Abstract

Background

Allergen‐specific immunotherapy can induce long‐term suppression of allergic symptoms, reduce medication use, and prevent exacerbations of allergic rhinitis and asthma. Current treatment is based on crude allergen extracts, which contain immunostimulatory components such as β‐glucans, chitins, and endotoxin. Use of purified or recombinant allergens might therefore increase efficacy of treatment.

Aims

Here, we test application of purified natural group 1 and 2 allergens from Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Der p) for subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) treatment in a house dust mite (HDM)‐driven mouse model of allergic asthma.

Materials and methods

HDM‐sensitized mice received SCIT with crude HDM extract, a mixture of purified Der p1 and 2 (DerP1/2), or placebo. Upon challenges, we measured specific immunoglobulin responses, allergen‐induced ear swelling response (ESR), airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and inflammation in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and lung tissue.

Results

ESR measurement shows suppression of early allergic response in HDM‐SCIT– and DerP1/2‐SCIT–treated mice. Both HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT are able to suppress AHR and eosinophilic inflammation. In contrast, only DerP1/2‐SCIT is able to significantly suppress type 2 cytokines in lung tissue and BAL fluid. Moreover, DerP1/2‐SCIT treatment is uniquely able suppress CCL20 and showed a trend toward suppression of IL‐33, CCL17 and eotaxin levels in lung tissue.

Discussion

Taken together, these data show that purified DerP1/2‐SCIT is able to not only suppress AHR and inflammation, but also has superior activity toward suppression of Th2 cells and HDM‐induced activation of lung structural cells including airway epithelium.

Conclusions

We postulate that treatment with purified natural major allergens derived from HDM will likely increase clinical efficacy of SCIT.

Keywords: Allergen‐specific immunotherapy, allergic asthma, house dust mites, purified natural Der p1 and 2, tolerance induction

1. INTRODUCTION

Allergen‐specific immunotherapy (SIT) has been used for the treatment of allergic disorders for over a century.1 Specific immunotherapy (SIT) has been shown to induce durable immunological changes in response to the allergen, through generating neutralizing antibodies, through suppressing numbers and activity of allergen‐specific Th2 cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), and by inducing regulatory T‐cell activity.2 Successful SIT has been associated with enhanced release of IL‐10 in PBMC cultures restimulated with allergen,3 serum‐dependent suppression of cross‐presentation by B cells,4 and selective loss of those T‐cell clones with allergen‐epitope specificities that are increased in atopic individuals compared to healthy controls.5, 6 Specific immunotherapy (SIT) induces long‐term tolerance to the allergen, as evidenced by the absence of allergic manifestations upon repeated allergen challenges.1

Current SIT regimens routinely employ a crude extract of the allergen for injection, subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) or tablet and droplet formulation, sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). Crude extracts contain the full array of major allergens that a patient can be sensitized to, which increases likelihood of therapeutic efficacy in patients without the need of component‐resolved diagnosis prior to treatment. Additionally, crude extracts also contain numerous nonprotein constituents such as chitins, β‐glucans, and endotoxins, all of which can act on innate immune cells in a pro‐inflammatory fashion, which might interfere with the tolerance‐inducing capacity required for successful therapy.7 In contrast, use of purified proteins allows for treatment with specific allergens in the absence of such components contained within extracts.8 This is expected to enhance SIT efficacy by more efficiently inducing a tolerogenic response due to the absence of TLR agonists during allergen administration, harnessing an immunoregulatory phenotype of the allergen‐presenting cell upon SCIT.1 Moreover, use of purified allergens in combination with a component‐resolved diagnosis of sensibilization patterns holds the promise of personalized intervention strategies in immunotherapy.8 However, it is currently unknown whether purified allergens are a more efficient treatment modality than full allergen extracts.

House dust mite (HDM) is the most prominent source of indoor exposure to allergens and is a cause for allergic rhinitis and asthma.9 The HDM species Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Der p) has at least 23 major allergens9 that are thought to contribute to allergic sensitization through their proteolytic activity, activating cells of the innate immune system and priming an adaptive type 2 immune response.2, 9 In the MAS prospective birth cohort, sensitization patterns for HDM allergens were studied into detail by component‐resolved analysis.10 Herein, specific IgE (spIgE) for Der p1, 2, and 23 can be detected before sensitization to any of the other major allergens. Moreover, sensitization to Der p1, 2, and 23 allergens has the highest prevalence, with more than half of the 20‐year‐old individuals having spIgE to group 1 and 2 allergens.10 Interestingly, early onset of sensitization to group 1, 2, or 23 allergens was associated with sensitization to more HDM allergens and with allergic rhinitis and asthma at school age, indicating the clinical relevance of these sensitization patterns.10 Treatment options for HDM allergy include allergen avoidance and SIT.11 However, HDM extracts are variable in content of allergens,12, 13 and stability is limited.14 Given the fact that sensitization to Der p1 and 2 identifies more than 95% of HDM‐allergic individuals9, 13 and their causal role in early sensitization,10 SIT with purified Der p1 and 2 might be a more attractive therapeutic approach compared to the use of HDM extracts.

Here, we test the hypothesis that treatment with natural purified Der p1 and 2 is an effective treatment in inducing a protective neutralizing antibody response and in suppressing allergic inflammation in a mouse model of HDM‐driven allergic asthma. We find that SCIT with a mixture of Der p1 and 2 is superior to extract in suppressing Th2 cell activity and inducing neutralizing antibodies, and equally capable of suppressing manifestations of allergic airway inflammation upon challenges in sensitized mice.

2. METHODS

2.1. Purification of crude HDM extracts

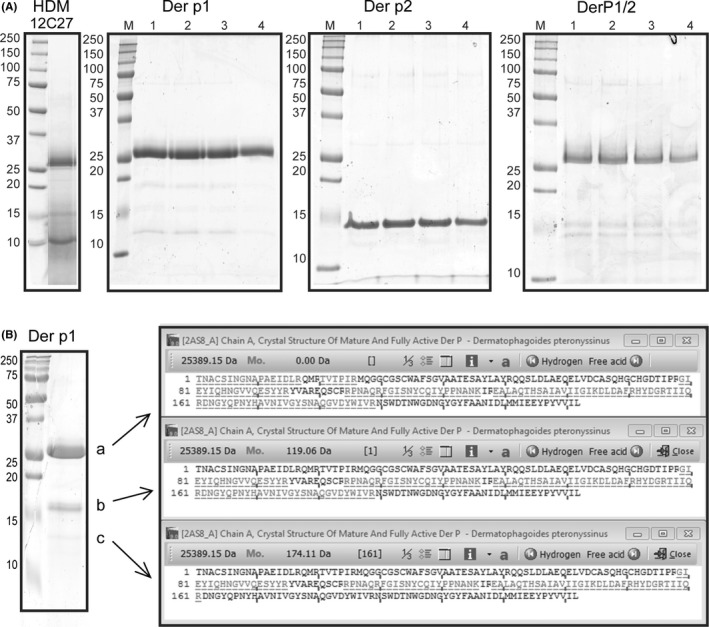

Freeze‐dried Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extracts were prepared from whole mite bodies (12C27, Citeq biologics, Groningen, the Netherlands) and contained 28.5 mg purified Der p1 and 1.8 mg purified Der p2/g dry weight (ELISA), 439 mg/g protein (BCA), pyretic activity of 5.8 × 106 EU/g (endotoxin assay), and <3 × 103 KVE/g bioburden (TSA). Purification of groups 1 and 2 from Der p was performed by ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography as previously described.15, 16, 17, 18 Purified proteins were separated by SDS‐PAGE to evaluate purity and stability (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evaluation of crude extract house dust mite (HDM) and naturally purified Der p1 and 2. A, Purified proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate‐polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis SDS‐PAGE in four different conditions: 1, zero hour; 2, 46‐h incubation at 4°C; 3, 46‐h incubation at room temperature; 4, 46‐h incubation at 37°C. On the left, the marker (M) is consistent throughout all gels. B, left: Analysis of purified Der p1 by PAA gel electrophoresis identifying three smaller fragments, sized 25, 17, and 14 kDa. B, right: Protein BLAST against full‐length Der p 1 of peptides identified by Maldi‐TOF from purified bands a, b, and c

2.2. Experimental animals

BALB/cByJ mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (L'Arbresle, France) at an age of 6 to 8 weeks and housed in individually ventilated cages (IVC). Animal housing and experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of and after written approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Groningen. All groups consisted of eight female mice.

2.3. Allergic asthma treatment protocol

All mice received injections of 5 μg crude extract HDM adsorbed to 2.25 mg Alum (Imject, Pierce) in 100 μL PBS (Figure 2A). Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) was performed by three injections on alternate days,19 using 250 μg crude extract HDM, or naturally purified Der p1 and 2 in a 50/1 ratio (100 μg DerP1/2), applied either in 100 μL PBS or as freshly prepared emulsions of the purified DerP1/2 solution in SAINT lipids (Synvolux, the Netherlands), at a concentration of 5, 10, or 20 μg DerP1/2 in, respectively, 75, 150, or 300 nmol SAINT (Figure 6B). Challenges were performed by intranasal installation of 25 μg HDM. Hereafter, airway responsiveness was determined, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), lungs, and blood were collected and stored for analyses.

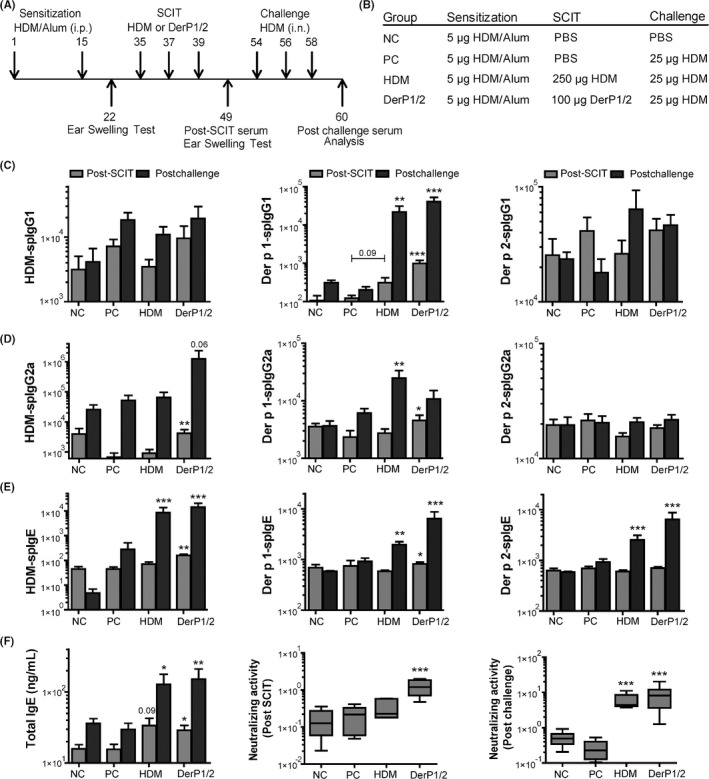

Figure 2.

Overview and immunoglobulin response after subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) treatment. A, Outline of the SCIT protocol. B, Outline of the treatment groups. C, House dust mite (HDM) specific IgG1, Der p1 specific IgG1, and Der p2 specific IgG1 levels measured in sera taken after SCIT and after challenges (arbitrary units (AU)/mL, post‐SCIT and postchallenges). D, House dust mite (HDM)‐spIgG2a, Der p1‐spIgG2a, and Der p2‐spIgG2a levels measured in sera taken before and after challenges (AU/mL, post‐SCIT and postchallenges). E, House dust mite (HDM)‐spIgE, Der p1‐spIgE, and Der p2‐spIgE levels measured in sera taken before and after challenges (AU/mL, post‐SCIT and postchallenges). F, Total IgE (ng/mL) levels measured in sera taken before and after challenges (ng/mL, post‐SCIT and postchallenges), and the neutralizing activity plotted as ratio of Der p1‐spIgG1/Der p1‐spIgE levels in post–SCIT‐sera (middle) and post–challenge‐sera (right). In Figure 1C‐F, values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). The neutralizing activities in Figure 1F are expressed in the box‐and‐whisker plots (min‐max). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared to PC at the same time point. NC: Negative control, PBS challenged; PC: positive control, HDM challenged; HDM and DerP1/2: different SCIT‐treated mice, HDM challenged

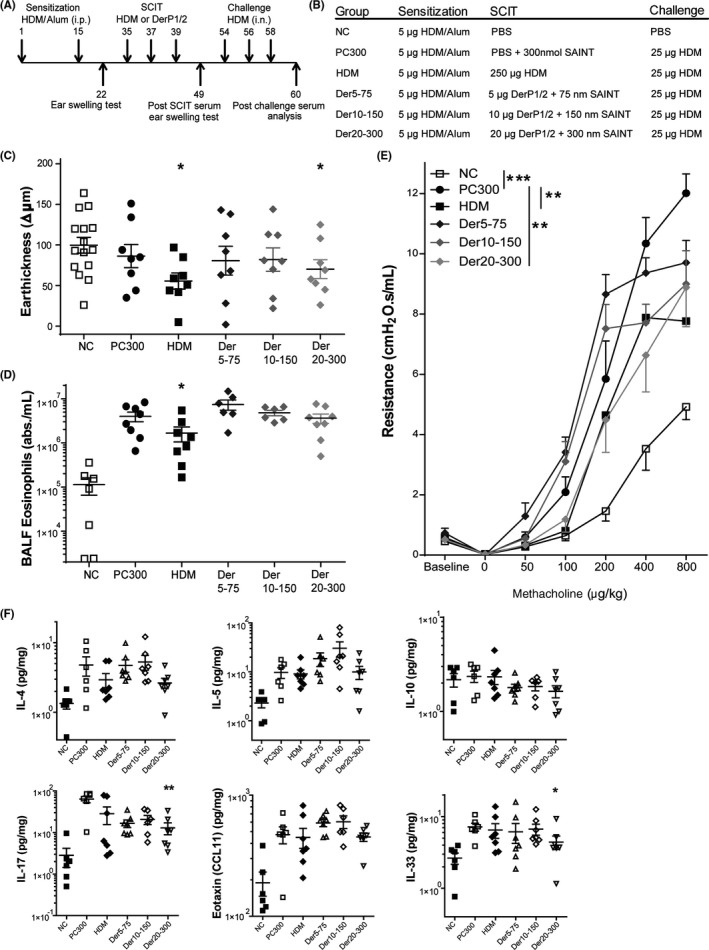

Figure 6.

Overview of relevant experimental parameters measured after subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) treatment containing SAINT lipids. A, Outline of the SCIT protocol. B, Outline of the treatment groups. C, IgE‐dependent allergic response plotted as net ear thickness (μm) 2 h after house dust mite (HDM) injection (0.5 μg) in the right ear and PBS in the left ear as a control, performed after SCIT. Placebo‐SCIT–treated mice were plotted together as controls (NC and PC). D, Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) eosinophils, plotted as absolute numbers/mL; mean ± SEM). E, Airway hyperreactivity (AH) was measured by FlexiVent and plotted as airway resistance (R in cmH2O.s/mL). F, Overview of cytokine profile after SCIT treatments, measured in lung tissue dissolved in Luminex buffer; IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐10 (pg/mg) in lung tissue of HDM‐treated, DerP1/2‐treated and sham‐SCIT–treated mice. Second row; IL‐17, eotaxin (CCL11), and IL‐33 levels (pg/mg), quantified via Luminex in lung tissue. Concentrations (pg/mg) are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared to PC. NC: Negative control, PBS challenged; PC: Positive control, HDM challenged; HDM, DerP1/2: different SCIT treatments, HDM challenged

2.4. Ear swelling response (ESR)

Before and after SCIT treatment, an ear swelling test (EST) was performed to evaluate the early‐phase response to HDM to test for allergic sensitization, as previously described.7, 19

2.5. Measurement of airway hyperreactivity to methacholine

Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) was assessed by measuring airway resistance (R in cmH2O.s/mL) and lung compliance (C in mL/H2O) in response to intravenous administration of increasing doses of methacholine (Sigma‐Aldrich, MO).19, 20 Next, AHR was expressed as the effective dose of methacholine required to induce a R of 3 cmH2O.s/mL (ED3).

2.6. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

Lungs were lavaged, and cytospin preparations were made according to previous published protocols.19

2.7. T‐cell responses: restimulation of lung cells

Lung single cell suspensions (5 × 105/well) were stimulated for 5 days in RPMI1640 with 0 or 10 μg of DerP1/2 per well, and supernatant was stored in triplo (−80°C). ELISA determined the concentrations of IL‐5, IL‐10, IL‐13 and IFN‐γ, according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Pharmingen, CA).

2.8. Analysis of cytokine levels in lung tissue

The right superior lobe was used for measurement of total protein, and concentrations of IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐10, IL‐13, IL‐17, IL‐33, IFN‐γ, eotaxin/CCL11, TARC/CCL17, and MIP3‐α/CCL20 were measured using a MILLIPLEX Map Kit (Merck Millipore Corp., Germany) and analyzed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.9. HDM and Der p1 and Der p2 specific Immunoglobulins

Blood was collected at several time points in the experiment (pre‐ and postserum). House dust mite (HDM)‐spIgE, Der p1‐spIgE and p2‐spIgE, Der p1‐spIgG1, and Der p1‐spIgG2a levels were measured by ELISA in a similar protocol as described previously7 and in Table S1.

2.10. Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The Mann‐Whitney U test was used to analyze the results, and P < .05 was considered significant. Within the AHR measurements, a generalized estimated equation (GEE) analysis was used, using SPSS Statistics 20.0.0.2.21 Nonparametric Spearman's correlations were performed in Figure 5D,E.

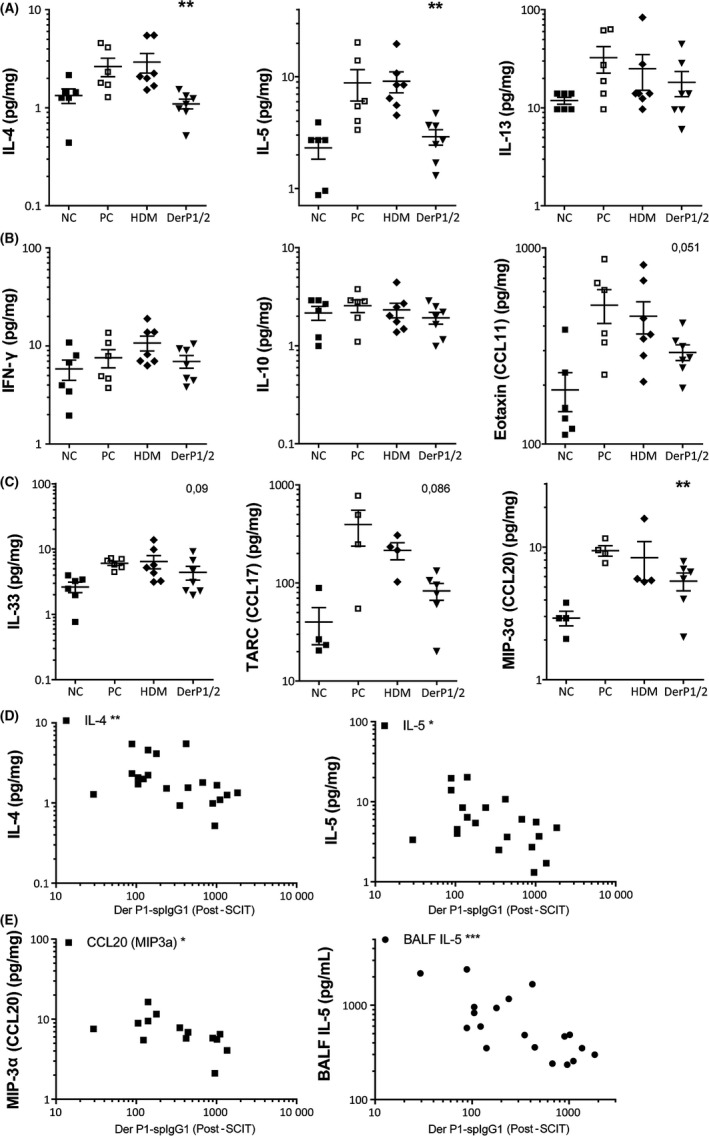

Figure 5.

Overview of cytokine profile after subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) treatments, measured in lung tissue dissolved in Luminex buffer. A, Type 2 inflammatory cytokines IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐13 (pg/mg) in lung tissue of house dust mite (HDM)‐treated, DerP1/2‐treated, and sham‐SCIT–treated mice. B, IFN‐γ, IL‐10, and eotaxin/CCL11 levels (pg/mg) quantified via Luminex in lung tissue. C, Indicators of the activation of the innate immune system, IL‐33, TARC/CCL17, and MIP3a/CCL20 in lung tissue after HDM challenges. D, Nonparametric Spearman's correlations of post‐SCIT Der p1‐spIgG1 vs lung cytokines IL‐4 (r = −.535) and IL‐5 (r = −.434). E, Nonparametric Spearman's correlations of post‐SCIT Der p1‐spIgG1 vs lung CCL20 (r = −.583) and BALF IL‐5 (r = −.685). Concentrations (pg/mg) are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared to PC. NC: Negative control, PBS challenged; PC: positive control, HDM challenged; HDM and DerP1/2: different SCIT treatments, HDM challenged

See additional methods descriptions in the online supplemental methods.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Preparation, stability, and purity of natural Der p1 and Der p2

To establish a purified DerP1/2 vaccine, we optimized biochemical purification from aqueous extracts of whole mite cultures and analyzed protein stability (Figure 1A). Both Der p1 and 2 are stable for prolonged period of time, with minor loss of protein intensity after 46 hours of incubation at 37°C. Analysis of Der p1 revealed the presence of smaller fragments, sized 25 kDa (a), 17 kDa (b), and 14 kDa (c, Figure 1B). These fragments correspond to Der p1 breakdown products given the endogenous cysteine protease activity of Der p1.11, 12 Maldi‐TOF analysis on these fragments confirmed their identity as Der p1 peptides (Figure 1B). Using these Der p1 and 2 batches, we generated a DerP1/2 vaccine by mixing in a 50:1 w/w ratio.

3.2. DerP1/2‐SCIT enhances HDM‐spIgG2a levels

Next, we aimed to test whether purified Der p1 and 2 proteins showed clinical efficacy in our SIT model. House dust mite (HDM)‐sensitized mice received SCIT with DerP1/2 or HDM, or PBS control, followed by HDM challenges to evaluate whether the allergic response is suppressed by SCIT (Figure 2A,B). As SCIT induces a neutralizing antibody response,1 we evaluated spIgG1, and spIgG2a after SCIT (post‐SCIT) and after challenges (postchallenge, Figure 2C,D). SCIT with either DerP1/2 or HDM did not affect HDM‐spIgG1 levels after treatment, or at the time of challenges. In contrast, only DerP1/2‐SCIT was able to induce a significantly increased HDM‐spIgG2a response, at both time points.

3.3. DerP1/2 and HDM‐SCIT enhance Der p1‐spIgG1 and Der p1‐spIgG2a

As we used purified Der p1 and 2, we also analyzed Der p1 and 2 specific immunoglobulins. Here, we observed increased Der p1‐spIgG1 levels after DerP1/2‐SCIT (Figure 2C). Subsequent challenges resulted in increased Der p1‐spIgG1 levels in both HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT groups.

For Der p1‐spIgG2a, we observed a significant increase after DerP1/2‐SCIT; while in the HDM‐SCIT group, increased Der p2‐spIgG2a levels were only detected after allergen challenges (Figure 2D). Der p2‐spIgG1 or Der p2‐spIgG2a responses were not observed in any of the groups.

3.4. Specific IgE responses after DerP1/2‐SCIT and HDM‐SCIT

Remarkably, most of the positive controls failed to induce a sufficiently high IgE response, visualized in the total IgE and HDM‐spIgE levels plotted in Figure 2E,F. Therefore, when both HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT groups were compared to these positive controls, we found significant increases at both time points. Also, levels of Der p1‐spIgE and 2‐spIgE were significantly increased after both HDM and DerP1/2‐SCIT compared to controls (Figure S1A).

Clinical efficacy of SIT is associated with the neutralizing capacity of the spIgGs,4 while symptom score in allergic asthma is inversely correlated to the ratio of spIgG over spIgE,22 indicating the relevance of IgG response induced during SIT. Therefore, we calculated the changes in the ratio of Der p1‐spIgG1 over Der p1‐spIgE and compared between groups (Figure 2F). We find significantly increased spIgG/spIgE ratios both before and after challenges with DerP1/2‐SCIT compared to positive controls. House dust mite (HDM)‐SCIT mice, however, only display an increased IgG/IgE ratio after HDM challenges, but not after SCIT. A complete overview of all ratios is plotted in Figure S1B. These analyses reveal that Der p1‐spIgG1 is the main isotype of neutralizing antibodies induced by SCIT in our experiment.

3.5. HDM‐SCIT reduces the early‐phase response to HDM

Next, we aimed to evaluate whether SCIT protected against the early IgE‐mediated responses upon challenges. To this end, we performed an ear swelling test (EST) by HDM injection before and after SCIT. In HDM‐sensitized mice, intradermal HDM injection resulted in a positive ear swelling, confirming allergic sensitization (Figure S2A). The EST after SCIT resulted in a significantly decreased swelling in HDM‐SCIT mice as compared to controls (Figures 3A, S2B). The suppression of swelling in DerP1/2‐SCIT mice, however, was less substantial and showed a trend toward significance.

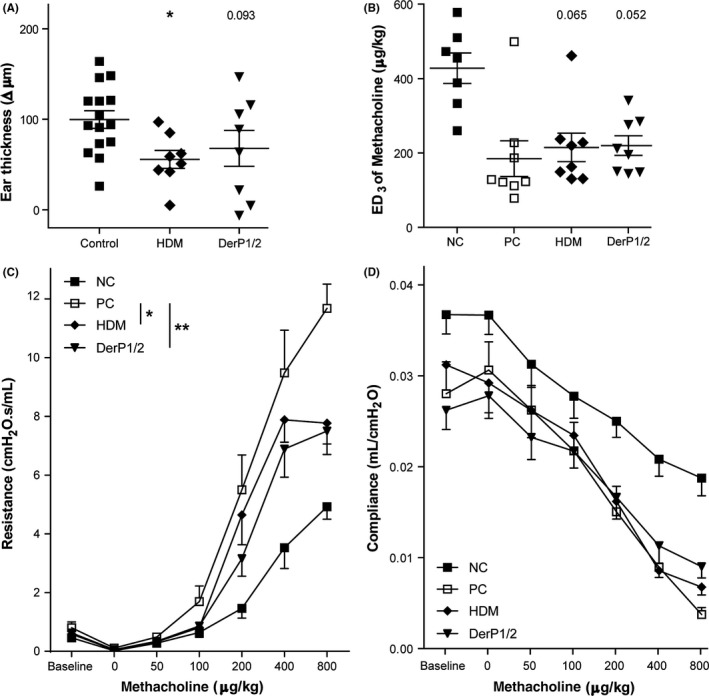

Figure 3.

Clinical manifestations after subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) treatment. A, IgE‐dependent allergic response plotted as net ear thickness (μm) 2 h after house dust mite (HDM) injection (0.5 μg) in the right ear and PBS in the left ear as a control, performed after SCIT. Placebo‐SCIT–treated mice were plotted together as controls (NC and PC). B, Effective dose (ED) of methacholine, when the airway resistance reaches 3 cmH2O.s/mL (ED3). C, Airway hyperreactivity (AH) was measured by FlexiVent and plotted as airway resistance (R in cmH2O.s/mL) and as (D) airway compliance (C in mL/cmH2O). Absolute values are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared to PC. NC: Negative control, PBS challenged; PC: positive control, HDM challenged; HDM and DerP1/2: different SCIT treatments, HDM challenged

3.6. DerP1/2‐SCIT and HDM‐SCIT suppress airway hyperresponsiveness

To evaluate whether treatment protected against phenotypes of asthma, we assessed the effect of SCIT on lung function after HDM challenges. We measured AHR to methacholine and calculated the dose of methacholine required to induce a resistance of 3 cmH2O.s/mL (ED3; Figure 3B). Herein, both HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT show a trend toward increased ED3 compared to the positive controls. Next, we compared the resistance across all dose‐response curves and found that both HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT were significantly reduced, as evidenced from a right shift of curves and a reduced plateau at higher concentrations (Figure 3C). In addition, while we observed significantly reduced compliance in HDM‐challenged mice, both HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT did not improve lung compliance (Figure 3D).

3.7. HDM and DerP1/2‐SCIT suppress eosinophilic airway inflammation and cytokine levels

Successful SIT is associated with suppression of Th2 cell activity and reduced airway inflammation upon challenges. Therefore, we assessed inflammation and Th2 cytokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). As expected, HDM challenges in positive controls induced a pronounced eosinophilic airway inflammation (Figures S2C and 4A,B). Both HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT resulted in markedly decreased eosinophil numbers in BAL, with a relative eosinophil suppression by both treatments of ~5‐fold compared to controls (Figure 4B). To evaluate the activity of the Th2 cells and ILC2s, we analyzed levels of IL‐5, IL‐10, and amphiregulin in BALF and observed a significantly reduced IL‐5 level only in DerP1/2‐SCIT–treated mice, when compared to positive controls (Figure 4C), while IL‐10 and amphiregulin levels were unaffected by either treatment (Figure S2D,E).

Figure 4.

The eosinophilic and cytokine response after subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) treatment. A, Differential cytospin cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). M: Mononuclear cells, E: eosinophils, N: neutrophils. Absolute numbers are plotted in the box‐and‐whisker plots (min‐max). B, Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) eosinophils, plotted as fold suppression (absolute eosinophils/average PC‐eosinophils; mean ± SEM). C, Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) IL‐5 levels (pg/mL) (mean ± SEM). D, Net levels of IL‐5, IL‐10, and IL‐13 measured in restimulated lung single cell suspensions. Concentrations were calculated as the concentration after restimulation minus control and plotted in the box‐and‐whisker plots (min‐max). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 compared to PC. NC: Negative control, PBS challenged; PC: positive control, HDM challenged; HDM and DerP1/2: different SCIT treatments, HDM challenged

Next, we analyzed allergen‐specific Th cell activity by measuring cytokine release in the supernatant of restimulated lung cell suspensions. Here, we observed a significantly reduced production of IL‐5 (only in HDM‐SCIT) and IL‐13 levels in HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT mice compared to controls (Figure 4D). Interestingly, in both SCIT groups, we also observed an increased IL‐10, indicating the presence of regulatory T cells.

3.8. HDM and DerP1/2‐SCIT suppress type 2 responses

Given the somewhat contrasting results of the type 2 cytokines in BALF and in restimulated cell suspensions, we also analyzed the levels of the signature type 2 inflammatory cytokines in lung tissue of HDM‐treated, DerP1/2‐treated, and sham‐SCIT–treated mice. Here, we find that HDM challenges in sham‐treated mice induced a strong IL‐4, IL‐15, and IL‐13 response compared to negative controls (Figure 5A). SCIT with DerP1/2, but not with HDM, was able to suppress IL‐4 and IL‐5, while IL‐13 was not affected by either treatment. In contrast, we find that HDM‐SCIT and DerP1/2‐SCIT did not induce increased levels of IL‐10 in lung tissue (Figure 5B). We also measured IFN‐γ levels to control for any effect on Th1 cell activity and found no induction in this model.

3.9. DerP1/2‐SCIT suppresses release of the epithelial chemokine CCL20

To test whether SCIT also affected the innate response to allergens, we assessed levels of pro‐inflammatory chemokines and alarmins released by lung structural cells upon HDM exposure.7 Here, we observe that challenges clearly induced release of eotaxin, IL‐33, TARC/CCL17, and MIP3a/CCL20 indicating activation of the innate immune system and structural cells (Figure 5B,C). Interestingly, we observed that only DerP1/2‐SCIT resulted in suppression of CCL20 levels and showed a trend toward suppression of eotaxin, IL‐33, and CCL17 levels in lung tissue. No significant effect of SCIT on IL‐17 was observed (data not shown).

Next, we asked whether the levels of the Der P1 specific neutralizing antibodies after SCIT correlated with a decreased AHR or immunological response after HDM challenges. Here, we found a negative correlation between Der p1‐spIgG1 (post‐SCIT) vs the lung cytokines IL‐4, IL‐5, and CCL20 and BALF IL‐5 levels (Figure 5D,E). In contrast, we did not observe a significant correlation between the Der p1‐spIgG1 levels and the more translational parameters ED3 or the EST.

3.10. DerP1/2‐SCIT dose dependently modifies the allergic immune response

Finally, we asked whether the use of purified DerP1/2 would allow use of a lower dosage of protein for successful treatment. To this end, we used three dosages of 5, 10, and 20 μg of DerP1/2 vaccine complexed to SAINT for improved delivery, and compared the effect of DerP1/2‐SCIT to SAINT‐only control treatment (Figure 6A,B).23 We find that low DerP1/2 dosages do not suppress ESR after challenge. In contrast, the highest dose of the DerP1/2‐SCIT groups did induce significant suppression compared to SAINT‐treated controls (Figure 6C). In addition, the DerP1/2 vaccine dose dependently modified eosinophilic inflammation and AHR (Figure 6D,E). Remarkably, low‐dose DerP1/2 exaggerated eosinophilic inflammation and AHR. In contrast, 20 μg DerP1/2 did show therapeutic effect, albeit limited, in suppressing AHR, while airway eosinophilia was not suppressed. All three doses of DerP1/2 failed to suppress IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐17 levels in lung tissue. Furthermore, only the highest dose of DerP1/2 was able to suppress IL‐33 (Figure 6F).

Overall, while the lowest dose of the DerP1/2 vaccine exaggerated the allergic phenotype, the use of 20 μg was capable of suppressing some of the allergic asthma parameters, such as AHR and lung tissue IL‐33. Taken together, these data indicate that DerP1/2 is able to modify the allergic immune response, with higher levels inducing a suppression of allergic inflammation and achieving an enhanced lung function.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we asked whether purified Der p1 and 2 would have superior activity in DerP1/2‐SCIT compared to HDM extracts. A direct comparison of both treatments clearly indicates that the DerP1/2 vaccine results in marked suppression of type 2 cytokine levels in lung and BALF, and increased Der p1‐spIgG responses. The levels of Der p1 specific IgG1 after SCIT were negatively correlated to levels of IL‐5, IL‐13, and CCL20 after HDM challenge, indicating a protective role for this neutralizing antibody response in our mouse model. Moreover, DerP1/2‐SCIT was uniquely able to prevent the HDM challenge‐induced increase in CCL20/MIP3‐α levels, and a similar trend was observed toward preventing the HDM‐induced CCL17/TARC and eotaxin response in lung tissue. While these immunological parameters argue in favor of DerP1/2‐SCIT, we do not observe differences in the more translational parameters of AHR, EST, and eosinophilia, where both treatments have similar efficacy in suppressing the allergic responses. Hence, we postulate that DerP1/2‐SCIT is at least as effective in suppressing the HDM‐induced adaptive and innate responses as whole body extracts, warranting translational studies to evaluate whether a similar approach is also efficacious in men.

The difference in suppression of type 2 cytokines and induction of neutralizing antibody responses might be the result of the higher protein dose of Der p1 and 2 that is achieved by administration of purified allergens compared to full extract, which contained 28.5 mg Der p1 and 1.8 mg Der p2 per gram dry weight. Of note, we only observe a spIgG response to Der p1 after DerP1/2‐SCIT. The absence of a Der p2‐spIgG response after the Der P1/2‐SCIT could be explained by the use of Der p1 and 2 in a 50:1 molar ratio. Consequently, most of the effects in this model might depend on modulation of the Der p1 specific response. Altering the ratio of Der p1 to Der p2 to also induce a Der p2‐spIgG response might further improve the efficacy of the vaccine. Moreover, addition of Der p23 into the mixture might further increase the value of a vaccine, as, in adults, sensitization to Der p1, 2, and 23 allergens has the highest prevalence, and sensitization to these allergens precedes that of other major Der p allergens, indicating their critical role in HDM allergy.10

Another potential advantage of the use of purified proteins over an extract for SIT is the lack of nonprotein constituents of the extracts, including chitin, beta‐glucans, and endotoxins. These contaminants might activate a pro‐inflammatory innate response upon injection of the vaccine. We observe a reduction in HDM‐induced CCL20 levels and a trend toward reduction in CCL11/eotaxin, CCL17/TARC, and IL‐33 levels in DerP1/2‐SCIT mice, which might reflect a reduced activation status of the innate immune system. In agreement herewith, it has been reported that full extract challenges in allergic asthma patients induced a stronger late allergic response compared to challenges with Der p1 and 2, while early responses were identical, which was attributed to nonprotein constituents of the HDM extract.24

Pro‐inflammatory activation of the antigen‐presenting cell during SCIT might also negatively influence the induction of a tolerogenic T‐cell response.25 However, some studies have reported successful use of TLR agonists as adjuvants for allergen immunotherapy, including monophosphoryl lipid A26 or bacterial DNA rich in CpG motifs,27 indicating that activation of specific PRRs may in fact be beneficial in SIT. Notwithstanding, using biochemically and pharmacologically defined products for SIT will increase quality of the treatment.

Other approaches to develop novel therapeutic allergy vaccines for use in SIT for HDM include the generation of recombinant hypoallergenic combination vaccines of Der p1 and 2, which were shown to have limited IgE reactivity, while retaining its T‐cell epitopes and the ability to induce neutralizing antibody response in experimental models that could block IgE binding.11, 28 The use of these hypoallergenic recombinant vaccines holds the promise of inducing fewer side effects during therapy. Der p1 peptides have also been delivered on virus‐like particles, inducing IgG responses within 4 weeks after a single injection in healthy subjects.29 Both of these approaches involve the use of recombinant hypoallergenic proteins or peptides, while we use purified natural proteins, with high purity and pharmacologically well defined, but retaining the activity to crosslink IgE. Although hypoallergenic proteins are considered to have a better safety profile during treatment, is currently unknown whether hypoallergenic vaccines have a comparable therapeutic efficacy compared to IgE‐activating allergens. Initial studies show that hypoallergenic proteins can induce neutralizing antibodies that inhibit allergen‐mediated cross‐linking of IgE.11, 30 IgE cross‐linking vaccines might have some additional therapeutic efficacy due to so‐called piecemeal degranulation of mast cells and basophils, which is thought to contribute to protection against allergic responses especially during the early phase of treatment due to inactivation or exhaustion of these effector cells.30 Further research will need to establish whether purified natural allergens, that can be produced in relatively high quantities under strictly controlled conditions at relatively low costs and address both effector cell responses, B‐cell and T‐cell activity, or recombinant hypoallergenic or peptide vaccines that require far higher production costs and mainly address the T‐cell response, will be the most optimal treatment for SIT.

We provide evidence that Der p1 and 2 can be used as a pharmacologically well‐defined SIT in the HDM‐sensitized host to suppress allergic responses, with superior activity compared to HDM extract with regard to Th2 cell cytokines as well as the chemokines and alarmins released by the lung structural cells upon HDM exposure. House dust mite (HDM) extract and purified allergens were equally effective in suppressing eosinophilic airway inflammation and AHR. These data warrant clinical studies to explore the safety and efficacy of the use of these purified natural allergens as a novel vaccine for HDM‐induced allergic disease, including rhinitis and allergic asthma.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors LH, NvI, CH, AP, and MHR confirm that there are no conflict of interests to disclose. ACG is stockholder and the chief executive officer at Citeq BV (Groningen, the Netherlands), a company that owns patents on Der p1‐Der p2, and produces and markets similar compounds. BG is stockholder and the mite expert at Citeq BV. TS and SK are both employees of Citeq BV. MCN reports consultancy fees paid by DC4U for scientific advice. In addition, Citeq BV names ACG, MCN, and LH inventors on a patent NL2014882 owned.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the mentioned authors read and approved the manuscript and agreed to the submission of the manuscript to the Journal. LH contributed to the development of the immunotherapy model, conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, editing the figures, and preparation and critical revision of the manuscript. NvI and CH contributed to the acquisition and interpretation of the data. AHP contributed to the acquisition of all in vivo work. NvI, CH, and AHP critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. SK and TS are employees of Citeq BV, contributed to the production of the HDM extracts and the purification of the Der p1 and Der p2, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. BG and ACG are both stockholders at Citeq BV, contributed to the design of the study, production, purification of the Der p1 and Der p2 and HDM extracts, interpretation of the data, and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. MHR contributed to the design of the study, provided excellent detailed information on the SAINT amphiphilic carrier complexed to the allergens, and provided critical revision of the manuscript. MHR approved the final version of the manuscript. MCN contributed to the development of the immunotherapy model, conception and design of the study, critical interpretation of the results, editing the figures, and preparation and critical revision of the manuscript. MCN approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Biobrug program (Project 97). We would like to thank Uilke Brouwer (research technician), Harold G. de Bruin (staff technician), and Susan Nijboer‐Brinksma (research technician). Also, Dr. Ed G. Talman is acknowledged for providing excellent quality SAINT C‐18 (Synvolux therapeutics). Last, we thank the microsurgical team in the animal center (A. Smit‐van Oosten, M. Weij, B. Meijeringh, and A. Zandvoort) for expert assistance at various stages of the project.

Hesse L, van Ieperen N, Habraken C, et al. Subcutaneous immunotherapy with purified Der p1 and 2 suppresses type 2 immunity in a murine asthma model. Allergy. 2018;73:862–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13382

REFERENCES

- 1. Hoffmann HJ, Valovirta E, Pfaar O, et al. Novel approaches and perspectives in allergen immunotherapy. Allergy. 2017;72:1022‐1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Barrier epithelial cells and the control of type 2 immunity. Immunity. 2015;43:29‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akdis CA, Blesken T, Akdis M, Wuthrich B, Blaser K. Role of interleukin 10 in specific immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:98‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matsuoka T, Shamji MH, Durham SR. Allergen immunotherapy and tolerance. Allergol Int. 2013;62:403‐413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wambre E. Effect of allergen‐specific immunotherapy on CD4 + T cells. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:581‐587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hinz D, Seumois G, Gholami AM, et al. Lack of allergy to timothy grass pollen is not a passive phenomenon but associated with the allergen‐specific modulation of immune reactivity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:705‐719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Post S, Nawijn MC, Hackett TL, et al. The composition of house dust mite is critical for mucosal barrier dysfunction and allergic sensitisation. Thorax. 2012;67:488‐495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marth K, Focke‐Tejkl M, Lupinek C, Valenta R, Niederberger V. Allergen peptides, recombinant allergens and hypoallergens for allergen‐specific immunotherapy. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2014;1:91‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tourdot S, Airouche S, Berjont N, et al. Evaluation of therapeutic sublingual vaccines in a murine model of chronic house dust mite allergic airway inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1784‐1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Posa D, Perna S, Resch Y, et al. Evolution and predictive value of IgE responses toward a comprehensive panel of house dust mite allergens during the first 2 decades of life. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;139:541‐549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen KW, Blatt K, Thomas WR, et al. Hypoallergenic der p 1/Der p 2 combination vaccines for immunotherapy of house dust mite allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:435‐443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Valenta R, Ferreira F, Focke‐tejkl M, et al. From allergen genes to allergy vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:211‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pittner G, Vrtala S, Thomas WR, et al. Component‐resolved diagnosis of house‐dust mite allergy with purified natural and recombinant mite allergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:597‐603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vidal‐Quist JC, Ortego F, Castañera P, Hernández‐Crespo P. Quality control of house dust mite extracts by broad‐spectrum profiling of allergen‐related enzymatic activities. Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;72:425‐434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yasueda H, Mita H, Yui Y, Shida T. Isolation and characterization of two allergens from Dermatophagoides farinae. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1986;81:214‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yasueda H, Mita H, Yui Y, Shida T. Comparative analysis of physicochemical and immunochemical properties of the two major allergens from Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and the corresponding allergens from Dermatophagoides farinae. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1989;88:402‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chapman MD, Platts‐Mills TA. Purification and characterization of the major allergen from Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus‐antigen P1. J Immunol. 1980;125:587‐592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halim A, Carlsson MC, Madsen CB, et al. Glycoproteomic analysis of seven major allergenic proteins reveals novel post‐translational modifications. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:191‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hesse L, Nawijn MC. Subcutaneous and sublingual immunotherapy in a mouse model of allergic asthma In: Clausen BE, Laman JD, eds. Inflammation: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2017: 137‐168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shirinbak S, Taher YA, Maazi H, et al. Suppression of Th2‐driven airway inflammation by allergen immunotherapy is independent of B cell and Ig responses in mice. J Immunol. 2010;185:3857‐3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Twisk JWR. Longitudinal data analysis. A comparison between generalized estimating equations and random coefficient analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:769‐776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Custovic A, Soderstrom L, Ahlstedt S, Simpson A, Holt PG. Allergen‐specific IgG antibody levels modify the relationship between allergen‐specific IgE and wheezing in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1480‐1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kowalski PS, Zwiers PJ, Morselt HWM, et al. Anti‐VCAM‐1 SAINT‐O‐Somes enable endothelial‐specific delivery of siRNA and downregulation of inflammatory genes in activated endothelium in vivo. J Control Release. 2014;176:64‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Der Veen MJ, Jansen HM, Aalberse RC, Van Der Zee JS. Der p 1 and Der p 2 induce less severe late asthmatic responses than native Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract after a similar early asthmatic response. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:705‐714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Akdis CA, Akdis M. Advances in allergen immunotherapy : aiming for complete tolerance to allergens. Sci Tranl Med. 2015;7:1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mothes N, Heinzkill M, Drachenberg KJ, et al. Allergen‐specific immunotherapy with a monophosphoryl lipid A‐adjuvanted vaccine: reduced seasonally boosted immunoglobulin E production and inhibition of basophil histamine release by therapy‐induced blocking antibodies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:1198‐1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Creticos PS, Schroeder JT, Hamilton RG, et al. Immunotherapy with a ragweed‐toll‐like receptor 9 agonist vaccine for allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1445‐1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Asturias JA, Ibarrola I, Arilla MC, et al. Engineering of major house dust mite allergens der p 1 and der p 2 for allergen‐specific immunotherapy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:1088‐1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kundig TM, Senti G, Schnetzler G, et al. Der p 1 peptide on virus‐like particles is safe and highly immunogenic in healthy adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1470‐1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akdis CA, Akdis M. Mechanisms of allergen‐specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:18‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials