Abstract

Aims

To estimate the overall and cause-specific mortality in a population of African-Americans and white Americans with a low socio-economic status who had young-onset insulin-treated diabetes and had survived beyond the age of 40 years, and to examine whether any excess risk varied according to age at diabetes onset.

Methods

Using the Southern Community Cohort Study, we conducted a mortality follow-up of a cohort of mostly low-income participants aged 40–79 years (mean 50 years) at cohort entry with insulin-treated diabetes diagnosed before age 30 years (n=475) and without diabetes (n=62 266). Childhood onset was defined as diabetes diagnosed before age 20 years (n=162), while young-adulthood onset was defined as diabetes diagnosed between ages 20 and 29 years (n=313). Cause-specific mortality was based on both underlying and contributing causes of death, obtained from death certificates. Multivariable Cox analysis was performed.

Results

During follow-up (mean 9.5 years), 38.7% of those with and 12.9% of those without diabetes died. Compared with those without diabetes, increases in mortality rate were generally similar among those with childhood- and young-adulthood-onset diabetes for deaths from: all causes (childhood: hazard ratio 4.3, CI 3.3–5.5; young adulthood: hazard ratio 4.9, CI 4.0–5.8); ischaemic heart disease (childhood: hazard ratio 5.7, CI 3.5–9.4; young adulthood: hazard ratio 7.9, CI 5.6–11.0); heart failure (childhood: hazard ratio 7.3, CI 4.2–12.7; young adulthood: hazard ratio 5.4, CI 3.3–8.9); sepsis (childhood: hazard ratio 10.3, CI 6.1–17.3; young adulthood: hazard ratio 8.8, CI 5.7–13.5); renal failure (childhood: hazard ratio 15.1, CI 8.6–26.5; young adulthood: hazard ratio 18.2, CI 12.3–27.1); respiratory disorders (childhood: hazard ratio 3.9, CI 2.3–6.7; young adulthood: hazard ratio 5.3, CI 3.7–7.7); suicide/homicide/accidents (childhood: hazard ratio 2.3, CI 0.72–7.0; young adulthood: hazard ratio 5.8, CI 3.4–10.2); and cancer (childhood: hazard ratio 2.1, CI 0.98–4.4; young adulthood: hazard ratio 1.2, CI 0.55–2.5).

Conclusions

We observed high excess long-term mortality for all-cause, renal failure, ischemic heart disease and heart failure mortality in African-American and white American people with early-onset insulin-treated diabetes.

Introduction

Mortality rates among people with Type 1 diabetes have consistently been shown to be three to five times higher than in the general population, even among people surviving to middle age [1–6]. Limited information is available on the long-term survival experience of African-Americans with Type 1 diabetes, or on white Americans with Type 1 diabetes in the lowest income strata of the US population. Determining the critical age ranges at diabetes onset that are associated with the greatest rates of end organ complications and the lowest rates of survival can inform targeting of specific treatment practices in that age-diagnosis cohort, both at onset of Type 1 diabetes and the critical years that follow. However, people diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes and those surviving to middle age may provide unique information on how age at diagnosis affects survival patterns in long-term survivors. Additionally, how age of onset of Type 1 diabetes may affect survival in non-white people and populations with limited education, income and access to healthcare can inform targeted education, risk factor management and treatment practices. We therefore investigated all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a population of African-American and white American people with low socio-economic status (SES) who had survived to age 40 years, and also whether any excess risk varied by age at Type 1 diabetes onset.

Methods

The Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) is a population-based study that was designed to investigate causes of health disparities in the incidence and mortality of cancer and other chronic diseases. Details of the rationale, study design and methods have been described previously [7]. Briefly, between 2002 and 2009, >85 000 participants, aged 40–79 years, were recruited from community health centres (85%) and their surrounding communities (15%) from 12 states in southeastern USA. Community health centres are government-funded healthcare facilities offering basic healthcare services to the medically underserved. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Meharry Medical College.

After obtaining informed consent, information on medical history, lifestyle and demographic factors was collected by in-person interview from community health centre-recruited participants and by completion of the study questionnaire in the postal survey-recruited participants. If a participant answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes or high blood sugar?’, he/she was asked questions about age at diabetes diagnosis and medications currently taken to treat diabetes. Women were asked to exclude gestational diabetes in their reporting. A total of 17 750 individuals reported having a physician diagnosis of diabetes, of whom 421 had a missing age of diabetes diagnosis. Of the remaining 17 329 participants, 1411 were diagnosed before the age of 30 years (hereafter referred to as ‘young-onset’). Five individuals with young-onset diabetes were excluded from analysis because they reported not knowing whether they were using any diabetes medication (n=2) or had missing information on diabetes medication use (n=3). Among those diagnosed with young-onset diabetes, 475 reported using insulin as the only hypoglycaemic agent at the time of enrolment into the SCCS, 242 reported using insulin plus an additional hypoglycaemic agent, and 633 reported not being on insulin therapy. The 475 participants diagnosed with diabetes before the age of 30 years and reporting insulin as their only form of anti-hyperglycaemic therapy at study enrolment formed the basis of our ‘presumed Type 1 diabetes’ cohort, hereafter referred to as ‘Type 1 diabetes’. Of these, 162 were diagnosed before the age of 20 years and formed our childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes cohort and 313 were diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 29 years and formed our young-adulthood-onset cohort. Those reporting no history of physician-diagnosed diabetes at time of enrolment into the SCCS formed our reference population (n=65 266).

Mortality status and underlying and contributing causes of death were determined from linkages of the SCCS population with the National Death Index database, with mortality censored on 31 December 2014. As data relying only on the underlying causes of death listed on death certificates may substantially underestimate the impact of diabetes-related complications on total mortality in individuals with diabetes, we used both the underlying and contributing causes listed on the death certificates in determining cause-specific mortality [8,9]. The specific causes of death investigated were ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, renal disease, respiratory failure/arrest (respiratory disorders), sepsis, accidents and cancer. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th revision codes that were listed as either the underlying or contributing cause of death and were used to define the above disease classifications can be found in the online Supporting Information (Table S1).

The t-test and general linear models were used to test for differences in continuous variables across the comparison groups and chi-squared tests were used to test for differences in categorical data. Cox proportional hazards modelling, using age as the time scale, was used to estimate hazard ratios for all-cause and cause-specific mortality by diabetes age at onset group (childhood, young-adulthood) relative to those without diabetes. The multivariate model included a term for self-reported race in addition to terms for diabetes group, sex, education, annual household income, history of ischaemic heart disease, history of stroke/transient ischaemic attack, history of smoking, and baseline health insurance coverage. Because of sample size limitations in other racial/ethnic groups, effect modification by race was assessed and race-specific analyses conducted among African-American and white American people only. The criterion for statistical significance was a two-tailed P value of < 0.10 for multiplicative interaction, and <0.05 otherwise. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The characteristics of the study participants according to Type 1 diabetes status are shown in Table 1. Compared to those without diabetes, those with Type 1 diabetes were slightly younger, more likely to be female, and had a much higher prevalence of comorbidities, despite having a lower prevalence of history of smoking. Those with Type 1 diabetes were also more likely to have a household annual income of <$15,000 per year, although only those with childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes were more likely to have a lower than high school education level. Characteristics of the study participants with Type 1 diabetes, stratified by age at onset and race, are shown in Table S2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Southern Community Cohort Study ‘Type 1 diabetes’ cohort, stratified by age at diabetes diagnosis

| Childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes N=162 |

Young-adulthood-onset Type 1 diabetes N=313 |

No diabetes N=65 266 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, years | 50.2 ± 7.9* | 49.7 ±7.1‡ | 51.6 ± 8.6 |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 12.6 ± 5.7 | 25.0 ± 2.9 | |

| Diabetes duration, years | 37.5 ± 9.6 | 24.7 ± 7.5 | |

| Sex: female, n (%) | 69.1 (112)† | 64.9 (203)* | 57.9 (37 790) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 35.4 (57) | 23.6 (73) | 31.1 (20 168) |

| African-American | 62.1 (100) | 73.9 (229) | 65.0 (42 159) |

| Other races | 2.5 (4) | 2.6 (8) | 3.9 (2552) |

| Median (IQR) BMI at age 21 years, kg/m2 | 24.1 (21.3–28.1)§ | 24.9 (21.5–28.8)§ | 22.1 (19.3–24.8) |

| Median (IQR) BMI at study baseline, kg/m2 | 30.1 (25.3–36.3)† | 31.0 (26.4–36.4)§ | 28.1 (24.3–32.9) |

| Prior ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 24.8 (40)§ | 18.5 (58)§ | 5.2 (3418) |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 19.3 (31)§ | 12.1 (38)§ | 5.3 (3443) |

| Cataracts, n (%) | 30.4 (49)§ | 19.0 (59)§ | 7.2 (4666) |

| Glaucoma, n (%) | 11.8 (19)§ | 10.6 (33)§ | 2.8 (1816) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 64.8 (105)§ | 78.9 (247)§ | 48.1 (31 395) |

| High cholesterol, n (%) | 48.8 (79)§ | 53.5 (167)§ | 27.9 (18 188) |

| Ever smoker, n (%) | 58.8 (94) | 52.6 (164)§ | 65.3 (42 254) |

| Annual household income**, n (%) | |||

| <$15,000 | 71.3 (114) | 66.8 (207) | 53.4 (34 322) |

| $15,000–$24,999 | 13.1 (21) | 21.3 (66) | 21.2 (13 644) |

| $25,000–$49,000 | 8.8 (14) | 8.1 (25) | 14.7 (9438) |

| ≥$50,000 | 6.9 (11) | 3.9 (12) | 10.7 (6889) |

| Education <12 years | 11.2 (18)* | 8.4 (26) | 7.0 (4544) |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001 and

P<0.0001 compared with those without diabetes.

Table probability for differences in race category <0.05.

Table probability for differences in income category <0.0001.

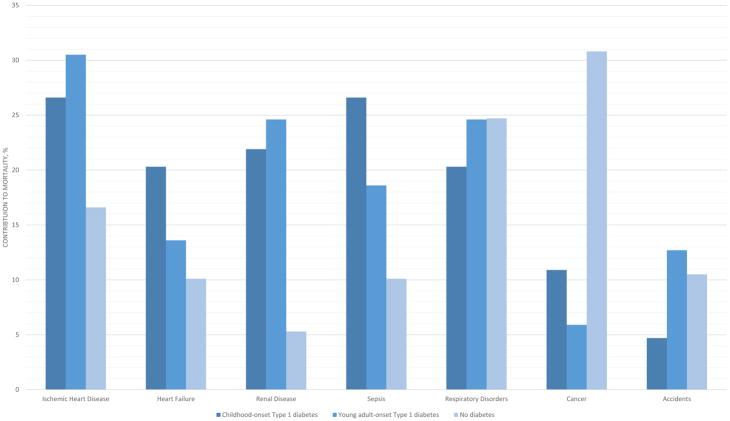

Participants were followed for a mean of 9.5 years, with 8603 deaths recorded. Cumulative mortality was 39.5% (n=64) among those with childhood-onset diabetes, 38.3% (n=120) among those with young-adult-onset diabetes, and 12.9% (n=8419) among those without diabetes. Figure 1 shows the contribution to mortality, stratified by diabetes group, of each of the major causes of death in diabetes. Ischaemic heart disease and renal disease contributed to the greatest number of deaths among those with young-adulthood-onset diabetes, while heart failure and renal disease contributed to the greatest number of deaths among those with childhood-onset diabetes. Accidents accounted for a greater percentage of deaths among those diagnosed with diabetes in their 20s than among those diagnosed in childhood or those without diabetes. Cancer accounted for >30% of all deaths among those without diabetes. By contrast, cancer contributed to ~10% of all deaths in those with childhood-onset diabetes and to only ~5% of all deaths among those with young-adulthood-onset diabetes.

FIGURE 1.

Contribution to mortality of each of the major contributing causes of death in Type 1 diabetes. Mortality event numbers by diabetes onset were as follows: ischaemic heart disease: childhood onset n=17, young adulthood onset n=36, no diabetes n=1380; heart failure: childhood onset n=13, young adulthhood onset n=16, no diabetes n=843; renal disease: childhood onset n=14, young adulthood onset n=29, no diabetes n=438; sepsis: childhood onset n=17, young adulthood onset n=22, no diabetes n=841; respiratory disorders: childhood onset n=13, young adulthood onset n=29, no diabetes n=2053; cancer: childhood onset n=7, young adulthood onset n=7, no diabetes n=2569; accidents: childhood onset n=3, young adulthood onset n=15, no diabetes n=871.

Absolute mortality rates, adjusted for age, for all-cause mortality and each of the major causes of death in Type 1 diabetes are presented in Table 2. Overall, mortality rates were highest for respiratory disorders, followed by ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, sepsis and renal disorders. The mortality rates tended to be higher among white Americans than African-Americans, except for sepsis, but differences between childhood- and young-adulthood-onset groups were not notable, except for heart failure, for which rates were higher among childhood-onset cases.

Table 2.

Age-adjusted mortality rates per 10 000 person-years

| All-cause | Ischaemic heart disease | Heart failure | Renal disease | Respiratory disorders | Sepsis | Cancer | Accidents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes | ||||||||

| African-American | 550.36 | 104.60 | 135.54 | 135.01 | 78.87 | 126.20 | 58.08 | 43.96 |

| White | 763.17 | 190.26 | 335.47 | 150.72 | 378.82 | 145.78 | 70.99 | 0 |

| Young-adulthood-onset Type 1 diabetes | ||||||||

| African-American | 550.98 | 141.00 | 66.34 | 122.09 | 117.94 | 203.10 | 5.29 | 158.87 |

| White | 699.30 | 156.93 | 70.61 | 141.21 | 106.20 | 74.08 | 111.00 | 71.36 |

| No diabetes | ||||||||

| African-American | 140.80 | 21.47 | 15.54 | 9.20 | 31.35 | 15.33 | 45.18 | 11.98 |

| White | 159.57 | 30.78 | 14.63 | 4.37 | 51.57 | 13.09 | 44.82 | 21.26 |

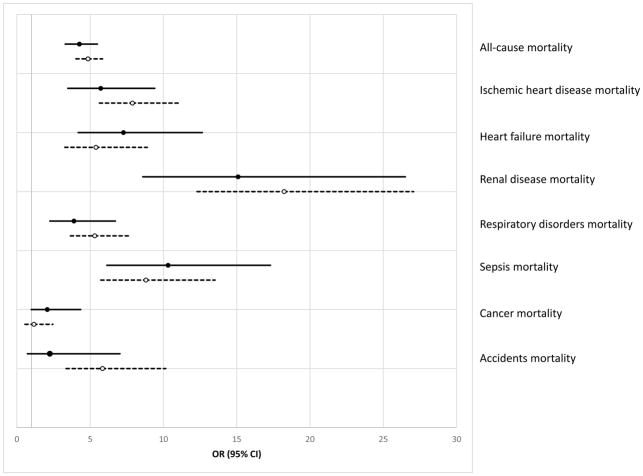

Multivariable adjusted relative mortality rates among adults with Type 1 diabetes compared with those without diabetes are shown in Fig. 2. Although mortality rates, ranging from four- to 18-fold higher, were generally similar among those with childhood-onset and young-adulthood-onset Type 1 diabetes vs those without diabetes, mortality rates were slightly higher for all causes, ischaemic heart disease, renal disorders, respiratory disorders and accidents among those with young-adulthood-onset Type 1 diabetes. Mortality rates were slightly higher for heart failure, sepsis and cancer among those with childhood-onset diabetes.

FIGURE 2.

Multivariable adjusted risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality for Type 1 diabetes compared with those without diabetes, odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI. Solid black lines= childhood onset Type 1 diabetes. Dashed lines = young-adulthood-onset Type 1 diabetes. Multivariable analyses additionally controlled for sex, race, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, prior ischaemic heart disease, prior stroke/transient ichaemic attack, history of smoking, education, annual household income and health insurance coverage.

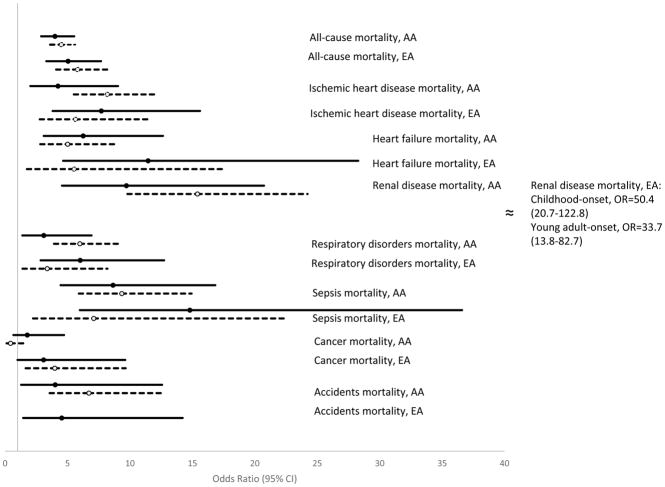

When stratified by race, hazard ratios for all-cause and cause-specific mortality between those with and without diabetes were generally slightly higher among those with young-adulthood-onset Type 1 diabetes among African-American people, but slightly higher for those with childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes among white American people (Fig. 3). This was particularly noticeable for renal failure mortality (race × age at diagnosis group interaction P =0.005). African-American people with childhood-onset diabetes had a 10 times greater risk of mortality from renal failure than African-American people without diabetes, whereas for African-Americans diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in their 20s this excess risk was 15-fold. For white Americans with childhood-onset diabetes, the risk of renal failure mortality was 50 times greater than for white Americans without diabetes. White Americans diagnosed with diabetes in their 20s were at a 34-fold greater risk than white Americans without diabetes. Multivariable adjusted relative mortality rates, stratified by race, between adults with Type 1 diabetes and those without diabetes are shown in Fig. 3.

FIGURE 3.

Multivariable adjusted risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality for Type 1 diabetes compared with those without diabetes stratified by race, odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI. Solid black lines= childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes. Dashed lines = young-adulthood-onset Type 1 diabetes. Multivariable analyses additionally controlled for sex, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension, prior ischaemic heart disease, prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack, history of smoking, education, annual household income and health insurance coverage. P value for race × age at diabetes diagnosis interaction term=0.005 for renal disease mortality. P value for race × age at diabetes diagnosis interaction term=0.007 for cancer mortality. AA, xxx; EA,.

Discussion

Limited information is available on the long-term survival experience of African-American people with Type 1 diabetes, or on white American people with Type 1 diabetes in the lowest income strata of the US population. We observed high excess all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates in our Type 1 diabetes cohort compared with people without diabetes who had a similarly low SES. Race- and age-specific analyses showed that this was true among both African-Americans and white Americans and whether diagnosed with diabetes in childhood or young adulthood. Renal failure and heart failure mortality were common, with rates of mortality from renal failure up to 21 and 61 times higher, respectively, among African-Americans with young-adult onset and white Americans with childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes compared with their counterparts without diabetes with similarly low SES.

Reports on all-cause mortality among African-Americans with Type 1 diabetes have come from the New Jersey 725 cohort [10], the United States Virgin Islands Type 1 (USVT1) diabetes registry cohort [11], and the Allegheny County, Pennsylvania registry of childhood-onset Type 1 diabetes [6]. In the three cohorts, mortality rates were ~6–20 times higher than in the general population. While these excess rates were higher than the excess rate observed in the present study population, our cohort was substantially older and had a longer duration of diabetes when follow-up was initiated. The marked acceleration of mortality starting in middle age in the background population probably attenuated excess mortality rates attributable to Type 1 diabetes in the present study population, which was a survival population, with entry into the SCCS starting at age 40 years. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to report on the survival experience, or more specifically, cause-specific mortality of African-American people with presumed Type 1 diabetes who have lived to at least middle-adulthood. Our data suggest that, for individuals diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in childhood or young adulthood, mortality rates surge in middle age.

Overall, the survival experience of African-Americans and white Americans in our population with presumed Type 1 diabetes was similar for all-cause, ischaemic heart disease, and renal disorders mortality for each of the four age-at-diabetes-onset and race groups. This is in contrast to the much higher rates for these outcomes among African-American people in the Allegheny County registry [12]. We believe the differences observed between these two studies are attributable to the greater differential in SES between African-Americans in the Allegheny cohort than those in the SCCS cohort. The majority of the SCCS cohort was recruited from federally qualified health centres and thus both African-American and white people had similarly low SES. By contrast, no such restrictions were made on the Allegheny County registry population which reflected the background population in which white people generally have a much higher SES than African-American people. Among people with Type 1 diabetes, low SES has been shown to increase the risk of all-cause mortality [13,14] and mortality from cardiovascular disease [14] 2.5- to 3.5-fold.

Ischaemic heart disease was the leading contributor to mortality in the people with Type 1 diabetes in the present study, contributing to ~30% of all deaths (vs 17% in those without diabetes), with hazard ratios six to eight times higher among those with Type 1 diabetes than in those without, findings in line with other reports in Type 1 diabetes [12,15]; however, although ischaemic heart disease was the leading contributor to mortality in our population with Type 1 diabetes, renal failure accounted for the greatest relative increases in mortality compared with the SCCS general population. We observed rates 10- to 15-fold higher among African-American people and 30- to 50-fold higher among white American people compared with the race-specific SCCS general population, consistent with the 100-fold increases in renal disease mortality rates at younger ages observed in the Allegheny County registry study [16]. Another important finding of the present study was that absolute mortality rates to which renal disease was a contributor were essentially similar in African-American and white American people with Type 1 diabetes, suggesting that Type 1 diabetes levels the playing field with regard to the impact of renal disease for African-Americans and white Americans.

We did not find marked differences in mortality outcomes according to age at diabetes diagnosis; mortality rates were essentially similar in the two age-at-diabetes-diagnosis cohorts, regardless of race. While this may be attributable to left truncation and the resulting survival bias among those diagnosed with diabetes during childhood, i.e. people had to live to age 40 years to enter our study and those diagnosed at a younger age would have had a longer exposure to diabetes, the present data may also suggest that duration of diabetes does not play as strong a role in diabetes complications as commonly thought. Some authors have reported an increased risk of complications-related mortality among those diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in later adolescence and young-adulthood relative to those diagnosed in childhood [17], but this has not been consistently observed [15].

Regardless of the age of diagnosis, there was a very high risk of mortality overall and for most of the specific causes of death. Our findings are consistent with results from most recent population studies in people with Type 1 diabetes [18–20]; however, our results are inconsistent with recent data coming from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) study, in which mortality rates were non-significantly lower in the formerly intensive therapy group while modestly, but significantly, higher in the conventional therapy group compared with the US general population [21]. The discrepancy between the present results and those of the DCCT/EDIC study is probably attributable to the selection criteria used by the DCCT/EDIC study, the much higher than national average SES of that cohort [22], and the very extensive yearly clinical examinations carried out in that study. Nevertheless, the impact of the DCCT/EDIC study results on patient treatment is likely be decreased mortality in future cohorts of African-American and white-American people with Type 1 diabetes who have low incomes.

When the SCCS was first conceived, the low-income segment of the US population had rarely been used in large epidemiology cohort studies. In addition to controlling for racial differences in SES, by focusing on the low-income segment of the US population the study aimed to assess the particular chronic disease health challenges of this population. Little information is available on the low-income segment of the Type 1 diabetes population; a major strength of the present study is its large sample size, which included both African-American and white American people with low incomes. Another strength is the relatively large number of African-Americans with presumed Type 1 diabetes, the largest African-American cohort to date with long duration of early-onset, insulin-treated diabetes. By recruiting predominantly from federally qualified health centres, our African-American and white American participants were more likely to have similar access to healthcare.

Classification of diabetes in our cohort was based on self-report of a physician diagnosis, while classification of diabetes type, specifically Type 1 diabetes, was based on age at diabetes diagnosis and the use of insulin as the only form of anti-hyperglycaemic therapy. A weakness of the present study was the likely less than perfect specificity in our presumed Type 1 diabetes cohort. Our population was diagnosed with diabetes on average in the mid to late 1970s but not recruited to the study until ~30 years later; thus, there is the likelihood of misclassification of diabetes type for some participants. The average BMI around the time of average age of diabetes diagnosis for both our African-American and white American participants was more consistent with a Type 1 than Type 2 diabetes population, nevertheless we cannot not rule out other diabetes types. Another limitation is that cause-specific mortality was based on death certificate data and the study therefore includes the limitations inherent in reliance on non-adjudicated death certificate data [8,23]. Finally, survival bias attributable to left truncation might be viewed as a weakness of the present study because the participants were not followed from age at diabetes diagnosis but had to survive until age 40 years to enter the study. However, the objective of the present study was to describe the mortality experience of people surviving to middle age and beyond with Type 1 diabetes and to investigate whether the age at diabetes diagnosis had any impact on survival.

The SCCS is one of the nation’s largest investments in health disparities research. Even when compared with individuals with similarly low incomes, we observed high excess long-term mortality rates for renal disease, ischaemic heart disease and heart failure in African-American and white American people with early-onset insulin-treated diabetes; this excess risk was particularly striking for African-American people diagnosed in their 20s and for white people diagnosed in childhood. These high excess rates are likely to be greater still when compared with the general US population [5]. Given our observed high morbidity rates, manifested by the high prevalence of diabetes complications and the high mortality rates during the prime adult working years, efforts aimed at minimizing complication rates among people with low incomes with presumed Type 1 diabetes may minimize the burden on the public healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 ICD 10 codes used to determine cause-specific mortality.

Table S2 Baseline characteristics of the SCCS ‘Type 1 Diabetes’ cohort, by race and age at diabetes diagnosis.

What’s new?

Little information is available on the mortality outcomes of African-American and white American people with low incomes who have a long duration of Type 1 diabetes.

The majority of the participants in the present study were recruited from federally qualified health centres, which are government-funded health centres offering basic health services to the poorest population in the USA.

Leading causes of death at age ≥40 years among survivors of early-onset diabetes were ischaemic heart disease and renal disease: mortality rates for these specific outcomes were seven- and 18-fold higher compared with those without diabetes.

A greatly elevated mortality rate during their prime working years persists among low-income African-American and white Americans with Type 1 diabetes.

Little difference in mortality was found between those with childhood-onset vs young-adulthood-onset diabetes, suggesting that diagnosis at any early age conveys elevated long-term risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This work was supported by grant R01-CA-092447 from the National Cancer Institute to Vanderbilt University Medical Center and grant U54 GM104924-02 from the National Institute of General Internal Medicine to the West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute. The funders had no involvement in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation and/or publication decisions.

The authors would like to thank the participants of the SCCS for their dedication and for making this research possible. Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 75th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, New Orleans, Louisiana, June 2016.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

References

- 1.DERI Mortality Study Group. International analysis of insulin-dependent diabetes mortality: a preventative mortality perspective the Diabetes Epidemiology Research International (DERI) Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:612–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skrivarhaug T, Bangstad H-J, Stene LC, Sandvik L, Hanssen K, Joner G. Long-term mortality in a nationwide cohort of childhood-onset type 1 diabetic patients in Norway. Diabetologia. 2006;49:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlquist G, Kallen B. Mortality in Childhood-Onset Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2384–2387. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishimura R, LaPorte R, Dorman J, Tajima N, Becker D, Orchard T. Mortality Trends in Type 1 Diabetes: the Allegheny County (Pennsylvania) Registry 1965–1999. Diabetes Care. 2001;27:398–404. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.5.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway BN, Elasy TA, May ME, Blot WJ. Mortality by race among low-income adults with early-onset insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3107–3112. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Secrest AM, Becker DJ, Kelsey SF, LaPorte RE, Orchard TJ. All-cause mortality trends in a large population-based cohort with long-standing childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: the Allegheny County type 1 diabetes registry. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2573–2579. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. The Southern Community Cohort Study: Investigating health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:26–37. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roper NA, Bilous RW, Kelly WF, Unwn NC, Connolly VM. Cause-Specific Mortality in a Population with Diabetes. South Tees Diabetes Mortality Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:43–48. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson SI, Willis J, Florkowski CM, Scott RS. Cause-specific mortality in insulin-treated diabetic patients: A 20-year follow-up. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;80:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy M, Rendas-Baum R, Skurnick J. Mortality in African-Americans with Type 1 diabetes: The New Jersey 725. Diabet Med. 2006;23:698–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Washington RE, Orchard TJ, Arena VC, LaPorte RE, Secrest AM, Tull ES. All-cause mortality in a population-based type 1 diabetes cohort in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Secrest AM, Becker DJ, Kelsey SF, LaPorte RE, Orchard TJ. Cause-specific mortality trends in a large population-based cohort with long-standing childhood-onset type 1 diabetes. The Allegheny County Type 1 Diabetes Registry. Diabetes. 2010;59:3216–3222. doi: 10.2337/db10-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Secrest AM, Costacou T, Gutelius B, Miller RG, Songer TJ, Orchard TJ. Association of socioeconomic status with mortality in type 1 diabetes: the Pittsburgh epidemiology of diabetes complications study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rawshani A, Svensson AM, Rosengren A, Eliasson B, Gudbjornsdottir S. Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in 24,947 Individuals With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1518–1527. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harjutsalo V, Maric-Bilkan C, Forsblom C, Groop PH. Impact of sex and age at onset of diabetes on mortality from ischemic heart disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:144–148. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Secrest AM, Becker DJ, Kelsey SF, Laporte RE, Orchard TJ. Cause-specific mortality trends in a large population-based cohort with long-standing childhood-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2010;59:3216–3222. doi: 10.2337/db10-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feltbower RG, Bodansky HJ, Patterson CC, Parslow RC, Stephenson CR, Reynolds C, et al. Acute complications and drug misuse are important causes of death for children and young adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the Yorkshire Register of diabetes in children and young adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:922–926. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harding JL, Shaw JE, Peeters A, Guiver T, Davidson S, Magliano DJ. Mortality trends among people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Australia: 1997–2010. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2579–2586. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding JL, Shaw JE, Peeters A, Guiver T, Davidson S, Magliano DJ. Mortality trends among people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Australia: 1997–2010. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2579–2586. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0096. Correction: Diabetes Care 2015;38:733–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secrest AM, Becker DJ, Kelsey SF, LaPorte RE, Orchard TJ. All-cause mortality trends in a large population-based cohort with long-standing childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: the Allegheny County type 1 diabetes registry. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2573–2579. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortality in Type 1 Diabetes in the DCCT/EDIC Versus the General Population. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1378–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson AM, Braffett BH, Cleary PA, Gubitosi-Klug RA, Larkin ME. The long-term effects of type 1 diabetes treatment and complications on health-related quality of life: a 23-year follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications cohort. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3131–3138. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhlhauser I, Sawicki PT, Blank M, Overmann H, Richter B, Berger M. Reliability of causes of death in persons with Type I diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1490–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0957-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 ICD 10 codes used to determine cause-specific mortality.

Table S2 Baseline characteristics of the SCCS ‘Type 1 Diabetes’ cohort, by race and age at diabetes diagnosis.