Introduction

Esophageal cancer is an aggressive malignancy and a major cause of cancer-related deaths globally. In 2012, about 460,000 new cases of esophageal cancer were diagnosed worldwide, with 400,000 deaths attributed to the disease (1). In China, esophageal cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality, according to the China Cancer Registry, with approximately 270,000 new cases of esophageal cancer and about 200,000 deaths in 2013 (2). Surgery is still the most important and most effective way to treat resectable esophageal cancer. Despite advances in surgery and the development of multimodal therapy in recent years, patients with esophageal cancer continue to exhibit unfavorable clinical outcomes with a 5-year overall survival rate of less than 20% (3,4). Depth of carcinoma invasion and lymph node metastasis are the most important factors affecting esophageal cancer prognosis. Therefore, lymph node dissection is an essential part of radical surgery for esophageal cancer. Radical lymphadenectomy may help determine precise postoperative pathological staging, ensure the integrity and radicality of surgery, and more importantly, improve the survival of patients after surgery (5).

However, the indications, surgical approach, and extent of thoracic lymphadenectomy during esophagectomy for esophageal cancer are still under debate. Some studies suggested that radical lymphadenectomy could better control local lesions, remove undetectable micrometastases, and prolong patient survival (6-11), but others believed that the esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is a systemic disease (12) and radical lymphadenectomy would increase postoperative complications without prolonging the survival of patients (13-15). Therefore, in order to reach a consensus and to guide the clinical practice in China, the Esophageal Cancer Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association organized a group of experienced experts in the field to develop this consensus document.

Aim and scope of the consensus

The aim of the current consensus is to provide guidance to standardize mediastinal lymph node dissection in esophagectomy for esophageal cancer in China, to achieve accurate staging, reduce the local recurrence rate, and ultimately, to improve long-term survival. To achieve these goals, the committee took into consideration the experts’ clinical experiences and carefully reviewed existing evidence in the literature, most of the publications on this topic are from Chinese thoracic surgeons.

The scope of this consensus is limited to mediastinal lymph node dissection. Relevant contents about cervical and abdominal lymph node dissection involved in radical surgery for esophageal cancer will be described separately.

Chinese version of mediastinal lymph node map for thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

At present, both the lymph node maps of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) nomenclature (16-18) and the Japan Esophageal Society (JES) are commonly used in China for thoracic lymph nodes dissection in esophageal cancer (19,20). Major differences exist in N staging between the two systems; with the AJCC/UICC system, N staging is based on the number of lymph node metastases, while with the JES system, it is based on the region (i.e., the classified station) in which the metastatic lymph nodes are located. In clinical practice, AJCC/UICC N staging is simple and easy for surgeons and pathologists to apply. JES N staging may be better associated with the prognosis of esophageal cancer (21), but clinical application is relatively complicated. In Japan, this work is usually done by a surgeon (22). In addition, compared with the number of metastatic lymph nodes, the classification of metastatic lymph nodes does not always have a strong prognostic value. This is the main reason why JES standards are not widely used in countries outside of Japan.

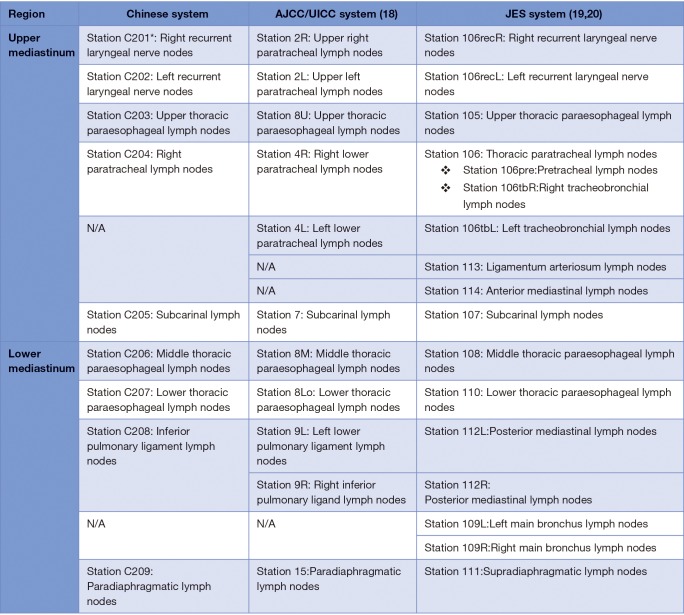

Taking into consideration the international acceptance and the clinical practice in China, the Esophageal Cancer Committee of the Chinese Anti-Cancer Association now proposes this Chinese system for the classification of thoracic lymph nodes in esophageal cancer. The present version aims to ensure consistency with the AJCC/UICC and the JES systems as much as possible, and to reflect the latest advances in mediastinal lymph node dissection for esophageal cancer. However, significant modifications have been made based on the evidence collected in China, since both the AJCC/UICC TNM classification (8th) and the JES classification (11th) have their own limitations (Figures 1,2). This consensus should be easy to use and will facilitate standardization and unification of mediastinal lymph node dissection in China. The Chinese version of the mediastinal lymph node map and its differences with the AJCC/UICC and JES systems are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the Chinese version of naming and grouping mediastinal lymph nodes with the AJCC/UICC and the JES systems for esophageal cancer. *, “C” represents Chinese standards and “2-” represents thoracic lymph nodes. AJCC, American Joint Committee of Cancer; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control; JES, Japan Esophageal Society.

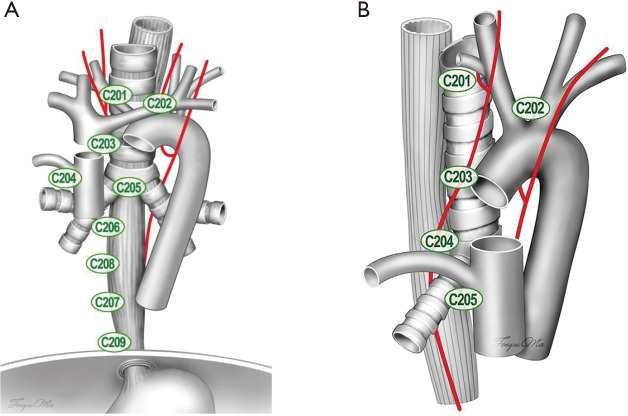

Figure 2.

Diagram of the Chinese version of naming and grouping of mediastinal lymph nodes in esophageal cancer: (A) anterior view; (B) right side view. “C” represents Chinese nomenclature, and “2-” represents thoracic lymph nodes. Station C201, right recurrent laryngeal nerve nodes; Station C202, left recurrent laryngeal nerve nodes; Station C203, upper thoracic paraesophageal lymph nodes; Station C204, right thoracic paratracheal lymph nodes; Station C205, subcarinal lymph nodes; Station C206, middle thoracic paraesophageal lymph nodes; Station C207, lower thoracic paraesophageal lymph nodes; Station C208, inferior pulmonary ligament lymph nodes; Station C209, paradiaphragmatic lymph nodes.

Recommendation 1: the current consensus represents the first Chinese version of naming and grouping mediastinal lymph nodes for esophageal cancer. It is in line with the current clinical practice in China, with the advantages of being concise, clear, and easy to use. It is recommended that the name of a specific mediastinal lymph node station be recorded by using “C” plus the relative number, e.g., C201, as the right recurrent laryngeal nerve nodes.

Thoracic lymphadenectomy procedures in radical esophagectomy for esophageal cancer

Lymph node metastasis is an independent prognostic factor for esophageal cancer. Frequency and distribution of nodal metastases vary greatly depending on the location, size, and depth of invasion of the primary tumor (23-27). The esophagus has a complex and widespread lymphatic drainage system; in addition to transmural lymphatic vessels that flow to the adjacent lymph nodes by penetrating the esophageal wall transversely, there are also abundant longitudinal lymphatic flows in the submucosal layer of the esophageal wall.

Surgical approaches to radical esophagectomy for esophageal cancer

The selection of the surgical approach greatly impacts the number and extent of lymph nodes that are dissected in radical surgery for esophageal cancer. The lower cervical and recurrent laryngeal nerve nodes are important drainage areas for thoracic esophageal cancer (28-30). Esophageal lymph node metastasis normally spreads along the bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerves beside the esophagus to cervical lymph nodes. Therefore, to ensure accurate pathological staging and complete tumor eradication, it is necessary to perform a radical dissection on the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerve nodes during thoracic surgery (31-33). Due to the obstacles presented by the aortic arch, left common carotid artery, and subclavian artery, it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to completely remove lymph nodes in the aforementioned areas via the traditional surgical approach using a left posterolateral thoracic incision. Approaches through a right thoracic incision (Ivor Lewis and McKeown procedures) can help overcome this shortcoming. Therefore, these two procedures have gradually become the preferred approaches for thoracic esophageal cancer (11,34-36). The Chinese Guidelines for Standardized Diagnosis and Treatment of Esophageal Cancer also recommended these procedures (37).

In recent years, minimally invasive esophagectomies (thoracoscopic or mediastinoscopic, or robotic-assisted) have been increasingly performed at home and abroad (38). These approaches are comparable to right thoracotomy in lymphadenectomy. No matter thoracotomy or minimally invasive surgery, similar standards in lymph node dissection should be followed to ensure the quality of surgery (39-42).

Recommendation 2: for radical esophagectomy with an intention to cure, a right transthoracic approach should be used for harvesting all the lymph nodes of the designated stations.

Number of lymph nodes removed in radical surgery for esophageal cancer

General information

According to the AJCC/UICC Staging of Cancers of the Esophagus (8th Edition), N staging is determined by the number of positive lymph nodes resected. Therefore, number of lymph nodes resected is critical to postoperative pathological N staging (43). That is, the more lymph nodes resected, the less likely that metastatic nodes be missed, and the higher accuracy of N staging (44-47). Thus, a reliable node-negative staging (N0 stage) requires a sufficient number of resected lymph nodes (47-51).

The Chinese Guidelines for Standardized Diagnosis and Treatment of Esophageal Cancer (37), the AJCC/UICC Staging of Cancers of the Esophagus (8th Edition), and the NCCN Guidelines for the Treatment of Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers [2016] all recommend that at least 11–15 nodes should be removed in radical surgery for esophageal cancer. Of course, this refers to the total number of nodes harvested in two- or three-field lymphadenectomy, not limited to the thoracic part of the dissection. Although a definitive number of nodes could not be decided for mediastinal dissection alone, systemic thoracic lymphadenectomy according to the proposed nodal map should always be performed for accurate N staging.

Recommendation 3: the mediastinal lymph nodes should be dissected as more as possible to ensure accurate pN staging and radical resection of the disease.

Special conditions

In clinical practice, multiple metastatic nodes may fuse into one, making it difficult to determine the exact number of lymph nodes. According to the AJCC/UICC Staging of Cancers of the Esophagus (8th Edition), fused nodes should be considered as one single node based on the principle that an uncertain stage will be determined as the earlier stage. Another common situation is that lymph nodes become fragmented during surgical dissection. If this is not documented in the pathology report, the number of metastatic nodes may be overestimated and this could lead to overstaging. Therefore, it is recommended that fragmented lymph nodes should be packed together and classified as one single node before it is sent for pathologic examination.

Neoadjuvant therapy has become the standard therapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer (52). However, little is known about the optimal number and extent of lymph nodes that should be removed after neoadjuvant therapy. Also, the number of lymph nodes removed has relatively low sensitivity for N staging in this scenario. Thus, the significance of lymphadenectomy after induction needs to be further confirmed. However, all of the suspected metastatic lymph nodes should be resected to evaluate the response of induction therapy and to help decide the ypStage according to the 8th UICC/AJCC staging system (53).

Extent of thoracic lymphadenectomy in radical surgery for esophageal cancer

In addition to the number of nodes dissected, the extent of mediastinal lymph node dissection is even more important to the outcome of esophagectomy (54-56). As mentioned earlier, regional lymph node identification and dissection should be based on the understanding of the anatomy of esophageal lymphatic drainage in all 9 stations of mediastinal lymph nodes as defined in the current consensus, and they should be dissected systemically in a radical esophagectomy.

Recommendation 4: all 9 stations of mediastinal lymph nodes (C201–C209) proposed in the current consensus should be dissected during radical surgery for esophageal cancer, especially the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerve nodes and para-esophageal nodes.

Lymphadenectomy-related complications and prevention of complications

Radical lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer involves extensive surgical dissection, and thus is associated with intensive trauma. In addition, preoperative co-morbidities, such as heart and lung diseases, that are commonly seen in esophageal cancer patients further increase the risk of postoperative complications. With the improvement in surgical techniques and instruments, anesthesia, and postoperative care, major complications are less frequent than they used to be but they still cannot be completely avoided.

Lymph nodes involved in esophageal cancer are widely spread in the thoracic cavity, from the entrance of the thorax to the diaphragm esophageal hiatus. Some of the lymph nodes are located deep in the mediastinum and adjacent to important organs. Precise dissection and careful exposure of these important neighboring organs, including the trachea, the aorta, pulmonary vessels, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and the thoracic duct, are mandatory to avoid unnecessary injury. Good exposure and lighting are always required to ensure a safe procedure.

The recurrent laryngeal nerves are prone to injury during lymphadenectomy due to their slenderness and frequent variation in anatomy. Adequate exposure of the nerve is mandatory when dissecting the lymph nodes that are alongside it. To better protect these nerves, the dissection should begin from the starting point where the right recurrent laryngeal nerve branches off from the vagus nerve, and the left recurrent nerve curves around the aortic arch. To preserve the blood supply to the nerve, extensive dissection of the epineurium should be avoided when resecting the surrounding lymph nodes. If energy devices, such as electric cautery or harmonic scalpel, are used, they should be kept at a safe distance away from the nerve to avoid thermal damage to the nerve. “Cold weapons”, such as scissors or blunt dissection instruments, are helpful in this area.

Special care should be taken not to injure the membranous trachea or the main bronchus when removing the paratracheal and subcarinal lymph nodes. Again, when energy devices are used, efforts should be made to avoid thermal damage to the tracheal membrane. The working blade of the harmonic scalpel should be kept away from the trachea and bronchus, and the device should be used with intermittent cooling to avoid overheating. En bloc resection of the lymph nodes is recommended. In addition to the oncological principle of radical resection, a fragmented lymph node or bleeding may obscure the surgical vision field and lead to inadvertent injury to the neighboring structures (57). Similarly, branches of the esophageal and bronchial arteries often extend under the lower pulmonary ligament, tracheal carina, aortic arch, and right subclavian artery. Therefore, these small artery branches should be carefully handled before removing the lymph nodes so as to avoid bleeding and ensuring clear dissection.

Chylothorax, which happens more often after extensive lymphadenectomy, is an annoying or even life-threatening problem. Tiny lymphatic vessels can be closed with a harmonic scalpel, but injuries to larger lymphatics or the thoracic duct are the major causes of refractory chylothorax. Therefore, it is recommended that the thoracic duct should be clearly exposed during mediastinal lymphadenectomy and carefully examined upon the completion of dissection. If an injury is suspected, thoracic duct ligation near the hiatus should be performed.

Pulmonary complications are the most common functional morbidity and a leading cause of mortality immediately after esophagectomy. During surgery, care should be taken to avoid stretching or compressing of the lung parenchyma. It has been suggested that preserving the bronchial arteries and the pulmonary branches of the vagus nerves during the dissection of the subcarinal nodes may help reduce pulmonary complications after surgery. Strict restriction of the amount and the rate of fluid input are extremely helpful in preventing the occurrence of pulmonary edema and respiratory insufficiency.

Recommendation 5: when ensuring the extent and number of lymph nodes involved in dissection, care should be taken to avoid any inadvertent injury associated with extensive lymphadenectomy.

Conclusions

Lymph node dissection is an important step of radical resection for esophageal cancer. An appropriate lymphadenectomy can be helpful in obtaining accurate pathological staging, reducing the local recurrence, and improving postoperative survival. Standardized and reasonable dissection of lymph nodes based on the characteristics of lymphatic metastasis and biological behavior of tumors is indispensable to improve the efficacy of esophageal cancer surgery.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87-108. 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Zeng H, et al. The incidence and mortality of major cancers in China, 2012. Chin J Cancer 2016;35:73. 10.1186/s40880-016-0137-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang SW, Zheng RS, Zuo TT, et al. [Mortality and survival analysis of esophageal cancer in China]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2016;38:709-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palladino-Davis AG, Mendez BM, Fisichella PM, et al. Dietary habits and esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus 2015;28:59-67. 10.1111/dote.12097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuan F, Qingfeng Z, Jia W, et al. Influence of Metastatic Status and Number of Removed Lymph Nodes on Survival of Patients With Squamous Esophageal Carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1973. 10.1097/MD.0000000000001973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tachimori Y, Ozawa S, Numasaki H, et al. Efficacy of lymph node dissection by node zones according to tumor location for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus 2016;13:1-7. 10.1007/s10388-015-0515-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1662-9. 10.1056/NEJMoa022343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Omloo JM, Lagarde SM, Hulscher JB, et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the mid/distal esophagus: five-year survival of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 2007;246:992-1000; discussion 1000-1. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815c4037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganesamoni S, Krishnamurthy A. Three-field transthoracic versus transhiatal esophagectomy in the management of carcinoma esophagus-a single--center experience with a review of literature. J Gastrointest Cancer 2014;45:66-73. 10.1007/s12029-013-9562-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mariette C, Piessen G. Oesophageal cancer: how radical should surgery be? Eur J Surg Oncol 2012;38:210-3. 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang ZQ, Deng HY, Hu Y, et al. Prognostic value of right upper mediastinal lymphadenectomy in Sweet procedure for esophageal cancer. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:3625-32. 10.21037/jtd.2016.12.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang WT, Chen WH. Current trends in extended lymph node dissection for esophageal carcinoma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2009;17:208-13. 10.1177/0218492309103332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies AR, Sandhu H, Pillai A, et al. Surgical resection strategy and the influence of radicality on outcomes in oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg 2014;101:511-7. 10.1002/bjs.9456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khullar OV, Jiang R, Force SD, et al. Transthoracic versus transhiatal resection for esophageal adenocarcinoma of the lower esophagus: A value-based comparison. J Surg Oncol 2015;112:517-23. 10.1002/jso.24024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ovrebo KK, Lie SA, Laerum OD, et al. Long-term survival from adenocarcinoma of the esophagus after transthoracic and transhiatal esophagectomy. World J Surg Oncol 2012;10:130. 10.1186/1477-7819-10-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:93-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Ferguson MK, et al. Cancer of the Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction: An Eighth Edition Staging Primer. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:36-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part II and III. Esophagus 2017;14:37-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part I. Esophagus 2017;14:1-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udagawa H, Ueno M, Shinohara H, et al. The importance of grouping of lymph node stations and rationale of three-field lymphoadenectomy for thoracic esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2012;106:742-7. 10.1002/jso.23122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang W, Kato H, Chen W, et al. Comparison of surgical management of thoracic esophageal carcinoma between two referral centers in Japan and China. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2001;31:203-8. 10.1093/jjco/hye043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Chen H, Xiang J, et al. Pattern of lymphatic spread in thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A single-institution experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:778-85; discussion 785-6. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng J, Wang WP, Dong T, et al. Refining the Nodal Staging for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Based on Lymph Node Stations. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:280-6. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.06.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang HX, Wei JC, Xu Y, et al. Modification of nodal categories in the seventh american joint committee on cancer staging system for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:216-24. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Q, Cai XW, Wu B, et al. Patterns of failure after radical surgery among patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: implications for the clinical target volume design of postoperative radiotherapy. PLoS One 2014;9:e97225. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen XL, Chen TW, Fang ZJ, et al. Patterns of lymph node recurrence after radical surgery impacting on survival of patients with pT1-3N0M0 thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Korean Med Sci 2014;29:217-23. 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.2.217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang F, Zheng Y, Wang Z, et al. Nodal Skip Metastasis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients Undergoing Three-Field Lymphadenectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:1187-93. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.03.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J, Liu Q, Wang Y, et al. Nodal skip metastasis is associated with a relatively poor prognosis in thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2016;42:1202-5. 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu J, Chai Y, Zhou XM, et al. Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:5084-9. 10.3748/wjg.14.5084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang ZQ, Wang WP, Yuan Y, et al. Left thoracotomy for middle or lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma: still Sweet enough? J Thorac Dis 2016;8:3187-96. 10.21037/jtd.2016.11.62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Tan LJ, Feng MX, et al. Feasibility and safety of radical mediastinal lymphadenectomy in thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2012;34:855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shan HB, Zhang R, Li Y, et al. Application of Endobronchial Ultrasonography for the Preoperative Detecting Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Lymph Node Metastasis of Esophageal Cancer. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137400. 10.1371/journal.pone.0137400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye T, Sun Y, Zhang Y, et al. Three-field or two-field resection for thoracic esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:1933-41. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li B, Xiang J, Zhang Y, et al. Comparison of Ivor-Lewis vs Sweet esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2015;150:292-8. 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duan X, Shang X, Tang P, et al. Lymph node dissection for Siewert II esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: a retrospective study of 136 cases. ANZ J Surg 2018;88:E264-7. 10.1111/ans.13980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Chinese Anti-cancer Assoication ECC. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal cancer. 2nd Edition. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li H, Hu B, You B, et al. Combined laparoscopic and thoracoscopic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: initial experience from China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125:1376-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin M, Shen Y, Wang H, et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve lymph node dissection in minimally invasive esophagectomy. J Vis Surg 2016;2:164. 10.21037/jovs.2016.10.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin J, Kang M, Chen C, et al. Thoracolaparoscopy oesophagectomy and extensive two-field lymphadenectomy for oesophageal cancer: introduction and teaching of a new technique in a high-volume centre. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;43:115-21. 10.1093/ejcts/ezs151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiu PW, Teoh AY, Wong VW, et al. Robotic-assisted minimally invasive esophagectomy for treatment of esophageal carcinoma. J Robot Surg 2017;11:193-9. 10.1007/s11701-016-0644-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye B, Zhong CX, Yang Y, et al. Lymph node dissection in esophageal carcinoma: Minimally invasive esophagectomy vs open surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:4750-6. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i19.4750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hou X, Wei JC, Fu JH, et al. Proposed modification of the seventh American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:337-42. 10.1245/s10434-013-3265-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu SG, Li FY, Zhou J, et al. Prognostic value of different lymph node staging methods in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:284-90. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin CS, Cheng CT, Liu CY, et al. Radical Lymph Node Dissection in Primary Esophagectomy for Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:278-86. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang HX, Xu Y, Fu JH, et al. An evaluation of the number of lymph nodes examined and survival for node-negative esophageal carcinoma: data from China. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1901-11. 10.1245/s10434-010-0948-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hu Y, Hu C, Zhang H, et al. How does the number of resected lymph nodes influence TNM staging and prognosis for esophageal carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:784-90. 10.1245/s10434-009-0818-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Hofstetter WL, et al. Esophageal Cancer: Associations With (pN+) Lymph Node Metastases. Ann Surg 2017;265:122-9. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao J, Yuan P, Ma H, et al. Log Odds of Positive Lymph Nodes Predicts Survival in Patients After Resection for Esophageal Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:424-32. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Z, Chen H, Yu W, et al. Number of negative lymph nodes is associated with survival in thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients undergoing three-field lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2857-63. 10.1245/s10434-014-3665-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang HL, Chen LQ, Liu RL, et al. The number of lymph node metastases influences survival and International Union Against Cancer tumor-node-metastasis classification for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus 2010;23:53-8. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1090-8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00040-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Kelsen DP, et al. Recommendations for neoadjuvant pathologic staging (ypTNM) of cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction for the 8th edition AJCC/UICC staging manuals. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:906-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peng J, Wang WP, Yuan Y, et al. Adequate lymphadenectomy in patients with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: resecting the minimal number of lymph node stations. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:e141-6. 10.1093/ejcts/ezw015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fu X, Liu Q, Luo K, et al. Lymph node station ratio: Revised nodal category for resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients. J Surg Oncol 2017;116:939-46. 10.1002/jso.24758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shao Y, Geng Y, Gu W, et al. Assessment of Lymph Node Ratio to Replace the pN Categories System of Classification of the TNM System in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1774-84. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu J, Hu Y, Xie X, et al. Subcarinal node metastasis in thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:423-7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]