Abstract

The CRISPR-based technology has revolutionized genome editing in recent years. This technique allows for gene knockout and evaluation of function in cell lines in a manner that is far easier and more accessible than anything previously available. Unfortunately, the ability to extend these studies to in vivo syngeneic murine cell line implantation is limited by an immune response against cells transduced to stably express Cas9. In this study, we demonstrate that a non-integrating lentiviral vector approach can overcome this immune rejection and allow for the growth of transduced cells in an immunocompetent host. This technique enables the establishment of a von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene knockout RENCA cell line in BALB/c mice, generating an improved model of immunocompetent, metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Keywords: immunocompetent mouse model, ccRCC, RENCA, kidney cancer, CRISPR/Cas9, non-integrated lentivirus, immunotherapy

Introduction

Murine models have proved an invaluable tool in studying the molecular contributors to the development and progression of cancer.1 The discovery and utilization of novel genetic tools, such as homologous recombination and small hairpin RNA (shRNA) gene knockdown, have led to a myriad of important discoveries in this field.2 Now the new CRISPR technique is poised to continue in this vein with its own revolution.2 Already this technique has been leveraged in a variety of studies that have led to interesting findings regarding tumor development, metastasis, and treatment susceptibility.3, 4, 5 However, there is an absence of reports of using this technology to produce in vitro gene changes in murine cell lines that can then be implanted into immunocompetent hosts in novel murine models. Perhaps the reason for this absence is due to an immune reaction against the bacterial Cas9 protein, as has been previously demonstrated.6

In contrast to many human cell lines, some murine cell lines are not amenable to highly efficient transfection.7, 8 For this reason, a lentiviral approach has been commonly used to modify these cells in vitro.9, 10, 11 Transduction by lentivirus leads to highly effective gene expression but involves stable integration of the introduced exogenous genes, allowing for a potential immune rejection.12 Studies have shown that integrase-defective lentiviral vectors are capable of producing nonintegrated viral DNA transiently that can support transcription.13 In this study, we produced CRISPR-modified murine cell lines using engineered non-integrating lentiviral (NIL) vectors containing mutated integrase developed by Nightingale et al.14 We go on to show that the murine renal cell carcinoma RENCA cell line produced by the NIL CRISPR vectors grows just as well in the syngeneic BALB/c mice as the wild-type parental cell line, whereas the cell line with stable viral integration either fails to grow or eventually regresses. To date, there is no syngeneic mouse model of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) that is deficient in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene, yet 80%–90% of patients with clear cell RCC, the most common type of RCC accounting for nearly all metastatic cases, have a defect in the VHL pathway.15 Thus, a model that is both immune competent and VHL deficient would greatly improve our ability to perform relevant preclinical studies in RCC. Using this NIL technique, we were able to generate a novel, immunocompetent murine model of metastatic RCC by CRISPR-mediated knockout of VHL.

Results

Using NIL to Generate Clonal Cas9-Modified Cell Lines

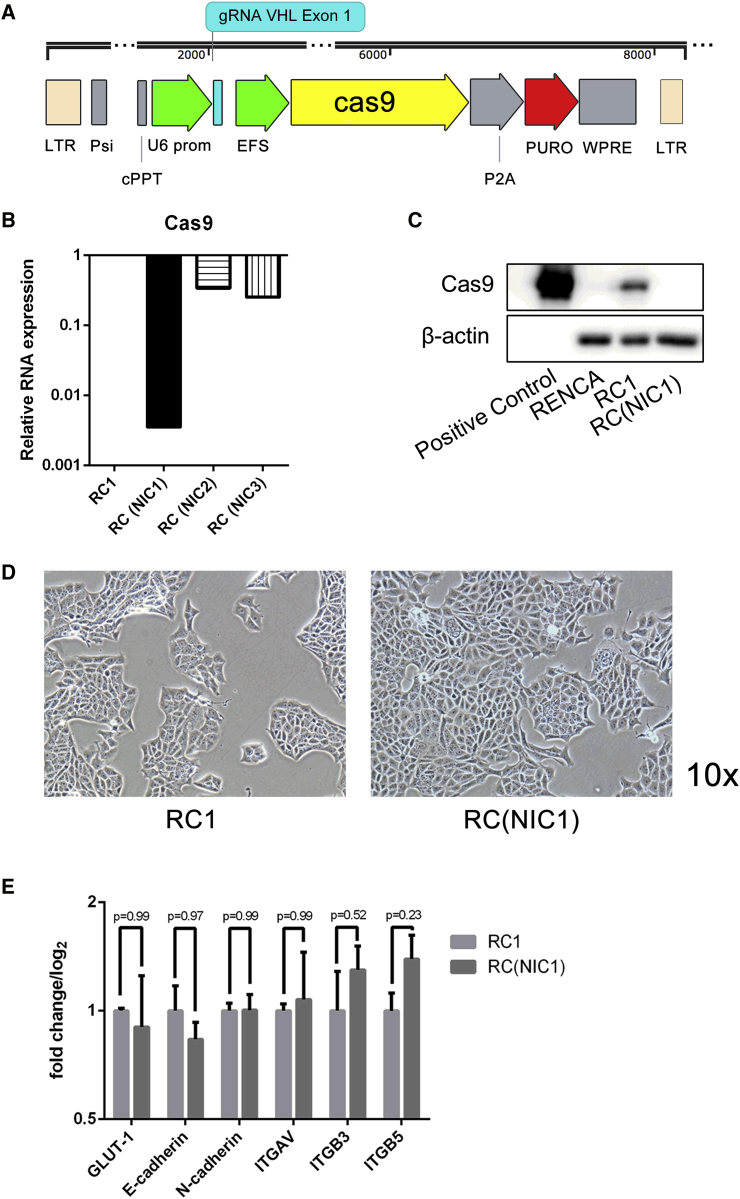

In a recent study, we employed the lentiviral CRISPR-Cas9 method to perform gene editing in several RCC cell lines in an effort to dissect the molecular pathways involved in the oncogenesis of this disease.15 Interestingly, we showed that knocking out the VHL tumor suppressor gene in the RCC cell lines led to epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and increased metastasis in vivo, specifically in the murine RENCA model. However, when we attempted to implant the lentiCRISPR-modified RENCA cell lines into their syngeneic immunocompetent BALB/c hosts, the tumors failed to grow.16 In multiple studies, we would observe initial tumor growth in the first week followed by subsequent tumor regression and complete disappearance by 4 weeks (data not shown). The initial VHL-null RENCA cell line (RVN) and its control (RC, using irrelevant luciferase-targeted guide RNA) generated with integrating Cas9 were mixed cell populations produced after transduction with high virus-to-cell ratio of the respective lentiCRISPR. A schematic representation of the lentiCRISPR vector is shown in Figure 1A. To better pinpoint the problem of non-engraftment, we selected individual clonal populations from the initial lentiCRISPR-derived RC and RVN mixed populations and designated them as RC1 and RVN1. Attempts to engraft these clonally selected lines into BALB/c mice also failed (data not shown). Given reports of a cell-mediated immune response to the Cas9 protein,6 we thought it possible to avoid this immune-mediated rejection through transducing the cells with NIL. We generated the control lentiCRISPR vectors using the packaging constructs with an integrase mutation.14 Although the viral integrase function is crippled, a low level of integration is still possible. For this reason, we screened several of the clonally selected RC lines for the lowest Cas9 expression (Figure 1B). The NIL-transduced RC clonal lines are designated as RC(NIC1), RC(NIC2), and RC(NIC3). Among these three NIL-derived clone (NIC) lines, RC(NIC1) exhibited lowest Cas9 expression at a level that is nearly three orders of magnitude lower than RC1. Western blot further confirmed Cas9 protein expression is present in RC1, but not in the RC(NIC1) cell line (Figure 1C). Both RC1 and RC(NIC1) cells displayed the cobblestone epithelial morphology, with no discernable cell morphologic differences between them (Figure 1D). Furthermore, we analyzed the mRNA level of several key genes, such as GLUT-1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and integrins ITGAV, ITGB3, and ITGB5. There is no significant difference in the expression of these genes in the two cell lines (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Generation of Cas9-Transduced, Non-integrating Cells

(A) Schematic representation of lentiCRISPR with gRNA targeting murine VHL downstream of a U6 promoter. Cells were derived by infection with this lentivirus packaged with either wild-type or mutated integrase. Other elements of the virus include tandem long terminal repeat sequences (LTR), Psi signal, central polypurine tract (cPPT), EFS promoter, Cas9 sequence, P2A element, puromycin resistance gene (Puro), and WPRE. (B) Cas9 gene expression in RC clonal lines were assessed by RT-PCR. The expression of NIL-generated clones RC(NIC1), RC(NIC2), and RC(NIC3) relative to the integrated lentiCRISPR-generated line, RC1, is shown. The Cas9 expression in RC1 is normalized to 1. (C) Western blot for Cas9 in RENCA, RC1, and RC(NIC1) cells. Cas9 protein is shown for positive control in the left lane. (D) Light microscopic images of RC1 and RC(NIC1) cells at 10× magnification. (E) qRT-PCR analysis of genes in RC1 and RC(NIC1) cells.

NIC Cells Grow in an Immunocompetent BALB/c Host

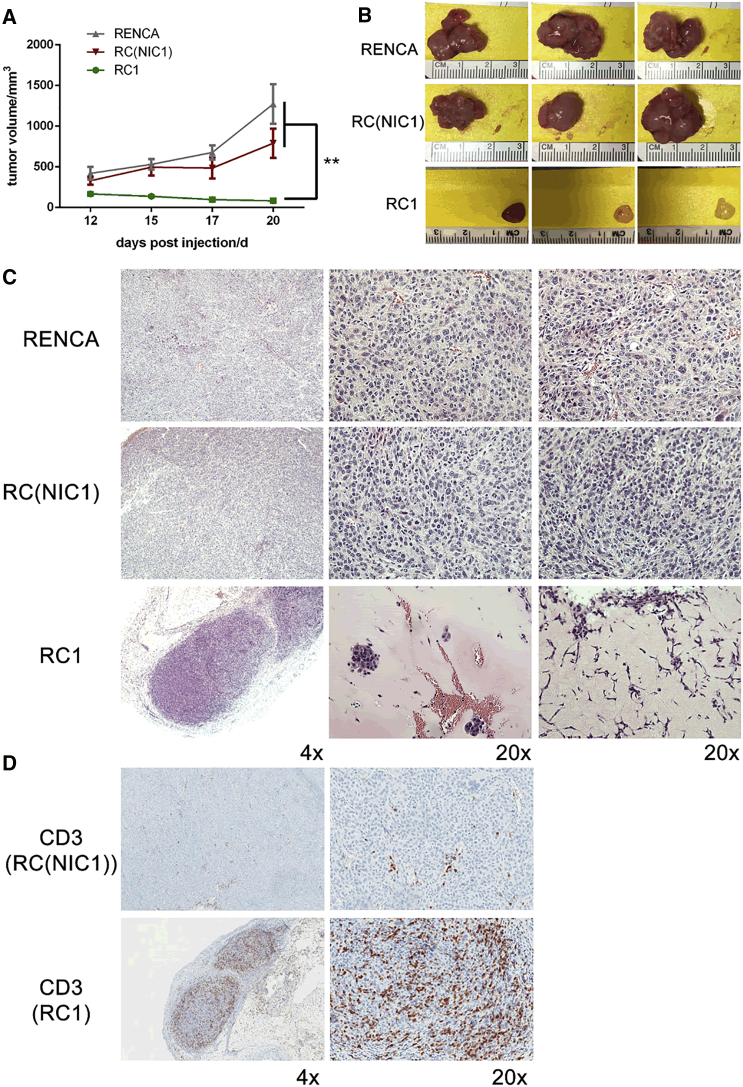

Next, we compared the ability of RC1 and RC(NIC1) with parental RENCA cells to establish subcutaneous tumors in syngeneic BALB/c mice. As expected, the implanted parental RENCA cells grew robustly, reaching tumor size of 1.5 cm in diameter in about 3 weeks (Figure 2). In contrast, the clonally selected RC1 cell line with stable Cas9 expression showed impaired initial growth followed by regression (Figure 2A), as we have observed in our previous studies. Interestingly, the RC(NIC1) line grew at a rate comparable to the parental RENCA line (Figure 2A). Gross examination of harvested tumor revealed healthy, well-vascularized tumors established with the RENCA and RC(NIC1) cells. In contrast, the three small RC1 tumors are pale and fibrotic in appearance, and the tumor in the fourth animal completely regressed (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Using Non-integrating Lentivirus Allows for Growth of lentiCRISPR-Modified Cells in an Immunocompetent BALB/c Host

(A) Growth curves for subcutaneous tumors implanted with RENCA, RC(NIC1), and RC1 cells over 20 days in BALB/c mice. n = 4 per group. (B) Images of gross tumors from three representative animals in each group are shown. The RC1 tumor in the fourth animal completely regressed. (C) Representative H&E images of tumors from each of three groups in both 4× and 20× magnification are shown. (D) Representative images of immunohistochemistry staining of CD3 in RC(NIC1) and RC1 tumors (**p < 0.01).

An Immune Reaction Mediates Rejection of Cas9-Expressing Cells

Further histological analyses revealed by H&E staining showed RENCA and RC(NIC1) tumors contain healthy mitotic tumor cells with large nuclei (Figure 2C). In contrast, the residual RC1 tumors contained large regions of non-cellular matrix surrounding small cellular islands. In one of the RC1 tumors with the most abundant tumor cells, a prominent infiltration of immune cells and lymphocytes with irregular-shaped or small dense nuclei can be seen in the tumor (Figure 2C). Immunohistochemical staining with CD3 revealed a dramatically increased lymphocytic infiltration in the RC1 tumor that was absent in the RC(NIC1) tumor (Figure 2D). To further support the presence of an immune rejection against the RC1 tumors, we utilized an ELISA to test for immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) targeting Cas9. As suspected, expression of Cas9-targeted IgG1 was elevated in serum from mice harboring RC1 tumor, but not in RENCA or RC(NIC1) tumor bearing mice (Figure S1). Interestingly, immunogenic response against different foreign proteins in mice is not uniform. For instance, no retardation of engraftment of RENCA-FL cells was observed in BALB/c mice (Figure S2; see also Figure 4). This cell line was generated by transducing with a conventional integrating lentivirus expressing firefly luciferase (FL). Taken all together, our findings suggest that this immune-mediated rejection is likely directed at the stably expressed Cas9 protein in our lentiCRISPR-modified RENCA cell lines.

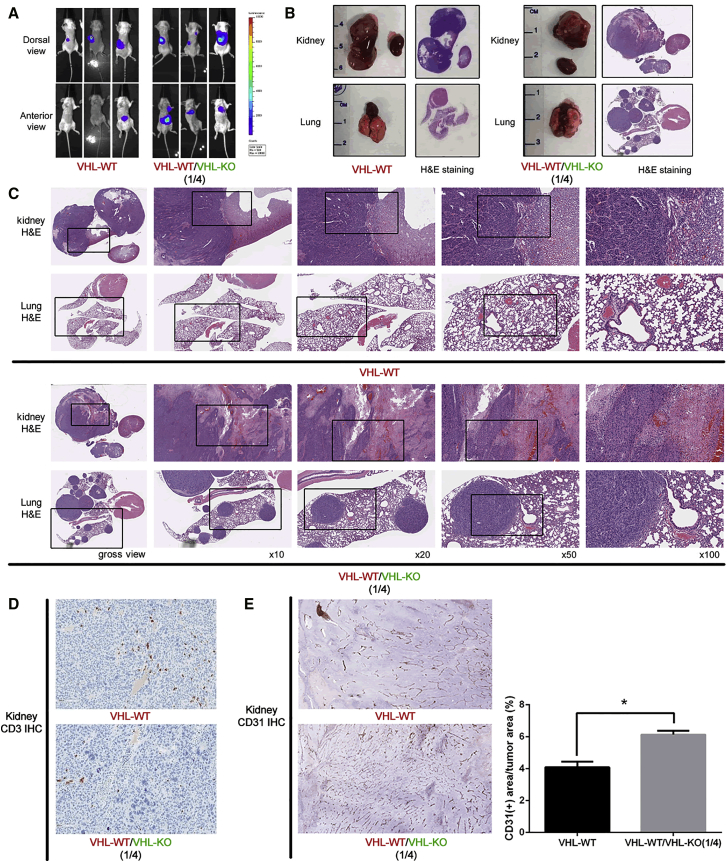

Figure 4.

A VHL-Knockout, Immunocompetent, Metastatic RCC Model

Intrarenal tumors were established in BALB/c mice with 106VHL-WT cells or a 1:4 ratio of VHL-WT and VHL-KO cells. (A) BLI was used to detect firefly-luciferase-expressing tumors in vivo. Three representative tumor-bearing mice in each group at the endpoint 6 weeks after tumor implantation were shown. (B) Gross images and unmagnified H&E stain of harvested organs, including the primary kidney tumor and contralateral normal kidney, as well as lung and heart from both groups, were shown. (C) Higher magnification H&E stains of primary tumors and lungs were shown. (D) Immunohistochemical stain of CD3 in the primary tumor to identify infiltrating T lymphocytes in both groups. (E) Immunohistochemistry staining of CD31 depicting the blood vessels within the primary tumor were performed. Whole-section scanning was performed by Applied Imaging Leica Aperio Versa high-throughput scanning system, and quantification was performed by Definiens’ Tissue Studio at TPCL of UCLA. The angiogenesis was evaluated by CD31 positivity area within tumor region and denoted by % as shown in the right. (*p < 0.05)

Using the NIL Approach to Generate a VHL Knockout Immunocompetent Metastatic RCC Model

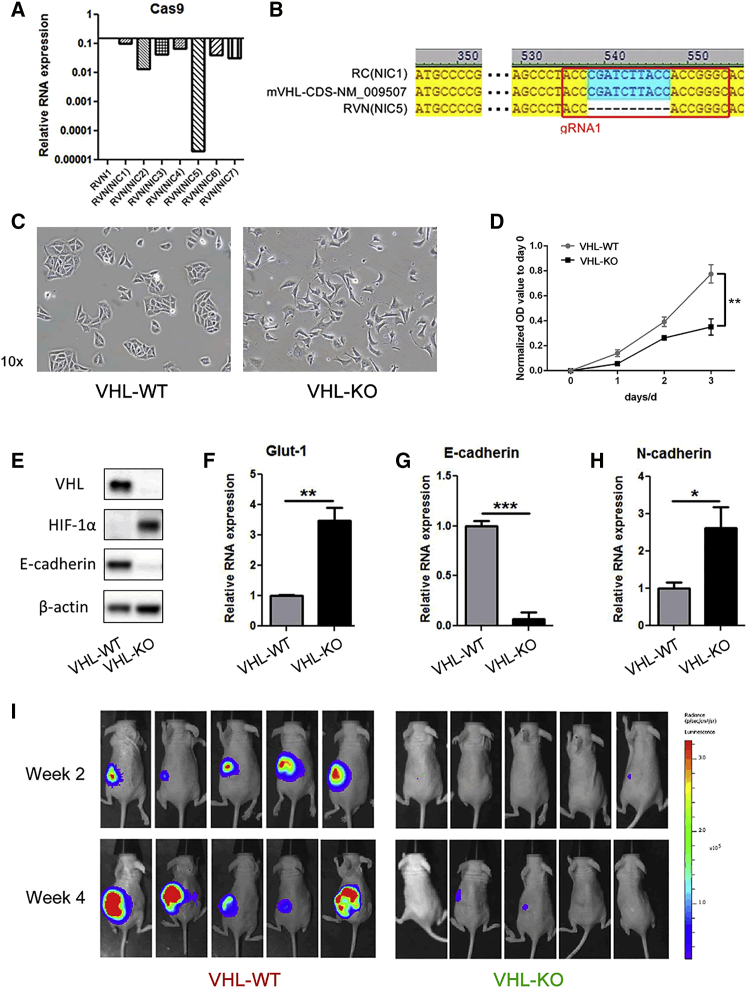

Because the transiently expressing NIL appeared to overcome the immunogenicity against Cas9, we sought to verify whether the NIL CRISPR vector could indeed achieve the designed targeted gene disruption. We have recently reported the knockout of the VHL tumor suppressor gene in the RENCA cell line by lentiCRISPR-promoted EMT and dramatically increased metastatic behavior in vivo in immunodeficient mice.15 We regenerated the VHL-knockout RENCA cell line with the NIL CRISPR vector and clonally selected seven lines, designated as RVN(NIC1) to RVN(NIC7). The level of Cas9 expression was assessed in these clonal lines (Figure 3A). We selected the RVN(NIC5) line for further analyses based on its very low level of Cas9 expression, which is less than 0.0001 of the integrating lentiCRISPR-generated RVN1. DNA sequencing revealed a 10-base-pair deletion within the region targeted by our guide RNA (gRNA) in RVN(NIC5) (Figure 3B). Please note: since we have selected the optimal NIC line to study further on, we will refer to the RENCA control, RC(NIC1) clonal line as VHL-WT and the RVN(NIC5) clonal line as VHL-KO. This will simplify the nomenclature with the genomic designation of each line.

Figure 3.

Generation of Clonally Selected, Non-integrating, VHL Knockout RENCA Cells

(A) Cas9 gene expression levels in seven clonal, non-integrating RVN lines (RVN(NIC1–7)) were assessed by RT-PCR. The expression level in an RC1 integrated lentiCRISPR generated line is set at 1. (B) The DNA sequences in the mVHL coding region from RC(NIC1) and RVN(NIC5) are shown with the reference sequence. A 10-base-pair deletion within the region targeted by our VHL gRNA was found in RVN(NIC5) cells, but not in RC(NIC1). Please note: from here on, the RC(NIC1) clonal line will be designated as VHL-WT and the RVN(NIC5) clonal line as VHL-KO. (C) Representative images of VHL-WT and VHL-KO cells under light microscopy with 10× fields. (D) Cell proliferation assay and (E) western blot for VHL, HIF-1α, E-cadherin, and β-actin in VHL-WT and VHL-KO cells. Gene expression was assessed by RT-PCR for (F) Glut-1, (G) E-cadherin, and (H) N-cadherin (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (I) Either VHL-WT or VHL-KO cells were implanted into the subcapsular space of the left kidney in NU/J nude female 5-week-old mice. VHL-WT tumors grew well, while VHL-KO tumors grew poorly, as monitored by firefly-luciferase-based in vivo bioluminescence imaging. No lung metastasis was seen in both tumor groups.

Next, we analyzed the functional consequences of the VHL gene deletion. The VHL-KO line displayed a mesenchymal cell morphology, while the appearance of VHL-WT control line is consistent with an epithelial morphology (Figure 3C). The in vitro growth rate of VHL-KO line was significantly lower than VHL-WT (Figure 3D). Western blot showed loss of VHL expression, HIF-1α upregulation and E-cadherin downregulation in the VHL-KO cells (Figure 3E). Expression analyses for Glut-1, E-cadherin and N-cadherin were also consistent with expectations for the loss of VHL gene (Figures 3F–3H). These EMT changes in vitro are the same as we have reported for the non-clonal RVN line.15 These findings further support that the EMT changes are a consequence of loss of VHL gene function and not related to the use of conventional lentivirus or NIL. But RVN renal tumors also metastasized rampantly to lungs compared to RC tumors in immune-deficient mice.15 Hence, we asked whether the intrarenal tumors of clonal VHL-KO cells will display metastatic behavior in BALB/c mice similar to RVN tumors. Interestingly, when the VHL-KO cells were implanted intrarenally, the primary tumor grew very poorly compared to VHL-WT cells with no increase in lung metastasis, as observed by FL-based bioluminescence imaging (BLI) used to track the in vivo growth and metastasis of tumors (Figure 3I). Likewise, clonally selected RVN1 generated with integration competent lentiCRISPR also grew poorly in immunodeficient mice (data not shown). These findings are consistent with the decreased proliferation rate of the mesenchymal VHL-deleted cells we observed here and previously.15

Next, we decided to assess the metastatic potential of our VHL-deleted cells by recreating the mixed cell populations of the original RVN cell line. Estimating 80% of the RVN cells possessed the VHL gene deletion, we establish renal tumors with a mixture of VHL-KO and VHL-WT cells at a ratio of 4:1, referred to herein as the VHL-KO mixed tumor. Orthotopic renal tumors were established with either VHL-WT cells only or the 4:1 mixed VHK-KO:VHL-WT cells, totaling 1 × 106 cells per tumor. Primary tumors from both groups grew robustly over a 6-week duration (Figure 4A). Remarkably, all BALB/c mice bearing the VHL-KO mixed tumors (three out of three animals) developed fulminant lung metastasis, while none of control VHL-WT tumors developed metastases. The metastatic progression was observed by BLI, gross pathology, and histopathological analyses (Figures 3I, 4A, and 4B). H&E stain revealed large primary tumors grew in the kidney from both VHL-WT cells and the VHL-KO mixed cells (Figure 4C). Numerous and large lung metastatic lesions developed only in mice bearing VHL-KO mixed tumors, but not in the VHL-WT tumor group (Figure 4C). Consistent with findings from our subcutaneous tumors (Figure 3D), VHL-WT and VHL-KO mixed kidney tumors or their lung metastatic lesions do not induce a significant infiltration of CD3 cells, confirming a lack of an immune response against tumor cells generated using the NIL method (Figure 4D). Interestingly, VHL-KO mixed tumors also exhibited increased vascular density, assessed by CD31 stain, compared to the VHL-WT tumors (Figure 4E).

Despite multiple attempts, we were unable to establish tumors in syngeneic immunocompetent mice with clonally selected lentiCRISPR-modified cell lines. We surmised that the stably expressed Cas9 could be promoting the immune-mediated rejection in the mice. Our findings show that the use of NIL vectors can successfully perform the gene-editing task and can also circumvent this immune-mediated rejection. This NIL approach enables the successful establishment of a VHL-gene-deleted metastatic RCC model in immunocompetent animals.

Discussion

Herein, we describe the use of NIL, also known as the integrase-deficient lentiviral vector,17 to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 system to knockout the VHL gene in the murine RENCA RCC cell line. As reported by Ortinski et al.,17 NIL is comparable to traditional integration competent lentivirus in regard to vector production capability as well as efficiency of Cas9-mediated gene knockout. Despite the widespread use of lentiCRISPR in genetic modification of cell lines, there is a paucity of reports describing implantable Cas9-modified immunocompetent murine models. We deduced that this could be due to an immune reaction against the stably expressed Cas9 protein, which has been reported.6 However, we are unaware of previous reports that demonstrate tumor regression or lack of growth in an immunocompetent host. In this study, we showed that the NIL CRISPR system that substitutes one plasmid in the workflow of gene transduction enables the development of non-integrated clones capable of being implanted into immunocompetent mice.

Our VHL knockout, immunocompetent RENCA model improves upon the original RENCA model by making it more clinically applicable in a number of ways. As many as 80%–90% of clinical clear-cell RCC have disruption of the VHL gene, either through genetic mutations, deletions, or epigenetic silencing.18 Interestingly, the VHL-deleted RVN line is much more aggressive and metastatic than the parental RENCA model.19, 20, 21 But the RVN line is a mixed non-clonal line. Upon further characterization, we found that pure clone of VHL-deleted lines are slow growing and non-metastatic in vivo. Furthermore, as we showed here, a mixture of pure clone of VHL-KO and VHL-WT cells (derived from NIL CRISPR vectors) are highly metastatic compared to tumors developed from VHL-WT cells only. These findings indicate that the VHL-KO and VHL-WT cells are acting in a cooperative manner to produce the heightened metastatic behavior. We are actively investigating the cross-talk between these two cell populations and the detailed mechanism of metastasis. Several important studies have demonstrated a role for cross-talk between heterogeneous tumor cell populations in the development of metastases.22, 23 In particular, a recent study by Neelakantan et al.23 reported that interactions between EMT and non-EMT cells induced metastasis in breast cancer models. Our chimeric VHL-KO and VHL-WT clear cell RCC here will also help to shed light on the important issue of tumor heterogeneity in cancer progression.

This study presents a significant contribution to the field via our new, metastatic clear cell RCC model that can be studied in an immunocompetent mouse. This model is particularly relevant given the current increased interest in immunotherapy. Interleukin-2 treatment has long been an approved immunotherapy modality for the treatment of RCC, and recent successes with immune checkpoint inhibitors have re-invigorated interest in immunotherapy research for this cancer.24, 25 With the current lack of success using transgenic approaches to generate a metastatic, VHL-deficient, immunocompetent RCC model,19, 20, 21 our CRISPR-modified immunocompetent model presented herein is a valuable tool for assessing the immune contributions to RCC metastasis and investigating potential immunotherapies in murine studies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Generation of Non-integrated Cas9-Modified Clonal Cell Lines

Cell lines were generated and maintained using techniques as previously described.15 The NIL was created using packaging plasmid pCMVΔR(int-)8-2 (kind gift from Dr. Noriyuki Kasahara).14 Cells were transduced as previously described,17 then selected with puromycin (2μg/mL) from 48 to 96 hr following transduction. Cells were expanded and underwent clonal selection as previously described.15 Details on the specific gRNA and its target for each clonal cell line are provided in Table 1. Cas9 expression was assessed by RT-PCR and western blot using CRISPR/Cas9 monoclonal antibody (EpiGentek A-9000-050). Cas9 protein served as a positive control (PNA Bio CP01). Expression of VHL was validated by western blot as previously described.

Table 1.

Cell Line Information

| Cell Line | IentiCRISPR Plasmid | gRNA Sequence (5′–3′ | Original Cell Line |

|---|---|---|---|

| RC1 | Rluc 2 | 5′-CACCGGATGATAACTGGTCCGCAG-3′ | RENCA |

| RVN1 | mVHL 1 | 5′-CACCGCCCGGTGGTAAGATCGGGT-3′ | RENCA |

| RC(NIC1–3) | RLuc 2 | 5′-CACCGGATGATAACTGGTCCGCAG-3′ | RENCA-FL |

| RVN(NIC1–9) | mVHL 1 | 5′-CACCGCCCGGTGGTAAGATCGGGT-3′ | RENCA-FL |

LentiCRISPR plasmids, gRNA sequences, and parental cell lines for the clonal cell lines generated for our studies. Rluc 2, the plasmid containing gRNA sequences targeting renilla luciferase; mVHL, the plasmid containing gRNA sequences targeting murine VHL; RENCA-FL, the cell line contains sequences encoding firefly luciferase.

Subcutaneous and Orthotopic Tumor Study

All animal experiments were approved by the UCLA IACUC and conformed to all local and national animal care guidelines and regulations. Female 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratory) were used for tumor implantation. For subcutaneous tumors, mice were implanted with 1 × 106 RENCA, RC(NIC1), RC1, or RENCA-FL cells under the right flank. Tumor measurements were made by caliper to assess for growth. Mice we sacrificed 20 days following implantation. Peripheral blood was collected at endpoint through eye bleeding, and serum was collected for subsequent ELISA assay. Tumors were processed as previously described.17

For orthotopic intrarenal tumors, mice were placed in the prone position and an incision was made on the left flank. The left kidney was partially exteriorized. A Hamilton syringe (28G) was used to inject either 1 × 106 RC(NIC1) cells or a mixture of 8 × 105 RVN(NIC5) cells and 2 × 105 RC(NIC1) cells in 10 μL of Matrigel (Corning 354234) diluted with pre-cooled PBS in a 1:1 ratio under the kidney capsule. Mice were euthanized with isoflurane inhalation followed with cervical dislocation after 6 weeks. All tumor sectioning and H&E staining was done by the Translational Pathology Core Laboratory (TPCL) at University of California, Los Angeles.

Western Blot and Immunohistochemistry Staining

Western blotting was performed as previously described.15 After 3% paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation overnight and 50% ethanol preservation, tissues were embedded in paraffin wax and cut at 4 μm thickness. For VHL stain, tumor sections were incubated with VHL (sc-5575, 1:200, Santa Cruz). Histological images were either taken by the Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope or scanned by UCLA TPCL.

Immunohistochemistry staining for CD3 was performed on a Bond III autostainer (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) using the Bond Polymer Refine Detection Kit (DS9800; Leica Biosystems). Antigen retrieval was performed on the Bond III using Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 1 (Citrate; pH 6.0) for 30 min. Slides were incubated at room temperature with rabbit monoclonal anti-CD3 antibody (ab16669; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; clone SP7) (1:150) diluted in Bond Primary Antibody Diluent (AR9352; Leica Biosystems) for 30 min. Slides were subsequently incubated with the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for 10 min. Staining was visualized by incubating the slides with the chromogen 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) for 5 min, and the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. Finally, slides were dehydrated in graded ethanol and xylene and coverslipped. Slides were digitized using the Scanscope XT (Aperio Technologies, Visa, CA).

ELISA

ELISA for expression of Cas9-specific IgG1 was performed as previously described.6 Accordingly, 96-well Nunc Maxisorp Plates (Thermo Scientific, cat. #44-2404-21) were coated with SpCas9 protein (PNA Bio, cat. #CP01) at 0.5 μg/well with 1× coating solution concentrate (KPL, cat. #50-84-00) at 4°C. Then on day 2, plates were washed with 1× wash solution concentrate (KPL, cat. #50-63-00) and blocked with 1% BSA blocking/Diluent Solution (KPL, cat. #5140-0006) at 25°C for 1 hr. Mouse sera diluted by 1% BSA diluent solution (KPL, cat. #5140-0006) at the ratio of 1:1,000 were applied to the coated plate. Mouse monoclonal anti-SpCas9 (Epigentek, cat. #A-9000-010) were added to plot the standard curve. After rinse, HRP-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Santa Cruz, 1:5,000) were applied at 25°C for 1 hr. Then 1× 2,2'-azinobis [3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid]-diammonium salt (ABTS) ELISA HRP Substrate (KPL, cat. #5120-0032) were added and examined with Synergy HT microplate reader (BioTek) at 410 nm for further analysis.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between groups were analyzed by Student’s t test.

Author Contributions

J.H. and S. Schokpur conceived the concept, designed and performed the experiments, collected and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. K.H. helped to design the experiments. M.A., A.C.S., J.N., S. Signoretti, and P.K. performed experiments and collected data for the manuscript. S. Signoretti, R.S.B., B.S.K., and H.X. contributed data and to the design of the study and helped revise the manuscript. L.W. contributed to the concept and the design of the study and the preparation and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

S. Schokrpur was supported by the UCLA/Caltech Medical Scientist Training Program (T32GM008042) and a UCLA Tumour Immunology Training grant (5T32CA009120). A.C.S. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of Tumour Immunology Training grant (5T32CA009120) and Virology and Gene Therapy (5T32AI060567). This project is supported by funds provided by the Cancer Research Coordinating Committee, NIH/NCI (R21 CA216770), and NIH (UL1TR001881) to L.W. We would also like to thank the Clinical and Translational Science Institute for access to common equipment that was used for these studies. We also thank the UCLA Translational Pathology Core Laboratory for preparation of tumor samples.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes three figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2018.02.009.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Cheon D.J., Orsulic S. Mouse models of cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2011;6:95–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.3.121806.154244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt R.J., Chen S., Zhou Y., Yim M.J., Swiech L., Kempton H.R., Dahlman J.E., Parnas O., Eisenhaure T.M., Jovanovic M. CRISPR-Cas9 knockin mice for genome editing and cancer modeling. Cell. 2014;159:440–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue W., Chen S., Yin H., Tammela T., Papagiannakopoulos T., Joshi N.S., Cai W., Yang G., Bronson R., Crowley D.G. CRISPR-mediated direct mutation of cancer genes in the mouse liver. Nature. 2014;514:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S., Sanjana N.E., Zheng K., Shalem O., Lee K., Shi X., Scott D.A., Song J., Pan J.Q., Weissleder R. Genome-wide CRISPR screen in a mouse model of tumor growth and metastasis. Cell. 2015;160:1246–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sánchez-Rivera F.J., Papagiannakopoulos T., Romero R., Tammela T., Bauer M.R., Bhutkar A., Joshi N.S., Subbaraj L., Bronson R.T., Xue W., Jacks T. Rapid modelling of cooperating genetic events in cancer through somatic genome editing. Nature. 2014;516:428–431. doi: 10.1038/nature13906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D., Mou H., Li S., Li Y., Hough S., Tran K., Li J., Yin H., Anderson D.G., Sontheimer E.J. Adenovirus-mediated somatic genome editing of Pten by CRISPR/Cas9 in mouse liver in spite of Cas9-specific immune responses. Hum. Gene Ther. 2015;26:432–442. doi: 10.1089/hum.2015.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss J.M., Shivakumar R., Feller S., Li L.H., Hanson A., Fogler W.E., Fratantoni J.C., Liu L.N. Rapid, in vivo, evaluation of antiangiogenic and antineoplastic gene products by nonviral transfection of tumor cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:346–353. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okazaki H., Matsunaga N., Fujioka T., Okazaki F., Akagawa Y., Tsurudome Y., Ono M., Kuwano M., Koyanagi S., Ohdo S. Circadian regulation of mTOR by the ubiquitin pathway in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:543–551. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kay M.A., Glorioso J.C., Naldini L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat. Med. 2001;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baratchart E., Benzekry S., Bikfalvi A., Colin T., Cooley L.S., Pineau R., Ribot E.J., Saut O., Souleyreau W. Computational modelling of metastasis development in renal cell carcinoma. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015;11:e1004626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundqvist A., Yokoyama H., Smith A., Berg M., Childs R. Bortezomib treatment and regulatory T-cell depletion enhance the antitumor effects of adoptively infused NK cells. Blood. 2009;113:6120–6127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naldini L., Blömer U., Gage F.H., Trono D., Verma I.M. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:11382–11388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Philippe S., Sarkis C., Barkats M., Mammeri H., Ladroue C., Petit C., Mallet J., Serguera C. Lentiviral vectors with a defective integrase allow efficient and sustained transgene expression in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17684–17689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606197103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nightingale S.J., Hollis R.P., Pepper K.A., Petersen D., Yu X.J., Yang C., Bahner I., Kohn D.B. Transient gene expression by nonintegrating lentiviral vectors. Mol Ther. 2006;13:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schokrpur S., Hu J., Moughon D.L., Liu P., Lin L.C., Hermann K., Mangul S., Guan W., Pellegrini M., Xu H., Wu L. CRISPR-mediated VHL knockout generates an improved model for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29032. doi: 10.1038/srep29032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalem O., Sanjana N.E., Hartenian E., Shi X., Scott D.A., Mikkelson T., Heckl D., Ebert B.L., Root D.E., Doench J.G., Zhang F. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1247005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ortinski P.I., O’Donovan B., Dong X., Kantor B. Integrase-deficient lentiviral vector as an all-in-one platform for highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2017;5:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore L.E., Nickerson M.L., Brennan P., Toro J.R., Jaeger E., Rinsky J., Han S.S., Zaridze D., Matveev V., Janout V. Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) inactivation in sporadic clear cell renal cancer: associations with germline VHL polymorphisms and etiologic risk factors. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albers J., Rajski M., Schönenberger D., Harlander S., Schraml P., von Teichman A., Georgiev S., Wild P.J., Moch H., Krek W., Frew I.J. Combined mutation of Vhl and Trp53 causes renal cysts and tumours in mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013;5:949–964. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pritchett T.L., Bader H.L., Henderson J., Hsu T. Conditional inactivation of the mouse von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene results in wide-spread hyperplastic, inflammatory and fibrotic lesions in the kidney. Oncogene. 2015;34:2631–2639. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rankin E.B., Tomaszewski J.E., Haase V.H. Renal cyst development in mice with conditional inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2576–2583. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calbo J., van Montfort E., Proost N., van Drunen E., Beverloo H.B., Meuwissen R., Berns A. A functional role for tumor cell heterogeneity in a mouse model of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neelakantan D., Zhou H., Oliphant M.U.J., Zhang X., Simon L.M., Henke D.M., Shaw C.A., Wu M.F., Hilsenbeck S.G., White L.D. EMT cells increase breast cancer metastasis via paracrine GLI activation in neighbouring tumour cells. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15773. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klapper J.A., Downey S.G., Smith F.O., Yang J.C., Hughes M.S., Kammula U.S., Sherry R.M., Royal R.E., Steinberg S.M., Rosenberg S. High-dose interleukin-2 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma : a retrospective analysis of response and survival in patients treated in the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute between 1986 and 2006. Cancer. 2008;113:293–301. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motzer R.J., Escudier B., McDermott D.F., George S., Hammers H.J., Srinivas S., Tykodi S.S., Sosman J.A., Procopio G., Plimack E.R., CheckMate 025 Investigators Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:1803–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.