laser, pulsed at 3 MHz, applied using a 2-mm high top hat with a 10-mm beam diameter, and placed at right angles to the surface of the patient's skin in previously determined areas of closest proximity to the biologically closed electric circuits and the vascular interstitial closed circuit that would most efficiently carry the laser energy to the target tissues.33 This approach was first described by Nordenstrom34 who inserted wires through the thoracic wall to reach pulmonary tumors and circulated electric current. Patients were given a laser device to use at home each day and were allowed to remain in the trial as long as possible.

In addition to evaluation by the attending physicians, the patients were asked to keep a journal over the length of their time in the trial and to record the time and duration of each PBM application, as well as any sign, symptom, or problem/side effect experienced. No dose-limiting toxicity was observed. Five patients reported occasional headaches (grade 2), and four referred local pain (grade 2). Statistically significant increases in Karnofsky performance status and quality of life (QLI) were observed in all of the follow-up intervals compared with pretreatment values. In the six surviving patients, one patient had a complete response, one partial response, four stable disease >12 months, and one progressive disease. In the patients that died during the trial, significant increases in QLI were observed during the first two intervals. Eight patients had stable disease >6 months and two had progressive disease. The overall response rate was 88.23% in these terminally ill (late stage) patients.

Analysis of the peripheral blood leukocytes showed an initial increase in TNF-α followed by a decrease in survivors and a progressive and constant increase in TNF-α levels and an increase in serum levels of sIL-2R in those who died.35 The mechanisms operating in this clinical study require more investigation, but if it can be repeated, it could be very promising.

Finally, Russian investigators have reported use of PBM in cancer patients, but it is difficult to retrieve details of the studies.36,37

Conclusions and Unanswered Questions

PBM is becoming a well-established approach to mitigate or prevent the development of cancer therapy associated side effects, especially oral mucositis. The more intriguing question is not merely whether PBM is safe and effective in cancer patients, but whether PBM can play an active role in cancer treatment? There are tantalizing reports that this may indeed be the case, but there are many questions still to be answered. The wide array of different devices and parameters that have been used make this quite a complicated area.

While the biphasic dose–response is accepted in normal tissue, how it applies to malignant tissue is unclear. In some cases, it appears that a very high dose will create a cytotoxic level of ROS that can directly destroy the tumor. In other cases, the main effect of PBM appears to stimulate the immune system, and a low dose may be more effective. If the aim is to stimulate the immune system, then it is best to directly irradiate the tumor or to direct the light to the bone marrow, the lymphatic organs, or even the whole body? What can be concluded is that now is perhaps the time to lose the fear of exacerbating cancer by shining light on it and start to plan well-controlled clinical trials, even if these must necessarily be in advanced patients who have run out of options. There is clearly a great number of new possibilities involving the combination of PBM with other forms of cancer therapy, which may allow us to take advantage of biochemical differences between cancer and normal cells to effectively work against the cancer.

Acknowledgments

M.R.H. was funded by U.S. NIH grant R01AI050875.

Author Disclosure Statement

S.T.N. and J.R.S. are co-owners of JOOVV, Inc., a company selling light therapy devices. M.R.H. is on the scientific advisory board of JOOVV, Inc.

References

- 1.Huang YY, Chen AC, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy. Dose Response 2009;7:358–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang YY, Sharma SK, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy—an update. Dose Response 2011;9:602–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calabrese EJ, Mattson MP. How does hormesis impact biology, toxicology, and medicine? NPJ Aging Mech Dis 2017;3:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calabrese EJ, Baldwin LA. Hormesis: a generalizable and unifying hypothesis. Crit Rev Toxicol 2001;31:353–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sroka R, Schaffer M, Fuchs C, et al. Effects on the mitosis of normal and tumor cells induced by light treatment of different wavelengths. Lasers Surg Med 1999;25:263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperandio FF, Giudice FS, Correa L, Pinto DS, Jr, Hamblin MR, de Sousa SC. Low-level laser therapy can produce increased aggressiveness of dysplastic and oral cancer cell lines by modulation of Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. J Biophotonics 2013;6:839–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navratil L, Kymplova J. Contraindications in noninvasive laser therapy: truth and fiction. J Clin Laser Med Surg 2002;20:341–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zecha JA, Raber-Durlacher JE, Nair RG, et al. Low-level laser therapy/photobiomodulation in the management of side effects of chemoradiation therapy in head and neck cancer: part 2: proposed applications and treatment protocols. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2793–2805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zecha JA, Raber-Durlacher JE, Nair RG, et al. Low level laser therapy/photobiomodulation in the management of side effects of chemoradiation therapy in head and neck cancer: part 1: mechanisms of action, dosimetric, and safety considerations. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2781–2792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissheimer C, Curra M, Gregianin LJ, et al. New photobiomodulation protocol prevents oral mucositis in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients-a retrospective study. Lasers Med Sci 2017;32:2013–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maria OM, Eliopoulos N, Muanza T. Radiation-induced oral mucositis. Front Oncol 2017;7:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Argenta PA, Ballman KV, Geller MA, et al. The effect of photobiomodulation on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, sham-controlled clinical trial. Gynecol Oncol 2017;144:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strouthos I, Chatzikonstantinou G, Tselis N, et al. Photobiomodulation therapy for the management of radiation-induced dermatitis: a single-institution experience of adjuvant radiotherapy in breast cancer patients after breast conserving surgery. Strahlenther Onkol 2017;193:491–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lima MT, Lima JG, de Andrade MF, Bergmann A. Low-level laser therapy in secondary lymphedema after breast cancer: systematic review. Lasers Med Sci 2014;29:1289–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonis ST, Hashemi S, Epstein JB, Nair RG, Rabler-Duracher JE. Could the biological robustness of low level laser therapy (Photobiomodulation) impact its use in the management of mucositis in head and neck cancer patients. Oral Oncol 2016;54:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferraresi C, Huang YY, Hamblin MR. Photobiomodulation in human muscle tissue: an advantage in sports performance? J Biophotonics 2016;9:1273–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AlGhamdi KM, Kumar A, Moussa NA. Low-level laser therapy: a useful technique for enhancing the proliferation of various cultured cells. Lasers Med Sci 2012;27:237–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frigo L, Luppi JS, Favero GM, et al. The effect of low-level laser irradiation (In-Ga-Al-AsP-660 nm) on melanoma in vitro and in vivo. BMC Cancer 2009;9:404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhee YH, Moon JH, Choi SH, Ahn JC. Low-level laser therapy promoted aggressive proliferation and angiogenesis through decreasing of transforming growth factor-beta1 and increasing of Akt/hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Photomed Laser Surg 2016;34:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de C Monteiro JS, Pinheiro AN, de Oliveira SC, et al. Influence of laser phototherapy (lambda660 nm) on the outcome of oral chemical carcinogenesis on the hamster cheek pouch model: histological study. Photomed Laser Surg 2011;29:741–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiro NE, Hamblin MR, Abrahamse H. Photobiomodulation of breast and cervical cancer stem cells using low-intensity laser irradiation. Tumour Biol 2017;39:1010428317706913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu S, Xing D, Gao X, Chen WR. High fluence low-power laser irradiation induces mitochondrial permeability transition mediated by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Physiol 2009;218:603–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu S, Zhou F, Wei Y, Chen WR, Chen Q, Xing D. Cancer phototherapy via selective photoinactivation of respiratory chain oxidase to trigger a fatal superoxide anion burst. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20:733–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu C, Zhou F, Wu S, Liu L, Xing D. Phototherapy-induced antitumor immunity: long-term tumor suppression effects via photoinactivation of respiratory chain oxidase-triggered superoxide anion burst. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016;24:249–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalyanaraman B. Teaching the basics of cancer metabolism: developing antitumor strategies by exploiting the differences between normal and cancer cell metabolism. Redox Biol 2017;12:833–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eguchi Y, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y. Intracellular ATP levels determine cell death fate by apoptosis or necrosis. Cancer Res 1997;57:1835–1840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsai SR, Yin R, Huang YY, Sheu BC, Lee SC, Hamblin MR. Low-level light therapy potentiates npe6-mediated photodynamic therapy in a human osteosarcoma cell line via increased ATP. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2015;12:123–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djavid GE, Bigdeli B, Goliaei B, Nikoofar A, Hamblin MR. Photobiomodulation leads to enhanced radiosensitivity through induction of apoptosis and autophagy in human cervical cancer cells. J Biophotonics 2017. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1002/jbio.201700004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong-Riley MT, Liang HL, Eells JT, et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: role of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem 2005;280:4761–4771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ottaviani G, Martinelli V, Rupel K, et al. Laser therapy inhibits tumor growth in mice by promoting immune surveillance and vessel normalization. EBioMedicine 2016;11:165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrellis MC, Frigo L, Marcos RL, et al. Laser photobiomodulation of pro-inflammatory mediators on Walker Tumor 256 induced rats. J Photochem Photobiol B 2017;177:69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antunes HS, Herchenhorn D, Small IA, et al. Long-term survival of a randomized phase III trial of head and neck cancer patients receiving concurrent chemoradiation therapy with or without low-level laser therapy (LLLT) to prevent oral mucositis. Oral Oncol 2017;71:11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santana-Blank LA, Rodriguez-Santana E, Vargas F, et al. Phase I trial of an infrared pulsed laser device in patients with advanced neoplasias. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:3082–3091 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nordenstrom BE. Fleischner lecture. Biokinetic impacts on structure and imaging of the lung: the concept of biologically closed electric circuits. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1985;145:447–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santana-Blank LA, Castes M, Rojas ME, Vargas F, Scott-Algara D. Evaluation of serum levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R) and CD4, CD8 and natural killer (NK) populations during infrared pulsed laser device (IPLD) treatment. Clin Exp Immunol 1992;90:43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhevago NA, Samoilova KA, Davydova NI, et al. [The efficacy of polychromatic visible and infrared radiation used for the postoperative immunological rehabilitation of patients with breast cancer]. Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kult 2012;4:23–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimin AA, Zhevago NA, Buiniakova AI, Samoilova KA. [Application of low-power visible and near infrared radiation in clinical oncology]. Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kult 2009;6:49–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]