Abstract

Candida albicans is the most common fungal pathogen causing serious diseases, while there are only a paucity of antifungal drugs. Therefore, the present study was performed to investigate the antifungal effects of saponin extract from rhizomes of Dioscorea panthaica Prain et Burk (Huangshanyao Saponin extract, HSE) against C. albicans. HSE inhibits the planktonic growth and biofilm formation and development of C. albicans. 16–64 μg/mL of HSE could inhibit adhesion to polystyrene surfaces, transition from yeast to filamentous growth, and production of secreted phospholipase and could also induce endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and disrupt cell membrane in planktonic cells. Inhibitory activities against extracellular exopolysaccharide (EPS) production and ROS production in preformed biofilms could be inhibited by 64–256 μg/mL of HSE. Cytotoxicity against human Chang's liver cells is low, with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of about 256 μg/mL. In sum, our study suggested that HSE might be used as a potential antifungal therapeutic against C. albicans.

1. Introduction

Candida albicans is the most common pathogenic fungus in human and could cause a series of skin and superficial mucosal tissue infections, including oral thrush and vaginitis, as well as the lethal invasive systemic candidiasis [1]. Recent years have witnessed the increase in the morbidity and mortality of C. albicans infections, due to the increased use of immune-suppression therapies (resulting from cancer therapies and organ transplantation), the rise in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients, and the emergence of drug resistance [2, 3]. Among the nosocomial bloodstream infections, C. albicans is the fourth most common pathogenic agent [4].

Among the many virulence factors, the capacity of C. albicans to switch from yeast form to hyphal form and to form biofilms on abiotic and biotic surfaces plays a critical role in the pathogenesis [5, 6]. The hyphae of C. albicans could secrete Candidalysin which could damage the epithelial cells and facilitate the survival in and the escape from the macrophages [7, 8]. C. albicans biofilms are complex structures consisted of different types of cells (yeast, hyphal, and pseudo-hyphal forms) encased by the extracellular exopolysaccharide (EPS) generated by the cells within biofilms [9]. The cells in biofilm are much more resistant to antifungal therapies compared to their planktonic counterparts [9]. The biofilm growth is responsible for the majority of C. albicans infections, especially those associated with medical devices such as catheters, pacemakers, dentures, and prosthetic joints [9, 10]. This fungal pathogen causes a large burden on social economy and public health, while there is a dearth of antifungal drugs. The development of drug resistance is making this worse. Therefore, developing novel antifungal agents, especially those effective against biofilm, is a pressing mission.

Natural products have been considered as a huge reservoir for developing new antifungal drugs [11, 12]. Huangshanyao (Chinese name) saponin extract (HSE) is the saponin extract from rhizomes of Dioscorea panthaica Prain et Burk, a traditional medicinal herb that is grown in Southwest part of China such as Yunnan, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Hunan and could be employed to treat bone injuries, hypertension, and gastric disorders [13, 14]. Belonging to Dioscoreaceae family, Huangshanyao is a perennial herbaceous twining vine. This herb is an endemic plant in China and the dried rhizomes are employed for medicinal use. Other plants under the same Dioscoreae genus, such as Dioscoreae nipponica, Dioscoreae hypoglauca, Dioscoreae spongiosa, and Dioscoreae opposite, have also been used as medicinal herbs [15]. There is also documentation about the protecting effects of this herb on cardiovascular disorders and this herb is the major and essential component of the marketed drug Diao Xin Xue Kang which has been approved by China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) for ameliorating the symptoms of cardiovascular diseases [13]. The saponin extract (rich in over 30 steroidal saponins) is the major active components of Huangshanyao and has demonstrated activities against oxidative stress, cancers, rheumatism, and injuries induced by reperfusion [13, 14, 16]. This traditional herb also could be used as an external drug to treat infectious diseases caused by microbial pathogens such as Lymphatic tuberculosis and Bacillus anthracis [16, 17].

The present study explores the antifungal activity of HSE against C. albicans, as well as the inhibitory effect on the C. albicans biofilms. The influence of HSE on the virulent factors was also evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extracts Preparation and Chemicals

The powdered saponins extract from the roots of Dioscorea panthaica Prain et Burk (Huangshanyao saponins extract, HSE) was provided and authorized by National Institute for Food and Drug Control of China (NIFDC). The lot number of the HSE powder is 110891-200001. For biological tests, HSE was solubilized in DMSO and stored at −20°C until use.

The standard reference compound pseudoprotodioscin (PPD) for Dioscorea panthaica Prain et Burk was also obtained from NIFDC. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), menadione, 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide (XTT), propidium iodide (PI), and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), as well as acetonitrile for high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China).

2.2. HPLC Analysis

HPLC analyses were performed on a Waters 2695 separation module (Waters Company, USA) equipped with a Waters 2996 photo-diode array (PDA) detector. HSE and standard compound PPD were dissolved in 50% acetonitrile. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 minutes, supernatants of both samples were transferred into sample vials and subjected to HPLC elution. HPLC separations were obtained on an Xterra MS C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 2.5 μM, Waters) at a temperature of 30°C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (mobile phase A) and 0.1% formic acid in ultrapure water (mobile phase B). The program for gradient elution was set as follows: 0–30 min, 15%–60% A, with a flow rate of 0.2 mL per minute. The volume for each HPLC analysis was set as 10 μL, while the monitoring wavelength was 220 nm.

2.3. Strains and Culture Conditions

C. albicans SC5314 was bought from China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) and stored at −80°C in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose in ddH2O) medium supplemented with 20% glycerol. Before assays, SC5314 were subcultured twice on YPD agars (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, and 1.8% agar) at 35°C. Prior to each assay, a colony of C. albicans on YPD agar was transferred into YPD broth and incubated at 28°C overnight with a speed of 140 rpm.

2.4. Effect of HSE on the Planktonic Growth of C. albicans

The effect of HSE on the growth of C. albicans was assessed according to the CLSI-M27-A3 guideline [18]. Briefly, C. albicans SC5314 cells from overnight grown cultures in YPD broth were harvested by centrifugation and adjusted to a final concentration of 2 × 103 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 medium (without sodium bicarbonate, pH 7.0). 100 μL of cell suspension was added to each well of 96-well plate (Corning, USA). HSE dissolved in DMSO was added to wells to achieve a twofold series of concentrations of HSE, ranging from 256 μg/mL to 4 μg/mL. Wells containing same volume of DMSO were set as negative controls, while wells treated with 4 μg/mL amphotericin B served as positive controls. Wells containing only medium were served as blank controls. After incubation at 35°C for 24 h, the inhibitory effect of HSE was assessed by visual inspection. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which no visual growth of C. albicans was observed.

To quantify the antifungal effect of HSE, MTT assay was performed as previously described [19]. Briefly, after visual inspection, 10 μL of sterile MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well of microplates, followed by another incubation at 35°C in dark for 4 h. Then, the supernatant in each well was discarded and 100 μL DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the water-insoluble formazan. A microplate reader (VarioSkan, Thermo, Germany) was used to detect the optical density (OD) at 570 nm. Viability of fungal cells in each well was calculated as viability = (OD570 treatment − OD570 blank)/(OD570 control − OD570 blank). These assays were performed three times.

2.5. Determination of the Minimum Fungicidal Concentration of HSE

The minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) of HSE was assessed as previously described [20]. At the end of 24 h incubation at 35°C, an aliquot of 10 μL from each well was taken, diluted serially, and plated on YPD agar. After incubation at 35°C for 48 h, the colonies grown on YPD agar were counted. The lowest concentration at which no colony of C. albicans grown on YPD agars was observed was defined as the MFC. These assays were performed for three times.

2.6. Time-Kill Curve Assay

To perform this assay, overnight grown C. albicans cultures in YPD broth were concentrated and diluted to a concentration of 106 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 medium. Cell suspensions supplemented with different concentrations of HSE were incubated at 28°C with shaking (140 rpm). At indicated time points, aliquots from each culture were withdrawn, serially diluted, and spotted onto YPD agars. After incubation at 37°C for 48 h, colony forming units (CFU) on each agar plate were determined. Three independent tests were performed [21].

2.7. The Effect of HSE on the Adhesion of C. albicans to Polystyrene Surface

The impact of HSE on the adhesion of C. albicans to the surface of polystyrene materials was assessed by the XTT reduction assay [22]. In brief, overnight cultured SC5314 cells were resuspended in 1640 medium to obtain a concentration of 106 cells/mL. 100 μL of that suspension was transferred into each well of 96-well plate and treated with different concentrations of HSE (0, 16, 32, and 64 μg/mL). After being incubated at 37°C for 90 minutes, wells were washed with sterile PBS for three times to remove nonadherent cells. XTT assay was carried out to determine the percentage of adherent cells of treatment wells comparing with negative controls. This assay was performed in triplicate and repeated for three times.

2.8. The Effect of HSE on Morphological Transition of C. albicans

This assay was performed as described previously [22]. C. albicans cells at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL in 1640 medium were incubated with different concentrations of HSE at 37°C. At indicated time points (3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h) after cells were added to 96-well plate, photos of biofilms treated with different concentrations of HSE were acquired by an inverted microscope (Olympus IX71, Japan). In addition, spider agar (1% mannitol, 1% nutrient broth, 0.2% K2HPO4, 1.8% agar, and pH 7.2) with different concentrations of HSE were prepared before smearing about 50 cells (in 100 μL 1640 medium) onto the solid agar to detect the effect of HSE on the morphological transition on solid agar. After 120 h incubation at 37°C, the morphologies of colonies were recorded by a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX-16, Japan). These assays were performed in triplicate.

2.9. The Effect of HSE on the Formation of C. albicans Biofilm

The inhibitory effect of HSE on C. albicans biofilm formation was assessed by XTT reduction assay [23]. Overnight grown cultures of C. albicans SC5314 in YPD medium were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 1640 medium to get a concentration of 106 cells/mL. 100 μL cell suspension containing different concentrations of HSE was added to each well of 96-well plate followed by sealing the plate with Parafilm. After 24 h incubation at 37°C, each well was washed with PBS for three times to remove the nonadherent cells. Then 100 μL sterile XTT solution was added to each well followed by another 2 h incubation. 75 μL supernatant from each well was transferred into fresh wells and the optical density at 490 nm was read with a VarioSkan multifunctional plate reader (Thermo, Germany). The assays were performed in triplicate and repeated for three times.

2.10. The Effects of HSE on the Preformed C. albicans Biofilm

The activity of HSE on the preformed biofilm was assessed with the same method as mentioned above [23]. After 24 h incubation without drugs, the 96-well plate containing biofilms was washed with PBS for three times to remove free-floating cells. Then fresh 1640 medium containing different concentrations of HSE was added to each well. After another 24 h incubation at 37°C, wells containing treated or nontreated biofilms were washed with PBS and XTT reduction assay was performed. The MIC for biofilm formation (MICbiofilm formation) and preformed biofilm (MICpreformed biofilm) were defined as the lowest concentration that inhibited more than 80% of the metabolic activity comparable to drug-free control biofilms. This assay was performed in triplicate and repeated for three times.

2.11. Analysis of C. albicans Biofilm Formation with Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope

C. albicans biofilms formed in 96-well plates at 37°C with different concentrations of HSE were washed with sterile PBS. The biofilms were incubated with 5 μM Syto® 9 (Molecular Probes, USA) for 10 minutes which could stain all the cells and fluorescence green, irrespective of cell viability. After being washed with PBS, biofilms were photographed by confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) (Olympus Fluoview FV1000, Japan) with an adjusted 40x objective lens (Olympus LCAch N, UIS2, Japan). The detailed 3D images of C. albicans biofilms were acquired using z-axis scanning (step size = 2 μm and the number of photo-slices is dependent on the height of biofilms). The three-dimensional images were reconstructed with Imaris 7.2.3 (Bitplane, Switzerland) to visualize the 3D structures of C. albicans biofilms.

2.12. The Effects of HSE on the Cell Membrane Integrity of C. albicans

The effect of HSE on the integrity of Candida cell membrane was evaluated by staining cell with fluorescent dye PI, which could only bind to DNA of dead cells because the integral membrane of live cells could prevent the access into cells. Briefly, Candida cells treated with different concentrations of HSE were incubated with 10 μM PI for half an hour in the dark at 37°C. After washing with PBS for twice, images of C. albicans cells were acquired by CLSM.

For quantitative analysis, following treatment and incubation with PI, cells were subjected to flow cytometry (FCM) (Beckman Coulter EPICS XL-MCL, USA) equipped with an argon laser (488 nm) for excitation to detect the fluorescent intensity of cells [24]. The percentage of PI stained cells was analyzed by Expo32 ADC analysis software (Beckman Coulter EPICS XL, USA). These assays were performed in triplicate and repeated for three times.

2.13. The Effects of HSE on the Endogenous Production of ROS

The capacity of HSE to induce endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) in C. albicans cells was investigated using the fluorescent probe DCFH-DA [25]. C. albicans suspensions at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL from overnight cultures were exposed to different concentration of HSE for 2 h before incubation with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 20 minutes. After washing with PBS for twice, samples were subjected to flow cytometry for ROS detection.

As for ROS production in mature biofilms in 96-well plate, DCFH-DA was added to wells with biofilms to achieve a concentration of 10 μM. After incubation for 20 minutes in dark at 37°C and removing excessive extracellular dye by washing, biofilms were incubated with indicated concentrations of HSE for 2 h in dark. The fluorescent intensity of biofilms was detected by VarioSkan multifunctional microplate reader at Ex 485 nm/Em 525 nm [24].

To further probe the influence of ROS on the antibiofilm activity of HSE, the metabolic viability of biofilms treated with HSE in the presence and absence of ROS inhibitor N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) was evaluated by XTT reduction assay as aforementioned. Before the viability assay, the morphologies of biofilms were photographed with microscope. The concentration of NAC used was 150 μg/mL, according to the previous study performed by others [24]. These assays were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

2.14. The Effects of HSE on the EPS Production of C. albicans

The EPS production of preformed C. albicans biofilms was evaluated by concentrated H2SO4-phenol method as previously described [26] with small modifications. C. albicans biofilms cultured under the same conditions as mentioned above for 24 h in 24-well plate were washed with PBS and fresh medium with different concentrations of HSE was added to each well. Following another 24 h incubation at 37°C, the supernatant was removed from each well and 200 μL 0.9% NaCl was added. An aliquot of 200 μL 0.5% phenol was added to each well prior to the gentle addition of 2 mL 0.2% hydrazine sulfate (w/v, in concentrated H2SO4). After incubation in dark for 1 h, the OD490 nm of each sample was read by a VarioSkan multifunctional plate reader. Assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

2.15. The Effect of HSE on the Production of Phospholipase

The production of phospholipase was evaluated by egg yolk agar method [26]. In brief, different concentrations of HSE in autoclaved egg yolk agar medium (NaCl 5.73%, 3% glucose, 1% peptone, 0.055% CaCl2, 10% egg yolk emulsion, 1.8% agar) were achieved as follows: after aseptic egg yolk emulsion was added to the autoclaved medium, and HSE stock solution was added to the medium and mixed well. 1 μL of overnight grown C. albicans culture (adjusted to 107 cells/mL) was transferred onto the agar. After 4 days' incubation at 37°C, for each colony, the diameter of colony and the diameter of colony plus the surrounding precipitation zone were determined. The precipitation zone (Pz) values were calculated as the ratio of the diameter of colony divided by that of the precipitation zones around the colony. The Pz values were employed to assess the activity of phospholipase as follows: Pz = 1, negative activity; Pz = 0.64~0.99, positive activity; and Pz < 0.64, very strong activity [27].

2.16. Cytotoxicity against Mammal Cells

MTT reduction assay was performed to assay the cytotoxicity of HSE to human Chang's liver cells [22]. Cell suspensions in DMEM medium (Gibco, China) plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) were seeded at 2 × 105 cells/mL into 96-well plates. After 24 h incubation with or without different concentrations of HSE at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, 10 μL sterile MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well followed by another incubation of 4 h at 37°C in dark. The formazan produced by cells of each well was dissolved in DMSO after the liquid of each well was removed and the OD values at 570 nm of each well were detected by a multifunctional plate reader. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

2.17. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 6.02 (GraphPad Software, USA). Statistical significance between treated and control groups was analyzed by Student's t-test with two-tailed and equal variance. Differences were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. HPLC Analyses

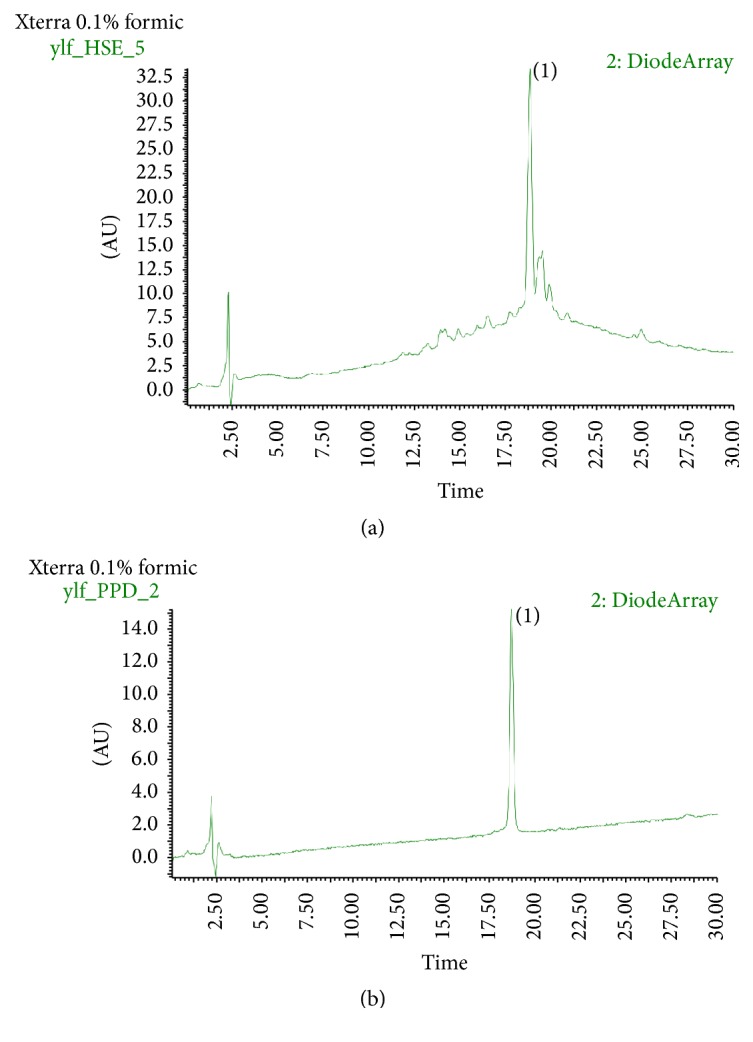

HPLC analyses were performed on a Waters 2695 separation module equipped with a 2996 detector, using acetonitrile (containing 0.1% formic acid) and ultrapure water (containing 0.1% formic acid) as mobile phases. HPLC spectrums were shown in Figure 1. PPD in this elution program has a retention time of 18.73 minutes.

Figure 1.

HPLC profiles at 220 nm of HSE and pseudoprotodioscin (PPD). (a) HSE, (b) PPD. Peak (1) is PPD with a retention time of 18.73 minutes. Separation was performed on a Waters 2695 equipped with a 2996 photo-diode array (PDA) detector. Mobile phase: (A) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile and (b) 0.1% formic acid in water. Flow rate: 0.2 mL/min. Column temperature: 30°C. Elution program: 0–30 min, 15%–60% A.

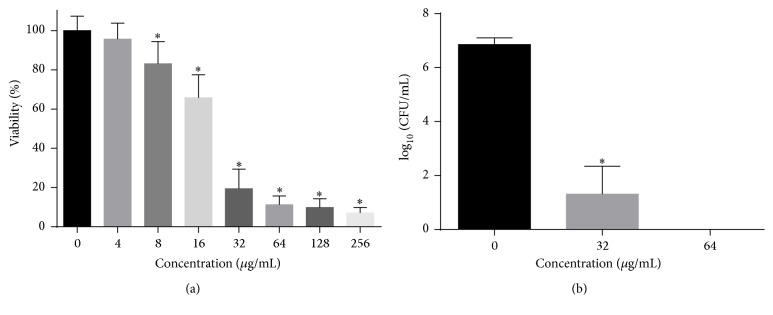

3.2. Antifungal Susceptibility

We performed antifungal tests according to CLSI-M27-A3 guidelines. As shown in Figure 2, the MIC value of HSE against C. albicans SC5314 was 32 μg/mL, while the MFC of HSE was 64 μg/mL. The MFC/MIC value was 2, indicating the effect of HSE on C. albicans was fungicidal.

Figure 2.

The antifungal activity of HSE on planktonic C. albicans cells. (a) MIC of HSE against C. albicans was determined by microdilution method. C. albicans cells were incubated with various concentrations of HSE for 24 h before MTT assay was performed. (b) MFC of HSE against C. albicans was obtained by counting the colonies grown on SD agars after serial dilution of each well and incubation at 37°C for 48 h. Data in the figures are average results from three independent tests. ∗ means p < 0.05. CFU, colony forming units.

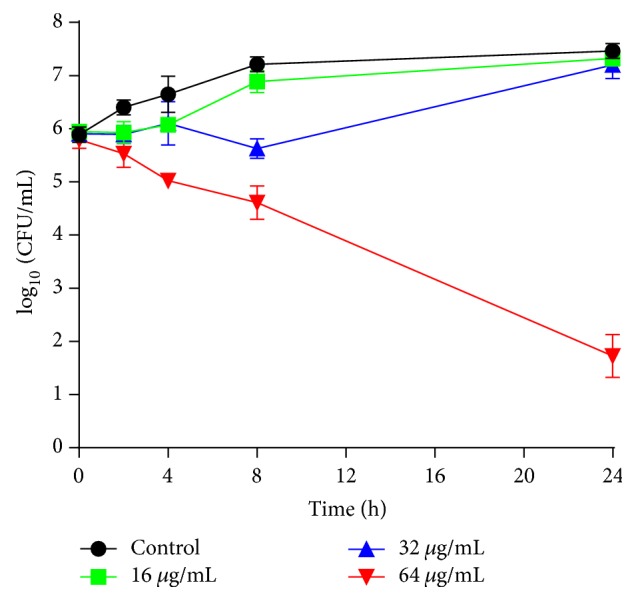

After the antifungal susceptibility, we performed time-kill assay. As shown in Figure 3, weak fungicidal effect was found. 16 μg/mL of HSE could only slow down the growth of C. albicans, while 32 μg/mL of HSE exerted fungicidal effect in the first 8 h before cells grown to almost 107 CFU/mL, similar to that of HSE-free controls. Treatment with 64 μg/mL HSE for 24 h attained strong fungicidal effect, yielding an about 4 log10 CFU/mL decrease compared to the beginning inoculum of the assay, which further corroborated the fungicidal effect of HSE, because the fungicidal effect could also be defined as a reduction more than 3 log10 CFU/mL from the initial inoculum in the time-kill assay [28].

Figure 3.

Time-kill curves of HSE against C. albicans SC5314. C. albicans suspension (106 cells/mL in RPMI-1640 medium) from overnight grown cultures was incubated with different concentrations of HSE at 28°C, 200 rpm. Cell suspension with the same volume DMSO was set as control. Data presented were means ± standard deviations from three independent tests.

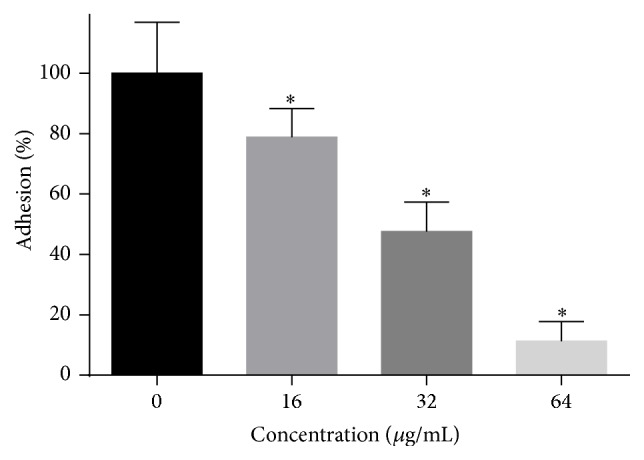

3.3. The Effects of HSE on Adhesion

Both infections and biofilm formation of C. albicans start from adhesion. Therefore, we examined the influence of HSE on the adhesion of C. albicans to polystyrene surfaces. The data we obtained showed that 16–64 μg/mL decreased the viability of adherent cells on the polystyrene surfaces (Figure 4). Treatment with 64 μg/mL of HSE inhibited approximately 80% of the adhesion as compared to the drug-free control groups. These data demonstrated that HSE could suppress the adhesion of C. albicans to polystyrene surfaces.

Figure 4.

The effect of HSE on the adhesion of C. albicans to polystyrene plates. C. albicans SC5314 in 1640 medium with certain concentrations of HSE were added to 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h, followed by an XTT assay to assess the adhesion rate of the cells compared to the control group. Data are shown as means + SDs, while ∗ means p < 0.05.

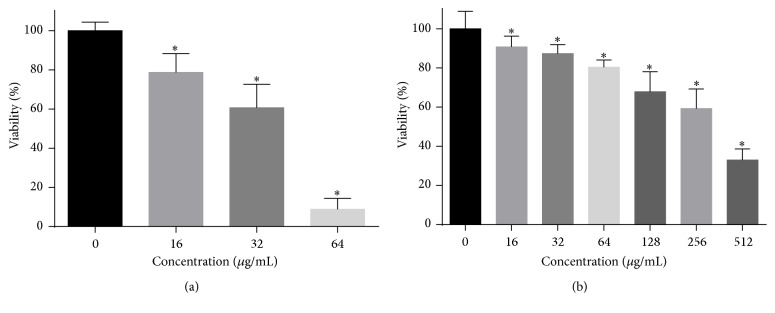

3.4. Antibiofilm Activity

The antibiofilm activity of HSE on C. albicans was evaluated by XTT reduction assay. Both the formation and development of C. albicans biofilms could be inhibited by HSE. As shown in Figure 5, 16–64 μg/mL HSE could inhibit about 30%–90% of biofilm formation as compared to those of drug-free controls. However, until the concentration as high as 256 μg/mL could HSE inhibit approximately 40% viability of preformed Candida biofilms.

Figure 5.

The antifungal activity of HSE on the C. albicans biofilm formation (a) and development (b). (a) C. albicans cells in 96-well plates were grown in the presence or absence of HSE at 37°C for 24 h and the metabolic activity of biofilms in each well was determined using XTT assay. (b) Twenty-four-hour mature C. albicans biofilms were exposed to various concentrations of HSE for another 24 h and the metabolic activities were compared to those of drug-free biofilms by an XTT reduction assay (∗p < 0.05).

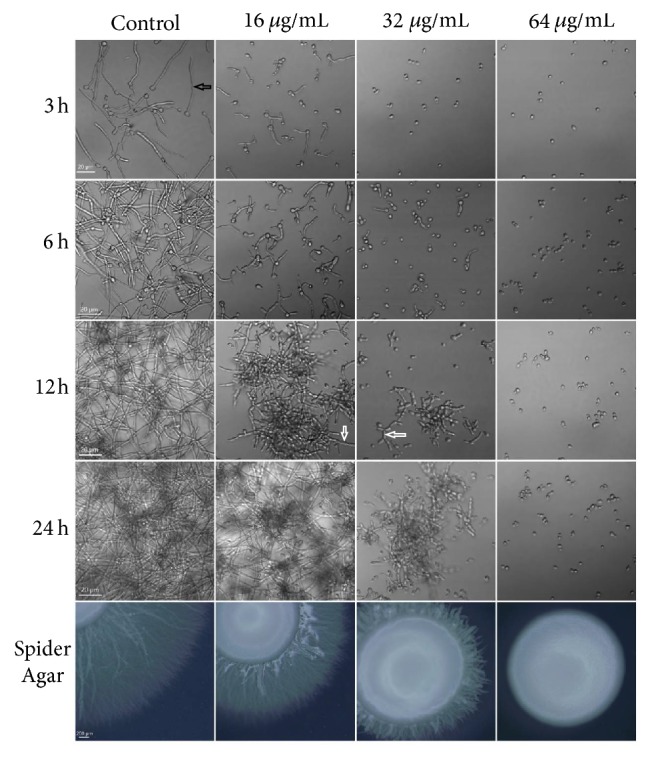

3.5. The Effects of HSE on Hyphal Growth

The transition from yeast to hyphae plays an important role in the pathogenesis of C. albicans infections and is considered as the most famous virulent trait of C. albicans. Therefore, we tested the effects of HSE on the yeast-to-hyphal transition. In the liquid RPMI-1640 medium and solid spider agar medium, 16–64 μg/mL markedly inhibited the transition in dose-dependent and time-dependent manner as demonstrated in Figure 6. In the liquid medium, cells in the control group formed true hyphae in 3 h and substantial hyphal networks in 24 h. Conversely, in comparison to control group, cells treated with 16 μg/mL of HSE retarded the hyphal growth as indicated by the decreased appearance of hyphae and shortened hyphal length in the first 6 h. Treatment with 32 μg/mL of HSE inhibited the formation of hyphae in 24 h and 64 μg/mL of HSE entirely suppressed the morphological transition of C. albicans. The capacity of HSE to suppress the hyphal formation was further confirmed by morphological changes in colonies on spider agar treated with different concentrations of HSE. Drug-free colonies formed radical shapes, while increased HSE concentrations resulted in smoother peripheral regions. In summary, HSE could inhibit the yeast-to-hyphal transition of C. albicans.

Figure 6.

The effect of HSE on the morphological transition of C. albicans. C. albicans SC5314 cells were challenged with different concentrations of HSE under hyphae-inducing conditions (at 37°C, in RPMI-1640 medium or on spider agar). The images were acquired by Olympus microscopes at indicated times. White arrows indicate pseudohyphae, while the black arrow indicates a hypha.

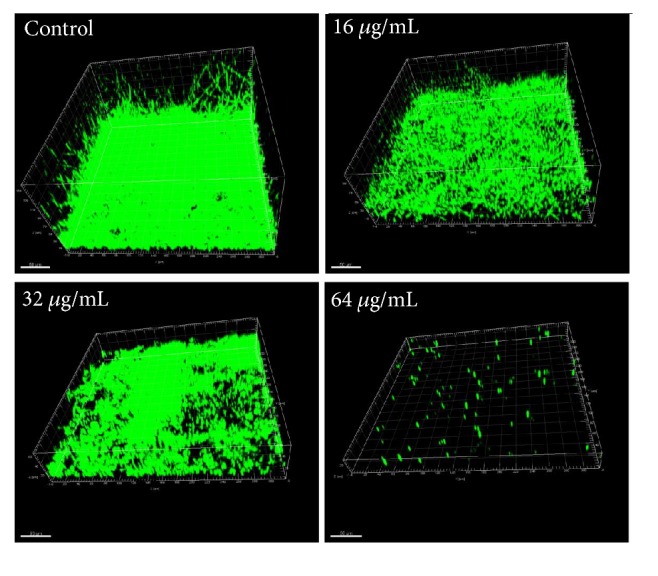

3.6. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope Analysis

The effects of HSE on the 3D structures of C. albicans biofilms were evaluated by CLSM. As shown in Figure 7, drug-free biofilms were robust with massive long hyphae pervading in the medium, while, in contrast, incubation with 16–32 μg/mL of HSE impaired the formation of biofilms significantly as indicated by the decreased heights of biofilms and the descending presence of hyphae. Moreover, 64 μg/mL of HSE completely prevented biofilm formation. This was consistent with the deceased viability caused by HSE obtained through XTT reduction assay (Figure 6).

Figure 7.

The effects of HSE on the formation of C. albicans biofilms. The biofilms were formed in the presence of different concentrations of HSE (0, 16, 32, and 64 μg/mL) for 24 h, followed by staining with Syto 9. Pictures were taken by CLSM using the xyz-scanning mode and reconstructed by Imaris 7.2.3.

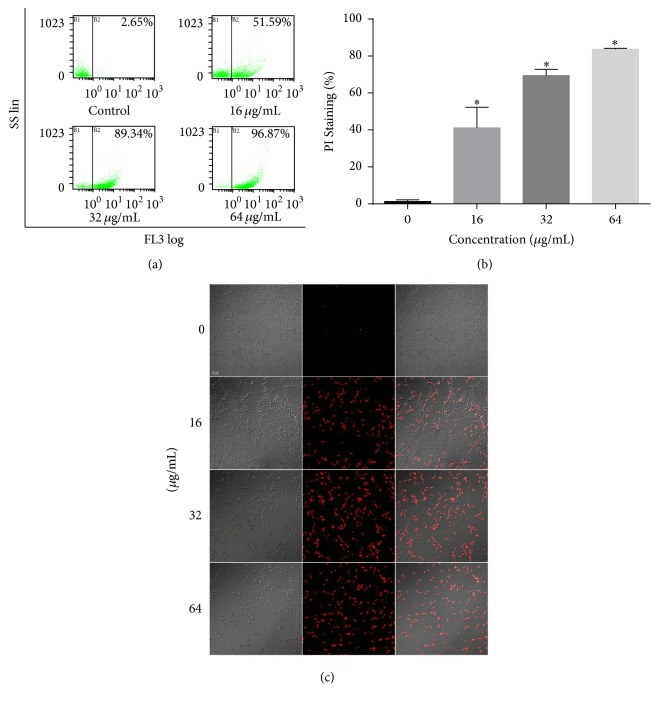

3.7. Cell Membrane Permeability

To further elucidate the possible mechanism underlying the antifungal activity of HSE, cell membrane integrity was evaluated by PI influx assay through CLSM. As demonstrated in Figure 8, HSE treatment resulted in increased PI influx in a dose-dependent way, indicating a membrane-disrupting action. To make a further step to quantify the PI influx caused by HSE, FCM was employed. Treatment with 16 μg/mL HSE caused above 50% membrane disruption of the population, while treatment with 32 μg/mL and 64 μg/mL of HSE induced about 90% and 96% PI-positive cells in the samples, respectively, consistent with the data acquired by CLSM. In summary, HSE treatment significantly increased the membrane permeability of C. albicans cells.

Figure 8.

HSE treatment increases the disruption of the plasma membrane integrity. (a) Candida cells treated with HSE were subjected to PI staining and FCM for cell membrane integrity analysis. (b) Summary of FCM assays for PI influx. (c) Representative confocal photos of PI staining samples treated with different concentrations of HSE. ∗p < 0.05.

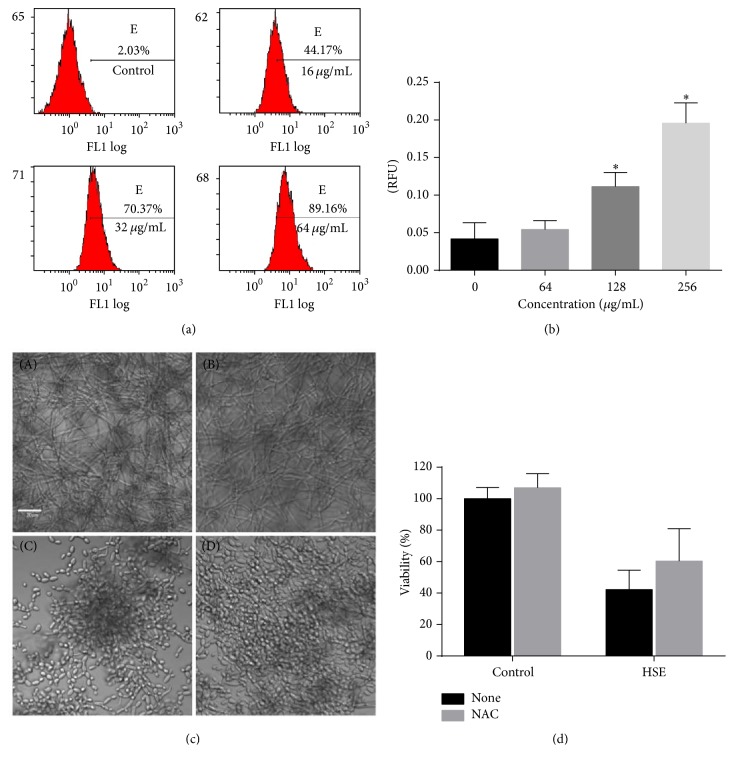

3.8. ROS Production in Planktonic and Biofilm Cells

Many drugs exert their antifungal effects through inducing endogenous ROS production which may impose oxidative damage to macromolecules such as DNA and proteins and finally influence the health and viability of cells [29–31]. So the accumulation of ROS was investigated by FCM using DCFH-DA staining. As shown in Figure 9, in planktonic growth, increasing the HSE concentration caused ascending ROS production. In the preformed biofilms, where the ROS production could not be detected readily by FCM method, in situ detection of ROS by microplate reader following preincubation with ROS probe was performed. As shown in Figure 9, treatment with HSE for 1 h resulted in obvious increase in the fluorescent intensity of ROS probe, indicating elevated ROS production in the mature C. albicans biofilms treated with HSE. To further probe the effects of ROS in the antibiofilm capacity of HSE, the antioxidant NAC was used. As shown in Figure 9, the presence of NAC rescued the viability of C. albicans biofilms, indicating that ROS are responsible for the antibiofilm activity of HSE.

Figure 9.

ROS involved in the antibiofilm activity of HSE. (a) HSE treatment increased the endogenous ROS production. Candida cells treated with different concentrations of HSE were subjected to FCM for ROS production analysis. (b) Treatment with HSE caused increased production of ROS in preformed biofilms. 24 h mature biofilms were incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min before washing with PBS, challenging with HSE and determining fluorescence with a multifunctional plate reader at 485 nm/525 nm (Thermo VarioSkan, Germany). (c) The presence of exogenous antioxidant NAC could restore the HSE-inhibited biofilm formation. (a) Negative control (DMSO); (b) DMSO + NAC; (c) HSE; (d) HSE + NAC. The concentration of NAC is 150 μg/mL, while HSE is 32 μg/mL. (d) Coincubation of 150 μg/mL of NAC with 32 μg/mL HSE could rescue part of the biofilm viability. ∗p < 0.05.

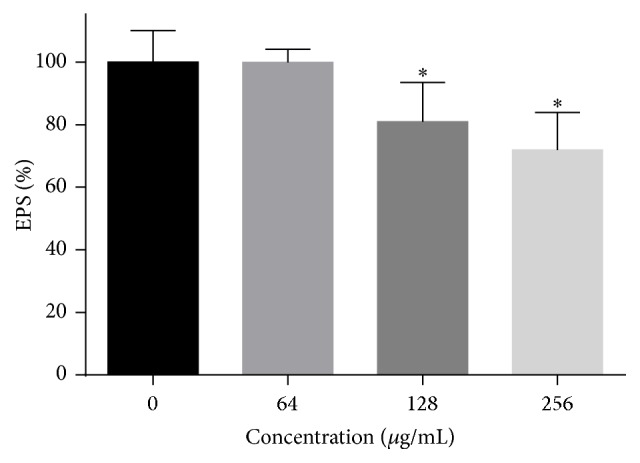

3.9. The Effects of HSE on the Production of EPS

Treatment with 64–256 μg/mL HSE decreased the production of EPS by 25–37% (Figure 10). Since EPS contribute to the resistance of C. albicans to antifungal drugs and the insusceptibility to human immune system, HSE might improve this by making cells in biofilm more accessible to drugs and the components of immune systems.

Figure 10.

HSE treatment could decrease the EPS of preformed C. albicans biofilms. After preformed biofilms were treated with different concentrations of HSE for 24 h, the concentrated H2SO4-phenol method was used to determine the EPS production of biofilms. ∗ means p < 0.05.

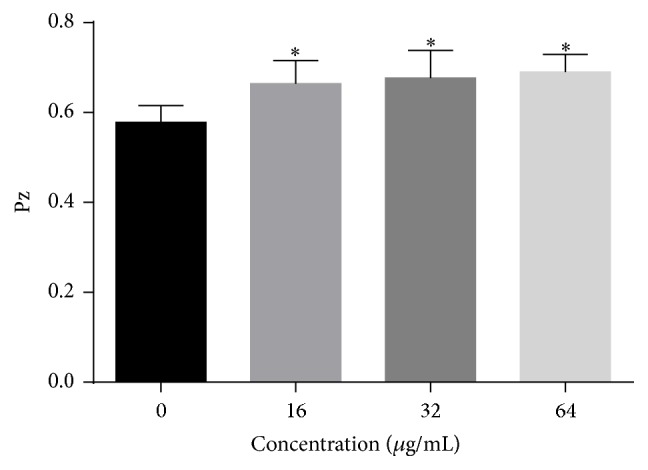

3.10. The Effects of HSE on the Production of Phospholipase

The effects of HSE on the phospholipase production of C. albicans were investigated. As demonstrated in Figure 11, increasing the concentrations of HSE resulted in decreased production of phospholipase as indicated by the increasing values of Pz.

Figure 11.

HSE decreased the production of extracellular phospholipase. Pz values were determined on egg yolk emulsion agar after incubation with or without different concentrations of HSE for 4 days at 37°C. Data shown were means + SD, while ∗ means p < 0.05 compared with drug-free samples.

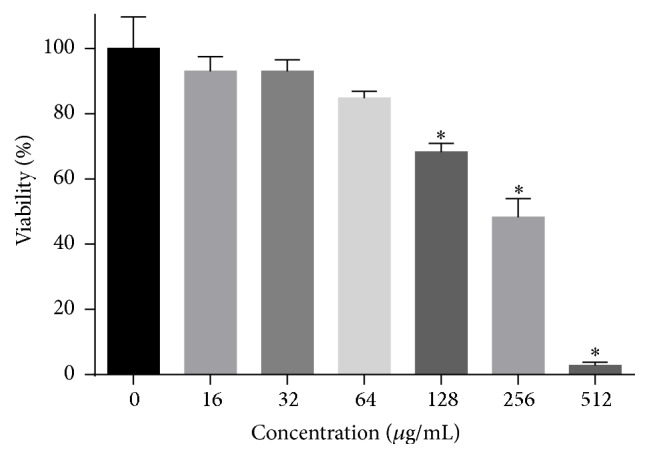

3.11. Cytotoxicity against Human Cells

In the MTT assay performed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of HSE to Chang's liver cells, HSE show low cytotoxicity with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) at above 200 μg/mL (Figure 12) which is much higher than the MIC and MFC value of HSE against C. albicans. This indicates that HSE may be less toxic or nontoxic for human cells.

Figure 12.

Cytotoxicity of HSE against Chang's liver cell determined by MTT assay. MTT assay was performed after treatment with different concentrations of HSE for 24 h. ∗p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The fungal pathogen C. albicans could impose serious health and economic burden on our society [32]. The paucity of antifungal drugs and problems with conventional therapeutics such as drug resistance, toxicity, side effects, and recurrence make developing novel antifungal agents against C. albicans a pressing mission [29, 33]. Various kinds of natural products with antifungal activity have been discovered [22, 34–38]. The health benefits of HSE have been shown by the marketed drug, and here, the aim of this research was to study the inhibitory effects of HSE on the proliferation, adhesion to biomaterial surfaces, morphological transition, phospholipase production, and biofilm formation of C. albicans.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research on the antifungal effects of HSE against both planktonic and biofilm types of C. albicans. In light of the definitions of fungicidal versus fungistatic effects [28, 34], the ratio of MFC to MIC was used to judge whether the antifungal agents had fungicidal (MFC/MIC < 4) or fungistatic (the ratio ≥ 4) effects [36]. Therefore, in our study the effect of HSE was considered as fungicidal, which was further validated by plasma integrity assay using fluorescent dye PI, because HSE could damage the cell membrane leading to PI influx.

Through the time-kill kinetics assay, the fungicidal effect of HSE was also validated according to another definition of fungicidal effects [28]. The results that 32 μg/mL of HSE exhibited inhibitory effect while 64 μg/mL of HSE showed strong fungicidal activity are consistent with MIC and MFC assay, although the culture conditions were different.

Adhesion, through specific cell surface adhesins, to a substrate is the first step of infection and biofilm formation. So inhibition of C. albicans cells adhesion could be a therapeutic target for preventing the incipient phases of Candida biofilm formation [39]. Consistent with many antifungal compounds exhibiting the capacity of inhibiting the adhesion of C. albicans, HSE also showed antiadhesion capacity [22, 34, 40, 41].

Hyphae act as an important part to the infection and biofilm formation. During the mucosal-associated infections, hyphae invade the epithelial and endothelial cells and thus introduce damage, during which the hydrolytic enzymes, such as phospholipase, play an important role [42]. The presence of hyphae makes the biofilm more cohesive, and it also helps C. albicans cells to cause damage to epithelial cells through candidalysin and to penetrate deeply into tissues [8]. So comes the thought that attenuating hyphal growth may possibly assuage hosts' damage [5]. Mutants incapable of forming hyphae could not induce damage to oral epithelial cells. Candidalysin secreted specifically by the hyphae of C. albicans also confirmed this thought indirectly [8]. During our study, HSE was able to suppress the hyphal growth of C. albicans both in the liquid medium and on the solid agar. Although solasodine-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside could both decrease the sizes of radical periphery and smooth center on spider agars, the natural compound purpurin could only inhibit the growth of peripheral wrinkles, while the diameters of smooth centers increased as the concentration of purpurin used increased, which is consistent with our results [22, 38].

From the results we obtained, it is conjectured that HSE may function well as a good antibiofilm agent since HSE inhibits hyphal development. Therefore, we examined the effects of HSE on biofilm formation by XTT reduction assay and confocal microscopy and found that HSE did inhibit the biofilm formation. In the biofilm formation, 32 μg/mL (MIC) of HSE could inhibit approximately 50% of biofilm viability, while 64 μg/mL (MFC) of HSE could almost entirely prevent the biofilm formation. Combining with the time-kill kinetics, this probably indicated that the antifungal effects of HSE depended on the maturity of C. albicans biofilm (MIC < MICbiofilm formation < MICpreformed biofilm).

As for preformed biofilms, our results showed that the concentration required for inhibiting 50% viability is much higher (approximately 8 times) than that of planktonic cells. This is the case many antifungal drugs have. The reason for increased tolerance might be that matured biofilms have accumulated extracellular matrix (predominately polysaccharides and proteins) which could prevent the access of drugs into cells within biofilms and strengthen the structures of biofilms [10, 43]. In our study, HSE could inhibit the EPS production of preformed biofilms, a characteristic of many antifungal compounds such as thiazolidinedione-8, usnic acid, and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol [26, 35, 44].

The fluorescent dye PI has been widely used to detect the membrane permeability because this membrane impermeable probe could only enter cells with permeability-compromised membrane [24, 34, 45]. FCM and CLSM assay showed that HSE caused significant damage to the plasma membrane of C. albicans cells, while the membrane-perturbation effects of HSE are akin to many other antifungal agents, for example, antimicrobial peptides, diphenyl diselenide, 3,5-di-tert-butylphenol, hibicuslide C, and thymoquinone [24, 45–48].

Although antioxidant activity of steroidal saponins of Dioscorea panthaica Prain et Burk has been documented [13], our current results showed that saponins extract of this herb could induce endogenous ROS in both planktonic and mature biofilm cells and the presence of antioxidant NAC could increase the viability of biofilms challenged by HSE. The discrepancy might result from the differences in the objects used. These results suggested that ROS might be responsible for the antibiofilm activity of HSE. ROS can facilitate damage to DNA, proteins, and cell membranes, resulting in the cell death [49]. The ROS production in C. albicans cells induced by HSE was in accordance with many ROS-inducing antifungal drugs such as amphotericin B, miconazole, and caspofungin [29].

The extracellular phospholipase could hydrolyze the phospholipids in the cell membrane, thus contributing to invasion and pathogenicity [50]. Mutants defective in phospholipase showed attenuated virulence in a systematic infection model of mouse [51, 52]. Moreover, the activity of extracellular phospholipase could be predictive of mortality [53]. Our data showed HSE could suppress the secretion of phospholipase, which was consistent with other antifungal agents such as 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol and quercetin [26, 54].

Many antifungal drugs failed because of toxicity, so we evaluate the toxicity of HSE toward human hepatoma cells. According to the results we obtained, HSE showed low cytotoxicity to Chang's liver cells.

5. Conclusions

The present study connoted that HSE has strong fungicidal activity against planktonic C. albicans. HSE could also inhibit virulence factors such as adhesion, filamentous growth, biofilm formation and development, and phospholipase production. The antifungal effects might be though membrane disruption and ROS production. Considering the negligible cytotoxicity and strong antifungal activity, as well as the fact that it is the main component of the marketed drug, HSE could be thought as a promising candidate for antifungal drug development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Li Guangquan for technical assistance. This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province [nos. 20160101344JC and 20180520118JH] and National Natural Science Foundation of China [no. 81401649]. Ms Wei Yingxiu of Sino Biological Inc. (Yiqiaoshenzhou Inc.) is specifically thanked for great help in preparing the chemical compounds. Dr. Yu Bo and Professor Yang Hong in Liaoning Normal University are specially thanked for the HPLC analysis during revising the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lippert R., Vojnovic S., Mitrovic A., et al. Effect of ferrocene-substituted porphyrin RL-91 on Candida albicans biofilm formation. 2014;24(15):3506–3511. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srinivasan A., Lopez-Ribot J. L., Ramasubramanian A. K. Overcoming antifungal resistance. 2014;11(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane S., Di Lena P., Tormanen K., Baldi P., Liua H. Function and regulation of Cph2 in Candida albicans. 2015;14(11):1114–1126. doi: 10.1128/EC.00102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong S. S. W., Samaranayake L. P., Seneviratne C. J. In pursuit of the ideal antifungal agent for Candida infections: high-throughput screening of small molecules. 2014;19(11):1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vediyappan G., Dumontet V., Pelissier F., d'Enfert C. Gymnemic acids inhibit hyphal growth and virulence in Candida albicans. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074189.e74189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haque F., Alfatah M., Ganesan K., Bhattacharyya M. S. Inhibitory effect of sophorolipid on Candida albicans biofilm formation and hyphal growth. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep23575.23575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert A. S., Wheeler R. T., May R. C. Fungal pathogens: survival and replication within macrophages. 2015;5(7) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019661.a019661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyes D. L., Wilson D., Richardson J. P., et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. 2016;532(7597):64–68. doi: 10.1038/nature17625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nett J., Andes D. Candida albicans biofilm development, modeling a host-pathogen interaction. 2006;9(4):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nobile C. J., Mitchell A. P. Genetics and genomics of Candida albicans biofilm formation. 2006;8(9):1382–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roemer T., Xu D., Singh S. B., et al. Confronting the challenges of natural product-based antifungal discovery. 2011;18(2):148–164. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cragg G. M., Newman D. J. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. 2013;1830(6):3670–3695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W., Li P., Wang X., Jing W., Chen L., Liu A. Quantification of saponins in Dioscorea panthaica Prain et Burk rhizomes with monolithic column using rapid resolution liquid chromatography coupled with a triple quadruple electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. 2012;71:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W., Zhao Y., Jing W., et al. Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography-ion trap mass spectrometry characterization of the steroidal saponins of Dioscorea panthaica Prain et Burkill and its application for accelerating the isolation and structural elucidation of steroidal saponins. 2015;95:51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo L., Zeng S.-L., Zhang Y., Li P., Liu E.-H. Comparative analysis of steroidal saponins in four Dioscoreae herbs by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. 2016;117:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong M., Feng X.-Z., Wang B.-X., Wu L.-J., Ikejima T. Two novel furostanol saponins from the rhizomes of Dioscorea panthaica prain et burkill and their cytotoxic activity. 2001;57(3):501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(00)01024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y., Wang W., Jing W., Liu A. Advances on chemical constituents, pharmacological effects and clinical applications of dioscorea panthaicae rhizoma. 2014;20:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wayne, Pa, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2008. Reference Method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Da Silva A. R., De Andrade Neto J. B., Da Silva C. R., et al. Berberine antifungal activity in fluconazole-resistant pathogenic yeasts: action mechanism evaluated by flow cytometry and biofilm growth inhibition in Candida spp. 2016;60(6):3551–3557. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01846-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shokri H., Sharifzadeh A. Fungicidal efficacy of various honeys against fluconazole-resistant Candida species isolated from HIV(+) patients with candidiasis. 2017;27(2):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li D.-D., Zhao L.-X., Mylonakis E., et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of pterostilbene against Candida albicans biofilms. 2014;58(4):2344–2355. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01583-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y., Chang W., Zhang M., Ying Z., Lou H. Natural product solasodine-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside inhibits the virulence factors of Candida albicans. 2015;15(6) doi: 10.1093/femsyr/fov060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierce C. G., Uppuluri P., Tristan A. R., et al. Simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. 2008;3(9):1494–1500. doi: 10.1038/nport.2008.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rathna J., Bakkiyaraj D., Pandian S. K. Anti-biofilm mechanisms of 3,5-di-tert-butylphenol against clinically relevant fungal pathogens. 2016;32(9):979–993. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2016.1216103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun D. G., Lee D. G. Silibinin triggers yeast apoptosis related to mitochondrial Ca2+ influx in Candida albicans. 2016;80:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padmavathi A. R., Bakkiyaraj D., Thajuddin N., Pandian S. K. Effect of 2, 4-di-tert-butylphenol on growth and biofilm formation by an opportunistic fungus Candida albicans. 2015;31(7):565–574. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2015.1077383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu W., Guo D., Zhang L., Xu D., Sun S. The synergistic effect of azoles and fluoxetine against resistant Candida albicans strains is attributed to attenuating fungal virulence. 2016;60(10):6179–6188. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03046-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobudic S., Forstner C., Schranz H., Poeppl W., Vychytil A., Burgmann H. Comparative in vitro fungicidal activity of echinocandins against Candida albicans in peritoneal dialysis fluids. 2013;56(6):623–630. doi: 10.1111/myc.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delattin N., Cammue B. P., Thevissen K. Reactive oxygen species-inducing antifungal agents and their activity against fungal biofilms. 2014;6(1):77–90. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Cremer K., De Brucker K., Staes I., et al. Stimulation of superoxide production increases fungicidal action of miconazole against Candida albicans biofilms. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep27463.27463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferreira G. F., Baltazar L. D. M., Santos J. R., et al. The role of oxidative and nitrosative bursts caused by azoles and amphotericin B against the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus gattii. 2013;68(8):1801–1811. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nobile C. J., Johnson A. D. Candida albicans biofilms and human disease. 2015;69(1):71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odds F. C., Brown A. J. P., Gow N. A. R. Antifungal agents: Mechanisms of action. 2003;11(6):272–279. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(03)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun L., Liao K., Wang D. Effects of magnolol and honokiol on adhesion, yeast-hyphal transition, and formation of biofilm by candida albicans. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117695.e0117695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nithyanand P., Beema Shafreen R. M., Muthamil S., Karutha Pandian S. Usnic acid inhibits biofilm formation and virulent morphological traits of Candida albicans. 2015;179:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peixoto L. R., Rosalen P. L., Ferreira G. L. S., et al. Antifungal activity, mode of action and anti-biofilm effects of Laurus nobilis Linnaeus essential oil against Candida spp. 2017;73:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao L.-X., Li D.-D., Hu D.-D., et al. Effect of tetrandrine against Candida albicans biofilms. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079671.e79671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsang P. W.-K., Bandara H. M. H. N., Fong W.-P. Purpurin suppresses Candida albicans Biofilm formation and hyphal development. 2012;7(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050866.e50866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rane H. S., Bernardo S. M., Howell A. B., Lee S. A. Cranberry-derived proanthocyanidins prevent formation of Candida albicans biofilms in artificial urine through biofilm- and adherence-specific mechanisms. 2014;69(2):428–436. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raut J. S., Shinde R. B., Chauhan N. M., Karuppayil S. M. Terpenoids of plant origin inhibit morphogenesis, adhesion, and biofilm formation by Candida albicans. 2013;29(1):87–96. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2012.749398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fazly A., Jain C., Dehner A. C., et al. Chemical screening identifies filastatin, a small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicans adhesion, morphogenesis, and pathogenesis. 2013;110(33):13594–13599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305982110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Castro P. A., Bom V. L. P., Brown N. A., et al. Identification of the cell targets important for propolis-induced cell death in Candida albicans. 2013;60:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nett J. E., Sanchez H., Cain M. T., Andes D. R. Genetic basis of Candida biofilm resistance due to drug-sequestering matrix glucan. 2010;202(1):171–175. doi: 10.1086/651200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feldman M., Shenderovich J., Al-Quntar A. A. A., Friedman M., Steinberg D. Sustained release of a novel anti-quorum-sensing agent against oral fungal biofilms. 2015;59(4):2265–2272. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04212-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maurya I. K., Thota C. K., Sharma J., et al. Mechanism of action of novel synthetic dodecapeptides against Candida albicans. 2013;1830(11):5193–5203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang J. H., Jin Q., Woo E.-R., Lee D. G. Antifungal property of hibicuslide C and its membrane-active mechanism in Candida albicans. 2013;95(10):1917–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosseti I. B., Rocha J. B. T., Costa M. S. Diphenyl diselenide (PhSe)2 inhibits biofilm formation by Candida albicans, increasing both ROS production and membrane permeability. 2015;29:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Almshawit H., Macreadie I. Fungicidal effect of thymoquinone involves generation of oxidative stress in Candida glabrata. 2017;195:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imlay J. A. Pathways of oxidative damage. 2003;57:395–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayer F. L., Wilson D., Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. 2013;4(2):119–128. doi: 10.4161/viru.22913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leidich S. D., Ibrahim A. S., Fu Y., et al. Cloning and disruption of caPLB1, a phospholipase B gene involved in the pathogenicity of Candida albicans. 1998;273(40):26078–26086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Theiss S., Ishdorj G., Brenot A., et al. Inactivation of the phospholipase B gene PLB5 in wild-type Candida albicans reduces cell-associated phospholipase A2 activity and attenuates virulence. 2006;296(6):405–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. 2007;5(1):48–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh B. N., Upreti D. K., Singh B. R., et al. Quercetin sensitizes fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans to induce apoptotic cell death by modulating quorum sensing. 2015;59(4):2153–2168. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03599-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]