Abstract

A 26-year-old woman with a history of idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura and a 1-year history of blood-streaked sputum presented after a severe episode of haemoptysis with dyspnoea. Chest imaging revealed diffuse ground glass and bronchovascular nodules. Bronchoscopy revealed bilateral diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH). Sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage studies were negative for infectious aetiologies. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed Libman-Sacks endocarditis with severe mitral regurgitation and physical examination revealed retinal artery occlusion and Osler’s nodes. The patient had an increased anticardiolipin Immunoglobulin IgG and anti-B2 glycoprotein IgG, suggesting antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS). The patient was then started on high-dose methylprednisolone and had an improvement in her dyspnoea and haemoptysis. She was also started on anticoagulation as treatment for Libman-Sacks endocarditis. APLS should be considered as a possible underlying aetiology for unusual presentations of DAH with concurrent Libman-Sacks endocarditis in non-intravenous drug users with existing autoimmune disorders.

Keywords: valvar diseases, haematology (incl blood transfusion), malignant and benign haematology, rheumatology, respiratory medicine

Background

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS) is an autoimmune condition which commonly presents as arterial and venous thrombosis and pregnancy morbidity defined by multiple spontaneous abortions. Contrary to this classic presentation, our patient presented with diffuse alveolar haemorrhage (DAH) and physical examination findings consistent with sterile endocarditis. This unusual constellation of symptoms in a non-intravenous drug user should be considered as a rare initial presentation for APLS.

Case presentation

A 26-year-old woman with a past medical history of idiopathic thrombocytopaenia purpura (ITP) and a 1-year history of blood streaked sputum presented after a severe episode of haemoptysis. Through the course of the prior year, she presented multiple times to her primary care physician and the emergency department for episodes of haemoptysis. Multiple workups for an underlying infectious cause were negative and her symptoms were refractory to antibiotic treatment for suspected community acquired pneumonia. On presentation, she also noted worsening central and peripheral vision in her left eye. She described her symptoms as seeing ‘a hazy spot wherever I look’. She denied recent travel, sick contacts, intravenous drug use, fevers, chills, chest pain or leg swelling.

Physical examination revealed a woman in no acute distress. Her vital signs were: temperature 37°C, heart rate 107 beats/min, blood pressure 124/94 mm Hg, respiratory rate 30 breaths/min, oxygen saturation 81% on 100% fraction of inspired oxygen through high flow nasal cannula. Given her decreased oxygen saturation, she was placed on bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) which increased her oxygen saturation to 100%. Her pulmonary examination was significant for decreased air movement bilaterally with rales and reduced breath sounds at both lung bases, symmetric chest expansion without egophony or fremitus. Cardiac examination showed normal rate, regular rhythm, normal S1 and S2, no S3 or S4, no murmurs, rubs or gallops and no pitting oedema. Skin examination showed tender, purple macules on her digits (figure 1). Visual field testing showed deficiency in the nasal visual field of her left eye. Dilated fundoscopic examination revealed a branch retinal artery occlusion.

Figure 1.

Left thumb demonstrating tender lesions underneath first digit (arrows).

Investigations

Laboratory results were remarkable for a white blood cell count of 14 500/mm3 (reference range=4.0–10.0 thousand/mm3), haemoglobin 8.2 g/dL (reference range=12.0–16.0 g/dL) and platelet count 53 000/mm3 (reference range=150–450 thousand/mm3). Given her increased need for oxygenation, an arterial blood gas was obtained and revealed pH 7.46 (reference range=7.35–7.45), PCO2 38.8 (reference range=35–45), PO2 53 mm Hg (reference range=90–105 mm Hg). A CT of the chest revealed diffuse ground glass and bronchovascular nodules.

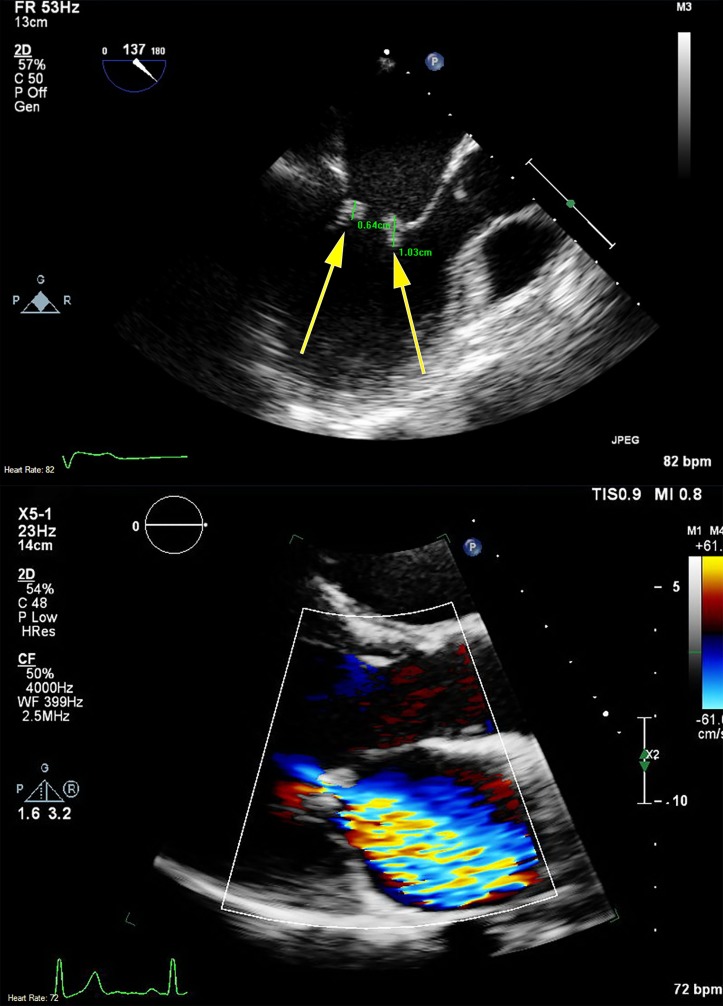

A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a severely dilated left atrium and mitral valve mass with associated severe mitral regurgitation. Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was obtained to investigate the presence of mitral valve insufficiency and its potential contribution to pulmonary congestion. The TEE revealed echodensities of anterior and posterior mitral valve leaflets on both the atrial and ventricular sides of the valve (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Echocardiogram images demonstrating 0.64 cm and 1.03 cm vegetations on both atrial and ventricular sides of the mitral valve (arrows) via transesophageal echocardiography (top) and severe mitral regurgitation by colour Doppler via transthoracic echocardiography (bottom).

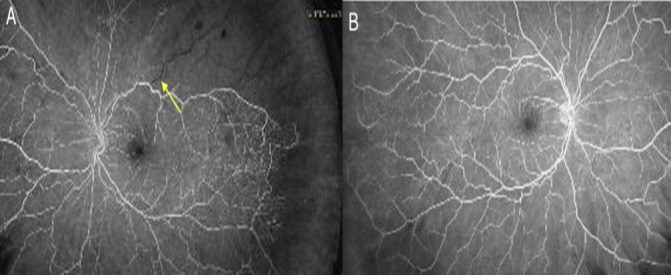

Fluorescein angiography examination revealed non-perfusion in wedge distribution in superior macular, superotemporal and superior periphery consistent with branch retinal artery occlusion of the left eye (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fundoscopic angiogram of left (A) and right eye (B) demonstrating decreased perfusion in left branch retinal artery (arrow) compared with adequate perfusion of retinal arteries in the right eye (B).

An infectious workup including a viral PCR panel, blood cultures and sputum cultures were negative. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed. Findings were consistent with DAH, serosanguinous fluid with an 82% polymorphonuclear leucocyte predominance, 12% monocytes and negative bronchoscopic sputum cultures.

Autoimmune workup included antinuclear antibody titer negative, anti-double stranded antibody negative, C3 complement 103 mg/dL (reference range 90–180 mg/dL), C4 complement 13 mg/dL (reference range 15–46 mg/dL). C-ANCA negative, P-ANCA negative, antiscleroderma 0 AU/mL (reference range 0–40 AU/mL), cryoglobulin negative, SM-RNP Ab <20 Units (reference range<20 Units), ADAMTS13 activity 84% (reference range>60%), anti-Smith IgG 0 AU/mL (reference range 0–40 AU/mL). However, anticardiolipin IgG 52.3 GPL u/mL (reference range≤20.0 GPL U/mL) and anti-B2 Glycoprotein IgG 24.2 SGU U/mL (reference range≤20.0 SGU U/mL) were positive.

Differential diagnosis

This patient presented with DAH and Libman-Sacks endocarditis. Individually, our DAH differential included:

Infection

Autoimmune

Flash pulmonary oedema

Vasculitis

Thrombocytopenia

Our endocarditis differential included:

Infection

Autoimmune

Intravenous drug use

Flash pulmonary oedema, vasculitis and intravenous drug use were ruled out. Infection and autoimmune conditions were included on our differential for both conditions. An extensive infectious workup was negative and the patient did not improve with antibiotic treatment. Osler’s nodes and branch retinal artery occlusion, combined with an autoimmune panel which showed elevated levels of anticardiolipin IgG and anti-B2 glycoprotein IgG suggested the diagnosis of APLS.

Treatment

Initial empiric therapy was initiated with Vancomycin, Aztreonam and Azithromycin. After her course of antibiotics with no improvement in her symptoms and oxygen saturation, she subsequently began high-dose methylprednisolone which led to significant clinical improvement. After 3 days of steroid therapy, she was taken off BiPAP and transitioned to high flow nasal cannula. Atovaquone was started for pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis in anticipation of a prolonged steroid course for treatment of ITP. Furosemide was added to her medication regimen and she was weaned to 1 L high flow nasal cannula by day 19. For her newly found Libman-Sacks endocarditis and severe mitral regurgitation, medical management included continued diuretic therapy and afterload reduction with lisinopril and carvedilol to maintain a blood pressure of less than 120/80. In addition, she was started on therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin to prevent any further embolic manifestations of APLS. She was eventually bridged to warfarin for indefinite anticoagulation.

Outcome and follow-up

Though the patient’s dyspnoea and haemoptysis improved significantly over the course of her hospitalisation, she was ultimately discharged with home oxygen through a nasal cannula. Her vision did not improve as she retained a nasal visual field defect in her left eye on ophthalmology follow-up. Although the patient’s Osler’s nodes resolved within 1 week of discharge, her severe mitral regurgitation remained unchanged on future TTE. Due to lack of effective medical treatment and the severity of mitral regurgitation, cardiothoracic surgery for valve replacement may be necessary and active surveillance will be required. Confirmation of APLS diagnosis was obtained with elevated anticardiolipin and anti-B2 glycoprotein IgG several weeks later. She will require continued indefinite anticoagulation and should consider rituximab therapy in the future.

Discussion

APLS is a hypercoagulable state clinically characterised by arterial and venous thrombosis and pregnancy morbidity defined by fetal loss in the setting of laboratory evidence of antiphospholipid antibodies. Incidence is estimated at 5 new cases per 100 000 people per year leading to a prevalence of 0.04%–0.05% in the general population.1 APLS is more prevalent in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) than the general population; however, it is controversial as to whether ethnicity is at all related to prevalence. Some studies show differences, while others demonstrate no significant difference.2 In addition, APLS is more common in women. Because pregnancy mortality can be one of the defining features of the disease and pregnancy inherently is a hypercoagulable state, the typical presenting patient is often thought of as a female of reproductive age.3

Diagnosis of APLS is currently outlined by the Sydney International Consensus Classification Criteria defined by at least one clinical criteria (vascular thrombosis or pregnancy morbidity) and at least one laboratory criteria persistent on two separate occasions at least 12 weeks apart (positive lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibody IgG or IgM or AntiB2 glycoprotein-I IgG or IgM).4 5 Other non-criteria include thrombocytopaenia, cardiac valve dysfunction, DAH, cognitive dysfunction, skin ulcers and nephropathy.6 Our patient presented with multiple non-criteria manifestations of APLS including cardiac valve dysfunction and DAH. Throughout her hospital course, we discovered she did have one clinical criteria (retinal artery occlusion) and two laboratory criteria (elevated anticardiolipin IgG and anti-B2 glycoprotein IgG) which were even further elevated on repeat testing several weeks later. The clinical manifestations and persistently positive laboratory markers confirm the diagnosis of APLS and refute other causes of positive antiphospholipid antibodies, such as underlying ITP.7 Rarely, APLS can present with multiple non-criteria manifestations as our patient did.8 The pathogenesis of DAH is not clearly understood, but recent literature finds pulmonary capillaritis as a possible underlying mechanism.9–11 Deane et al postulated the pathophysiology of pulmonary capillaritis to be due to upregulation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules and complement activation by antiphospholipid antibodies, leading to neutrophil recruitment and ultimately tissue and vessel wall destruction causing haemorrhage.10 11 Many reported cases presented with neutrophilic infiltrate on bronchoalveolar lavage or biopsy, which was consistent with our patient’s presentation and supports capillaritis as the underlying pathology causing DAH.10 11 Cardiac valve dysfunction commonly impacts the mitral valve, again consistent with our patient’s presentation.12 The mechanism behind cardiac valve dysfunction is not known, but it is thought that antiphospholipid antibody deposition on heart valves promotes thrombus formation on already damaged valves, although the initial mechanism of valvular injury has not been defined.12 13 As reported by Pope et al, common clinical laboratory features in 14 patients with APLS, cerebral ischaemic events and endocardial lesions, the majority of these patients showed decreased C4 complement levels and some patients showed retinal vascular lesions, both of which were present in our patient.14 Thrombocytopaenia in the antiphospholipid patient is typically not clinically significant at <100 000/mm3.6 Our patient had severe thrombocytopaenia which is explained by previously diagnosed ITP. Although less commonly diagnosed, patients with ITP and concurrent APLS showed significantly less risk for thrombosis than did patients with APLS and SLE.15 This may partially explain our patient’s atypical presentation. It is possible our patient had more significant haemorrhage in the setting of concurrent thrombocytopaenia than she would have had secondary to antiphospholipid-induced damage to pulmonary vasculature alone. Of patients diagnosed ITP that do have antiphospholipid antibodies, presence of lupus anticoagulant was associated more strongly with arterial and venous thrombosis than was the presence of anticardiolipin antibodies.16

In patients with DAH secondary to APLS pulse dose intravenous steroids are first-line treatment. After recovery, immunosuppressive therapy can be considered to decrease the risk of recurrence.6 Our patient declined rituximab therapy. A retrospective analysis by Cartin-Ceba et al, studied the number of patients achieving partial or complete remission with immunosuppressive therapy in addition to high-dose corticosteroids: cyclophosphamide 4/7 patients responded, rituximab 2/5 responded, combination therapy rituximab and cyclophosphamide or mofetil led to 3/3 patients achieving complete remission. Patients treated with IVIG or plasma exchange had no remission.9 Concurrent APLS and DAH are additionally complex due to the need for anticoagulation in the setting of active bleeding. Current recommendations for treatment are to discontinue anticoagulation, begin high-dose corticosteroids and an immunosuppressive agent.6 9

Libman-Sacks endocarditis secondary to APLS has no known effective medical treatment.12 Corticosteroid therapy has no use in the prevention of valvular disease and treatment for existing valvular disease has shown variable results.12 13 This treatment has elicited concerns that valve healing may lead to scarring which worsens valvular dysfunction.12 13 Espinola-Zavaleta et al show that neither anticoagulant nor antithrombotic therapy is effective in promoting regression of cardiac vegetations.17 As such, further investigation into the pathogenesis and treatment of cardiac valve dysfunction in APLS is needed, as many patients, like our patient, will likely require surgical treatment.

Our case demonstrated the presentation of many seemingly independent, non-criteria symptoms grouped together led to the diagnosis of APLS. After ruling out more common causes of DAH, it is important to consider less common causes like APLS and their unusual presentations. Through this patient’s story, we hope to have shed light on one of the unusual presentations of APLS. Prompt diagnosis of APLS-induced DAH is the first step in initiating potentially life-saving treatment.

Learning points.

Consider antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS) in patients with concurrent diffuse alveolar haemorrhage and Libman-Sacks endocarditis with underlying autoimmune disorders.

APLS can present with symptoms that initially do not meet diagnostic criteria, but thorough history and physical examination can uncover symptoms which do meet clinical criteria for diagnosis.

Recognise that multiple seemingly unrelated problems, when grouped together may point to a unifying underlying condition.

Footnotes

Contributors: BB, NHS, DW and CS participated in this patient’s care and contributed to this work as a team. BB drafted the original manuscript, which was edited and critically revised by each team member. NHS and DW obtained relevant images and provided pertinent explanations. CS, the attending physician, modified and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gómez-Puerta JA, Cervera R. Diagnosis and classification of the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Autoimmun 2014;48-49:20–5. 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClain MT, Arbuckle MR, Heinlen LD, et al. The prevalence, onset, and clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies prior to diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1226–32. 10.1002/art.20120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 132: Antiphospholipid syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1514–21. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000423816.39542.0f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006;4:295–306. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardiner C, Hills J, Machin SJ, et al. Diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome in routine clinical practice. Lupus 2013;22:18–25. 10.1177/0961203312460722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erkan D, Lockshin MD. Non-criteria manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2010;19:424–7. 10.1177/0961203309360545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diz-Küçükkaya R, Hacihanefioğlu A, Yenerel M, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies and antiphospholipid syndrome in patients presenting with immune thrombocytopenic purpura: a prospective cohort study. Blood 2001;98:1760–4. 10.1182/blood.V98.6.1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hambly N, Sekhon S, McIvor RA. Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and Libman-Sacks endocarditis in the absence of prior thrombotic events. Ulster Med J 2014;83:47–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartin-Ceba R, Peikert T, Ashrani A, et al. Primary antiphospholipid syndrome-associated diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:301–10. 10.1002/acr.22109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isshiki T, Sugino K, Gocho K, et al. Primary antiphospholipid syndrome associated with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and pulmonary thromboembolism. Intern Med 2015;54:2029–33. 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deane KD, West SG. Antiphospholipid antibodies as a cause of pulmonary capillaritis and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: a case series and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2005;35:154–65. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenedios F, Erkan D, Lockshin MD. Cardiac involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2005;14:691–6. 10.1191/0961203305lu2202oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hojnik M, George J, Ziporen L, et al. Libman-Sacks Endocarditis in the Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Circulation 1996;93:1579–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pope JM, Canny CL, Bell DA. Cerebral ischemic events associated with endocarditis, retinal vascular disease, and lupus anticoagulant. Am J Med 1991;90:299–309. 10.1016/0002-9343(91)80009-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habe K, Wada H, Matsumoto T, et al. Presence of antiphospholipid antibodies as a risk factor for thrombotic events in patients with connective tissue diseases and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Intern Med 2016;55:589–95. 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.5536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moulis G, Audemard-Verger A, Arnaud L, et al. Risk of thrombosis in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia and antiphospholipid antibodies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev 2016;15:203–9. 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espínola-Zavaleta N, Vargas-Barrón J, Colmenares-Galvis T, et al. Echocardiographic evaluation of patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Am Heart J 1999;137:973–8. 10.1016/S0002-8703(99)70424-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]