Abstract

Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst (SEAC) is a rare cause of spinal cord compression. Bifocal location of thoracic and sacral SEACs is rarely reported in the literature. We report a case of thoracic spinal cord compression by SEAC associated with asymptomatic multiple sacral Tarlov cysts (TC). The surgical management and postoperative outcome of the patient are discussed. A 34-year-old woman was referred to the hospital for acute thoracic pain with a history of chronic long-standing back pain. She complained of walking difficulties. Neurological examination demonstrated incomplete spastic paraplegia with sensory level in T9. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large cystic formation from T7-11 and at the level of the sacrum. We performed laminectomies at the level of interest from T7-11. The cysts were dissected from the underlying dura after removal of the cerebrospinal fluid. We found nerve tissue in the cysts. We excised the cyst and preserved the nerve roots. Subsequently, a duraplasty was performed with autologous grafts from the lumbar fascia. The condition of the patient improved after surgery and he was recovering well at follow-up. Although the surgical treatment of TC is controversial, especially at the sacral lumbar level, decompression at the dorsal level in this case is indisputable.

Keywords: Extradural arachnoid cyst, Spinal cord compression, Tarlov cyst

Introduction

The spinal extradural arachnoid cyst (SEAC) is a rare cause of spinal cord compression. The etiology of SEAC remains unclear. They appear to be extradural outpouchings of arachnoid membranes that communicate with the intraspinal subarachnoid space through small defect in the dura.7,10,17) Tarlov cyst (TC) are predominantly found at the lumbosacral level of the spine but they are known to exist at all levels of the spine. Bifocal location of SEACs, thoracic and sacral, is exceedingly rarely reported in the literature. Here in we report a case of thoracic spinal cord compression by SEAC associated with asymptomatic multiple sacral cysts. The surgical management and postoperative outcome are discussed.

Case Report

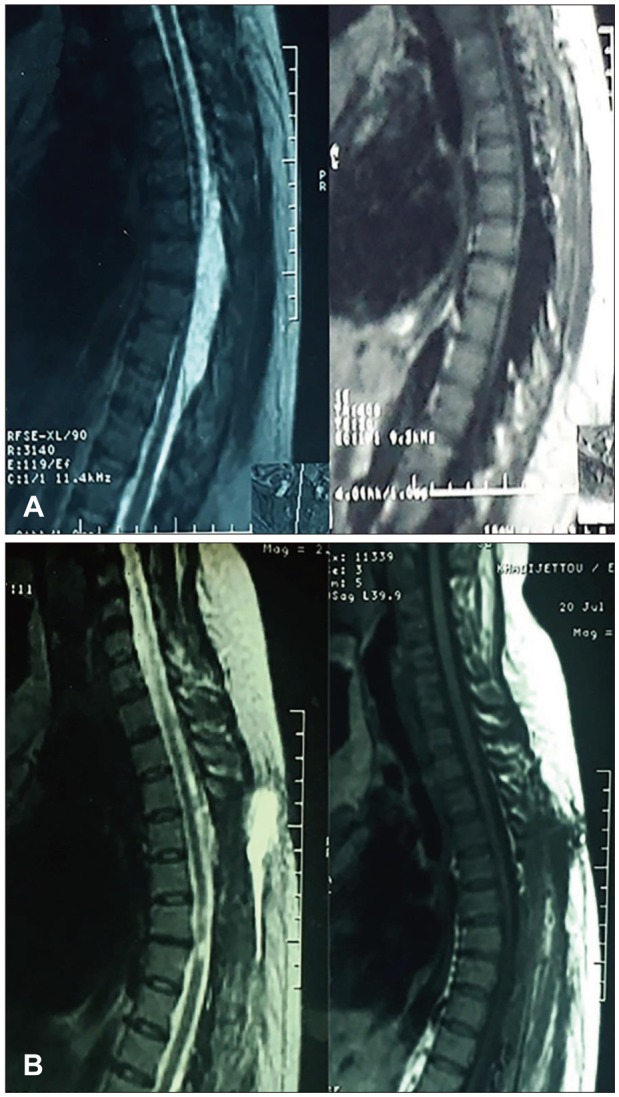

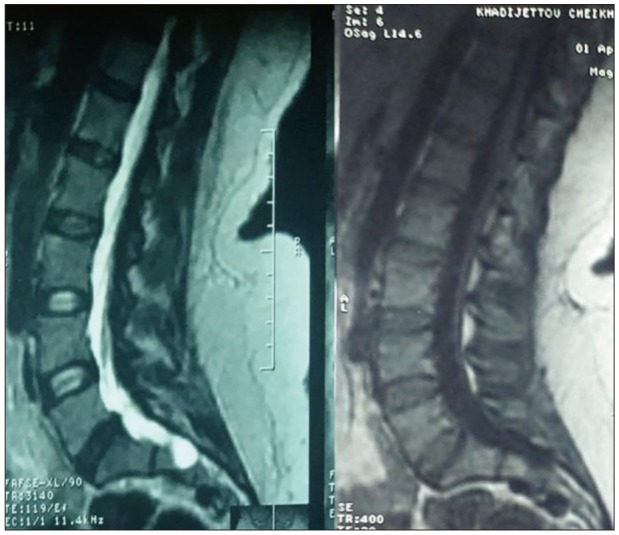

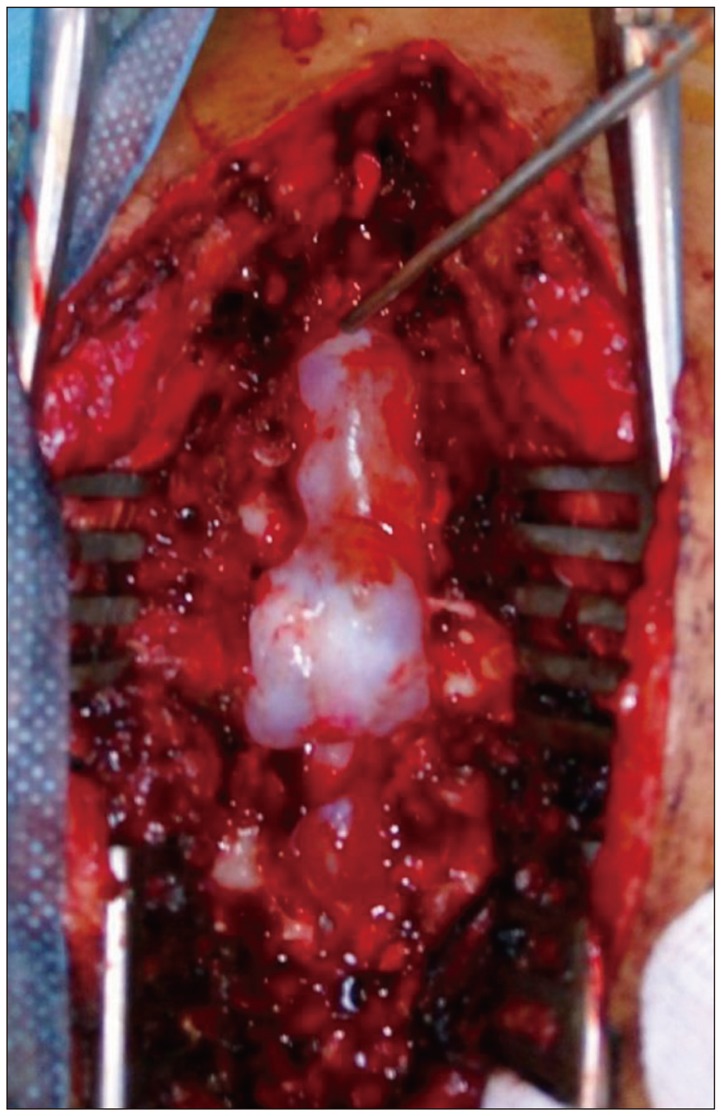

A 34-year-old woman with no history of trauma was referred to the emergency department for acute thoracic pain superimposed on a background of chronic long-standing back pain. The patient was complaining of walking difficulties. Neurological examination demonstrated an incomplete spastic paraplegia, grade 2 motor power in both lower limbs, with sensory level in T9, with pyramidal syndrome in the inferior limbs bilateral plantar extension responses, with hyperreflexia of both Achilles tendons reflexes were present. Sensory, bladder, and bowel functions were unremarkable. Imaging a spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed and revealed a large cystic formation compressing dorsal side of thecal sac from T7–11 (Figure 1) and at the level of the sacrum (Figure 2). The cysts were isointense to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted ones with peripheral contrast enhancement. Based on the imaging findings, a diagnosis of SEAC was suspected. For spinal cord decompression, we did laminectomies at the level of interest from T7–11 exposing the SEACs. The dura matter was exposed and then we found three SEACs (Figure 3). The cysts were dissected carefully from the underlying dura after removal of the CSF. We found nerve tissue in the cysts. It was possible to identify during surgery the location of the defects making the communication between the dura and the cysts. These defects were located on the right side of each cyst connecting with each other. The lesion was situated in close vicinity to the dorsal root ganglion of T9 to 11. We completely excised the cyst and preserved the nerve roots at the end of the surgery. Then, a duraplasty was performed to close the defects with autologous grafts from the patient's lumbar fascia. Following the complete removal of the cyst, Valsalva maneuver was performed. There was no evidence demonstrating CSF leakage. Regression of the symptoms, primarily the gait impairment, occurred after surgery and was still doing well at 6 months follow-up.

FIGURE 1. (A) Sagittal turbo spin echo (TSE) T2-weighted image (WI) and T1-WI magnetic resonance images showing at the T9 to T11 vertebral levels. Note the compression of the spinal cord. (B) Sagittal postoperative TSE T2-WI and T1-WI show total the spinal extradural arachnoid cysts.

FIGURE 2. Sagittal turbo spin echo T2-weighted image (WI) and T1-WI magnetic resonance image showing at the sacral lumbar Taralov cysts.

FIGURE 3. Intraoperative image: total laminectomy T7 to T11 level exposing the spinal extradural arachnoid cysts.

Discussion

SEACs have been rarely reported and reviewed in the literature. The origin of SEAC is uncertain. A congenital etiology has been put forward for these cysts, involving either congenital diverticula of the dura or arachnoid herniation through a congenital dural defect.10)

Nabors et al.8) classified these SEACs into three types:

Type 1: Extradural meningeal cysts that contain non-neural tissue subdivided into extradural cysts (Type 1A) and sacral meningoceles (Type 1B)

Type 2: Extradural meningeal cysts that contain neural tissue (Type 2, TC)

Type 3: Intradural meningeal cysts.

The present case corresponds to a perineurial cysts and would fit into Type 2 (TC). The TC are pathological formations located in the space between the perineurium and endoneurium of the spinal posterior nerve root sheath at the dorsal root ganglion (DRG). It is commonly attributed to inflammation within the nerve root sheath, or traumatic dural lacerations with hemorrhage followed by cystic degeneration,3,15,16) congenital diverticula, and hydrostatic CSF pressure. The author argues that an increase in CSF pressure forces the CSF into the normally obliterated perineural space to explain symptomatic fluctuations observed during the preoperative and postoperative course in patients with TC.3,6,9,13,14)

The perineurial cysts are meningeal dilations of the posterior spinal nerve root sheath that most often affect sacral roots and can cause a progressive painful radiculopathy or a symptomatology of medial compression as in our case. The TC are most commonly diagnosed by lumbosacral MRI and can often be demonstrated by computerized tomography (CT) myelography to demonstrate communication with the spinal subarachnoid space. MRI methods that detect CSF flow can identify the pulsating turbulent flow void of a defective site in most cases but the lack of the communication has also been reported in few cases.4)

The standard treatment for SEACs remains unclear. Some authors recommend conservative non-surgical management of SEACs and reported good outcomes. However, if the patient suffers from neurological deficits caused by spinal cord or radicular compression due to a growing SEAC, then the surgical procedure in our view becomes mandatory. There is a consensus among investigators to endeavor to repair the dural defect during the surgery of a SEAC.17) Although CT myelography and MRI are useful tools, the final diagnosis of a TC is not a radiological diagnosis; rather, it is a histopathological diagnosis,1) in our cases, the diagnosis of SEACs was made during surgery. We found nerve tissue within the cysts. To explain the pathophysiology of cyst enlargement, the active fluid secretion theory and pulsatile CSF dynamic theory have been put forward. If pulsatile CSF is “injected“ into the cyst to the cyst via a ball valve mechanism and the pressure is lowered, the outlet will be closed at the neck of the cyst7,12) unidirectional flow. According to the Laplace law, the body of the cyst exerts a force on the neck that is sufficient to close the communication, because its radius and wall tension are greater. This mechanism then may allow further enlargement, with persistent CSF pulsations.4,5) The presence or absence of a check-valve mechanism is very important in determining the need for surgical intervention for sacral meningeal cysts.2)

A TC may enlarge and becomes symptomatic and then requires treatment. In our cases, the sacral TC were asymptomatic and did not require intervention but the cysts at the dorsal thoracic level were symptomatic and responsible for spinal cord compression. This myelopathy would be secondary change of long standing spinal cord compression made by slowly growing cyst.4) Many surgical procedures were reported including lumbar CSF drainage either by puncture or shunting and CT-guided cyst aspiration either with or without infusion of fibrin glue. Many microsurgical techniques have been used to treat TC like cyst fenestration, cyst imbrication, cyst resection, clip remodeling of cyst walls, and free muscle flap.9,18) Asamoto et al.2) reported a technique of eliminating the presumed ball-valve mechanism of partially or intermittently communicating meningeal cysts by effectively opening the CSF fistula to facilitate two-way CSF flow and emptying of the cyst fluid.11)

The double location at the sacral and dorsal level of TC is rarely described in the literature. It is important to keep in mind that prior to any clinical presentation of spinal cord compression, radiological exploration is required. Although the surgical treatment of TC is controversial, especially at the sacral lumbar level, the surgical management of The SEAC caused spinal cord compression is indisputable as in the present case, where the evolution was favorable.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Acosta FL, Jr, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Schmidt MH, Weinstein PR. Diagnosis and management of sacral Tarlov cysts. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E15. doi: 10.3171/foc.2003.15.2.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asamoto S, Fukui Y, Nishiyama M, Ishikawa M, Fujita N, Nakamura S, et al. Diagnosis and surgical strategy for sacral meningeal cysts with check-valve mechanism: technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013;155:309–313. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1550-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantore G, Bistazzoni S, Esposito V, Tola S, Lenzi J, Passacantilli E, et al. Sacral Tarlov cyst: surgical treatment by clipping. World Neurosurg. 2013;79:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim IS, Hong JT, Son BC, Lee SW. Noncommunicating spinal extradural meningeal cyst in thoracolumbar spine. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;48:534–537. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2010.48.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu JK, Cole CD, Kan P, Schmidt MH. Spinal extradural arachnoid cysts: clinical, radiological, and surgical features. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22:E6. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lombardi G, Morello G. Congenital cysts of the spinal membranes and roots. Br J Radiol. 1963;36:197–205. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCrum C, Williams B. Spinal extradural arachnoid pouches. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:849–852. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nabors MW, Pait TG, Byrd EB, Karim NO, Davis DO, Kobrine AI, et al. Updated assessment and current classification of spinal meningeal cysts. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:366–377. doi: 10.3171/jns.1988.68.3.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naderi S. Surgical approaches in symptomatic tarlov cysts. World Neurosurg. 2016;86:20–21. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nayak R, Chaudhuri A, Sadique S, Attry S. Multiple spinal extradural arachnoidal cysts: An uncommon cause of thoracic cord compression. Asian J Neurosurg. 2017;12:321–323. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.150004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potts MB, McGrath MH, Chin CT, Garcia RM, Weinstein PR. Microsurgical fenestration and paraspinal muscle pedicle flaps for the treatment of symptomatic sacral tarlov cysts. World Neurosurg. 2016;86:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohrer DC, Burchiel KJ, Gruber DP. Intraspinal extradural meningeal cyst demonstrating ball-valve mechanism of formation. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:122–125. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.1.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber F, Haddad B. Lumbar and sacral cysts causing pain. J Neurosurg. 1951;8:504–509. doi: 10.3171/jns.1951.8.5.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strully KJ, Heiser S. Lumbar and sacral cysts of meningeal origin. Radiology. 1954;62:544–549. doi: 10.1148/62.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarlov IM. Perineurial cysts of the spinal nerve roots. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1938;40:1067–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarlov IM. Cysts, perineurial, of the sacral roots; another cause, removable, of sciatic pain. J Am Med Assoc. 1948;138:740–744. doi: 10.1001/jama.1948.02900100020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo JB, Son DW, Kang KT, Lee JS, Song GS, Sung SK, et al. Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2016;12:185–190. doi: 10.13004/kjnt.2016.12.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Sun Y, Huang X, Luan W. Management of symptomatic sacral perineural cysts. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]