Abstract

The anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy is a standard of care in the first-line treatment of RAS wild-type (wt) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) and has demonstrated efficacy in later lines. Progressive disease (PD) occurs when tumours develop resistance to a therapy, although controversy remains about whether PD on a combination of chemotherapy and targeted agents implies resistance to both components. Here, we propose that some patients may gain additional clinical benefit from the reuse of cetuximab after having PD on regimens including cetuximab in an earlier treatment line. We conducted a non-systematic literature search in PubMed and reviewed published and ongoing clinical trials, focusing on later-line cetuximab reuse in patients with mCRC. Evidence from multiple studies suggests that cetuximab can be an efficacious and tolerable treatment when continued or when fit patients with mCRC are retreated with it after a break from anti-EGFR therapy. Furthermore, on the basis of available preclinical and clinical evidence, we propose that longitudinal monitoring of RAS status may identify patients suitable for such a strategy. Patients who experience progression on cetuximab plus chemotherapy but have maintained RAS wt tumour status may benefit from continuation of cetuximab with a chemotherapy backbone switch because they have probably developed resistance to the chemotherapeutic agents rather than the biologic component of the regimen. Conversely, patients whose disease progresses on cetuximab-based therapy due to drug-selected clonal expansion of RAS-mutant tumour cells may regain sensitivity to cetuximab following a defined break from anti-EGFR therapy. Looking to the future, we propose that RAS status determination at disease progression by liquid, needle or excisional biopsy may identify patients eligible for cetuximab continuation and rechallenge. With this approach, treatment benefit can be extended, adding to established continuum-of-care strategies in patients with mCRC.

Keywords: metastatic colorectal cancer, cetuximab, ras, retreatment, continuum of care

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the fourth most prevalent cancer type in the world and causes nearly 700 000 deaths per year worldwide.1 Patients diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) have a limited number of systemic therapeutic options available as well as local therapies, such as resection, ablation or transhepatic irradiation via the injection of yttrium 90. Encouragingly, the median overall survival (OS) in recent phase III first-line trials in RAS wild-type (wt) mCRC now exceeds 30 months.2–5

The available biologic agents usually planned for first-line therapy include the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) cetuximab or panitumumab and the anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agent bevacizumab. All three agents, plus additional targeted drugs such as aflibercept (VEGF inhibitor), regorafenib (receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and ramucirumab (anti-VEGF receptor 2), have also shown efficacy in the second and later lines of therapy.6–12 Mounting evidence from randomised, phase III trials and meta-analyses suggests that many patients with RAS wt tumours may experience improved survival outcomes when chemotherapy is combined with cetuximab compared with combination with bevacizumab in the first-line setting.3 5 13–15 Retrospective analyses and meta-analyses have shown that the survival benefit is especially pronounced in patients with RAS wt, left-sided primary tumours.16–19 Although patients with right-sided tumours appear to derive less significant benefits from all available therapies for mCRC in terms of overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than do those with tumours originating in the left side of the colon,18–20 some patients may benefit from cetuximab-based therapy if the goal of treatment is response and subsequent cytoreduction.18 19 Indeed, cetuximab has been shown to yield a very good ORR, early tumour shrinkage (ETS) and depth of response in patients with RAS wt tumours. Such alternative metrics of response have been shown to be associated with improvements in survival5 compared with bevacizumab in the randomised, phase III, first-line FIRE-3 trial (5-FU, Folinic Acid and Irinotecan (FOLFIRI) Plus Cetuximab Versus FOLFIRI Plus Bevacizumab in First Line Treatment Colorectal Cancer), which evaluated patients with RAS wt mCRC.5 21

Currently, amplifications and mutations in several genes other than RAS, detected pretherapy, are also being investigated as potential predictive biomarkers of response to anti-EGFR therapy. The BRAF V600E variant22 23 appears to be a negative prognostic marker, but due to the relatively low number of colorectal cancers harbouring BRAF mutations (and as not all BRAF mutations confer resistance), controversy remains regarding the impact of this finding.24 Other markers of interest include alterations in the EGFR pathway, mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit α gene (PIK3CA) and amplification of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 gene, HER2 (mostly in patients with anti-EGFR-refractory, RAS wt disease).25–33 Furthermore, hypermethylation of tumour DNA appears to be potentially predictive of poorer clinical outcomes in patients receiving anti-EGFR therapy.34 35 The individual frequencies of all of these mutations and amplifications are low,25 27 33 36 37 and conflicting data exist regarding whether several of these genomic alterations are true biomarkers for cetuximab resistance. Additional biomarkers that are currently being explored as predictive of cetuximab response include VEGF2, MET (mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor mutations), fibroblast growth factor receptor mutations, platelet-derived growth factor, epiregulin, amphiregulin, mIR 31–3 p and hepatocyte growth factor.29 30 38–46 Presently, however, RAS mutations and tumour sidedness remain the only robust factors when selecting patients for anti-EGFR therapy in accordance with the drug labels for both cetuximab and panitumumab and the established international guidelines10 47 and are the most informative for treatment decisions in mCRC.

Colorectal tumours that are RAS wt at baseline can evolve resistance to anti-EGFR therapy via a RAS status ‘shift’ to mutated status to escape the drug’s effects.39 It is now known that this change occurs when the RAS wt tumour cell population is diminished during anti-EGFR therapy, while pre-existing or newly evolving RAS-mutant subclones can proliferate and become detectable by DNA testing.27 29 48 Other gene mutations, including in BRAF, may be subject to the same tumour heterogeneity principles and drug selection dynamics. Another key mechanism of acquired resistance that occurs in approximately 25% of patients treated with anti-EGFR therapy are mutations in the extracellular domain (ECD) of EGFR that prevent further binding of anti-EGFR mAbs to EGFR. Importantly, EGFR ECD alterations emerge as a means for cancer cells to circumvent EGFR blockade—acquired resistance—and do not apparently exist as a mechanism of primary resistance in anti-EGFR-naïve patients. Interestingly, the frequency and type of EGFR ECD mutation varies, depending on previous treatment with cetuximab or panitumumab, and each different EGFR ECD mutation may potentially confer resistance to cetuximab only, panitumumab only or both mAbs.28 49–51 Finally, these mutations frequently coexist in the same patient at the moment of disease progression, as multiple RAS, BRAF and EGFR clones are detectable in cell-free circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) by liquid biopsy.29 52

Extending the continuum of care through the delivery of as many lines of efficacious therapy as possible is desirable so that patients with progressive disease (PD) have multiple potentially beneficial treatment options to explore before transitioning into palliative care. For mCRC, however, patients with RAS wt tumours are generally assigned two lines of intensive therapy. They receive a first-line anti-EGFR mAb (cetuximab or panitumumab) or bevacizumab plus doublet/triplet chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan (FOLFIRI), 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI)). This is followed by second-line ‘switch’ of either the biologic, the chemotherapy backbone or both on PD. For patients who respond to a therapy and whose disease does not progress but require an interruption due to their preference or recovery from drug toxicity or surgery, a pause-and-resume (commonly referred to as stop-and-go or reintroduction/re-exposition) schedule of a biologic with or without chemotherapy can help them to complete the full planned treatment and maintenance period.53–55

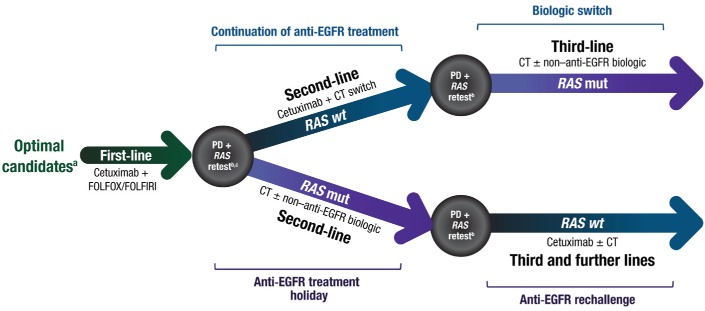

Multiple studies with dedicated second-line, third-line or mixed second-line and further-line patient populations have indicated improved survival and ORR with cetuximab monotherapy or cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy56–62 and with panitumumab monotherapy or panitumumab plus chemotherapy.57 63–67 Overall, all current guidelines conclude that patients with RAS wt mCRC who do not receive a biologic in the first line (but are fit enough to receive it in later lines) should be considered candidates for an anti-EGFR therapy in the next available line. Then, in the third line and beyond, patients are usually offered other targeted or chemotherapy-based interventions, often with limited expectations of clinical benefit. This is because, currently, it is widely accepted that after patients with left-sided, RAS wt mCRC have received an anti-EGFR antibody and bevacizumab sequentially (in either order) and experience progression, their disease is permanently resistant to both the biologic and cytotoxic agents that have been administered. However, this conclusion may not be accurate for all patients as some tumours may retain sensitivity to the targeted agent (although becoming resistant to the cytotoxic agents in the chemotherapy programme) or regain sensitivity after a ‘treatment break’ from those specific agents.68–73 Thus, many patients exhaust standard treatment options while maintaining a good performance status and are therefore not ready to transition to a solely palliative-care approach. Here, we review the evidence for continuation or reuse strategies beyond the first line with cetuximab, a well-established agent for RAS wt mCRC, as a method of expanding the therapeutic options available to patients and maximising the number of (potentially curative) therapeutic lines before the initiation of palliative care (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A proposed treatment model for the decision-making process when choosing between cetuximab continuation vs rechallenge. aTypically patients with left-sided, RAS wt mCRC or those with right-sided, RAS wt mCRC in need of rapid tumour shrinkage. bBy liquid biopsy. cOther evidence-based biomarkers can also be included in the panel of tests when feasible. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FOLFIRI, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan; FOLFOX, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin; mut, mutant; PD, progressive disease; wt, wild-type.

Notably, the bulk of available evidence for anti-EGFR retreatment stems from trials that use cetuximab rather than panitumumab. Furthermore, the two mAbs are known to behave somewhat differently in the context of treatment sequencing.74–81

Selecting cetuximab-eligible patients by liquid biopsy testing

Because the predominance of specific tumour cell subclones is dictated by selection pressures such as targeted therapy, retreatment strategies with cetuximab could be individualised with longitudinal tracking of detectable RAS mutations (and any future confirmed predictive biomarker of response) as a measure of potential sensitivity to cetuximab.27 29 30 39 51 Depending on the location of metastatic disease in some patients, traditional tumour needle or excisional biopsies may be invasive and risky. Thus, a less invasive method is desirable (eg, liver needle aspirates or plasma sampling). This ‘liquid’ biopsy can fulfil the retesting requirement by providing a non-invasive method for the detection and analysis of ctDNA. Of note, >75% of patients with advanced CRC have been shown to have detectable ctDNA (79.8% in the RASANC study (RAS Mutation Testing in the Circulating Blood of Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer)),82 83 and multiple useful platforms currently exist to allow the identification of tumour mutations via PCR of ctDNA: digital PCR84; digital next-generation sequencing85; BEAMing (beads, emulsion, amplification and magnetics)86; pyrophosphorolysis-activated polymerisation87; personalised profiling by deep sequencing88 and tagged-amplicon deep sequencing.89 Liquid biopsies have proven to be clinically robust. In a cohort of 98 patients with mCRC, Schmiegel et al90 used BEAMing to test for RAS tumour mutation status and found 91.8% concordance between ctDNA and tissue-based testing. Similarly, Vidal et al91 detected a 93% concordance rate in a cohort of 115 patients with mCRC. In the prospective, multicentre RASANC study (n=425), the concordance rate was 83.7% in the overall population and was even higher in patients with their primary tumour in place, liver metastasis and synchronous disease.83

Overall, RAS is the only widely recognised predictive molecular biomarker of cetuximab response and the only biomarker with extensive evidence of a high concordance between tissue-based and blood-based testing. However, we will refer to patients under consideration in this article more generally as ‘cetuximab-eligible patients’, for whom this definition is subject to change as additional research is published in the coming years. Furthermore, no subgroup analyses by tumour location are available for the studies on treatment beyond progression discussed here. However, we use the term ‘cetuximab-eligible’ to encompass optimal candidates for cetuximab-based therapy, including those with left-sided, RAS wt mCRC, and those with right-sided, RAS wt mCRC for whom cytoreduction is a key treatment goal, or who have previously responded to cetuximab-based therapy.

Continuation treatment strategy

Patients who received and progressed on cetuximab-containing regimens in the preceding line may retain cetuximab sensitivity,68–70 92 having instead become refractory to the chemotherapy backbone (table 1). In a study conducted by Feng et al,69 patients with RAS wt tumours whose disease progressed during first-line cetuximab plus chemotherapy were randomised to receive a different chemotherapy backbone with or without cetuximab as second-line treatment. The cetuximab-continuation group demonstrated better PFS, OS and disease control rates and a potentially better ORR than did the chemotherapy-only (no cetuximab continuation) group. Extended RAS analysis for the retrospective study revealed that baseline RAS wt status correlated with response to continuation of cetuximab; ETS during first-line cetuximab-based treatment also correlated with improved efficacy outcomes during second-line cetuximab continuation. Additionally, Ciardiello et al68 found evidence of a survival benefit from continued cetuximab plus FOLFOX in patients whose disease progressed during first-line cetuximab plus FOLFIRI and had KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA wt tumours. Both Feng et al and Ciardiello et al switched chemotherapy backbones when going from first-line to second-line treatment and used a chemotherapy switch alone as a comparator arm. Therefore, if sensitivity to cetuximab was preserved, switching to a non-cross-resistant chemotherapy backbone after PD could reinvigorate responsiveness. No new safety findings were identified from cetuximab continuation in any of these studies.68 69 72

Table 1.

Evidence for cetuximab continuation plus chemotherapy backbone switch in patients with KRAS wt (or retrospectively evaluated RAS wt) mCRC whose disease has progressed on cetuximab plus chemotherapy treatment

| Line of treatment | Study | Previous regimen | Arm A | Arm B | ||||

| PFS, mo | OS, mo | ORR, % | PFS, mo | OS, mo | ORR, % | |||

| Dedicated second line | Feng et al69 (2016; retrospective study) | Cetuximab+mFOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI | Cetuximab+CT switch (n=102) | CT switch (n=96) | ||||

| 6.3* | 17.3* | 18.6 | 4.5 | 14.0 | 9.4 | |||

| Ciardiello et al68 (2015; CAPRI-GOIM†) | Cetuximab+FOLFIRI | Cetuximab+FOLFOX (n=34) | CT switch (n=32) | |||||

| 6.9* | 23.7 | 29.4 | 5.3 | 19.8 | 9.4 | |||

| Vladimirova et al72 (2016) | Cetuximab+FOLFOX | Cetuximab+FOLFIRI (n=20) | ||||||

| 6.5‡ | – | 20.0 | ||||||

| Mixed third and further lines | Fora et al70 (2013) | Standard-dose cetuximab+irinotecan | High-dose cetuximab+irinotecan | |||||

| 2.8‡ | 6.6‡ | (DCR=45) | ||||||

All studies included a KRAS wt population, except where indicated.

*P<0.05.

†Retrospective extended RAS/BRAF/PIK3CA wt.

‡OS2 and PFS2 shown instead of all OS and PFS.

CT, chemotherapy; DCR, disease control rate; FOLFIRI, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan; FOLFOX, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; wt, wild-type.

By contrast, the majority of panitumumab retreatment trials have followed the stop-and-go (re-exposition) model rather than continuation (ie, patients did not experience progression on panitumumab immediately before retreatment).93 94 For example, a phase II Japanese study examining the administration of panitumumab plus chemotherapy following six cycles of first-line panitumumab plus FOLFOX is currently ongoing (SAPPHIRE (Safety and Efficacy Study of mFOLFOX6 + Panitumumab Combination Therapy and 5-FU/LV + Panitumumab Combination Therapy in Patients With Chemotherapy-naïve Unresectable Advanced Recurrent Colorectal Carcinoma); NCT02337946); therapy prolongation appears to be planned in the absence of PD, and the focus of the study is the feasibility of oxaliplatin treatment extension rather than panitumumab continuation.95

As has been demonstrated, deriving maximum benefit from cetuximab before introducing a biologic switch could extend the number of potentially efficacious lines of therapy for fit patients and thereby optimise the continuum of care.69 We advance the hypothesis that using ETS during first-line cetuximab and extended RAS analysis at PD can enable effective patient selection for this therapeutic strategy (figure 1).69 For patients whose tumours transition from cetuximab sensitive to insensitive (eg, by converting to RAS mutant), a treatment break followed by cetuximab rechallenge may allow another means of extending the continuum of care. Here, again, liquid biopsy for RAS status may prove highly informative.

Rechallenge treatment strategy

Evidence of rechallenge therapy in multiple tumour types has been published.96–98 Because no conclusive randomised trials have been completed to test whether longitudinal RAS status monitoring can identify patients who regain cetuximab sensitivity, we will outline the available preliminary preclinical (biological) and clinical support for this treatment approach.

Biological evidence

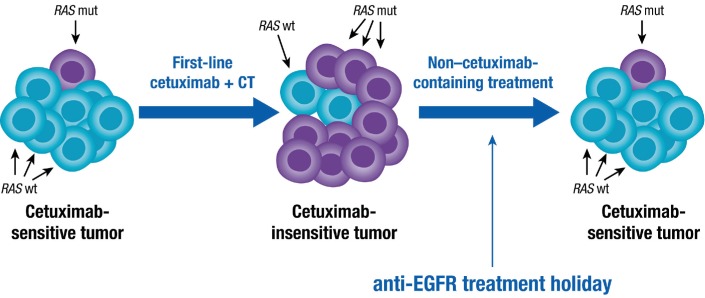

Tumour cells in a patient who is receiving treatment are constantly under selection pressures from the therapy being administered. Studies have suggested that mutations conferring resistance to therapy can arise during treatment. For example, when retested for (K)RAS status, >50% of patients with acquired resistance to first-line anti-EGFR therapy demonstrate a ‘switched’ status from (K)RAS wt to mutant,27 29–31 39 51 82 and the opposite observation (tumours switching from mutant KRAS to undetectable mutant status) has been made during bevacizumab treatment.99 Importantly, from studies monitoring plasma levels of RAS-mutant ctDNA, even short ‘holidays’ off anti-EGFR therapy may restore tumours to a cetuximab-sensitive state.39 68 100 Intratumour heterogeneity and drug-selected clonal evolution can account for these ‘switches’ (figure 2). The suggested mechanism for such a switch is the constant presence of a small number of RAS-mutant cell subclones persisting in the tumours, rather than de novo RAS mutations appearing in previously RAS wt tumour cells.73 Thus, a tumour can contain predominantly RAS wt clones, test as RAS wt and respond to cetuximab treatment until the RAS wt clones are depleted. In this environment, the RAS-mutant clones have the opportunity to continue proliferating and surviving and thus come to represent the dominant tumour subclonal population.51 100 Indeed, an in vitro study of two separate KRAS wt colorectal cancer cell populations showed that, under selection pressure from cetuximab treatment, the surviving population developed KRAS amplifications; when allowed to proliferate for 160 days without additional cetuximab treatment, the population of cells achieved significantly lower levels of KRAS amplification.39

Figure 2.

A model for the biological rationale for rechallenge therapy: clonal selection in heterogeneous baseline RASa wt tumours during anti-EGFR therapy. aAdditional or secondary acquired mechanisms of resistance can also be driven by mutations in the extracellular domain of the EGFR, and other potential biomarkers continue to be investigated. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; mut, mutant; wt, wild-type.

The principles of clonal selection likely also apply to other mechanisms of resistance to anti-EGFR therapy.29 Indeed, a number of genetic modifications beyond RAS have been related to acquired drug resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. Interestingly, most of these different genetic aberrations are related to or have influence on MEK-ERK pathway activity.101 The reversion of these additional resistance mechanisms during the anti-EGFR therapy break is controversial and not yet clearly demonstrated. Finally, it should be noted that even if arising on-treatment mutations have been identified, the exact threshold associated with resistance to anti-EGFR therapy has not been established, and some patients continue to experience disease control for several months after RAS-mutant clones emerge.51 102 Overall, there is a strong biological rationale for cetuximab rechallenge.

Clinical evidence

There is currently abundant clinical evidence for RAS status switch103 104 but little evidence analysing the direct relationship between a return to undetectable RAS-mutant status and a resensitisation to cetuximab.39 However, there exists clinical evidence for the feasibility of cetuximab rechallenge in patients with baseline (K)RAS wt mCRC whose disease progresses on first-line anti-EGFR therapy plus chemotherapy; such patients are usually rechallenged with cetuximab with or without chemotherapy in the later-line setting after ≥3 months of therapy that does not contain an anti-EGFR targeted agent. In a study by Santini et al73 (table 2), 39 patients whose disease had previously progressed on cetuximab plus irinotecan-based therapy were rechallenged with cetuximab plus irinotecan after a treatment break during which they received non-irinotecan-based chemotherapy alone. The median treatment break for these patients was 6 months, and patients had received a median of four lines of therapy prior to study enrolment. Nevertheless, median PFS was 6.6 months, and the ORR with cetuximab plus irinotecan rechallenge was 53.8% and included two complete responses. Stable disease was achieved by a further 35.9%, for a total disease control rate of 89.7%. Finally, in a recent prospective study by Gruppo Oncologico del Nord Ovest in Italy, the CRICKET study (Cetuximab Rechallenge in Irinotecan-pretreated mCRC, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF Wild-type Treated in 1st Line With Anti-EGFR Therapy), 27 patients with mCRC were to be treated with cetuximab plus FOLFIRI or FOLFOXIRI in the first line followed by bevacizumab plus oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in the second line and cetuximab plus irinotecan rechallenge in the third line. The third-line ORR was 23%, with 54% of patients experiencing disease control, and the study met its primary end point.105 Rechallenge treatment was well tolerated in all studies. The prospective biological determinations of ctDNA are ongoing.

Table 2.

Evidence for cetuximab rechallenge in patients with KRAS wt mCRC whose disease has previously progressed on cetuximab plus chemotherapy treatment and received who have received at least one line of additional, non–anti-EGFR therapy

| Study | Previous regimen |

| Liu et al71 (2015; retrospective study) | Summary:

|

| Santini et al73 (2012) | Summary:

|

| Rossini et al105 (2017; CRICKET) | Summary:

|

CR, complete response; CT, chemotherapy; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FOLFIRI, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan; IRI, irinotecan; mCRC, metastatic colorectal cancer; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; wt, wild-type.

Also noteworthy is a retrospective study by Liu et al71analysing patients with baseline KRAS wt status who received cetuximab (n=76) or cetuximab plus erlotinib (n=13) after a median of 4.57 months of treatment break from anti-EGFR therapy. Patients who had previously responded to anti-EGFR therapy achieved a median PFS of nearly 5 months.71 Rechallenge treatment was found to be well tolerated. Additionally, Liu et al71 suggested that the length of the anti-EGFR treatment interval may be related to the responsiveness of patients to rechallenge, on the basis of the observation that patients whose break from anti-EGFR therapy was longer than the median appeared more likely to respond. Overall, these studies suggest that good ORR and PFS can be achieved with cetuximab rechallenge in a patient population that has experienced progression on many prior lines of therapy, and these observations underscore the importance of optimising and extending the continuum of care.

One limitation of both the retrospective trial by Liu et al and prospective trial by Santini et al (except the CRICKET study) is that enrolment occurred prior to the standardisation of extended RAS analysis; therefore, data are not yet available for patients with RAS wt tumours. Furthermore, no retest was conducted for RAS status as liquid biopsy had not yet been validated. However, the fact that a patient population with previous progression on cetuximab-based therapy can achieve a median PFS of 5–6 months with rechallenge suggests that sensitivity to cetuximab, at least in some patients, can be meaningfully regained. However, certain selection criteria could be recommended here, such as establishing a minimum recommended treatment break length or selecting patients who had a durable response or disease stabilisation during the last cetuximab-based treatment.

Additional evidence for cetuximab rechallenge therapy can be found in case studies.103 106 107 Of note, Siravegna et al39 identified a patient with mCRC who initially achieved stable disease for 6 months with cetuximab plus irinotecan; on disease progression, the patient received XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) and experienced progression again after 3 months. The patient was then rechallenged with cetuximab plus irinotecan and achieved a partial response.

Notably, anti-EGFR rechallenge strategy data are available primarily for cetuximab but not for panitumumab. The limited data on panitumumab rechallenge come from two case reports by Siravegna et al,39 in which the patients achieved a partial response and stable disease when retreated with panitumumab following RAS mutational status switch and reversal. Additionally, Hata et al108 describe two patients with good outcomes when retreated with panitumumab after a line of non-anti-EGFR therapy, although neither patient had experienced PD during prior panitumumab-based therapy (in the earlier line, one stopped panitumumab treatment due to toxicity, and the other had completed the determined number of panitumumab cycles). Finally, some reports have described responses to panitumumab treatment after failure of cetuximab, primarily in heavily pretreated patients.109 110

Ongoing studies, including additional analyses of the CRICKET study (NCT02296203), a study in Japan (UMIN000016439), and a similar study in Israel (trial identification number not yet available), will help determine whether this treatment strategy is feasible and which patients are most suitable for this approach. Although no completed trial to date has tracked RAS mutational status longitudinally throughout treatment, progression and rechallenge, a highly relevant phase III trial (FIRE-4; NCT02934529) is currently being conducted. This study has a planned enrolment of 550 patients with RAS wt mCRC who will receive first-line cetuximab-based therapy and third-line cetuximab rechallenge. This trial specifically includes non-invasive (liquid biopsy) RAS status assessment on PD and will thus directly test our proposal that longitudinal RAS status monitoring can be a tool in selecting patients suitable for cetuximab rechallenge after a treatment break. As of this writing, the FIRE-4 study is actively recruiting patients and has an estimated completion date of March 2022.

Although the studies we have reviewed have reported good clinical efficacy with cetuximab continuation and rechallenge, and evidence of a possible connection to RAS status switch, the treatment strategies outlined in figure 1 are not considered routine practice at this time. As new evidence emerges and patient selection becomes more refined, these strategies are likely to become valuable for oncologists looking to extend the continuum of potentially curative therapy for patients with a good performance status. Finally, it is also possible that other mechanisms of acquired resistance to cetuximab (eg, EGFR,27 51 HER2/MET amplifications,104 KRAS/NRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA111 112) arise in the same way and coexist in the same tumour. Some may be subject to similar dynamics of clonal selection under pressure, and, therefore, return to predominantly wt status after the anti-EGFR treatment is halted (except for EGFR ECD mutations, which do not pre-exist in untreated tumours but emerge de novo under anti-EGFR treatment and persist in the tumour).51

Conclusion

Anti-EGFR mAb plus chemotherapy is a standard of care in the first-line setting for patients with RAS wt mCRC, with a particular benefit for patients with left-sided tumours.10 11 Importantly, cetuximab can also be a significant component in second-line and later-line treatments, thereby affording additional treatment opportunities to suitable patients and optimising and extending the continuum of care. In cetuximab-naïve patients, later-line treatment with cetuximab plus chemotherapy generally results in efficacy benefits over chemotherapy alone.56 59 Use of cetuximab monotherapy or cetuximab plus chemotherapy in second-line and later-line mCRC does not yield any new safety signals, thereby further supporting its utility.56 57 59 113 114

Notably, patients do not have to be cetuximab naïve to extract benefits from second-line and later-line use of cetuximab.68–70 72 Treatment with cetuximab beyond progression in conjunction with a different chemotherapy backbone results in efficacy benefits, although this approach still needs to be confirmed in a large-scale clinical study. Evaluation of tumour RAS status on progression on first-line cetuximab plus chemotherapy may be informative in identifying candidates for continuation of cetuximab after the RAS threshold relevant for clinical resistance has been determined. Additionally, patients whose tumours ‘switched’ to RAS-mutant status following previous cetuximab-based therapy can regain cetuximab sensitivity and be rechallenged with cetuximab after a ‘holiday’ of several months, with renewed efficacy benefits.71 73 Liquid biopsy-based RAS testing will be needed to select for patients who can receive continuation cetuximab in the second line versus a treatment break (from anti-EGFR therapy) followed by rechallenge in third or further lines. We anticipate the results of trials such as FIRE-4, which may solidify the concept of cetuximab rechallenge as a routine therapeutic strategy to optimise and extend the continuum of care in patients with mCRC. To this end, further research into additional biomarkers of response to anti-EGFR agents will ensure definition of the optimal patient populations for these strategies, thereby maximising the continuum of care.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by ClinicalThinking, Hamilton, New Jersey, USA.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed equally in the conception, structuring, writing and development of this manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

Competing interests: RMG has declared no conflicts of interest. DS discloses advisory board membership for and honoraria for talks from Amgen, Janssen, Merck KGaA, Sanofi, Roche and Servier. PR and FA are employees of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. ZAW discloses consultation for and honoraria from Lilly, Genentech and Novartis. JT discloses honoraria from Merck, Amgen, Roche, Celgene, Baxalta, Lilly, Servier and Sanofi. CM discloses advisory board membership for and honoraria for talks from Amgen, Merck KGaA, Roche, Sanofi, Servier and Symphogen. SaSi discloses advisory board membership for Amgen, Roche, Novartis, Ignyta, Bayer, Sanofi and Eli Lilly. SeSt discloses advisory role and honoraria for talks from Amgen, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Merck KGaA, Roche, Sanofi and Takeda.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. GLOBOCAN. Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. 2012.

- 2. Van Cutsem E, Lenz H-J, Köhne C-H, et al. . Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan plus cetuximab treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:692–700. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lenz H, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti F, et al. . CALGB/SWOG 80405: phase III trial of FOLFIRI or mFOLFOX6 with bevacizumab or cetuximab for patients with expanded RAS analyses in untreated metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum. ESMO 2014. Abstract 501O. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Falcone A, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. . FOLFOXIRI/bevacizumab (bev) versus FOLFIRI/bev as first-line treatment in unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients (pts): results of the phase III TRIBE trial by GONO group. J Clin Oncol 2013;31 Abstract 3505. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stintzing S, Modest DP, Rossius L, et al. . FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a post-hoc analysis of tumour dynamics in the final RAS wild-type subgroup of this randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1426–34. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30269-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bennouna J, Phelip J-M, André T, et al. . Observational cohort of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer initiating chemotherapy in combination with bevacizumab (CONCERT). Clin Colorectal Cancer 2017;16:129–40. 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hasegawa H, Taniguchi H, Mitani S, et al. . Efficacy of second-line bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer following first-line treatment with an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody. Oncology 2017;92:205–12. 10.1159/000453336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuramochi H, Ando M, Itabashi M, et al. . Phase II study of bevacizumab and irinotecan as second-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with fluoropyrimidines, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2017;79:579–85. 10.1007/s00280-017-3255-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tabernero J, Van Cutsem E, Lakomý R, et al. . Aflibercept versus placebo in combination with fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan in the treatment of previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: prespecified subgroup analyses from the VELOUR trial. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:320–31. 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. . ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016;27:1386–422. 10.1093/annonc/mdw235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Cohn AL, et al. . Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second-line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:499–508. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70127-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y, Liu S, Liu S, et al. . Regorafenib treatment for management of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials. Am J Ther 2018;25:e276–8. 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heinemann V, Rivera F, O’Neil BH, et al. . A study-level meta-analysis of efficacy data from head-to-head first-line trials of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors versus bevacizumab in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2016;67:11–20. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khattak MA, Martin H, Davidson A, et al. . Role of first-line anti–epidermal growth factor receptor therapy compared with anti–vascular endothelial growth factor therapy in advanced colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2015;14:81–90. 10.1016/j.clcc.2014.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumachev A, Yan M, Berry S, et al. . A systematic review and network meta-analysis of biologic agents in the first line setting for advanced colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140187 10.1371/journal.pone.0140187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, et al. . The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 2017;70:87–98. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, et al. . Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1713–29. 10.1093/annonc/mdx175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, et al. . Prognostic and predictive relevance of primary tumor location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: retrospective analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 Trials. JAMA Oncol 2016. (Epub ahead of print 10 Oct 2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Venook AP, Neidzwiecki D, Innocenti F, et al. . Impact of primary (1°) tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2016;34:Abstract 3504. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sagawa T, Hamaguchi K, Sakurada A, et al. . Primary tumor location as a prognostic and predictive factor in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) treated with chemotherapy plus cetuximab: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:711 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.4_suppl.711 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Modest DP, Stintzing S, Fischer von Weikersthal L, et al. . Relation of early tumor shrinkage (ETS) observed in first-line treatment to efficacy parameters of subsequent treatment in FIRE-3 (AIOKRK0306). Int J Cancer 2017;140:1918–25. 10.1002/ijc.30592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pietrantonio F, Petrelli F, Coinu A, et al. . Predictive role of BRAF mutations in patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving cetuximab and panitumumab: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:587–94. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.01.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rowland A, Dias MM, Wiese MD, et al. . Meta-analysis of BRAF mutation as a predictive biomarker of benefit from anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy for RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2015;112:1888–94. 10.1038/bjc.2015.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Summers MG, Smith CG, Maughan TS, et al. . BRAF and NRAS locus-specific variants have different outcomes on survival to colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2742–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Foltran L, Maglio GD, Pella N, et al. . Prognostic role of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA mutations in advanced colorectal cancer. Future Oncol 2015;11:629–40. 10.2217/fon.14.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Misale S, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore-Bianchi A, et al. . Resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer: from heterogeneity to convergent evolution. Cancer Discov 2014;4:1269–80. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morelli MP, Overman MJ, Dasari A, et al. . Characterizing the patterns of clonal selection in circulating tumor DNA from patients with colorectal cancer refractory to anti-EGFR treatment. Ann Oncol 2015;26:731–6. 10.1093/annonc/mdv005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Montagut C, Dalmases A, Bellosillo B, et al. . Identification of a mutation in the extracellular domain of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor conferring cetuximab resistance in colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2012;18:221–3. 10.1038/nm.2609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S, Tonini G, et al. . Overcoming dynamic molecular heterogeneity in metastatic colorectal cancer: multikinase inhibition with regorafenib and the case of rechallenge with anti-EGFR. Cancer Treat Rev 2016;51:54–62. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S. Plasticity of resistance and sensitivity to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in metastatic colorectal cancer. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2017. (Epub ahead of print 6 Apr 2017). 10.1007/164_2017_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, et al. . Biomarkers predicting clinical outcome of epidermal growth factor receptor–targeted therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:1308–24. 10.1093/jnci/djp280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sartore-Bianchi A, Trusolino L, Martino C, et al. . Dual-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in treatment-refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type, HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): a proof-of-concept, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:738–46. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00150-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jeong JH, Kim J, Hong YS, et al. . HER2 Amplification and cetuximab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer harboring wild-type RAS and BRAF. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2017;16:e147–52. 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ouchi K, Takahashi S, Yamada Y, et al. . DNA methylation status as a biomarker of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci 2015;106:1722–9. 10.1111/cas.12827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scartozzi M, Bearzi I, Mandolesi A, et al. . Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene promoter methylation and cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2011;104:1786–90. 10.1038/bjc.2011.161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, et al. . Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:753–62. 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70130-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tabernero J, Lenz H-J, Siena S, et al. . Analysis of circulating DNA and protein biomarkers to predict the clinical activity of regorafenib and assess prognosis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective, exploratory analysis of the CORRECT trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:937–48. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00138-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vallböhmer D, Zhang W, Gordon M, et al. . Molecular determinants of cetuximab efficacy. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3536–44. 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Siravegna G, Mussolin B, Buscarino M, et al. . Clonal evolution and resistance to EGFR blockade in the blood of colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med 2015;21:795–801. 10.1038/nm.3870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liska D, Chen C-T, Bachleitner-Hofmann T, et al. . HGF rescues colorectal cancer cells from EGFR Inhibition via MET activation. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:472–82. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pugh S, Thiébaut R, Bridgewater J, et al. . Association between miR-31-3p expression and cetuximab efficacy in patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: a post-hoc analysis of the New EPOC trial. Oncotarget 2017;8:93856–66. 10.18632/oncotarget.21291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sunakawa Y, Yang D, Moran M, et al. . Combined assessment of EGFR-related molecules to predict outcome of 1st-line cetuximab-containing chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2016;17:751–9. 10.1080/15384047.2016.1178426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saridaki Z, Tzardi M, Papadaki C, et al. . Impact of KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA mutations, PTEN, AREG, EREG expression and skin rash in ≥2nd line cetuximab-based therapy of colorectal cancer patients. PLoS One 2011;6:e15980 10.1371/journal.pone.0015980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Igarashi H, Kurihara H, Mitsuhashi K, et al. . Association of microRNA-31-5p with clinical efficacy of anti-EGFR therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:2640–8. 10.1245/s10434-014-4264-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chung S, Dwabe S, Elshimali Y, et al. . Identification of novel biomarkers for metastatic colorectal cancer using angiogenesis-antibody array and intracellular signaling array. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134948 10.1371/journal.pone.0134948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mizukami T, Togashi Y, Naruki S, et al. . Significance of FGF9 gene in resistance to anti-EGFR therapies targeting colorectal cancer: A subset of colorectal cancer patients with FGF9 upregulation may be resistant to anti-EGFR therapies. Mol Carcinog 2017;56:106–17. 10.1002/mc.22476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Colon cancer: NCCN Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. 2016. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx.

- 48. Lunke S, Lee B, Kranz S, et al. . Intratumorous heterogeneity for RAS mutations in a treatment-naïve colorectal tumour. J Clin Pathol 2017;70:720–3. 10.1136/jclinpath-2017-204327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sanchez-Martin FJ, Bellosillo B, Gelabert-Baldrich M, et al. . The first-in-class anti-EGFR antibody mixture sym004 overcomes cetuximab resistance mediated by EGFR extracellular domain mutations in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:3260–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arena S, Bellosillo B, Siravegna G, et al. . Emergence of multiple EGFR Extracellular mutations during cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2157–66. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Van Emburgh BO, Arena S, Siravegna G, et al. . Acquired RAS or EGFR mutations and duration of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 2016;7:13665 10.1038/ncomms13665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Strickler JH, Loree JM, Ahronian LG, et al. . Genomic landscape of cell-free DNA in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chang PH, Huang JS. Successful rechallenge of cetuximab following severe infusion-related reactions: a case report. Chin J Cancer Res 2014;26:E10–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. George TJ, Laplant KD, Walden EO, et al. . Managing cetuximab hypersensitivity-infusion reactions: incidence, risk factors, prevention, and retreatment. J Support Oncol 2010;8:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nielsen DL, Pfeiffer P, Jensen BV. Re-treatment with cetuximab in patients with severe hypersensitivity reactions to cetuximab. Two case reports. Acta Oncol 2006;45:1137–8. 10.1080/02841860600871764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hong YS, Kim HJ, Park SJ, et al. . Second-line cetuximab/irinotecan versus oxaliplatin/fluoropyrimidines for metastatic colorectal cancer with wild-type KRAS. Cancer Sci 2013;104:473–80. 10.1111/cas.12098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Price TJ, Peeters M, Kim TW, et al. . Panitumumab versus cetuximab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer (ASPECCT): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, non-inferiority phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:569–79. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pantelic A, Markovic M, Pavlovic M, et al. . Cetuximab in third-line therapy of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a single institution experience. J BUON 2016;21:70–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gil Delgado M, Spano J-P, Khayat D. Cetuximab plus irinotecan in refractory colorectal cancer patients. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2007;7:407–13. 10.1586/14737140.7.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lim R, Sun Y, Im SA, et al. . Cetuximab plus irinotecan in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer patients: the ELSIE study. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:1879–88. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i14.1879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Buzaid AC, de Cerqueira Mathias C, Perazzo F, et al. . Cetuximab plus irinotecan in pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer progressing on irinotecan: the LABEL study. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2010;9:282–9. 10.3816/CCC.2010.n.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wilke H, Glynne-Jones R, Thaler J, et al. . Cetuximab plus irinotecan in heavily pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer progressing on irinotecan: MABEL Study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5335–43. 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shitara K, Yonesaka K, Denda T, et al. . Randomized study of FOLFIRI plus either panitumumab or bevacizumab for wild-type KRAS colorectal cancer-WJOG 6210G. Cancer Sci 2016;107:1843–50. 10.1111/cas.13098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Peeters M, Oliner KS, Price TJ, et al. . Analysis of KRAS/NRAS mutations in a phase III study of panitumumab with FOLFIRI compared with FOLFIRI alone as second-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:5469–79. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, et al. . Final results from a randomized phase 3 study of FOLFIRI ± panitumumab for second-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2014;25:107–16. 10.1093/annonc/mdt523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, et al. . Randomized phase III study of panitumumab with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) compared with FOLFIRI alone as second-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4706–13. 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.6055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gasparini G, Buttitta F, D’Andrea MR, et al. . Optimizing single agent panitumumab therapy in pre-treated advanced colorectal cancer. Neoplasia 2014;16:751–6. 10.1016/j.neo.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ciardiello F, Normanno N, Martinelli E, et al. . Cetuximab beyond progression in RAS wild type (WT) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): the CAPRI-GOIM randomized phase II study of FOLFOX versus FOLFOX plus cetuximab. Ann Oncol 2015;26:iv120–1. 10.1093/annonc/mdv262.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Feng Q, Wei Y, Ren L, et al. . Efficacy of continued cetuximab for unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer after disease progression during first-line cetuximab-based chemotherapy: a retrospective cohort study. Oncotarget 2016;7:11380–96. 10.18632/oncotarget.7193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fora AA, McMahon JA, Wilding G, et al. . A phase II study of high-dose cetuximab plus irinotecan in colorectal cancer patients with KRAS wild-type tumors who progressed after standard dose of cetuximab plus irinotecan. Oncology 2013;84:210–3. 10.1159/000346328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liu X, George GC, Tsimberidou AM, et al. . Retreatment with anti-EGFR based therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer: impact of intervening time interval and prior anti-EGFR response. BMC Cancer 2015;15:713 10.1186/s12885-015-1701-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vladimirova LY, Abramova NA, Kit OI. Treatment for RAS wild-type (wt) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): continuation of anti-EGFR therapy while switching chemotherapy regimen. ASCO 2016. Abstract 744. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Santini D, Vincenzi B, Addeo R, et al. . Cetuximab rechallenge in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: how to come away from acquired resistance? Ann Oncol 2012;23:2313–8. 10.1093/annonc/mdr623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Modest D, Stintzing S, Fischer von Weikersthal L, et al. . 2nd-line therapies after 1st-line therapy with FOLFIRI in combination with cetuximab or bevacizumab in patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) - analysis of the AIO KRK 0306 (FIRE 3) trial. ESMO GI 2014. Abstract 0-0018. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lam KO, Lee VH, Liu RK, et al. . Bevacizumab-containing regimens after cetuximab failure in Kras wild-type metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2013;5:637–40. 10.3892/ol.2012.1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Norguet E, Dahan L, Gaudart J, et al. . Cetuximab after bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: Is it the best sequence? Digestive and Liver Disease 2011;43:917–9. 10.1016/j.dld.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bianco R, Rosa R, Damiano V, et al. . Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 contributes to resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor drugs in human cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 2008;14:5069–80. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cascinu S, Rosati G, Nasti G, et al. . Treatment sequence with either irinotecan/cetuximab followed by FOLFOX-4 or the reverse strategy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients progressing after first-line FOLFIRI/bevacizumab: an Italian Group for the Study of Gastrointestinal Cancer phase III, randomised trial comparing two sequences of therapy in colorectal metastatic patients. Eur J Cancer 2017;83:106–15. 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bennouna J, Hiret S, Borg C, et al. . Bevacizumab (Bev) or cetuximab (Cet) plus chemotherapy after progression with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy in patients with wild-type (WT) KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): final analysis of a French randomized, multicenter, phase II study (PRODIGE 18). Ann Oncol 2017;28:v158–208. 10.1093/annonc/mdx393.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rosati G, Nasti G, Lonardi S, et al. . A phase III multicenter trial comparing two different sequences of second/third line therapy (irinotecan/cetuximab followed by FOLFOX-4 vs. FOLFOX-4 followed by irinotecan/cetuximab in K-RAS wt metastatic colorectal cancer (mCC) patients refractory to FOLFIRI/bevacizumab. Ann Oncol 2015;26:vi2 10.1093/annonc/mdv335.03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hecht JR, Cohn A, Dakhil S, et al. . SPIRITT: a randomized, multicenter, phase II study of panitumumab with FOLFIRI and bevacizumab with FOLFIRI as second-line treatment in patients with unresectable wild type KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2015;14:72–80. 10.1016/j.clcc.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. . Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:224ra24 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bachet JB, Bouche O, Taieb J, et al. . RAS mutations concordance in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and tissue in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): RASANC, an AGEO prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2017;35 Abstract 11509. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Digital PCR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:9236–41. 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lanman RB, Mortimer SA, Zill OA, et al. . Analytical and clinical validation of a digital sequencing panel for quantitative, highly accurate evaluation of cell-free circulating tumor DNA. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140712 10.1371/journal.pone.0140712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Dressman D, Yan H, Traverso G, et al. . Transforming single DNA molecules into fluorescent magnetic particles for detection and enumeration of genetic variations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:8817–22. 10.1073/pnas.1133470100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Liu Q, Sommer SS. Pyrophosphorolysis-activated polymerization (PAP): application to allele-specific amplification. BioTechniques 2000;29:1072–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J, et al. . An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med 2014;20:548–54. 10.1038/nm.3519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Forshew T, Murtaza M, Parkinson C, et al. . Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:136ra68 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Schmiegel W, Scott RJ, Dooley S, et al. . Blood-based detection of RAS mutations to guide anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer patients: concordance of results from circulating tumor DNA and tissue-based RAS testing. Mol Oncol 2017;11:208–19. 10.1002/1878-0261.12023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Vidal J, Muinelo L, Dalmases A, et al. . Plasma ctDNA RAS mutation analysis for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1325–32. 10.1093/annonc/mdx125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Vladimirova LY, Agieva AA, Engibaryan MA. Anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer. Vopr Onkol 2015;61:580–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Metges J, Raoul J, Achour N, et al. . PANERB study: panitumumab after cetuximab-based regimen failure. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:Abstract e14000 10.1200/jco.2010.28.15_suppl.e14000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pietrantonio F, Perrone F, Biondani P, et al. . Single agent panitumumab in KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer patients following cetuximab-based regimens: clinical outcome and biomarkers of efficacy. Cancer Biol Ther 2013;14:1098–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Nagata N, Mishima H, Kurosawa S, et al. . mFOLFOX6 plus panitumumab versus 5-FU/LV plus panitumumab after six cycles of frontline mFOLFOX6 plus panitumumab: a randomized phase II study of patients with unresectable or advanced/recurrent, RAS wild-type colorectal carcinoma (SAPPHIRE) — study design and rationale. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2017;16:154–7. 10.1016/j.clcc.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Araki K, Fukada I, Horii R, et al. . Trastuzumab rechallenge after lapatinib- and trastuzumab-resistant disease progression in HER2-positive breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2015;15:432–9. 10.1016/j.clbc.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Barbieri E, Rubino D, Hakim R, et al. . Eribulin long-term response and rechallenge: report of two clinical cases. Future Oncol 2017;13:35–43. 10.2217/fon-2016-0520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Cappuzzo F, Morabito A, Normanno N, et al. . Efficacy and safety of rechallenge treatment with gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2016;99:31–7. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Gazzaniga P, Raimondi C, Nicolazzo C, et al. . ctDNA might expand therapeutic options for second line treatment of KRAS mutant mCRC. 2017;28:v573–94. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Tonini G, Imperatori M, Vincenzi B, et al. . Rechallenge therapy and treatment holiday: different strategies in management of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2013;32:92 10.1186/1756-9966-32-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Sforza V, Martinelli E, Ciardiello F, et al. . Mechanisms of resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:6345–61. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i28.6345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Misale S, Yaeger R, Hobor S, et al. . Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature 2012;486:532–6. 10.1038/nature11156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Bouchahda M, Karaboué A, Saffroy R, et al. . Acquired KRAS mutations during progression of colorectal cancer metastases: possible implications for therapy and prognosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010;66:605–9. 10.1007/s00280-010-1298-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Pietrantonio F, Vernieri C, Siravegna G, et al. . Heterogeneity of acquired resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2414–22. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Rossini D, Santini D, Cremolini C, et al. . Rechallenge with cetuximab + irinotecan in 3rd-line in RAS and BRAF wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients with acquired resistance to 1st-line cetuximab+irinotecan: the phase II CRICKET study by GONO. Ann Oncol 2017;28:iii1–12. 10.1093/annonc/mdx263.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Hata A, Katakami N, Kitajima N. Successful cetuximab therapy after failure of panitumumab rechallenge in a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer: restoration of drug sensitivity after anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody-free interval. J Gastrointest Cancer 2014;45:506–7. 10.1007/s12029-014-9624-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ma J, Yang QL, Ling Y. Rechallenge and maintenance therapy using cetuximab and chemotherapy administered to a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2017;17:132 10.1186/s12885-017-3133-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hata A, Katakami N, Fujita S, et al. . Panitumumab rechallenge in chemorefractory patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer 2013;44:456–9. 10.1007/s12029-012-9453-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wadlow RC, Hezel AF, Abrams TA, et al. . Panitumumab in patients with KRAS wild-type colorectal cancer after progression on cetuximab. Oncologist 2012;17:14–34. 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kajitani T, Makiyama A, Arita S, et al. . Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody readministration in chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 2017;37:6459–68. 10.21873/anticanres.12101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Xu JM, Wang Y, Wang YL, et al. . PIK3CA mutations contribute to acquired cetuximab resistance in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:4602–16. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Toledo RA, Cubillo A, Vega E, et al. . Clinical validation of prospective liquid biopsy monitoring in patients with wild-type RAS metastatic colorectal cancer treated with FOLFIRI-cetuximab. Oncotarget 2017;8:35289–300. 10.18632/oncotarget.13311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Sobrero AF, Maurel J, Fehrenbacher L, et al. . EPIC: phase III trial of cetuximab plus irinotecan after fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin failure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2311–9. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Harbison CT, Horak CE, Ledeine JM, et al. . Validation of companion diagnostic for detection of mutations in codons 12 and 13 of the KRAS gene in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of the NCIC CTG CO.17 trial. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013;137:820–7. 10.5858/arpa.2012-0367-OA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]