Abstract

32P high-dose rate brachytherapy allows high-dose radiation delivery to target lesions with less damage to adjacent tissues. The early evaluation of its therapeutic effect on tumours is vital for the optimization of treatment regimes. The most commonly used 32P-CP colloid tends to leak with blind therapeutic area after intratumour injection. We prepared 32P-chromic phosphate-polylactide-co-glycolide (32P-CP-PLGA) seeds with biodegradable PLGA as a framework and investigated their characteristics in vitro and in vivo. We also evaluated the therapeutic effect of 32P-CP-PLGA brachytherapy for glioma with the integrin αvβ3-targeted radiotracer 68Ga-3PRGD2. 32P-CP-PLGA seeds (seed group, SG, 185 MBq) and 32P-CP colloid (colloid group, CG, 18.5 MBq) were implanted or injected into human glioma xenografts in nude mice. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the seeds, micro-SPECT imaging, and biodistribution studies were performed at different time points. The tumour volume was measured using a caliper, and 68Ga-3PRGD2 micro-PET-CT imaging was performed to evaluate the therapeutic effect after 32P intratumour administration. The delayed release of 32P-CP was observed with biodegradation of vehicle PLGA. Intratumoural effective half-life of 32P-CP in the SG (13.3 ± 0.3) d was longer than that in the CG (10.4 ± 0.3) d (P < 0.05), with liver appearance in the CG on SPECT. A radioactivity gradient developed inside the tumour in the SG, as confirmed by micro-SPECT and SEM. Tumour uptake of 68Ga-3PRGD2 displayed a significant increase on day 0.5 in the SG and decreased earlier (on day 2) than the volume reduction (on day 8). Thus, 32P-CP-PLGA seeds, controlling the release of entrapped 32P-CP particles, are promising for glioma brachytherapy, and 68Ga-3PRGD2 imaging shows potential for early response evaluation of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds brachytherapy.

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) accounts for approximately 60% to 70% of malignant gliomas. The prognosis of patients with GBM remains dismal, with a median survival time of less than one year. This poor prognosis primarily reflects the high proliferative, infiltrative, and invasive properties of GBM [1]. Systemic administration of most potentially active drugs is not effective because of failing to cross the blood-brain barrier. Residual cells at the margins of the resection or GBM stem cells, a subpopulation of stem-like cells, frequently lead to tumour recurrence or metastasis.

Compared with external-beam radiation, brachytherapy has the advantage of delivering high doses of radiation to target sites without subjecting normal tissues to undue radiation and damage [2]. 32P is ideal because of its relatively long half-life of 14.28 day(s), maximum energy of 1.711 MeV, mean range of 3-4 mm in soft tissues, and high relative biological effect. Recent studies have focused on better vehicles or carriers, and many of these studies have used 32P bandages or films for the brachytherapy of superficial cancers and intracranial and spinal tumours [3–9]. However, the main hurdles to these vehicles were poor target ratios in the tumour, complex preparation, and serious side effects resulting from migration and permanent stagnation, such as lung migration and gastric fistula in vivo [7–9].

Polymers, such as poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), and their copolymer poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), have extensively been used in drug delivery systems because of their biodegradability, tissue compatibility, and versatile degradation kinetics [10–13]. Compared with poly(L-lactide) (PLLA), PLGA has attracted more attention, reflecting its degradation rate and relative ease in manipulating its release of encapsulating drugs by changing the degradation-determining factors, such as its molecular weight, lactide/glycolide ratio, and degree of crystallinity [14, 15]. In a previous study, we completed the formulation and determined the fabricating parameters of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds (unpublished observations). As one potential biodegradable seed for brachytherapy, 32P-CP-PLGA is meaningful for further preclinical studies, and the therapeutic effect evaluation of 32P brachytherapy has rarely been reported.

Integrin αvβ3, specifically targeted by the arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) tripeptide sequence, is highly expressed in both glioma cells and neovasculature but not in quiescent blood vessels. Integrin αvβ3 targeted imaging had higher sensitivity in GBM than 18F-FDG, reflecting a clear lack of RGD affinity, particularly in brain areas where gliomas are prone to occur [16]. In an orthotopic U87MG human glioma mouse model, the tumour-to-brain ratio of radiolabelled RGD is approximately 20 times that of 18F-FDG [17]. 68Ga, easily accessible via elution from the 68Ge-68Ga generator, can produce Cerenkov radiation and allow the combination of PET-Cerenkov luminescence imaging (CLI) for both tumour diagnosis and visual guidance for further surgery [17]. 68Ga-labelled DOTA-3PRGD2 (68Ga-3PRGD2) was reported to reflect the tumour response to antiangiogenic therapy much earlier and more accurately than 18F-FDG PET imaging [18]. Integrin-targeted imaging detects early responses preceding clinical regression as early as day 3 after the initiation of abraxane treatment, while 18F-FDG imaging demonstrated increased tumour uptake on days 3 and 7 [19]. For 32P brachytherapy, early response is also important for treatment direction; however, few studies have been reported.

In our previous study, we found that radiolabelling RGD is excellent for monitoring αvβ3 expression and glioma necrosis during tumour growth [20]. The present study reports (a) the preparation, biodegradation, and ultrastructural changes of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds and the biodistribution of 32P-CP particles both systemically and inside the tumour and (b) the anticancer effect on glioma in an animal model after intratumour seeds implantation and therapeutic effect evaluation with integrin αvβ3 receptor targeting radiotracer 68Ga-3PRGD2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

32P-CP colloid, supplied by Beijing Atom High-Tech Co., Ltd., China, is a green colloid solution with radioactive chemical purity > 98%, particle size 20~50 nm, and specific radioactivity ~ 1850 MBq/ml. PLGA (50 : 50; MW-85,000 Da) was obtained from Hefei University of Technology, China. 68Ge-68Ga generator (ITG, Germany), 3PRGD2, was donated by Dr. Shuang Liu (Purdue University). Nude mice (male, 14–16 g, 5-6 weeks) bearing human glioma (U87MG) xenografts in the flank were obtained from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, China. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the standards of the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee. The following were used: hamster anti-integrin β3 antibody (1 : 100, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), rat anti-CD31 antibody (1 : 100, BD Biosciences), Cy3-conjugated goat anti-hamster secondary antibody (1 : 100, Jackson Immuno Research Inc., West Grove, PA), fluorescein- (FITC-) conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibody (1 : 100, Jackson Immuno Research Inc., West Grove, PA), CRC-Enhanced β calculator (Capintec Corporation, USA), Gamma counter (TY6017, Wizard, PerkinElmer, USA), Electronic Balance (BS-110S, Sartorius Corporation, Germany), Scanning electron microscope (S-3000N, Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Japan), Olympic BX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA), micro-SPECT (Milabs, Utrecht, The Netherlands), and micro-PET/CT (Inveon, Siemens, Germany).

2.2. Preparation of 32P-CP-PLGA Seeds and In Vitro Study

A total of 100 mg of PLGA (0.1–1.0 μm) and 2 ml of colloidal 32P-CP (1850 MBq/ml) were mixed with 2-3 ml of dehydrated alcohol as a dispersing agent. These components were blended and dried at 60°C in a vacuum drying oven for 9–12 h. Magnesium stearate (1.0–1.5 mg) served as a surface lubricant, and the 32P-CP-PLGA seeds were home-prepared using an automatic precise piercer. The physical characteristics of the 32P-CP-PLGA seeds were investigated. In vitro releasing experiments were performed by incubating the 32P-CP-PLGA seeds in 6 ml of PBS at 37°C for 90 day(s), and 0.2 ml of the sample was withdrawn every other day from the releasing solution after stirring to generate a homogenous mixture.

2.3. Radiopharmaceutical Administration and Biodistribution Study

Nude mice bearing U87MG human gliomas (tumour long diameter of 0.6–0.8 cm) were randomized into the 32P-CP-PLGA seed group (SG, n = 36) and the 32P-CP colloid group (CG, n = 36). One 32P-CP-PLGA seed (18.5 MBq) or 0.02 ml of colloidal 32P-CP (18.5 MBq) was implanted or slowly injected into the tumour core. The injection sites were gently compressed for 60 s. The mice were sacrificed at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 49, and 64 days (5 mice each time point each group) for biodistribution study and pathology examination.

Important organs were harvested, weighed, and counted for radioactivity using a β calculator or Gamma counter. Tumour xenografts harvested at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 16 days were further divided into 3 parts according to their distances from the core of the tumour. The 3 parts of the tumour and adjacent tissues were weighed and counted for radioactivity. 32P distribution was expressed as the percent injected dose per gram (%ID/g). The remaining seeds and tumour tissues were prepared for SEM examination. For the mice sacrificed on day 64, micro-SPECT imaging was selectively performed, and faeces and urine were collected.

2.4. Micro-SPECT and Micro-SPECT/CT Imaging

Anesthesia of mice (SG and CG) was induced using isoflurane. Micro-SPECT images were obtained on days 1, 4, 16, and 64 using a micro-SPECT scanner equipped with a 0.6 mm multipinhole collimator. The specified 32P-CP-PLGA seeds and 32P-CP colloids, same as those used in the SG and CG, were served as markers and imaged, respectively. Regions of interest (ROIs) of the targeted tumour (T) and the marker (Tmk) were drawn to estimate the T/Tmk ratio and intratumoural effective half-life of 32P-CP. After SPECT acquisition (75 projections over 30 min per frame, 2 frames), SPECT reconstruction was performed using a POSEM (pixelated ordered subsets by expectation maximization) algorithm with 6 iterations and 16 subsets. Micro-CT imaging was added on day 1 using the “normal” acquisition settings at 45 kV and 500 A. CT data were reconstructed using a cone-beam filtered back-projection algorithm (NRecon v1.6.3, Skyscan). After reconstruction, the SPECT and CT data were automatically coregistered according to the movement of the robotic stage and then resampled to equivalent voxel sizes. Coregistered images were further rendered and visualized using PMOD software (PMOD Technologies, Zurich, Switzerland).

2.5. Therapeutic Effect of 32P-CP-PLGA Seeds for Gliomas

39 nude mice bearing U87MG gliomas (long diameter of 0.6–0.8 cm) were randomly divided into 32P-CP-PLGA seed group (18.5 MBq, n = 17), 32P-CP colloid group (18.5 MBq, 0.02 ml, n = 5), and P-CP-PLGA seed group (no radioactivity, n = 17). Tumour diameter was measured with digital caliper every other day and tumour volume was estimated by the formula (length × width2)/2 (5 mice each group for three group). 68Ga-3PRGD2 micro-PET-CT imaging was performed on days 0.5, 2, 8, and 16 after seeds administration (n = 5 of each group). Four mice were sacrificed on days 0.5, 2, and 4 in SG and P-CP-PLGA seed group and tumour xenografts were harvested for immunohistochemistry (IHC) examination.

2.6. 68Ga-3PRGD2 Micro-PET-CT Imaging

We prepared 68Ga-3PRGD2 as previously described [18]. In brief, 68GaCl3 was eluted from 68Ge/68Ga-generator with 0.05 M HCl. The conjugation of 3PRGD2 with DOTA-OSu was performed for the synthesis of DOTA-3PRGD2. The DOTA-3PRGD2 and 68GaCl3 were mixed and heated in a water bath at 90°C for 15 min. The radiochemical purity was then determined with radio-HPLC.

0.1 mL of 68Ga-3PRGD2 (74 MBq/mL) was injected via tail vein under isoflurane anesthesia. Ten-minute static PET scans were acquired and images were reconstructed by an OSEM 3D (Three-Dimensional Ordered Subsets Expectation Maximum) algorithm followed by MAP (Maximization/Maximum A Posteriori). The 3D ROIs were drawn over the tumour guided by CT images and tracer uptake was measured using the software of Inveon Research Workplace (IRW) 3.0. Mean standardized uptake values (SUV) were determined by dividing the relevant ROI concentration by the ratio of the injected activity to the body weight.

2.7. Seeds Ultrastructure Changes and Glioma Integrin αvβ3 Expression

SEM examination was performed to investigate the ultrastructure changes of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds. Frozen glioma tissues were cut into 5 μm slices and blocked with 10% goat serum for 30 min and then incubated with the hamster anti-integrin β3 antibody and rat anti-CD31 antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After incubating with the Cy3-conjugated goat anti-hamster and fluorescein- (FITC-) conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibodies and washing with PBS, the fluorescence was visualized using a fluorescence microscope.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are shown as mean ± SD. Differences in tissues uptake between SG and CG were statistically analyzed at each time point with SPSS 11.5 software. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics and Biodegradation of 32P-CP-PLGA Seeds

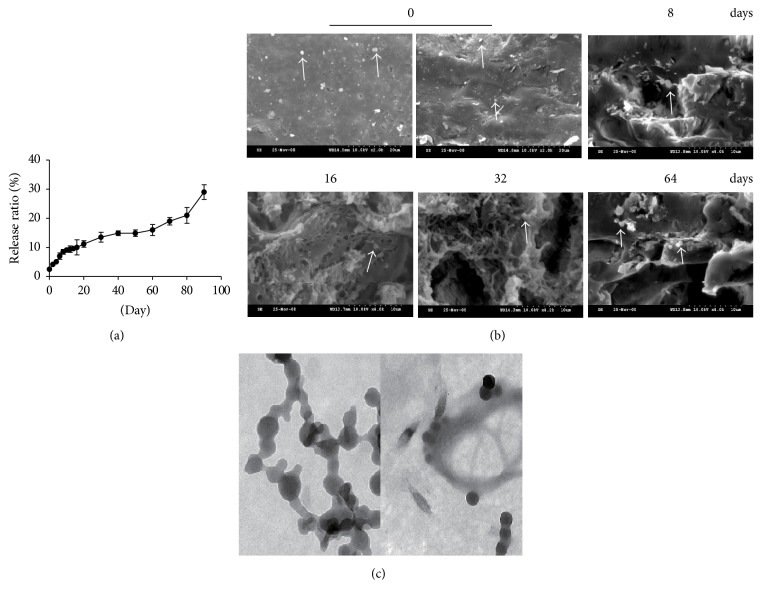

32P-CP-PLGA seeds are cylindrical with a diameter of (0.9 ± 0.02) mm, length of (1.9 ± 0.2) mm, weight of (1.2 ± 0.15) mg each, hardness of (5.7 ± 1.4) N, and apparent radioactivity of (18.5 ± 3.7) MBq. The release of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds can be divided into the rapid release phase (0~8 d, phase I), the stable release phase (8~60 d, phase II), and the disintegration release phase (60 d ~, phase III) according to time-release curve slope (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Time-release curve of 32P-CP particles from 32P-CP-PLGA seeds and ultrastructure changes of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds by SEM in vitro. (a) In vitro releasing experiment was performed by incubating the 32P-CP-PLGA seeds in 6.0 ml of PBS at 37°C for 90 day(s). (b) SEM was performed before day 0 (left: surface; right: cross-section) and 8, 16, 32, and 64 day(s) after intratumoural implantation. 32P-CP particles, indicated with white arrow, encapsulated in the seeds and released with the structure erosion of carrier PLGA polymer. (c) The ultrastructure of 32P-CP particles released from the PLGA in vitro (50 nm).

Figure 1(b) displays the SEM results of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds before and 8, 16, 32, and 64 days after intratumour implantation. The seed was uniform and dense in texture, showing a mosaic of 32P-CP particles prior to implantation. An increasing number of micropores, tunnels, cellular structures, cavities, and fragments were observed with increasing seed brittleness and inability to maintain shape during release. Figure 1(c) displays the ultrastructure of 32P-CP particles before the preparation of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds and those released from the 32P-CP-PLGA seeds.

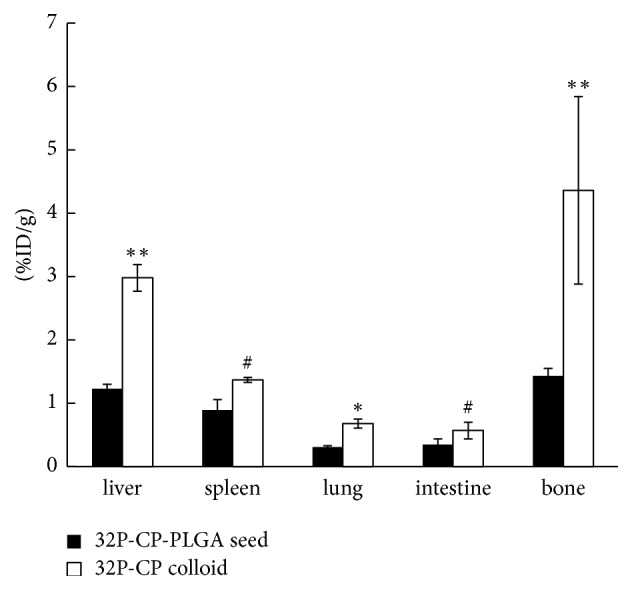

3.2. Biodistribution of 32P-CP Particles

The biodistribution of 32P-CP in SG and CG is shown in Tables 1 and 2. The released radioactivity reached up to (7.3 ± 1.4)% on day 8 and increased to approximately (21 ± 3.8)% on day 64, among which approximately (14.6 ± 2.7)% remained in the tumour, (5.2 ± 1.3)% was primarily aggregated in the liver, spleen, and bone, and approximately (3.1 ± 0.86)% was eliminated in faeces and urine. Leakage of 32P-CP colloid was detected around the tumour xenograft in the CG. Compared with the CG, the peak uptake of 32P-CP in the liver (3.1 ± 0.3)%, spleen (1.3 ± 0.1)%, and bone (4.3 ± 1.8)% was significantly less in the SG [(1.2 ± 0.1)% in liver, (0.8 ± 0.2)% in spleen, and (1.5 ± 0.1)% in the bone, all of P < 0.05] (Figure 2). Intratumoural radioactive effective half-life of 32P-CP in the SG (13.3 ± 0.3 d) was longer than that in the CG [(11.4 ± 0.7) d, P < 0.05]. Pathological examination of the liver, spleen, lung, and bone demonstrated no abnormality in the SG.

Table 1.

Biodistribution of 32P-CP particle in nude mice bearing U87MG glioma after intratumor implantation of 32P-CP-PLGA seed (n = 5).

| Tissue | Radioactivity distribution (%ID/g) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 d | 1 d | 2 d | 4 d | 8 d | 16 d | 32 d | 48 d | 64 d | ||

| Tumor | Mean 1 SD |

556.686 24.016 |

547.778 61.301 |

626.172 76.528 |

666.063 59.454 |

724.118 132.290 |

903.226 128.155 |

—— | —— | —— |

| Blood | Mean 1 SD |

0.007 0.004 |

0.008 0.008 |

0.016 0.008 |

0.020 0.017 |

0.017 0.013 |

0.018 0.011 |

0.010 0.000 |

0.019 0.005 |

0.010 0.004 |

| Heart | Mean 1 SD |

0.028 0.012 |

0.046 0.013 |

0.079 0.011 |

0.167 0.015 |

0.213 0.006 |

0.128 0.024 |

0.062 0.015 |

0.018 0.011 |

0.027 0.012 |

| Liver | Mean 1 SD |

0.020 0.010 |

0.035 0.082 |

0.179 0.115 |

0.656 0.136 |

1.125 0.038 |

0.738 0.100 |

0.430 0.037 |

0.369 0.041 |

0.165 0.016 |

| Spleen | Mean 1 SD |

0.031 0.030 |

0.069 0.028 |

0.369 0.121 |

0.556 0.078 |

0.913 0.221 |

0.538 0.061 |

0.321 0.087 |

0.469 0.011 |

0.253 0.112 |

| Lung | Mean 1 SD |

0.013 0.000 |

0.017 0.018 |

0.206 0.020 |

0.115 0.027 |

0.093 0.012 |

0.068 0.015 |

0.094 0.013 |

0.071 0.021 |

0.062 0.010 |

| Kidney | Mean 1 SD |

0.033 0.030 |

0.057 0.028 |

0.137 0.021 |

0.074 0.027 |

0.109 0.017 |

0.065 0.013 |

0.039 0.007 |

0.039 0.034 |

0.021 0.010 |

| Stomach | Mean 1 SD |

0.009 0.004 |

0.017 0.003 |

0.404 0.011 |

0.030 0.008 |

0.039 0.017 |

0.038 0.011 |

0.026 0.015 |

0.049 0.021 |

0.036 0.019 |

| Intestine | Mean 1 SD |

0.023 0.010 |

0.099 0.038 |

0.154 0.035 |

0.159 0.063 |

0.292 0.127 |

0.225 0.051 |

0.113 0.031 |

0.176 0.063 |

0.148 0.030 |

| Pancreas | Mean 1 SD |

0.008 0.000 |

0.024 0.002 |

0.125 0.011 |

0.312 0.015 |

0.057 0.024 |

0.051 0.01 |

0.043 0.021 |

0.035 0.012 |

0.055 0.022 |

| Brain | Mean 1 SD |

0.017 0.009 |

0.006 0.011 |

0.028 0.01 |

0.099 0.023 |

0.065 0.024 |

0.033 0.011 |

0.037 0.012 |

0.041 0.021 |

0.024 0.014 |

| Thyroid | Mean 1 SD |

0.016 0.000 |

0.034 0.007 |

0.026 0.011 |

0.044 0.013 |

0.032 0.015 |

0.042 0.021 |

0.032 0.011 |

0.041 0.022 |

0.035 0.013 |

| Testis | Mean 1 SD |

0.022 0.010 |

0.021 0.013 |

0.038 0.022 |

0.021 0.008 |

0.042 0.010 |

0.058 0.031 |

0.029 0.008 |

0.033 0.016 |

0.036 0.011 |

| Bone | Mean 1 SD |

0. 233 0.021 |

0.377 0.035 |

0.369 0.121 |

1.049 0.236 |

1.518 0.049 |

1.081 0.211 |

0.930 0.084 |

0.569 0.308 |

0.656 0.182 |

| Muscle | Mean 1 SD |

0.011 0.000 |

0.035 0.010 |

0.034 0.015 |

0.043 0.017 |

0.052 0.023 |

0.041 0.026 |

0.034 0.017 |

0.029 0.021 |

0.025 0.020 |

ID: injected dose. 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 48, and 64 d were time at which animals were anesthetized and sacrificed, blood was collected, tissues were weighed, and radioactivity was quantified. n = 5 mice at each time point.

Table 2.

Biodistribution of 32P-CP particle in nude mice bearing U87MG glioma after intratumor injection of 32P-CP colloids (n = 5).

| Tissue | Radioactivity distribution (%ID/g) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 d | 1 d | 2 d | 4 d | 8 d | 16 d | 32 d | 48 d | 64 d | ||

| Tumor | Mean 1 SD |

429.1 110.2 |

455.60 265.72 |

570.5 159.4 |

470.76 218.05 |

525.57 52.21 |

676.25 61.15 |

—— | —— | —— |

| Blood | Mean 1 SD |

0.057 0.021 |

0.073 0.035 |

0.079 0.010 |

0.046 0.011 |

0.022 0.047 |

0.048 0.014 |

0.02 0.011 |

0.079 0.014 |

0.070 0.012 |

| Heart | Mean 1 SD |

0.171 0.052 |

0.124 0.013 |

0.232 0.151 |

0.207 0.105 |

0.148 0.049 |

0.097 0.054 |

0.009 0.035 |

0.246 0.113 |

0.183 0.071 |

| Liver | Mean 1 SD |

0.253 0.110 |

0.146 1.077 |

1.690 0.745 |

1.656 1.076 |

2.918 0.076 |

1.219 0.171 |

1.122 2.037 |

2.629 0.041 |

2.465 0.016 |

| Spleen | Mean 1 SD |

0.324 0.197 |

0.249 0.128 |

0.559 0.121 |

1.241 0.052 |

0.913 0.021 |

0.769 0.061 |

0.334 0.087 |

0.469 0.011 |

0.356 0.019 |

| Lung | Mean 1 SD |

0.233 0.103 |

0.163 0.018 |

0.239 0.078 |

0.256 0.127 |

0.433 0.212 |

0.512 0.015 |

0.222 0.013 |

0.041 0.021 |

0.052 0.010 |

| Kidney | Mean 1 SD |

0.192 0.074 |

0.153 0.028 |

0.269 0.121 |

0.256 0.127 |

0.019 0.017 |

0.071 0.092 |

0.210 0.007 |

0.269 0.034 |

0.056 0.019 |

| Stomach | Mean 1 SD |

0.056 0.034 |

0.097 0.003 |

0.016 0.011 |

0.033 0.008 |

0.019 0.017 |

0.113 0.011 |

0.241 0.015 |

0.049 0.021 |

0.036 0.019 |

| Intestine | Mean 1 SD |

0.203 0.109 |

0.038 0.012 |

0.154 0.035 |

0.159 0.063 |

0.156 0.127 |

0.136 0.051 |

0.408 0.031 |

0.176 0.063 |

0.248 0.030 |

| Pancreas | Mean 1 SD |

0.030 0.024 |

0.101 0.002 |

0.049 0.011 |

0.074 0.015 |

0.077 0.024 |

0.182 0.01 |

0.020 0.021 |

0.035 0.012 |

0.055 0.022 |

| Brain | Mean 1 SD |

0.017 0.019 |

0.026 0.021 |

0.011 0.010 |

0.036 0.023 |

0.024 0.014 |

0.013 0.011 |

0.008 0.012 |

0.013 0.021 |

0.024 0.014 |

| Thyroid | Mean 1 SD |

0.016 0.021 |

0.077 0.007 |

0.026 0.011 |

0.044 0.013 |

0.026 0.015 |

0.022 0.021 |

0.012 0.011 |

0.021 0.022 |

0.035 0.013 |

| Testis | Mean 1 SD |

0.022 0.012 |

0.041 0.013 |

0.038 0.022 |

0.021 0.008 |

0.042 0.010 |

0.018 0.031 |

0.029 0.008 |

0.033 0.016 |

0.036 0.011 |

| Bone | Mean 1 SD |

0.762 0.421 |

2.343 0.035 |

2.369 0.121 |

3.856 0.236 |

4.004 1.093 |

3.541 0.211 |

2.605 0.084 |

2.869 0.308 |

2.656 0.182 |

| Muscle | Mean 1 SD |

0.007 0.003 |

0.083 0.010 |

0.034 0.015 |

0.043 0.017 |

0.046 0.023 |

0.092 0.026 |

0.053 0.017 |

0.049 0.021 |

0.045 0.020 |

ID: injected dose. 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 48, and 64 d were time at which animals were anesthetized and sacrificed, blood was collected, tissues were weighed, and radioactivity was quantified. n = 5 mice at each time point.

Figure 2.

Bar graphs of the peak uptake of 32P-CP in important organs after intratumour administration of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds and 32P-CP colloids (∗∗ indicates P < 0.01, ∗ indicates P < 0.05, and # indicates P > 0.05).

3.3. Radioactivity Gradient Developed in Tumour and Surrounding Tissues

Figure 3 demonstrated the distribution of the released 32P-CP particles in tumour and adjacent normal tissues in the CG or SG after eradication and radioactivity counting of the remaining 32P-CP-PLGA seeds. Most of released 32P-CP particles in the SG were stagnant in the tumour core with a decreasing gradient towards the periphery in the SG (Figure 3(b)). This finding was confirmed by using SEM (Figure 3(c)). The gradient existed for approximately 2 weeks and became insignificant on day 14. The %ID/g tumour uptake of 32P-CP significantly increased on day 16, primarily reflecting tumour shrinkage. Conversely, the intratumour distribution of 32P-CP in the CG was irregular and a slight increase of %ID/g tumour uptake was observed with tumour shrinkage. The regional peak uptake in tumour tissues (t2) on day 16 was higher than day 8 (t1) (Figure 3(a)).

Figure 3.

Bar graphs and SEM results of 32P-CP distribution in tumour and adjacent normal tissues at different time points after the intratumoural administration of SG and CG. (a) 32P-CP distribution in tumour and adjacent normal tissues at different time points in CG. The regional peak uptake in tumour tissues (t2) on day 16 was higher than day 8 (t1) (# means P < 0.05) [t1, t2, and t3 indicate tumour tissues at different distance from the seed (SG) or the core of the tumour (CG), near to far, and “s” indicates tissues surrounding the tumour]. (b) 32P-CP distribution in tumour and adjacent normal tissues in the SG (significant difference between ti and t2, t2 and t3, and t3 and s, P < 0.05) (c). SEM results of tumour and adjacent normal tissues (t1, t2, t3, and s). The 32P-CP particles are indicated with a black arrow. Irregularity of radioactivity distribution can be observed in the tumour and adjacent tissues in the CG, while a radioactivity gradient formed in the SG. The results were confirmed by SEM.

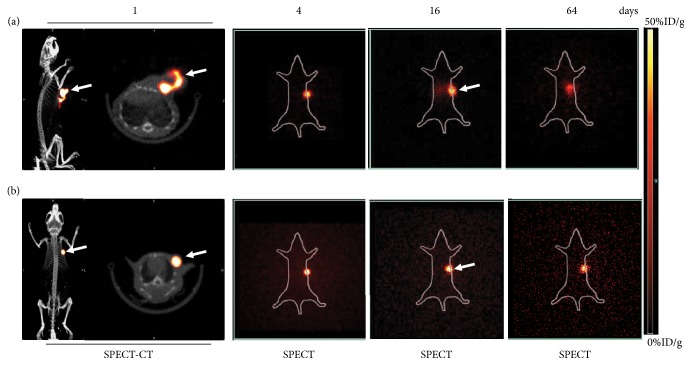

Micro-SPECT/CT Imaging. 32P bremsstrahlung facilitates SPECT-CT imaging to monitor the intratumour administration of 32P-CP colloid (Figure 4(a)) and 32P-CP-PLGA seeds (Figure 4(b)). As shown in Figure 4(b), 32P-CP-PLGA seeds showed dot-like focal radioactivity accumulation on days 1 and 4. The released 32P-CP showed a vague appearance of tumour on days 16 and 64 in the SG. 32P-CP colloids displayed irregular shapes in and/or close to the tumour location, with abnormal distribution in the liver in the CG on day 16, and this effect was even more apparent on day 64. The T/Tmk decreased to 89.3% ± 2.4% (SG) and 65.8% ± 3.1% (CG) on day 64 based on micro-SPECT/CT images.

Figure 4.

Representative micro-SPECT/CT or micro-SPECT images in the SG and CG. Micro-SPECT/CT images on day 1 and micro-SPECT images on days 4, 16, and 64 were obtained after intratumoural injection of colloidal 32P-CP ((a) 32P-CP colloids were in irregular shapes with leak from injection site and much notable abnormal distribution and liver appearance) and intratumour implantation of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds ((b) 32P-CP-PLGA seeds demonstrated the shape of a dot. No significant difference or appearance of other organs was observed until 64 days). The white arrows refer to tumors.

3.4. 68Ga-3PRGD2 Micro-PET/CT Imaging and Tumour Growth Monitoring

As shown in Figure 5, the tumour uptake heterogeneity of 68Ga-3PRGD2 was observed on days 2 and 4 with internal absence on day 8. Scar formation was observed on day 16 in the SG. In the P-CP-PLGA seed group, the distribution of 68Ga-3PRGD2 was uniform for 8 day(s), and internal heterogeneity was observed on day 8, reflecting natural necrosis. The tumour uptake (%ID/cm3) of 68Ga-3PRGD2 in the SG (8.50 ± 1.32) was higher than that in the P-CP-PLGA group (7.15 ± 1.49, p < 0.05) on day 0.5, while the tumour uptake in the SG (5.13 ± 1.06) was lower than that in the P-CP-PLGA group (8.16 ± 1.26, p < 0.01) on day 2. The tumour time-growth curve displayed no significant changes during 10 days in the SG or CG after 32P administration, and 40% (2/5) of the mice demonstrated tumour growth near the scar on day 20.

Figure 5.

68Ga-3PRGD2 micro-PET-CT imaging during 32P brachytherapy and tumour volume measurement using a caliper. (a) The 68Ga-3PRGD2 micro-PET/CT transverse images of nude mice bearing glioma on days 0.5, 2, 4, 8, and 16 after intratumoural implantation of radioactive 32P-CP-PLGA seeds (A) and nonradioactive P-CP-PLGA seeds (B). (b) Tumour volume was measured using a caliper every other day after intratumoural administration of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds, 32P-CP colloid, and nonradioactive P-CP-PLGA seed. (c) Tumour uptake of 68Ga-3PRGD2 was quantified based on micro-PET/CT imaging and compared between radioactive and nonradioactive seeds group. Tumour uptake (%ID/g) of 68Ga-3PRGD2 was significantly different at the same points. In 32P-CP-PLGA seeds group, distribution heterogeneity of 68Ga-3PRGD2 was observed on day 2 and was even significant and toroidal on day 4, with slight accumulation of radiotracer on day 8 and being almost negative on day 16. The distribution of 68Ga-3PRGD2 was uniform at 8 days after nonradioactive seed implantation. Internal absence was observed on day 16, reflecting ulcer formation. # means tumour uptake of 68Ga-3PRGD2 in P-CP-PLGA seeds group was significantly lower than 32P-CP-PLGA seeds group (P < 0.05) while ∗ means tumour uptake of 68Ga-3PRGD2 in P-CP-PLGA seeds group was significantly higher than 32P-CP-PLGA seeds group (P < 0.05). The white arrows refer to tumors.

3.5. Immunohistochemistry Examination

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to examine the αvβ3 and CD31 expression levels in tumour tissues from the xenografted gliomas in the SG and P-CP-PLGA group on days 0.5, 2, and 4; as shown in Figure 6, compared with the P-CP-PLGA seed group, the quantitation of the glioma anti-αvβ3 immunofluorescence levels in the SG revealed a 1.37-fold (±0.15) mean increase (±SD) on day 0.5 and 0.74-fold (±0.22) and 0.15-fold (±0.05) decreases on days 2 and 4, respectively. IHC examination was not performed on days 8 and 16 due to increased areas of necrosis and scar formation.

Figure 6.

Representative immunohistochemical images for frozen glioma slices from xenografted glioma tumours at different time points (day 0.5: (a, b); day 2: (c, d); day 4: (e, f)) after intratumoural implantation of radioactive 32P-CP-PLGA seeds (a, c, e) and nonradioactive P-CP-PLGA seeds (b, d, f). The CD31 was used to label the tumour endothelial cells on blood vessels. The integrin β3 was visualized with Cy3 (red), and CD31 was visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (green) under an Olympus fluorescence system, scale bar: 50 μm.

4. Discussion

32P-CP-PLGA seed is a biodegradable dosage form of 32P, utilizing PLGA as the controlled release carrier for drug delivery. In addition to its easy preparation in large amounts, the main advantage of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds is their delivery of high-dose radiation to the tumour and long intratumoural radioactive effective half-life with minimal distribution and damage to systemic tissues. A radioactivity gradient formed inside the tumour with potential effect to enhance the intratumour fire effect, reduce damage to adjacent tissues, and avoid the implantation of low radioactivity seeds in the peripheral part of the tumours.

No significant difference was observed in tumour uptake of 32P-CP particles in the SG and CG immediately after administration, except for the occurrence of leakage of colloidal 32P-CP in the CG. However, the dynamic radioactivity distribution indicated more retention and longer effective half-life of 32P-CP in the tumour and less or even undetectable distribution in other tissues in the SG compared with that in the CG. The principal mechanism likely involved the arrest of 32P-CP particles inside the seeds using the framework of PLGA, and their release and slow drainage was determined by the biodegradation of PLGA. A radioactivity concentration gradient, formed by the 32P-CP particles released from the 32P-CP-PLGA seeds, was observed inside the tumour. The tumour uptake (%ID/g) was extremely high, primarily because more than 95% (%ID) of the implanted 32P remained in the small tumour tissues (approximately 0.2 cm3) during the first few days. The increased uptake primarily reflected tumour shrinkage on day 16 and scar formation. The released 32P-CP particles increase the killing range and enhance the therapeutic effect without noticeable damage to adjacent tissues. The gradient gap was predominant in the first few days and narrowed with increasing release of 32P-CP particles and tumour shrinkage. However, the irregular and uneven intratumour distribution of 32P-CP colloids in the CG led to a therapeutic blind area, tumour relapse, and leakage from the injection site, resulting in damage to the adjacent tissues.

The 32P-CP particles drained from the tumour were primarily distributed throughout reticuloendothelial systems, such as the liver in the CG, and were less than reported [9]. This effect potentially reflects the use of gelatine sponge to prevent or reduce the leakage of 32P-CP colloids. The uptake of 32P-CP particles in normal tissues peaked at 16 days and likely involved the following three mechanisms. First, 32P-CP particles at the surface or inlaying the outer 1/3 of the seeds tended to be released, while those inlaid near the core stagnated inside, although there was gradual formation of tunnels and cavities. Second, the decrease or lack of regional circulation around the seeds resulting from tumour tissue necrosis and scar formation may inhibit the drainage of released 32P-CP particles. Third, the experimental period used in the present study may not be long enough. Pathological changes of important organs were absent in the SG.

32P bremsstrahlung SPECT imaging facilitates the positioning, effective for half-life evaluation under physical conditions [21]. Any immigration or abnormal uptake can easily be detected, and SPECT-CT fusion techniques with a certain postprocessing attenuation correction algorithm may contribute to precise localization, dosiology studies, and future establishment of brachytherapy in clinical settings [6].

18F-FDG PET-CT imaging was widely used to monitor therapeutic effect of tumour treatment. However, two potential disadvantages limit its use in gliomas. One disadvantage is the high distribution of glioma in normal brain tissues, particularly in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, and thalamus, where glioma is prone to occur. The other disadvantage is the increased accumulation of tumour tissue when inflammatory cells, such as macrophages, are present, particularly at the early stages of treatment [19]. 18F-FPPRGD2 is superior to 18F-FDG because the uptake of 18F-FPPRGD2 is not influenced by tumour-associated macrophages after chemotherapy, and the remarkable distribution of 68Ga-3PRGD2 in the U87MG xenografts is observed with low background in the normal brain tissues compared with 18F-FDG [17, 19]. 68Ga is easily accessible from a 68Ge-68Ga generator and showed similar labelling characteristics with therapeutic isotopes, such as 177Lu, with DOTA and NOTA as linkers. In the present study, the initial increased uptake of 68Ga-3PRGD2 in glioma was observed on day 0.5 after 32P-CP-PLGA seed implantation. The possible mechanism involves the rapid upregulation of integrin expression induced by a low-to-intermediate dose of radiation, as previously reported [22]. Thus, the increased glioma uptake of 68Ga-3PRGD2 on day 0.5 in the SG is possibly due to radiation, while the decrease on day 2 is due to cell damage resulting from accumulated 32P radiation and therapeutic effects [23]. This effect occurred much earlier than the tumour volume reduction and was confirmed using IHC. 68Ga-3PRGD2 imaging has potential to serve as an important tool for the therapeutic evaluation of 32P brachytherapy of glioma as early as day 2. Thus, the precise relationship between the β− radiation dose and integrin expression upregulation needs further study.

5. Conclusions

32P-CP-PLGA seeds, controlling the release of entrapped 32P-CP particles, are promising for glioma brachytherapy. 68Ga-3PRGD2 imaging shows potential for early response evaluation of 32P-CP-PLGA seeds brachytherapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by grants from the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2007AA02Z471), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0103201), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81301247, 81501528), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20130082), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Youth Talent (QNRC2016075), and the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (15JCQNJC10600).

Abbreviations

- 32P:

Phosphorus-32

- 68Ga:

Gallium-68

- 18F:

Fluorine-18

- CT:

Computed tomography

- PET:

Positron emission tomography

- SPECT:

Single photon emission computed tomography

- 32P-CP:

32P-chromic phosphate

- 32P-CP-PLGA:

32P-chromic phosphate-polylactide-co-glycolide

- %ID/g:

Percent injected dose per gram

- FDG:

Fludeoxyglucose.

Disclosure

Guoqiang Shao, Yuebing Wang, and Xianzhong Liu are co-first authors. An earlier version of this work was presented as an abstract at MTAI: Educational Exhibits Posters 2017.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Guoqiang Shao, Yuebing Wang, Xianzhong Liu, Meili Zhao, Jinhua Song, Peiling Huang, Feng Wang, and Zizheng Wang participated in the study design, execution, and analysis, manuscript drafting, and critical discussions. Guoqiang Shao, Yuebing Wang, and Xianzhong Liu have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Plate K. H., Scholz A., Dumont D. J. Tumor angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic therapy in malignant gliomas revisited. 2012;124(6):763–775. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruge M. I., Kickingereder P., Grau S., et al. Stereotactic iodine-125 brachytherapy for the treatment of WHO grades II and III gliomas located in the central sulcus region. 2013;15(12):1721–1731. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salgueiro M. J., Duran H., Palmieri M., et al. Bioevaluation of 32P patch designed for the treatment of skin diseases. 2008;35(2):233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marr B. P., Abramson D. H., Cohen G. N., Williamson M. J., McCormick B., Barker C. A. Intraoperative high-dose rate of radioactive phosphorus 32 brachytherapy for diffuse recalcitrant conjunctival neoplasms: A retrospective case series and report of toxicity. 2015;133(3):283–289. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.5079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folkert M. R., Bilsky M. H., Cohen G. N., et al. Intraoperative 32P high-dose rate brachytherapy of the dura for recurrent primary and metastatic intracranial and spinal tumors. 2012;71(5):1003–1010. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31826d5ac1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denis-Bacelar A. M., Romanchikova M., Chittenden S., et al. Patient-specific dosimetry for intracavitary 32P-chromic phosphate colloid therapy of cystic brain tumours. 2013;40(10):1532–1541. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2451-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alimi K. A., Firusian N., Dempke W. Effects of intralesional 32-P chromic phosphate in refractory patients with head and neck tumours. 2007;27(4 C):2997–3000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaca Montijo I. J., Khurana V., Alazmi W. M., Order S. E., Barkin J. S. Vascular pancreatic gastric fistula: A complication of colloidal 32P injection for nonresectable pancreatic cancer. 2003;48(9):1758–1759. doi: 10.1023/A:1025447128887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian J. H., Xu B. X., Zhang J. M., Dong B. W., Liang P., Wang X. D. Ultrasound-guided internal radiotherapy using yttrium-90-glass microspheres for liver malignancies, Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication. 1996;37:958–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu G., Hu Q., Feng X., et al. PEG-PLA nanoparticles modified with APTEDB peptide for enhanced anti-angiogenic and anti-glioma therapy. 2014;35(28):8215–8226. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain D., Bajaj A., Athawale R., et al. Surface-coated PLA nanoparticles loaded with temozolomide for improved brain deposition and potential treatment of gliomas: Development, characterization and in vivo studies. 2016;23(3):999–1016. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.926574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong R., Gabrielson N. P., Fan T. M., Cheng J. Polymeric nanomedicines based on poly(lactide) and poly(lactide-co- glycolide) 2012;16(6):323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cossms.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X., Jia R., Xu L., et al. 32P-chromic phosphate-poly(l-Lactide) seeds of sustained release and their brachytherapy for prostate cancer with lymphatic metastasis. 2012;27(7):446–451. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2011.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bala I., Hariharan S., Kumar M. N. V. R. PLGA nanoparticles in drug delivery: the state of the art. 2004;21(5):387–422. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v21.i5.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loo J. S. C., Ooi C. P., Boey F. Y. C. Degradation of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) and poly(L-lactide) (PLLA) by electron beam radiation. 2005;26(12):1359–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D., Zhao X., Zhang L., et al. 68Ga-PRGD2 PET/CT in the evaluation of glioma: A prospective study. 2014;11(11):3923–3929. doi: 10.1021/mp5003224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan D., Zhang X., Zhong L., et al. 68Ga-Labeled 3PRGD2 for Dual PET and Cerenkov Luminescence Imaging of Orthotopic Human Glioblastoma. 2015;26(6):1054–1060. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi J., Jin Z., Liu X., et al. PET imaging of neovascularization with 68Ga-3PRGD2 for assessing tumor early response to endostar antiangiogenic therapy. 2014;11(11):3915–3922. doi: 10.1021/mp5003202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun X., Yan Y., Liu S., et al. 18F-FPPRGD2 and 18F-FDG PET of response to Abraxane therapy. 2011;52(1):140–146. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.080606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao G., Zhou Y., Wang F., Liu S. Monitoring glioma growth and tumor necrosis with the U-SPECT-II/CT scanner by targeting integrin alphavbeta3, Molecular imaging. 2013:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balachandran S., McGuire L., Flanigan S., Shah H., Boyd C. M. Bremsstrahlung imaging after 32P treatment for residual suprasellar cyst. 1985;12(3):215–221. doi: 10.1016/0047-0740(85)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao H., Zeng Z.-Z., Fay K. S., et al. Role of α5β1 integrin up-regulation in radiation-induced invasion by human pancreatic cancer cells. 2011;4(5):282–292. doi: 10.1593/tlo.11133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ning S., Tian J., Marshall D. J., Knox S. J. Anti-αv integrin monoclonal antibody intetumumab enhances the efficacy of radiation therapy and reduces metastasis of human cancer xenografts in nude rats. 2010;70(19):7591–7599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]