Abstract

Purpose of the Study

To identify and examine the published qualitative research evidence relative to the experience of living with dementia.

Design and Methods

Metasynthesis was used as the methodological framework to guide data collection and analysis.

Results

Three themes were identified. The first theme considered the main condition-related changes experienced by people with dementia (PWD) and showed how these are interlinked and impact upon various areas of people’s lives. The second theme indicated that amidst these changes, PWD strive to maintain continuity in their lives by employing various resources and coping strategies. The third theme underlined the role of contextual factors. The reviewed evidence indicates that, the emerging experience of PWD and their potential to adjust to the continuous changes is influenced by access to and quality of both personal and contextual resources which remain in a constant, transactional relationship to each other.

Implications

The findings were interpreted and discussed in the context of relevant theoretical frameworks and research evidence. It was considered that current evidence and findings presented in this review can be further explored and expanded upon in a more systematic way through research conducted within the theoretical framework of dynamic systems theory. Further research would be also beneficial to explore the subjective experience of dementia from a participatory perspective. Exploring the application of these theoretical standpoints would contribute to the current state of knowledge and offer both PWD and carers fresh perspective on the nature of change and potential for adaptability in dementia.

Keywords: Dementia, Lived experience, Qualitative research methods

Dementia is the leading cause of disability amongst older people and constitutes one of the greatest challenges currently facing health and social care services worldwide (World Health Organization, 2012). Rapidly growing prevalence and socioeconomic costs of dementia have been well documented (Alzheimer Disease International, 2009, 2015) and concern governments internationally (UK Government, 2013). Human cost of dementia has also been recognized; with many countries undertaking strategic efforts to address challenges related to the condition (Alzheimer Disease International, 2012). These global drivers for change demonstrate that world leaders are committed to explore innovative frameworks and approaches to improve treatment outcomes and the experience of people with dementia (PWD) and their carers.

The way certain conditions and phenomena are understood and conceptualized, shape professional approaches to treatment and sociocultural perceptions of those experiencing them (Innes & Manthorpe, 2012). This in turn has implications in terms of the experience of individuals living with a condition. Historically different approaches to understanding dementia informed different perspectives about living with the disease. The two dominant models, biomedical and bio-psycho-social, although indisputable in their contributions to understanding dementia and guiding care efforts, have been recently critiqued as incomplete and limiting in terms of clinical utility (Spector & Orrell, 2010).

Significantly, it was identified that these models fail to fully recognize the potential for adaptability and do not offer a framework for comprehensive conceptualization of needs and resources to support clinical practice (Spector & Orrell, 2010). Moreover, the impact that dementia has on people’s ability to participate in daily activities and its relationship to health and wellbeing, although documented within the literature (Wicklund, Johnson, Rademaker, Weitner, & Weintraub, 2007), has tended to be overlooked or underestimated. Furthermore, it has been highlighted that the existing models reflect the longstanding nature of public and academic debate about the condition, which has been dominated by knowledge based on professional expertise, rather than that routed in personal experiences (Bartlett & O’Connor, 2010).

Recently it has been argued that to foster a more comprehensive, multifaceted picture of dementia with the view of informing innovative conceptual frameworks and approaches to care, our conceptualizations of the condition must include evidence derived from personal stories (Bartlett & O’Connor, 2010). This, combined with the rising status of evidence based on qualitative research, fueled by the desire by government agencies and professional bodies to inform policy by subjective accounts of illness, results in more research being published in relation to firsthand experience of dementia.

Hence, it appears timely to take stock of how people make sense of being diagnosed and living with the condition and consider how dementia affects individuals and their response to this experience, based on first hand reports. Previous reviews of the available evidence focused on participants’ experiences of living with early stage dementia (Steeman, Casterlé, Dierckx, Godderis, & Grypdonck, 2006); highlighted strategies used to deal with dementia related challenges (de Boer, Hertogh, Dröes, Riphagen, Jonker, & Eefsting, 2007); considered impact of dementia on self and identity (Caddell & Clare, 2010); and identified factors that shape people’s experiences of the process of dementia diagnosis and treatment (Bunn et al., 2012). None of these reviews consider relationships between the various factors that determine people’s experience and potential for adaptation to living with dementia. Neither do they examine evidence related directly to participation and the impact it has on people’s health and wellbeing.

Therefore, the purpose of this review is to methodically synthesize the existing qualitative research evidence focused on the firsthand experience of living with dementia, with the specific focus on relationships between factors affecting peoples’ experience and issues relating to participation and adaptation. It is anticipated that this will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of dementia and the impact it has on individuals.

Method

Meta-synthesis is a systematic method of synthesizing findings from multiple qualitative studies focused on a common topic; aiming to construct adequate interpretive explanations of these findings (Barroso & Powell-Cope, 2000). This paper presents the results of a meta-synthesis reflecting components of the process proposed by Finfgeld (2003). Hence, in order to meet the study objectives, all studies selected through the systematic review of the literature were examined by asking the following research questions:

What philosophical and theoretical perspectives are reflected in the current state of knowledge regarding dementia experience?

What is the methodological status of the included studies?

What are the key themes emerging from the included studies?

The specific procedures applied in the meta-synthesis involved steps outlined by Sandelowski and Barroso (2003) and are presented in the section below.

Procedures

Exploration of the literature involved systematic searches of the following electronic databases: Abstracts in Social Gerontology, ASSIA, CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PsycINFO, and Social Sciences Citation Index. The following key terms were used across all databases: [“Dementia OR Alzheimer”s disease”] AND [“experience,” “attributions,” “beliefs,” “concepts,” “knowledge,” “lived experience,” “life experience,” “meaning,” “narrative,” “perceptions,” “perspectives,” “representations,” “understanding,” “outcomes,” “schema,” “values” OR “quality of life”]. MeSH headings, free text searching, Boolean operators and truncations were used to expand the literature search. Records were downloaded into Reference Manager® software and screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|

| Inclusion | Population: samples where the majority of participants were community dwelling older adults (≥65) with a diagnosis of dementia. |

| Main focus: meaning/experience of dementia; both self-reported and proxy reports. | |

| Methodology: qualitative, interpretative studies. | |

| Language: English. | |

| Timeframes: January 1990 to September 2015. | |

| Exclusion | Population: other age groups (<65) and samples including people with diagnostic categories other than dementia (e.g., mild cognitive impairment, cancer); samples where the majority of participants were people living in residential care. |

| Main focus: | |

| Studies of the “illness experience” where dementia is included, but is not the main topic of the study and where other co-morbidities may strongly contribute to the experience under scrutiny. | |

| Studies which focus on a specific aspect of dementia experience out of the scope of this review (e.g., the meaning of living alone and temporality in dementia). | |

| Studies reporting experience of particular rehabilitative approaches by PWD or carers. | |

| Studies reporting evaluation of specific therapeutic approaches. | |

| Studies reporting carers’ own experience related to their caring role. | |

| Methodology: quantitative methodologies, opinion pieces, theoretical articles unless based on primary research. | |

| Language: studies published in a language other than English. | |

| Timeframes: literature published prior to 1990, unless cited as a key article on the topic. | |

| No abstract available for review. | |

Each study was systematically reviewed to identify country and dominant discipline, sample characteristics, and features of methodology; which were tabulated to facilitate data analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The quality of evidence offered by each of the included studies was evaluated against a hierarchy of evidence specific to qualitative methods (Daly et al., 2007) (Supplementary Table 2). Synthesis of findings was informed by analytical strategies proposed by Sandelowski and Barroso (2003). Firstly, taxonomic analysis was completed to identify significant underlying concepts and conceptual relationships. This was followed by a systematic search for similarities, differences, and patterns of relationships within findings reported in the included studies, a process referred to as sustained comparisons. In parallel to these activities, we compared the conceptual synthesis offered within individual studies to determine how these could be integrated to inform our meta-synthesis. Finally, in the discussion, we place the findings of our meta-synthesis in the context of wider literature related to the identified themes.

Results

Included Studies

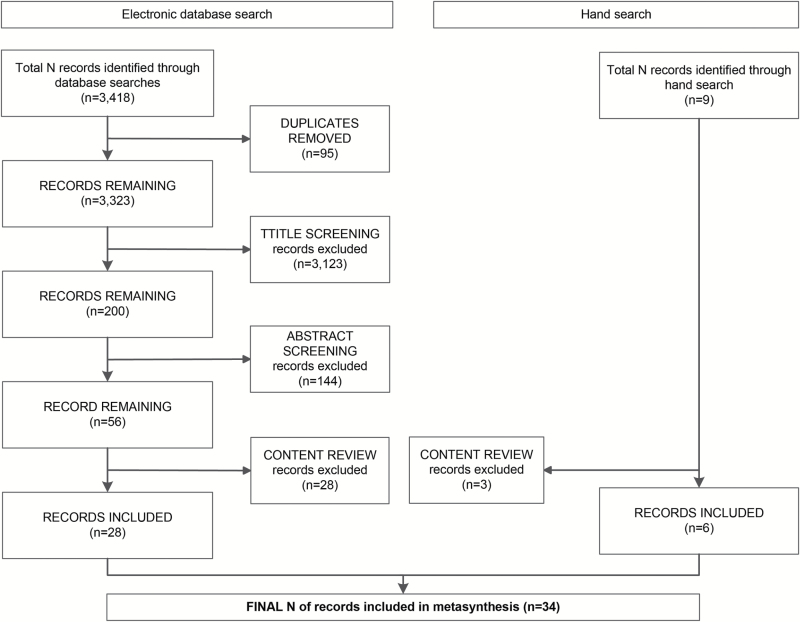

In total 3,418 records were retrieved through searches of electronic databases. These were subject to a systematic review which followed the process outlined in Figure 1. A further nine articles were identified through hand searches; contents of these were scrutinized against inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study selection process resulted in the final 34 articles being included for meta-synthesis.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow chart.

The included studies were completed in various countries including United Kingdom (N = 11), Canada (N = 7), Sweden (N = 5), United States (N = 4), Australia (N = 2), Belgium (N = 2), China (Hong Kong) (N = 1), Iran (N = 1), and New Zealand (N = 1). Authors represented various professional perspectives including nursing (N = 16 studies), psychology (N = 8), sociology (N = 4), occupational therapy/ occupational science (N = 3), social work (N = 2), and psychiatry (N = 1).

Of 34 studies, 16 did not report a specific philosophical or theoretical perspective applied to guide the enquiry. Where a theoretical stance was reported, authors indicated phenomenology (N = 6), grounded theory (N = 2), social constructionism (N = 1) or other theoretical frameworks (N = 9) as guiding their research. Purposive sampling was the most commonly utilized sampling strategy with semi-structured interviews being the predominant method of data collection and phenomenological content analysis a favored data analysis method. When considered against the hierarchy of evidence classification system (Daly et al., 2007) only two articles met the criteria outlined for the highest quality studies (Level I).

Sample size was reported in all 34 articles, amounting to a total of 626 participants (range: 1–143; μ = 19.56) across all independent samples. Samples of 28 studies consisted of PWD only (N = 487), whereas the remaining six studies also included caregivers as joint study participants (N = 139).

Supplementary Table 3 details methodology and sample characteristics of the included studies.

Key Themes

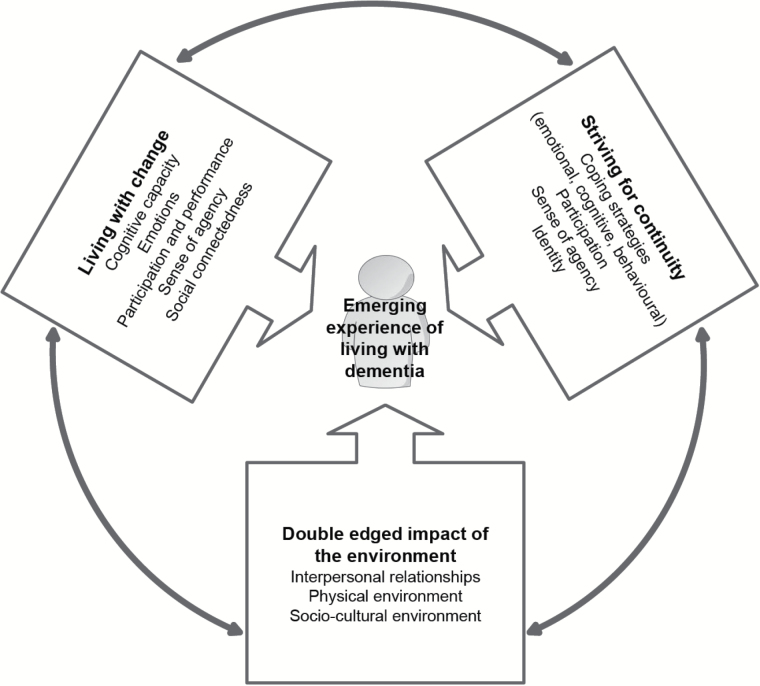

The majority of the included articles reported matters related to dementia experience in a descriptive manner, listing and exploring factors which, according to participants, impacted upon their experience. However, there was a substantial proportion of studies (N = 16) which indicated that PWD appear to live in a state of “flux” (Caddell & Clare, 2011), characterized by tension between continuous change and their desire for and efforts to maintain continuity. A number of studies also referred to environmental factors and their role in shaping people’s experience of living with dementia. As a result, three overarching themes: (a) Living with change, (b) Striving for continuity, and (c) Double edged impact of the environment; were identified and are presented below.

Each of the main themes incorporates a number of sub-themes representing constituting factors. Based on the findings from the included studies we consider the three main themes identified in this metasynthesis and underlying constructs as being in dynamic, transactional relationships with each other; and the experience of PWD as continuously emerging from these relationships (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Experience of living with dementia: transactional relationships between identified themes.

The reviewed evidence shows that, amidst the continuous changes, PWD strive to maintain continuity in their lives. However, it appears that the emerging experience of PWD is influenced by condition related changes (Theme 1) and access to and quality of both personal and contextual resources. The personal factors influencing PWD effectiveness in maintaining continuity are presented in Theme 2. Contextual factors are considered in Theme 3.

Table 2 provides a sample of quotations extracted from the individual studies, linking them to the main themes and sub-themes.

Table 2.

Quotations, Themes, and Concepts From Primary Studies and Their Relation to the Synthesized Themes

| Theme/subtheme | Data | |

|---|---|---|

| Living with change | ||

| Cognitive capacity | “I have read that you know as people get older the memory tends to fade a bit and like a lot of people, I can remember things from way past, but I have difficulty in remembering what I did yesterday, you see.” (Gillies, 2000) | |

| “I suddenly realize that she asked me to do something and I haven’t remembered to do either of the two things. That frustrates her a bit too, of course.” (Gilmour & Huntington, 2005) | ||

| “I have dementia and I’m going to reach a stage whereby I can no longer think as a logical person or do things in a logical way.” (Harman & Clare, 2006) | ||

| “Like leaves fall to the ground from a tree, old people lose their memories.” (Langdon et al., 2007) | ||

| “You tell them that my memory has gone, that’s a symbol for it, but it’s not just my memory that’s gone, it’s the comprehension that’s gone…” (Lawrence et al., 2011) | ||

| “I can look up somebody’s name, go to the phone book, once I’ve got the number, I’ve forgotten whose name I’m looking for.” (MacQuarrie, 2005) | ||

| “… [It] is a teasing disease. It teases you a lot. For example, you no longer recognise your childhood classmates. Your friends’ faces look strange. It’s like typhus—it breaks you down./…/It is very troublesome; it’s very bad.” (Mazaheri et al., 2013) | ||

| “I don’t have the ability to grasp and understand things the way I did years ago. I don’t remember. That’s my whole problem is my memory” (Phinney, 1998) | ||

| “What I find difficult though, is remembering uh, remembering things. Maybe peoples’ names, or what I did […]” (Phinney & Chesla, 2003) | ||

| “That’s what puzzles me sometimes…. I can go back to when I was about seven years old… But something that happened, like. Like when you’ve gone, if somebody rang me and said what have you been doing today, I might say I don’t know. I could have forgotten.” (Preston et al., 2007) | ||

| “Actually, I don’t think I really realized at the beginning that I had memory loss. I’d say, ‘I can’t think of it right now,’ if somebody asked me something, and I didn’t realize I had memory loss.” (Werezak & Stewart, 2009) | ||

| Emotions | “I think the whole class of problems that Alzheimer’s disease belongs to are the most frightening name you could find in the language, I think… dementia… Because when I was a youngster, the whole of society didn’t refer to that group of, ah, diseases by any particular name at all… and as they’re aware, it came from, you know, the adjective from that is demented and a demented person is a loony and a loony is somebody you put in… an asylum… Now I’ve got this strongly in my mind… that I am being told in the gentlest of ways that I may be suffering from early dementia in one form or another and I… I still can’t… disconnect… that word from the asylum…” (Gilmour & Huntington, 2005) | |

| “I was devastated, in shock, speechless. I could not believe that I could have AD… I was angry, depressed, felt suicidal, and hated the world. After experiencing this myriad of emotions, I calmed down and realised that there is still a world out there for me to participate in.” (Macrae, 2008) | ||

| “First senses are no. No way. I don’t have such a thing! You know? I mean this is how your first reaction is. I’m just tired. I’ve had a bad day. Or something that really upset me very much about the same time when I started. I mean it was just one of those things. No. I don’t. That’s not me. I didn’t! I don’t want that! You know as if you could just go up and brush it aside. Because anybody that knows the word, I think they know what it is, but you deny it!” (MacQuarrie, 2005) | ||

| “…like you are totally in a foreign land, and nothing is known to you. But at the same time you know you are supposed to know . . . like looking for something that just isn’t there. Empty, lonely, isolated. But you keep looking for something familiar, that you know is there, but you just can’t see it.” (Parsons-Suhl et al., 2008) | ||

| “I think maybe I could probably handle somebody telling me I had whatever, but when it’s your mind it’s just really devastating, because you think, oh, how long is it going to be until I’m going to be a burden? That’s one of the first things you think of…like, how long is it going to be before I’m a…I’m not able to look after myself and I have to have [my husband] doing everything for me.” (Werezak & Stewart, 2009) | ||

| Participation and performance | “Well, as my memory’s got worse and worse, erm… I’ve - I’ve become less and less involved in things going on.” (Caddell & Clare, 2011) | |

| “In my whole life I have been active in many choirs. Now, when I no longer remember the songs, I have decided to give up that activity . . . not funny to do things bad when you have been a “master”.” (Holst & Hallberg, 2003) | ||

| “Because before I used to do everything for myself, go out, go to help people and do different things you know, around. I did everything for myself. But now I can’t do anything, I always forgetting you see.” (Lawrence et al., 2011) | ||

| “I can’t get out and about for myself.” (Moyle et al., 2011) | ||

| “I cannot count you see. I choose not to count. […] when I’m knitting, I have to count and count and count and count to get it right. What has been there before has gone.” (Öhman & Nygård, 2005) | ||

| “I quit teaching, basically, because I was having problems remembering and I didn’t keep up,… I didn’t keep up my, uh… it was just a matter of remembering names at the particular time” (Ostwald et al., 2002) | ||

| “I used to be able to talk to you, write orders out, and listen to someone else… but that, I’ve lost. That’s a definite loss… I’m not what I was 20 years ago. I can’t really, really (3 second pause) I really can’t do things that I would like to do. It’s just not there anymore.” (Phinney et al., 2013) | ||

| Sense of agency | “I feel more settled and okay in myself. That I’m still doing things and capable. To have still some independence in there. That I am still here, and I do have a say, and I’m not just a person with dementia and ignored, and that everybody else knows more than me. To still understand that there is a person there, and being aware of what stage I’m at, and what I can still input and allow that to happen.” (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013) | |

| “Because she wants to make things so easy for me, she got into all my records, you know, business records, because one of the people who… talked to us said we needed to have some of those things. But nobody asked me for them and I happened to be cleaning up something on the table and found some of these records that were important to me. And so I said, ‘Don’t, don’t take anything out until you ask me about it. Just leave them there because this is going to go on a long time and we’ll have plenty of time to do these.’ But, she, I don’t know, I got scared because I thought maybe she lost something.” (Ostwald et al., 2002) | ||

| Social connectedness | “I can’t manage it anymore so it’s okay. It’s a pity though that you lose contact with so many nice people.” (Holst & Hallberg, 2003) | |

| “I sometimes find it difficult to express myself, I cannot find the words, and therefore I avoid talking to others.” (Holst & Hallberg, 2003) | ||

| “I am bad… at talking properly… maybe it follows with the disease… before I used to talk and got it out what I wanted to say but… now it is irritating… it does not sound good what I am saying…” (Karlsson et al., 2014) | ||

| “… I avoid going to people, especially former friends, unless I go to places where everyone has Alzheimer’s.” (Lawrence et al., 2011) | ||

| “But I seem like I’m quite content to, if I stay at home, or stuff like that where I don’t have to think too fast, or not just fast, but correctly, if you know what I am saying” (Ostwald et al., 2002) | ||

| “Everybody is affected by it. And uh to me [pause] it barks sometimes because people answer me short. They don’t realize that some of the things I’m trying to say I can’t say right… they don’t realize that I am trying to say something serious… [pause] So that it makes it hard for the family. They are suffering like I am” (Phinney & Chesla, 2003) | ||

| “I do not have that many acquaintances anymore. Somehow, I sit here like a crow in her nest . . .” (Vikström et al., 2008) | ||

| Striving for continuity | ||

| Coping strategies | “I must be one of the victims; I’ve got a chance of being one of the contributors. I feel quite good about that.” (Clare, 2002) | |

| “I think the coming to terms with the matter is, um, well it has to happen… Still in the middle of that process, I think.” (Clare, 2002) | ||

| “Well, I just accept things as they are. I don’t see what else you can do.” (Gillies, 2000) | ||

| “. . . Appointments . . . I try to write everything down in my diary and look at it. If I remember to look at it.” (Gillies, 2000) | ||

| “If the wife’s there we get on alright. She understands that. She’s more or less my memory.” (Gillies, 2000) | ||

| “You can fight it or try to overcome it or step around it, but it’s there and it’s not as if you can say that ‘what a nuisance, I’ll push it aside and carry on […]. It is a different way of life. And you can roll with it or I suppose you could go and hibernate, uh, tuck yourself away, but yes, it does make a difference.” (Hulko, 2009) | ||

| “Eventually you just have to tell your friends, ‘Sorry, I’ve been having some memory problems lately” (MacQuarrie, 2005) | ||

| “For me, surviving is both attitude and action. It means that even while knowing that I have this disease, I can still go on with life always doing the best I can with what I have at any given point. This is the attitude of seeing life worth living.” (Macrae, 2008) | ||

| “I make everybody laugh . . . well, that’s the only thing left for us. We’ve already lost our memory . . . if you haven’t got a sense of humour, you’re dead.” (Menne et al., 2002) | ||

| “Although I am very forgetful now, I try to keep my usual routine, do exercise and read newspapers.” (Mok et al., 2007) | ||

| “There is not a great deal of problem because I would not attempt to do those types of jobs now” (Pearce et al., 2002) | ||

| “It’s just old age” (Phinney et al., 2002) | ||

| “[…] my husband does the cooking and I don’t like that part. Interviewer: You miss doing cooking? Yeah, I do. And I think, well sure I could do the cooking. And I think, well maybe I’ll do the vegetables. Yeah.” (Stieber-Roger, 2008) | ||

| “I think I am very fortunate. I have really managed to accept it and to say that I’m a lot luckier than a lot of other people. I could be a lot worse. […]” (Werezak & Stewart, 2009) | ||

| Participation | “Well… life is fine but… I know that I am annoying my wife a bit because… I’m like a child I suppose… I do not know what I shall occupy myself with… so now and then I get on the bike for a while so she can have some respite…” (Karlsson et al., 2014) | |

| “Through this period of AD, I have changed significantly. I understand people a lot more. I am more mellow than I have ever been… I really find lots of things to do and ways to help people. So this is me now… I am kinder, gentler, and… Until that time, I’m getting out and doing things, always!” (Macrae, 2008) | ||

| “She has said to me since she has moved here, ‘sometimes I get a bit lonely but there is always plenty to do’, I think her formula is if you feel a bit lonely then you had better get busy doing something.” (Female carer) (Moyle et al., 2011) | ||

| “Oh, missing out on a lot [laughs]. Right. I don’t like the idea of not doing, doing things and enjoying things. That’s the big [pause] And when I’m not, I don’t think I would want to live. Why exist if you don’t enjoy doing things?” (Phinney & Chesla, 2003) | ||

| “You gotta do something, especially if you’ve spent your whole life working with your hands, you couldn’t just walk away and leave it” (Phinney et al., 2013) | ||

| “I can’t complain, because I can still do some things… I can’t work anymore as I used to, but I still take care of my dinner and so forth. And I still help with the cleaning. Light chores, nothing too heavy. And my son does everything else” (Steeman et al., 2007) | ||

| “Being with people, I love being with people. I love being with organisations and I like to attend festivals and so on. To see it and to enjoy it. I have always been very active.” (Steeman et al., 2013) | ||

| “I still work for a firm in N. and now and then I still play a little bit the role of consultant, adviser. And as soon as J., that is how they call the big boss over there, will say that he no longer needs me, I’ll be in big distress. You know, being written off.” (Steeman et al., 2013) | ||

| “ […] I still can do my [lay ministry work], I still can see my kids, I can still do things that I like doing, and I think you have to sometimes just be grateful for what you have.” (Werezak & Stewart, 2009) | ||

| Sense of agency | “I feel like I’m part of the decision, even though I know probably now I’m not contributing a great deal, at least I feel as if I’m part of the decision. And that’s very, very important. So I feel enabled and empowered, even though each year goes by I’m less participating, at least I feel as if I am.” (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013) | |

| “I’m trying to control it. Trying to improve on things that I forget about” (Gillies, 2000) | ||

| “No one else can fix my future” (Karlsson et al., 2014) | ||

| “No! No! That irked, that irked me! Oh, I was furious! It wasn’t the idea of what they did. It was not to have talked to me too! You know like, say to me, we think this is the best for you, and we will look after you.” (MacQuarrie, 2005) | ||

| “As long as I can do something safely and do it properly, then I don’t want to have to depend on somebody else. Because you feel useless then and I don’t want to be useless.” (Menne et al., 2002) | ||

| Identity | “I’m still the same silly bugger.” (Caddell & Clare, 2011) | |

| “No, I don’t think so, I don’t think I’ll ever change.” (Caddell & Clare, 2011) | ||

| “I’m still the same person, I’m probably, I don’t mean to say less of a person, but I’m probably 90 percent of the person I was.” [What’s the 10 per cent that has changed?]. “Well, I’m not as handy as I was you know.’ (Macrae, 2008) | ||

| “…and when I go there, I go to be a woman. It’s the women’s group. It’s not like when I go to the memory club to be, um, well to be with other people with Alzheimer’s. Which is good for me as well. I go there as someone who has Alzheimer’s if you, um (pause). It’s the different bits of me at these places, um [pause]. It’s all me, but I’m being most conscious of the woman bit with the women and the Alzheimer’s bit at the club” (Preston et al., 2007) | ||

| “Maybe it’s important that, although you have a memory loss, you haven’t lost your mind completely, you know…. You’ve lost your memory but you haven’t lost your mind. And you’re still the same person, and you do make mistakes when you’re…when you repeat yourself, but you’re still knowledgeable, you’re still the same person, and I think it’s important that people realize that you don’t change. I mean, things…your life changes, of course, but you’re still the same person inside…at least I think I am. [laughs]” (Werezak & Stewart, 2009) | ||

| Double edged nature of the environment | ||

| Enabling | Disempowering | |

| Interpersonal relationships | “My daughters didn’t take over, and they didn’t just assume that ‘Mum can’t do this anymore’. They sort of, just wanted to see where I was comfortable in how much stuff I did want, and what I was capable of doing myself… They allowed me to still say, ‘Yes this is okay, and this is what I’m comfortable with and yes, I can still do this’ and it worked out really well.” (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013) | “Walks, yeah. I used to walk for miles, but me family don’t want us to go away far, you know, but -…Well the family really, they’re frightened, you know, but I’m not, I’m not...” (Brittain et al., 2010) |

| “When the guy [from the agency] came out he basically didn’t talk to me, he was talking to [my wife]. And I got quite upset, and I told him so. And he told me something like, well that’s what they do, and I said, ‘Well that doesn’t meet my needs’, and ‘I’m the customer’, and he said ‘No, she’s our customer’ and I really got quite angry.” (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013) | ||

| “Well, from my perspective, I would want to be not just a number or a name on a piece of paper. I’m a person. And, as such, you’re dealing with me as a one-to-one person. I’d want to be dealt with by the health professionals that way.” (Gilmour & Huntington, 2005)“It helped because he was the only person who seemed to tell me the truth, that was what I wanted.” (Harman & Clare, 2006)“…there is a great solidarity here in the village… there is never anyone who are foes… everyone is so kind… I find a great consolation in having these people around me…” (Karlsson et al., 2014)“I think I would rather they talked to me as though I was normal and just pick me up when I’m wrong if you like to put it that way, without being too unkind about it […] I might feel a bit silly but none the more for that, it… it would be better to be told I think” (Langdon et al., 2007)“My friends have mostly gone out of their way [to be supportive]. We’ve very good friends” (Macrae, 2008)“The most important thing I like is for my family to support me, love me, and not force me to do things I do not want to do.” (Mok et al., 2007)“The feeling of forgetfulness is a very difficult to take. My children never scold me; rather they comfort me and teach me how to do things, and my son is very patient and good-tempered. He understands that I am afraid and scared. It is the feeling of guilt that makes me feel uncomfortable. It is like forgetting to do my homework and, in the end, the teacher does not punish me. I do not want to disclose my feelings to my children because I am afraid they would not ask me to do anything anymore. Furthermore, I do not want them to worry about me. I am afraid they will find me useless.” (Mok et al., 2007)“If you know that at 10 or 11 I can go to the store and buy a newspaper, then that’s something to look forward to and then I meet a bunch of people, I’m friends with almost everyone at the store and I think that’s… and I hear many people say they’ve met me at the store and exchanged thoughts. They appreciated it and I do too” (Olsson et al., 2013) | ||

| “People tend to talk about them behind your back rather than to your face.” (Harman & Clare, 2006) | ||

| “They thought that I was drunk. It is awful to be treated that way when it in fact is other things you need help with.” (Holst & Hallberg, 2003) | ||

| “Nowadays you see everybody puts me down including Jim [live-in-carer], puts me down as a loser you see and I wish to discuss something but if they come it always gets foolish idiot, they will turn around and say ‘oh well, it’s no good discussing it with him because he wouldn’t know the first thing about it.” (Langdon et al., 2007) | ||

| “I haven’t told anyone. I think they will treat me differently. I wouldn’t be upset though, it depends what they know. If they have heard about it and don’t understand they would treat me differently. They think it’s something bad–they would scorn you and not want to come near you and fully believe that you are like that.” (Langdon et al., 2007) | ||

| “I don’t need anybody to do my work [My daughter] will do things for me but I can still (pause) And she gives me a row when I start to do windows She says, ‘Mother, stop doing that!’ I think she thinks (pause) because (pause) I’m old” (Robertson 2014) | ||

| “Not as many people come around anymore” (Macrae, 2008) | ||

| “I say to them [her daughters], ‘Let me help wash the curtains and put them up again’. They say ‘No, no. It is better you stand and watch. We’ll do the entire job ourselves’. I don’t know what to do during the day” (Mazaheri et al., 2013) | ||

| “I like playing mah-jong and going out, but no longer can I do it now because no one will take me out.” (Mok et al., 2007) | ||

| “She’s (wife) very supportive, yes, er, I won’t say dependent, but essential” (Preston et al., 2007)“…there’s people that are about in the same stages as I am, and I think that’s important…. And we talk back and forth about things we do and things we do wrong and stuff, and I think that helps a lot. It doesn’t make you feel so isolated.” (Werezak & Stewart, 2009) | “My life is lonely…very lonely. My daughter doesn’t come to see me; none of my children come to see me. Sometimes I would like to talk to one or other of them.” (Moyle et al., 2011) | |

| “It doesn’t bother me anymore, but it did at first… I had the concept that, well, “he’s not all there,” and [I was] very seldom asked for an opinion or anything of that nature.” (Werezak & Stewart, 2009) | ||

| Physical environment | “I just don’t go very far really, I keep to where I live you know….Where I know I’ll see people I know….I feel comfortable in [town]... I just don’t go very far really, I keep to where I live you know. I can come into [town] mind because me son lives in [town], well I just head for his house you know.....I think you know yourself how, where to go and who you know, where to visit and things like that” (Brittain et al., 2010) | “Oh Lord I hope I don’t have it [Alzheimer’s disease] . . . because when you have it, it is terrible. I knew somebody who had it and then they put her in a home and that made her worse.” (Lawrence et al., 2011) |

| “I’d feel like a prisoner if I wasn’t able to go out… it would be horrible, it would be terrible, I don’t want to be trapped inside, never.” (Olsson et al., 2013) | ||

| “I do stupid things at times. I did one the other day. I just wasn’t’ thinking. I was heading for one place and ended up in another. If I’m out someplace, there have been some times when I’ve been concerned about how to get back to the house” (Phinney, 1998) | ||

| “Our family, a lot of people say to us, ‘Oh, what are you doing in this great big house?’ I’ve probably said this to you before, but we love this house. We love this position, and we can cope with it, as long as [husband’s name] can still mow the lawn.” (Gilmour & Huntington, 2005) | ||

| “Well, I just won’t get up and go someplace. I give it thought, and I might write on a piece of paper where I came from or what streets to take to get back again. I’ve done that once or twice, but uh, because I, with all those avenues and everything I could get lost in a hurry. I wouldn’t know to go left or right or whatever.” (Phinney & Chesla, 2003) | ||

| “As long as I can be outside and do things I’ll have an identity” (Olsson et al., 2013) | ||

| “It (being outdoors) reminds me that there is still a lot of life left to be lived.” (Olsson et al., 2013) | ||

| Sociocultural environment | Marginalisation and instrumental preoccupations: “I remember what I want to remember. I don’t forget to pay my rent, to pay the hydro, etc. I eat, I sleep. Listen, dear, I’m 75 years old. Life’s not the same when you’re older.” (Hulko, 2009) | Privilege and socio-emotional preoccupations: “I’m concerned about [my wife] um having the same feeling, you know is this going to be steep or shallow or what is it going to be and how is it going to affect both of us and what, what’s, what um can we do or you know, you really feel that you’ve got no attack, from our point of view to prevent what’s going to happen.” (Hulko, 2009) |

| “Good doctors don’t knock you down with big words [like dementia] which could frighten a lot of people to death couldn’t it?” (Langdon et al., 2007) | ||

| “I think the whole class of problems that Alzheimer’s disease belongs to are the most frightening name you could find in the language, I think… dementia… Because when I was a youngster, the whole of society didn’t refer to that group of, ah, diseases by any particular name at all… and as they’re aware, it came from, you know, the adjective from that is demented and a demented person is a loony and a loony is somebody you put in… an asylum… | ||

| Now I’ve got this strongly in my mind… that I am being told in the gentlest of ways that I may be suffering from early dementia in one form or another and I… I still can’t… disconnect… that word from the asylum…” (Gilmour & Huntington, 2005) | ||

| “I don’t like the word [dementia] because it means mindlessness” (Langdon et al., 2007) | ||

| “Horrible sounding name anyhow, Alzheimer’s disease you know, it can make you sound as if you’re very gnarled— something about the word disease, I think it’s a very bad choice of name for it” (Langdon et al., 2007) | ||

Theme 1: Living With Change

Cognitive Capacity

Results of most studies indicate that PWD have insight into changes in their cognitive capacity which in many studies (e.g., Caddell & Clare, 2011; MacQuarrie, 2005) was indicated as the primary consequence of dementia. In particular, changing awareness and memory function were recognized as most impactful in terms of people’s experience.

In their proposed theory of a continuous process of adjusting to early-stage dementia Werezak and Stewart (2009) recognized changing levels of awareness as a link connecting each stage of the condition and affecting the process of adjustment between these stages. Phinney, Wallhagen and Sands (2002) highlighted how the degree of awareness impacted upon participants’ interpretation of the experienced symptoms and their response in dealing with them. Those who were aware of their symptoms were reported as more likely to acknowledge their difficulties and to accept support from others. PWD who were identified as having limited or mixed awareness often struggled to understand what was happening in their lives, resulting in frustration, embarrassment, shame, and difficulty accepting external support.

Changes in memory function were acknowledged by participants as impacting upon their experience of living with dementia. PWD differed in their interpretation of the origin of these changes. Some saw them as natural part of ageing (e.g., Langdon, Eagle, & Warner, 2007), others made a clear link between deteriorating memory and dementia (e.g., Harman & Clare, 2006). Problems with memory were identified as affecting various areas of people’s lives including their ability to successfully accomplish their daily activities and participate in life (e.g., Caddell & Clare, 2011; Lawrence, Samsi, Banerjee, Morgan, & Murray, 2011), to effectively communicate with others (Moyle, Kellett, Ballantyne, & Gracia, 2011) and to maintain social relationships (Langdon et al., 2007). They were associated with changes in a sense of self and other people’s perceptions of, and attitudes towards, PWD; as well as with loss and uncertainty (e.g., Holst & Hallberg, 2003; Mazaheri et al., 2013; Mok, Lai, Wong, & Wan, 2007).

Emotions

The experience of being diagnosed and living with dementia has been recognized as a source of various and, at times, conflicting emotions. It was identified that the process leading to diagnosis is often associated with fear and uncertainty regarding future life with the condition. This was related to the societal perceptions of dementia as an illness affecting memory and general function, which became synonymous with ill mental health and with eventual consignment to institutional care (Gilmour & Huntington, 2005). Coming to terms with a diagnosis was also described as a difficult process, associated with periods of depression and resistance. However, many participants reported that adjustment, although often disrupted by progressing deterioration in various areas of function, was possible. This adjustment could take different forms, from quiet resignation and developing an attitude of “getting on with things” to a conscious decision to embrace life and “make the most of things” (e.g., Macrae, 2008).

It was recognized that living with dementia encompasses experiencing both negative and positive emotions. Anger, embarrassment and frustration were commonly associated with the reduced ability to accomplish activities caused by deficits in cognitive, physical and communication and interaction skills (Caddell & Clare, 2011). Difficulties experienced with respect to the ability to interact with people, to engage in effective communication and share experiences with others, were highlighted as sources of insecurity, shame and feeling disabled (Holst & Hallberg, 2003). However, positive feelings such as optimism, satisfaction, love and appreciation, were also frequently expressed by PWD across the included samples (e.g., Karlsson, Sävenstedt, Axelsson, & Zingmark, 2014; Ostwald, Duggleby, & Hepburn, 2002).

Participation and Performance

It was highlighted that PWD often experience disengagement from activities, which was mainly associated with the loss of skills, decreased confidence and/or lack of support. The loss of abilities included process and motor skills as well as communication and interaction with others and was perceived as disruptive across various areas of participation (e.g., Moyle et al., 2011; Werezak & Stewart, 2009). In some cases, decreased activity engagement was reported to result not form complete loss of skills but the desire of PWD to preserve a sense of meaning associated with the activity, that is, engagement ceased as the ability to achieve the expected standard diminished (Holst & Hallberg, 2003). In other cases, reduction in activity was reported as a way of managing stress resulting from an inability to accomplish tasks successfully (Gilmour & Huntington, 2005).

Changes in the ability to do things were also related to decreased confidence and loss of motivation for involvement in various activities; gradual reduction in engagement in daily activities; and increased requirement for the support from others (Olsson, Lampic, Skovdahl, & Engrström, 2013; Gilmour & Huntington, 2005). These led to decreased participation in many areas of life and disengagement from everyday habits and practices (Holst & Hallberg, 2003; Vikström, Josephsson, Stigsdotter-Neely, & Nygård, 2008), which had a knock on effect on peoples’ pattern of social engagement and interpersonal relationships.

Sense of Agency

A number of studies considered issues related to the perceived loss of control experienced by PWD. Changes in the level of control were seen as affecting autonomy and independence of PWD and others were seen as making decisions directly affecting the lives of PWD and taking over their roles and responsibilities (Fetherstonhaugh, Tarzia, & Nay, 2013; Gilmour & Huntington, 2005). The ability to maintain control over decisions affecting them was associated by PWD with their perceived quality of life. Those who felt disempowered by others in terms of their involvement in determining what happens in their lives were likely to perceive their quality of life as poor. Those who felt in control, involved, and subtly supported in making decisions affecting them, reported being more satisfied with their situation.

Social Connectedness

Although companionship and the ability to engage in and maintain interactions with others, in particular positive, caring, and respectful relationships with family and friends, were identified in a number of studies as essential to wellbeing of PWD, it was also indicated that PWD experience a number of challenges in their relationships with people (e.g., Caddell & Clare 2011; Mazaheri et al., 2013; Mok et al., 2007). These appeared to relate to the loss of ability to connect with others and in particular to reduced communication and interaction skills. PWD frequently reported difficulty engaging in and sustaining meaningful, coherent conversations with others (e.g., Holst & Hallberg, 2003; Lawrence et al., 2011), which made them feel inadequate, ashamed, and often led to avoidance or withdrawal from social interactions.

Additionally, emotions experienced when people realize their loss of abilities, that is, feeling insecure and disabled; feeling like a burden to others or dependent on others; also appeared to be at play, resulting in negative emotional reactions, affecting people’s confidence, increasing their feeling of isolation and the tendency to avoid contacts with others (Werezak & Stewart, 2009).

Theme 2: Striving For Continuity

Coping Strategies

Resourcefulness of PWD in terms of coping strategies applied to maintain continuity in their lives was documented in a number of studies (e.g., Gillies, 2000; Parsons-Suhl, Johnson, McCann, & Solberg, 2008; Pearce, Clare, & Pistrang, 2002; Preston, Marshall, & Bucks, 2007). The strategies used were categorized in different ways by different authors, but the most frequently reported were strategies related to emotional, cognitive, and behavioral coping.

Emotional strategies used by PWD were often related to their personality. Those with generally optimistic outlook appeared to be more likely to adopt an accepting, “making the most of life” attitude, than those with more pessimistic traits. The most commonly reported emotional strategies included acceptance, determination, hope, humor, resignation, and denial. A number of authors identified a “coming to terms” process, which involved balancing hope and despair, resulting in a level of acceptance, allowing (or not) PWD to engage with the reality of a progressive disorder and to carry on with their daily lives (e.g., Clare, 2002; Macrae, 2008). A positive attitude and determination were identified as supporting peoples’ attempts to achieve a level of acceptance allowing them to lead meaningful, satisfying lives.

Compensation was identified as one of the cognitive strategies employed by PWD in addressing the experienced difficulties. This mostly involved relying on other people or physical objects within the immediate environment to provide support in facilitating successful performance. A number of studies reported use of cognitive exercises (e.g., memorizing poems) in order to keep an active mind and to preserve, to the extent possible and for as long as possible, cognitive abilities (Mazaheri et al., 2013; Phinney, 1998). Reappraising one’s abilities, relationships and roles and downgrading expectations towards self was reported as one of the strategies used by PWD to adjust to the experienced changes. This involved setting lower limits both for remembering things and for completing tasks (Pearce et al., 2002). Ignoring, minimizing or normalizing one’s experience were also identified by some authors as strategies employed by PWD to maintain a sense of continuity (MacQuarrie, 2005; Macrae, 2008).

A number of behavioral strategies, such as seeking reassurance and guidance from others in order to maintain the usual level of performance; maintaining or adapting routine to facilitate function; avoiding or withdrawing from those areas of life which prove challenging; or adjusting social relationships, were also identified as regularly used by PWD (Mok et al., 2007; Ostwald et al., 2002).

Participation

Despite changes experienced in this area, the ability to engage in activities, uphold roles, routines and independence, and to remain involved in the wider community were identified as important aspects in maintaining continuity and normality in life (Menne, Kinney, & Morhardt, 2002); validating the person as an agent in the world (MacQuarrie, 2005; Mazaheri et al., 2013); providing meaning and purpose in life (Werezak & Stewart, 2009); and maintaining distinctive features of one’s identity (Öhman & Nygård, 2005). Moreover, personhood and identity were reported to be demonstrated and, in part, confirmed through PWD’s involvement in everyday activities (Steeman, Tournoy, Grypdonck, Godderis, & de Casterlé, 2013).

Significantly, when considering the quality of life of PWD, the ability to do things and to contribute to their households and communities were reported to be more important than experienced dementia symptoms (Hulko, 2009). Engagement in activity was indeed recognized as a way of overcoming loneliness, maintaining interests and daily routines (Moyle et al., 2011), providing opportunities for social connection and facilitating a sense of autonomy (Öhman & Nygård, 2005). Hence, ability to do things and to participate was recognized as one of the main areas of need for PWD and a means of promoting continuity and quality of life.

Sense of Agency

It was highlighted in Theme 1 that PWD often report changes in their sense of efficacy and agency, which was associated with the loss of skills required for effective engagement in various activities and with the attitudes and actions of other people. The current review indicates, however, that the ability to maintain control over their affairs is important to PWD not only from the point of view of sustaining a degree of independence—it also appears to be an important aspect of maintaining a sense of self (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013; Karlsson et al., 2014).

The reviewed evidence indicates that PWD are aware of their changing ability to be fully involved in the decision making process and meeting their commitments and responsibilities to the same degree as before the onset of dementia. They also appear to acknowledge the progressive character of dementia and the fact that, with time, they may need increased support from others both in terms of making choices and doing things. However, what they wish for is respectful support, sensitive and proportionate to their level of ability and need, allowing maintenance of independence, dignity, and sense of self (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013).

Identity

It was indicated that PWD maintain their sense of identity through their journey with the condition, which is demonstrated through their personality traits, beliefs and opinions, actions, and activities (Caddell & Clare, 2011; Menne et al., 2002). However, it is essential to acknowledge that, according to a number of studies, PWD face losses and challenges which may pose a threat to their sense of self (Mazaheri et al., 2013; Steeman, Godderis, Grypdonck, de Bal, & de Casterlé, 2007). These challenges may require a shift in the core values of PWD and/or subtle support from their environment, if they are to be successfully overcome and meaningfully integrated into people’s lives (Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013; Steeman et al., 2013).

The loss of skills resulting in the decreased capability of PWD to successfully engage in daily activities and to fulfil their roles and responsibilities was highlighted as a potential cause for discontinuity between past and present self (Preston et al., 2007). This was associated with a feeling of worthlessness which was related to self-imposed norms or perceived or actual social expectations about competence and quality of performance in various areas of life. Consequently, PWD were reported to constantly balance their feelings of being someone retaining their value and someone losing their value. To do so, they appeared to weight their present sense of self-value against their past sense of self-value, their sense of self-value as anticipated in the future, and the sense of self-value as projected by others (Steeman et al., 2007). The outcome of this process was thought to determine the way PWD resolved the discontinuity in self caused by their experience of dementia-related changes.

Theme 3: Double Edged Impact of the Environment

It was recognized that sociocultural and physical environment can offer opportunities and enhance people’s experience of living with dementia as well as hinder their ability to adapt to continuously changing circumstances and pose threat to their identity. This twofold role of the environment was specifically referred to by Öhman and Nygård (2005) as double-edged environmental impact, but was evident throughout the reviewed articles (e.g., Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013; Werezak & Stewart, 2009). Key aspects of such impact are considered below.

Interpersonal Relationships

Interpersonal relationships were identified by PWD as crucial to their quality of life. Family members were valued for their role in compensating for lost skills and providing care but also for offering motivation, closeness, intimacy, sense of belonging, sense of purpose, and companionship (e.g., Hulko, 2009; Karlsson et al., 2014). PWD also frequently recognized and were appreciative of other important relationships, such as those with neighbors, friends, and local communities for their support and for offering a sense of continuity and camaraderie.

Although the ability to engage in and maintain interpersonal relationships was predominantly seen as having positive influence, it was recognized that, in some cases, interpersonal relationships may lead to disempowerment and even pose a threat to the way PWD experience and (re)formulate self (e.g., Fetherstonhaugh et al., 2013; Mazaheri et al., 2013; Robertson, 2014). For example, PWD highlighted the importance of an understanding, supportive attitude by important others reflected in subtle, respectful support, provided when required. Access to such support not only allowed PWD to maintain a level of participation but also to preserve their sense of agency and efficacy, their roles and status within family and social circles and, importantly, their sense of self. On the contrary, excessive, overprotective support, was perceived as disempowering, de-skilling, detrimental to PWD sense of agency and autonomy, and potentially leading to exclusion and/or isolation. Likewise, insufficient support was reported to be experienced as limiting and having a negative impact upon PWD experience. Finally, disrespectful attitudes reflected in patronizing behavior, denying PWD their autonomy and personhood, were found by them as particularly hurtful, unjust and inflammatory.

Physical Environment

The importance of physical environment, in terms of its impact upon PWD engagement in activity and participation, was highlighted in a number of studies (e.g., Brittain et al., 2010; Phinney & Chesla, 2003). In particular, it was reported, that PWD value being able to access and use outdoor spaces and that this ability is associated with a sense of wellbeing. Brittain and colleagues (2010) identified outdoor environments as a source of opportunities in terms of engagement in activity and enjoyment related to participating in the local community. However, some issues, in particular related to loss of confidence experienced by PWD, were also highlighted as hindering their potential to benefit from the continued engagement with the external environment. This loss of confidence was interpreted as related to fear of getting lost due to decreased orientation and anxiety experienced by other people which appeared to be recognized and mirrored by PWD. Consequently, a decreased ability to enjoy outdoor spaces and lack of required support to facilitate the safe use of outdoors was associated with loss of freedom and decreased quality of life (Olsson et al., 2013).

Familiarity of physical spaces and objects, offering context in which a person could maintain a sense of coherence and supporting maintenance of daily routines, was recognized as an important factor in terms of encouraging activity engagement (Öhman & Nygard, 2005). On the contrary, changes in the environment were associated with an increased risk of disruption to a routine, leading to a reduced sense of consistency and security and potentially resulting in a distress, loss of confidence, and inactivity (Lawrence et al., 2011).

Sociocultural Environment

Two articles considered the role of sociocultural factors relative to people’s experience of dementia (Hulko 2009; Lawrence et al., 2011).

Hulko (2009) focused on the implications of social location in terms of peoples’ gender, ethnicity, and class. The results of her study suggest that social background may play a role in the way people experience dementia. Namely, Hulko (2009) indicated that people from more marginalized backgrounds did not see dementia as problematic as long as their memory problems did not interfere with their ability to engage in their daily activities and meet their daily needs. Hulko (2009) referred to these needs as “instrumental preoccupations.” On the other hand, people with a more privileged background were identified to be preoccupied with, what Hulko (2009) described as, socio-emotional concerns such as impact of dementia on their family members, particularly burdening their loved ones. As a result they experienced the condition as more distressful than more disadvantaged participants.

Lawrence and colleagues (2011) considered the subjective reality of living with dementia from the perspective of PWD within the three largest ethnic groups in the United Kingdom: White British, Black Caribbean, and South Asian. The authors reflected upon the relationship between PWD’s ethnic background and their understanding of the condition, attitudes surrounding support needs and dementia’s interference with individuals’ roles, relationships, and activities; and how these shaped participants’ overall experience. It appears that the experience of these aspects of life varied depending on peoples’ ethnic background, suggesting that sociocultural factors are indeed at play in shaping people’s experience in dementia.

Discussion

This metasynthesis examined the qualitative literature focused on the firsthand experience of living with dementia, with the specific focus on relationships between factors affecting peoples’ experience and issues pertaining to participation and adaptation. The first theme considered condition-related changes experienced by PWD and showed how these interlink and impact upon various areas of people’s lives. The second theme indicated that amidst these changes, PWD strive to maintain continuity in their lives by employing various coping strategies. The third theme underlined the importance of contextual factors relative to people’s experience of living with dementia.

The presented results suggest that people’s experience of living with the condition is shaped by multiple personal and environmental factors which remain in a constant, transactional relationship to each other and determine the way people adjust to the experienced changes over time (Figure 2). This is in line with the dynamic systems theory (Thelen, 2005) which considers experience from many levels, from molecular to cultural; and views development as emergent, nonlinear, and multidetermined. However, although extensive literature in relation to firsthand experience of dementia is available, to-date its dynamic, transactional character has not been fully recognized. A number of the included studies highlighted both personal and environmental factors as shaping experience of PWD and indicated that people’s experience is characterized by “tension” or a “state of flux” relative to experienced changes and the need for continuity in their lives (e.g., Caddell & Clare, 2011; Phinney, Dahlke, & Purves, 2013; Preston et al., 2007; Steeman et al., 2013). However, none of these studies considered the dynamic relationship between personal and environmental factors that are at play and affect people’s experience or mechanisms/processes that affect their ability to resolve such “tension.” Rather, the discourse presented in the reviewed studies largely reflects the view of a person with dementia as a closed system, isolated from his or her environment and gradually disintegrating as a result of internal deterioration; dominant in Western societies (Guendouzi & Müller, 2006). The reasons for this may relate to the fact that, the majority of the included studies were completed within a descriptive/interpretive qualitative methodology, predominantly based in phenomenology; with few underpinned by a specific theoretical framework to guide study design and interpretation of findings.

Thus, the results of this metasynthesis are significant in recognizing the dynamic relationship between factors shaping experience in dementia, but we acknowledge that further research is required not only to identify the key factors impacting upon people’s experience but also to consider processes and mechanisms that determine the potential for adjustment to the experienced changes. This metasynthesis indicates that personal resources such as cognitive capacity, personality and affect, sense of agency and self-efficacy, skills for social connectivity and coping strategies; and characteristics of one’s environment both social and physical and wider cultural context; have implications in terms of experience of dementia. However, further research is needed to clarify which of these factors are key in shaping people’s experience and how they interact to affect it. For example, our findings indicate that environment plays a key role in people’s experience of dementia. At first glance this is not a new insight as the role of environment, both social and physical, in relation to people’s well-being has been recognized on a theoretical level, markedly within the World Health Organization (2001)International Classification of Function, Disability and Health. Also, in the context of dementia, the role of social environment was previously highlighted by Kitwood (1998) in his theory of personhood and person-centered care. However, although there is some research evidence suggesting that both physical (Fleming, Kelly, & Stillfried, 2015) and sociocultural aspects (Hulko, 2009; Lawrence et al., 2011) are at play, the complex interactions between these factors and the person have not been explored in terms of the processes and mechanisms involved. Additionally, as the presented findings indicate the emerging character of the experience in dementia, further study is also required to enhance current understanding of this temporal aspect of people’s experience. Expanding our knowledge and insight into these issues has the potential to impact upon support efforts as, better understanding of multiple factors that shape people’s experience in dementia as well as processes and mechanisms determining how multiple personal and environmental factors shape people’s experience over time, may affect how PWD are perceived and related to in wider society and, where required, open new avenues for both formal and informal carers to more effective and ethical ways of support. The dynamic system theory provides theoretical principles for conceptualizing, operationalizing, and formalizing complex interrelations of time, influencing parameters (within person and both physical and sociocultural environment), and process and for understanding the process of change (Thelen, 2005). It can, perhaps, provide a useful guiding structure for future research.

The reviewed literature shows that PWD employ a myriad of adaptive strategies to maintain continuity in their lives. Although not all of these strategies may lead to positive adaptation and their effectiveness may change with the progression of dementia; these results confirm findings reported by de Boer and colleagues (2007) that PWD are aware of their condition and continuously engage in efforts to respond to threats posed by dementia related changes. The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness (Paterson, 2001) implies that person’s experience of a health condition, that is, whether they focus on wellness or illness, depends on their perception of a threat to control. Paterson (2001) explains that threats to control are personally defined (e.g., signs of disease progression, loss of skills, disease-related stigma) and their impact may change over time but, once the level of threat exceeds the person’s level of tolerance, it causes a shift from wellness to illness in the foreground, affecting the individual’s ability to cope. The relationship between sense of control and potential for adaptation has been identified in the literature. Kielhofner (2008) argues that sense of control is required for self-efficacy which has been identified as a vital resource for dealing with age related changes relative to health, cognitive function or ability to successfully participate in life (Artistico et al., 2011). Studies included in this metasynthesis document changes to sense of control and agency experienced by PWD due to internal and external threats, but stop short of exploring how this relationship can be utilized to enhance their potential for adaptation. Perhaps the relationship between sense of control and agency, self-efficacy, and potential for adaptation in dementia requires further attention by both researchers and clinicians, to foster a better understanding of people’s experience of living with the condition and how it could be used to the advantage of PWD and in order to enhance care efforts. Again, it could be argued that, as offering a means for exploring and explaining the nature and process of change in adults (both adaptive and maladaptive) (Keenan, 2010, 2011) the dynamic systems theory can provide a useful framework to guide future research into the process of change and adaptation in dementia.

Being able to participate in life was identified in this metasynthesis as important for PWD. On one hand, it was reported that they experienced changes in the ability to take part in their usual activities and to remain socially engaged; on the other, they identified the ability to do so as pivotal for maintaining continuity and wellbeing in life. The association between participation, engagement in activities and health has been convincingly argued for within the literature on human occupation (Kielhofner, 2008; Polatajko & Townsend, 2007) and is recognized within the current conceptualization of health (World Health Organization, 2001). Kitwood (1998) identified participation in occupations as one of the main psychological needs of PWD and its role in the wellbeing of PWD is supported by research (Hasselkus & Murray, 2007). Moreover, recent literature review (Fallahpour, Borell, Luborsky, & Nygård, 2016) concluded that participation in cognitive, physical and social activities might significantly contribute to prevention of cognitive decline in later-life. However, it has been asserted that important aspects of occupational engagement, for example, subjective experience and personal aspects of participation in activity, which may influence its role in preventing or adapting to life with dementia, have not been explored (Fallahpour et al., 2016). Furthermore, the existing evidence lacks theoretical underpinnings and methodological consistency, which limits its clinical utility (Fallahpour et al., 2016). Consequently, further research, focused on the subjective experience of engagement in activity by PWD, is required to develop a better understanding of how activity could be effectively utilized to enhance their outcomes relative to health, wellbeing and adaptation to dementia related changes.

The main limitation of this review relates to the complexity of dementia experience. PWD are not a homogeneous group (Guendouzi & Müller, 2006). They are individuals whose experience is shaped over time by various personal and contextual factors which are in constant dynamic, nonlinear relationships to each other, resulting in unique, personal stories. Capturing the essence of this experience while aiming to reflect its complexity, based on highly heterogeneous research evidence, is challenging. Nevertheless, this meta-synthesis is seen as a call for further research that will explore and expand the application of dynamic systems theory and concepts relative to participation in occupations in terms of their relevance to issues of adjustment and adaptation in dementia.

Conclusions

This metasynthesis examined the qualitative literature focused on the firsthand experience of living with dementia, with the specific focus on relationships between factors affecting peoples’ experience and issues pertaining to participation and adaptation. The reviewed evidence shows that, amidst the continuous changes, PWD strive to maintain continuity in their lives and there are many coping strategies and protective factors at play to facilitate this. It appears that the emerging experience is influenced by access to and quality of both personal and contextual resources. These findings were interpreted and discussed in the context of relevant theoretical frameworks and research evidence. It was considered that current evidence and findings presented in this review can be further explored and expanded upon in a more systematic way through research conducted within the theoretical framework of the dynamic systems theory (Thelen, 2005). It was also concluded that further research would be beneficial to explore the subjective experience of dementia from a participatory perspective. Exploring the application of these theoretical perspectives would contribute to the current state of knowledge and offer both PWD and carers fresh perspective on the nature of change and potential for adaptability in dementia.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at The Gerontologist online.

Funding

Work completed as part of PhD process supported by Queen Margaret University Edinburgh.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to express her gratitude to colleagues within Firefly Research, Queen Margaret University Edinburgh, in particular Dr. Ian Finlayson, Michele Harrison and Susan Prior, who offered support and feedback whenever requested. She would also like to acknowledge the researchers and participants who contributed to the primary publications included in this review and thank them for providing such a rich body of literature to work with. Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- Alzheimer Disease International (2009). World Alzheimer Report. London: ADI. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Disease International (2012). World Alzheimer Report 2012. Overcoming the stigma of dementia. London: ADI. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Disease International (2015). World Alzheimer Report 2015. The Global Impact of Dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: ADI. [Google Scholar]

- Artistico D. Berry J.M. Black J. Cervone D. Lee C., & Orom H (2011). Psychological functioning in adulthood: A self-efficacy analysis. In Hoare C. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Reciprocal Adult Development and Learning (pp. 215–247). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso J., Powell-Cope G. M. (2000). Metasynthesis of qualitative research on living with HIV infection. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 340–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R., & O’Connor D (2010). Broadening the dementia debate: Towards social citizenship. Bristol, UK: Policy Press Scholarship Online. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K., Corner L., Robinson L., Bond J. (2010). Ageing in place and technologies of place: the lived experience of people with dementia in changing social, physical and technological environments. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32, 272–287. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn F. Goodman C. Sworn K. Rait G. Brayne C. Robinson L.,…Iliffe S (2012). Psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of dementia diagnosis and treatment: a systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Medicine, 9, e1001331. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddell L. S., Clare L. (2010). The impact of dementia on self and identity: a systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 113–126. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddell L. S., & Clare L (2011). I’m still the same person: The impact of early-stage dementia on identity. Dementia, 10, 379–398. doi: 10.1177/1471301211408255. [Google Scholar]

- Clare L. (2002). We’ll fight it as long as we can: coping with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging & Mental Health, 6, 139–148. doi:10.1080/13607860220126826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly J., Willis K., Small R., Green J., Welch N., Kealy M., Hughes E. (2007). A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 43–49. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer M. E., Hertogh C. M., Dröes R. M., Riphagen I. I., Jonker C., Eefsting J. A. (2007). Suffering from dementia - the patient’s perspective: a review of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics, 19, 1021–1039. doi:10.1017/S1041610207005765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallahpour M., Borell L., Luborsky M., Nygård L. (2016). Leisure-activity participation to prevent later-life cognitive decline: a systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 23, 162–197. doi:10.3109/11038128.2015.1102320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetherstonhaugh D., Tarzia L., Nay R. (2013). Being central to decision making means I am still here!: The essence of decision making for people with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 143–150. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld D. L. (2003). Metasynthesis: The State of Art – So Far. Qualitative Health Research, 13, 893–904. doi:10.1177/1049732303253462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R. Kelly F., & Stillfried G (2015). ‘I want to feel at home’: establishing what aspects of environmental design are important to people with dementia nearing the end of life. BMC Palliative Care, 14. doi: 10.1186/s12904-015-0026-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies B. A. (2000). A memory like clockwork: Accounts of living through dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 4, 366–374. doi:10.1080/713649961. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour J. A., Huntington A. D. (2005). Finding the balance: living with memory loss. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 11, 118–124. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendouzi J.A., Müller N. (2006). Approaches to discourse in dementia. Mahwah, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Harman G., Clare L. (2006). Illness representations and lived experience in early-stage dementia. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 484–502. doi:10.1177/1049732306286851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselkus B.R., & Murray B.J (2007). Everyday occupation, well-being, and identity: the experiences of caregivers in families with dementia. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 9–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst G., Hallberg I. R. (2003). Exploring the meaning of everyday life, for those suffering from dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 18, 359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulko W. (2009). From ‘not a big deal’ to ‘hellish’: experiences of older people with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 23, 131–144. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2007.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- Innes A., & Manthorpe J (2012). Developing theoretical understandings of dementia and their application to dementia care policy in the UK. Dementia: the International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 12, 682–696. doi:10.1177/1471301212442583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson E., Sävenstedt S., Axelsson K., Zingmark K. (2014). Stories about life narrated by people with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 2791–2799. doi:10.1111/jan.12429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan E. K. (2010). Seeing the forest and the trees: Using dynamic systems theory to understand “Stress and coping” and “Trauma and resilience”. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 20, 1038–1060. doi:10.1080/10911359.2010.494947. [Google Scholar]