Abstract

Objectives

To describe the paediatric transgender population accessing health care through the Manitoba Gender Dysphoria Assessment and Action for Youth (GDAAY) program, and report youth’s experiences accessing health care in Manitoba.

Methods

Demographic, medical, surgical and mental health information was extracted from the medical records of youth referred to the GDAAY program (n=174). A 77-item online survey was conducted with a subset of those youth (n=25) to identify common health care experiences and perceptions of trans youth in Manitoba.

Results

Chart review of 122 natal females and 52 natal males, ranging in age from 4.7 to 17.8 years (mean 13.9 years), found 66 patients (46.8%) with a pre-existing or current mental health diagnosis, of which anxiety and depression were the most common (n=43, 30.5%). Qualitative self-reports revealed all patients had negative interactions with health care providers at some point, many having experienced lack of engagement with the medical system due to reported lack of knowledge by the provider on trans-related health services.

Conclusion

Transgender youth in Manitoba seeking GDAAY services have high rates of anxiety and depression. These youth face adversity in health care settings and are distressed over long wait times for mental health services. Recommendations to improve care include increasing general health care providers’ education on gender affirmative care, providing gender sensitivity training for health care providers, gathering preferred names and pronouns during triage, increasing visibility of support for LGBT+ persons in clinics, increasing resource allocation to this field and creating policies so all health care settings are safe places for trans youth.

Keywords: Adolescent, Endocrinology, Gender Dysphoria, Health Services for Transgender Persons, Mental Health, Pediatrics

Gender dysphoria (GD), the distress caused by a difference between one’s gender identity and natal sex, has an estimated prevalence of 0.005% to 0.014% in natal males and 0.002% to 0.003% in natal females with the incidence increasing in recent years (1–3). Trans is an umbrella term that includes a wide spectrum of identities, including transgender individuals who seek transition from one natal sex to the other (4). The term trans is used in this study to be inclusive of all youth referred to the GDAAY program.

Developing a gender identity is an aspect of normative child development with most children developing a cisgender identity, where natal sex is in keeping with their gender identity and expression (1). Gender identity exists on a spectrum, including masculine, feminine, aspects of both (gender queer) or neither (agender) (1). The mental health of trans children often suffers when gender norms and messaging based on natal sex are not congruent with who they perceive themselves to be. This likely plays a role in the high rate of attempted suicide in this population (1,5,6). Studies report higher rates of anxiety, depression and self-harm in the trans population compared with cisgender youth (7,8). Studies show that increased social inclusion, reduced transphobia and access to medical transition can reduce the risk of suicide ideation and attempts (7,9,10). Unfortunately, many trans individuals avoid the health care system based on fear of discrimination, or previous negative experiences (9,11,12).

Since its inception in 2011, the Gender Dysphoria Assessment and Action for Youth (GDAAY) program has provided Manitoba’s trans youth with access to trans-specific health care. The program is composed of a paediatric endocrinologist, a paediatric endocrine nurse, a paediatric clinical health psychologist, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and an adolescent gynecologist. Prior to GDAAY, those under 18 years old in need of trans-specific health care had no comprehensive paediatric program to access these services.

There are limited data published regarding health programming for trans youth and their health care experiences (13, 14). The aim of this study was to describe the GDAAY program’s patient population and explore their health care experiences in Manitoba.

METHODS

Chart review

All GDAAY charts were reviewed for demographic information including age, natal sex, ethnicity, city/town of residence and Child and Family Services (CFS) involvement. Date of referral, first endocrine or mental health appointment, medical interventions, any mental health diagnosis, surgical interventions and reasons for discharge were also extracted. Referrals that were redirected and not followed by GDAAY were only included in the number and demographics of referrals.

Chart data coding

Wait times were determined from date of referral and first contact with the endocrinologist, psychologist or psychiatrist. Active patients were derived from the number of referrals minus the number of patients discharged per year. Medical intervention was coded for reversible medical intervention (Leuprolide acetate/Lupron Depot or Medroxyprogesterone acetate/Depo-Provera) and partially reversible cross-sex hormone therapy. Any mental health diagnosis was gathered but analysis focused on only depression and anxiety disorders.

Survey

A 77-item Internet-based survey over the period of August 2015 to July 2016 was conducted. Questions were adapted from previously validated surveys to obtain personal experiences with health care services provided to trans youth in Manitoba (4,15,16). The survey was anonymous and took 20 to 40 minutes to complete. Where necessary, we encouraged parent/guardian assistance to help patients answer all survey questions. GDAAY patients were notified of the survey via email and/or through recruitment posters. Patients no longer wanting trans services (n=20), whose referrals were redirected (n=33) and those lost to follow-up (n=12) were not contacted for survey participation.

Data analysis

Chi-Square and Fisher’s Exact Tests were used to analyze the data. Wilcoxon scores were used when there were continuous variables with average scores being used for ties. The rank score sums from the Wilcoxon tests were then analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance test. A P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Chart review identified 174 charts. Thirteen patient charts had only referral information as the youth exceeded the age limit to be followed by GDAAY and were redirected to adult services. Values for n vary due to patient age- and sex-based eligibility for treatments. Ninety-six patients were eligible and contacted for the survey, of which 25 responded (26%). A description of the population derived from chart review and the mental health analysis is found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chart review for demographics and analysis of patient mental health diagnosis, specifically anxiety or depression

| All patients | Any mental health diagnosis | No mental health diagnosis | P value | Anxiety/depression diagnosis | No anxiety/depression diagnosis | P value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or mean | Total n | n (%) or mean | Total n | n (%) or mean | Total n | n (%) or mean | Total n | n (%) or mean | Total n | ||||

| Average Age at Referral | 13.9 | 174 | 14.4 | 66 | 13.5 | 108 | 0.23 | 14.9 | 49 | 13.5 | 112 | 0.04 | |

| Natal Sex | 174 | 66 | 108 | 0.20 | 49 | 125 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Natal Male | 52 (30) | 16 (9) | 36 (21) | 8 (5) | 44 (25) | ||||||||

| Natal Female | 122 (70) | 50 (29) | 72 (41) | 41 (24) | 81 (47) | ||||||||

| Ethnicity | 161 | 66 | 95 | 0.10 | 49 | 112 | 0.86 | ||||||

| First Nation | 38 (26) | 20 (12) | 18 (11) | 12 (7) | 26 (16) | ||||||||

| Non-First Nation | 123 (76) | 46 (29) | 77 (48) | 37 (23) | 86 (53) | ||||||||

| Home location | 161 | 66 | 95 | 0.66 | 49 | 112 | 0.59 | ||||||

| Winnipeg | 116 (72) | 49 (30) | 67 (43) | 36 (22) | 80 (50) | ||||||||

| Rural Manitoba | 34 (21) | 12 (7) | 22 (14) | 10 (6) | 24 (15) | ||||||||

| First Nation Reserve | 7 (4) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | ||||||||

| Out of Province | 4 (2) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2) | ||||||||

| CFS | 161 | 64 | 94 | 0.06 | 47 | 111 | 0.86 | ||||||

| CFS involvement | 35 (22) | 19 (12) | 16 (10) | 10 (6) | 25 (16) | ||||||||

| No CFS Involvement | 126 (78) | 45 (28) | 78 (49) | 37 (23) | 86 (54) | ||||||||

CFS Child and Family Services

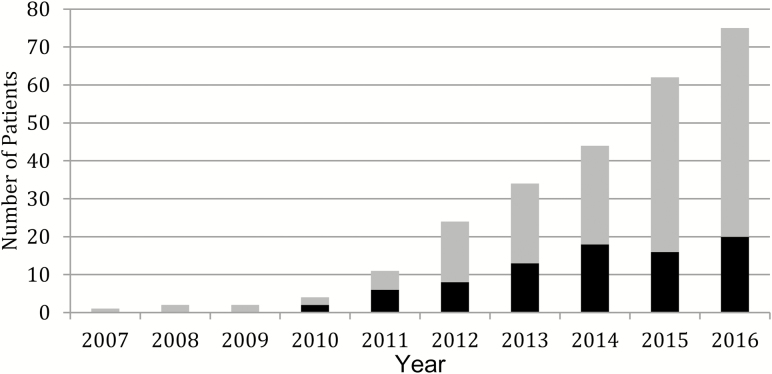

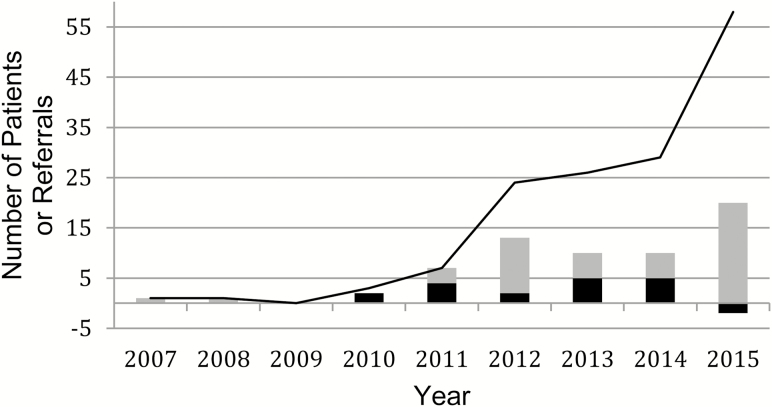

Since inception, rates of referrals to GDAAY has tripled (Figure 1), with the referrals far exceeding the new consultations seen by GDAAY each year (Figure 2). Based on limited program capacity and wait times, 33 referrals were redirected for youth age 16 to 18 to adult care.

Figure 1.

Number of active patients in the Manitoba Gender Dysphoria Assessment and Action for Youth program from 2007 up to July 1, 2016. Grey bar represents natal female patients; black bar represents natal male patients.

Figure 2.

Number of new natal male and natal female patients actively being seen by the Manitoba Gender Dysphoria Assessment and Action for Youth (GDAAY) and total number of new referrals to GDAAY program from 2007 to 2015. Grey bars represent the new natal female patients; black bars represent new natal male patients; Black line represents the number of referrals GDAAY received over that year. Two more natal male patients were discharged than were accepted into the GDAAY program in 2015, accounting for the negative value for this year.

Comparison of youth who completed the survey with the larger GDAAY population (based on data from chart reviews) found no significant differences in age, natal sex, ethnicity, living location, rate of cross-sex hormone therapy, surgical intervention or mental health diagnosis. The only significant difference between these groups was that the survey group had a higher proportion of patients on reversible medical therapy (P=0.01).

Transition in our population

Survey respondents reported becoming aware of their transgender identity on average around 8.7 years old but did not receive trans-related health care until an average of 13.3 years. Respondents first disclosed their trans status to their family doctor (17%, n=4), psychologist (25%, n=6), nurse (8%, n=2), social worker or counselor (25%, n=6), support group (4%, n=1), family or friends (17%, n=4) or paediatric subspecialist (4%, n=1). At an average age of 12.5 years, 21 survey respondents (88%) are presenting publically in their desired gender. Most respondents (96%, n=23) have asked people to start calling them by a name and pronoun that reflects their gender identity, but only 38% (n=9) have legally changed their name.

The average age patients started taking Leuprolide acetate, or Medroxy progesterone acetate, was 13.2 years old (n=21, 18%), and 16.1 years old (n=22, 27%), respectively. Cross hormone therapy was started on average at16.6 years old (n=29, 48%). Percentage of participants prescribed Leuprolide acetate, Medroxyprogesterone acetate or cross hormone therapy was derived from eligible cases and excluded patients too young for intake into GDAAY (n=2) or under 15 years of age for cross hormone therapy (n=72), those not seen by GDAAY (n=33), those no longer wanting to transition (n=20) and natal males (for Medroxyprogesterone acetate). Prior to starting Leuprolide acetate patients were assessed by the paediatric endocrinologist to be at least Tanner Stage 2. This is to ensure children are physiologically capable of pubertal progression. Patients on Medroxyprogesterone acetate were Tanner stage 5. Natal female patients were more likely to be taking cross-sex hormones (P=0.047) than natal male patients. Fourteen natal female patients (37%) have had bilateral mastectomies.

Health care experiences with primary care providers

Of the 20 participants who responded regarding health care experiences, 70% (n=14) reported having to provide some education to a health care provider regarding their needs as a trans patient, 15% (n=3) felt they had been denied equal treatment and avoid emergency medical care because of their trans identity. Identifying specific experiences of discrimination by health care providers, 25% (n=5) reported experiencing hurtful/insulting language about their trans identity, 15% (n=3) were discouraged from asking trans-related health questions, 20% (n=4) were told they were not trans, 10% (n=2) were discouraged from exploring their gender, 35% (n=7) felt belittled for their trans identity and 15% (n=3) reported the health care provider refusing to use their preferred name. Thirteen patients (65%) were told that the provider did not know enough about trans-related care to provide it. These experiences may result in avoidance of medical care by the trans community as described in the following quote:

“I feel some anxiety around the health care system but I believe that doctors should be aware of transgender people and I shouldn’t be shamed of asking questions regarding me being transgender and how that affects my general health.”

Regarding barriers to accessing health care, 68% (n=13) reported that medical information collected prior to seeing a doctor is very male/female centered, 68% (n=13) reported no evidence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and other gender and sexual minority (LGBT+) support in clinics, 74% (n=14) worry about embarrassing transition questions, 68% (n=13) worry about sexual orientation questions, 63% (n=12) perceived a lack of health care provider education regarding LGBT+ people, 84% (n=16) worry about improper pronouns being used and 32% (n=6) worry about being laughed at or belittled.

Access to GDAAY services

Average wait times to see any GDAAY team member was 114 days. From the chart review, we found that ethnicity and home location did not affect wait times and access to interventions. Some survey respondents expressed discontent with wait times, exemplified by the following comments:

“It takes too long of a time to see a psychiatrist or psychologist, and way too long of a wait for the gender to be able to be changed on the birth certificate. My TransMale identity makes me uncomfortable enough, let alone seeing my female birth name on everything.”

“Relating to GDAAY, I have been waiting over a year to see a psychologist to start hormone therapy. It’s been stressful and frustrating.”

Mental health

Chart review found that over one-third of patients (38%, n=66) in the GDAAY program have a diagnosed mental health disorder with anxiety and depression being the most common. A diagnosis of anxiety or depression was more likely in natal females and in patients referred at an older age. Self-harm behaviours are also common in the patient population (21%, n=36). There were four patients with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis with two more patients having ASD traits not formally meeting diagnostic criteria.

From 22 respondents, 64% (n=14) rated their own mental health as either poor or fair and 27% (n=6) said they were either unhappy or very unhappy with their life in general. Over one-half (55%, n=14) reported feeling depressed more than 3 to 4 days in the past week and 64% (n=14) reported feeling happy less than 2 days in the past week. Another 64% (n=14) of survey respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement, “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.”

DISCUSSION

Transition in our population

The average of 4.5 years between gender questioning and receiving care may partly be explained by the coming out process. With increasing social acceptance of trans people, this gap may shorten in the future. Hopefully by reducing transphobia, trans youth are able to feel safer disclosing their trans status, and they can begin accessing transition services earlier.

Health care experiences with primary care providers

Barriers identified in the survey include very male- or female-centered approaches to collecting health information, lack of LGBT+ support in clinics, worry regarding being embarrassed, made fun of, or belittled due to questions about sexual orientation or trans identity, perceived lack of care provider education regarding trans health needs and improper pronoun and preferred name usage. Many barriers can be reduced to make health care settings more open to trans people. When collecting information prior to seeing a doctor, for example, leaving a blank space to fill out for gender can help affirm trans identities. Support can be shown by having welcoming (often represented by the rainbow) stickers, posters and information for all sexual and gender minorities. Making health care settings more affirming to trans identities, such as gender-neutral bathrooms in clinics, can help minimize barriers to access improve health care utilization in the future, especially in the adolescent population (17).

Access to GDAAY services

As the discrepancy between referrals and first clinical visit into GDAAY grows (Figure 2), wait times for services are expected to increase. These long wait times may explain that while 96% (n=23) of survey respondents have chosen a gender affirming name and pronouns, only 38% (n=9) of respondents legally changed their names. Along with legally changing names, correcting the gender marker on legal documentation is important for these patients. In Manitoba changing the sex on one’s birth certificate requires a letter from a Canadian medical practitioner, nurse practitioner, psychologist or psychological associate supporting this change is required (18). Any health care provider could provide this letter, but youth and their families may not know this until the first clinical visit, which is an average of 114 days from the referral. This may be leaving patients distressed over incorrect legal documentation for much longer than is necessary.

Mental health

Mental health assessments prior to starting medical intervention are completed to confirm a GD diagnosis, ensure stability of the GD/gender nonconformity and ensure any comorbid mental health concerns that could interfere with treatment are diagnosed and addressed. These criteria, set by World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), are to be met prior to receiving puberty suppressing hormones (19). Patients who are older at referral to GDAAY are more likely to have diagnosed anxiety or depression, which may be due to older teens in general having higher rates of anxiety and depression (20).

Limitations

There are inherent limitations to retrospective chart review. Anxiety and depression diagnoses were derived from mental health history in the chart and therefore it is not possible to standardize diagnostic criteria. There is also a difference between chart documentation of a diagnosis of major depressive disorder and experiences of depressive symptoms derived from the survey. Many patients have symptoms of depression but do not meet diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. There is also a potential for recall bias with patients focusing on negative experiences.

While our survey responses were limited in number, the respondents did not significantly differ in demographics from our overall GDAAY population outside of reversible medical intervention rates. However, we acknowledge that these respondents may differ from the general GDAAY population in ways we did not measure.

CONCLUSION

Our research supports the need for ongoing discourse regarding trans health care services in Manitoba. Through examination of our program’s growth, population and feedback from our trans youth we have derived a series of recommendations. We recommend:

Education regarding gender affirmative care is included in curricula for all health care professionals.

All staff working in a medical facility attend gender sensitivity training regarding how to be respectful of patients who may not identify as cisgender.

Increasing resource allocation to the treatment of trans youth in Manitoba.

Changing the protocol for collecting patient information to include preferred names and pronouns and make these available on electronic records.

Enhancing visibility of support for LGBT+ persons in clinics.

Creating health policies to address trans people’s rights regarding the correction of gender markers and names on health forms and antidiscrimination guidelines.

While there have been recent improvements in the care of Manitoba’s trans youth with the introduction of the GDAAY program, there are still areas of improvement needed. This article highlights the adversity trans youth face in primary health care settings and identifies deficiencies in the current system. By improving health care experiences for trans youth, they may have a more positive outlook about health care providers and be more likely to seek health care when needed in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the youth and their parents/guardians who participated in the study, Dr. Elizabeth Sellers for critical review of the manuscript and Dr. Michelle Xiao-Qing Liu for her assistance with statistical analysis and interpretation.

Ethics Approval granted by The University of Manitoba Bannatyne Campus Health Research Ethics Board and the Health Sciences Centre Pediatric Research Coordinating Committee

References

- 1. Bonifacio HJ, Rosenthal SM. Gender variance and dysphoria in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am 2015;62(4):1001–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zucker KJ, Lawrence A. Epidemiology of gender identity disorder: Recommendations for the standards of care of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Int J Transgenderism. 2009;11(1):8–18. [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association publishing, 2013:991. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor C, Peter T. Every class in every school: Final report on the first national climate survey on homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia in Canadian schools. 2011;1–152.

- 5. Carver PR, Yunger JL, Perry DG. Gender identity and adjustment in middle childhood. Sex Roles. 2003;49(3–4):95–109. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Costa PA, Davies M. Portuguese adolescents’ attitudes toward sexual minorities: Transphobia, homophobia, and gender role beliefs. J Homosex 2012;59(10):1424–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Budge SL, Adelson JL, Howard KA. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81(3):545–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Claes L, Bouman WP, Witcomb G, Thurston M, Fernandez-Aranda F, Arcelus J. Non-suicidal self-injury in trans people: Associations with psychological symptoms, victimization, interpersonal functioning, and perceived social support. J Sex Med 2015;12(1):168–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Pyne J, Travers R, Hammond R. Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 2015;15:525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Denny S, Lucassen MF, Stuart J et al. The association between supportive high school environments and depressive symptoms and suicidality among sexual minority students. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2016;45(3):248–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bradford J, Reisner SL, Honnold JA, Xavier J. Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the virginia transgender health initiative study. Am J Public Health 2013;103(10):1820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kosenko K, Rintamaki L, Raney S, Maness K. Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Med Care 2013;51(9):819–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bauer GR, Scheim AI, Deutsch MB, Massarella C. Reported emergency department avoidance, use, and experiences of transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. Ann Emerg Med 2014;63(6):713–20.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Testa RJ, Sciacca LM, Wang F et al. Effects of violence on transgender people. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2012;43(5):452–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scheim AI, Bauer GR. Sex and gender diversity among transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. J Sex Res 2015;52(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grant J, Mottet L, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman J, Keisling M.. Injustice at Every Turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bauer GR, Hammond R, Travers R, Kaay M, Hohenadel KM, Boyce M. “I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2009;20(5):348–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. The legislative assembly of Manitoba. Bill 56: The Vital Statistics Amendment Act. Manitoba, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M et al. Standards of care, for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people. Int J Tansgenderism. 2012;13(4):165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: Developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2009;32(3):483–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]