Abstract

Background

Twenty-five percentage of patients who are transferred from hospital settings to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are rehospitalized within 30 days. One significant factor in poorly executed transitions is the discharge process used by hospital providers.

Objective

The objective of this study was to examine how health care providers in hospitals transition care from hospital to SNF, what actions they took based on their understanding of transitioning care, and what conditions influence provider behavior.

Design

Qualitative study using grounded dimensional analysis.

Participants

Purposive sample of 64 hospital providers (15 physicians, 31 registered nurses, 8 health unit coordinators, 6 case managers, 4 hospital administrators) from 3 hospitals in Wisconsin.

Approach

Open, axial, and selective coding and constant comparative analysis was used to identify variability and complexity across transitional care practices and model construction to explain transitions from hospital to SNF.

Key Results

Participants described their health care systems as being Integrated or Fragmented. The goal of transition in Integrated Systems was to create a patient-centered approach by soliciting feedback from other disciplines, being accountable for care provided, and bridging care after discharge. In contrast, the goal in Fragmented Systems was to move patients out quickly, resulting in providers working within silos with little thought as to whether or not the next setting could provide for patient care needs. In Fragmented Systems, providers achieved their goal by rushing to complete the discharge plan, ending care at discharge, and limiting access to information postdischarge.

Conclusions

Whether a hospital system is Integrated or Fragmented impacts the transitional care process. Future research should address system level contextual factors when designing interventions to improve transitional care.

Keywords: Care transitions, Systems of care, Care integration, Qualitative

Hospital to skilled nursing facility (SNF) transitions are frequently suboptimal. Communication between the hospital and SNF is often unidirectional and poor in quality (Kind, Thorpe, Sattin, Walz, & Smith, 2012; King et al., 2013; Polnaszek et al., 2015; Walz, Smith, Sattin, & Kind, 2011). Families and patients are often not prepared for the SNF setting (Coleman, 2003). SNF staff are generally dissatisfied with transitional hand-offs from the hospital, which they report are often poor and increase risk for misaligned care and early rehospitalization (Coleman, 2003; King et al., 2013). This is a critical problem, as reflected by the 25% of Medicare patients discharged to a SNF who are rehospitalized within 30 days (Mor, Intrator, Feng, & Grabowski, 2010).

Multiple experts and professional societies have called for improvement in care quality and accountability during hospital to SNF transitions (Snow et al., 2009), yet few evidence-based interventions are available to improve these processes at the system level. Achieving high-quality, bidirectional communication between these settings at a system-wide level has proven to be extremely difficult (Coleman, 2003) yet identified as critical to attaining a safe transition for patients (Ouslander et al., 2016).

To inform the design of targeted system-level interventions to improve hospital to SNF transitions, a better understanding of approaches to such transitions is needed. We conducted a large, multihospital, multidisciplinary study within a rural Midwestern area to sample a variety of health system structures in communities having similar cultures. Our specific goal was to examine how participants approached transitioning care from hospital to SNF, what actions they took based on their understanding, and conditions influencing their actions in various health system types.

Methods

Research Design

A qualitative study was conducted using grounded dimensional analysis (GDA), a variant of grounded theory (Bowers & Schatzman, 2009; Kools, McCarthy, Durham, & Robrecht, 1996; Schatzman, 1991), to explore how acute care providers (medicine, nursing, case management) transition patients from hospital to SNFs. GDA is particularly well suited to discovery in areas about which little is known (how acute care providers transition care from hospital to SNF) (Bowers & Schatzman, 2009). GDA is an inductive approach that uses systematically applied methods to identify linkages between how individuals understand complex processes (e.g., care coordination/hospital discharge) and the actions that they take as a result of their understanding (Caron & Bowers, 2000; Kools et al., 1996). The end product of GDA is a conceptual model capable of explaining these actions as well as the conditions (social and individual factors) that contribute to variations in participants’ behavior (Caron & Bowers, 2000). These conceptual models illustrate the complexity and variation within the primary process of interest (hospital discharge) and thus are supportive in identifying opportunities for future intervention. The development of the conceptual model relies directly upon participants’ experiences which are collected through in-depth interviews to gather rich data.

Setting and Participants

Between February 2014 and November 2014, data were collected from 64 acute care providers (15 medical doctors [MDs]—1 primary care physician and 14 hospitalists, 31 staff registered nurses, 8 health unit coordinators, 6 case managers, 4 hospital administrators—2 directors of nursing and 2 directors of discharge planning) from 3 hospitals in rural Wisconsin. Facility characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participating Hospital Characteristics

| Facility | Hospital type | Location | Bed count, n | City population, n | Participants per hospital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Trauma Center Level II, academic | Rural | 504 | 18,952 | 34 |

| 2 | Trauma Center Level III, nonacademic | Rural | 69 | 14,930 | 13 |

| 3 | Critical Access, nonacademic | Rural | 25 | 2,395 | 17 |

Participants were recruited through announcements at staff meetings. Participation was voluntary. All interviews were conducted in a private room and occurred during paid work time for participants. Specific characteristics of participants were not collected as sampling decisions in GDA are based upon emergent data rather than subject characteristics (Strauss, 2003). This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin- Madison Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection and Analysis

In-depth interviews were conducted in nine focus groups and one individual interview and lasted 45–60 min. Size of the focus groups varied from 2 to 10 participants. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. All transcribed interviews were checked against the audio recording to ensure accuracy. During GDA, data collection and analysis occur in a cyclic process (Corbin & Strauss, 2008), meaning that immediately after each focus group, data were analyzed which informed the development of new interview questions. Initially, interview questions were open to allow for participants to define and describe their experiences with transitioning care. For example, one open question that was posed to all participants was, “describe how you transition care to nursing home settings?” Over the course of the study, subsequent interview questions became more focused to understand the interrelation among important concepts and to assist with developing the conceptual model. An example of focus questions asked were, “some participants have talked about how they communicate with staff in the nursing home. Can you describe how you go about communicating with nursing home staff?” or “when you think of nursing homes, what do you imagine or what has been your experience visiting or working with nursing homes?”

Data analysis occurred within an eight-member qualitative research team consisting of PhD prepared nurses, physicians, pharmacist, and two research assistants. Data were analyzed using open, axial, and selective coding (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Open coding involved a line-by-line analysis to examine how acute care providers understood transitioning care between hospital to SNF, what actions they took based on their understanding, and what conditions influenced their actions. Axial coding involved specifying the context of key concepts (e.g., how and under which situations certain actions took place) and identifying dimensions within categories that had been discovered during open coding. Selective coding was used to integrate all categories and to develop the conceptual model (Strauss, 2003) which illustrates the process of transitioning care from hospital to SNF. Analysis also occurred during interview sessions to facilitate ongoing constant comparison of situations in order to identify variability and complexity, a foundation of GDA (Caron & Bowers, 2000; Strauss, 1987).

Several factors were used to determine adequate sample size, including the extent of saturation (no new information provided or emergence of new categories) and the scope, quality, and complexity of data elements (Morse et al., 2009). Methodological strategies used to ensure rigor included use of a multidisciplinary team to analyze data, member checking to determine if categories were relevant, and use of memos to inform sampling, data collection, and analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Results

Overview

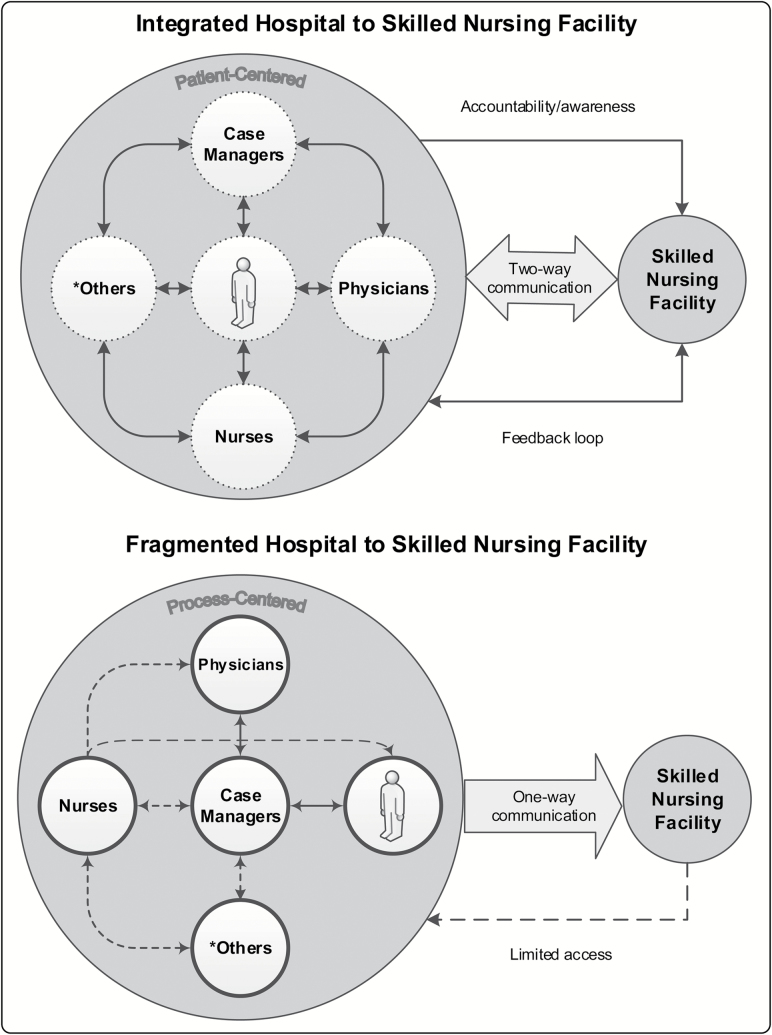

Acute care staff across hospital systems described three common categories when facilitating transitions from hospitals to SNF: Developing the Discharge Plan, Communicating the Discharge Plan, and Achieving the Discharge Plan. While these overall categories were consistent across hospital settings, staff reported that specific actions undertaken to achieve transition and coordinate care between settings varied substantially. Staff attributed this variation to the degree of integration or fragmentation within the hospital system. Staff in Integrated Systems generally described hospital to SNF transitions as centering on patient needs and consistently used the term “transitioning.” Conversely, staff from Fragmented Systems focused on the overall goal of discharging patients quickly to free up a bed and used the term “discharging” when describing their transitional care process (see Figure 1, conceptual model).

Figure 1.

Process of transitioning based on hospital context. *Others may include, unit clerks, pharmacist, social workers, physical therapist, and other health care providers. Dashed arrows represent connections between providers and patients that are inconsistent. Solid arrows represent connections between providers and patients that are consistent.

Developing the Discharge Plan

Integrated System

Integrated Systems relied on collaborating with others and had an awareness of the SNF environment which allowed staff to develop a discharge plan that supported a safe and smooth transition, did not make patients or families feel rushed, and ensured continuity of care across settings. Collaborating with others was described in Integrated Systems as a complex, recurrent process that resulted in a comprehensive, patient-centered discharge plan developed with input from direct (physician, nurses, and rehabilitation therapists) and indirect (case managers or discharge planners) care staff, as well as patients and their families. Changes in patient condition, care needs, or patient/family preferences for SNF site were communicated across the provider team during daily interdisciplinary rounds during which each member of the healthcare team provides information on patient progress, concerns regarding the next point of care, and patient and family responses to the plan.

“We round on patients every morning, we want to know what’s going on from the patient’s perspective. We stay in close contact with the floor nurses. If there is a patient concern we talk about it.” (Focus Group 13, MD 1)

Awareness of the SNF environment by hospital staff included knowledge of the range of care services provided, staffing configuration, and identity. Staff reported that these factors were important and helped reduce inappropriate transfers, for example, sending a patient with acute needs that cannot be managed by the SNF; ensured complete, accurate, and patient-centered discharge orders; improved communication; and assisted providers in preparing patients and families for what to expect in the SNF. Participants described intentional efforts to increase awareness of the SNF environment by arranging face-to-face contacts with SNF staff and monthly work sessions to improve the transition process.

“We work together to improve our process. If we mess up they [skilled nursing facility] tell us and we tell them when things don’t go as smoothly. We have monthly meetings to work things out.” (Focus Group 4, RN 5)

Fragmented System

Fragmented systems rushed to complete the plan and had limited awareness of the SNF environment. Staff in these systems reported that this was suboptimal, leaving families feeling rushed and anxious about the transition and creating opportunities for medical errors. Rushing to complete the plan was described as starting the discharge plan 24 hr or less before discharge, leaving little time for collaborating with others or integration of patient and family preferences for care, and little time for creating optimal discharge documentation. Rushing to create discharge documentation forced physicians to make educated guesses about correct discharge orders for patients new to them and increased their discharge workload. Few staff reported awareness or concern about quality of the discharge plan. Further, staff reported that there was little opportunity to directly involve patients and families.

“Sometimes we will pick the wrong solution (for wound care). I can’t find what it is so I just say wound care per order” (Focus Group 10, MD 5).

In Fragmented Systems, case managers communicated details of the plan to patients and families and were seen as central and necessary to quickly moving patients out of the hospital. Further, staff in Fragmented Systems did not employ strategies to decrease patient and family anxiety about the transfer.

“The case managers are the best, they do all the work” (Focus Group 10, MD 7).

Staff in Fragmented Systems reported limited awareness of the SNF environment. Some viewed SNFs as an extension of the hospital and assumed that any acute care need could be managed in that setting. Others believed services such as rounding physicians and onsite pharmacy were available 24 hr per day. Physicians in Fragmented Systems reported that they were often unable to answer patient and family questions about specific SNFs and often referred families to case managers.

“They ask me about the nursing home, I don’t know anything about nursing homes. I tell them to talk to the case manager.” (Focus Group 10, MD 8)

Communicating the Discharge Plan

Integrated System

Integrated Systems generally utilized both unidirectional and bidirectional communication at multiple time-points before patient discharge to convey the discharge plan. Staff in these hospital systems noted that this strategy provided an opportunity for review, clarification, preparation, and feedback with the receiving SNF team. On the day of discharge, in addition to faxing medical and nursing discharge summaries several hours before transfer, staff followed up with verbal reports of patient status directly to SNF staff, allowing direct, real-time, two-way communication.

Nurses used verbal handoffs to report patient clinical and functional status, clinical parameters that would require continued monitoring, behavioral concerns, for example, wandering or confusion, and tips for providing care, for example, patient preference for medication administration. Case managers used verbal handoffs to communicate equipment and rehabilitation consult needs. Acute care physicians employed verbal handoffs to SNF clinicians to convey information about the admission and pending diagnostics or follow-up appointments.

“We speak directly with the doctors and nurses. Many of us pick up the phone and call the providers directly.” (Focus Group 12, MD 1)

Fragmented System

In Fragmented Systems, communication between hospital and SNF staff was indirect, unidirectional, and occurred primarily by text (fax copy of chart). Physicians and staff nurses in these systems were aware that multiple health care staff, for example, therapy, medicine, and nursing were adding to a pile of information to be sent with the patient upon discharge. Staff stated that the discharge packet was generally 60–80 pages long and that they had little understanding of what information was actually contained in the packet.

Because this paper discharge information accompanied the patient to the SNF, the timeframe for SNF staff to review and clarify orders prior to the patient’s arrival was extremely limited. Further, physicians in Fragmented Systems did not directly contact the SNF physician of record and were unsure how or whether the next physician received the paper-based information they sent.

Interviewer: “How does the discharge summary get to the next physician”?

Response: “We don’t know that. We just send the discharge summary to the nursing home.” (Focus Group 10, MD 3)

Achieving the Discharge Plan

Integrated System

The overall goal in Integrated Systems was making the discharge a smooth and safe transition for all involved. Integrated Systems relied on interrelated processes that involved supporting the SNF, bridging care, and feedback and accountability to organize the discharge plan.

Because providers in Integrated Systems were aware of the capacities and limitations of SNFs and communicated on a regular basis about care processes, providers understood that supporting the SNF in carrying out the discharge plan was a requirement for safe and smooth transitions. Within the hospital, physicians who practiced in a team started the patient’s discharge plan prior to ending their rotation so that the oncoming physician would be aware of patient’s needs; this was particularly important if a patient had a lengthy or complex hospital stay. Integrated Systems ensured SNFs had all information necessary about the plan in advance of discharge and that the SNF staff could immediately implement the plan of care when the patient arrived.

“So there’s 3–4 hours for the nurses to review everything on the discharge summary before the patient is sent.” (Focus Group 1, Nurse 2)

In some cases, transfers were delayed by several hours or other hospital departments provided services temporarily to assist the SNF. For example, in one Integrated System, the hospital pharmacy prepackaged needed medications and sent them with the patient to avoid any delay in medication administration after the patient arrived at the SNF.

Integrated Systems used bridging as a strategy to increase quality of care for patients and improve working relationships with SNFs. Bridging involved the hospital physician providing 24–48 hr of direct postdischarge support to the SNF for any questions related to the care patients received, medications, discharge orders, or the patient’s clinical status.

“We take calls from the SNF, especially within the next 24–48 hours after discharge.” (Focus Group 12, MD 2)

Bridging was seen as critical to ensuring a safe transition until the physician in the community was prepared to accept and/or resume care of the patient. Physicians in Integrated Systems bridged care by providing SNF nurses with their cell phone numbers so they could contact them directly.

Another distinguishing feature of Integrated Systems was an investment in soliciting feedback from patients, SNF, and community physicians about discharge processes and a feeling of accountability for patient outcomes postdischarge. Staff and administrators in Integrated Systems sought out feedback formally through monthly meetings between hospital and SNF staff, and informally when SNF staff or the patient’s primary care physician came to the hospital to evaluate patients transitioning to the SNF. Providers stated that feedback was an essential step in helping them improve their process of transitioning patients.

“We meet monthly and talk about any problems we are having and we fix the problems.” (Focus Group 1, Nurse Administrator 1)

“Feedback from the community and physicians is critical to help us improve our process” (Focus Group 12, MD 5).

Staff in Integrated Systems, especially physicians, also described feeling accountable to patients, and often used the phrase ‘my patient’ when describing how they transitioned care. Physicians in these systems described in detail their knowledge of the patient both before and during the hospital stay. They used this knowledge to assess how well the patient would transition to the SNF environment. Nurses described having unique knowledge of patient idiosyncrasies, for example, how to calm agitation or patient preferences for food or medication administration, and feeling it was essential to share that information with SNF staff to make their work easier and care of the patient seamless. Staff also felt it was essential to prepare families in advance for the SNF setting by encouraging a pre-visit with the SNF to clarify expectations about care and reduce anxiety.

“When they know they’re being discharged the next day, they will schedule a meeting before so they [family] can go over there and see exactly where their loved one is going to be.” (Focus Group 2, Nurse 4)

Fragmented System

Staff in Fragmented Systems defined success as rapid movement of patients out of the hospital, opening beds, and ending care. Because of this, Fragmented Systems relied on parceling out and dividing the labor of discharge, practicing in silos/within a silo and ending care at discharge with little knowledge of whether or not the discharge plan was effective or safe.

Staff in Fragmented Systems often described working in silos/within a silo. Interaction among acute care staff on issues related to the transition/discharge occurred only on an as-needed or reactive basis. Physicians in Fragmented Systems stated they had little time or incentive to work with the SNF or work with other nonphysician hospital staff to plan discharge.

“We have tried to start interdisciplinary rounds, but our hospitalists refuse to participate.” (Focus Group 9, Case Manager 1)

Nurses stated they only contacted physicians if there was an error in the discharge summary or if they were concerned about the patient’s readiness to discharge. Some physicians in Fragmented Systems viewed nurses as being helpful in catching such errors, while others viewed nurses as “trying to block [their] plans for moving the patient out.” (Focus Group 10, MD 1)

In Fragmented Systems, the case manager was viewed as a key person in ensuring a quick discharge to a SNF. Both physician and nursing staff funneled information to case managers to relay to the SNF. In turn, case managers sought out individual hospital staff daily for relevant patient information requested by the SNF. At times, hospital physicians provided case managers very little time to prepare for a discharge and hospital nurses were unaware that patients were leaving that day.

“We pushed the case a little bit to see if they [case manager] could find a place.” (Focus Group 10, MD 5)

“I come on my shift and I find out my patient is leaving that day, now I have to do the paperwork and I don’t really know this person” (Focus Group 8 RN 3)

In Fragmented Systems, care ended when the patient left the hospital. Typically, participants described no attempts to bridge care, no feelings of accountability for the patient’s welfare, and/or no interest in feedback about transitions. When contact between SNF and hospital staff did occur, it was typically limited to questions about discharge medications. If SNF staff raised nonmedication questions, physicians in Fragmented Systems directed SNF nurses to contact the patient’s primary care physician in the community.

“They call us about medications, all other questions we tell them to call the physician that is going to take care of them in the nursing home.” (Focus Group 10, MD 7)

Nurses in Fragmented Systems stated they frequently received phone calls from SNF nurses with questions after 3 p.m. when the nurse who discharged the patient had often left. When this occurred, hospital nurses directed SNF nurses to either (a) call back the next day or (b) look more closely in the discharge paperwork sent from the hospital for answers to their questions.

“The nursing home will call back and I tell them it’s in the information I sent you, go look at that.” (Focus Group 8, RN 2)

Strategies for Improving the Transition

Acute care providers primarily in Integrated Systems offered several strategies for improving transitions between hospitals to SNF settings (Table 2). Because these providers valued feedback regarding transitional care, they actively collaborated with SNFs to identify areas for improvement, develop strategies to address gaps, and continually evaluate the process. Strategies were developed to address major problems identified by both hospital and SNF staff encompassing continuity and accuracy of patient information, poor transitional experience of patients and families, and negative relationships with SNF staff. Actions centered on instituting real time direct interdisciplinary and intersetting communication and systematically preparing patients and families for transition to the next care environment.

Table 2.

Improving the Transitional Care Process

| Problem identified | Solution or action taken | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Mismatch of clinical information among acute care providers which impeded the transition | • Institute daily communication among health care providers (MD, RN, SW, CM/DP, rehabilitation services) that focused on patient progress | • Well-rounded discharge plan that included content from all acute care providers |

| • Other health care providers (RN, rehabilitation services) felt more engaged in the transition process | ||

| • Implement daily care team rounds to update discharge plan and discuss transition | ||

| • Keep care team rounds focused to allow all providers sufficient time to discuss ongoing patient concerns and progress | ||

| Poor communication between hospital and SNF staff and community primary care MD leading to frequent call backs from SNF to clarify patient information | • Institute acute care RN to SNF RN handoff at time of transfer | • Decrease call backs from SNF to clarify patient information and discharge orders |

| • Institute acute care RN call to SNF 1–2 days before transfer to discuss patient clinical status and care needs | ||

| • Sense of improved communication and support for SNF setting | ||

| • Collaborate with SNF staff to create a patient information transfer sheet that is used by SNF when they transfer patients to the hospital and hospital when they transfer patients to SNF | • Improved smooth transition from hospital to SNF | |

| • Acute care MD report community physicians greatly appreciated updates on their patients and notification of pending diagnostics | ||

| • Institute acute care MD to SNF MD or community primary care provider handoff at time of transfer | ||

| Increased patient and family anxiety about the transition because of limited knowledge of SNF environment | • Institute patient/family care conference early during hospital admission to discuss discharge to SNF | • Patient and family members had time to prepare for transition to SNF setting |

| • Acute care providers reported families expressed appreciation for seeing SNF site before patient was transferred; decreasing their concerns and anxiety | ||

| • Family members encouraged to visit SNF before patient is admitted | ||

| • Increase acute care provider knowledge of SNF environment by providing onsite training in a SNF setting | ||

| • Nursing and medical staff able to answer patient and family questions about SNF setting | ||

| Poor relationship with SNF staff | • Institute monthly meetings between hospital and SNF administration to discuss issues or concerns with transitions that occur between settings | • Improved working relationship with SNF settings |

| • Improved process for transitioning patients to and from hospital to SNF settings | ||

| • Institute 24–48 hr bridge coverage for patients transitioning to SNF setting | ||

| • Quick response to SNF nurse call which decreased delay in addressing patient problem | ||

| • Provide physician phone access to SNF nurses |

Note: CM, case manager; DP, discharge planner; MD, medical doctor; RN, registered nurse; SNF, skilled nursing facility; SW, social work.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the depth, intensity, and goal of transitional care actions reported by hospital staff varied considerably based upon whether they were functioning in an Integrated or Fragmented System. This study helps shed light on the potential impact pre-existing health system contexts can have on transitional care processes, and how features of hospital context impact staff practices surrounding transitional care for SNF patients. While staff in both systems described feeling pressure to discharge patients quickly, those in Integrated Systems described more collaborative, patient-centered care, and a greater sense of accountability for care throughout the transition period. Staff in Integrated Systems expressed awareness of SNF needs and limitations and regularly received feedback about the quality of the transition. Knowledge and feedback were seen as fundamental to their systems’ integrated nature. In contrast, staff in Fragmented Systems stated their primary goal was to “get the patient out” and described less accountability, awareness, or feedback surrounding the transition. Quick movement of patients coupled with working in silos may impact the quality of information provided to the next care setting. This finding is consistent with other research that identified negative effects on the transition process when priority is placed on moving patients out quickly and when deficient information is provided (Hesselink et al., 2013; King et al., 2013).

The lack of awareness or accountability for transitional care described by providers in Fragmented Systems is consistent with previous research on SNF staff perspectives of transitions. King and coworkers (2013) identified multiple deficiencies in quality of information SNF nurses receive on patients transitioning from hospital to SNF from acute care providers. Poor quality communication was a major barrier to achieving a safe and smooth transition for patients and had negative consequences for family members and SNF staff. Achieving a successful handoff is critical for optimal outcomes for patients transitioning from hospital settings (Anderson & Helms, 1995; Coleman, 2003; Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine Report, 2001). Use of real-time, bidirectional communication has been identified as a necessary step to improving transitions from hospital to SNF (Herndon, Bones, Kurapati, Rutherford, & Vecchioni, 2012). “Warm handoffs” of time sensitive information between hospital providers (physicians and nurses) to SNF staff (nurses) and community provider (primary care physicians) has been recognized as a critical element to achieving high quality and safe transition of care for older adults (Ouslander et al., 2016). In our study, Integrated Systems identified that lack of two-way, timely communication between direct care providers created poor quality care transitions and jeopardized outcomes for older adult patients and their relationship with SNFs and primary care physicians in the community. Instituting a change in how, by whom, and when information regarding the patient was communicated was viewed as priority and resulted in a shift in their process of transitioning care between care systems.

Findings from this study would suggest that establishment of feedback loops across health care settings is essential for improving the transition process. Genuine intersetting staff relationships may facilitate a sense of accountability for how both action and inaction impact care beyond the hospital. Developing cross-continuum teams have been recommended by others to shift care focus from site specific to patient centered and to use intersetting communication to continuously improve the process of transitions from the perspective of the patient (Coleman, 2009; Herndon et al., 2012). Our findings support the importance of teamwork to improve care transitions. Providers in Integrated Systems understood the critical need to solicit feedback from patients, family members, community providers, and SNF staff as to how to improve the process of transitioning care between settings. Because they worked together as a team, they were able to improve the quality and safety of patient care by making small but effective changes in how they transitioned care between health care settings. One critical change our participants emphasized was the need for frequent and timely verbal handoff communication between direct care providers from the hospital to SNF staff and providers. During these handoff exchanges, acute care providers were able to determine if the SNF staff or community physician was ready to care for the patient, address any questions regarding the patients status, pass along unique information about patient and family needs that may not be reflected in the discharge summary and felt they were building a relationship with the SNF staff and community physicians because they knew who they were. The importance of handover communication has been identified as a necessary component in improving hospital to SNF transitions (Herndon et al., 2012). The critical need to build collaborations among health care providers and between health care settings (hospital to SNF) to improve transitional care has been identified in the literature (Carnahan, Unroe, & Torke, 2016; Coleman, 2003; Herndon et al., 2012; Kripalani, Jackson, Schnipper, & Coleman, 2007). Our study highlights key strategies used by Integrated Systems to build relationships and collaborations among health care providers and between health care settings. These include instituting daily care team rounds where all members contribute to the discussion of how the patient is progressing, direct care provider handoffs to promote two-way communication, engaging patients and family members early in the planning of transitioning care from the hospital to SNF, and implementing monthly working meetings between hospital and SNF to address concerns early and develop an effective plan. Strategies utilized by our participants provide “real-world” evidence that could be used to build effective interventions to improve transitioning care between hospital to SNF settings.

These results should be considered in light of several limitations. Our sample represented providers working in hospitals serving Midwestern rural communities, which may not be generalizable to other populations. Our results may not be consistent with other types of care transitions, that is, non-SNF transitions. Finally, since staff were not directly observed, therefore we are unable to confirm the actual hospital discharge procedures reported by participants. However, our results provide valuable insight into shared beliefs and assumptions of multiple health care providers. Findings from this study can inform development of clinical interventions based in real-world experience related to transitional care.

In conclusion, the hospital system and its Integrated versus Fragmented nature exerts an influence on staff’s perception of role, process, and goals during hospital to SNF transitions. These system contextual influences will be critical to consider in designing future system-level interventions to improve health system coordination.

Funding

A. J. H. Kind’s time was supported by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program. The project was supported by the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics, a National Institute on Aging Beeson Career Development Award (K23AG034551 [PI: A. J. H. Kind]), National Institute on Aging, The American Federation for Aging Research, The John A. Hartford Foundation, The Atlantic Philanthropies, The Starr Foundation, National Institute on Aging 2P50AG033514-06, and by the Madison VA Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC-Manuscript #2015-008). The material is also the result of work supported with resources and facilities at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital.

References

- Anderson M. A., & Helms L. B (1995). Communication between continuing care organizations. Research in Nursing and Health, 18, 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers B., & Schatzman L. Dimensional analysis. (2009). In Morse J., Stern P., Corbin J.et al. (Eds.), Developing grounded theory: The second generation (pp. 86–126). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan J. L. Unroe K. T., & Torke A. M (2016). Hospital readmission penalties: Coming soon to a nursing home near you!Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64, 614–618. doi:10.1111/jgs.14021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron C., & Bowers B (2000). Methods and application of dimensional analysis: A contribution to concept and knowledge development in nursing. In B. L., Rodgers, K. A., Knafl (Eds.), Concept development in nursing, foundations, techniques and applications (pp. 285–319). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E. A. (2003). Falling through the cracks: Challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 549–555. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E. A. (2009). Safety in numbers: Physicians joining forces to seal the cracks during transitions. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 4, 329–330. doi:10.1002/jhm.548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine.(2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system of the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., & Strauss A (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Herndon L. Bones C. Kurapati S. Rutherford P., & Vecchioni N (2012). How-to-guide: Improving transitions from the hospital to skilled nursing facilities to reduce avoidable rehospitalizations. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; Retrieved December 2, 2015, from www.IHI.org. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselink G. Vernooij-Dassen M. Pijnenborg L. Barach P. Gademan P. Dudzik-Urbaniak E., … Wollersheim H; European HANDOVER Research Collaborative (2013). Organizational culture: An important context for addressing and improving hospital to community patient discharge. Medical Care, 51, 90–98. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827632ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind A. J. Thorpe C. T. Sattin J. A. Walz S. E., & Smith M. A. (2012). Provider characteristics, clinical-work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub-acute care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27, 78–84. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1860-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King B. J. Gilmore-Bykovskyi A. L. Roiland R. A. Polnaszek B. E. Bowers B. J., & Kind A. J (2013). The consequences of poor communication during transitions from hospital to skilled nursing facility: A qualitative study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61, 1095–1102. doi:10.1111/jgs.12328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kools S. McCarthy M. Durham R., & Robrecht L (1996). Dimensional analysis: Broadening the conception of grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 6, 312–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kripalani S. Jackson A. T. Schnipper J. L., & Coleman E. A (2007). Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: A review of key issues for hospitalists. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2, 314–323. doi:10.1002/jhm.228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V. Intrator O. Feng Z., & Grabowski D (2010). The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Affairs, 29, 57–64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. Stern P. Corbin J. Bowers B. Charmaz K., & Clarke A (2009). Developing grounded theory: The second generation. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ouslander J. Naharci I. Engstrom G. Shutes J. Wolf D. Rojido M., … Newman D (2016). Hospital transfers of skilled nursing facility (SNF) patients within 48 hours and 30 days after SNF admission. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17, 839–845. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2016.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polnaszek B. Mirr J. Roiland R. Gilmore-Bykovskyi A. Hovanes M., & Kind A (2015). Omission of physical therapy recommendations for high-risk patients transitioning from the hospital to subacute care facilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95, 1966–1972. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L. (1991). Dimensional analysis: Notes on an alternative approach to grounding of theory in qualitative research. In D. R., Maines (Ed.), Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss (pp. 303–314). New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Snow V. Beck D. Budnitz T. Miller D. C. Potter J. Wears R. L., … Williams M. V (2009). Transitions of care consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 4, 364–370. doi:10.1002/jhm.510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. (2003). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walz S. E. Smith M. Cox E. Sattin J., & Kind A. J (2011). Pending laboratory tests and the hospital discharge summary in patients discharged to sub-acute care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 393–398. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1583-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]