Abstract

Tissue softening accompanies the ripening of many fruit and initiates the processes of irreversible deterioration. Expansins are plant cell wall proteins proposed to disrupt hydrogen bonds within the cell wall polymer matrix. Expression of specific expansin genes has been observed in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) meristems, expanding tissues, and ripening fruit. It has been proposed that a tomato ripening-regulated expansin might contribute to cell wall polymer disassembly and fruit softening by increasing the accessibility of specific cell wall polymers to hydrolase action. To assess whether ripening-regulated expansins are present in all ripening fruit, we examined expansin gene expression in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.). Strawberry differs significantly from tomato in that the fruit is derived from receptacle rather than ovary tissue and strawberry is non-climacteric. A full-length cDNA encoding a ripening-regulated expansin, FaExp2, was isolated from strawberry fruit. The deduced amino acid sequence of FaExp2 is most closely related to an expansin expressed in early tomato development and to expansins expressed in apricot fruit rather than the previously identified tomato ripening-regulated expansin, LeExp1. Nearly all previously identified ripening-regulated genes in strawberry are negatively regulated by auxin. Surprisingly, FaExp2 expression was largely unaffected by auxin. Overall, our results suggest that expansins are a common component of ripening and that non-climacteric signals other than auxin may coordinate the onset of ripening in strawberry.

Fruit ripening is a developmental process that is regulated by multiple factors, including age, environmental signals, and endogenous hormones. Auxin originating in the achenes regulates strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.) fruit development and maturation. Auxin is required for growth and early fruit development but acts to delay ripening (Given et al., 1988). Ripening of strawberry fruit is non-climacteric, occurring in the absence of ethylene. A number of ripening-associated genes are expressed in strawberry fruit and encode proteins potentially involved in respiratory, metabolic, and physical changes in the ripening fruit tissue, including cell wall metabolism. Specifically, genes encoding pectate lyase and cellulase are activated at the onset of ripening and their expression is reduced by the application of exogenous auxin (Medina-Escobar et al., 1997; Brummell et al., 1999). Indeed, in strawberry, expression of nearly all of the ripening-associated genes studied to date is suppressed by auxin (Manning, 1994, 1998). This result suggests that as strawberry fruit mature, the declining levels of endogenous auxin activate the expression of a number of ripening-associated genes, which in turn initiate the process of fruit ripening (Manning, 1994, 1998). Only a few genes expressed late in ripening strawberries have been shown to be unaffected by auxin (Manning, 1998).

Expansins are plant cell wall proteins with no detectable hydrolase or xyloglucan endotransglycosylase enzymatic activity, but which induce increased extensibility in isolated plant cell walls in vitro (McQueen-Mason et al., 1992, 1993, 1995). Expansins have been proposed to disrupt hydrogen bonds between cellulose and hemicellulose microfibrils in the cell wall, thereby allowing movement and rearrangement of these cell wall polymers during expansive growth (McQueen-Mason and Cosgrove, 1994). Consistent with this proposal, expansins are expressed in growing organs such as apical meristems, expanding green fruit, and elongating hypocotyls (Cosgrove, 1997; Fleming et al., 1997). However, we have demonstrated previously that an expansin, LeExp1, is expressed in ripening tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) fruit, a tissue that is not undergoing expansive growth but one that is characterized by extensive disassembly of cell wall polymers (Rose et al., 1997). We proposed that this ripening-regulated expansin might contribute to cell wall polymer disassembly and fruit softening by increasing access of specific cell wall polymers to hydrolase action (Rose and Bennett, 1999). Because of the potential significance of ripening-associated expansins in tomato fruit softening, we investigated the potential that similar processes were also active in non-climacteric fruit such as strawberry. The results indicate that the expression of an expansin gene, FaExp2, is ripening regulated in strawberry fruit. FaExp2 mRNA is detectable at the onset of ripening and becomes abundant in mid-ripe fruit. However, FaExp2 is not closely related to LeExp1, and, unlike most other strawberry ripening-regulated genes, the expression of FaExp2 is not controlled exclusively by auxin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Strawberry fruit (Fragaria × ananassa Duch. cv Chandler) were harvested and classified according to their ripening stage as: small green, large green, white, turning, ripe, and overripe. The peduncle and calyx were removed, and the fruit were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Vegetative tissues were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use.

Treatments

Auxin Treatment

The auxin treatment was performed over half of the fruit surface, maintaining the other half as a control. Six fruits at the white or turning stage were used in each experiment and, when necessary, the achenes were removed with sharp tweezers. A lanolin paste containing 1 mm naphthylacetic acid (NAA) and 1% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide was smeared over the treated half of the fruit, while a similar paste without NAA was applied to the control half. To avoid dehydration, the peduncle of each fruit was immersed in a microcentrifuge tube containing distilled water. Fruit were maintained for 3 d at 20°C in a 5-L chamber with a continuous flow (20 L/h) of humidified air. At the conclusion of the treatment the calyx and peduncle were removed, and the treated and control halves were cut apart, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80° until use.

Ethylene Treatment

Six fruit at the white stage were treated for 3 d at 20°C in a 5-L chamber with a continuous flow (20 L/h) of humidified air containing 10 μL L−1 of ethylene. Control fruit were maintained in similar conditions in the absence of ethylene. The peduncle of each fruit was submerged in distilled water to avoid dehydration. After treatment, the calyx and peduncle were removed and the fruit were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

Firmness

The firmness of fresh fruit was measured using a texture analyzer (TA.XT2, Stable Micro Systems Texture Technologies, Scarsdale, NY) fitted with a flat probe (5-mm diameter). Each fruit was compressed 0.5 mm at a speed rate of 0.5 mm s−1 and the maximum force of resistance during this test was recorded. Each fruit was measured twice on opposite sides of its equator, and 20 fruit at each ripening stage were assayed. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and the means compared by the lsd test at a significance level of 0.05.

cDNA Library Construction and Screening

A cDNA library was constructed by using 5 μg of poly(A+) RNA from ripe strawberry fruit, and a λZAP cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The cDNAs were cloned into the Uni-ZAP XR vector (Stratagene) and packaged in Gigapack III gold packaging extract (Stratagene). The primary library was immediately amplified according to the manufacturer's protocols. The amplified library had a titer of 1.3 × 1010 pfu mL−1. For screening, 5.2 × 105 pfu were plated and plaque lifts were performed. The filters were prehybridized for 4 h at 42°C in a solution containing 50% (v/v) formamide, 6× SSPE, 5× Denhart's solution, 150 μg mL−1 denatured salmon sperm DNA, 0.01% (w/v) sodium PPi, and 0.5% (w/v) SDS. Then, the solution was replaced by another fresh aliquot, labeled probe 1 (see below) was added, and the filters were hybridized overnight at 42°C. Hybridized filters were washed twice for 20 min at 42°C in 2× SSC, 0.01% (w/v) sodium PPi, and 0.1% (w/v) SDS, and then three times for 30 min at 65°C in 0.2× SSC, 0.01% (w/v) sodium PPi, and 0.1% (w/v) SDS. After washing, filters were prepared for autoradiography and exposed to x-ray film (X-OMAT AR, Kodak, Rochester, NY) with an intensifying screen at −80°C.

Positive plaques were carried through two additional rounds of screening for purification, and phagemid DNA was excised. Positive clones were sequenced at the Plant Genetics Facility at the University of California, Davis, with T3 primers using a sequencer (model 377, Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Both strands of the clone of interest (FaExp2) were completely sequenced using T7 and internal primers. Sequence analyses were carried out using the MacDNAsis Pro 3.5 software package. The isolated cDNA contained complete open reading frames, and the deduced amino acid sequence alignments were done using Clustal V multiple alignment software (Higgins et al., 1992).

Protein Extraction SDS-PAGE Analysis

For total protein extraction, strawberry fruit tissue was ground in liquid N2 and homogenized in sample buffer (0.125 m Tris-HCl, 4% [w/v] SDS, 20% [v/v] glycerol, and 10% [v/v] 2-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.8) (Laemmli, 1970). Equal amounts of total protein were loaded onto a 1-mm-thick 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gel and run for 1.0 h at 120 V. For visualization of total proteins, the gels were stained in Coomassie Blue (0.25% [w/v] in 50% [v/v] methanol and 10% [v/v] acetic acid) and destained in 30% (v/v) methanol and 10% (v/v) acetic acid.

Western Blotting

For western blotting, proteins were transferred from the polyacryamide gels to a polyvinylidene difluoride filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA) using a gel blotter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The transfer was in 0.01 m 3-(cyclohexylamino)propanesulfonic acid (CAPS) and 10% (w/v) methanol at 100 V for 1 h. After transfer, the polyvinylidene difluoride filter was blocked with nonfat milk and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with the primary polyclonal antibodies (anti-LeExp1, J.K.C. Rose and A.B. Bennett, unpublished data). LeExp1 antibodies were used at a 1:2,000 dilution. Cross-reaction with the antibodies was revealed using the alkaline phosphatase reaction of the conjugated secondary anti-rabbit antibody.

Preparation of Probes

Probe 1 was prepared from FaExp1 (Rose et al., 1997) by a random primer labeling method (Feinberg and Vogelstein, 1983), and used for screening the cDNA library. Probe 2 was prepared by PCR amplification of bases 2 to 151 of FaExp2, and the purified product was used as a template in a random primer labeling reaction. This probe was used for northern and Southern hybridization. Probe 3 was prepared by amplifying PCR bases 4 to 322 of FaCel1 (Harpster et al., 1998), and the purified product was used as a template in the random primer labeling method.

RNA Isolation and RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from frozen fruit and vegetative tissues by the hot borate method (Wan and Wilkins, 1994). Each RNA sample (10 μg) was analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.2% (w/v) agarose and 1% (v/v) formaldehyde denaturing gel, and then transferred to Hybond-N membrane (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech UK, Buckinghamshire, UK). The membrane was hybridized with the probe 2 at 42°C and then washed three times for 20 min at 55°C with 0.2× SSC, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, and 0.01% (w/v) sodium PPi. The blot was exposed to x-ray film (X-OMAT AR, Kodak) with an intensifying screen at −80°C, and the film was developed according to the manufacturers' recommendation. Blots were stripped of hybridizing probe and hybridized a second time to probe 3 for FaCel1.

Genomic DNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from young strawberry (cv Chandler) leaves as described in Sambrook et al. (1989). Aliquots of 20 μg were digested with the indicated restriction enzymes, electrophoresed on 0.8% (w/v) agarose gel, and transferred to Hybond-N membrane. The blot was hybridized with probe 2 and washed under the same conditions described above for northern hybridization. The membrane was exposed to a phosphor imaging plate and analyzed with a phosphor imager (model BAS 1000, Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo) and MACBAS software (Fuji Photo Film).

RESULTS

Identification of FaExp2

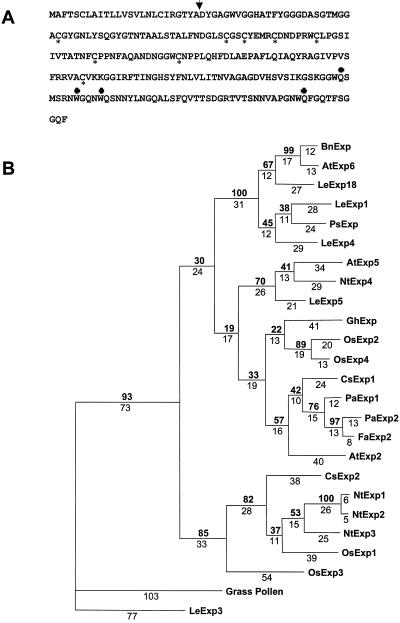

A single positive clone encoding a putative strawberry fruit expansin was identified by hybridization of a partial cDNA clone of a previously identified strawberry fruit expansin (probe 1) to the strawberry ripe fruit cDNA library. Surprisingly, the single positive cDNA clone, FaExp2 (GenBank accession no. AF159563), was divergent from the previously identified FaExp1 cDNA fragment (GenBank accession no. AF163812, Rose et al., 1997). The FaExp2 cDNA clone is 1,180-bp long and contains a 44-bp 5′ untranslated region, an open reading frame of 759, and 377 bp prior to the poly(A+) sequence. The 5′ untranslated region contains a single stop codon 30 bp upstream of the first deduced Met. The FaExp2 deduced amino acid sequence suggests that a signal peptide terminating at the 25th amino acid could be removed in transit to the cell wall compartment (Fig. 1A; von Heijne 1986). The predicted mature 24.2-kD strawberry fruit expansin protein encoded by FaExp2 has a predicted pI of 7.7. Eight Cys residues and four Trp residues, the latter potentially forming a cellulose binding domain, conserved in all expansins sequenced are indicated in Figure 1A (Shcherban et al., 1995; Rose and Bennett, 1999).

Figure 1.

A, Deduced amino acid sequence from FaExp2. The site of cleavage of putative signal sequence is indicated by an arrow. Conserved Cys residues found in all sequenced expansins are marked by an asterisk below, and conserved Trp residues by a cross above the sequence. B, Phylogenetic tree of full-length deduced amino acid sequences of 24 expansins using Lolium perenne pollen allergen (M57474) as an outgroup. Alignments was made using ClustalV multiple sequence software (Higgins et al., 1992) and phylogenetic relationships defined by PAUP software using a heuristic search with 100 replicates. A single tree was obtained (l = 1189, ci = 0.675, ri = 0.587). Bootstrap values are indicated in bold above, and branch lengths are indicated below the branches. Deduced amino acid sequences and GenBank accession numbers are: Arabidopsis, AtExp2 (U30481), Exp5 (U30478), and Exp6 (U30480); Brassica napus, BnExp (AJ000885); Cucumis sativus, CsExp1 (U30382) and CsExp2 (U30460); Fragaria × ananassa, FaExp2 (AF159563); Gossypium hirsutum, GhExp (AF043284); Lycopersicon esculentum, LeExp1 (U82123), LeExp3 (AF059487), LeExp4 (AF059488), LeExp5 (AF059489), and LeExp18 (AJ004997); Nicotiana tabacum, NtExp1 (AF049350), NtExp2 (AF049351), NtExp3 (AF049352), and NtExp4 (AF049353); Oryza sativa, OsExp1 (Y07782), OsExp2 (U30477), OsExp3 (U30479), and OsExp4 (U85246); Prunus armeniaca, PaExp1 (U93167) and PaExp2 (AF038815); and Pisum sativum, PsExp (X85187).

Amino acid sequence comparisons indicate that FaExp2 is most similar (83% and 89% identical, respectively) to expansins expressed in apricot fruit (Pa-Exp1; U93167; Pa-Exp2, AF038815) and are closely related to a large class of expansins that have been identified in elongating cotton fibers (Gh-Exp1, AF043284; Orford and Timmis, 1998), rice (Os-Exp1, Y07782; Os-Exp4, U85246; Cho and Kende, 1997), cucumber (Cs-Exp1, U30382; Shcherban et al., 1995), and Arabidopsis (At-Exp2, U30481; Shcherban et al., 1995; Fig. 1B). This class of expansins appears phylogenetically to be distinct from the tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) expansins expressed during fruit development and ripening (LeExp4 and LeExp1; Rose et al., 1997; Brummell et al., 1999) or expressed early in the emergence of leaf primordia (LeExp18; accession no. AJ004997; Reinhardt et al., 1998). Although FaExp2 is ripening regulated in strawberry fruit, it is more distantly related to the tomato ripening-regulated expansin LeExp1 (52%), and is more closely related to a tomato expansin, LeExp5 (63%), which is expressed in green fruit but not in ripening fruit (Brummell et al., 1999). These results suggest that ripening-associated expansins do not share a high degree of sequence relatedness and their function cannot be identified based on their primary structure.

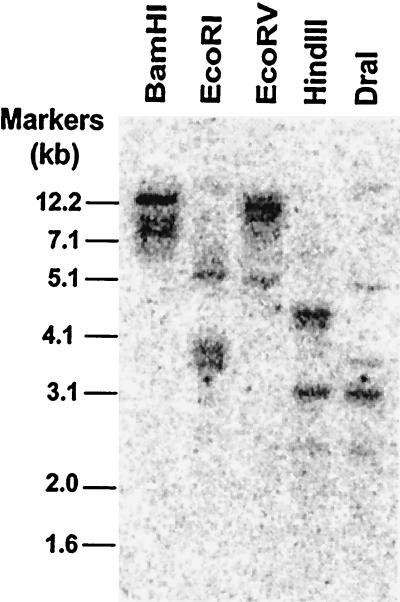

Genomic DNA Gel-Blot Analysis

A cDNA probe corresponding to a divergent region of FaExp2 (nt 2–151; probe 2) was prepared to analyze strawberry genomic DNA to assess the complexity of the expansin gene family related to FaExp2 (Fig. 2). The cDNA probe did not include restriction sites for any of the enzymes utilized (BamHI, EcoRI, EcoRV, HindIII, and DraI) and 80% (119/150 bases) of the probe was specific for FaExp2. Fragments with sizes ranging between 2.5 and 12 kb were detected by hybridization in each reaction. In all cases, more than one fragment hybridized to the FaExp2 sequence. Because expansin gene families have been described in tomato and other systems (Cosgrove, 1996; Brummell et al., 1999), it is possible that the 21 bases at the 3′ end of probe 2 recognized other expansin gene family members present in the strawberry genome. However, the hybridization pattern observed could be due to the octaploid genome of the cultivar we used (Chandler), suggesting that each parent contributed a FaExp2 gene distinguishable by restriction fragment polymorphism.

Figure 2.

Southern blot of genomic DNA from strawberry. Genomic DNA (20 μg per lane) was digested with the indicated restriction enzymes and hybridized with a 32P-labeled piece of FaExp2 probe (probe 2). The blot was washed three times for 20 min at 55°C with 0.2× SSC, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, and 0.01% (w/v) sodium PPi, and then exposed to a phosphor-imaging plate and analyzed with a phosphor imager.

Expression of FaExp2 and Strawberry Fruit Firmness

The expression of FaExp2 was analyzed by the mRNA abundance in vegetative tissues and in developing and ripening fruit. Probe 2, specific for FaExp2, was used to analyze the abundance of FaExp2 mRNA (Fig. 3). A strong hybridization signal was observed for a 1.2-kb mRNA from ripe strawberry receptacle tissue. However, FaExp2 mRNA was not detected in vegetative tissues (root, stem, leaves, and sepals), ovaries, or green achenes. This pattern suggests that the expression of FaExp2 is fruit specific, like the expression of LeExp1 in tomato (Rose et al., 1997).

Figure 3.

RNA gel-blot analysis of FaExp2 mRNA abundance in fruit and vegetative tissues. Total RNA (10 μg) from roots (R), stems (ST), leaves (L), sepals (S), ovaries (O), green achenes (GA), and ripe receptacle (RR) was electrophoresed and then hybridized with probe 2. Blots were washed three times for 20 min at 55°C with 0.2× SSC 0.1% (w/v) SDS, and 0.01% (w/v) sodium PPi. The blot was exposed to x-ray film with an intensifying screen at −80°C.

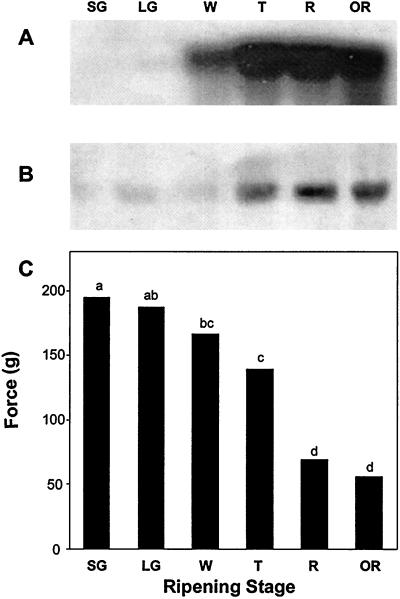

FaExp2 expression was analyzed by gel-blot hybridization to RNA from fruit throughout development and ripening. FaExp2 mRNA abundance was very low in green fruit and increased from the white to the ripe stage (Fig. 4A). A slight decrease in FaExp2 mRNA abundance was observed in overripe fruit. Protein recognized by the antibodies for LeExp1 became more abundant in the ripening fruit after the white stage (Fig. 4B). The protein detected by the LeExp1 antibodies had the expected molecular mass of 29 kD and was not observed in other tissues of the strawberry plant. Strawberry fruit firmness was evaluated by measuring the force necessary to compress the fruit 0.5 mm during the same ripening stages (Fig. 4C). Softening progressed steadily through ripening, and the rate of softening increased beginning at the white stage. Comparison of the pattern of FaExp2 mRNA abundance and protein accumulation (Fig. 4, A and B) with the fruit firmness profile (Fig. 4C) is consistent with the hypothesis that expansin may be involved in strawberry fruit softening.

Figure 4.

A, FaExp2 expression throughout strawberry fruit ripening. Northern-blot analysis of total RNA (10 μg) extracted from fruits at the following stages: small green (SG), large green (LG), white (W), turning (T), ripe (R), and overripe (OR). The blot was hybridized with probe 2. B, Western blot of total proteins extracted from ripening fruit were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by reaction with antibodies to LeExp1. C, Firmness evolution through strawberry fruit ripening. Fruits were compressed 0.5 mm and the maximum force reached was registered. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and the means compared by lsd(0.05) test. Letters above the bars indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences between data groups.

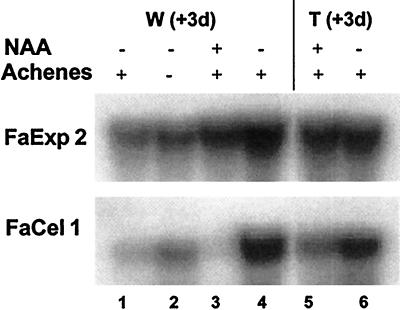

Effect of Auxin on FaExp2 Expression

Strawberry fruit ripening is non-climacteric; however, it is auxin regulated and the achenes are the endogenous source of auxin (Given et al., 1988). Auxin regulates the expression of several genes during strawberry fruit ripening (Reddy and Poovaiah, 1990; Manning, 1994). The expression of pectate lyase and cellulase, both enzymes related to cell wall metabolism, are repressed by auxin treatment in strawberry fruit (Medina-Escobar et al., 1997; Harpster et al., 1998). However, FaExp2 expression apparently was not greatly affected by auxin (Fig. 5). Elimination of achenes from half of the surface of white fruit for 3 d did not markedly affect FaExp2 mRNA abundance (Fig. 5, lanes 1 and 2). FaExp2 expression was compared with that in the control (untreated) halves (lane 1) of the deachened fruit. The same RNA gel blot was hybridized with a probe for FaCel1, an auxin-repressed gene (Harpster et al., 1998), and the expected increase of FaCel1 mRNA was observed in the deachened half of the fruit (lane 2). In another experiment, the achenes were maintained and NAA was applied to one-half of the fruit surface. There was a small reduction in FaExp2 mRNA abundance (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 4) in RNA from the treated fruit halves (lane 3) compared with the untreated control (lane 4) halves. The exogenous NAA treatment strongly inhibited FaCel1 expression, indicating that the treatment had been effective (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 4). However, the abundance of both FaExp2 and FaCel1 mRNA was greater in the fruit used in lanes 3 and 4 than in lanes 1 and 2, perhaps because of the presence of the achenes or because the fruit were slightly more advanced in the ripening process initially. Finally, exogenous NAA was applied to halves of turning fruit and essentially the same results were observed (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Effect of auxins on FaExp2 expression. Northern-blot analysis of total RNA (10 μg) extracted from white (W) or turning (T) fruits after 3 d at 20°C under different auxin conditions. These conditions resulted from combining the presence (+) or absence (−) of achenes with the application (+) or no application (−) of 1 mm NAA. The blot was hybridized with probe 2 for FaExp2. As a control for the auxin treatment, the same blot was stripped and subsequently hybridized with a probe for FaCel1, an auxin-repressed gene (Harpster et al., 1998).

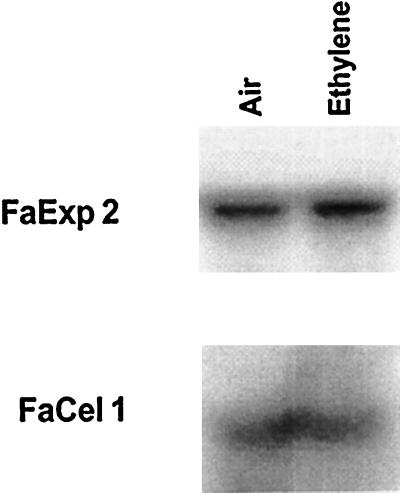

Effect of Ethylene over on FaExp2 Expression

As strawberry fruit are non-climacteric, ethylene does not influence their ripening behavior, although a possible minor influence of ethylene on strawberry fruit ripening cannot be completely eliminated. LeExp1, the tomato ripening-regulated expansin gene, is regulated by ethylene (Rose et al., 1997). White strawberry fruit treated with 10 μL L−1 of ethylene for 3 d did not show any difference in FaExp2 mRNA abundance compared with control fruits treated with air (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained after 1 d of treatment (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of ethylene on FaExp2 expression. Northern-blot analysis of total RNA (10 μg) extracted from white fruits maintained 3 d at 20°C in a continuous flow (20 L h−1) of humidified air in presence or absence of 10 μL L−1 of ethylene. The same blot was hybridized with probes for FaExp2 (probe 2) and FaCel1 (probe 3).

DISCUSSION

Ripening is comprised of metabolic processes that determine fruit quality and initiate senescence and fruit deterioration. Cell wall disassembly is a key ripening-associated metabolic event that determines the timing and extent of fruit softening and contributes to the ultimate deterioration of the fruit. Studies to elucidate the biochemical mechanisms of fruit softening have suggested that early events in melon fruit softening are associated with the disassembly of a tightly bound fraction of xyloglucan and that later softening is associated with pectin disassembly (Hadfield et al., 1998; Rose et al., 1998). This proposal is consistent with other studies of cell wall disassembly in ripening fruit (Maclachlan and Brady, 1992, 1994).

Although xyloglucan disassembly has been implicated as an early event in fruit softening, the enzymic basis for xyloglucan depolymerization is not well established. However, it has been suggested that xyloglucan metabolism may be regulated by substrate accessibility, and expansin proteins have been proposed to mediate enzymic accessibility of this substrate in ripening fruit (Rose and Bennett, 1999). In support of this hypothesis, a ripening-regulated expansin gene has been characterized in tomato (Rose et al., 1997). Strawberry differs significantly from tomato in that the fruit is derived from floral receptacle tissue rather than the ovary wall; also, strawberry fruit ripening is not ethylene regulated. Nevertheless, in both cases, fruit ripening is accompanied by rapid softening and disassembly of the polyuronide and hemicellulose polymer networks (Knee et al., 1977; Huber 1983, 1984). In the present study, we sought to determine whether, as in tomato, strawberry fruit softening during ripening is accompanied by expression of an expansin gene. As intact, untreated strawberry fruit soften and ripen, FaExp2 expression increases. Analysis of softening in de-achened or auxin-treated strawberry fruit has indicated that these fruit are delayed in ripening and remain firmer (Given et al., 1988), although the expression of FaExp2 is largely unaltered by these treatments. Therefore, FaExp2 expression is not the sole determinant of softening in strawberry fruit.

Our results demonstrated the presence of a ripening-regulated expansin gene in strawberry that exhibited a similar developmental pattern of expression as the tomato expansin gene LeExp1. However, FaExp2 encoded an expansin whose amino acid sequence is not closely related to LeExp1. Because no functional definition has been assigned to the expansin gene families, it is difficult to assign significance to the sequence differences between LeExp1 and FaExp2. If LeExp1 and FaExp2 represent functionally divergent expansins, then it is possible that the specific polymer substrate targeted for disassembly may differ in ripening tomato and strawberry fruit. Although we did not confirm the previous identification of other strawberry expansins with sequence similarity to LeExp1 (Rose et al., 1997), it is possible that they are present and also contribute to the cell wall disassembly process.

While tomato fruit ripening and LeExp1 gene expression are ethylene-regulated, the expression of FaExp2 was ethylene insensitive. All other ripening-regulated genes in strawberry have also been shown to be ethylene insensitive but auxin suppressed, with their expression activated when endogenous auxin levels decline below a critical threshold in developing fruit (Manning, 1994, 1998). Thus, it was surprising that FaExp2 expression was not strongly affected by auxin levels, because this result indicates that endogenous signals other than ethylene and auxin must operate to regulate gene expression in ripening strawberry. The FaExp2 gene may be a useful reporter gene to probe the nature of the non-climacteric signals that regulate its expression in ripening strawberry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. Dan Potter for his assistance and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This research was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program (grant no. 97–35304–4627). P.M.C. was supported by a fellowship from Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Argentina.

LITERATURE CITED

- Brummell DA, Harpster MH, Dunsmuir P. Differential expression of expansin gene family members during growth and ripening of tomato fruit. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;39:161–169. doi: 10.1023/a:1006130018931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H-T, Kende H. Expression of expansin genes is correlated with growth in deepwater rice. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1661–1671. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.9.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Plant cell enlargement and the action of expansins. BioEssays. 1996;18:533–540. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. Assembly and enlargement of the primary cell wall in plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:171–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg A, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AJ, McQueen-Mason S, Mandel T, Kuhlemeier C. Induction of leaf primordia by the cell wall protein expansin. Science. 1997;276:1415–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Given NK, Venis MA, Grierson D. Hormonal regulation of ripening in the strawberry, a non-climacteric fruit. Planta. 1988;174:402–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00959527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield KA, Rose JKC, Yaver DS, Berka RM, Bennett AB. Polygalacturonase gene expression in ripe melon fruit supports a role for polygalacturonase in ripening–associated pectin disassembly. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:363–373. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpster MH, Brummell DA, Dunsmuir P. Expression analysis of a ripening-specific, auxin-repressed endo-1,4-β-glucanase gene in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1307–1316. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Bleasby AJ, Fuchs R. Clustal V: improved software for multiple sequence alignment. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber DJ. Polyuronide degradation and hemicellulose modifications in ripening tomato fruit. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1983;108:405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Huber DJ. Strawberry fruit softening: the potential roles of polyuronides and hemicelluloses. J Food Sci. 1984;49:1310–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Knee M, Sargent JA, Osborne DJ. Cell wall metabolism in developing strawberry fruits. J Exp Bot. 1977;28:377–396. [Google Scholar]

- Lammeli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan G, Brady C. Multiple forms of 1,4-β-glucanase in ripening tomato fruits include a xyloglucanase activatable by xyloglucan oligosaccharides. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1992;19:137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Maclachlan G, Brady C. Endo-1,4-β-glucanase, xyloglucanase and xyloglucan endo-transglycosylase activities versus potential substrates in ripening tomatoes. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:965–974. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.3.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning K. Changes in gene expression during strawberry fruit ripening and their regulation by auxin. Planta. 1994;194:62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Manning K. Isolation of a set of ripening-related genes from strawberry: their identification and possible relationship to fruit quality traits. Planta. 1998;205:622–631. doi: 10.1007/s004250050365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason SJ, Cosgrove DJ. Disruption of hydrogen bonding between plant cell wall polymers by proteins that induce wall extension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6574–6578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason SJ, Cosgrove DJ. Expansin mode of action on cell walls: analysis of wall hydrolysis, stress relaxation, and binding. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:87–100. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason SJ, Durachko DM, Cosgrove DJ. Two endogenous proteins that induce cell wall extension in plants. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1425–1433. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.11.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueen-Mason SJ, Fry SC, Durachko DM, Cosgrove DJ. The relationship between xyloglucan endotransglycosylase and in vitro cell wall extension in cucumber hypocotyls. Planta. 1993;190:327–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00196961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Escobar N, Cárdenas J, Moyano E, Caballero JL, Muñoz-Blanco J. Cloning, molecular characterization and expression pattern of a strawberry ripening-specific cDNA with sequence homology to pectate lyase from higher plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;34:867–877. doi: 10.1023/a:1005847326319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford SJ, Timmis JN. Specific expression of an expansin gene during elongation of cotton fibres. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1398:342–346. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy ASN, Poovaiah BW. Molecular cloning and sequencing of a cDNA for an auxin-repressed mRNA: correlation between fruit growth and repression of the auxin-regulated gene. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;14:127–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00018554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt D, Wittwer F, Mandel T, Kuhlemeier C. Localized up regulation of a new expansin gene predicts the site of leaf formation in the tomato meristem. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1427–1437. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.9.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JKC, Bennett AB. Cooperative disassembly of the cellulose-xyloglucan network of plant cell walls: parallels between cell expansion and fruit ripening. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JKC, Hadfield KA, Labavitch JM, Bennett AB. Temporal sequence of cell wall disassembly in rapidly ripening melon fruit. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:345–361. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JKC, Lee HH, Bennett AB. Expression of a divergent expansin gene is fruit-specific and ripening-regulated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5955–5960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shcherban TY, Shi J, Durachko DM, Guiltinan MJ, McQueen-Mason SJ, Shieh M, Cosgrove DJ. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of expansins: a highly conserved multigene family of proteins that mediates cell wall extension in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9245–9249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Heijne A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan C, Wilkins TA. A modified hot borate method significantly enhances the yield of high-quality RNA from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) Anal Biochem. 1994;223:7–12. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]