Olanzapine has been shown to prevent chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting; however, evidence of differences between olanzapine‐based triple regimens and neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist‐based triple regimens is limited. This article compares the two antiemetic regimens and presents useful information for oncologists making decisions for the treatment of patients with chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting.

Keywords: Chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting, Highly emetogenic chemotherapy, Olanzapine, Neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists, Nausea, Network meta‐analysis

Abstract

Background.

The current antiemetic prophylaxis for patients treated with highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) included the olanzapine‐based triplet and neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists (NK‐1RAs)‐based triplet. However, which one shows better antiemetic effect remained unclear.

Materials and Methods.

We systematically reviewed 43 trials, involving 16,609 patients with HEC, which compared the following antiemetics at therapeutic dose range for the treatment of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: olanzapine, aprepitant, casopitant, fosaprepitant, netupitant, and rolapitant. The main outcomes were the proportion of patients who achieved no nausea, complete response (CR), and drug‐related adverse events. A Bayesian network meta‐analysis was performed.

Results.

Olanzapine‐based triple regimens showed significantly better no‐nausea rate in overall phase and delayed phase than aprepitant‐based triplet (odds ratios 3.18, 3.00, respectively), casopitant‐based triplet (3.78, 4.12, respectively), fosaprepitant‐based triplet (3.08, 4.10, respectively), rolapitant‐based triplet (3.45, 3.20, respectively), and conventional duplex regimens (4.66, 4.38, respectively). CRs of olanzapine‐based triplet were roughly equal to different NK‐1RAs‐based triplet but better than the conventional duplet. Moreover, no significant drug‐related adverse events were observed in olanzapine‐based triple regimens when compared with NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens and duplex regimens. Additionally, the costs of olanzapine‐based regimens were obviously much lower than the NK‐1RA‐based regimens.

Conclusion.

Olanzapine‐based triplet stood out in terms of nausea control and drug price but represented no significant difference of CRs in comparison with NK‐1RAs‐based triplet. Olanzapine‐based triple regimens should be an optional antiemetic choice for patients with HEC, especially those suffering from delayed phase nausea.

Implications for Practice.

According to the results of this study, olanzapine‐based triple antiemetic regimens were superior in both overall and delayed‐phase nausea control when compared with various neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists‐based triple regimens in patients with highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC). Olanzapine‐based triplet was outstanding in terms of nausea control and drug price. For cancer patients with HEC, especially those suffering from delayed‐phase nausea, olanzapine‐based triple regimens should be an optional antiemetic choice.

摘要

背景。目前针对高致吐性化疗 (HEC) 患者的止吐预防治疗包括含奥氮平的三联方案以及含神经激肽‐1 受体拮抗剂 (NK‐1RAs) 的三联方案。但是, 尚不清楚哪一种方案的止吐效果更佳。

材料和方法。我们系统回顾了 43 项试验, 涉及 16 609 名 HEC 患者, 这些试验比较了以下止吐剂在治疗剂量范围内对化疗所致恶心呕吐的治疗:奥氮平、阿瑞匹坦、卡索匹坦、福沙匹坦、奈妥匹坦和罗拉匹坦。主要结果是未出现恶心、完全缓解 (CR) 和发生药物相关不良事件的患者比例。我们进行了一项 Bayesian 网络荟萃分析。

结果。在全程和延迟期, 与含阿瑞匹坦的三联方案(比值比分别为 3.18、3.00)、含卡索匹坦的三联方案(分别为 3.78、4.12)、含福沙匹坦的三联方案(分别为 3.08、4.10)、含罗拉匹坦的三联方案(分别为 3.45、3.20)以及常规二联方案(分别为 4.66、4.38)相比, 含奥氮平的三联方案显示出的无恶心率显著更佳。含奥氮平的三联方案的 CR 大体等于不同的含 NK‐1RA 的三联方案, 但优于常规二联方案。而且, 与含 NK‐1RA 的三联方案以及二联方案相比, 未观察到含奥氮平的三联方案出现显著药物相关不良事件。此外, 含奥氮平的方案的费用明显低于含 NK‐1RA 的方案。

结论。在控制恶心和药物价格方面, 含奥氮平的三联方案表现突出, 但 CR 与含 NK‐1RA 的三联方案相比无显著差异。含奥氮平的三联方案应成为 HEC 患者(特别是出现延迟期恶心的患者)的一项止吐选择。

对临床实践的启示

根据本研究的结果, 在接受高致吐性化疗 (HEC) 的患者中, 含奥氮平的三联止吐方案在全程和延迟期恶心控制方面的表现优于多种含神经激肽‐1 受体拮抗剂的三联方案。在控制恶心和药物价格方面, 含奥氮平的三联方案表现突出。对于接受 HEC 的癌症患者(特别是出现延迟期恶心的患者), 含奥氮平的三联方案应成为一项止吐选择。

Introduction

Chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) are very common side effects that often discourage patients’ compliance with anticancer treatment and lead to a significant deterioration in quality of life [1], [2], [3]. Patients receiving chemotherapy, especially highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC), are the main population suffering from nausea and vomiting [4]. CINV can be classified as acute phase (0–24 hours after chemotherapy) or delayed phase (24–120 hours after chemotherapy) based on the time of incidence. Neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists (NK‐1RAs), a novel class of antiemetic medications including aprepitant, casopitant, fosaprepitant, netupitant, rolapitant, and others, play an efficient role in both acute and delayed CINV control by blocking the binding of substance P to the NK‐1R in the vomiting center of the central nervous system [5], [6]. Recently, a large‐scale network meta‐analysis has further confirmed that different NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens (NK‐1RAs + serotonin receptor antagonist [5‐HT3RA] + corticosteroids) shared equivalent effect on CINV control in all the phases. And in patients with HEC, various NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens had superior antiemetic effect compared with duplex control regimens (5‐HT3RA + corticosteroids) [7]. In current practice, cancer patients who receive chemotherapy with the high potential to induce CINV are recommended to receive a triple regimen prophylaxis of NK‐1RAs, 5‐HT3RA, and dexamethasone (DEX) before chemotherapy [8], [9]. Basically, the control of CINV is more impressive in the acute phase than in the delayed phase. Also, it is more successful at overcoming emesis than at preventing nausea, especially delayed nausea, when standard antiemetic regimens were used. Despite the use of an NK1‐RA‐based triple regimen for the prevention of CINV, nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy may still occur.

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of schizophrenia, mania, and bipolar disorder since 1996 [10, 11]. As a single‐agent antipsychotic medication, it has a broad spectrum of antagonizing multiple receptors for neurotransmitters including dopamine (D1–D4 brain receptors), serotonin (5‐HT2a, 5‐HT2c, 5‐HT3, and 5‐HT6 receptors), histamine (H1 receptors), catecholamines (α1 adrenergic receptors), and acetylcholine (muscarinic receptors) [12]. Olanzapine's activity at multiple receptors, especially at the D2, 5‐HT2c, and 5‐HT3 receptors, which appear to play an important part in the pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting, has prompted its application in the treatment of CINV [13], [14]. Recently, interest in olanzapine as an antiemetic for CINV has grown. Case reports have demonstrated its efficacy in the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and emesis [15], [16], [17]. Several clinical trials have also revealed that olanzapine‐based triple regimens (olanzapine + 5‐HT3RA + corticosteroids) improved nausea control in patients receiving moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy [16], [18], [19], [20]. However, there was limited evidence to tell the difference between the olanzapine‐based triple regimens and the different NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens. Therefore, it was necessary to perform a network meta‐analysis to carry out the comparison of these two antiemetic regimens. We sought to explore this comparison through integrating and indirect methods of network meta‐analysis in our current study, hoping this result can offer some useful information for oncologists regarding decision‐making for CINV.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

We systematically searched for eligible random control trials (RCTs) up to March 23, 2017, in the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases, WangFang Data, and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, with no restriction on language, status, or year of publication. We used a combination of the terms “olanzapine,” “neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist,” “NK‐1,” “aprepitant,” “casopitant,” “fosaprepitant,” “netupitant,” “rolapitant,” “chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting,” and “CINV” to find relevant articles and ensure the latest research progress was included. An additional search through conference abstracts, reference lists of selected trials, relevant previous systematic reviews, and meta‐analysis was also conducted. Three authors (ZY, ZZ, and CG) carried out the literature search independently.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible studies met the following criteria: (a) RCTs or prospective studies that compared olanzapine, NK‐1RAs‐based triple antiemetic regimens, and duplex regimens in the prophylaxis of CINV. (b) The participants were malignant tumor patients using HEC instead of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC; the emetogenic potential of chemotherapy was defined according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] Antiemesis Guideline Version 2, 2017) [9]. (c) Antiemetic efficacy ± toxicity measures were available. (d) Standardized antiemetic regimen was used. Studies failing to meet the above inclusion criteria were excluded.

Outcome Measures

The proportion of patients in overall (0–120 hours), acute (0–24 hours after chemotherapy) and delayed (>24–120 hours after chemotherapy) phases (OP, AP, and DP, respectively), complete responses (CRs), and no nausea were the antiemetic efficacy outcomes in this study. The toxicity outcome was drug‐related adverse event (DRAE). The assessment of efficacy and toxicity was during one cycle of chemotherapy.

Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Quality Assessment

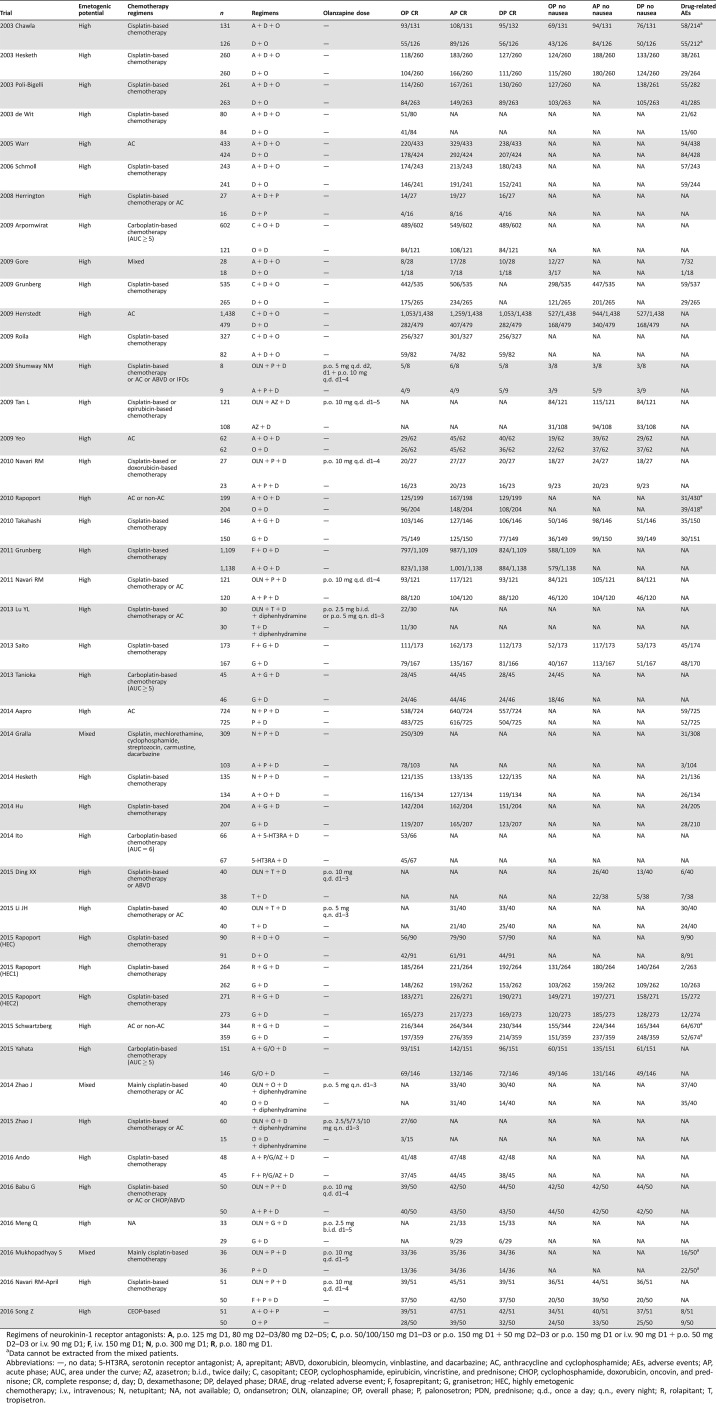

The titles, abstracts, and full texts of each study were examined independently by two investigators (ZZ and LF) to assess their eligibility. Disagreements were discussed with a third author (ZY) to reach a consensus. Jadad scale was used to assess the quality of all included studies [21]. All eligible studies were of high quality after the assessment. The same authors used a standardized form to extract data independently. With respect to several reports pertaining to the same trial, we gave priority to the data from published articles, conference abstracts, and results posted at ClinicalTrials.gov as the first available source. For trials or conference abstracts with incomplete results, we tried to contact study investigators and request the missing outcome data if available. For each enrolled study, we extracted data concerning the publication, trial and patient characteristics, description of the interventions, and outcome data (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies for network meta‐analyses.

Regimens of neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists: A, p.o. 125 mg D1, 80 mg D2–D3/80 mg D2–D5; C, p.o. 50/100/150 mg D1–D3 or p.o. 150 mg D1 + 50 mg D2–D3 or p.o. 150 mg D1 or i.v. 90 mg D1 + p.o. 50 mg D2–D3 or i.v. 90 mg D1; F, i.v. 150 mg D1; N, p.o. 300 mg D1; R, p.o. 180 mg D1.

Data cannot be extracted from the mixed patients.

Abbreviations: —, no data; 5‐HT3RA, serotonin receptor antagonist; A, aprepitant; ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; AC, anthracycline and cyclophosphamide; AEs, adverse events; AP, acute phase; AUC, area under the curve; AZ, azasetron; b.i.d., twice daily; C, casopitant; CEOP, cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone; CR, complete response; d, day; D, dexamethasone; DP, delayed phase; DRAE, drug ‐related adverse event; F, fosaprepitant; G, granisetron; HEC, highly emetogenic chemotherapy; i.v., intravenous; N, netupitant; NA, not available; O, ondansetron; OLN, olanzapine; OP, overall phase; P, palonosetron; PDN, prednisone; q.d., once a day; q.n., every night; R, rolapitant; T, tropisetron.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Another two investigators (HS and MY) assessed the risk of bias of the studies by using the risk of bias tool following the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines (http://www.cochrane.de). Disagreements were discussed with a third author (CG). The details of risk of bias for included studies can be found in supplemental online Figure 1A, 1B.

Statistical Analysis

First, we performed pair‐wise meta‐analyses with a random‐effect model to synthesize studies comparing olanzapine‐based triple regimens and NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens. The results were reported as pooled odds ratios (ORs) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). For CR and no nausea, an OR >1 means a better antiemetic efficacy in the former regimen. For DRAE, an OR >1 means a more drug‐related toxicity in the former regimen. Statistical heterogeneity across studies was assessed with a forest plot and the inconsistency statistic. A fixed‐effect model was employed when its p value >.1. Otherwise, the random‐effect model would be applied. Statistical significance was considered at p < .05. All calculations were performed using Review Manager (version 5.3 for Windows; the Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, U.K.). Subsequently, we set up a random‐effects network within a Bayesian framework using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods in ADDIS 1.16 (Drugis.org) [22], [23]. Binary clinical outcomes within studies were networked and the relations among the ORs across studies were specified to make comparisons of different antiemetic treatments in terms of efficacy and/or toxicity. Statistical significance was assessed using p values <.05 and 95% CIs. The inconsistency within this multiple treatment comparison was evaluated by a variance calculation such as inconsistency standard deviation (ISD) and inconsistency factors (IF). If the 95% CIs of ISD included “1” or the 95% CIs of IF contain “0,” that would indicate a low risk of inconsistency. A node‐splitting analysis by the software ADDIS 1.16 was also provided to test the consistency between direct evidence and indirect evidence for their agreement on a specific note [23]. The results of the inconsistency evaluation are shown in supplemental online Tables 1–8). This framework also allowed us to estimate the rank probability to show the best treatment among all these antiemetic regimens.

Results

Eligible Studies and Characteristics

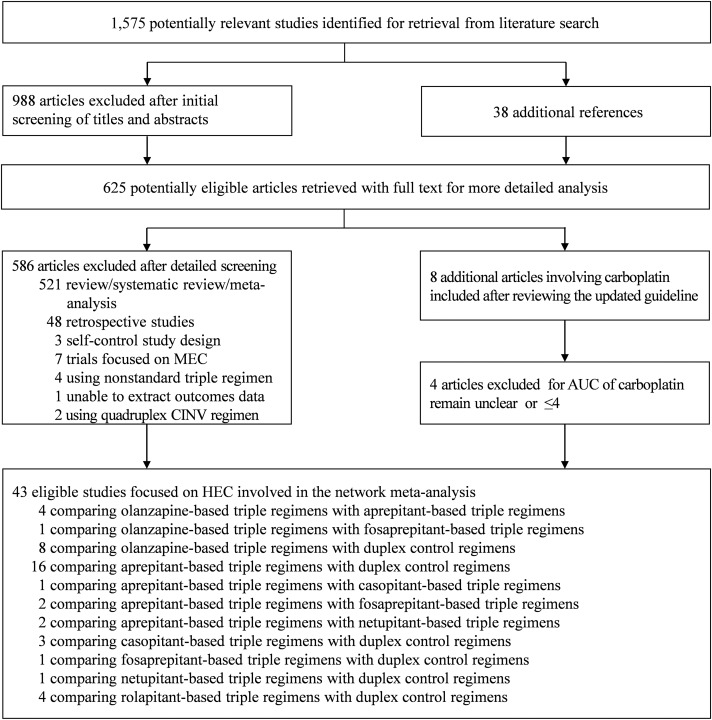

We identified 1,613 records about CINV through database searching and focused on 61 potentially relevant randomized control trials with olanzapine‐based triple regimens or NK‐1RAs‐base triple regimens in the experimental arm. However, 18 trials were not eligible for the following reasons: associating with MEC [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], using nonstandard triple CINV regimens [31], [32], [33], [34], unavailable measured outcomes [35], carboplatin area under the curve remain unclear [36], [37], [38], [39], and using quadruplex antiemetic regimens in the experimental arm [40], [41]. We finally included 42 trials [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83] focused on HEC involving 16,609 cancer patients using olanzapine‐based triple regimens (olanzapine + 5‐HT3RA + dexamethasone, n = 657), NK‐1Ras‐based triple regimens (NK‐1RAs + 5‐HT3RA + dexamethasone, n = 10,510), or conventional duplex control regimens (5‐HT3RA + dexamethasone, n = 5,442) to control CINV in this network meta‐analysis. Figure 1 summarizes the flow diagram of the study selection. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of all included studies, such as trial name, chemotherapy category, antiemetic regimens, the dose of olanzapine, and clinical outcomes.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection for the comparison of olanzapine‐based triple regimens and neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists‐based regimens in patients with HEC.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CINV, chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting; HEC, highly emetogenic chemotherapy; MEC, moderately emetogenic chemotherapy.

Pair‐Wise Meta‐Analyses for Antiemetic Efficacy and Toxicity

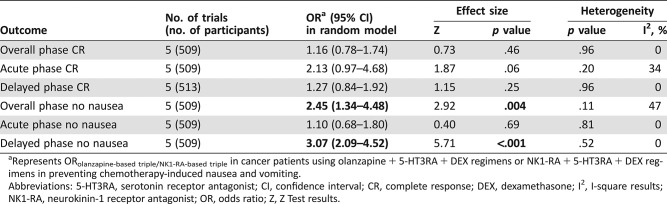

There were five head‐to‐head studies comparing the efficacy between olanzapine‐based triple regimens and NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens [55], [59], [60], [82], [83]. In our pair‐wise meta‐analyses, olanzapine‐based triple regimens showed superior antiemetic effect significantly in OP no nausea and DP no nausea when compared with NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens in overall patients treated with HEC. However, no significant differences in OP CR, AP CR, and DP CR, as well as AP no nausea, were found between these two regimens. The comparison of toxicity wasn't carried out due to the unavailable adverse events (AEs) data from these studies (Table 2; supplemental online Fig. 2). We conducted funnel plots to assess the publication bias of the literature in this study. All the shapes of the funnels were close to symmetry and no publication bias was found according to Begg's test and Egger's test (p > .05).

Table 2. Binary comparison of olanzapine + 5‐HT3RA + DEX regimens versus NK1‐RA + 5‐HT3RA + DEX regimens for antiemetic efficacy.

Represents ORolanzapine‐based triple/NK1‐RA‐based triple in cancer patients using olanzapine + 5‐HT3RA + DEX regimens or NK1‐RA + 5‐HT3RA + DEX regimens in preventing chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting.

Abbreviations: 5‐HT3RA, serotonin receptor antagonist; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; DEX, dexamethasone; I2, I‐square results; NK1‐RA, neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist; OR, odds ratio; Z, Z Test results.

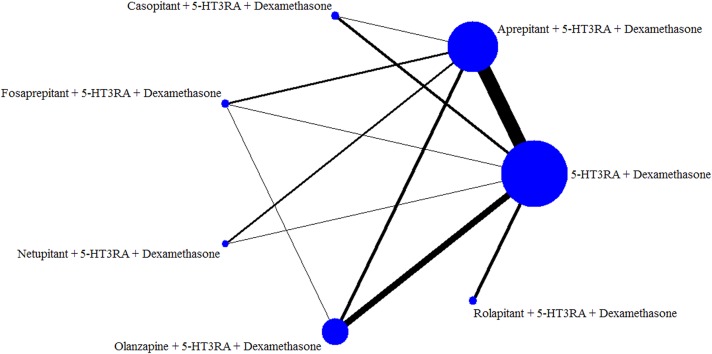

Networks for Multiple Treatment Comparisons

The network was designed for multiple treatment comparisons (MTCs) of olanzapine‐based triple antiemetic regimens (olanzapine + 5HT3RA + dexamethasone) and different NK‐1RAs‐based triple antiemetic regimens (NK‐1RAs + 5HT3RA + dexamethasone) and duplex control regimens (5‐HT3RA + dexamethasone; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Network established for multiple treatment comparisons of olanzapine‐based triple regimens and different neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonists‐based triple regimens for patients with highly emetogenic chemotherapy.

Abbreviation: 5‐HT3RA, serotonin receptor antagonist.

Network Meta‐Analyses for Antiemetic Efficacy and Toxicity

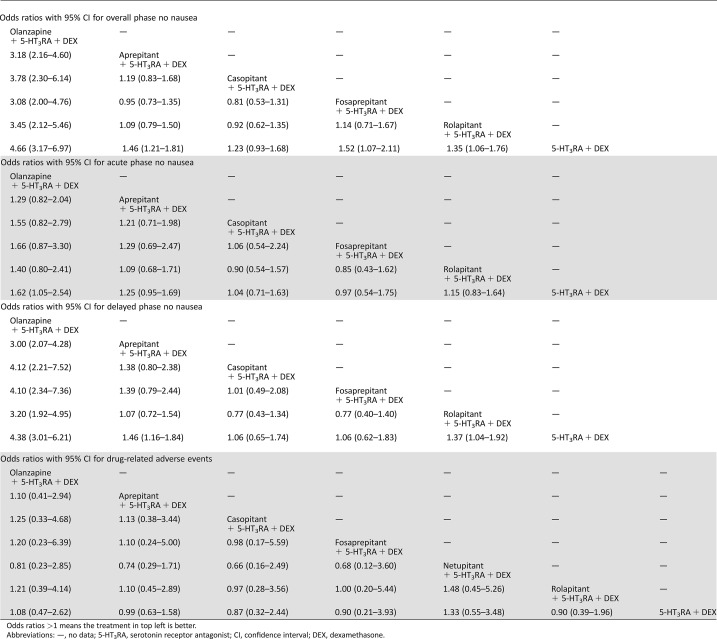

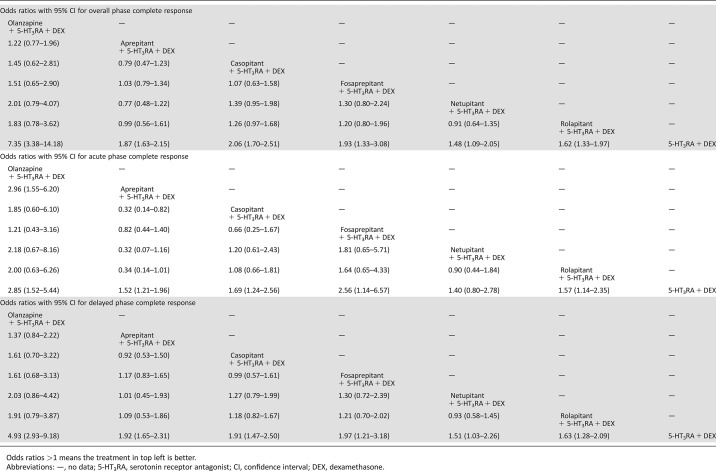

According to the established network (Fig. 2), based on the consistency model, olanzapine‐based triple regimens showed significantly higher OP and DP no nausea than NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens, whereas only AP no‐nausea olanzapine‐based triple regimens showed no significant antiemetic effect with different NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens (Table 3). No significant differences in DRAE among olanzapine‐based triple regimens, NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens, and duplex control regimens were found in this study (Table 3). On the other hand, based on the inconsistency model, olanzapine‐based triple regimens shared equivalent antiemetic effect in OP, AP, and DP CRs without significant differences in ORs when compared with various NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens (aprepitant, casopitant, fosaprepitant, netupitant, and rolapitant) in patients with HEC, of which olanzapine‐based triple regimens showed better efficacy in AP CR than aprepitant‐based triple regimens (OR, [95% CI], 2.96 [1.55, 6.20]). However, in this model, olanzapine‐based triple regimens and almost all NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens were significantly superior to duplex control regimens in OP, AP, and DP CRs, whereas only netupitant‐based triple regimens showed a nonsignificant superior antiemetic efficacy compared with duplex control regimens in terms of AP CR (Table 4), which has been demonstrated in our former study [7].

Table 3. Multiple treatment comparison for no nausea and drug‐related adverse events based on network consistency model.

Odds ratios >1 means the treatment in top left is better.

Abbreviations: —, no data; 5‐HT3RA, serotonin receptor antagonist; CI, confidence interval; DEX, dexamethasone.

Table 4. Multiple treatment comparison for complete response based on network inconsistency model.

Odds ratios >1 means the treatment in top left is better.

Abbreviations: —, no data; 5‐HT3RA, serotonin receptor antagonist; CI, confidence interval; DEX, dexamethasone.

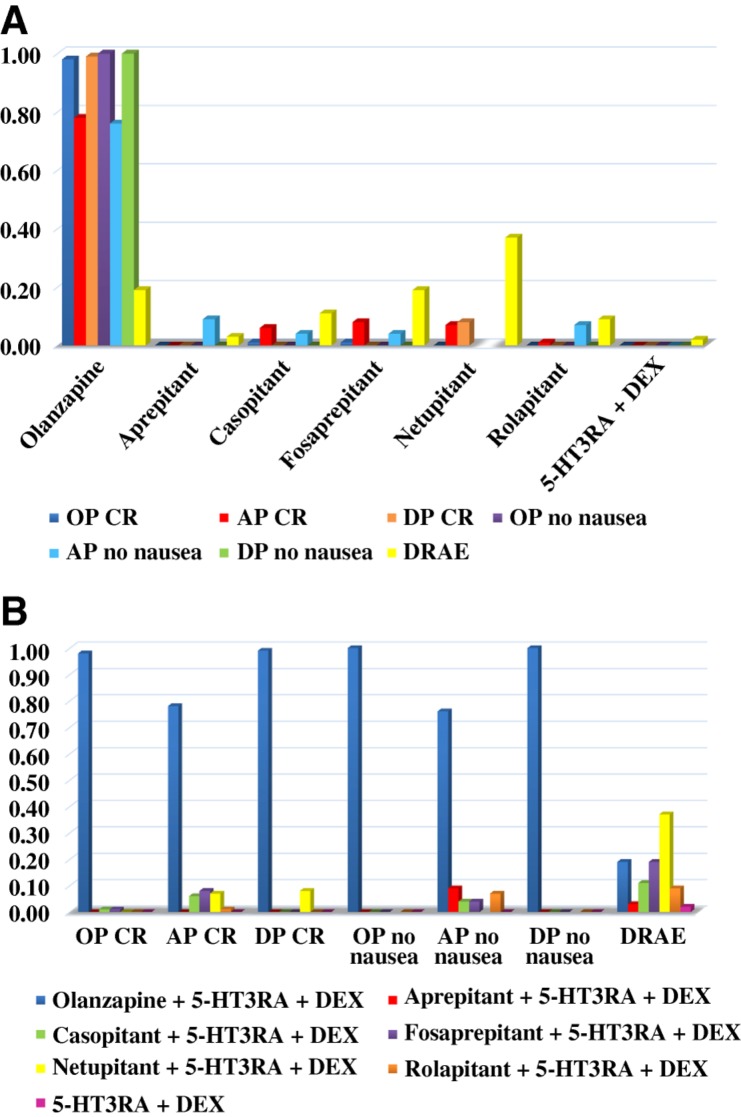

The “rank probabilities” produced by the network consistency model tend to indicate the probabilities of which antiemetic regimen can rank best in all outcomes measured (OP, AP, and DP no nausea, etc.), but the rank probabilities of various antiemetic regimens do not intend to be statistically significant among each other in all these outcomes. Regimens with greater value in the histogram were associated with greater probabilities for better outcomes. The probability to rank in the first place among all these antiemetic regimens was extracted and shown in Figure 3. According to the ranking, it's notable that olanzapine‐based triple regimens ranked best among all the regimens in all the outcomes measured. Figure 3A was classified by regimens and Figure 3B by outcomes. Distribution of probabilities of each regimen being ranked at each of the possible positions was displayed in line chart (supplemental online Fig. 3A–3G).

Figure 3.

Distribution of probabilities of each chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting regimen being ranked first place based on network, classified by regimens (A) and by outcomes (B).

Abbreviations: 5‐HT3RA, serotonin receptor antagonist; AP, acute phase; CR, complete response; DEX, dexamethasone; DP, delayed phase; DRAE, drug‐related adverse event; OP, overall phase.

Drug Unit Cost and Sources

Data on unit costs and drug dosage and administration were listed in detail in supplemental online Table 9. Drug costs were extracted from the online RxUSA Pharmacy (http://rxusa.com) and were expressed in U.S. dollars. Dosage and administration of various drugs were represented according to the trials we included. In accordance with the dosage and administration setting, the unit costs of olanzapine (ranged from $39 to $119) were much lower than aprepitant (ranged from $256 to $328), fosaprepitant ($345), netupitant ($768), and rolapitant ($662). The unit costs of casopitant are unknown because the drug has not been available on the market and there is little information about its marketing price.

Discussion

Recent binary meta‐analysis studies have demonstrated that olanzapine is efficacious and safe when used as a prophylaxis for CINV [84], [85], [86]; however, these studies didn't compare the efficacy and toxic profile between olanzapine‐based triple regimens and other NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens due to the limitation of the methodology itself. To our knowledge, our current study is the first network meta‐analysis to compare the antiemetic efficacy and toxicity among olanzapine‐based triple regimens and various NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens. A previous study proved that different kinds of NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens shared equivalent effect on CINV control in all the phases and NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens had superior antiemetic effect compared with duplex control regimens in patients with HEC [7]. In accordance with the pair‐wise analysis results, our multiple treatment comparisons showed that antiemetic effect of olanzapine‐based triple regimens was similar to NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens in terms of OP, AP, and DP CRs after chemotherapy in patients with HEC. Concerning nausea control, however, olanzapine‐based triple regimens exhibited an impressive improvement in the OP and especially the DP no nausea, which often upsets patients and leads to a decrease in quality of life. As expected, either the olanzapine‐based or NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens demonstrated a significantly higher antiemetic efficacy than conventional duplex regimens in patients with HEC.

Consistent with the results of individual RCTs, our study confirmed that olanzapine‐based triple regimens had higher efficacy of CINV control than duplex control regimens in patients receiving HEC. We also found that olanzapine‐based triple regimens showed similar effect on CINV control in contrast with various NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens in phases of CRs. And in nausea control, olanzapine‐based triple regimens appeared to be superior in both overall and delayed phase when compared with other NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens. Thus, olanzapine‐based triple regimens, in parallel with NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens, could be another choice for patients receiving HEC. Heretofore, NCCN guidelines have recommended a combination of olanzapine, palonosetron, and dexamethasone antiemetic regimen for patients receiving HEC [9]. Our study, via a large‐scale meta‐analysis, further confirmed that patients receiving HEC could derive significant benefit from applying olanzapine‐based triple regimens. Our findings might suggest the application of olanzapine‐based triple regimens for patients receiving HEC, especially those experiencing difficulty overcoming delayed CINV. The possible mechanistic rationale for olanzapine's efficacy in both the prevention and rescue of CINV may lie in the binding affinity of olanzapine to multiple neurotransmitter receptors including D2, 5‐HT2c, and 5‐HT3 receptors [13].

In the evaluation of inconsistency, we found that inconsistency standard deviation (ISD) and inconsistency factors (IF) indicated a low risk of inconsistency of this study (supplemental online Table 1). However, in the node‐splitting analysis testing the consistency between direct evidence and indirect evidence, we found that not all the results lived up to the consistency with respect to OP, AP, and DP CRs (supplemental online Tables 2–8). The reasons for possible inconsistency may include the following: Firstly, limited studies and patients involving olanzapine‐based regimens were synthesized in comparison with the NK‐1RAs‐based regimens and duplex regimens. Secondly, the administration and dosage of olanzapine, ranging from 2.5 mg daily to 10 mg daily in the whole experimental period, was not standardized or unified because of the lack of guideline‐directed olanzapine‐based antiemetic combinations when these relevant trials were taking place. Because we use the network meta‐analysis (NMA) to compare multiple interventions, the inconsistency may be added up in the process of synthesizing direct and indirect evidence from RCTs [22], [23]. To cope with this, our study built up the consistency model for no nausea and DRAE, as well as the inconsistency model for CRs, to better describe the efficacy and toxicity relationship and to comprehensively interrupt the results of different antiemetic regimens, which makes it closer to the real‐world situation. When including the qualified studies, two investigators (HS and MY) of our team conducted the assessment independently to guarantee the quality of the literature. In this process, a recent study comparing olanzapine‐based quadruplet regimens (olanzapine + NK‐1RAs + 5‐HT3RA + DEX) with the NK‐1RAs‐based triplet regimens (placebo + NK‐1RAs + 5‐HT3RA + DEX) was excluded [41]. On one hand, this quadruplet‐versus‐triplet study may increase the inconsistency in the current established network if it was included. On the other hand, the no‐nausea rate in all phases in the control group from this study was much lower than the previous reported study [44], [45], [51], [52], which would inevitably cause data inconsistency in our study.

As for cost‐effectiveness, the costs data (supplemental online Table 9) revealed that the costs of the olanzapine‐based regimen were obviously much lower than the NK‐1RA‐based regimen in therapeutic dose range and administration setting for the treatment of CINV. From this perspective, olanzapine, which shared equivalent efficacy but cost less, is an excellent alternative for prophylaxis of CINV for cancer patients with HEC.

There were several limitations in the present study. Firstly, some outcome data, especially for DRAE, were unavailable from some included studies. And in some included studies that enrolled mixed patients,the specific DRAE data with HEC were unable to extract. Meanwhile, because the toxicity spectrum distinctly differed from olanzapine and NK‐1RAs, some specific adverse events, like sedation and dizziness, were unable to be compared separately. Hence, we could only extract data of DRAE that provided a general impression of olanzapine‐based and NK‐1RAs‐based regimens in the aspect of safety and tolerability profile. Because of the lack of individual patient data, some further analysis of specific tolerability profile couldn't be performed to date. Secondly, the limited sample size of olanzapine‐based regimens may result in inconsistency to some extent. The current available olanzapine studies included 13 trials, involving 657 patients in olanzapine‐based triple regimens, which were much smaller in comparison with the sample size of NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens. However, it was up to now the relatively full‐fledged clinical data that were available for analysis and synthesis. Thirdly, we could not compare olanzapine‐based antiemetic regimens directly with netupitant‐based, casopitant‐based, and rolapitant‐based triple regimen because of the lack of relative studies. Fourthly, we compromised to take the “no nausea” as an appropriate outcome endpoint in these studies, which was more attainable and extractable in contrast with other endpoints such as “no significant nausea” for this present study. The blinding implementation of these studies was not quite satisfactory; the schedule and dose of olanzapine was unstandardized because of the lack of guideline‐directed olanzapine‐based antiemetic regimens when these trials were conducted. Despite the blind method, these studies basically lived up to the RCTs standards and were persuasive in terms of prospective and demonstrable intensity to a certain extent. Formal clinical trials and future studies were warranted to further testify our results by replenishing the current unavailable data.

Nonetheless, regardless of the above limitations, our study contributed comprehensive evidence to oncologists in the treatment of CINV associated with HEC. Our findings confirmed that olanzapine‐based triple regimens possessed a superior control of nausea, especially in the overall and delayed phases, in patients with HEC. And it also revealed that olanzapine‐based triple regimens shared equivalent effect on CINV control with different NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens in terms of CRs. As for safety profile, the drug‐related adverse events indicated there were no significant differences among olanzapine‐based, NK‐1RAs‐based, and duplex control regimens. For patients with HEC and those suffering from delayed nausea, the antiemetic prophylaxis combination of olanzapine, 5‐HT3RA, and corticosteroids might be a priority. More evidence is required for future updates.

Conclusion

Olanzapine‐based triple regimens stood out in the overall and delayed phases of nausea control but shared equivalent effect in terms of CRs toward different NK‐1RAs‐based triple regimens for patients with HEC on CINV control. For patients with HEC, especially those suffering from delayed nausea, the antiemetic prophylaxis combination of olanzapine, 5‐HT3RA, and corticosteroids should be an optional antiemetic choice.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

No drug manufacturing company was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the report for publication. All authors saw and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant number 2016YFC0905500) and The 5010 Clinical Research Foundation of Sun Yat‐sen University (Grant number 2016001).

Contributed equally

Contributor Information

Hongyun Zhao, Email: zhaohy@sysucc.org.cn.

Li Zhang, Email: zhangli6@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Yaxiong Zhang, Hongyun Zhao, Li Zhang

Collection and/or assembly of data: Zhonghan Zhang, Yaxiong Zhang, Gang Chen, Shaodong Hong, Yunpeng Yang, Wenfeng Fang, Fan Luo, Xi Chen, Yuxiang Ma, Yuanyuan Zhao, Jianhua Zhan

Data analysis and interpretation: Zhonghan Zhang, Yaxiong Zhang, Gang Chen, Shaodong Hong, Yunpeng Yang, Wenfeng Fang, Fan Luo, Xi Chen, Yuxiang Ma, Yuanyuan Zhao, Jianhua Zhan, Cong Xue, Xue Hou, Ting Zhou, Shuxiang Ma, Fangfang Gao, Yan Huang, Likun Chen, Ningning Zhou, Hongyun Zhao, Li Zhang

Manuscript writing: Zhonghan Zhang, Yaxiong Zhang, Gang Chen, Hongyun Zhao, Li Zhang

Final approval of manuscript: Zhonghan Zhang, Yaxiong Zhang, Gang Chen, Shaodong Hong, Yunpeng Yang, Wenfeng Fang, Fan Luo, Xi Chen, Yuxiang Ma, Yuanyuan Zhao, Jianhua Zhan, Cong Xue, Xue Hou, Ting Zhou, Shuxiang Ma, Fangfang Gao, Yan Huang, Likun Chen, Ningning Zhou, Hongyun Zhao, Li Zhang

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Laszlo J. Nausea and vomiting as major complications of cancer chemotherapy. Drugs 1983;25(suppl 1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osoba D, Zee B, Pater J et al. Determinants of postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer. Quality of Life and Symptom Control Committees of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ballatori E, Roila F. Impact of nausea and vomiting on quality of life in cancer patients during chemotherapy. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Navari RM. Management of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: Focus on newer agents and new uses for older agents. Drugs 2013;73:249–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watanabe Y, Asai H, Ishii T et al. Pharmacological characterization of T‐2328, 2‐fluoro‐4'‐methoxy‐3'‐[[[(2S,3S)‐2‐phenyl‐3‐piperidinyl]amino]methyl]‐[1,1'‐biphenyl]‐4‐carbonitrile dihydrochloride, as a brain‐penetrating antagonist of tachykinin NK1 receptor. J Pharmacol Sci 2008;106:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rojas C, Slusher BS. Pharmacological mechanisms of 5‐HT 3 and tachykinin NK 1 receptor antagonism to prevent chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol 2012;684:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang Y, Yang Y, Zhang Z et al. Neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist‐based triple regimens in preventing chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: A network meta‐analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;109:pii: djw217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Molassiotis A, Aapro M, Herrstedt J et al. MASCC/ESMO Antiemetic Guidelines: Introduction to the 2016 guideline update. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:267–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berger MJ, Ettinger DS, Aston J et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Antiemesis, Version 2.2017. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2017;15:883–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kando JC, Shepski JC, Satterlee W et al. Olanzapine: A new antipsychotic agent with efficacy in the management of schizophrenia. Ann Pharmacother 1997;31:1325–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olanzapine Prescribing Information. Eli Lilly and Company. 2009. Available at: http://pi.lilly.com/us/zyprexa-pi.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2009.

- 12. Bymaster FP, Calligaro DO, Falcone JF et al. Radioreceptor binding profile of the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996;14:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bymaster FP, Falcone JF, Bauzon D et al. Potent antagonism of 5‐HT(3) and 5‐HT(6) receptors by olanzapine. Eur J Pharmacol 2001;430:341–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Navari RM. Olanzapine for the prevention and treatment of chronic nausea and chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;722:180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pirl WF, Roth AJ. Remission of chemotherapy‐induced emesis with concurrent olanzapine treatment: A case report. Psychooncology 2000;9:84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Passik SD, Lundberg J, Kirsh KL et al. A pilot exploration of the antiemetic activity of olanzapine for the relief of nausea in patients with advanced cancer and pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;23:526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson WC, Tavernier L. Olanzapine for intractable nausea in palliative care patients. J Palliat Med 2003;6:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Navari RM, Einhorn LH, Passik SD et al. A phase II trial of olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: A Hoosier Oncology Group study. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Navari RM, Einhorn LH, Loehrer PS et al. A phase II trial of olanzapine, dexamethasone, and palonosetron for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: A Hoosier oncology group study. Support Care Cancer 2007;15:1285–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Passik SD, Navari RM, Jung SH et al. A phase I trial of olanzapine (Zyprexa) for the prevention of delayed emesis in cancer patients: A Hoosier Oncology Group study. Cancer Invest 2004;22:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Jadad AR, Nichol G et al. Assessing the quality of randomized controlled trials: An annotated bibliography of scales and checklists. Control Clin Trials 1995;16:62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salanti G, Higgins JP, Ades AE et al. Evaluation of networks of randomized trials. Stat Methods Med Res 2008;17:279–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van Valkenhoef G, Tervonen T, Zwinkels T et al. ADDIS: A decision support system for evidence‐based medicine. Decis Support Syst 2013;55:459–475. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hesketh PJ, Wright O, Rosati G et al. Single‐dose intravenous casopitant in combination with ondansetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of oxaliplatin‐induced nausea and vomiting: A multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, active‐controlled, two arm, parallel group study. Support Care Cancer 2012;20:1471–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schmitt T, Goldschmidt H, Neben K et al. Aprepitant, granisetron, and dexamethasone for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting after high‐dose melphalan in autologous transplantation for multiple myeloma: Results of a randomized, placebo‐controlled phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kitayama H, Tsuji Y, Sugiyama J et al. Efficacy of palonosetron and 1‐day dexamethasone in moderately emetogenic chemotherapy compared with fosaprepitant, granisetron, and dexamethasone: A prospective randomized crossover study. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20:1051–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nishimura J, Satoh T, Fukunaga M et al. Combination antiemetic therapy with aprepitant/fosaprepitant in patients with colorectal cancer receiving oxaliplatin‐based chemotherapy (SENRI trial): A multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:1274–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Micha JP, Rettenmaier MA, Brown JV 3rd et al. A randomized controlled pilot study comparing the impact of aprepitant and fosaprepitant on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in patients treated for gynecologic cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2015;26:389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aridome K, Mori SI, Baba K et al. A phase II, randomized study of aprepitant in the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic chemotherapies in colorectal cancer patients. Mol Clin Oncol 2016;4:393–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weinstein C, Jordan K, Green SA et al. Single‐dose fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: Results of a randomized, double‐blind phase III trial. Ann Oncology 2016;27:172–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. LH W. Effectiveness of olanzapine combined with tropisetron in prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting of small cell lung cancer. Henan J Surg 2013. Available at: http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/hnwkxzz201306007. Accessed January 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32. JF G. Antiemetic effect of low dose olanzapine in solid tumor chemotherapy. J Clin Med Lit (Electronic Edition) 2014;954 Available at: http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-LCWX201406055.htm. Accessed January 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. GZ L. The observation of the effects of olanzapine combined with granisetron in preventing nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy of breast cancer. Oncol Progress 2014. Available at: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-AZJZ201406015.htm. Accessed January 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang X, Wang L, Wang H et al. Effectiveness of olanzapine combined with ondansetron in prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting of non‐small cell lung cancer. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015;72:471–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhong Sheng G, Hao W, Wen Tong F et al. Observation of olanzapine joint tropisetron and dexamethasone in prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by cisplatin. Pharm Clin Res 2015;309–312. Available at: http://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/Periodical/jsyxylcyj201503029. Accessed January 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maehara M, Ueda T, Miyahara D et al. Clinical efficacy of aprepitant in patients with gynecological cancer after chemotherapy using paclitaxel and carboplatin. 2015;35:4527–4534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hesketh PJ, Schnadig ID, Schwartzberg LS et al. Efficacy of the neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist rolapitant in preventing nausea and vomiting in patients receiving carboplatin‐based chemotherapy. Cancer 2016;122:2418–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jordan K, Gralla R, Rizzi G et al. Efficacy benefit of an NK1 receptor antagonist (NK1RA) in patients receiving carboplatin: Supportive evidence with NEPA (a fixed combination of the NK1 RA, netupitant, and palonosetron) and aprepitant regimens. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:4617–4625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim JE, Jang JS, Kim JW et al. Efficacy and safety of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting during the first cycle of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy in Korean patients with a broad range of tumor types. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mizukami N, Yamauchi M, Koike K et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Pain Symptom Manageme 2014;47:542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med 2016;375:134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. de Wit R, Herrstedt J, Rapoport B et al. Addition of the oral NK1 antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetics provides protection against nausea and vomiting during multiple cycles of cisplatin‐based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4105–4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Poli‐Bigelli S, Rodrigues‐Pereira J, Carides AD et al. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer 2003;97:3090–3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chawla SP, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ et al. Establishing the dose of the oral NK1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer 2003;97:2290–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hesketh PJ, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ et al. The oral neurokinin‐1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: A multinational, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial in patients receiving high‐dose cisplatin–the Aprepitant Protocol 052 Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4112–4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Warr DG, Hesketh PJ, Gralla RJ et al. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2822–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schmoll HJ, Aapro MS, Poli‐Bigelli S et al. Comparison of an aprepitant regimen with a multiple‐day ondansetron regimen, both with dexamethasone, for antiemetic efficacy in high‐dose cisplatin treatment. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1000–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Herrington JD, Jaskiewicz AD, Song J. Randomized, placebo‐controlled, pilot study evaluating aprepitant single dose plus palonosetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of acute and delayed chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer 2008;112:2080–2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Roila F, Rolski J, Ramlau R et al. Randomized, double‐blind, dose‐ranging trial of the oral neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist casopitant mesylate for the prevention of cisplatin‐induced nausea and vomiting. Ann Oncol 2009;20:1867–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arpornwirat W, Albert I, Hansen VL et al. Phase 2 trial results with the novel neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist casopitant in combination with ondansetron and dexamethasone for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Cancer 2009;115:5807–5816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gore L, Chawla S, Petrilli A et al. Aprepitant in adolescent patients for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of efficacy and tolerability. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;52:242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yeo W, Mo FK, Suen JJ et al. A randomized study of aprepitant, ondansetron and dexamethasone for chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting in Chinese breast cancer patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;113:529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Grunberg SM, Rolski J, Strausz J et al. Efficacy and safety of casopitant mesylate, a neurokinin 1 (NK1)‐receptor antagonist, in prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving cisplatin‐based highly emetogenic chemotherapy: A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Herrstedt J, Apornwirat W, Shaharyar A et al. Phase III trial of casopitant, a novel neurokinin‐1 receptor antagonist, for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:5363–5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shumway NM, Terrazzino SE, Jones CB. A randomized pilot study comparing aprepitant to olanzapine for treatment of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(suppl 15):9633. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tan L, Liu J, Liu X et al. Clinical research of Olanzapine for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2009;28:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rapoport BL, Jordan K, Boice JA et al. Aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting associated with a broad range of moderately emetogenic chemotherapies and tumor types: A randomized, double‐blind study. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Takahashi T, Hoshi E, Takagi M et al. Multicenter, phase II, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomized study of aprepitant in Japanese patients receiving high‐dose cisplatin. Cancer Sci 2010;101:2455–2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): A randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(suppl 15):9020a Available at: http://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/jco.2010.28.15_suppl.9020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: A randomized phase III trial. J Support Oncol 2011;9:188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lü YL, Liu W, YJ Du et al. Antiemetic effect of low dose olanzapine in solid tumor chemotherapy. Chinese J Cancer Prev Treat 2013;20:544–554. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tanioka M, Kitao A, Matsumoto K et al. A randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study of aprepitant in nondrinking women younger than 70 years receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2013;109:859–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Saito H, Yoshizawa H, Yoshimori K et al. Efficacy and safety of single‐dose fosaprepitant in the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving high‐dose cisplatin: A multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Ann Oncol 2013;24:1067–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hu Z, Cheng Y, Zhang H et al. Aprepitant triple therapy for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting following high‐dose cisplatin in Chinese patients: A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase III trial. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gralla RJ, Bosnjak SM, Hontsa A et al. A phase III study evaluating the safety and efficacy of NEPA, a fixed‐dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting over repeated cycles of chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2014;25:1333–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hesketh PJ, Rossi G, Rizzi G et al. Efficacy and safety of NEPA, an oral combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy: A randomized dose‐ranging pivotal study. Ann Oncol 2014;25:1340–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ito Y, Karayama M, Inui N et al. Aprepitant in patients with advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer receiving carboplatin‐based chemotherapy. Lung Cancer 2014;84:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Aapro M, Rugo H, Rossi G et al. A randomized phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of NEPA, a fixed‐dose combination of netupitant and palonosetron, for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2014;25:1328–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhao J, Li X, Gao J et al. Clinical observation of olanzapine for prevention of high and moderate emetic risk chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. J Mod Oncol 2014;8:1941–1943. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rapoport BL, Schwartzberg LS, Chasen MR et al. Efficacy and safety of rolapitant for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) over multiple cycles of highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC, MEC). J Clin Oncol 2015;33(suppl 29):210a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rapoport B, Chua D, Poma A et al. Study of rolapitant, a novel, long‐acting, NK‐1 receptor antagonist, for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) due to highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC). Support Care Cancer 2015;23:3281–3288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rapoport BL, Chasen MR, Gridelli C et al. Safety and efficacy of rolapitant for prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting after administration of cisplatin‐based highly emetogenic chemotherapy in patients with cancer: Two randomised, active‐controlled, double‐blind, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Xiaoxiao D, Xinhua D. Efficacy of olanzapine combined with tropisetron, dexamethasone for the prevention of highly emetogenic chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. J Med Res 2015;44:143–146. Available at: http://www.yxyjzz.cn/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=20150540&flag=1 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Li J, Wei F, Zhang M et al. The clinical observation of small dose of olanzapine to prevent and control nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy. J Mod Oncol 2015;18:2673–2675. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhao J, Li X, Gao J et al. Curative effect and side effects of Olanzapine in treatment on nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy. J Mod Oncol 2015;2:275–277. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Meng Q, Chen GH, Guo PM. Olanzapine combined with normal antiemetic drugs in patients on solid tumor chemotherapy: Antiemetic effect and impact on quality of life. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2016;24:1117–1123. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ando Y, Hayashi T, Ito K et al. Comparison between 5‐day aprepitant and single‐dose fosaprepitant meglumine for preventing nausea and vomiting induced by cisplatin‐based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:871–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Grunberg S, Chua D, Maru A et al. Single‐dose fosaprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting associated with cisplatin therapy: Randomized, double‐blind study protocol–EASE. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1495–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yahata H, Kobayashi H, Sonoda K et al. Efficacy of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting with a moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimen: A multicenter, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind, randomized study in patients with gynecologic cancer receiving paclitaxel and carboplatin. Int J Clin Oncol 2016;21:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Song Z, Wang H, Zhang H et al. Efficacy and safety of triple therapy with aprepitant, ondansetron, and prednisone for preventing nausea and vomiting induced by R‐CEOP or CEOP chemotherapy regimen for non‐Hodgkin lymphoma: A phase 2 open‐label, randomized comparative trial. Leuk Lymphoma 2017;58:816–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Babu G, Saldanha SC, Chinnagiriyappa LK et al. The efficacy, safety, and cost benefit of olanzapine versus aprepitant in highly emetogenic chemotherapy: A pilot study from South India. Chemother Res Pract 2016;2016:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Navari RM, Nagy CK, Le‐Rademacher J et al. Olanzapine versus fosaprepitant for the prevention of concurrent chemotherapy radiotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. J Community Support Oncol 2016;14:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mukhopadhyay S, Kwatra G, Alice KP et al. Role of olanzapine in chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting on platinum‐based chemotherapy patients: A randomized controlled study. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wang XF, Feng Y, Chen Y et al. A meta‐analysis of olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting. Sci Rep 2014;4:4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Chiu L, Chow R, Popovic M et al. Efficacy of olanzapine for the prophylaxis and rescue of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting (CINV): A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:2381–2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yang T, Liu Q, Lu M et al. Efficacy of olanzapine for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting: A meta‐analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017;83:1369–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.