This paper is the first to describe the crystal structure of manganese superoxide dismutase from the genus Staphylococcus. Staphylococcus equorum and Bacillus subtilis MnSODs display different thermal and chemical stabilities. The slightly different structure of S. equorum MnSOD may provide an explanation for the differences in stability.

Keywords: manganese superoxide dismutase, Staphylococcus equorum MnSOD, structural comparison, thermostable enzymes

Abstract

A recombinant Staphylococcus equorum manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) with an Asp13Arg substitution displays activity over a wide range of pH, at high temperature and in the presence of chaotropic agents, and retains 50% of its activity after irradiation with UVC for up to 45 min. Interestingly, Bacillus subtilis MnSOD does not have the same stability, despite having a closely similar primary structure and thus presumably also tertiary structure. Here, the crystal structure of S. equorum MnSOD at 1.4 Å resolution is reported that may explain these differences. The crystal belonged to space group P3221, with unit-cell parameters a = 57.36, b = 57.36, c = 105.76 Å, and contained one molecule in the asymmetric unit. The symmetry operation indicates that the enzyme has a dimeric structure, as found in nature and in B. subtilis MnSOD. As expected, their overall structures are nearly identical. However, the loop connecting the helical and α/β domains of S. equorum MnSOD is shorter than that in B. subtilis MnSOD, and adopts a conformation that allows more direct water-mediated hydrogen-bond interactions between the amino-acid side chains of the first and last α-helices in the latter domain. Furthermore, S. equorum MnSOD has a slightly larger buried area compared with the dimer surface area than that in B. subtilis MnSOD, while the residues that form the interaction in the dimer-interface region are highly conserved. Thus, the stability of S. equorum MnSOD may not originate from the dimeric form alone. Furthermore, an additional water molecule was found in the active site. This allows an alternative geometry for the coordination of the Mn atom in the active site of the apo form. This is the first structure of MnSOD from the genus Staphylococcus and may provide a template for the structural study of other MnSODs from this genus.

1. Introduction

Superoxide dismutase (SOD; EC 1.15.1.1) splits superoxide (SO) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and oxygen (O2). The enzyme is the first line of defence against SO species in cells (Miller, 2012 ▸). The presence of SO species leads to oxidative stress in cells, to various diseases such as cancer and diabetes, and to cell death and ageing (Maritim et al., 2003 ▸). SOD protects the cell from ultraviolet (UV) radiation, thereby lowering the risk of cell damage (Acton, 2013 ▸). Therefore, SOD has been used in therapeutic applications and in cosmetics (Maritim et al., 2003 ▸; Lods et al., 2000 ▸).

SODs are grouped into four classes based on the metal ions in the active site, which can either be a copper–zinc pair (Cu/ZnSOD, also called SodC), nickel (NiSOD, SodN), iron (FeSOD, SodA) or manganese (MnSOD, SodB) (Abreu & Cabelli, 2010 ▸). MnSOD has a nearly identical structural architecture to FeSOD, although it has a different reaction mechanism. The metal at the active site can even be exchanged (cambialistic SODs; Abreu & Cabelli, 2010 ▸).

In initial work on S. equorum MnSOD only a partial nucleic acid sequence was elucidated; the full nucleotide sequence of the enzyme was reconstructed by insertion of the N- and C-termini of the gene encoding S. saprophyticus MnSOD (Retnoningrum et al., 2016 ▸). Therefore, the enzyme has previously been referred to as a hybrid of the MnSODs from S. equorum and S. saprophyticus (Retnoningrum et al., 2016 ▸). Subsequently, the amino-acid sequence was found to be almost identical to the more recently reported MnSOD sequence from S. equorum (GenBank WP_046465435.1) with the only substitution being at Asp13Arg. This substitution occurs in the part of the sequence of the hybrid enzyme from S. saprophyticus MnSOD. Nevertheless, this enzyme with the Asp13Arg substitution is designated S. equorum MnSOD. S. equorum MnSOD has amino-acid sequence similarity to other bacterial MnSODs, i.e. those from Bacillus subtilis (78.1%; PDB entry 2rcv; Liu et al., 2007 ▸), Deinococcus radiodurans (54.5%; PDB entry 2ce4; Dennis et al., 2006 ▸) and Escherichia coli (52.2%; PDB entry 1vew; Edwards et al., 1998 ▸). Owing to their high similarity in amino-acid sequence, the structure of B. subtilis MnSOD has been employed to study the structure and function of S. equorum MnSOD. However, these homologous enzymes have significantly different characteristics. For example, S. equorum MnSOD is still active at 353 K (Retnoningrum et al., 2016 ▸), at which temperature B. subtilis MnSOD is completely inactivated (Wang et al., 2014 ▸). S. equorum MnSOD is also more resistant to inactivation by urea or guanidinium chloride (chaotropic agents), by sodium dodecyl sulfate (a detergent) or by β-mercaptoethanol (a reducing agent) than B. subtilis MnSOD (Retnoningrum et al., 2016 ▸). These findings suggest that the B. subtilis MnSOD structure may be not representative of S. equorum MnSOD. Therefore, elucidation of the S. equorum MnSOD structure is of paramount importance.

Here, we report the crystal structure of S. equorum MnSOD, which is the first structure of an MnSOD from the genus Staphylococcus to be described. We discovered that the surface loop connecting the helical and α/β domains of the S. equorum MnSOD monomer is shorter and oriented inwards into the molecule, which might be a reason for the superior stability of S. equorum MnSOD over B. subtilis MnSOD. In addition, the active site of S. equorum MnSOD contains an additional water molecule that is not observed in B. subtilis MnSOD, but is present in the MnSOD from the eukaryote Caenorhabditis elegans. Thus, its presence might not be incidental and furthermore provides an alternative geometry for the Mn-atom coordination at the active site.

2. Materials and methods

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, Missouri, USA) or Merck AG (Darmstadt, Germany) except where otherwise indicated.

2.1. Preparation of recombinant S. equorum MnSOD

S. equorum MnSOD was overproduced in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells as a recombinant protein containing a C-terminal His6 tag. It was subsequently purified according to a previous report (Retnoningrum et al., 2017 ▸) with minor modifications, i.e. the buffer used was Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5). In brief, the enzyme was produced in LB medium containing 100 µg ml−1 ampicillin at 310 K with agitation at 150 rev min−1 and induced with 1 mM IPTG. After cell disruption, the enzyme in the soluble fraction was purified using a Ni2+–NTA cOmplete affinity column (Roche, Singapore) on an FPLC system (NGC system, Bio-Rad). Auxiliary purification (polishing) was performed with an Enrich-70 size-exclusion column (Bio-Rad). The purified protein was concentrated using a 10 kDa cutoff Macrosep centrifugal concentrator (Merck–Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.2. Enzyme-activity assays

Colorimetric and zymographic activity assays were based on the reduction of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) in the presence of riboflavin (Retnoningrum et al., 2016 ▸). Briefly, an enzyme solution in 16 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.8 was mixed with 85 µM NBT, 0.8 mM tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) and 6 µM riboflavin. The mixture was then exposed to light for 5–10 min at 310 K. The absorbance of the formazan formed was measured at a wavelength of 560 nm at room temperature (298 K). The percentage of reduction inhibition was calculated from the difference in absorbance between the blank and the sample (in the absence and the presence of the enzyme, respectively). The zymographic analysis was performed with a 12% native PAGE followed by negative staining formed by the reduction of NBT in the presence of riboflavin. The gel was immersed in 0.1 mM phosphate buffer containing 0.17 M NBT for 15 min and was subsequently rinsed with water. A solution containing 0.016 mM riboflavin and 11 mM TEMED was added to the gel. Incubation was performed in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. After rinsing with water, the gel was exposed to visible light. The presence of a clear zone at the expected band after exposure in the gel is an indication of SOD activity.

2.3. Crystallization and data collection

Initial crystal screening was performed by the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method employing a Mosquito crystallization robot system (TTP LabTech, Hertfordshire, England). Screening was performed using a protein stock solution concentration of 3.4 mg ml−1 against the Index and PEG/Ion screens from Hampton Research (Alison Viejo, California, USA), in which small crystals emerged under several conditions after a few weeks. Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained in a manual setup of the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method in which a drop consisting of 1 µl 7.4 mg ml−1 protein solution in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0 mixed with 1 µl mother-liquor solution [0.2 M magnesium chloride, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 25%(w/v) PEG 3350] was placed over 50 µl reservoir solution. The experiment was carried out in a 96-well Corning plate (Tewksbury, Massachusetts, USA) at 293 K. X-ray diffraction data were collected from an S. equorum MnSOD crystal mounted on a cryoloop and flash-cooled in a nitrogen vapour stream. The diffraction data were recorded with a Dectris PILATUS 2M detector upon exposure to an X-ray beam at 1.0 Å wavelength. The X-ray data collection was conducted on BL-5A at the Photon Factory (PF), High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK), Tsukuba, Japan.

2.4. X-ray diffraction data processing and structure determination

The X-ray diffraction data were processed (indexed, integrated and scaled) using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▸) and the CCP4 program suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▸). The phasing was performed by molecular replacement using MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 2010 ▸) employing the structure of B. subtilis MnSOD as the homology model. Model building was then continued manually with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸). Refinement of the model was performed with REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸) and phenix.refine (Afonine et al., 2012 ▸). Water molecules were gradually introduced into the (F o − F c) electron-density map using Coot at peaks in the electron density above 3.0σ and within the distance range of a hydrogen bond. Structure validation was performed with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993 ▸). The data-collection and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1 ▸. The structure has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 5x2j. Structural evaluation and comparison with the structures of MnSOD sequence homologues were performed manually with Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸). Analysis of the protein molecule was also performed using PISA (Krissinel & Henrick, 2007 ▸), ASA-view (Ahmad et al., 2004 ▸) and ProteinVolume 1.3 (Chen & Makhatadze, 2015 ▸). The structural figures were prepared with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org).

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution bin.

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | BL-5A, PF |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.00–1.40 (1.42–1.40) |

| Measured reflections | 386764 |

| Unique reflections | 40473 |

| Multiplicity | 9.6 (9.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 24.4 (3.3) |

| R merge (%)† | 7.2 (47.8) |

| R p.i.m. (%) | 2.5 (16.2) |

| CC1/2 | 0.996 (0.935) |

| Space group | P3221 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 57.36, b = 57.36, c = 105.76 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 36.21–1.40 (1.44–1.40) |

| No. of reflections | 38397 (2794) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100) |

| R factor (%) | 14.2 (20.2) |

| R free (%) | 18.5 (28.0) |

| R.m.s.d., bond lengths (Å) | 0.019 |

| R.m.s.d., bond angles (°) | 1.8 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favoured region (%) | 91.5 |

| Additional allowed region (%) | 7.4 |

| B factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 18.4 |

| Manganese | 8.6 |

| Water | 30.7 |

| PDB code | 5x2j |

R

merge =

, in which Ii(hkl) is the ith measurement and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the weighted mean of all measurements of I(hkl).

, in which Ii(hkl) is the ith measurement and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the weighted mean of all measurements of I(hkl).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Crystallization, X-ray diffraction analysis and structural analysis

From one crystallization drop, crystals of S. equorum MnSOD with two different shapes were obtained: prismatic and polygonal (Supplementary Fig. S1). During the preliminary analysis of the X-ray diffraction data, a prismatic crystal diffracted to 3.6 Å resolution (orthogonal space group P222) and a polygonal crystal to 1.86 Å resolution (trigonal space group P3221). The latter was employed for further structural analysis because it was more reproducible and diffracted to higher resolution. However, this polygonal crystal suffered from twinning, hampering analysis and processing of the diffraction data. Fortunately, one of the polygonal crystals diffracted to 1.4 Å resolution without crystallographic problems. Diffraction data from this crystal were used in the subsequent data processing and structure determination. The data-collection and structure-refinement statistics are presented in Table 1 ▸.

Further, crystallographic analysis of the crystal suggested the presence of one protein molecule in the asymmetric unit, with a Matthews coefficient V M of 2.2 Å3 Da−1 (44.6% solvent content; Kantardjieff & Rupp, 2003 ▸; Matthews, 1968 ▸). However, the dimeric form was observed upon symmetry analysis, in agreement with the presence of the enzyme dimer in solution (Retnoningrum et al., 2016 ▸). Bacterial MnSODs are mostly found in dimeric form, as shown by the structures of B. subtilis MnSOD and E. coli MnSOD, which contain four dimers (eight molecules) and two dimers (four molecules), respectively. The dimeric form of MnSOD has been proposed to be instrumental in enzyme activity and stability (Edwards et al., 2001b ▸; Whittaker & Whittaker, 1998 ▸).

3.2. Overall structure of S. equorum MnSOD and the active site

Bacterial MnSOD is a homodimeric enzyme, in which the monomer has the typical two-domain fold comprising of a helical domain and an α/β domain and containing one manganese ion (Liu et al., 2007 ▸). Their secondary-structure elements are highly conserved, with only few deviations involving surface loops and single-turn (short) helices. The structural features of the monomers are also observed in eukaryotic MnSODs, including human MnSOD, which is a tetrameric enzyme (Borgstahl et al., 1992 ▸).

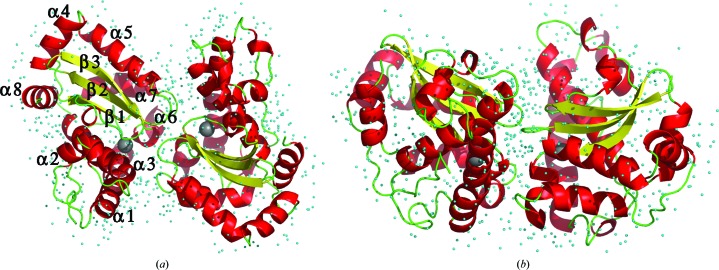

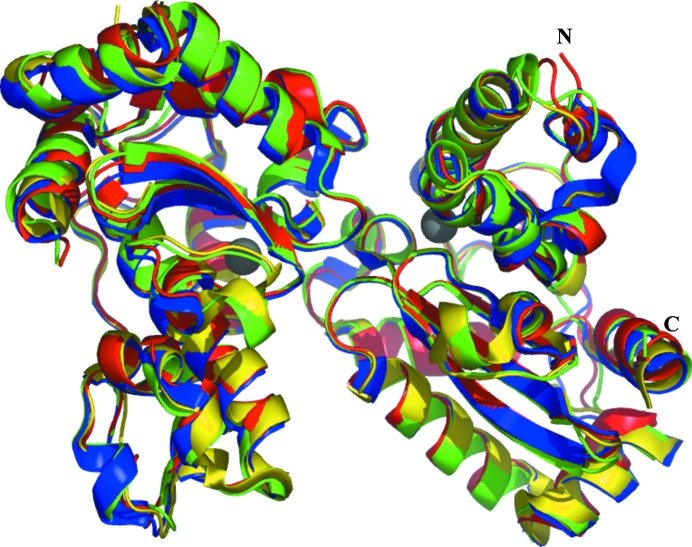

The structure of the S. equorum MnSOD monomer comprises an identical number of α-helices and β-sheets in an antiparallel arrangement similar to that of B. subtilis MnSOD (Fig. 1 ▸). The helical domain of S. equorum MnSOD consists of helices α1–α3 at corresponding positions to those of B. subtilis MnSOD in its amino-acid sequence. Furthermore, the α/β domain starts with α4 and α5 followed by the three strands β1–β3, and finally α6–α8. All of these secondary-structure elements are nearly identical to those of B. subtilis MnSOD, confirming our hypothesis that the structures of the two enzymes are nearly identical. The main-chain atoms in the overall structure of S. equorum MnSOD are superimposable with those of B. subtilis MnSOD, D. radiodurans MnSOD and E. coli MnSOD (Fig. 2 ▸), with r.m.s.d. values of 0.78, 0.79 and 0.93 Å, respectively (Table 2 ▸; Krissinel & Henrick, 2004 ▸).

Figure 1.

Top-view (a) and side-view (b) ribbon representations of the dimeric structure of S. equorum MnSOD with its secondary-structure elements in red (α-helix), yellow (β-sheet) and green (coil or loop). The Mn atom is shown as a dark grey sphere and the water molecules are shown as cyan dots.

Figure 2.

Structural comparison between MnSODs from S. equorum (red), B. subtilis (blue), E. coli (green) and D. radiodurans (yellow). The structures are presented as ribbons and the Mn atom is shown as a dark grey sphere. The N- and C-termini are indicated.

Table 2. Structural comparison of S. equorum MnSOD with its homologues.

| S. equorum | B. subtilis | E. coli | D. radiodurans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 5x2j | 2rcv | 1vew | 2ce4 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Structural alignment | ||||

| R.m.s.d. (Å) | — | 0.7859 | 0.9259 | 0.7970 |

| No. of residues aligned | 198 | 197 | 196 | 196 |

| Quality normalized | — | 0.1147 | 0.2149 | 0.4409 |

| Protein volume calculation | ||||

| Molecular volume (Å3) | 26795.5 | 26517.1 | 27798.5 | 27212.5 |

| Packing density | 0.752 | 0.747 | 0.739 | 0.746 |

| Void volume (Å3) | 6656.5 | 5717.9 | 7268.8 | 6914.4 |

| van der Waals volume (Å3) | 20139.0 | 19799 | 20529.7 | 20298.1 |

| PISA calculation | ||||

| Surface area (Å2) | 17590 | 17353 | 17680 | 17140 |

| Buried area (Å2) | 1770 | 1710 | 1715 | 1810 |

| Buried/surface area (%) | 10.1 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 10.6 |

Furthermore, all of the previously reported interactions during dimer formation (Edwards et al., 1998 ▸; Liu et al., 2007 ▸) are present: for instance, the glutamate bridge between Glu164 (S. equorum MnSOD amino-acid sequence numbering) of molecule A (Glu164-A) and that of molecule B (Glu164-B). Glu164-A is stabilized by the interaction of its O∊ atom with the Nδ atom of His165-B (and, vice versa, of Glu164-B with His165-A). An interaction of the N∊ atom of His31-A with the Oδ atom of Tyr168-B is also present in the dimer interface. This His31-A/Tyr168-B pair is highly conserved and has been proposed to guide the substrate into the active site (Whittaker & Whittaker, 1998 ▸). Other interactions in the dimer interface involve Ser126-A with Ser126-B and the water-mediated interaction of Asn145-A with Asn145-B.

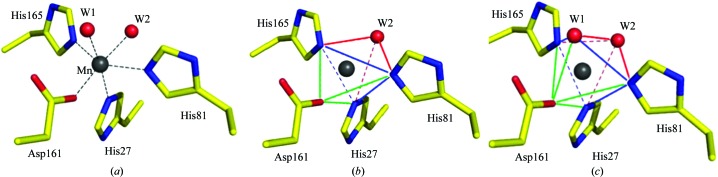

His165 is one of the three histidine residues (the others are His27 and His81) that coordinate the manganese at the active site of the enzyme. The Mn atom is also coordinated by Asp161 and two water molecules, W1 and W2, which are in the axial positions opposite His27 and Asp161, respectively (Fig. 3 ▸ a). However, while the water molecule W2 is observed in the active-site region in the structures of B. subtilis MnSOD (1.8 Å resolution), E. coli MnSOD (2.1 Å resolution) and D. radiodurans MnSOD (2.2 Å resolution), water molecule W1 is absent. Spectroscopic and structural study of E. coli MnSOD suggest a trigonal bipyramidal geometry of the manganese in the active site (Edwards et al., 1998 ▸). In S. equorum MnSOD this coordination is achieved with the triad His27–His81–His165, Asp161 and water molecule W2 (Fig. 3 ▸ b). Further inspection revealed that the histidine triad, the aspartate, the manganese and the water molecule W1 may form a square-pyramidal geometry (Fig. 3 ▸ c) and, when W2 is involved, form a distorted octahedral geometry. This situation has not previously been identified owing to the absence of the water molecule W1 from the structures of S. equorum MnSOD bacterial homologues (MnSODs from B. subtilis, E. coli and D. radiodurans).

Figure 3.

Active site of S. equorum MnSOD in the presence of the Mn atom and water molecules W1 and W2 (a), with possible trigonal bipyramidal geometry involving water molecule W2 (b) and square tetahedral geometry involving water molecule W1 (and orthogonal geometry when W2 is involved) (c). The trigonal and tetragonal squares are shown as blue lines, the interactions that form the trigonal and tetragonal pyramidal geometries are shown as red lines, and the interactions to complete the trigonal bipyramidal and orthogonal geometries are shown as green lines.

The presence of W1 in S. equorum MnSOD may not be artificial because its position is conserved in the structure of azide-bound C. elegans MnSOD (1.8 Å resolution; Hunter et al., 2015 ▸), in which the W1 position is occupied by the azide. The presence of the azide completes the distorted octahedral coordination, thereby supporting the 5–6–5 manganese coordination shift during the reaction, as previously proposed for the FeSOD from E. coli (Lah et al., 1995 ▸). In this respect, the structure of S. equorum MnSOD probably represents the condition in which the substrate is bound.

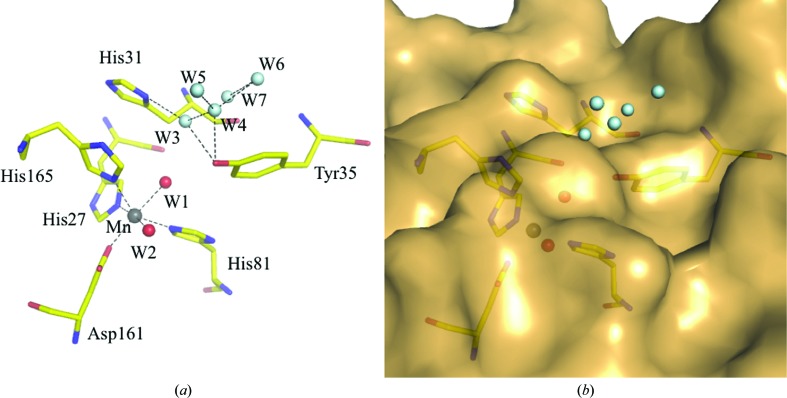

In addition, another water molecule (W3) that interacts with His31 (Nδ) and Tyr35 (Oδ) is present 3.73 Å away from water molecule W1. His31 plays a role in the aforementioned interactions in the dimer interface. A water relay involving W1 and W3 in the S. equorum MnSOD structure may lead to the open space outside the enzyme dimer (Fig. 4 ▸), suggesting a passage for the superoxide substrate to enter or for the peroxide product to leave the active-site cavity. This water relay has also been observed in the structure of C. elegans MnSOD (Hunter et al., 2015 ▸).

Figure 4.

The water relay in the active site of S. equorum MnSOD to the open space involving W1–W3. His27, His81, His165 and Asp165 are the residues that coordinate the Mn atom, while His31 and Tyr35 are the residues that reside on top of the active-site cavity. His31 has been hypothesized to guide the substrate into the active site. Cyan spheres are water molecules (including W3) on the outer concave surface of the active site.

Further study of the Mn atom in the active site of MnSOD shows its relation to FeSOD because of their structural resemblance and cambialistic character, although the electron configuration of iron ([Ar] 4s 2 3d 6) differs from that of manganese ([Ar] 4s 2 3d 5). The study of MnSODs from Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria and Candida albicans cytosol reveals reduced (Mn2+) and oxidized (Mn3+) states of the manganese when no reaction takes place (the so-called rest state; Sheng et al., 2011 ▸). In this respect, Mn3+ may occur as five-coordinate Mn3+ or six-coordinate L-Mn3+ (with hydroxide as the sixth ligand). Spectroscopic study of bacterial MnSOD suggests that manganese is mostly found in its reduced state, which is supported by its structure. In addition, the activity of the MnSOD with the six-coordinate L-Mn3+ species is prone to reduction by ascorbate (Sheng et al., 2011 ▸). This may be correlated with the observed reduced activity of S. equorum MnSOD in the presence of reducing agents (Indrayati et al., 2014 ▸).

Finally, Gln146 in S. equorum MnSOD, at a position corresponding to that in E. coli MnSOD, plays an important role in maintaining the hydrogen-bonding network in the active site (Edwards et al., 2001a ▸). In S. equorum MnSOD and B. subtilis MnSOD, this residue resides in the surface loop (residues 151–155; S. equorum MnSOD amino-acid sequence numbering) that connects β2 and β3. This loop is five amino-acid residues shorter than the loop in E. coli MnSOD and D. radiodurans MnSOD. Consequently, the active site in the MnSODs from S. equorum and B. subtilis may be less accessible from the solvent, which may impact the reaction turnover. Solvent-accessibility analysis (Krissinel & Henrick, 2007 ▸) indicated that the Gln146 and the neighbouring Asn145 are buried in the MnSODs from S. equorum and B. subtilis, while the corresponding residues in the MnSODs from E. coli and D. radiodurans are accessible.

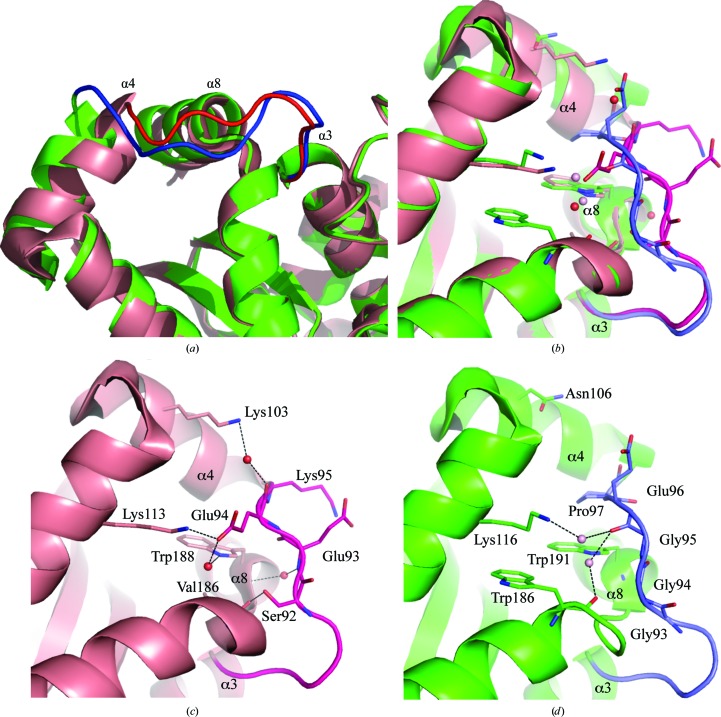

3.3. Structural comparison to B. subtilis MnSOD

Structural comparison of S. equorum MnSOD with B. subtilis MnSOD was motivated by their remarkable differences in enzyme activity and stability, despite the high similarity in their amino-acid sequences. The only obvious difference between the structures of S. equorum MnSOD and B. subtilis MnSOD is the stretch of residues Asn91–Val99, which is the region that connects the helical and α/β domains (Fig. 5 ▸). The corresponding stretch in B. subtilis MnSOD is only one amino-acid residue longer (Leu89–Pro97; B. subtilis MnSOD amino-acid sequence numbering); thus, the loop extends slightly into the solvent. Furthermore, the shorter loop in S. equorum MnSOD causes the first helix of the α/β domain (α4) to shift inward and thereby interact better with α8, which is the last helix in this domain (Figs. 5 ▸ a and 5 ▸ b). The shift allows additional interaction between Oγ of Ser92 and the carbonyl backbone of Val186, a water-mediated interaction between the amino-acid backbone of Glu93 and Trp188, and finally interaction of the O∊ atom of Glu94 and the Nζ atom of Lys113. The loop itself is stabilized by side-chain interaction of the O∊ atom of Glu93 and the Nζ atom of Lys95 (Fig. 5 ▸ c). These interactions may increase the rigidity of the α/β domain. The active site of the enzyme is located at the interface of the helical and α/β domains, which both contribute equally to coordination of the Mn atom and the reaction. Thus, the increase in the latter domain may make the enzyme resistant to denaturation and improve its thermal stability. In addition, in the structures of other S. equorum MnSOD structural homologues (MnSODs from D. radiodurans and E. coli) the first helix in the α/β domain adopts an identical position to that in B. subtilis MnSOD.

Figure 5.

(a) Differences in the structures of MnSODs from S. equorum (salmon) and B. subtilis (green). The loop connecting α3 and α4 in S. equorum MnSOD (red) is shorter than that in B. subtilis MnSOD (blue), resulting in a structural shift of α4 towards α8. (b) Residues in the loop connecting the α3 and α4 (Glu93–Lys95), α4 (Lys113) and α8 (Trp188) helices come into proximity for interactions as a result of the structural shift. Details of interactions in the structure of S. equorum MnSOD (c) and their corresponding amino acids in that of B. subtilis MnSOD (d) as a comparison.

Further evaluation of individual amino-acid residues using ASA-view suggested that the amino-acid composition of S. equorum MnSOD is slightly different from that of B. subtilis MnSOD (Supplementary Fig. S3). Overall, S. equorum MnSOD contains more charged residues than B. subtilis MnSOD. Most importantly, more charged residues in S. equorum MnSOD are accessible to the solvent, which may correspond to a slight increase in the van der Waals interaction (75.2%) in S. equorum MnSOD compared with B. subtilis MnSOD (74.7%). Furthermore, residues involved in the dimer interface are mostly conserved; thus, not many differences were found during analysis using PISA (Krissinel & Henrick, 2007 ▸; Table 2 ▸).

S. equorum MnSOD has been shown to have two melting temperatures (T m) at around 325 and 341 K, which correspond to dimer dissociation and unfolding of the monomer, respectively (Retnoningrum et al., 2016 ▸). However, while the dimeric form has been associated with enzyme activity (Whittaker & Whittaker, 1998 ▸), the relationship between the dimeric form and enzyme stability has not been established. The crystal structure of S. equorum MnSOD suggests that enzyme stability might not be owing to the dimeric form because very little variation was observed compared with B. subtilis MnSOD. The S. equorum MnSOD structure shows additional interactions from the shorter interdomain-connecting loop in the monomer structure. Slightly higher charged residues on the surface of the enzyme molecule may improve its interaction with the aqueous environment, but this has not yet been confirmed.

4. Conclusion

We have successfully elucidated the structure of S. equorum MnSOD, the first example of an MnSOD from the Staphylococcus genus. The structure may provide an explanation on a molecular basis for the differences in the characteristics of S. equorum and B. subtilis MnSOD, two close homologues that share high homology in their amino-acid sequences. Furthermore, the structure of S. equorum MnSOD contains an additional water molecule that is absent from the structures of its homologues that may shed light on the exact mechanisms of the enzymatic reaction.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: hybrid manganese superoxide dismutase from Staphylococcus equorum and S. saprophyticus, 5x2j

Supplementary Figures.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X18001036/or5002sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

The X-ray diffraction data-acquisition experiments were performed with the approval of the Photon Factory Advisory Committee. We thank Professor George I. Makhatadze of the School of Science, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, USA for assisting with the protein volume analysis and Dr H. J. Doddema for his help in editing the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Direktorat Jenderal Pendidikan Tinggi grant to Debbie Retnoningrum. Institut Teknologi Bandung grant to Debbie Retnoningrum. Kagawa University grant .

References

- Abreu, I. A. & Cabelli, D. E. (2010). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1804, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Acton, Q. A. (2013). Editor. Oligopeptides: Advances in Research and Application. Atlanta: ScholarlyEditions.

- Afonine, P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Echols, N., Headd, J. J., Moriarty, N. W., Mustyakimov, M., Terwilliger, T. C., Urzhumtsev, A., Zwart, P. H. & Adams, P. D. (2012). Acta Cryst. D68, 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S., Gromiha, M. M., Fawareh, H. & Sarai, A. (2004). BMC Bioinformatics, 5, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Borgstahl, G., Parge, H., Hickey, M., Beyer, W., Hallewell, R. & Tainer, J. (1992). Cell, 71, 107–118. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. & Makhatadze, G. (2015). BMC Bioinformatics, 16, 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dennis, R. J., Micossi, E., McCarthy, J., Moe, E., Gordon, E. J., Kozielski-Stuhrmann, S., Leonard, G. A. & McSweeney, S. (2006). Acta Cryst. F62, 325–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R. A., Baker, H. M., Whittaker, M. M., Whittaker, M. M., Jameson, G. B. & Baker, E. N. (1998). J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 3, 161–171.

- Edwards, R. A., Whittaker, M. M., Whittaker, J. W., Baker, E. N. & Jameson, G. B. (2001a). Biochemistry, 40, 15–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R. A., Whittaker, M. M., Whittaker, J. W., Baker, E. N. & Jameson, G. B. (2001b). Biochemistry, 40, 4622–4632. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hunter, G. J., Trinh, C. H., Bonetta, R., Stewart, E. E., Cabelli, D. E. & Hunter, T. (2015). Protein Sci. 24, 1777–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Indrayati, A., Asyarie, S., Suciati, T. & Retnoningrum, D. S. (2014). Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 6, 440–445.

- Kantardjieff, K. A. & Rupp, B. (2003). Protein Sci. 12, 1865–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2256–2268. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lah, M., Dixon, M., Pattridge, K., Stallings, W., Fee, J. & Ludwig, M. (1995). Biochemistry, 34, 1646–1660. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst. 26, 283–291.

- Liu, P., Ewis, H. E., Huang, Y.-J., Lu, C.-D., Tai, P. C. & Weber, I. T. (2007). Acta Cryst. F63, 1003–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lods, L. M., Dres, C., Johnson, C., Scholz, D. B. & Brooks, G. J. (2000). Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 22, 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maritim, A. C., Sanders, R. A. & Watkins, J. B. (2003). J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 17, 24–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miller, A.-F. (2012). FEBS Lett. 586, 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Retnoningrum, D. S., Arumsari, S., Artarini, A. & Ismaya, W. T. (2017). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 98, 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Retnoningrum, D. S., Rahayu, A. P., Mulyanti, D., Dita, A., Valerius, O. & Ismaya, W. T. (2016). Protein J. 35, 136–144. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Y., Stich, T. A., Barnese, K., Gralla, E. B., Cascio, D., Britt, R. D., Cabelli, D. E. & Valentine, J. S. (2011). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 20878–20889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang, W., Ma, T., Zhang, B., Yao, N., Li, M., Cui, L., Li, G., Ma, Z. & Cheng, J. (2014). Sci. Rep. 4, 7284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, M. M. & Whittaker, J. W. (1998). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 22188–22193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: hybrid manganese superoxide dismutase from Staphylococcus equorum and S. saprophyticus, 5x2j

Supplementary Figures.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X18001036/or5002sup1.pdf