Abstract

To create an intricately patterned and reproducibly sized and shaped organ, many cellular processes must be tightly regulated. Cell elongation, migration, metabolism, proliferation rates, cell-cell adhesion, planar polarization and junctional contractions all must be coordinated in time and space. Remarkably, a pair of extremely large cell adhesion molecules called Fat (Ft) and Dachsous (Ds), acting largely as a ligand-receptor system, regulate, and likely coordinate, these many diverse processes. Here we describe recent exciting progress on how the Ds-Ft pathway controls these diverse processes, and highlight a few of the many questions remaining as to how these enormous cell adhesion molecules regulate development.

Intro

Fat (Ft) and Dachsous (Ds) are enormous Drosophila protocadherins, with extracellular domains (ECDs) of 34 and 27 cadherin repeats, respectively, and large intracellular domains (ICDs); Ft also has extracellular laminin G and EGF repeats. Recognizable homologs of both are found throughout the metazoa, as are members of a second family of Fat-like proteins known in Drosophila as Fat-like, Ft2 or Kuglei [1] In mammals there is one Ft homolog (FAT4), two Ds homologs (DCHS1 and DCHS2), and three Ft-like homologs (FAT1-3). Drosophila Fat and Ds, like vertebrate FAT4 and DCHS1, show preferentially heterophilic binding, and this activates bi-directional signaling mediated by their ICDs that regulate a number of critical developmental processes. No heterophilic binding partners have yet been identified for Fat-like proteins; we will largely limit our discussion here to the overlapping functions of the Ft/Ds and FAT4/DCHS1 binding pairs.

Fat, Ds and the Hippo pathway

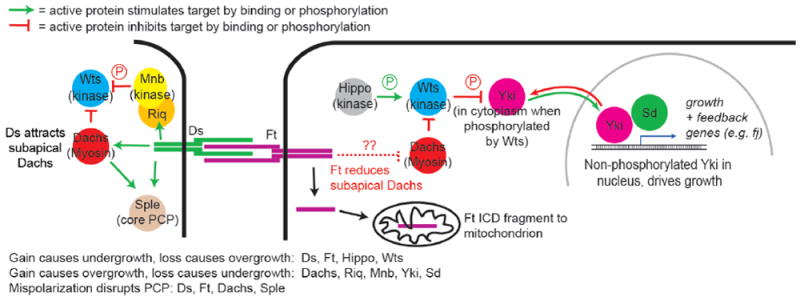

Ft and Ds reduce cell proliferation in a variety of Drosophila tissues; this effect has been most extensively analyzed in the imaginal discs, the precursors of the adult head, thorax and appendages. Ft and Ds prevent disc overgrowth by regulating the well-conserved Hippo pathway (Figure 1; reviewed in [2]). The Hippo pathway core consists of an upstream kinase, Hippo (Hpo) which phosphorylates and activates an NDR family kinase Warts (Wts). Wts in turn phosphorylates the transcriptional co-activator Yorkie (Yki), which sequesters Yki out of the nucleus through interactions with 14-3-3 binding proteins, reducing Yki-driven transcription of pro-growth- and anti-apoptotic genes. A complex web of regulators controls the activities of Hpo, Wts and Yki, and remarkable progress has been made in the past few years linking a subset of these to the activities of Ft and Ds.

Figure 1.

The regulation of Hippo. mitochondrial and PCP activity by the ICDs of Ds and Ft. Details on connections between the Ft ICD and the myosin Dachs are show in Figure 2.

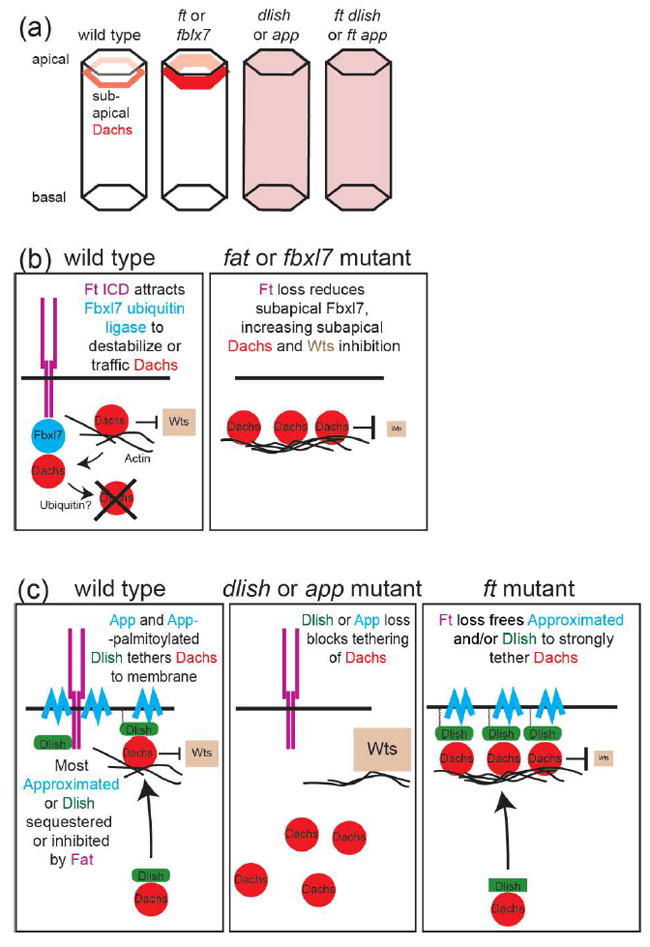

The disc overgrowth observed in ft or ds mutants can be suppressed by Ft’s ICD, and the best-studied effector of the Ft ICD is the unconventional type XX myosin Dachs [3-5]. Loss of Ft or Ds-bound Ft greatly increases the accumulation of Dachs in the subapical domain of epithelial cells, an effect specific for the Ft/Ds branch of the Hippo pathway (Figure 1,2a). The increased Dachs is thought to bind to and inhibit subapical Wts and thereby elicit much or all of the overgrowth of ft or ds mutants. In vivo, Dachs overexpression causes overgrowth (though not as dramatic as loss of ft), while dachs loss blocks ft mutant overgrowth.

Figure 2.

Regulation of Dachs levels and localization by the ICD of Ft. (a) Removal of Ft or Fbxl7 increases Dachs levels in the subapical cell cortex. Removal of Dlish or App reduces Dachs in the subapical cortex and increases cytoplasmic Dachs, even in the absence of Ft. (b) The Ft ICD recruits the F-box ubiquitin ligase to the subapical cell cortex where it reduces Dachs levels, possibly through ubiquination of Dachs or a Dachs binding partner, leading to destabilization of Dachs or trafficking of Dachs away from the cortex. In ft mutants, Dachs levels increase, inhibiting Wts. (c) App and App-palmitoylated Dlish bind and tether Dachs to the subapical cell cortex. Loss of Dlish or App decreases subapical Dachs, disinhibiting Wts. Ft may sequester Dlish or App from Dachs; loss of Ft increases tethering of Dachs, inhibiting Wts.

Intriguing new evidence suggests that Dachs inhibits Wts by altering its conformation, an effect that involves a Wts-binding Mobs family protein called Mats [6]. An in vivo FRET based sensor of Wts conformation showed that Wts is in a closed, apparently less active conformation in ft, ds and mats mutants, and in an open conformation in dachs mutants. Genetically the dachs effect is downstream of ft and ds and upstream of mats. Thus, in the simplest model, Mats binds and opens Wts, and this is disrupted when Dachs binds Wts. The conformation change is not, however, affected by the Wts phosphorylation mediated by the upstream kinase Hpo, and thus this effect of Ft/Ds branch on the Hippo pathway may be independent of Hpo itself.

If Dachs is so critical, how then is it regulated by Ft? New evidence indicates that there are several ways in which the Ft ICD reduces the levels of subapical Dachs (Figure 2). One involves the F-box E3 ubiquitin ligase Fbxl7 [7,8]. Fbxl7 is recruited to subapical cell junctions by binding to Fat’s ICD. Loss of either Fbxl7, or the Fbxl7-binding region in Fat’s ICD, increases the levels of subapical Dachs and causes moderate overgrowth. There is disagreement about whether Fbxl7 stimulates the ubiquitination of Dachs, and Fbxl7 is not known to bind Dachs itself. Nonetheless, the results strongly suggest that Ft’s ICD organizes a complex for the Fbxl7-mediated ubiquitination of Dachs or another Dachs regulator, thereby reducing Dachs levels or altering Dachs trafficking (Figure 2b).

Recently, two other proteins were shown to bind both Dachs and the Dachs-regulating portions of Fat’s ICD, but instead of reducing Dachs, these act in opposition to Ft and Fbxl7 by increasing subapical Dachs. The proteins are the zDHHC9-like transmembrane palmitoyltransferase Approximated (App) [9], and the newly discovered SH3-containing adaptor protein Dachs ligand with SH3s (Dlish, also called Vamana), which directly binds the Dachs C-terminus [10,11]. app and dlish mutations have similar effects: subapical Dachs accumulation is reduced and cytoplasmic Dachs increased, even in ft mutants (Figure 2a), and app and dlish mutants block ft mutant overgrowth. In vitro evidence suggests that App works in part by palmitoylating Dlish, thereby tethering Dlish-bound Dachs near the cell membrane [10]; subapically-localized App may also bind and tether Dachs and Dlish to membranes, independent of its palmitoyltransferase activity [9]. Intriguingly, App-driven Dlish palmitoylation is reduced by the Ft ICD in vitro, providing a possible regulatory mechanism in vivo: binding to the Ft ICD may sequester App or Dlish from Dachs, thereby reducing the subapical accumulation of Dachs and its access to subapical Wts (Figure 2c).

We note, however, that these models already oversimplify the complex interactions between these mediators, and much remains to be learned. Fbxl7 affects the subapical accumulation of not only Dachs, but also Ft and Ds, through mechanisms that are as yet unknown. App can also palmitoylate and thereby reduce the activity of the Fat ICD, adding an additional way to promote growth [9]. Additional players also need to be incorporated. Loss of a fourth Fat-binding protein, the casein kinase Iε Discs overgrown (Dco), also increases subapical Dachs and causes overgrowth. The Ft ICD is phosphorylated by Dco, and more so when Ft binds to Ds [12,13], but so far the effects of reducing that phosphorylation appear weaker than loss of Dco [14], suggesting that Dco has additional targets. ft and dachs mutations also decrease and increase, respectively, levels of the FERM scaffolding protein Expanded [see [15] and references therein]; Expanded reduces growth by binding and regulating several Hippo pathway members, including by tethering Yki outside the nucleus [16,17]. Dachs-independent functions of Ft, such as its effects in mitochondria (see below), may also affect Hippo pathway activity.

Ds and Hippo signaling

Loss of ds also induces overgrowth and reduces Hippo pathway activity. However, this overgrowth is much weaker than that caused by loss of ft. In part this is because Ft retains substantial growth-suppressing activity when not bound to Ds; Ft activity is not strictly ligand-dependent. But in addition, while the Ds ECD reduces growth by binding Ft and increasing its activity, the Ds ICD can promote growth [18] loss of ds can have two opposite effects. One likely mechanism for the growth-inducing activity of the Ds ICD is again through Dachs: the Ds ICD can attract Dachs to the subapical cell membrane, even in the absence of Ft, and can complex with Dachs (and Dlish) in vitro [10,19-23]. Ds-bound Dachs could in turn bind and inhibit Wts (Figure 1). In fact, interactions between the Ds ICD and myosins may be a general function, as during the control of gut looping in Drosophila the Ds ICD has been shown to bind to and act via Myo31DF, the Drosophila homolog of vertebrate Myo1D [24]. The Ds ICD also stimulates growth through a second pathway, recruiting the Riquiqui WD40 repeat protein and the Minibrain DRYK kinase to the membrane, where they phosphorylate and inhibit Wts [25].

Fat, Ds and PCP

Ft and Ds also regulate a form of tissue patterning known as planar cell polarity, or PCP. PCP can be seen most easily in the coordinate organization of hairs on the wing and abdomen, and in the organization of photoreceptor clusters in the eye. These types of PCP are also regulated by a “core” pathway of PCP proteins (Fz, Dsh, Vang, Pk, Fmi), and Ft and Ds can repolarize the core system. However, there are also types of PCP, such as polarized cell tensions, oriented cell divisions, and hair polarity in the larval denticle belts, that require Fat-Ds signaling but are largely independent of the core PCP pathway (reviewed in [26])

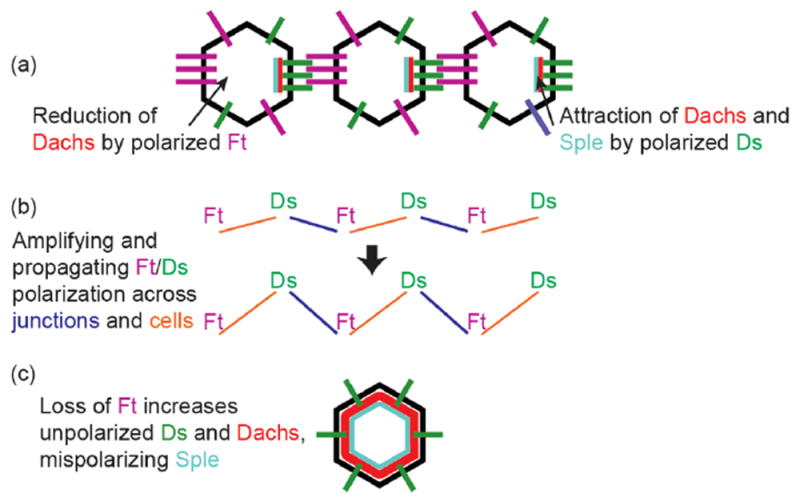

One striking aspect of both pathways is that the core and Ft/Ds proteins become asymmetrically localized in cells, generating cellular asymmetries that are responsible PCP; the steepness of Ft and Ds polarization has even been invoked as a way of regulating cell proliferation via the Hippo pathway. In the case of Ft and Ds, this cell-by-cell protein polarization is established by complementary expression gradients of Ds and the Golgi-resident kinase Four-jointed (Fj); Fj-mediated phosphorylation of the Ft and Ds cadherin repeats promotes Fat binding to Ds, and inhibits Ds binding to Fat. Differences in Ds and Fj expression in neighboring cells, and thereby their binding properties, leads to the preferential concentration of Ds-bound Fat on one cell face, and Fat-bound Ds on the opposite cell face (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Dt and Fs in PCP. (a) Cell-by-cell polarization of Ds and Ft binding leads to reduction of Dachs in the side of the cell with higher Ft, and attraction of Dachs and Sple to the side of the cell with higher Ds. (b) Slight initial differences in the polarity of Ds-Ft binding is amplified, both across cell junctions and by across single cells. (c) Loss of Ft mispolarizes Ds and increases the levels of unpolarized Dachs, leading to the mispolarization of Sple and thus disruption of information conveyed by the core PCP pathway.

Translating what must be very slight initial differences in the expression of Ds and Fj in neighboring cells into robust vectors of Ds-Fat polarization almost certainly requires one or more forms of amplification (Figure 3b). Currently, the amplification mechanisms are poorly understood, but a recent in vitro study using the mammalian homologs Dchs1 and Fat4 suggests that some amplification occurs locally at the individual junctions between cells [27]: there is an intrinsic tendency to favor directional polarization of DCHS1-FAT4 binding at junctions between cultured cells, even between cells expressing similar levels of both proteins. The authors suggest that initially weakly polarized binding at a junction favors further binding of the same polarity, but inhibits binding of the opposite polarity.

The effects of altering Ft-Ds or core protein polarization in one cell is not, however, limited to single junctions, or even a cell’s immediate neighbor; protein polarization, and downstream effects on the tissue’s PCP, can be propagated over several cells. Most models of both Ft-Ds and core PCP suggest that the polarized extracellular binding at one cell face signals within that cell to alter polarization at its opposite face (although there are exceptions; see [28]). This polarized binding then acts in the next cell to affect polarized binding at of its opposite face, which then affects the next cell and the next (Figure 3b). But while the junctional polarization mediated by Ft and Ds is required in most tissues to propagate PCP information from cell to cell, this model has been challenged by the finding that, in the eye, there is significant transmission of PCP signals far into clones that entirely lack Ft or Ds [29]. That is, the polarized Ft/Ds binding at clone boundaries must produce a secondary signal that is independent of Ft and Ds and conveys signaling over up to 40 cells. It is not clear what this secondary signal is. Nonetheless, the shape of the clone affects the strength of the PCP effect in a way that suggests that the secondary signal depends on the strength of boundary Ft-Ds polarization. Further genetic analysis suggests that cis-interactions between the ICDs of Fat and of Ds also impacts PCP signaling.

No matter how it is established, the polarization of Ft and Ds must be transduced into polarized structures or patterns of differentiation. Most of what is known about that transduction again relies on the myosin Dachs. Subapical Dachs is reduced on the cell face with less Ft, and higher on the cell face with more Ds (Figure 3a); this fits with the mechanisms described above, as Ft inhibits Dachs accumulation, and the Ds ICD can attract Dachs. It is currently thought that many of the strong PCP defects observed in ft and ds mutants are due not just to the loss of Ft/Ds polarity information, but to the accumulation of abnormally high levels of Dachs, which then disrupts PCP signaling carried by other pathways (Figure 3c). Heightened Dachs affects PCP indirectly by decreasing Wts activity [15,30] and also misdirects the core PCP pathway by binding, along with Ds, to the Sple isoform of Pk [21,23,31,32]. Indeed, PCP in ft and ds mutants is improved by simultaneous loss of dachs or sple [3,23,33].

Recent studies have also unveiled a critical role of Fat, Ds and Dachs in the polarization of cell-cell adhesions and adherens junction tension. Using clonal analysis, mathematical modeling and laser ablation of junctions, researchers showed that ft clones have increased tension at the border of clones, where it abuts wildtype tissue, but reduced junctional tension inside the ft clones [19]. Dachs is needed for these effects on junctional tension, both directly by concentrating at clone boundaries, and indirectly by reducing internal tension through the Hippo pathway [20]. A role for Fat in regulation of junctions was also shown in the embryo [34], and in larval tissues [35,36], with a context-dependent role for Dachs in junctional tension. Dachs is required for the effects on Fat and Ds on the polarity of cell divisions in imaginal discs [37].

Nonetheless, there are clearly forms of Fat/Ds PCP that are independent of Dachs: some PCP defects remain in ft dachs double mutants, including the eye, there are no PCP defects in dachs null eye clones, a fragment of Ft’s ICD that does not affect Dachs levels or Hippo activity can improve ft mutant PCP in the wing and abdomen, and PCP changes can be propagated from a source of ectopic Ds ECD through eyes or larval epidermis lacking Dachs [3,10,18,29,30,33]. The latter is important, as it shows that Dachs-independent information can be instructional. Several pathways might be involved. Ft/Ds cadherins affect, and may direct, the polarity of the microtubule cytoskeleton [31,34,38,39], which might affect PCP by directing delivery of core PCP components to the correct membrane domain. Another candidate for conveying the PCP signal is the transcriptional co-repressor Atrophin, which genetically and physically interacts with Ft [40]. However Atrophin only affects PCP in equatorial regions in the eye [29], and while it regulates many pathways involved in cell and organ patterning [41], the transcriptional targets that specifically regulate PCP downstream of Atrophin are not yet clear

Mitochondrial Fat

Another aspect of cell biology that Ft regulates is metabolism, which impacts growth, the Hippo pathway, and PCP in the eye. Surprisingly, the cytoplasmic domain of Ft contains multiple mitochondrial targeting signals, and the cytoplasmic domain is cleaved, releasing a fragment that is imported into mitochondria, where it binds to and stabilizes Complex I. ft mutants have reduced levels of Complex I, a switch to glycolysis, and developmental delays [42]. Interestingly, disruption of core components of Complex I also yields PCP phenotypes in the eye, suggesting that signaling from the mitochondria may also act to direct PCP.

FAT4, DCHS1 and signaling in vertebrates

There has been a great deal of debate in recent years about whether the signaling functions of Drosophila Ft and Ds have been retained, altered or lost in their vertebrate homologs, FAT4 and DCHS1. Mutations in FAT4 and /or DCHS1 lead to human diseases, such as Van Maldergem [43] and Hennekam syndromes [44], and are found in a wide variety of cancers [45-48]. In mammals FAT4 and DCHS1 bind and form a cassette that affects several proliferative (frequently loss of FAT4 surprisingly leads to less proliferation overall) and polarity processes, such as the number of neuronal, nephrogenic and chondrocyte progenitors, their polarity, and neural migrations [49-52]. The similarities to Drosophila extend to gene expression: in both flies and mammals Fat cadherins repress expression of fj or its homolog fjx1, as part of a negative feedback loop [53,54].

But although there are regions of very high homology between the ICDs of Ft and human FAT4, loss of most of these, except the Fbxl7-binding domain of Ft, have little effect on Ft’s Hippo and PCP activities in flies; conversely, the FAT4 ICD has little Hippo activity in flies [14,18,55,56]. Even more surprisingly, the type XX myosin Dachs and its binding partner Dlish, although present in many taxa including Cephalochordates, are absent in vertebrates. While it is possible their function has been coopted by other, perhaps similar proteins, at this point the Dachs-dependent pathways, which are so crucial in flies, appear to be absent. In fact, some of the growth effects of FAT4 and DCHS1 may not involve the Hippo pathway: loss of Yki homologs YAP or TAZ does not affect the increased number of nephrogenic progenitors [50,57] or chondrocytes [58], seen in FAT4 and DCHS1 mutants, nor does phosphorylation of the Hippo pathway kinase appear altered in the mutant tissues.

Nonetheless, other proliferative effects of FAT4 and DCHS1 have been linked to changes in Hippo pathway activity or YAP and TAZ [43,47,59], and two recent studies indicate that this may occur via a novel pathway: FAT4 regulates post-embryonic proliferation independently of the Hpo (MST) and Wts (LATS) kinases by sequestering YAP at the cell surface, thereby reducing YAP-driven transcription; this link from FAT4 to YAP is provided by AMOT (Angiomotin) [55,60]. This mechanism cannot be used in Drosophila because it lacks an AMOT homolog, and the AMOT homologs in other insects may lack critical domains. The mechanism is, however, similar to one used by Drosophila Expanded, which binds Yki and may sequester it at junctions [16,17]. As the vertebrate homolog of Expanded has lost its Yki/YAP binding domains, it is possible that AMOT has taken its place.

FAT4 and DCHS1 are also required for normal PCP or directed cell migration in a variety of tissues, including the forming skeleton, the kidney and the central nervous system [43,52,53,58,61], and in some cases the patterns and gradients of expression are likely to be instructional. The downstream pathways are less well understood, but some may be evolutionarily conserved, as the FAT4 ICD can improve PCP in ft mutant flies [14]. It also remains to be seen whether cell-by-cell polarization of Ds-Fat binding found in Drosophila has been conserved during evolution; so far, FAT4 polarization has only been detected in vitro. Nonetheless, it should be noted that polarization of endogenous Ds and Fat in Drosophila also went undetected for many years; it was initially inferred from the polarization of Dachs, and direct confirmation required examining the boundaries between cells with tagged and untagged proteins.

The mitochondrial function of Drosophila Ft has not been detected in its vertebrate homolog FAT4, but a mitochondrial function has been reported that utilizes a mitochondrial fragment of the Fat-like family member FAT1 [62]. Intriguingly, FAT1 has also been reported bind to mammalian Atrophins [63], instead of FAT4, providing another example of how functions may have been interchanged between different Fat cadherins during evolution. The finding that FAT1 and FAT4 form cis-dimers [51] may help explain how swapping of function might have been achieved with minimal disruption during evolution. Strong genetic interactions exist between other Fat cadherins during mouse development [61], but the physical basis underlying those interactions is still unknown.

Remaining questions

While remarkable progress has been made in the past 5 years in understanding how Ft and Ds regulate Hippo pathway activity, many questions still remain unanswered. How Ft regulates signaling with Ds (and even more how Ds reverse signaling occurs) is far from complete, as is our understanding of how Ft cadherins regulate PCP. Why is the extracellular domain so large for Ft and Ds, and why is the size so conserved through evolution? Some studies have suggested that FAT4/DCHS1 extend fully when interacting [27], but others suggest a mechanism by which these large cadherins fold up [64] with very different implication for how far apart interacting cells are spaced. What are the functions of the laminG and EGF domains? How does Fat regulate mechanical properties of cells and tissues? These and many other questions are likely to be addressed soon as more attention turns to these fascinating, challenging and multifaceted cell adhesion molecules.

Acknowledgments

SB is supported by funding from NIH (R01 GM124377). HM is supported by a CIHR Foundation Grant, FDN 143319, a Canada Research Chair, NSERC funding and start-up funding from Washington University School of Medicine.

Suggested starred papers of special interest in past two years

*Zhang et al 2016*

*Misra & Irvine 2016*

These two papers identify a novel component of the Ft pathway, an SH3 domain protein known as either Dlish (Zhang et al., 2016) or Vamana (Misra & Irvine, 2016) that binds Dachs and the Ft ICD, linking Ds-Ft signaling to the localization and levels of the Wts-inhibiting myosin Dachs, and thereby the regulation of Yki activity. (Zhang et al., 2016) provide evidence that Dlish/Vamana is regulated by the zDHHC9-like palmitoyltransferase Approximated.

*Matakatsu et al, 2017.

The authors show that the zDHHC9-like transmembrane palmitoyltransferase Approximated can palmitoylate the ICD of Ft, thereby repressing Ft’s ability to repress tissue growth. This counteracts the action of Dco to phosphorylate Ft and activate Ft. Approximated also has palmitoyltransferase-independent activity and binds Dachs.

*Rodrigues-Campos & Thompson 2014

*Bosch et al. 2014

These two papers identify the F-box E3 ubiquitin ligase Fbxl7 as a key component of the Ds-Ft pathway. Fbxl7 controls tissue growth by binding the Ft ICD and regulating the subapical accumulation of Dachs and other pathway components.

*Vrabioiu & Struhl 2015

The authors use an in vivo FRET based sensor of Wts conformation to show that Wts is in a closed, apparently less active conformation in ft, ds and mats mutants, and in an open conformation in dachs mutants. This suggests a model in which Wts conformation and activity is regulated by ft via dachs.

*Sing et al. 2014

This paper shows that the cytoplasmic domain of Ft contains mitochondrial targeting sequences, that Ft binds directly to mitochondrial Complex I components, and that loss of ft leads to defective mitochondria and increased glycolysis. Interestingly, defects in mitochondrial Complex I components themselves were found to cause PCP defects, suggesting a novel signal from mitochondria can impact PCP.

*Bosveld et al 2016

The authors use laser ablation of cell junctions to measure cell tensions after changing components of the Ds-Ft pathway. They show that loss of ft in clones leads to increased junctional tension at clone boundaries due to the Ds-driven accumulation of Dachs, but decreased tension inside clones due to reduced Hippo pathway activity.

*Ragni et al, 2017

This paper identifies a mechanism in mammals for the regulation of YAP/TAZ activity by FAT4: Fat4 binds the adaptor protein AMOT at the cell surface, and that AMOT in turn binds to YAP and sequesters it from the nucleus, reducing nuclear YAP activity.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hulpiau P, van Roy F. Molecular evolution of the cadherin superfamily. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:349–369. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enderle L, McNeill H. Hippo gains weight: added insights and complexity to pathway control. Sci Signal. 2013;6:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao Y, Rauskolb C, Cho E, Hu WL, Hayter H, Minihan G, Katz FN, Irvine KD. Dachs: an unconventional myosin that functions downstream of Fat to regulate growth, affinity and gene expression in Drosophila. Development. 2006;133:2539–2551. doi: 10.1242/dev.02427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho E, Feng Y, Rauskolb C, Maitra S, Fehon R, Irvine KD. Delineation of a Fat tumor suppressor pathway. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1142–1150. doi: 10.1038/ng1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauskolb C, Pan G, Reddy BV, Oh H, Irvine KD. Zyxin links fat signaling to the hippo pathway. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vrabioiu AM, Struhl G. Fat/Dachsous Signaling Promotes Drosophila Wing Growth by Regulating the Conformational State of the NDR Kinase Warts. Dev Cell. 2015;35:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodrigues-Campos M, Thompson BJ. The ubiquitin ligase FbxL7 regulates the Dachsous-Fat-Dachs system in Drosophila. Development. 2014;141:4098–4103. doi: 10.1242/dev.113498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch JA, Sumabat TM, Hafezi Y, Pellock BJ, Gandhi KD, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila F-box protein Fbxl7 binds to the protocadherin fat and regulates Dachs localization and Hippo signaling. Elife. 2014;3:e03383. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matakatsu H, Blair SS, Fehon RG. The palmitoyltransferase Approximated promotes growth via the Hippo pathway by palmitoylation of Fat. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:265–277. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201609094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Wang X, Matakatsu H, Fehon R, Blair SS. The novel SH3 domain protein Dlish/CG10933 mediates fat signaling in Drosophila by binding and regulating Dachs. Elife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.16624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misra JR, Irvine KD. Vamana Couples Fat Signaling to the Hippo Pathway. Dev Cell. 2016;39:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sopko R, Silva E, Clayton L, Gardano L, Barrios-Rodiles M, Wrana J, Varelas X, Arbouzova NI, Shaw S, Saburi S, et al. Phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor fat is regulated by its ligand Dachsous and the kinase discs overgrown. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1112–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng Y, Irvine KD. Processing and phosphorylation of the Fat receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11989–11994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811540106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan G, Feng Y, Ambegaonkar AA, Sun G, Huff M, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Signal transduction by the Fat cytoplasmic domain. Development. 2013;140:831–842. doi: 10.1242/dev.088534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng Y, Irvine KD. Fat and Expanded act in parallel to regulate growth through Warts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20362–20367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706722105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badouel C, Gardano L, Amin N, Garg A, Rosenfeld R, Le Bihan T, McNeill H. The FERM-domain protein Expanded regulates Hippo pathway activity via direct interactions with the transcriptional activator Yorkie. Dev Cell. 2009;16:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh H, Reddy BV, Irvine KD. Phosphorylation-independent repression of Yorkie in Fat-Hippo signaling. Dev Biol. 2009;335:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Separating planar cell polarity and Hippo pathway activities of the protocadherins Fat and Dachsous. Development. 2012;139:1498–1508. doi: 10.1242/dev.070367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bosveld F, Guirao B, Wang Z, Riviere M, Bonnet I, Graner F, Bellaiche Y. Modulation of junction tension by tumor suppressors and proto-oncogenes regulates cell-cell contacts. Development. 2016;143:623–634. doi: 10.1242/dev.127993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosveld F, Bonnet I, Guirao B, Tlili S, Wang Z, Petitalot A, Marchand R, Bardet PL, Marcq P, Graner F, et al. Mechanical control of morphogenesis by Fat/Dachsous/Four-jointed planar cell polarity pathway. Science. 2012;336:724–727. doi: 10.1126/science.1221071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayukawa T, Akiyama M, Mummery-Widmer JL, Stoeger T, Sasaki J, Knoblich JA, Senoo H, Sasaki T, Yamazaki M. Dachsous-dependent asymmetric localization of spiny-legs determines planar cell polarity orientation in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2014;8:610–621. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ambegaonkar AA, Pan G, Mani M, Feng Y, Irvine KD. Propagation of Dachsous-Fat planar cell polarity. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1302–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ambegaonkar AA, Irvine KD. Coordination of planar cell polarity pathways through Spiny-legs. Elife. 2015:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez-Morales N, Geminard C, Lebreton G, Cerezo D, Coutelis JB, Noselli S. The Atypical Cadherin Dachsous Controls Left-Right Asymmetry in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2015;33:675–689. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degoutin JL, Milton CC, Yu E, Tipping M, Bosveld F, Yang L, Bellaiche Y, Veraksa A, Harvey KF. Riquiqui and minibrain are regulators of the hippo pathway downstream of Dachsous. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1176–1185. doi: 10.1038/ncb2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matis M, Axelrod JD. Regulation of PCP by the Fat signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2207–2220. doi: 10.1101/gad.228098.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loza O, Heemskerk I, Gordon-Bar N, Amir-Zilberstein L, Jung Y, Sprinzak D. A synthetic planar cell polarity system reveals localized feedback on Fat4-Ds1 complexes. Elife. 2017:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rovira M, Saavedra P, Casal J, Lawrence PA. Regions within a single epidermal cell of Drosophila can be planar polarised independently. Elife. 2015:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma P, McNeill H. Regulation of long-range planar cell polarity by Fat-Dachsous signaling. Development. 2013;140:3869–3881. doi: 10.1242/dev.094730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brittle A, Thomas C, Strutt D. Planar Polarity Specification through Asymmetric Subcellular Localization of Fat and Dachsous. Curr Biol. 2012;22:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olofsson J, Sharp KA, Matis M, Cho B, Axelrod JD. Prickle/spiny-legs isoforms control the polarity of the apical microtubule network in planar cell polarity. Development. 2014;141:2866–2874. doi: 10.1242/dev.105932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merkel M, Sagner A, Gruber FS, Etournay R, Blasse C, Myers E, Eaton S, Julicher F. The balance of prickle/spiny-legs isoforms controls the amount of coupling between core and fat PCP systems. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2111–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saavedra P, Brittle A, Palacios IM, Strutt D, Casal J, Lawrence PA. Planar cell polarity: the Dachsous/Fat system contributes differently to the embryonic and larval stages of Drosophila. Biol Open. 2016;5:397–408. doi: 10.1242/bio.017152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcinkevicius E, Zallen JA. Regulation of cytoskeletal organization and junctional remodeling by the atypical cadherin Fat. Development. 2013;140:433–443. doi: 10.1242/dev.083949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawlor KT, Ly DC, DiNardo S. Drosophila Dachsous and Fat polarize actin-based protrusions over a restricted domain of the embryonic denticle field. Dev Biol. 2013;383:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donoughe S, DiNardo S. dachsous and frizzled contribute separately to planar polarity in the Drosophila ventral epidermis. Development. 2011;138:2751–2759. doi: 10.1242/dev.063024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mao Y, Tournier AL, Bates PA, Gale JE, Tapon N, Thompson BJ. Planar polarization of the atypical myosin Dachs orients cell divisions in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2011;25:131–136. doi: 10.1101/gad.610511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matis M, Russler-Germain DA, Hu Q, Tomlin CJ, Axelrod JD. Microtubules provide directional information for core PCP function. Elife. 2014;3:e02893. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harumoto T, Ito M, Shimada Y, Kobayashi TJ, Ueda HR, Lu B, Uemura T. Atypical cadherins Dachsous and Fat control dynamics of noncentrosomal microtubules in planar cell polarity. Dev Cell. 2010;19:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fanto M, Clayton L, Meredith J, Hardiman K, Charroux B, Kerridge S, McNeill H. The tumor-suppressor and cell adhesion molecule Fat controls planar polarity via physical interactions with Atrophin, a transcriptional co-repressor. Development. 2003;130:763–774. doi: 10.1242/dev.00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeung K, Boija A, Karlsson E, Holmqvist PH, Tsatskis Y, Nisoli I, Yap D, Lorzadeh A, Moksa M, Hirst M, et al. Atrophin controls developmental signaling pathways via interactions with Trithorax-like. Elife. 2017:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sing A, Tsatskis Y, Fabian L, Hester I, Rosenfeld R, Serricchio M, Yau N, Bietenhader M, Shanbhag R, Jurisicova A, et al. The atypical cadherin fat directly regulates mitochondrial function and metabolic state. Cell. 2014;158:1293–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cappello S, Gray MJ, Badouel C, Lange S, Einsiedler M, Srour M, Chitayat D, Hamdan FF, Jenkins ZA, Morgan T, et al. Mutations in genes encoding the cadherin receptor-ligand pair DCHS1 and FAT4 disrupt cerebral cortical development. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1300–1308. doi: 10.1038/ng.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alders M, Al-Gazali L, Cordeiro I, Dallapiccola B, Garavelli L, Tuysuz B, Salehi F, Haagmans MA, Mook OR, Majoie CB, et al. Hennekam syndrome can be caused by FAT4 mutations and be allelic to Van Maldergem syndrome. Hum Genet. 2014;133:1161–1167. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1456-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida S, Yamashita S, Niwa T, Mori A, Ito S, Ichinose M. Ushijima T: Epigenetic inactivation of FAT4 contributes to gastric field cancerization. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:136–145. doi: 10.1007/s10120-016-0593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilehchian Langroudi M, Nikbakhsh N, Samadani AA, Fattahi S, Taheri H, Shafaei S, Amirbozorgi G, Pilehchian Langroudi R, Akhavan-Niaki H. FAT4 hypermethylation and grade dependent downregulation in gastric adenocarcinoma. J Cell Commun Signal. 2017;11:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s12079-016-0355-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma L, Cui J, Xi H, Bian S, Wei B, Chen L. Fat4 suppression induces Yap translocation accounting for the promoted proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2016;17:36–47. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1108488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hou L, Chen M, Zhao X, Li J, Deng S, Hu J, Yang H, Jiang J. FAT4 functions as a tumor suppressor in triple-negative breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mao Y, Kuta A, Crespo-Enriquez I, Whiting D, Martin T, Mulvaney J, Irvine KD, Francis-West P. Dchs1-Fat4 regulation of polarized cell behaviours during skeletal morphogenesis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11469. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bagherie-Lachidan M, Reginensi A, Pan Q, Zaveri HP, Scott DA, Blencowe BJ, Helmbacher F, McNeill H. Stromal Fat4 acts non-autonomously with Dchs1/2 to restrict the nephron progenitor pool. Development. 2015;142:2564–2573. doi: 10.1242/dev.122648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Badouel C, Zander MA, Liscio N, Bagherie-Lachidan M, Sopko R, Coyaud E, Raught B, Miller FD, McNeill H. Fat1 interacts with Fat4 to regulate neural tube closure, neural progenitor proliferation and apical constriction during mouse brain development. Development. 2015;142:2781–2791. doi: 10.1242/dev.123539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zakaria S, Mao Y, Kuta A, de Sousa CF, Gaufo GO, McNeill H, Hindges R, Guthrie S, Irvine KD, Francis-West PH. Regulation of neuronal migration by Dchs1-Fat4 planar cell polarity. Curr Biol. 2014;24:1620–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M, Quaggin SE, Harrison R, Mount R, McNeill H. Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1010–1015. doi: 10.1038/ng.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simon MA. Planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye is directed by graded Four-jointed and Dachsous expression. Development. 2004;131:6175–6184. doi: 10.1242/dev.01550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bossuyt W, Chen CL, Chen Q, Sudol M, McNeill H, Pan D, Kopp A, Halder G. An evolutionary shift in the regulation of the Hippo pathway between mice and flies. Oncogene. 2014;33:1218–1228. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao X, Yang CH, Simon MA. The Drosophila Cadherin Fat regulates tissue size and planar cell polarity through different domains. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mao Y, Francis-West P, Irvine KD. Fat4/Dchs1 signaling between stromal and cap mesenchyme cells influences nephrogenesis and ureteric bud branching. Development. 2015;142:2574–2585. doi: 10.1242/dev.122630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuta A, Mao Y, Martin T, Ferreira de Sousa C, Whiting D, Zakaria S, Crespo-Enriquez I, Evans P, Balczerski B, Mankoo B, et al. Fat4-Dchs1 signalling controls cell proliferation in developing vertebrae. Development. 2016;143:2367–2375. doi: 10.1242/dev.131037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Das A, Tanigawa S, Karner CM, Xin M, Lum L, Chen C, Olson EN, Perantoni AO, Carroll TJ. Stromal-epithelial crosstalk regulates kidney progenitor cell differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ncb2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ragni CV, Diguet N, Le Garrec JF, Novotova M, Resende TP, Pop S, Charon N, Guillemot L, Kitasato L, Badouel C, et al. Amotl1 mediates sequestration of the Hippo effector Yap1 downstream of Fat4 to restrict heart growth. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14582. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saburi S, Hester I, Goodrich L, McNeill H. Functional interactions between Fat family cadherins in tissue morphogenesis and planar polarity. Development. 2012;139:1806–1820. doi: 10.1242/dev.077461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cao LL, Riascos-Bernal DF, Chinnasamy P, Dunaway CM, Hou R, Pujato MA, O’Rourke BP, Miskolci V, Guo L, Hodgson L, et al. Control of mitochondrial function and cell growth by the atypical cadherin Fat1. Nature. 2016;539:575–578. doi: 10.1038/nature20170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hou R, Sibinga NE. Atrophin proteins interact with the Fat1 cadherin and regulate migration and orientation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6955–6965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809333200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsukasaki Y, Miyazaki N, Matsumoto A, Nagae S, Yonemura S, Tanoue T, Iwasaki K, Takeichi M. Giant cadherins Fat and Dachsous self-bend to organize properly spaced intercellular junctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16011–16016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418990111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]