Abstract

Procaterol hydrochloride hydrate (procaterol) is a β2‐adrenergic receptor agonist that induces a strong bronchodilatory effect. The procaterol dry powder inhaler (DPI) has been frequently used in patients with bronchial asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. We evaluated the bioequivalence and safety between the new procaterol DPI (new DPI) and the approved procaterol DPI (approved DPI). This study was a randomized, double‐blind, double‐dummy, crossover comparison to evaluate the pharmacodynamic equivalence of the new DPI and the approved DPI in patients with bronchial asthma. Primary efficacy variables were area under the concentration‐time curve (AUC) forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 during the 480‐minute measurement period. Patients were divided into 2 groups, New‐DPI‐First (n = 8) and Approved‐DPI‐First (n = 8), according to the investigational medical product that was administered first. Patients inhaled 20 μg of procaterol in each period. FEV1 was measured by a spirometer at predose and at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 360, and 480 minutes after each investigational medical product administration. Equivalence was evaluated by confirming that the 2‐sided 90%CIs for the difference between the new and the approved DPI in means of AUC (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 were within the acceptance criteria of –0.15 to 0.15 L. The difference in means of AUC (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 was 0.041 L and 0.033 L, respectively, and the 90%CI was 0.004 to 0.078 L and –0.008 to 0.074 L, respectively. These CIs were both within the acceptance criteria. The new DPI was assessed as being bioequivalent to the approved DPI.

Keywords: pharmacodynamic equivalence, dry powder inhaler, procaterol, asthma, device

Inhaled drugs are the most common and effective therapy in the management of bronchial asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Short‐acting β2‐agonists are known as rescue or relief medications for asthma or COPD symptoms. Procaterol hydrochloride hydrate (8‐hydroxy‐5‐{(1RS,2SR)‐1‐hydroxy‐2‐[(1‐methylethyl)amino]butyl}quinolin‐2(1H)‐one monohydrochloride hemihydrate) is a β2‐adrenergic receptor agonist synthesized by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, in 1973. It binds highly selectively to β2‐adrenergic receptors in bronchial smooth muscle cells, and a small dose of this drug induces a strong bronchodilatory effect.1, 2 A variety of formulations have been developed for this drug since the first launch of its tablet formulation in 1980. Currently marketed formulations including dry powder inhaler (DPI) and pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) have been clinically useful, mainly in Asia. The effects of these inhalants are immediate, providing a good adaptation for sudden or new symptoms of asthma or COPD.

DPIs are easier to use than pMDIs because there is no need to coordinate actuation and inhalation. In addition, because DPIs do not contain environmentally unfriendly propellants,3 it is thought that DPIs are adaptive to future global environmental regulations. However, DPIs are available in many different designs, and DPIs that require many operational steps may mislead patients to inadequate inhalation of the drug. It is obvious that incorrect usage of inhaler devices has a considerable influence on the clinical effectiveness of the delivered drug.3 Clickhaler® (an approved DPI device) has hallmarked the effective uniformity and consistency of the delivered dose and fine particle fraction over a range of inspiratory flow rates4; however, patients are required to perform several steps to inhale the drug. To improve this, a new DPI, Swinghaler® (a new DPI device) was designed that requires no shaking to dispense the correct volume of powder into the measuring cups prior to inhalation, thus reducing the operational steps, and is easier to use.5, 6 In addition, the powder inhaler and storage container of the new DPI device are integrated, making it a smaller device, which greatly improves the portability of the drug. These features are considered to be beneficial to patients, and Meptin®Swinghaler® (new DPI) is expected to ease patients’ treatment. The new DPI was granted approval in 2014 in Japan and is currently the only DPI of short‐acting β2‐agonists launched in Japan.6

The bioequivalence between the new DPI and the approved DPI in patients was unknown. Although there are no standardized methods to demonstrate in vivo bioequivalence of inhaled bronchodilators, the most practical method of showing therapeutic equivalence in vivo is by estimating their relative potencies in clinical efficacy studies using adequate methodology of comparing their bronchodilator actions.7 Hence, this study was conducted to evaluate the bioequivalence and safety between the new DPI (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Tokushima, Japan) and the approved DPI (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Tokushima, Japan) in patients with bronchial asthma.

Methods

Study Design

This study was designed as a randomized 2‐treatment, 2‐period, double‐blind, double‐dummy, crossover comparison phase 3 study using FEV1 as an index of bronchodilator effect to evaluate the pharmacodynamic equivalence between the new DPI and the approved DPI in adult patients with bronchial asthma. According to the guidelines for bioequivalence studies of generic products,8, 9, 10, 11, 12 1 dose unit or a normally used clinical dose should generally be employed, and it should generally be given in a single dose. The dose was determined to be 20 μg of procaterol, which is the adult dose of the approved DPI. Primary efficacy variables were area under the concentration‐time curve (AUC) (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 during the 480‐minute measurement period.

Treatment duration was divided into periods 1 and 2 with a washout interval of 1 day to 4 weeks between the 2 periods. Patients were grouped into 2 groups, New‐DPI‐First group (8 patients) and Approved‐DPI‐First group (8 patients), based on the starting investigational medical product (IMP). Further, in each period, each preceding group was divided into 2 drug sequence groups, 1 in which an active drug was administered first, followed by placebo, and the other in which placebo was administered first, followed by the active drug. Patients were randomly assigned to the 4 drug sequence groups. Patients inhaled 20 μg of procaterol in each period, under supervision of the investigator or subinvestigator. To maintain blinding, each IMP was supplemented with a matching placebo, so that a total of 4 puffs (2 puffs of active drug and 2 puffs of placebo) were taken in each period. The 4 drug sequence groups were employed in randomization to achieve a balanced administration design: A and B (New‐DPI‐First group), which received the new DPI in period 1 and the approved DPI in period 2, and C and D (Approved‐DPI‐First group), which received the opposite combination. Groups A and C received the active drug during the first administration in each periods, and groups B and D received it in the opposite order (Supplemental Figure 1S).

Study Procedures

This study was conducted at the General Clinical Research Center of Oita University Hospital from March to June, 2012, in compliance with the ethical principles originating from the Declaration of Helsinki, the Pharmaceutical Affairs Law, the Japanese Ministerial Ordinance on Good Clinical Practice (MHW Ordinance number 28 dated Mar 27, 1997) and related notifications, and with the protocol. Prior to the study, all patients were given explanations of the details of the study using written information approved by the Institutional Review Board of Oita University Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Patients diagnosed with bronchial asthma who met the following inclusion criteria were eligible to enter the study:

Patients aged 20 years or older at the time of informed consent.

Patients who have used MDIs or DPIs.

Patients who were receiving either inpatient or outpatient treatment.

Patients whose initial FEV1 values were 40% or higher than the predicted FEV1 value.

Patients whose FEV1 had improved by 12% or more and increased by 200 mL or more (absolute amount) after inhalation of a β2 agonist (procaterol pMDI).

However, patients were excluded who had been treated in an emergency room or hospitalized due to acute exacerbations of asthma symptoms within 3 months or received steroid drugs other than inhaled steroids or anti‐IgE antibodies within 4 weeks prior to the start of this study, who had participated in other clinical study, or had much blood collected, a history of hypersensitivity to β2 agonists, hypokalemia, pregnancy, or a respiratory tract infection.

Concomitant use of inhaled steroids was permitted only if regular dosing had been started 4 weeks prior to the screening examination; however, the dosage and dosing regimen were not allowed to be changed during the study period. Other therapeutic medications for asthma were prohibited prior to the screening examination and study period. Patients whose initial FEV1 values were 40% or higher than the predicted FEV1 values were selected in order to coordinate patients with similar levels of respiratory function. After confirming that the FEV1 values were within the range of 88% to 112% of the initial FEV1 before the IMPs were inhaled in period 1, IMPs in ascending drug number order were allocated to patients who met the inclusion criteria on the basis of earlier assignment. Drug numbers were allocated to the 4 drug sequence groups in accordance with the random allocation table provided by the controller. In period 2, if FEV1 value before IMP administration was not within the range of 88% to 112% of the FEV1 value measured before IMP administration in period 1, the other planned investigations and tests were not performed. The investigations and tests were repeated again within 1 day to 4 weeks after IMP administration in period 1. In both periods, FEV1 was measured.

Patients continued to be allocated to the groups until all 16 patients completed all of the doses, investigations, and examinations in periods 1 and 2. The sample size was calculated by applying the Schuirmann 2 1‐sided test procedure13 to the error variance obtained from the previous clinical study of the approved DPI and procaterol pMDI.14

Pulmonary Function Test

Measurement of Initial FEV1 Values and Airway Reversibility Test

FEV1 was measured by a spirometer after the patient remained at rest for 5 minutes. Patients inhaled 20 μg of procaterol pMDI during the airway reversibility test, and FEV1 was measured at 30 minutes ± 5 minutes. The relative improvement and absolute improvement over the initial FEV1 value were calculated, and patients who met the inclusion criteria (improvement by 12% or more and an increase of 200 mL or more [absolute amount]) were selected.

Measurement of FEV1 in Period 1 and Period 2

In both periods, FEV1 was measured by a spirometer after the patient had remained at rest for 5 minutes at predose and at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 360, and 480 minutes after each IMP administration.

Blinding

This was a double‐blind study. The person responsible for IMP allocation prepared the Random Allocation Table (allocation table) and coded the IMP in accordance with the procedure for allocation. The allocation table was sealed by the person responsible for IMP allocation immediately after completion of IMP allocation and stored under lock and key until unblinding following the finalization of all case report forms and databases.

Statistical Methods

The purpose of this study was to verify that the new DPI is pharmacodynamically equivalent to the approved DPI by confirming that the 2‐sided 90%CIs for the differences between the new and the approved DPIs in mean AUC (FEV1)/h and mean maximum FEV1 were within the acceptance criteria of –0.15 to 0.15 L. Each parameter was calculated using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The peak FEV1 was the maximum FEV1 value during the 480‐minute measurement period. The AUC (FEV1)/h, which was area under the curve per unit time calculated by the trapezoidal method based on measured FEV1 values at each time point from the former value, was a value obtained by dividing the AUC (FEV1)480min by 8. For the calculation, the actual postdose times for measurements were used instead of the postdose times specified in the protocol. AUC (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Variance analysis was conducted for the following factors: groups (new‐DPI‐first group and approved‐DPI‐first group), drugs (new DPI and approved DPI), patients in the groups, and time points. From the error variance obtained from the analysis, the difference in the mean values between the new and the approved DPIs as well as 2‐sided 90%CI were obtained.

Safety Analysis

Adverse events and potentially drug‐related treatment‐emergent adverse events were classified by system organ class and preferred term using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities/Japanese version (MedDRA/J) version 15.0, and the number of patients who developed them, incidence rate, and number of episodes were obtained for each of the events and totaled.

Descriptive statistics were obtained for actual measured values at each time point and for changes from predose values for quantitative items of laboratory tests and vital signs of blood pressure, pulse rate, and body temperature. Blood sampling and urine collection for clinical laboratory tests were performed at the screening examination and before and 480 minutes after inhalation in each period. Twelve‐channel electrocardiogram was performed before the screening examination and before and 480 minutes after inhalation in each period. Vital signs were measured before the airway reversibility test at the screening examination and before and 30, 60, and 480 minutes after inhalation in each period.

Results

Disposition of Patients

The disposition of patients is shown in Supplemental Figure S2. Informed consent was obtained from 49 patients; however, 1 patient withdrew consent, and 48 patients underwent the screening examination. Sixteen out of 48 patients were judged to be eligible based on the results of the screening examination. The IMPs were allocated and administered to the New‐DPI‐First and the Approved‐DPI‐First groups. All 16 patients completed the study.

Background of Patients

The demographics and other baseline characteristics of patients in the pharmacodynamics analysis are shown in Table 1. The mean ± SD values for age, height, and weight of the pharmacodynamic and safety analysis sets combining both the New‐DPI‐First and the Approved‐DPI‐First groups were 49.0 ± 14.8 years, 163.3 ± 7.6 cm, and 66.0 ± 13.7 kg, respectively. The mean ± SD duration of disease of the New‐DPI‐First and the Approved‐DPI‐First groups were 14.5 ± 12.2 years and 14.4 ± 16.2 years, respectively. There were no patients with severe bronchial asthma in either group.

Table 1.

Demographics and Other Baseline Characteristics of Patients in the Pharmacodynamic Analysis Set

| New‐DPI‐First Group (n = 8) | Approved‐DPI‐First Group (n = 8) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Total | % | Number of Patients | % | Number of Patients | % | |

| Sex | Male | 8 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 |

| Female | 8 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | 4 | 50.0 | |

| Age (y) | <65 | 14 | 87.5 | 6 | 75.0 | 8 | 100.0 |

| ≥65 | 2 | 12.5 | 2 | 25.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Duration of disease (y) | <3 | 4 | 25.0 | 1 | 12.5 | 3 | 37.5 |

| ≥3 and <5 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| ≥5 and <10 | 2 | 12.5 | 1 | 12.5 | 1 | 12.5 | |

| ≥10 and <20 | 5 | 31.3 | 3 | 37.5 | 2 | 25.0 | |

| ≥20 and <30 | 1 | 6.3 | 1 | 12.5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| ≥30 | 3 | 18.8 | 1 | 12.5 | 2 | 25.0 | |

| Type of disease | Atopic | 6 | 37.5 | 4 | 50.0 | 2 | 25.0 |

| Nonatopic | 10 | 62.5 | 4 | 50.0 | 6 | 75.0 | |

| Severity | Mild | 5 | 31.3 | 4 | 50.0 | 1 | 12.5 |

| Moderate | 11 | 68.8 | 4 | 50.0 | 7 | 87.5 | |

| Severe | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

DPI indicates dry powder inhaler.

Pulmonary Function

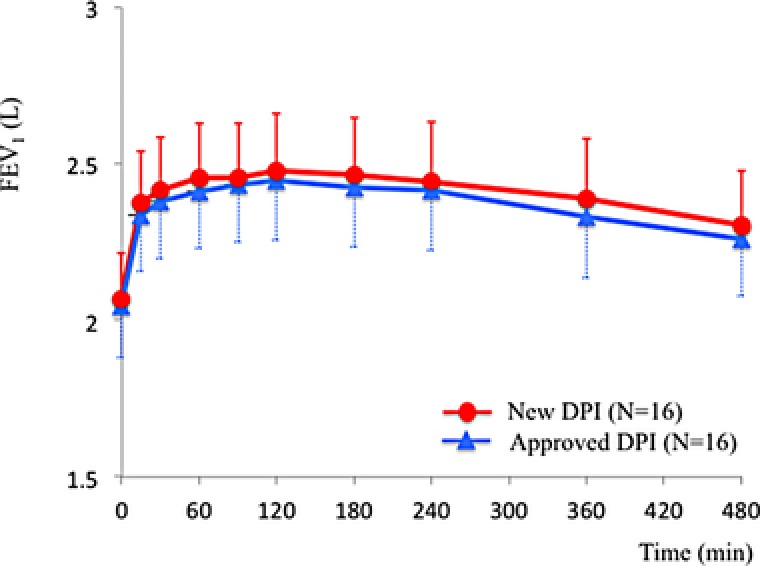

FEV1‐time profiles after administration of the new DPI or the approved DPI in the pharmacodynamic analysis set are shown in Figure 1. For both DPIs, peak FEV1 was obtained 120 minutes after administration, and the mean ± SD peak FEV1 was 2.48 ± 0.73 L for the new DPI and 2.45 ± 0.76 L for the approved DPI. The difference in peak FEV1 between the 2 DPIs was 0.03 ± 0.11 L. The FEV1 of both DPIs gradually decreased after the peak until the final measurement points at 480 minutes after administration.

Figure 1.

FEV1‐time profiles after administration of New DPI (red circle) or Approved DPI (blue triangle). Error bars represent standard deviations.

The mean ± SD AUC (FEV1)/h was 2.41 ± 0.73 L for the new DPI and 2.37 ± 0.75 L for the approved DPI. The mean of differences in AUC (FEV1)/h between the 2 DPIs was 0.04 ± 0.09 L (Table 2). The mean ± SD maximum FEV1 was 2.53 ± 0.74 L for the new DPI and 2.50 ± 0.75 L for the approved DPI. The mean of differences in maximum FEV1 between the 2 DPIs was 0.03 ± 0.09 L (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of AUC (FEV1)/h and Maximum FEV1 After Administration of New DPI or Approved DPI

| Parameter | Administered Drug | Number of Patients | Mean | SD | Minimum | Median | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (FEV1)/h | New DPI | 16 | 2.41 | 0.73 | 1.28 | 2.28 | 4.09 |

| Approved DPI | 16 | 2.37 | 0.75 | 1.23 | 2.23 | 4.28 | |

| Difference between the 2 DPIsa | 16 | 0.04 | 0.09 | ‐0.19 | 0.05 | 0.17 | |

| Maximum FEV1 | New DPI | 16 | 2.53 | 0.74 | 1.51 | 2.41 | 4.21 |

| Approved DPI | 16 | 2.50 | 0.75 | 1.54 | 2.34 | 4.38 | |

| Difference between the 2 DPIsb | 16 | 0.03 | 0.09 | ‐0.17 | 0.02 | 0.19 |

Data are expressed in liters. AUC indicates area under the FEV1‐time curve; DPI, dry powder inhaler; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

New DPI AUC (FEV1)/ h – Approved DPI AUC (FEV1)/ h.

New DPI maximum FEV1 – Approved DPI maximum FEV1.

Results of ANOVA showed no significant group or carryover effects for either AUC (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 (P = .50 and P = .59, respectively), and no significant period effects for either AUC (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 (P = .19 and P = .42, respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Variance Analysis Table for AUC (FEV1)/h and Maximum FEV1

| Factor | Degrees of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | Variance Ratio | P‐Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (FEV1)/ha | Interpatient | Group or carryover effects | 1 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.48 | .50 |

| Patient/group | 14 | 15.74 | 1.12 | 317.95 | <.001 | ||

| Intrapatient | Time point | 1 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 1.92 | .19 | |

| DPI | 1 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 3.71 | .08 | ||

| Residual error | 14 | 0.049 | 0.004 | ||||

| Total variation | 31 | 16.34 | |||||

| maximum FEV1 b | Interpatient | Group or carryover effects | 1 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.30 | .59 |

| Patient/group | 14 | 16.12 | 1.15 | 267.99 | <.001 | ||

| Intrapatient | Time point | 1 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.70 | .42 | |

| DPI | 1 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 2.04 | .18 | ||

| Residual error | 14 | 0.06 | 0.004 | ||||

| Total variation | 31 | 16.54 | |||||

New‐DPI mean value = 2.41 L; Approved‐DPI mean value = 2.37 L; difference in the mean values = 0.04 L; 90%CI of the difference = 0.004 to 0.078 L.

New‐DPI mean value = 2.53 L; Approved‐DPI mean value = 2.50 L; difference in the mean values = 0.03 L; 90%CI of the difference = –0.008 to 0.074 L.

The difference in means of AUC (FEV1)/h and maximum FEV1 after administration of the new or the approved DPI was 0.04 L and 0.03 L (Table 2), respectively, and the 2‐sided 90%CI was 0.004 to 0.078 L and –0.008 to 0.074 L, respectively. Because the 2‐sided 90%CIs were within the range of –0.15 to 0.15 L, the new and the approved DPIs were determined to be pharmacodynamically equivalent, and it was confirmed that both DPIs were bioequivalent in accordance with the guidelines.

Safety

All patients received treatment with both the new and the approved DPIs during the study. There were no deaths or other significant adverse events. There were no significant clinical changes in laboratory tests or vital signs. There were no abnormal findings in 12‐channel electrocardiogram examination.

Discussion

DPIs and pMDIs are the most commonly used devices for drug delivery in the treatment of asthma and COPD. Drugs are mainly absorbed in the respiratory tract after being delivered by DPIs or pMDIs. Because both devices deliver local therapeutic agents that become effective when the drugs reach respiratory tract regions, the speed of delivery and amount of drugs entering the systemic blood circulation do not serve as indicators of therapeutic effects. The bioequivalence guidelines of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare stated that pharmacodynamic studies are to be carried out for drugs for which bioavailability does not serve as an indicator of therapeutic efficacy.8 Therefore, in this study, the bioequivalence of the new and the approved DPIs were evaluated using the effect on pulmonary function (FEV1) in 16 adult patients with bronchial asthma, in accordance with the guidelines and in reference to pharmacodynamic study results of the approved DPI.4 The pharmacodynamic equivalence was mainly assessed based on maximum FEV1 and AUC (FEV1)/h in previously conducted studies in Japan, and the pharmacodynamic equivalence between 2 medications of bronchodilators was determined to be within the acceptance criteria of –0.15 to 0.15 L in the 90%CI for the difference between treatments.10 Therefore, the same acceptance criteria were employed in this study. The American Thoracic Society stated that a 12% increase, which is calculated from the prebronchodilator value, and a 200‐mL increase in either forced vital capacity or FEV1 are reasonable criteria for a positive bronchodilator response in adults.15 The patients of this study had reversible airway obstruction, and their FEV1 improved by at least 12% and increased by at least 200 mL after inhalation of β2‐adrenergic receptor agonist, indicating that the patients’ enrollment was appropriate.

In this study the 90%CI for differences between the new and the approved DPIs were 0.004 to 0.078 L for mean AUC (FEV1)/h and –0.008 to 0.074 L for mean maximum FEV1, both within the acceptance criteria of –0.15 to 0.15 L. Therefore, both DPIs were confirmed to be pharmacodynamically equivalent, and it was confirmed that they were bioequivalent in accordance with the guidelines.

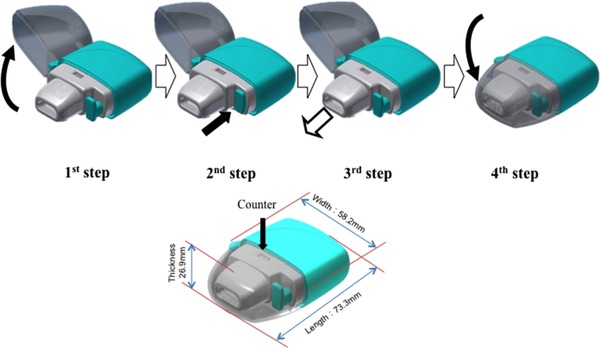

DPIs have been developed to make inhalation simpler as compared with pMDIs, without the need to coordinate inhalation and actuation.3 The new DPI only requires 4 operational steps for correct usage (1, open storage case; 2, push right side button; 3, inhale; 4, close storage case) (Figure 2), as compared to 7 steps for the approved DPI.6 Furthermore, the new DPI is smaller in size, which makes it easier for patients to carry around. In addition, DPIs do not contain environmentally harmful propellants, which is in line with the adoption of an amendment for gradual phase down of production and consumption of hydrofluorocarbons during the 28th meeting of the parties to the Montreal protocol on substances that deplete the ozone layer that was held in 2016. Also, the Paris agreement to prevent global warming went into effect in 2016 with an important theme on hydrofluorocarbon regulation. Therefore, usage of the new DPI is expected to increase as compared to pMDI in the future.

Figure 2.

Operation of the Swinghaler® DPI. First step: open storage case. Second step: push right side button. Third step: inhale. Fourth step: close storage. Counter shows the number of available inhalations remaining.

In conclusion, the evaluation of pharmacodynamic and safety properties in this study demonstrated that the new DPI was bioequivalent to the approved DPI. The new DPI was developed as a simpler device with fewer operational steps than the approved DPI. There were no clinically significant events that would suggest safety issues, and it was confirmed that there were no issues with the bioequivalence of the new and the approved DPIs. The new procaterol hydrochloride hydrate DPI is a useful and easy DPI for patients with bronchial asthma or COPD.

Supporting information

Supplemental Figure 1S: Clinical study flow diagram. New‐DPI‐First group (A and B) was given New‐DPI in period 1 and Approved‐DPI in period 2 for drug inhalation. Approved‐DPI‐First group (C and D) was given Approved‐DPI in period 1 and New‐DPI in period 2 for drug inhalation.

Supplemental Figure 2S: Disposition of patients. Sixteen patients were judged to be eligible for the study and all of them completed the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment and Funding

The authors would like to thank Dr Terumasa Miyamoto for medical advice. This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Osaka, Japan.

Author Contributions

J.K. and K.O. were medical advisers and provided suggestions on the study design, study conduct, and interpretation of data. R.S., Y.S., K.S., Y.T., I.T., and N.K. contributed to the study design, study conduct, and data analysis and interpretation. All authors listed were involved in the critical review and revision of the manuscript, and all provided final approval of the content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

J.K. received honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Co, Ltd, MSD, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Shionogi & Co, Ltd, Pfizer Japan Inc, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, and a payment for writing from Nankodo Co, Ltd, and research funding from Daiichi Sankyo Co, Ltd, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, MSD, Astellas Pharma Inc, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co. Ltd, and Mylan EPD Co, Ltd. N.K. is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Kume H. Clinical use of β2‐adrenergic receptor agonist based on their intrinsic efficacy. Allergol Int. 2005;54:89‐97. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kume H, Fukunaga K, Oguma T. Research and development of bronchodilators for asthma and COPD with a focus on G protein/KCa channel linkage and β2‐adrenergic intrinsic efficacy. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;156:75‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC, et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2008;102:593‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newhouse MT, Nantel NP, Chambers CB, Pratt B, Parry‐Billings M. Clickhaler (a novel dry powder inhaler) provides similar bronchodilation to pressurized metered‐dose inhaler, even at low flow rates. Chest. 1999;115:952‐956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fukunaga Y, Takahashi Y, Nishiguchi S, et al. Development of a patient oriented inhalation system—redesign of the Swinghaler® DPI. Respir Drug Deliv Eur. 2013;2:335‐338. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shirai R, Kadota J. Meptin®Swinghaler®. Kokyu [Respiration Research]. 2015;34(6):596‐602 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nair P, Hanrahan J, Hargreave FE. Clinical equivalence testing of inhaled bronchodilators. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2009;119:731‐734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Guideline for Bioequivalence Studies of Generic Products (PMSD/ELD Notification No. 487 dated December 22, 1997) and Partial revision of the Guideline for Bioequivalence Studies of Generic Products (PFSB Notification No. 1124004, dated 24 Nov 2006, and PFSB Notification 0229 No.10, dated 29 Feb 2012).

- 9. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Guideline for bioequivalence studies of generic products (in Japanese). http://www.nihs.go.jp/drug/be-guide/GL971222_BE.pdf. Published 1997. Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 10. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Guideline for bioequivalence studies of generic products (in Japanese). http://www.nihs.go.jp/drug/be-guide/GL061124_BE.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 11. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Partial revision of guideline for bioequivalence studies of generic products (in Japanese) and approval review of generic drugs in Japan. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000160026.pdf, http://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000163504.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 12. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Guideline for bioequivalence studies of generic products. http://www.nihs.go.jp/drug/be-guide(e)/Generic/GL-E_120229_BE_rev140409.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 13. Schuirmann DJ. A comparison of the two one‐sided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1987;15:657‐680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kawai M, Sakai A, Takaori S, et al. Pharmacodynamic study of procaterol hydrochloride dry powder inhaler: evaluation of pharmacodynamic equivalence between procaterol hydrochloride dry powder inhaler and procaterol hydrochloride pMDI in asthma patients in a randomized, double‐dummy, double‐blind crossover manner. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2005;27:385‐389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Medical Section of the American Lung Association . American Thoracic Society. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1202‐1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1S: Clinical study flow diagram. New‐DPI‐First group (A and B) was given New‐DPI in period 1 and Approved‐DPI in period 2 for drug inhalation. Approved‐DPI‐First group (C and D) was given Approved‐DPI in period 1 and New‐DPI in period 2 for drug inhalation.

Supplemental Figure 2S: Disposition of patients. Sixteen patients were judged to be eligible for the study and all of them completed the study.

Supplementary Material