Abstract

Purpose

To assess the immunohistochemical and histopathological changes in a subject with Autosomal Dominant Vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC).

Design

Case study.

Participant

Ninety two year-old Caucasian male with ADVIRC.

Methods

The subject was documented clinically for 54 Years. The retina/choroid complex of the right eye was evaluated with cryosections stained with hematoxylin and eosin or periodic acid schiff reagent. Cryosections were also evaluated with immunofluorescence or alkaline phosphatase immunohistochemistry (IHC) using primary antibodies against bestrophin1, GFAP, PEDF, RPE65, TGFβ, VEGF, and vimentin. The left retina and choroid were evaluated as flat mounts using immunofluorescence. UEA lectin was used to stain viable vasculature.

Main Outcome Measures

The immunohistochemical and histopathological changes in retina and choroid from a subject with ADVIRC.

Results

The subject had a heterozygous c.248G>A variant in exon 4 of the BEST1 gene. There was widespread chorioretinal degeneration and atrophy except for an island of spared RPE monolayer in the perimacula/macula OU. In this region, some photoreceptors were present, choriocapillaris was spared, and retinal pigment epithelial cells were in their normal disposition. There was a Muller cell periretinal membrane throughout much of the fundus. Bestrophin-1 was not detected or only minimally present by IHC in the ADVIRC RPE, even in the spared RPE area. Beyond the island of retained RPE monolayer on Bruch’s membrane (BrMb), there was migration of RPE into the neuro-retina, often ensheathing blood vessels and producing excessive matrix within their perivascular aggregations.

Conclusions

The primary defect in ADVIRC is in RPE, the only cells in the eye that express the BEST1 gene. The dysfunctional RPE cells may go through epithelial/mesenchymal transition as they migrate from BrMb to form papillary aggregations in the neuro-retina, often ensheathing blood vessels. This may be the reason for retinal blood vessel nonperfusion. Migration of RPE from BrMb was also associated with attenuation of the choriocapillaris.

Keywords: ADVIRC, Bestrophin-1, choriocapillaris, epiretinal membrane, retinal pigment epithelium, Müller cells, RPE cells, retinal and choroidal degeneration

Introduction

The initial sibship with family members affected by ADVIRC (Autosomal Dominant Vitreoretinochoroidopathy)(OMIM 193220) was reported 35 years ago.1 We provided the ADVIRC name at the time 1 and subsequently identified the causative mutation in the bestrophin-1 (BEST1) gene.2 The histopathological changes included atrophic retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), disorganization of the sensory retina, multifocal loss of photoreceptors, RPE ensheathment of retinal blood vessels, and preretinal membranes.3

Since the original publications, about 12 unrelated families have been reported with this rare disorder, all of which were associated with different mutations in the BEST1 gene.1, 4–9 Initially, the progression of ADVIRC seemed limited, but several subsequent reports, including our own, have shown progression of ophthalmoscopic and other ocular disorders to various extents.2, 10

This report describes the immunohistochemical and histopathologic abnormalities in the fundus tissues of the oldest known individual with ADVIRC (92 years at death). His advanced age and 54-year medical history allow a more complete description of the full spectrum and severity of this disease. This study evaluated the histopathological progression of ADVIRC and the abnormal expression of BEST1 in the RPE using immunohistochemistry. The results confirm RPE as the primary site of gene malfunction.

Methods

All procedures in this study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human tissue and were approved by the institutional review boards of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. The death to enucleation time for the eyes was 7.4 hours. The right eye was fixed immediately while the left eye was processed 47 hours postmortem. The right eye of this 92 year old subject was shipped to the Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute in 10% neutral buffered formalin fixation at 4°C, and the left eye arrived in a vial on wet ice. In addition, whole blood from the subject was shipped at 4°C for genomic analysis.

Tissue preparation

A cap was removed from the nasal side of the right globe, and then the anterior portion of the eye was removed as well. The cap and anterior eye were embedded in paraffin. The remainder of that eyecup was washed in several changes of 0.1M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, at 4°C. After examination and imaging, the posterior eyecup of the right eye was cut into calottes of the vitreous–retina–choroid complex and cryopreserved with increasing concentrations of sucrose, as previously described.11 Serial 8-μm thick cryosections were cut from the cryo blocks, collected in duplicate on glass slides coated with Vectabond (Vector, Burlingame, CA), dried, and stored at −80°C until immunohistochemistry was performed. Both hematoxylin (H) and eosin (E), as well as H and periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reagent, were used to stain paraffin sections and cryosections.

The anterior segment of the left eye also was removed after a circumferential incision, approximately 5 mm from the limbus. A dissecting microscope (Stemi 2000; Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY) with a mounted digital camera (Q-imaging, Vancouver, BC) was used for gross examination and photography of the posterior eyecup, and to capture high-resolution images. Images were imported directly into Adobe Creative Suites (ver. 6.0; Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA) on a PowerMac G5 (Apple Computer, Cupertino, CA).

Reflected and transmitted illuminations were used for photographic documentation prior to dissection. Vitreous was removed, and the sensory retina was then excised from the RPE/choroid OS. After removing the retina, the eyecup containing the choroid, with the RPE intact, was reimaged. The choroid was then dissected from the sclera, washed briefly in 0.1M cacodylate and fixed overnight in 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M cacodylate buffer at 4°C.

Immunohistochemistry and Imaging of Retinal and Choroidal Whole Mounts

The choroid OS was fixed, washed in TBS with 0.1% TritonX-100 and incubated, as described previously, with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated to Ulex europaeus agglutinin lectin (UEA stains blood vessels) for 48 hours at 4°C (Sigma L9006;1:100). 12 Immunofluorescence in the flat mounted choroid was imaged with a confocal microscope (710; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) at 488-nm excitation. Overlapping fields (10% overlap) were captured from the submacular region to the temporal peripheral choroid at 2048X2048 pixel resolution using Zen Software (2010, Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, New York). Percent vascular area determinations of choroidal vascular density were made as previously reported.12

The isolated retina OS was processed as previously described.13 Briefly, after overnight fixation, the tissue was washed and blocked overnight in 5% goat serum prepared in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% BSA (TBS-T/BSA). Tissues were incubated in primary antibodies prepared in TBS-T/BSA for 72 hrs at 4°C, and in secondary antibodies for 48 hours as published previously.13, 14 Peanut agglutinin (PNA) and UEA lectin were applied along with the secondary antibodies on some retinal and choroidal pieces. Antibodies utilized are listed in Table 1. Images were collected on a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope. After imaging, the retina and choroid were embedded in JB-4 or cryopreserved and sectioned (8 μm sections) for further analysis.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical Antibodies

| Antibody | Source | Dilution | Cells labeled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ms-a-RPE65 | ThermoFisher | 1:500 | RPE cells |

| Rb-a-VEGF | ThermoFisher | 1:200 | Growth factor |

| Ms-a-PEDF | Millipore | 1:200 | Growth factor |

| Rb-a-IBA1 | Wako | 1:500 | Macrophages, microglia |

| Rb-a-vimentin | Abcam | 1:200 | Müller cells |

| Rb-a-TGF beta | Abcam | 1:200 | Growth factor |

| Rb-a-Bestrophin 1 | Novus | 1:200 | RPE cells |

| Ck-a-vimentin | Millipore | 1:500 | Müller cells |

| Rb-a-GFAP | Dako | 1:500 | Astrocytes |

| Rb-a-AF647 | Invitrogen | 1:500 cryosections 1:200 flatmounts |

|

| Rb-a-cy3 | Jackson Immunoresearch | 1:500 cryosections 1:200 flatmounts |

|

| Ck-a-cy3 | Jackson Immunoresearch | 1:500 cryosections 1:200 flatmounts |

|

| Ms-cy3 | Jackson Immunoresearch | 1:500 cryosections 1:200 flatmounts |

|

| Ms-a-AF647 | Invitrogen | 1:500 cryosections 1:200 flatmounts |

|

| DAPI | Invitrogen | 1:1000 | Nuclei |

| Gt-a-Ms Biotin | KPL | 1:500 | |

| Streptavidin Alkaline Phosphatase | KPL | 1:500 | |

| Peanut Agglutinin | Vector | 1:500 | Photoreceptor segments |

| UEA lectin | Genetex | 1:100 | Endothelial cells/blood vessels |

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on Sections

Eight-micron cryosections of the ADVIRC right eye were immunolabeled with antibodies using both immunofluorescence and APase staining methods as described previously.15, 16 Cryosections from an aged control eye (71 year old Caucasian Male) from our archives were run in parallel with the ADVIRC tissue. Briefly, sections for immunofluorescence were air-dried and permeabilized in methanol for five minutes, then blocked in 2% goat serum for 20 min, and incubated in primary antibodies for 2 hrs at room temperature as published previously.16 Secondary antibodies (1:500) and DAPI (1:1000) were applied after washes, and sections were incubated for 30 minutes. RPE lipofuscin autofluorescence was quenched using 1% Sudan black B in 70% ETOH treatment following immunolabeling.17 After washing, sections were coverslipped with Dako Cytomation mounting media. Images were collected on a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope.

Melanin in RPE and melanocytes was bleached in sections stained with APase IHC as reported previously.15

Genetics

To confirm the diagnosis of ADVIRC, DNA was extracted from blood lymphocytes of this individual for sequence analysis of exon 4 of the BEST1 gene. This exon had been found in an earlier study to harbor a non-synonymous variant, c.248G>A (p.Gly83Asp), in his affected son, who was the proband of our initial report.1–3 The c.248G>A variant was shown to segregate with ADVIRC in the family and to represent a pathologic mutation affecting a highly conserved transmembrane domain in the BEST1 protein.

Results

Clinical background

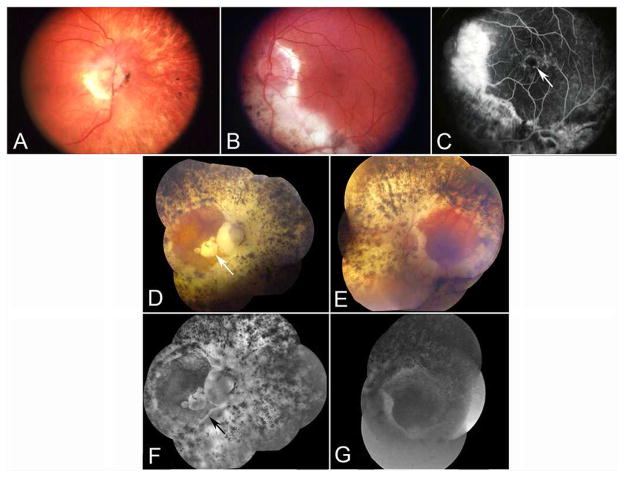

The ADVIRC subject was initially examined clinically at age 38, and some of his clinical data at age 55 were published as Case III-3 in our initial article that described the first pedigree of this rare disease and that also provided its name.1 At age 55, visual acuity was 20/30 OD and 20/20 OS. The peripheral fundi showed an annular distribution of widespread, intense pigmentary abnormalities between the ora serrata and the posterior pole of each eye. Although abnormalities were more prominent in the periphery of the fundi, there was no discrete pigmentary border located along the posterior margin of the degenerated fundus in this subject, unlike several other ADVIRC patients in his sibship and in others. The right fundus also showed mild to moderate retinal arteriolar narrowing, a gliotic membrane at the disc, and peripapillary areas of RPE atrophy and migration (Figure 1A). Visibility of large choroidal vessels in the peripapillary fundus suggested atrophy of both choriocapillaris (CC) and the RPE. The peripheral fundus showed areas of clumped hyper- and hypo-pigmentation as well as visibility of large choroidal vessels. Both maculas appeared normal ophthalmoscopically. The left optic disc had peripapillary atrophy, and there was a large area of severely atrophic retina and choroid, with clumped hyperpigmentation, that extended inferiorly from the left optic disc to the equator (Figure 1B). A fluorescein angiogram showed cystoid macular edema in the left eye and no perfusion in the peripheral retina (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

A and B) Fundus appearance of both eyes at age 55. Progression of optic atrophy, retinal vascular involution, and hyper- and hypopigmentation were marked. Note the onset of severe macular atrophy OD, with visualization of sclera within the macula and around the optic nerve.

C) Age 55, a fluorescein angiogram of the left eye. Note severe chorioretinal atrophy inferior to the left optic nerve. Mild cystoid macular edema is present (arrow).

D–G) Age 88, composite fundus photos and angiograms of both eyes. Note 360 degrees of severe chorioretinal atrophy and hyper- and hypopigmentation (with visible sclera) surrounding both discs. Macular atrophy (arrow in D) is present in the right eye. Also, note minimal or no retinal perfusion in late fluorescein angiogram of both eyes. The arrow in F shows the junction between residual RPE and atrophic RPE..

By age 68, he had developed nyctalopia and tunnel vision in both eyes. Visual acuity was 20/40 OD and 20/25 OS. For the first time, elevated intraocular pressures (52 mmHg OD and 29 mmHg OS) were detected. His angles were open gonioscopically. Cup-to-disc ratios were 0.7 OD and 0.4 OS. A diagnosis of open angle glaucoma was made in addition to the degeneration in his fundi. He was given a chronic course of topical anti-glaucoma medications, and, for the most part, intraocular pressures remained well within normal limits.

By age 71, despite regular monitoring and apparently successful treatment of intraocular pressures, visual acuity had fallen to 20/200 OD and 20/30 OS. Visual acuity in the right eye continued to fall to 20/400, then hand motions by age 80, light perception by age 83, and finally no light perception by age 86. He was last seen clinically at age 88. At that time, visual acuity was no light perception OD and 20/40 OS. Intraocular pressures were 14 mmHg OD and 12 mmHg OS. The cup-to-disc ratio was 0.99 OD, and the disc was “diffusely pale”; the left disc had a “better color.”

By age 88, the macula in the right eye had become severely atrophic clinically, and the peripapillary areas of hyper- and hypo-pigmentation had increased in intensity and area, both centripetally around the disc and also within the macula (Figure 1D). Similar changes had occurred in the left eye, although the central macula was relatively spared, thereby accounting for retention of reasonably good visual acuity in the left eye (Figure 1E). The retinal vasculature now showed marked narrowing bilaterally. A fluorescein angiogram revealed no visible retinal vascular perfusion in the right eye and almost no visible retinal flow in the left eye (Figure 1G). The relative contributions of the glaucoma and of the fundus dystrophy to the complete loss of vision OD could not be determined.

Genetics

DNA sequence analysis revealed the heterozygous c.248G>A variant in exon 4 of the BEST1 gene, predicted to result in the amino acid change p.Gly83Asp. This provides further evidence that this mutation is segregating in the family of the proband with the ADVIRC phenotype.1, 10 In addition, the mutation occurs within the second putative transmembrane domain of BEST1 and alters a nonpolar Glycine to a negatively charged Aspartic Acid within a membrane-spanning alpha helix region. In addition, the glycine residue at codon 83 is highly conserved from human to Xenopus and zebrafish. A similar mutation at this position (248G>C; Gly83Ala) has been associated with classical Best disease further supporting the pathogenicity of the c.248G>A (p.Gly83Asp) mutation.18 Finally, the c.248G>A mutation was not observed in the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/), a resource that provides sequence data from 123,136 exomes and 15,496 whole-genomes from unrelated individuals. Together, these findings strongly suggest that the c.248G>A mutation is a causal genetic variant linked to the ADVIRC phenotype in the proband’s family.

Gross and UEA Studies of the Choroid

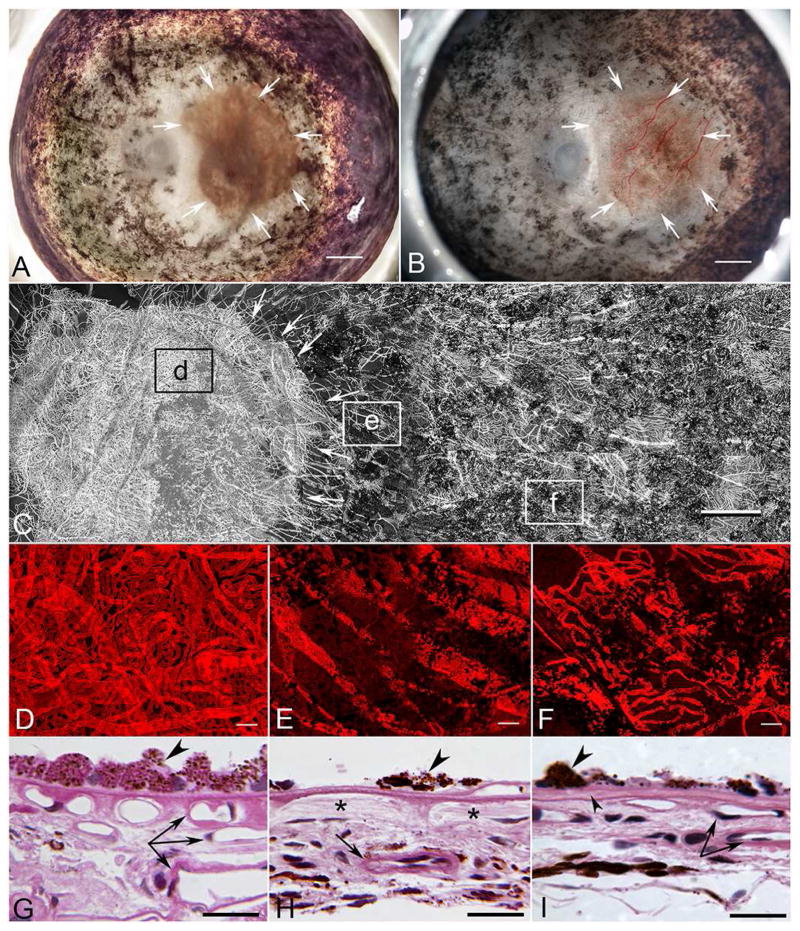

The posterior segment of the left eye (Figure 2A–B) had multifocal areas of both hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation extending from the pre-equatorial region to the ora serrata for 360 degrees. RPE in the macular region appeared intact and normally pigmented, occupying an area of 38 mm2 in the posterior pole. Bone spicule-like pigmentation was observed around the retinal vasculature for 360 degrees.

Figure 2. Gross photos and UEA-labelled choroidal whole mount of ADVIRC eye.

A&B) Gross photos of the left eye before (A) and after (B) removal of the neuro-retina. Arrows indicate a region of spared RPE atrophy and hypo- and hyperpigmentation elsewhere in the posterior pole (A) and blood-filled choroidal vasculature in this area after removal of the retina (B). Scale bar = 2mm.

C) Tiled panoramic confocal microscopic image of the choroidal vasculature labeled with UEA (Ulex europaeus agglutinin) lectin from the posterior pole, where RPE was spared (arrows), to the temporal periphery, where pigmentary degeneration and clumped hyperpigmented lesions were noted. Boxed areas (d–f) indicate regions shown in Figure 2 D–F. For better visualization of the vasculature, the blood vessels have been pseudocolored gray. Scale bar = 1mm.

D–F) Higher magnification of UEA stained choroid from boxed regions in “C” showing choroidal vasculature in the submacular region with spared RPE (D). Choroidal vessels are also seen anterior to the macular region (E) and in the equatorial region (F). Black profiles are clumped RPE still attached to Bruch’s membrane.

G–I) JB4 sections of left choroidal flat mount through the region shown in (D–F). G) Posterior pole shown in (D) with RPE cells (arrowhead) and three levels of viable blood vessels (arrows). H) Area shown in box (E), where there are hyper-pigmented sparse RPE cells (arrowhead) adjacent to area with migrated RPE and no viable choriocapillaris (*), but a larger viable choroidal blood vessel exists in more posterior choroid (arrow). I) An island of hypertrophic RPE (large arrowhead) (shown in F) on a delaminated Bruch’s membrane (small arrowhead). Under the island of RPE, there are some viable choriocapillaries and larger choroidal blood vessels (paired arrow). Scale bar = 50μm.

The choroidal vasculature appeared normal in the region of spared RPE in the posterior pole (boxed area “d” in Figure 2C). Choriocapillaris (CC), medium size vessels of Sattler’s layer, and large vessels of Haller’s layer were present (Figure 2D). The percent vascular area (vascular density) in this region was 80.8 +/−1.14%. The CC had a typical homogeneous, freely interconnecting pattern with broad-diameter lumens (13.2 +/−1.2 microns). Few degenerative capillary segments (UEA−) were present. In the region of hypopigmentation, just anterior to the spared RPE (boxed area “e” in Figure 2C), little if any CC was present, and only large choroidal vessels remained (Figure 2E). The percent vascular area was 20.2 +/− 2.6%. In the equator (boxed area “f” in Figure 2C), where multifocal areas of both hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation were noted in the gross examination, some moderate degeneration of CC was apparent (Figure 2F). The percent vascular area in this region was 36 +/− 4.5% and these regions had islands of surviving RPE. Cross sections of areas shown in Figure 2D–F demonstrate a normal choroidal vasculature under the RPE monolayer in the posterior pole (Figure 1G), while varying degrees of choroidal vascular atrophy were present where RPE had migrated from Bruch’s membrane (BrMb)(Figure 2H–I)

Retinal Histopathology

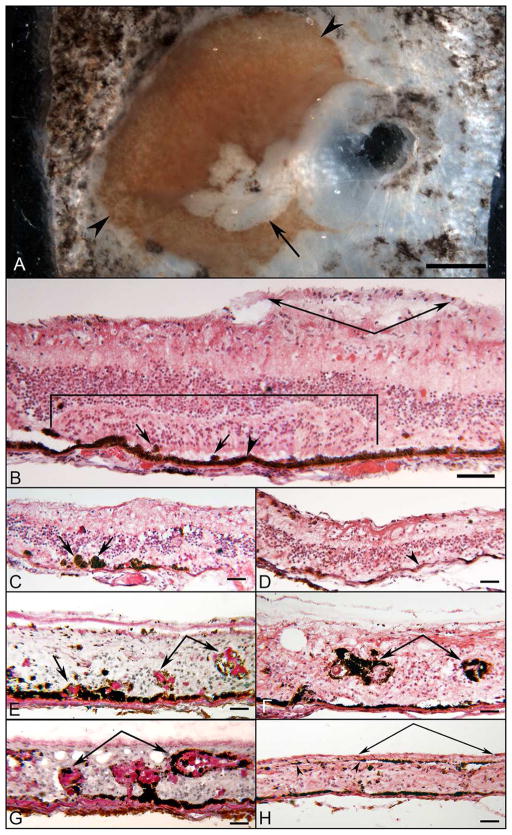

Figure 3 shows salient histopathological features of the posterior aspect of the right eye. Figure 3A is a photograph of the posterior pole block of the right eye before the tissue was frozen. A section through the superior portion of the area where RPE cells are spared in the posterior pole demonstrated a large cellular epiretinal membrane and somewhat disorganized laminar architecture of the retina (bracketed area in Figure 3B). The RPE cells in the posterior pole were largely cuboidal and heavily pigmented, but in the peripheral regions, the RPE was lightly pigmented (Figure 3D). Bruch’s membrane (BrMb) was continuous, but in the nasal and temporal periphery, thickening in BrMb was observed. The RPE varied somewhat in 4 different ways, shown in Figure 3C–H. First, the RPE was often missing, and the photoreceptor cells were frequently disorganized in some areas of the posterior pole (Figure 3C). Second, in other areas, photoreceptor cells were adjacent to bare BrMb; i.e. no RPE. Third, some cone inner segments could be identified extending from the external limiting membrane to the subretinal space. Fourth, outside of the spared area in the posterior pole, the RPE had migrated into the subretinal space and into different retinal layers (Figure 3 E–G). The evolution of acinar-like formations or papillary-like aggregations are shown in Figures 3E and G, which were stained with PAS and hematoxylin. The PAS staining showed the extensive production of matrix material within the “acini.” In the periphery, the RPE cells formed papillary aggregations with abundant basement membrane, extending into all layers of the retina, and seen surrounding the retinal blood vessels (Figures 3F–G). In the temporal retina (Figure 3H), the RPE had migrated to and lined the internal limiting membrane.

Figure 3. Gross photograph and H&E and PAS/Hematoxylin staining of right ADVIRC eye.

A) Postmortem block photo of right posterior eye before freezing. Note severe atrophy in macular region (arrow) and a circular zone of hyper- and hypo-pigmented RPE encroaching on the perimacular region (arrowheads). RPE is present in macula and perimacula. (Scale bar = 1 mm)

B) In the posterior pole of the right eye, the RPE appeared cuboidal and lined Bruch’s membrane (arrowhead). The photoreceptor nuclei were present in focal areas (bracketed region), where inner segments of mostly cone cells projected into the subretinal space. The laminar arrangement of the photoreceptor cells in the outer nuclear layer was disorganized. In other areas, the outer nuclear layer has disappeared (outside of bracket). Scattered ovoid, pigmented cells were seen in the subretinal space (arrows). The inner nuclear layer remained relatively organized, as was the inner plexiform layer. Few ganglion cells were seen. Anterior to the internal limiting membrane, a pre-retinal membrane was noted (paired arrows). The choroid is very thin but perfused. H&E.

C) At the equatorial region, the photoreceptor outer nuclear layer disappeared, but the inner nuclear layer remained. Heavily pigmented cells were seen in the subretinal space (arrows). There is no choriocapillaris in this very thin area of choroid. H&E.

D) Anterior to the equatorial area shown in ”C”, flattened and lightly pigmented RPE lined Bruch’s membrane (arrowhead). The photoreceptor cells have disappeared. The inner nuclear layer approximated the RPE. There is a thin preretinal membrane. H&E.

E) RPE cells of the nasal retina exhibited proliferative changes, initially as an elevated nodular arrangement with underlying thickened basement membrane material (arrow). More anteriorly, the RPE formed nodules of apparent papillary proliferation invading the inner nuclear layer (paired arrows). The retinal architecture was disrupted without definitive layers. PAS&H.

F) In the nasal retina, the abundance of hyperpigmented RPE in the papillary arrangement was observed with excessive basement membrane material in the inner layers of the retina surrounding blood vessels (paired arrows). H&E.

G) Papillary and perivascular arrangement of the RPE anterior to Bruch’s membrane extended into the inner layers of the nasal retina, with abundant PAS positive basement material (paired arrows). PAS&H.

H) The RPE was heavily pigmented in the far temporal retina. The retinal architecture was grossly disrupted without lamination. A thin layer of pigmented RPE cells lined the internal limiting membrane anteriorly (arrowheads) underlying an epiretinal membrane (paired arrows). H&E. Scale bars in all = 50μm.

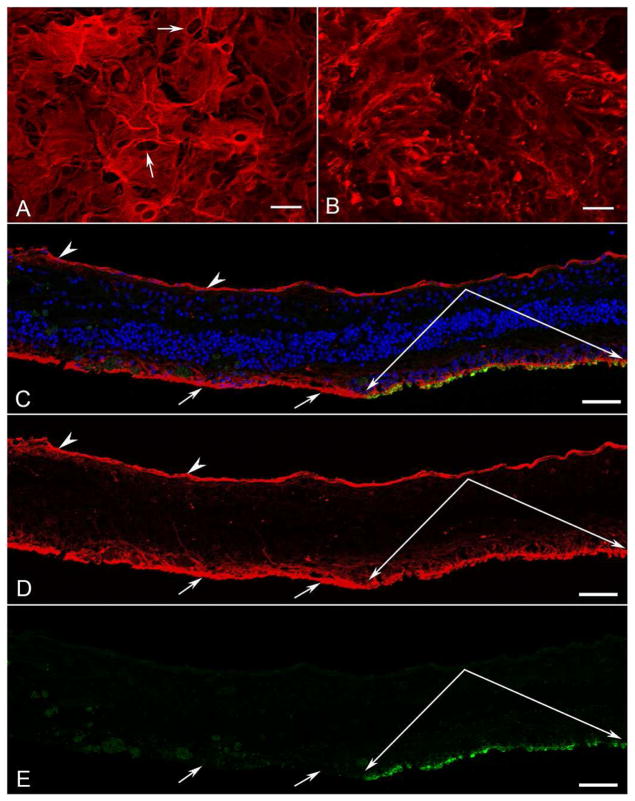

Retinal Flatmount

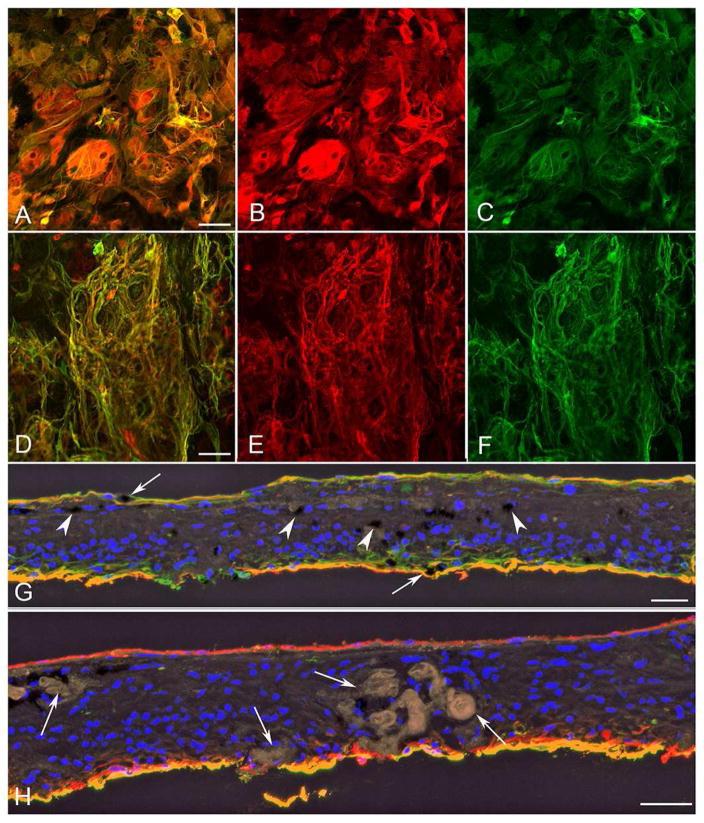

The retinal flatmount was divided into pieces for immunohistochemistry and imaging. Imaging of all retinal areas demonstrated a large glial membrane covering almost the entire internal surface of the retina (Figure 4). The membrane was densest outside the posterior pole. The parafoveal region was the only area of retina not covered by a preretinal membrane. The posterior pole of the flatmount retina was stained with vimentin (for Müller cells) and peanut agglutinin (PNA for cone sheaths). The epiretinal membrane contained not only vimentin+ glial processes but also numerous individual cells (Figure 4A). Pigmented RPE cells were also visible within the membrane. When the retina was imaged with the photoreceptor side up, a large subretinal membrane of vimentin+ processes was observed in areas lacking PNA-labeled photoreceptor segments (Figure 4B–E).

Figure 4. Posterior pole retina and membranes in left eye.

The posterior pole of the flatmount retina was stained for vimentin (red), peanut agglutinin (PNA, green), and DAPI (nuclei, blue). The retina was imaged in the flat perspective (A–B) and then cryopreserved and analyzed as cross sections (C–E).

A) Imaging of the retina with the nerve fiber layer up revealed a large glial membrane with numerous cell processes and individual nucleated cells positive for vimentin (arrows).

B) The same retina imaged with the photoreceptor side up demonstrated vimentin-positive Müller cell processes extending into the subretinal space, where PNA-positive photoreceptor segments were lost.

C–E) Cross sections of this same retina were analyzed to confirm that Müller cell processes were anterior to the ILM on the vitreoretinal surface (arrowheads) as well as in the subretinal space (arrows) in areas lacking PNA-positive photoreceptor segments. Paired arrows indicate surviving cone sheaths (green). [A–B vimentin (red); C and E PNA (green); C DAPI stained nuclei (blue)] Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

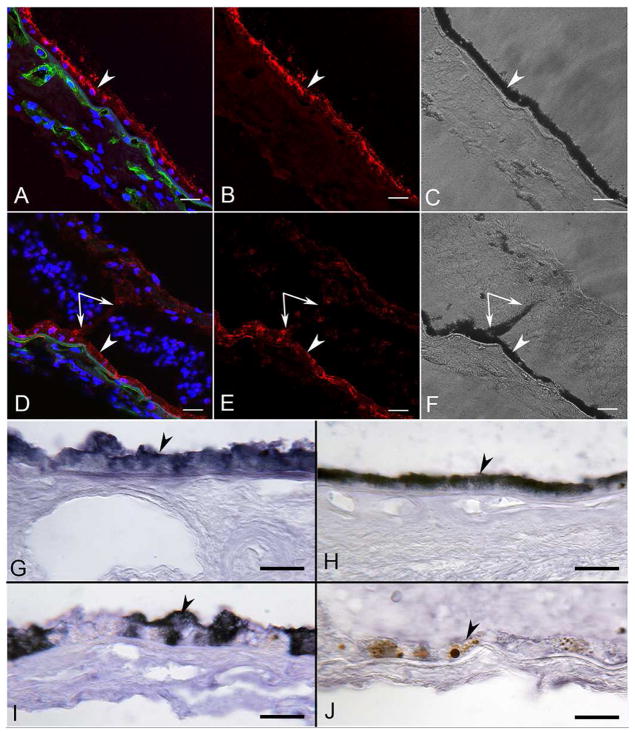

The temporal retina was labelled for vimentin and GFAP (for activated Müller cells and astrocytes)(Figure 5). Few distinctive astrocytes were observed within the retina. Most GFAP labelled cells were also positive for vimentin, suggesting they were activated Müller cells (Figure 5A–C). As mentioned above, the pre-retinal glial membrane covered almost the entire posterior pole area. A subretinal membrane was also observed in the temporal retina. Unlike the preretinal membrane, the subretinal membrane, as seen in the posterior pole, was mostly composed of cell processes (Figure 5D–F). In the periphery, the entire retina appeared to be completely gliotic. The dominance of Müller cells within the periretinal membranes was confirmed when the temporal retina was analyzed in cross section (Figure 5G–H). A distinctive preretinal membrane was observed. This was also observed in the inferior, superior and nasal portions of the retina (data not shown). DIC imaging revealed numerous blood vessels within the retina, which were surrounded by pigmented cells and activated Müller cells (Figure 5H). These acini or papillary aggregations, which were formed by migrated RPE cells, were also PAS-positive (Figure 3).

Figure 5. Temporal retina and membranes.

The temporal retina was stained for vimentin (red) and GFAP (green), and with UEA (Ulex europaeus agglutinin) lectin (yellow, shown in cross-section only).

A–C) Imaging of the retina with the nerve fiber layer up demonstrated a large glial membrane with vimentin/GFAP-double-positive (yellow) cells (A, merged; B, vimentin; C, GFAP)

D–F) A large subretinal membrane containing numerous GFAP/vimentin-double positive processes (yellow) was observed when imaging the retina with the photoreceptor side up. (D, merged; E, vimentin; F, GFAP)

G, H) Cross sections of the retinal area shown in A–F. G) The retinal lamination is lost in the temporal retina [note DAPI+ (blue) nuclei]. Müller cells are GFAP/vimentin-double positive (yellow) throughout the retina and have lost their anterior-posterior location. Pigmented cells (black; indicated by white arrowheads) were observed throughout the retina and within both the pre- and subretinal membranes (arrows). H) Pigmented cells and Müller cell processes surround amorphous structures (arrows). Very few astrocytes (GFAP-positive, vimentin-negative) were observed within the retina. (vimentin, red; GFAP green; colocalization of vimentin/GFAP, yellow; DAPI, blue; DIC black in H) Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

RPE Markers

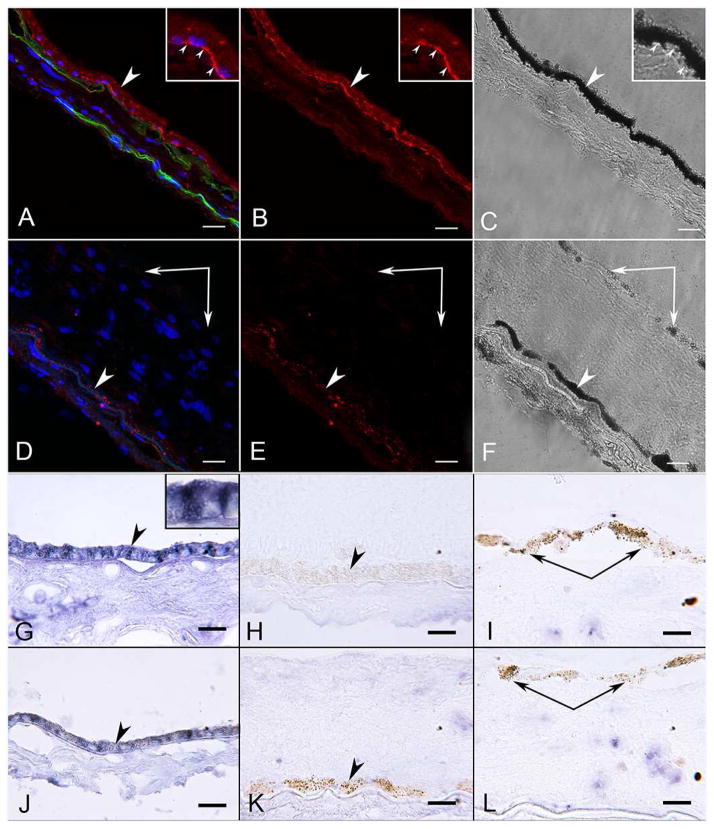

As anticipated, RPE65 was localized in all RPE cells in the aged control eye (Figure 6A–C). In the ADVIRC eye, RPE65 was observed in RPE lining BrM and to a much lesser degree in RPE that had migrated into the neural retina (Figure 6D–F). Using APase IHC, and then partially bleaching the melanin, permitted clear visualization of some level of RPE65 in pigmented cells in epiretinal membranes (data not shown). RPE in the ADVIRC posterior pole expressed RPE65, whereas those on Bruch’s membrane in the periphery had very little (Figure 6I and J). Anti-bestrophin-1 labeled all RPE in the aged control (Figure 7A–C). In the aged control, there was no difference in bestrophin-1 staining intensity in the macular RPE (compare Fig. 7G) as compared to the peripheral RPE (Figure 7J). In the ADVIRC eye, however, bestrophin-1 was not detected or only minimally present in the RPE, using both immunofluorescence (Figure 7D–F) and APase immunostaining (Figure 7H–I and K–L). This was true both in the macular (Figure 7H–I) and peripheral RPE (Figure 7K–L). None of the pigmented cells in epiretinal membranes had demonstrable bestrophin-1 immunoreactivity (Fig. 7D–E, I and L).

Figure 6. RPE65 immunofluorescence and APase in aged control and ADVIRC eyes.

RPE65 immunoreactivity (red) in an aged control (A–C) was localized in all retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells lining Bruch’s Membrane (arrowhead). Choriocapillaris (UEA+, green) is normal. In the ADVIRC eye (D–F), RPE65 was expressed in RPE on Bruch’s Membrane (arrowhead) and to a much lesser degree in RPE that had migrated into sensory retina (paired arrows).

G–H) APase immunohistochemical reaction product (blue) of RPE65 in control subject in macula (G) and periphery (H) is confined to the RPE.

I–J) APase immunohistochemistry of RPE65 in the ADVIRC eye in macula (I) and periphery (J). Blue RPE65 is reduced in macula and absent in periphery. Note the macromelanosome in the RPE (arrowhead in J) demonstrating extreme RPE dysfunction. (A&D: DAPI blue, RPE65 red, UEA lectin green; B&E RPE65; C&F DIC; G–J blue APase reaction product after partial bleaching of pigment). (Scale bars = 20μm in all)

Figure 7. Bestrophin-1 immunofluorescence and APase immunohistochemistry in aged control and ADVIRC eye.

A–C) Macula of control subject had bestrophin-1 (red) prominently in basal RPE. Choriocapillaris and larger choroidal vessels are apparent (green, UEA). Insets demonstrate clearly the basal location of bestrophin-1 (small arrowheads). (A, merged; B, bestrophin, red; C, DIC to demonstrate pigment in the RPE; Sudan black used to quench autofluorescence).

D–F) Perimacular region of the ADVIRC eye. Bestrophin-1 labeling is barely detectable in the ADVIRC RPE on Bruch’s membrane (arrowhead) and not present in RPE on the internal membrane (double arrow).(A, merged; B, bestrophin-1, red; C, DIC to demonstrate pigment; Sudan black used to quench autofluorescence).

G–L) Bestrophin-1 APase immunoreactivity (blue reaction product) in the macular region (G) and the temporal periphery of an aged control (J) showing basolateral localization (inset) in all RPE cells lining Bruch’s Membrane (arrowheads). No bestrophin-1 immunoreactivity was observed in the macular RPE (arrowhead in H) or temporal peripheral RPE (arrowhead in K) of the ADVIRC eye. Epiretinal pigmented cells (paired arrows in I&L) in the macula (I) and temporal periphery (L) of the ADVIRC eye were bestrophin-1 negative. (Blue APase reaction product after partial bleaching) Scale bars = 20μm in all.

Growth Factors/Macrophages

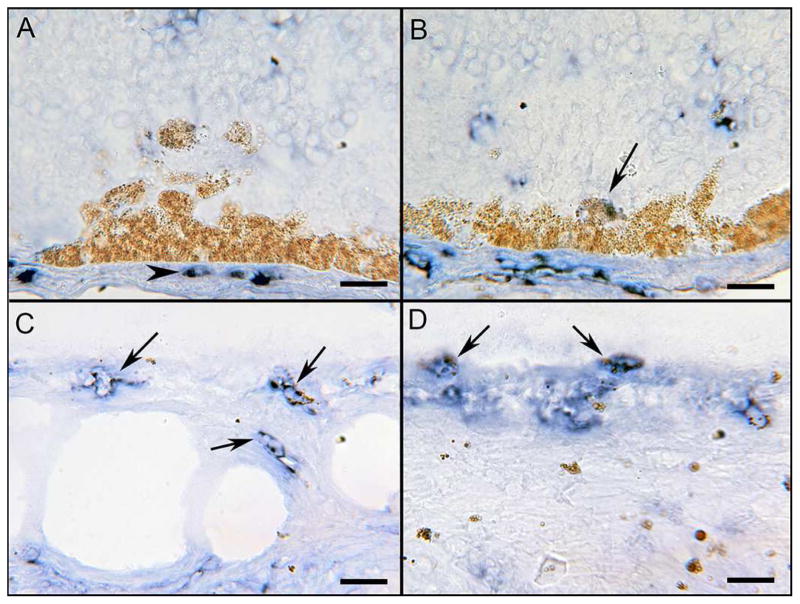

An important question concerns the origin of the pigmented cells; are they RPE cells or macrophage/microglia cells that have phagocytosed dying RPE cells? Ionized calcium binding adapter protein-1 (IBA-1) IHC with partial bleaching was used to determine if pigmented cells were either RPE or macrophage/microglia cells (IBA-1+). In the ADVIRC eye, IBA-1 was observed in scattered macrophages of the choroid (Figure 8A). Most rounded large pigmented cells in the outer retina were IBA-1 negative except for an occasional weakly stained cell (Figure 8B), suggesting that these cells are RPE and not macrophages. Numerous small pigmented macrophages (IBA1+) were observed in the inner retina (Figure 8C) and in epiretinal membranes (Figure 8D), but the large pigmented cells were not macrophages (IBA1−).

Figure 8. IBA-1 APase immunohistochemistry in ADVIRC eye.

IBA-1 (blue reaction product), a marker for microglia and macrophages, was observed in scattered macrophages of the choroid (arrowhead in A). Most rounded pigmented cells in the outer retina were IBA-1 negative (confirming them as RPE), except for an occasional weakly stained cell (arrow in B). Numerous small weakly pigmented macrophages (IBA-1+ with melanin) were observed in inner retina (arrows in C) and in epiretinal membranes (arrows in D). Scale bars = 20μm

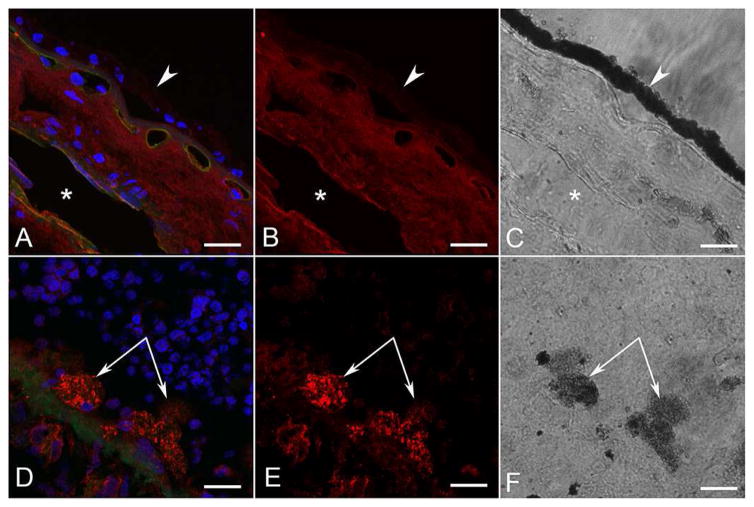

TGFβ is a chemoattractant for macrophages and also signals epithelial to mesenchyme transition as well as scar formation.19 In the choroid, there was diffuse TGFβ labeling in both the control (Figure 9A–B) and in the ADVIRC eye (Figure 9D–E). There was minimal expression of TGFβ in within the RPE monolayer in the ADVIRC subject. A key observation was the prominent expression of TGFβ in RPE cells that had begun their migration from BrMb (Fig. 9D–F), a trait of RPE cells in epithelial to mesenchymal transition.

Figure 9. Confocal microscopy of TGF β immunofluorescence in aged control and ADVIRC eyes.

TGFβ immunoreactivity (red) in the control (A&B) is localized in the choroidal stroma and in a vein (asterisk). RPE cells lining Bruch’s Membrane (arrowheads in A–C) were unlabeled. In the ADVIRC eye (D–F), TGFβ (red in D&E) was barely detectable in the RPE monolayer on Bruch’s Membrane, but was prominently observed in some rounded large, lightly pigmented cells, presumably RPE, beginning to migrate into neuro-retina (paired arrows in D–F). (A&D DAPI blue, TGFβ red, UEA lectin green, B&E TGFβ only, C&F DIC). Scale bars = 20mm

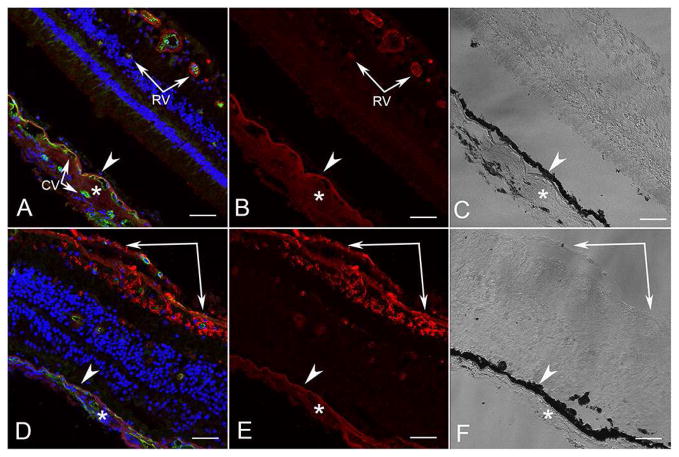

VEGF immunoreactivity in the control (Figure 10A–C) was localized to choroidal stroma and retinal blood vessels, as reported previously.20 In the ADVIRC eye (Figure 10D–F), VEGF immunoreactivity was observed in the choroidal stroma, but was most intense in inner retinal glia and epiretinal membranes on the inner aspect of the internal limiting membrane (Figure 10D–F).

Figure 10. Confocal microscopy of VEGF immunofluorescence in aged control and ADVIRC eye.

VEGF immunoreactivity (red) in an aged control (A–C) was localized to choroidal stroma (*) and Bruchs membrane external to RPE (arrowhead) and in retinal blood vessels (arrow). In the ADVIRC eye (D–F), VEGF immunoreactivity was observed in the choroidal stroma (*) but was reduced external to RPE (arrowhead). It was most intense in inner retinal glia and epiretinal membrane on the inner aspect of the internal limiting membrane (paired arrows). (RV, retinal vessel; CV, choroidal vessel)[A&D DAPI blue, VEGF red, UEA (Ulex europaeus agglutinin) lectin green; B&E VEGF; C&F DIC]. Scale bars = 50μm.

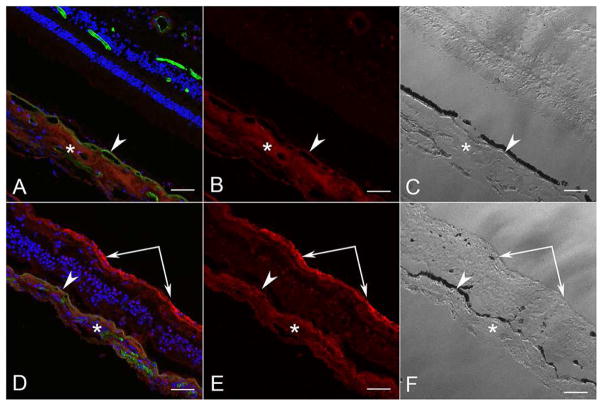

Immunostaining with pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) was primarily confined to the choroidal stroma in the aged control, as we have reported previously (Figure 11A–C) 21. The retina of the control had little to no demonstrable PEDF immunoreactivity. In the ADVIRC eye, choroidal stromal PEDF immunolabeling was slightly increased compared to the control. Staining for PEDF in the inner retina and in the epiretinal membrane was very pronounced in the ADVIRC eye (Figure 11D–F).

Figure 11. Confocal microscopy of PEDF immunofluorescence in aged control and ADVIRC eye.

PEDF (pigment epithelium-derived factor) immunoreactivity (red) in an aged control (AC) was localized to choroidal stroma (*) and external to RPE (arrowhead). Very little PEDF was observed in the control retina. In the ADVIRC eye (D–F), PEDF immunoreactivity was increased in the choroidal stroma (*) and external to RPE (arrowhead), but was most intense in the epiretinal membrane on the inner aspect of the internal limiting membrane (paired arrows). [A&D DAPI blue; PEDF red; UEA (Ulex europaeus agglutinin) lectin green; B&E PEDF; C&F DIC]. Scale bars = 50μm.

Discussion

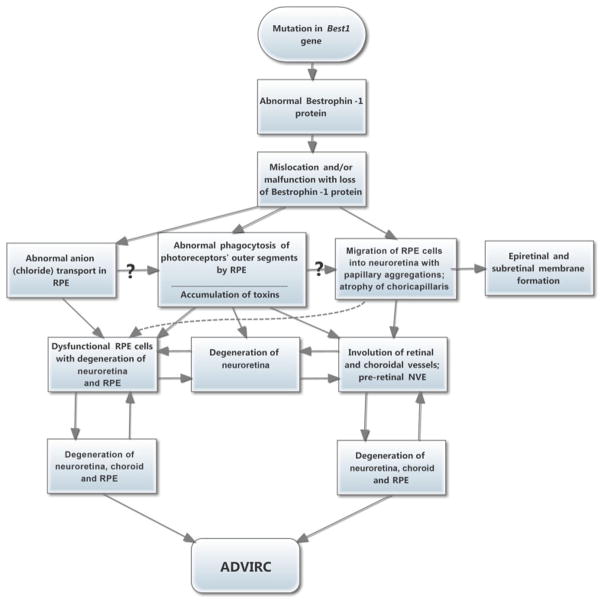

In the adult human eye BEST1 gene expression is exclusively observed in RPE cells. The bestrophin-1 protein forms a homo-pentameric22, Ca2+ activated Cl− channel 23, and is indispensable for volume regulation in human RPE cells.24 Over 200 individual mutations in the BEST1 gene have been discovered in recent years, and the diseases resulting from these mutations have been lumped under the name “bestrophinopathies.” Several BEST1 mutations cause ADVIRC (OMIM 193220).1, 25 Although other bestrophinopathies cause a spectrum of pathological disease phenotypes, including submacular fluid or abnormal materials, as well as central retinal degeneration, such as classical Best disease, none has a phenotypic appearance similar to that of ADVIRC.26 We report herein the oldest clinically documented ADVIRC subject to date. Our studies used modern pathological techniques to document dysfunction in the RPE that resulted in choroidopathy as well as neuro-retinal degeneration, vascular nonperfusion, and epiretinal and subretinal membranes (summarized in Figure 12). These periretinal membranes (epi- and sub-retinal) are predominantly made of migrated Muller cells and scattered RPE cells and have been observed in several retinal degenerations.13, 14

Figure 12. Flow chart showing possible pathogeneses of ADVIRC.

Hypothetical pathogenetic sequences in ADVIRC.

Bestrophinopathies, including ADVIRC 27, 28, have abnormal RPE cells containing genetically altered BEST1 that has “mislocated” away from its typical basolateral location (where it normally functions physiologically) into dispersed intracytoplasmic and also apical locations.29 As a consequence of these anatomic abnormalities, many basic biologic functions influenced by the RPE and by BEST1 do not occur normally in bestrophinopathies. For example, defective anionic transport (which normally occurs at the basolateral portions of the RPE) contributes to the abnormal EOG that characterizes most bestrophinopathies, including ADVIRC.9, 17, 26–29

An important issue that appears to be at the heart of ADVIRC and other bestrophinopaties relates to the RPE migration from BrMb into the neuro-retina and into the epiretinal membrane. Despite the advanced age of the ADVIRC subject, BrMb appeared normal. Interestingly, the ophthalmoscopically visible and apparently uniform appearance of the RPE in normal eyes suggests, falsely, that it is a monolithic layer of cells that are anatomically and embryologically identical. Several lines of evidence suggest, to the contrary, that the peripheral RPE is both morphologically and developmentally different from the central RPE.30–32 These regional variations might explain the iconic ophthalmoscopic differences in the peripheral versus the central RPE in ADVIRC (in the periphery of the fundus, obvious accentuation of the dystrophic processes is characteristic). Immunohistochemically, Carter et al and Mullins et al found greater expression of BEST1 in the peripheral RPE, compared to the central RPE.17, 27 Interestingly, we did not see a difference between these areas in the control subject used in this study. The ADVIRC subject had virtually no expression of BEST1 by immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 7). Taken together, these observations, coupled with those anatomic and functional abnormalities described above, provide phenomenologic and some pathogenetic evidence to explain, at least partially, the unique clinical appearance of the fundus in ADVIRC: its pathognomonic peripheral, annular zone of severe hyperpigmentation, atrophy, and vascular involution. This is in distinction to classic Best’s Vitelliform Macular Dystrophy (the prototype of bestrophinopathies) with its distinctly less severe disease in the periphery of the fundus. The observation of upregulation of TGFβ in RPE cells that are moving off of BrMb suggests that these RPE cells are going through epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT). This alone is enough to stimulate RPE migration. When expression of TGFβ is upregulated in mice, RPE EMT occurs early in life, similar to findings in the peripheral retina in our ADVIRC subject.19 Further support for EMT and, therefore, dedifferentiation is that the RPE cells cease making RPE65 (a characteristic of normal RPE) once they start to migrate into the neuro-retina (Figure 6) and possibly before.

RPE migration causes many of the pathological outcomes observed clinically in the ADVIRC fundus. The characteristically broad, circumferential hyperpigmented fundus band in ADVIRC is typically bordered on its central side by a very narrow circumferential hypopigmented band, which markedly hyperfluoresces during fluorescein angiography (Kaufman Figure 3 and 5 1; Han et al color Figure 3 33; and Roider Figure 1b 6). This narrow band of tissue appears to be the most recent and active zone of transformation of normal RPE cells into dysfunctional or perhaps dedifferentiated RPE. It is also a zone of severe loss of viable CC (loss of UEA staining in CC). Although this narrow curvilinear band “stains” brightly on fluorescein angiography, it appears not to “leak” (based on the hyperfluorescence not expanding). It is, therefore, a window defect caused by the loss of dystrophic RPE and by depigmentation of RPE, allowing easy visualization of the intact, more externally located choroidal blood vessels. We have observed severe attenuation of CC where RPE is lost in geographic atrophy 12, 34 and in Stargardt disease (D.S. McLeod unpublished). Because the CC is relatively normal in our subject, where RPE cells remain on BrMb in the posterior pole, and because the CC is absent adjacent to where RPE cells have vacated BrMb, it is reasonable to assume that RPE dysfunction and migration cause the choroidal vascular atrophy. This is logical, because RPE cells normally provide constitutive VEGF to keep CC viable under normal conditions and, when RPE VEGF is knocked out genetically, CC atrophy occurs.35, 36

Migration of the RPE cells into the neuro-retina also results in acinar-like formation or papillary aggregation. In and around these formations are large deposits of acellular matrix. These formations often ensheath retinal blood vessels, contributing to clinically observed bone spicule-like formations and depositing excessive matrix abluminally. It is unclear how damaging this excess matrix material is to the retinal blood vessels, but it results in almost a hyalinization of the vascular walls. This is similar to bone-spicule formations seen in retinitis pigmentosa subjects where the retinal blood vessels within the spicule formation become occluded with the matrix material.37 The acinar-like formations in outer retina that had a matrix core were similar to formations we observed in black sunburst lesions of sickle cell retinopathy subjects in that they were not associated with retinal blood vessels.38 Also, RPE dysfunction may cause an imbalance in growth factors that are supplied by the RPE and that may influence the viability of these blood vessels. These growth factors may include upregulated PEDF and also TGFβ, with vaso-inhibitory properties, as well as upregulated VEGF, with vaso-stimulatory influences, although other growth factors may also be involved. Mutual antagonism of these and other growth factors in the retina and choroid are well-known 39, 40 and, normally, a proper balance among them is established. We observed greatly elevated PEDF and VEGF in the inner retina and the epiretinal membrane in the ADVIRC subject, compared to the control subject. Theoretical and visible manifestations of the abnormal presence and function of PEDF and VEGF in these locations may respectively include the severe vascular involution observed in the neuro-retina in our present case (assuming that active PEDF exceeded the functional level of VEGF), as well as the preretinal neovascularization observed in some other cases of ADVIRC41, including our original proband.1 The contributing role of RPE ensheathment in vascular involution has been nicely demonstrated by a study in mouse by Uyama et al 42 and a study in monkey by Ryan et al 43, where involution of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization occurred when RPE ensheathed choroidal neovascularization, suggesting that RPE cells make an inhibitor of endothelial cells.44

As in other retinal degenerations like AMD13, 14, glial remodeling and proliferation occurred in the ADVIRC retina. In this tissue, not only was the peripheral retina characterized by a gliotic mass with acinar-like formations, but also extensive periretinal membranes were observed. In the right eye, there was a preretinal glial mass over part of the posterior pole (Figure 1). Moreover, there was an epiretinal membrane that contained predominantly Müller cells (vimentin+) throughout both fundi. The membranes also had microglia/macrophages (IBA1+) as well as RPE cells (Figure 8). It was striking in some areas that migrated RPE cells lined up on the ILM, perhaps using ILM as an alternative to BrMb. In addition, a subretinal membrane of Müller cells was also present, where photoreceptors had been lost. We have observed similar findings in geographic atrophy.14 The preretinal membranes had Müller cell somas, whereas the subretinal membranes were composed mostly of processes from the Müller cells (Figure 5).

It is not understood why different BEST1 mutations result in the panoply of quite dissimilar bestrophinopathies with dramatically different histologic and clinical phenotypes. The current subject had a heterozygous pathologic BEST-1 mutation, c.248G>A (p.Gly83Asp). Interestingly, there was a marked deficiency of any BEST1 expression in the RPE of our ADVIRC subject, as seen with immunohistochemistry. That could mean that c.248G>A leads to a loss of protein synthesis or that the expressed protein is fully degraded, including the non-mutated BEST1 copy. Supporting the latter are findings in RPE cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells of Best disease patients, which show that, depending on the specific mutation, the protein is mislocalized to the cytoplasm and severely reduced in expression.24, 28

In conclusion, the primary defect in this ADVIRC subject is in the RPE. Our hypothesis on the pathogenetic sequences in ADVIRC are summarized in Figure 12. When RPE cells vacate BrMb, CC lose their source of VEGF, and they degenerate. This was most pronounced adjacent to an island of relatively spared RPE in the posterior pole of our subject’s eyes, where RPE cells remain as a monolayer, and where the neuro-retinal layers are relatively intact. Because dysfunctional RPE cells are present, the neuro-retina is not completely normal in this island. Glaucoma also contributes to the abnormalities in the neuro-retina in this island but abnormalities in the retina and choroid outside the island are probably due to the Bestrophin1 mutation in RPE. However, once RPE cells vacate, normal phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments is no longer possible, and severe retinal degeneration ensues. The reason for vaso-occlusion in the neuro-retina is not completely clear, but RPE ensheathment of blood vessels and deposition of matrix in the abluminal niche may contribute to the vasculopathy. The degenerative process in our case study apparently also activates the retinal Müller cells, which form membranes above and below the neural retina, and which often have RPE cells associated with them. The questions that remain include the following: why is the most severely attenuated choriocapillaris located adjacent to the island of surviving RPE monolayer and relatively intact retina (Figure 2)? Did the disease progression stall and the area adjacent to the surviving island have more extensive loss of CC because of the long time frame without RPE cells on BrMb? Also, why is the central retina last affected and still remain relatively intact at 92 years of age? The observation of longevity of retinal survival in the posterior pole (at least in one eye), as well as in choroid, suggests that future gene therapy (e.g., replacing mutant BEST1), possibly in conjunction with stem cell therapy, may be applicable even into adulthood, and may prolong remaining vision thereafter.

Finally, because RPE is the source of the primary defect, the term “ADVIRC” is obviously an incomplete acronym for this disease. The term “ADVIRC-RPE” (Autosomal Dominant Vitreo-Retino-Choroido-Retinal Pigment Epitheliopathy), although longer and somewhat more awkward, accurately depicts the entire fundus spectrum of this fascinating disorder.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the family of the subject reported herein for willingness and persistence in donating the eyes. The authors also acknowledge Etienne Schonbach, M.D., and Adam Wenick, M.D., Ph.D., for assistance in editing the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants EY016151 (GL), EY01765 (Wilmer); the Altsheler-Durell Foundation, Foundation Fighting Blindness, and an RPB Unrestricted Grant (Wilmer)

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- APase

Alkaline phosphatase

- ADVIRC

Autosomal Dominant Vitreoretinochoroidopathy

- BEST1

bestrophin1

- BSA

bovine serum albumen

- BrMb

Bruch’s membrane

- CC

choriocapillaris

- DAPI

4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DIC

differential interference contrast microscopy

- GFAP

glial fibrillary protein

- PNA

peanut agglutinin

- PAS

periodic acid Schiff reagent

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- UEA

Ulex europaeus agglutinin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaufman SJ, Goldberg MF, Orth DH, et al. Autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982;100(2):272–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1982.01030030274008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CJ, Goldberg MF. Progressive Cone Dysfunction and Geographic Atrophy of the Macula in Late Stage Autosomal Dominant Vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37(1):81–5. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2014.889171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg MF, Lee FL, Tso MO, Fishman GA. Histopathologic study of autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy. Peripheral annular pigmentary dystrophy of the retina. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(12):1736–46. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kellner S, Stohr H, Fiebig B, et al. Fundus Autofluorescence and SD-OCT Document Rapid Progression in Autosomal Dominant Vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Associated with a c. 256G > A Mutation in BEST1. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37(2):201–8. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2015.1033556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lafaut BA, Loeys B, Leroy BP, et al. Clinical and electrophysiological findings in autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy: report of a new pedigree. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239(8):575–82. doi: 10.1007/s004170100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roider J, Fritsch E, Hoerauf H, et al. Autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy. Retina. 1997;17(4):294–9. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199707000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traboulsi EI, Payne JW. Autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy. Report of the third family. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(2):194–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090020048021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent A, McAlister C, Vandenhoven C, Heon E. BEST1-related autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy: a degenerative disease with a range of developmental ocular anomalies. Eye (Lond) 2011;25(1):113–8. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yardley J, Leroy BP, Hart-Holden N, et al. Mutations of VMD2 splicing regulators cause nanophthalmos and autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(10):3683–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CJ, Kaufman S, Packo K, et al. Long-Term Macular Changes in the First Proband of Autosomal Dominant Vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Due to a Newly Identified Mutation in BEST1. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37(1):102–8. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2015.1039893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lutty GA, Merges C, Threlkeld AB, et al. Heterogeneity in localization of isoforms of TGF-beta in human retina, vitreous, and choroid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(3):477–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seddon JM, McLeod DS, Bhutto IA, et al. Histopathological Insights Into Choroidal Vascular Loss in Clinically Documented Cases of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016;134(11):1272–80. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards MM, McLeod DS, Bhutto IA, et al. Idiopathic preretinal glia in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2016;150:44–61. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards MM, McLeod DS, Bhutto IA, et al. Subretinal Glial Membranes in Eyes With Geographic Atrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(3):1352–67. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-21229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhutto IA, Kim SY, McLeod DS, et al. Localization of collagen XVIII and the endostatin portion of collagen XVIII in aged human control eyes and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1544–52. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLeod DS, Hasegawa T, Baba T, et al. From blood islands to blood vessels: morphologic observations and expression of key molecules during hyaloid vascular system development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(13):7912–27. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullins RF, Kuehn MH, Faidley EA, et al. Differential macular and peripheral expression of bestrophin in human eyes and its implication for best disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(7):3372–80. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alapati A, Goetz K, Suk J, et al. Molecular diagnostic testing by eyeGENE: analysis of patients with hereditary retinal dystrophy phenotypes involving central vision loss. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(9):5510–21. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohlmann A, Scholz M, Koch M, Tamm ER. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition of the retinal pigment epithelium causes choriocapillaris atrophy. Histochem Cell Biol. 2016;146(6):769–80. doi: 10.1007/s00418-016-1461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutty GA, McLeod DS, Merges C, et al. Localization of VEGF in human retina and choroid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:971–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140179011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhutto IA, McLeod DS, Hasegawa T, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in aged human choroid and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane Dickson V, Pedi L, Long SB. Structure and insights into the function of a Ca(2+)-activated Cl(−) channel. Nature. 2014;516(7530):213–8. doi: 10.1038/nature13913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moshfegh Y, Velez G, Li Y, et al. BESTROPHIN1 mutations cause defective chloride conductance in patient stem cell-derived RPE. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(13):2672–80. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milenkovic A, Brandl C, Milenkovic VM, et al. Bestrophin 1 is indispensable for volume regulation in human retinal pigment epithelium cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(20):E2630–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418840112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrukhin K, Koisti MJ, Bakall B, et al. Identification of the gene responsible for Best macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998;19(3):241–7. doi: 10.1038/915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bakall B, Marknell T, Ingvast S, et al. The mutation spectrum of the bestrophin protein--functional implications. Hum Genet. 1999;104(5):383–9. doi: 10.1007/s004390050972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter DA, Smart MJ, Letton WV, et al. Mislocalisation of BEST1 in iPSC-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells from a family with autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Sci Rep. 2016;6:33792. doi: 10.1038/srep33792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milenkovic VM, Rohrl E, Weber BH, Strauss O. Disease-associated missense mutations in bestrophin-1 affect cellular trafficking and anion conductance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 17):2988–96. doi: 10.1242/jcs.085878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marmorstein AD, Marmorstein LY, Rayborn M, et al. Bestrophin, the product of the Best vitelliform macular dystrophy gene (VMD2), localizes to the basolateral plasma membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(23):12758–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220402097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tso MO, Friedman E. The retinal pigment epithelium. I. Comparative histology. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;78(5):641–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980030643016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tso MO, Friedman E. The retinal pigment epithelium. 3. Growth and development. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;80(2):214–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1968.00980050216012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moshiri A, Scholl HP, Canto-Soler MV, Goldberg MF. Morphogenetic model for radial streaking in the fundus of the carrier state of X-linked albinism. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(5):691–3. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han DP, Lewandowski MF. Electro-oculography in autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(11):1563–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080230063021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLeod DS, Grebe R, Bhutto I, et al. Relationship between RPE and choriocapillaris in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(10):4982–91. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marneros AG, Fan J, Yokoyama Y, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in the retinal pigment epithelium is essential for choriocapillaris development and visual function. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(5):1451–9. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61231-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saint-Geniez M, Maldonado AE, D’Amore PA. VEGF expression and receptor activation in the choroid during development and in the adult. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(7):3135–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li ZY, Possin DE, Milam AH. Histopathology of bone spicule pigmentation in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(5):805–16. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30953-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLeod DS, Goldberg MF, Lutty GA. Dual-perspective analysis of vascular formations in sickle cell retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(9):1234–45. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090090086026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao J, Kunz Mathews M, McLeod DS, et al. Angiogenic factors in human proliferative sickle cell retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:838–46. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.7.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao G, Li Y, Zhang D, et al. Unbalanced expression of VEGF and PEDF in ischemia-induced retinal neovascularization. FEBS Lett. 2001;489:270–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blair NP, Goldberg MF, Fishman GA, Salzano T. Autosomal dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy (ADVIRC) Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68(1):2–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi K, Itagaki T, Yamagishi K, et al. A role of the retinal pigment epithelium in the involution of subretinal neovascularization. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1990;94(4):340–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller H, Miller B, Ryan SJ. The role of retinal pigment epithelium in the involution of subretinal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27(11):1644–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glaser BM, Campochiaro PA, Davis JLJ, Sato M. Retinal pigment epithelial cells release an inhibitor of neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:1870–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050120104029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]