Abstract

Objective

The objective of this article is to evaluate the relationship between off-hours hospital admission (weekends, public holidays or nighttime) and mortality for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGIH).

Methods

Medline, Embase, Scopus, and the Chinese Biomedical Literature were searched through December 2016 to identify eligible records for inclusion in this meta-analysis. A random-effects model was applied.

Results

Twenty cohort studies were included for analysis. Patients with UGIH who were admitted during off-hours had a significantly higher mortality and were less likely to receive endoscopy within 24 hours of admission. In comparison to variceal cases, patients with nonvariceal bleeding showed a higher mortality when admitted during off-hours. However, for studies conducted in hospitals that provided endoscopy outside normal hours, off-hours admission was not associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Conclusion

Our study showed a higher mortality for patients with nonvariceal UGIH who were admitted during off-hours, while this effect might be offset in hospitals with a formal out-of-hours endoscopy on-call rotation.

Keywords: Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, off-hours, meta-analysis

Key summary

- 1. Summarize the established knowledge on this subject

- Day of admission may be an important predictor for patient outcome.

- There is no consensus about “off-hours effect” for patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

- 2. What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

- Off-hours admission is associated with increased mortality as well as a delayed endoscopic intervention.

- The increased risk of mortality was not observed among hospitals with an off-hours endoscopy on-call rotation.

- Efforts should focus on improving clinical care and availability of endoscopy regardless of time of hospital admission.

Introduction

Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (UGIH) is a common medical emergency, with an annual incidence of 160 per 100,000 population in the United States of America (USA).1 Previous studies indicated that patients with UGIH who were admitted to the hospital during off-hours (weekends and public holidays) had a higher mortality rate than those admitted during regular hours.2–4 However, inconsistent results were also reported.5–7 Our recent retrospective analysis showed that holiday admission was not associated with increased mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding in Hong Kong.8 This might be attributed to the close proximity of patients to hospitals for the timely management of UGIH.

Evaluating the “off-hours effect” on patient outcomes in GI bleeding remains controversial. We thus conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis with the primary aim of investigating the association between hospital admission time (off-hours vs regular hours) and mortality for patients with UGIH.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and was reported following the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology recommendations.

Search strategy

Our search strategy is detailed in Supplementary Appendix 1. Medline, Embase, Scopus, and the Chinese Biomedical Literature were searched through December 2016 to identify literature describing the association between hospital admission time and clinical outcomes for patients with UGIH. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was consulted to determine if studies were missed. We also manually checked references listed in relevant studies to identify any article not identified in the original search. The possible unpublished trials were searched on ClinicalTrials.gov (up to July 2017), The International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Register scheme, and The International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal. A librarian was consulted to supervise the search process and access to the database.

Study selection

This study included all literature that compared the outcomes of patients with UGIH who were admitted during off-hours against regular hours. Non-original articles and duplicate publications were excluded. Discrepancies on decisions were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

For mortality, early endoscopy and endoscopic treatment, the need for surgery and angiographic embolization, and rebleeding rate, we extracted the occurred number or raw proportion in each cohort, and the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidential interval (CI). We recorded the length of stay (LOS) by extracting mean with standard deviation. Authors were contacted for additional or missing information if necessary. One investigator extracted the information, and another one verified it. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) to evaluate the quality of included studies. The maximum score for a cohort study is 9, and scores of 0 to 3, 4 to 6, and 7 to 9 were considered low, moderate, and high quality, respectively.9 Two of us did the quality assessment independently, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Outcome definition and subgroup analysis

The primary outcome was mortality. We used in-hospital mortality data as preferences, but if they were not available, we then extracted 30-day mortality. Early endoscopy and endoscopic treatment, the need for surgery and angiographic embolization, rebleeding rate, and LOS were analyzed as the secondary endpoints. Pre-designed subgroup analyses were conducted to discuss the relationship between etiology of hemorrhage, region, and the availability of endoscopy during off-hours and clinical outcomes.

Statistical analysis

For mortality, early endoscopy and endoscopic treatment, the need for surgery and angiographic embolization, and rebleeding rate, we retrieved the adjusted OR and the corresponding 95% CI for analysis. If the adjusted estimates were not available, we used unadjusted ones. For LOS, we imputed the weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CI from mean and standard deviation. The random-effects model was applied in this meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was assessed by I2 statistic and Q test. To explore possible publication bias, we examined the asymmetry of funnel plots using the Egger regression test. The trim and fill approach was also used to adjust the estimated effect size for the potential publication bias. We performed sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of the results. We used STATA 12.0 for statistical analysis, and a p value lower than 0.05 indicated significance.

Results

Description of the eligible studies

The results of our literature search are illustrated by the flowchart in Figure 1. Twenty studies with a total of 793,158 cases of UGIH met the inclusion criteria, and were finally included for meta-analysis. Table 1 summarizes the details of recruited studies. The year of publication ranged from 1993 to 2016. Five studies were carried out in Asia (Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Saudi Arabia),8,10–13 six in North America (USA),4,6,14–17 and nine in Europe (Italy, the Netherlands, Serbia, and the United Kingdom).2,3,5,7,18–22 Six studies reported patients with UGIH caused by peptic ulcer,8,10,12,19,20,22 one study included patients with bleeding gastroduodenal angiodysplasia,17 three demonstrated the sources of bleeding were from the esophagus varix,11,13,15 and 10 studies included patients with both variceal and nonvariceal UGIH.2,3,5–7,14,16,18,21,22 Most recruited studies defined the “off-hours” as weekends only,4–7,11,13–17,21 while four studies defined it as weekends and public holidays;3,8,12,18 one study defined it as weekends and nighttime,20 and one study defined it as nighttime only.19 Three studies reported results by comparison to weekend admissions as well as nighttime admissions.2,10,22 In order to avoid repeated calculation, we combined only weekend admissions for the current analysis. All studies were designed as cohorts; 17 were retrospective3–8,10–18,21,22 and three were prospective.2,19,20 We contacted the authors of one of the included studies and obtained additional information for our analysis.21 Seven studies analyzed the same administrative database (the United States National Inpatient Sample (NIS));4,6,15–17,23,24 we finally included five with the most recent year of publication to avoid overlapping sets of patients.4,6,15–17 NOS assessment indicated that seven cohorts had moderate quality and 13 cohorts had high quality (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart for selection of eligible studies.

GI: gastrointestinal.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| First author, yearref | Region | Year of patient cohort | Cause for UGIH | Total admissions | Definition of off-hours | Study design | Outcomes measured | Adjusted variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammed, 201622 | UK | April 2008 ∼ June 2012 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 507 | Weekends, or nighttime | Retrospective | 30-day mortality | |

| Serrao, 201617 | USA | 2000 ∼ 2011 | Gastroduodenal angiodysplasia | 85,971 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality; delay endoscopy; LOS; surgery rate | Demographic and covariate variables |

| Weeda, 201716 | USA | 2010 ∼ 2012 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 119,353 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality; LOS | Age (75 years), gender, race, primary payer, the presence of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-29 comorbidities (excluding peptic ulcer disease), and hospital teaching status/location, region and bed size |

| Ahmed, 201521 | Scotland | January 2000 ∼ October 2009 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 60,643 | Weekends | Retrospective | 30-day mortality; LOS | |

| Al-Qahatani, 201513 | Saudi Arabia | January 2005 ∼ July 2013 | Variceal | 937 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality; endoscopy within 24 hours; need for surgery; rebleeding; LOS | |

| Wu, 201412 | Taiwan | January 2009 ∼ March 2011 | Peptic ulcer | 744 | Weekends + public holiday | Retrospective | 30-day mortality, need for surgery, rebleeding rate, LOS | |

| Abougergi, 20146 | USA | January 2009 ∼ December 2009 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 202,259 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality, endoscopy within 24 hours, need for angiographic embolization, LOS | Age, sex, race/ethnicity, median yearly income, patient's comorbidities, hospital location, geographic region, hospital teaching status, and hospital bed size |

| Tufegdzic, 20145 | Serbia | January 2002 ∼ January 2012 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 493 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality, need for surgery, rebleeding rate, LOS | Weekend admission, age, symptoms and treatment |

| Haas, 201214 | USA | January 2008 ∼ October 2008 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 174 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital and 30-day mortality, need for surgery, LOS | |

| de Groot, 20122 | the Netherlands | October 2009 ∼ September 2011 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 571 | Weekends + holiday, or evening + night | Prospective | 30-day mortality, need for s urgery, rebleeding rate | Age, GI cancer, DM, rectal blood loss, collapse, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, urea, intervention needed, pre- and post-endoscopic blood transfusion |

| Youn, 201210 | South Korea | January 2007 ∼ December 2009 | Peptic ulcer | 388 | Weekends, or nighttime | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality, need for surgery and angiographic embolization, rebleeding rate, LOS | Age |

| Tsoi, 20118 | Hong Kong | January 1993 ∼ December 2005 | Peptic ulcer | 8222 | Weekends + public holiday | Retrospective | 30-day mortality, need for surgery | Waiting time, age, hemodynamic status, and comorbid illness |

| Byun, 201211 | South Korea | January 2005 ∼ February 2009 | Variceal | 294 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality, rebleeding rate | |

| Jairath, 20117 | UK | May 2007 ∼ July 2007 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 6749 | Weekends | Retrospective | 30-day mortality, endoscopy within 24 hours, need for surgery and angiographic embolization, rebleeding rate, LOS | Clinical Rockall score, hematemesis, melena, hemoglobin and urea concentration on admission, use of aspirin, NSAID, proton pump inhibitors, gender, variceal bleeding, peptic ulcer bleeding, whether received endoscopy during 24 hours, admission status |

| Button, 20113 | UK | April 1999 ∼ March 2007 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 24,421 | Weekends + public holiday | Retrospective | 30-day mortality | Age, gender, malignancies, circulatory diseases, renal failure, diabetes, COPD and liver disease |

| Myers, 200915 | USA | January 1998 ∼ December 2005 | Variceal | 36,734 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality | Age, sex, race, health insurance, liver-related variables, comorbidities, hospital and admission characteristics, year and procedures |

| Shaheen, 20094 | USA | January 1993 ∼ December 2005 | Peptic ulcer | 237,412 | Weekends | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality, need for surgery | Age, sex, race, health insurance, comorbidities, hospital and admission characteristics, year and procedures |

| Schmulewitz, 200518 | UK | January 2001 ∼ December 2001 | Variceal + nonvariceal | 584 | Weekends + public holiday | Retrospective | In-hospital mortality | Age, sex |

| Parente, 200519 | Italy | July 2001 ∼ July 2003 | Peptic ulcer | 272 | Night | Prospective | 30-day mortality, need for surgery, rebleeding rate | Age, sex, Rockall and Forrest score, blood transfusion, and experience of endoscopists |

| Choudari, 199320 | UK | October 1991 ∼ September 1992 | Peptic ulcer | 114 | Weekends + night | Prospective | 30-day mortality, need for surgery, rebleeding rate |

UGIH: upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage; DM: diabetes mellitus; GI: gastrointestinal; LOS: length of hospital stay; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; UK: United Kingdom; USA: United States of America.

Primary outcome: Mortality

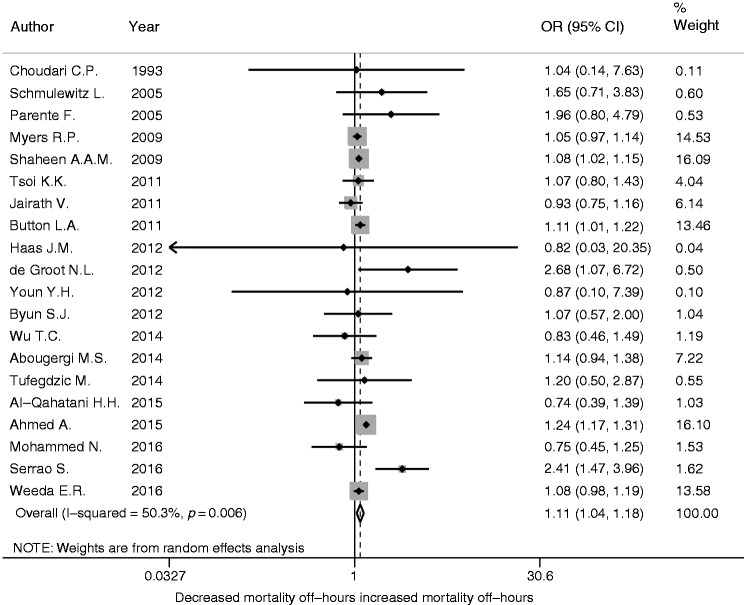

Twenty studies reported mortality. Of these, 10 studies reported in-hospital mortality,4–6,10,11,13,15–18 nine reported 30-day mortality,2,3,7,8,12,19–22 and one reported both.14 The result of meta-analysis showed that patients who were admitted during off-hours had significantly higher overall mortality compared to those admitted during regular hours, with a pooled OR of 1.11 (Figure 2; 95% CI 1.04–1.18, p = 0.006). Off-hours admission was also associated with a higher in-hospital mortality (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02–1.16, p = 0.009), while 30-day mortality showed loss of significance (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.98–1.24, p = 0.116).

Figure 2.

Comparison of overall mortality for patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage between off-hours admission and regular hours admission. Forest plot of 20 cohorts.

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Subgroup analyses were performed based on the upfront design (Table 2). In comparison to variceal patients, patients with nonvariceal bleeding had significantly higher overall and in-hospital mortality when admitted during off-hours (for overall mortality, OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.23, p = 0.015; for in-hospital mortality OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.02–1.28, p = 0.025). Studies in North America also indicated a larger increase in mortality during off-hours (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.19, p = 0.019). But for studies that were conducted in hospitals with an on-call endoscopic service, no significant interaction between off-hours admission and increase in mortality was observed (overall 12615 UGIH patients; OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.84–1.22, p = 0.904). In addition, when analysis was restricted to the studies reporting adjusted mortality outcome, the increase in mortality for off-hours admission remained significant (adjusted OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.01∼1.17, p = 0.018 vs unadjusted OR 1.13, 95% CI 1.01∼1.27, p = 0.038).

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses for overall mortality.

| Subgroup | Number of cohorts | Total number of cases | OR | 95% CI | p value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. By source of bleeding | |||||

| Nonvariceal | 10 | 641,021 | 1.12 | 1.02 ∼ 1.23 | 0.22 |

| Variceala | 6 | 52,172 | 1.04 | 0.96 ∼ 1.12 | |

| 2. By region | |||||

| North America | 6 | 681,903 | 1.10 | 1.02 ∼ 1.19 | 0.01 |

| Asia | 5 | 10,585 | 0.98 | 0.79 ∼ 1.23 | |

| Europe | 9 | 100,670 | 1.14 | 1.00 ∼ 1.29 | |

| 3. By availability of endoscopy during off-hours | |||||

| With an off-hours rotation | 10 | 12,615 | 1.01 | 0.84 ∼ 1.22 | |

| 4. By outcome adjustment | |||||

| Unadjusted | 10 | 95,109 | 1.13 | 1.01 ∼ 1.27 | 0.003 |

| Adjusted | 10 | 698,049 | 1.09 | 1.01 ∼ 1.17 | |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Patients with variceal bleeding reported only as in-hospital mortality.

Secondary outcomes

1. Early endoscopy and endoscopic treatment

Four studies reported the proportion of endoscopy performed within 24 hours of admission.6,7,13,17 Patients with UGIH were less likely to receive early endoscopy when admitted during off-hours (Figure 3(a); OR 0.60, 95% CI 0.54–0.68; p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis indicated that both nonvariceal and variceal bleeding patients had less timely endoscopy during off-hours admissions (Table 3(a); for nonvariceal bleeding, OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.63–0.68, p < 0.001; for variceal bleeding, OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44–0.96, p = 0.029). In addition, studies in the USA and Europe indicated that patients with UGIH had a significantly delayed endoscopy during off-hours (Table 3(a); for USA, OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.64–0.68, p < 0.001; for Europe, OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.41–0.54, p < 0.001).

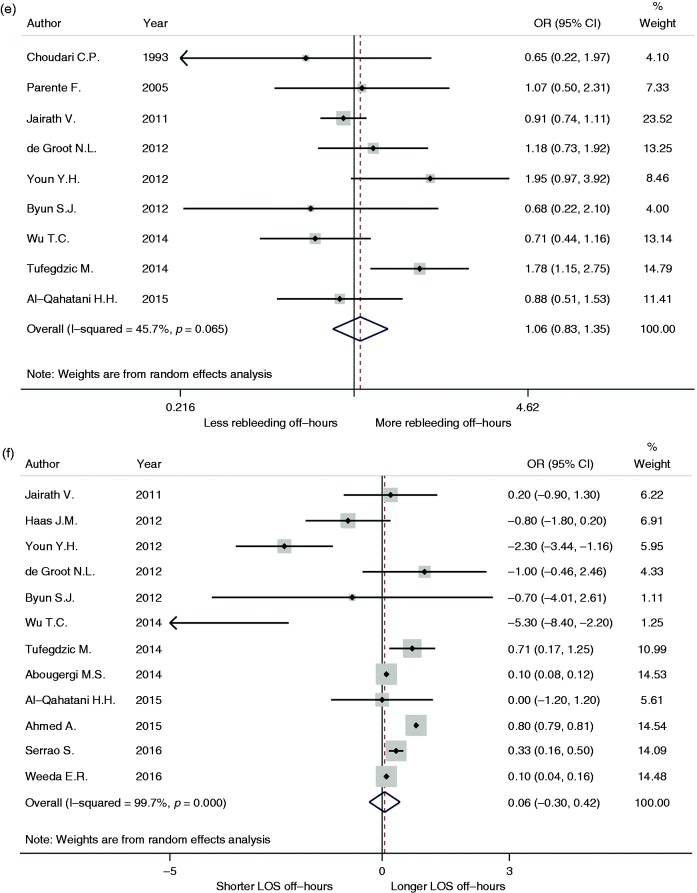

Figure 3.

Comparison of early endoscopy (a), endoscopic treatment (b), need for surgery (c), angiographic embolization (D), rebleeding rate (e), and length of hospital stay (LOS) (f) for patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage between off-hours admission and regular hours admission.

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses for early endoscopy (a), endoscopic treatment (b), need for surgery (c) and angiographic embolization (d), rebleeding rate (e), and length of hospital stay (f).

| Subgroup | Number of cohorts | Total number of cases | OR/WMD | 95% CI | p value for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Early endoscopya | |||||

| 1. By source of bleeding | |||||

| Nonvariceal | 2 | 284,979 | 0.66 | 0.63 ∼ 0.68 | 1.0 |

| Variceal | 2 | 4188 | 0.65 | 0.44 ∼ 0.96 | |

| 2. By region | |||||

| North America | 2 | 288,230 | 0.66 | 0.64 ∼ 0.68 | <0.001 |

| Asia | 1 | 937 | 0.61 | 0.34 ∼ 1.07 | |

| Europe | 1 | 6749 | 0.47 | 0.41 ∼ 0.54 | |

| 3. By availability of endoscopy during off-hours | |||||

| With an off-hours rotation | 1 | 937 | 0.61 | 0.34 ∼ 1.07 | |

| (b) Endoscopic treatmenta | |||||

| 1. By source of bleeding | |||||

| Nonvariceal | 3 | 199,510 | 0.98 | 0.92 ∼ 1.04 | 0.37 |

| Variceal | 2 | 3545 | 0.82 | 0.56 ∼ 1.20 | |

| 2. By region | |||||

| North America | 1 | 202,259 | 0.97 | 0.92 ∼ 1.03 | 0.93 |

| Asia | 2 | 682 | 1.07 | 0.55 ∼ 2.09 | |

| Europe | 2 | 6863 | 0.88 | 0.49 ∼ 1.56 | |

| 3. By availability of endoscopy during off-hours | |||||

| With an off-hours rotation | 2 | 682 | 0.88 | 0.49 ∼ 1.56 | |

| (c) Need for surgerya | |||||

| 1. By source of bleeding | |||||

| Nonvariceal | 7 | 333,123 | 1.09 | 0.94 ∼ 1.26 | 0.81 |

| Variceal | 1 | 937 | 0.88 | 0.45 ∼ 1.71 | |

| 2. By region | |||||

| North America | 3 | 323,557 | 1.09 | 1.03 ∼ 1.15 | 1 |

| Asia | 4 | 10,291 | 1.08 | 0.79 ∼ 1.49 | |

| Europe | 5 | 8199 | 1.08 | 0.67 ∼ 1.73 | |

| 3. By availability of endoscopy during off-hours | |||||

| With an off-hours rotation | 7 | 11230 | 1.07 | 0.82 ∼ 1.40 | |

| (d) Need for angiographic embolizationa | |||||

| 1. By source of bleeding | |||||

| Nonvariceal | 2 | 199,396 | 1.05 | 0.74 ∼ 1.48 | |

| 2. By region | |||||

| North America | 1 | 199,008 | 1.04 | 0.73 ∼ 1.48 | 0.85 |

| Asia | 1 | 388 | 1.32 | 0.15 ∼ 12.01 | |

| Europe | 2 | 7320 | 1.23 | 0.81 ∼ 1.86 | |

| 3. By availability of endoscopy during off-hours | |||||

| With an off-hours rotation | 1 | 388 | 1.32 | 0.15 ∼ 12.01 | |

| (e) Rebleeding ratea | |||||

| 1. By source of bleeding | |||||

| Nonvariceal | 5 | 1977 | 1.16 | 0.74 ∼ 1.80 | 0.38 |

| Variceal | 3 | 1265 | 0.98 | 0.55 ∼ 1.75 | |

| 2. By region | |||||

| Asia | 4 | 2363 | 0.96 | 0.61 ∼ 1.52 | 0.54 |

| Europe | 5 | 8199 | 1.12 | 0.82 ∼ 1.54 | |

| 3. By availability of endoscopy during off-hours | |||||

| With an off-hours rotation | 6 | 3128 | 1.12 | 0.76 ∼ 1.65 | |

| (f) Length of hospital stayb | |||||

| 1. By source of bleeding | |||||

| Nonvariceal | 4 | 308,571 | 0.11 | –0.03 ∼ 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Variceal | 4 | 15,404 | 0.36 | 0.21 ∼ 0.51 | |

| 2. By region | |||||

| North America | 4 | 407,757 | 0.13 | 0.05 ∼ 0.21 | <0.001 |

| Asia | 4 | 2363 | –1.86 | –3.83 ∼ 0.11 | |

| Europe | 4 | 81,647 | 0.80 | 0.79 ∼ 0.81 | |

| 3. By availability of endoscopy during off-hours | |||||

| With an off-hours rotation | 6 | 3418 | –1.06 | –2.41 ∼ 0.28 | |

OR: odds ratio.

WMD: weighted mean difference. CI: confidence interval.

Five studies reported the endoscopic treatment for patients with UGIH.6,7,10,11,20 However, the pooled results showed that the day of admission was not a predictor of endoscopic therapy (Figure 3(b); OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.92–1.02, p = 0.232). Subgroup analyses were also not statistically significant (Table 3(b)).

2. Need for surgery and angiographic embolization

Twelve studies reported surgery rate for patients with UGIH.2,4,5,7,8,10,12–14,17,19,20 Off-hours admission significantly increased the risk of surgical intervention (Figure 3(c); OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.02–1.17, p = 0.018). Subgroup analysis for studies in the USA also demonstrated that off-hours admission was associated with more surgical requirements (Table 3(c); OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.03–1.15, p = 0.002).

Four studies reported the need for angiographic embolization for patients with UGIH;2,6,7,10 however, the pooled effect did not show a significant correlation with off-hours admission (Figure 3(d); OR 1.12, 95% CI 0.89–1.42, p = 0.34).

3. Rebleeding rate

Nine studies reported the rate of rebleeding.2,5,7,10–13,19,20 However, it demonstrated that off-hours admission was not associated with a high risk of rebleeding for patients with UGIH (Figure 3(e); OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.83–1.35, p = 0.66).

4. LOS

Twelve studies reported LOS.2,5–7,10–14,16,17,21 We did not find significant difference in LOS between off-hours and regular hours admissions (Figure 3(f); WMD 0.06 day, 95% CI –0.30 to –0.42, p = 0.747). However, subgroup analysis indicated that patients with variceal bleeding had a longer LOS if admitted during off-hours (Table 3(f); WMD 0.36 day, 95% CI 0.21–0.51, p < 0.001). Studies in the USA and Europe also reported that off-hours admission was associated with an extension of hospital stay (Table 3(f); for USA, WMD 0.13 day, 95% CI 0.05–0.21, p = 0.001; for Europe, WMD 0.80 day, 95% CI 0.79–0.81, p < 0.001).

Sensitivity analysis and test for publication bias

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing each single cohort, as well as by restricting the admission time over weekends only, since most of the included patients were in cohorts where only weekends were considered for the off-hours period. It showed that the pooled result did not significantly alter except for the need for surgery. In addition, when including high-quality studies for analysis, only the result of LOS changed while the others remained robust.

Funnel plots were created to assess possible publication bias (Figure 4). Visual inspection of funnel plot for overall mortality appeared symmetric and the Egger test was not statistically significant. The trim and fill approach also demonstrated that the imputed estimate for overall mortality was the same as the primary analysis.

Figure 4.

Funnel plots for mortality (a), early endoscopy (b), endoscopic treatment (c), need for surgery (d) and angiographic embolization (e), rebleeding rate (f), and length of hospital stay (LOS) (g).

Discussion

The “weekend effect” has been reported for other medical emergencies such as acute myocardial infarction25 and pulmonary embolism.26 In the current systematic review and meta-analysis, we demonstrated that patients with UGIH who were admitted to the hospital during off-hours had a significantly higher overall mortality and a less timely endoscopy within 24 hours of admission. Compared to variceal patients, patients with nonvariceal bleeding appeared to be associated with significantly higher overall and in-hospital mortality during off-hours admissions. However, for hospitals that provided a formal endoscopic service outside normal working time, the odds of mortality for off-hours admission decreased. Results were robust to sensitivity analysis.

The current meta-analysis indicated that the odds of overall mortality would increase by 11% if patients with UGIH were admitted during off-hours. However, subgroup analysis revealed that the increase in mortality was observed only in North America while no effect was shown in Asia and Europe. One possible explanation for the difference in study results is that most studies in North America had a large sample size and were nationally representative by using the NIS database.4,6,15–17 The NIS database is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the USA. It represents a 20% stratified probability sample of all nonfederal acute care hospitals nationwide. Another possible explanation is the different definitions of outcome among studies. Mortality was in-hospital in all studies in North America, whereas 30-day mortality was reported in some studies in Asia8,12 and Europe.2,3,7,19–22 Thirty-day mortality includes all-cause deaths occurring only within 30 days of hospitalization and after being discharged from the hospital. For in-hospital mortality, all mortality will be counted, so long as the patient stays in the hospital. Hence, it is much broader in coverage than 30-day mortality. In fact, the current meta-analysis found that the off-hours admission was only associated with a higher in-hospital mortality rather than 30-day mortality. A third possible explanation is the different variables that were used for adjustment in each study.

The impact of early endoscopy on mortality for patients with UGIH remains uncertain. Lin et al. reported that early endoscopy within 12 hours of admission did not show outcome benefit for patients with active peptic ulcer bleeding.27 On the other hand, another study from Singapore demonstrated that endoscopy within 13 hours reduced mortality by 44% in patients with high-risk nonvariceal bleeding.28 Youn et al.10 also found that if endoscopy was performed within 24 hours of admission, the mortality due to peptic ulcer bleeding would be reduced to 1.8% as compared to 6%∼7% in previous reports. However, the sample size of these studies was relatively small; fewer than 1000 patients were included for analysis. There seems to be a strong correlation between timely endoscopic management and staff coverage in the hospital, especially the availability of on-call gastroenterologists or endoscopists during off-hours. In the current systematic review and meta-analysis, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on the availability of out-of-hours endoscopic service. Ten cohort studies were included; a total of 12,615 patients with UGIH were admitted to hospitals that provided a formal endoscopic service during off-hours. Results showed that the odds of overall mortality decreased by 10% for off-hours admission (1.01 vs 1.11 in the OR). This evidence suggests that endoscopy available around the clock during out-of-hours and during normal working hours is important for the quality of care for patients with UGIH; better randomized trials should be conducted to confirm it in future.

Some studies reported that patients admitted with UGIH on weekends tended to be sicker than those admitted on weekdays,2,7,21,23 whereas others suggested that the severity of illness was comparable irrespective of the time of admission.8,10,12,17,19 In the current meta-analysis, we assessed the proportion of patients who presented to the hospital with an active bleeding ulcer (Forrest Ia, Ib) during off-hours and regular hours; however, no significant difference appeared (median proportion: off-hours 31.37% vs regular hours 36.5%, p = 0.425). Subgroup analysis further suggested that in studies in which the mortality outcome was adjusted for baseline patient characteristics (e.g. presence with shock, melena or hematemesis, comorbidity (Charlson's) or Rockall score, or high-risk stigmata (active bleeding, visible vessels, clots)), the increase in mortality for off-hours admission remained significant. This finding was similar to what Ahmed et al. reported in 2015, which showed that although patients with UGIH appeared to have a higher Charlson's score at admission on weekends, 30-day mortality remained significantly higher after correction for the comorbidity.21 While other confounding factors derived from the difference in case mix cannot be excluded, these results may indicate that the increase in mortality during off-hours may be related to factors that arise after hospital admission.25

In the current study, subgroup analysis demonstrated that patients with nonvariceal bleeding had a significantly higher mortality when admitted during off-hours, while this effect did not exist for variceal bleeding, which is generally believed to be more lethal. The exact reason for this difference is unknown, but one study showed that the early start of standardized pre-endoscopic management such as correction of coagulopathy and intravenous vasopressor therapy, as well as emphatic sense of urgent endoscopic hemostasis, would lower the risk for patients with substantial variceal hemorrhage.15

It is a common belief that the increase in mortality would result in the extension of hospital stay; however, the current meta-analysis did not find an overall significant difference for LOS between patients admitted during off-hours and regular hours. This conflicting result may be due to heterogeneity; statistics confirmed that the region of studies served as the potential source of heterogeneity in the analysis of LOS (p < 0.001). In fact, subgroup analysis by restricting to the studies in North America and Europe showed that the increase in mortality for off-hours admission translated to longer LOS for patients with UGIH.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis has several limitations. Firstly, all data recruited in the current review were from retrospective or prospective observational studies. The results may be confounded by variations in patients' clinical characteristics, as well as management strategies on UGIH among different hospitals and countries worldwide. Secondly, there was a significant heterogeneity among the recruited studies. We found that the source of bleeding, region of studies and the outcome adjustment could be potential explanations. Other unexplained heterogeneity may be attributed to the different definitions of the “off-hours period,” mixes of patients, or the expertise of staff among institutions. Thirdly, the combined result of overall mortality for off-hours admission may be influenced by two dominating studies (Ahmed et al.21 and Shaheen et al.4). We performed sensitivity analysis by sequential exclusion of both studies, and found that the pooled result was not significantly influenced by individual research. So this concern is reduced.

In conclusion, the current systematic review and meta-analysis showed that patients with nonvariceal UGIH who were admitted during off-hours had significantly higher mortality and less timely endoscopy. However, this effect might be offset in hospitals with a formal out-of-hours endoscopic service. Our results implied that strategies should focus on improving clinical care for GI bleeding during out-of-hours visits. Further studies should be conducted to confirm the impact of early endoscopy on the prognosis for patients with UGIH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr Adrian J Stanley and Dr Asma Ahmed (GI Unit, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Castle Street, G4 0SF Glasgow, United Kingdom) for their kind support in providing additional information about their article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Gralnek IM, Barkun AN, Bardou M. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 928–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Groot NL, Bosman JH, Siersema PD, et al. Admission time is associated with outcome of upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Results of a multicentre prospective cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36: 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Button L, Roberts S, Evans P, et al. Hospitalized incidence and case fatality for upper gastrointestinal bleeding from 1999 to 2007: A record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33: 64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaheen AA, Kaplan GG, Myers RP. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from gastrointestinal hemorrhage caused by peptic ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tufegdzic M, Panic N, Boccia S, et al. The weekend effect in patients hospitalized for upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A single-center 10-year experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26: 715–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abougergi MS, Travis AC, Saltzman JR. Impact of day of admission on mortality and other outcomes in upper GI hemorrhage: A nationwide analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 80: 228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jairath V, Kahan B, Logan R, et al. Mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the United Kingdom: Does it display a “weekend effect”? Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1621–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsoi KK, Chiu PW, Chan FK, et al. The risk of peptic ulcer bleeding mortality in relation to hospital admission on holidays: A cohort study on 8,222 cases of peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Y, Li W, Herath C, et al. Off-hour admission and mortality risk for 28 specific diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 251 cohorts. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e003102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youn YH, Park YJ, Kim JH, et al. Weekend and nighttime effect on the prognosis of peptic ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 3578–3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byun SJ, Kim SU, Park JY, et al. Acute variceal hemorrhage in patients with liver cirrhosis: Weekend versus weekday admissions. Yonsei Med J 2012; 53: 318–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu TC, Chuah SK, Chang KC, et al. Outcome of holiday and nonholiday admission patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding: A real-world report from Southern Taiwan. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 906531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Qahatani HH, Hussain MI, Alam MK, et al. Impact of weekend admission on the outcome of patients with acute gastro-esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Kuwait Med J 2015; 47: 231–235. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas JM, Gundrum JD, Rathgaber SW. Comparison of time to endoscopy and outcome between weekend/weekday hospital admissions in patients with upper GI hemorrhage. WMJ 2012; 111: 161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myers RP, Kaplan GG, Shaheen AM. The effect of weekend versus weekday admission on outcomes of esophageal variceal hemorrhage. Can J Gastroenterol 2009; 23: 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weeda ER, Nicoll BS, Coleman CI, et al. Association between weekend admission and mortality for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: An observational study and meta-analysis. Intern Emerg Med 2017; 12: 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serrao S, Jackson C, Juma D, et al. In-hospital weekend outcomes in patients diagnosed with bleeding gastroduodenal angiodysplasia: A population-based study, 2000 to 2011. Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 84: 416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmulewitz L, Proudfoot A, Bell D. The impact of weekends on outcome for emergency patients. Clin Med (Lond) 2005; 5: 621–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parente F, Anderloni A, Bargiggia S, et al. Outcome of non-variceal acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in relation to the time of endoscopy and the experience of the endoscopist: A two-year survey. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 7122–7130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choudari CP, Palmer KR. Outcome of endoscopic injection therapy for bleeding peptic ulcer in relation to the timing of the procedure. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1993; 5: 951–954. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed A, Armstrong M, Robertson I, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Scotland 2000–2010: Improved outcomes but a significant weekend effect. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 10890–10897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammed N, Rehman A, Swinscoe MT, et al. Outcomes of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in relation to timing of endoscopy and the experience of endoscopist: A tertiary center experience. Endosc Int Open 2016; 4: E282–E286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorn SD, Shah ND, Berg BP, et al. Effect of weekend hospital admission on gastrointestinal hemorrhage outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55: 1658–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K. Outcomes of weekend admissions for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: A nationwide analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 296–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorita A, Ahmed A, Starr SR, et al. Off-hour presentation and outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014; 348: f7393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nanchal R, Kumar G, Taneja A, et al. Pulmonary embolism: The weekend effect. Chest 2012; 142: 690–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin HJ, Wang K, Perng CL, et al. Early or delayed endoscopy for patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: A prospective randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996; 22: 267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim L, Ho K, Chan Y, et al. Urgent endoscopy is associated with lower mortality in high-risk but not low-risk nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 2011; 43: 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.