Abstract

The first phase of molecular brain imaging of microglial activation in neuroinflammatory conditions began some 20 years ago with the introduction of [11C]-(R)-PK11195, the prototype isoquinoline ligand for translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO). Investigations by positron emission tomography (PET) revealed microgliosis in numerous brain diseases, despite the rather low specific binding signal imparted by [11C]-(R)-PK11195. There has since been enormous expansion of the repertoire of TSPO tracers, many with higher specific binding, albeit complicated by allelic dependence of the affinity. However, the specificity of TSPO PET for revealing microglial activation not been fully established, and it has been difficult to judge the relative merits of the competing tracers and analysis methods with respect to their sensitivity for detecting microglial activation. We therefore present a systematic comparison of 13 TSPO PET and single photon computed tomography (SPECT) tracers belonging to five structural classes, each of which has been investigated by compartmental analysis in healthy human brain relative to a metabolite-corrected arterial input. We emphasize the need to establish the non-displaceable binding component for each ligand and conclude with five recommendations for a standard approach to define the cellular distribution of TSPO signals, and to characterize the properties of candidate TSPO tracers.

Keywords: Translocator protein, positron emission tomography, quantitation, neuroinflammation, microglia

Introduction

The translocator protein (18 kDa) (TSPO), formerly known as the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR), is a five-membrane domain protein expressed in mitochondria of a diverse range of cell types present in peripheral tissues and the central nervous system. Based on the observation that microglia, which are the resident macrophages of the brain, express the TSPO de novo upon activation by a broad range of pathological stimuli, the TSPO binding site has emerged as an important target for molecular imaging by positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Indeed, the rate of publications on TSPO imaging has been undergoing a phase of exponential growth, with approximately two new articles appearing every week in 2017. This burgeoning interest reflects innovations in tracer development, as well as the growing appreciation of the importance of inflammation in brain pathologies. However, important aspects of the neurobiology of TSPO, including its specificity for microglia, remain unelucidated. In addition, the proper quantitation of the TSPO PET signal presents certain difficulties, a problem compounded by the plethora of competing tracers that have become available in the past five years. The purpose of this review is to draw attention to some neglected aspects of TSPO neurobiology, and to discuss systematically the various approaches applied for TSPO quantitation, based upon literature reports for a series of 13 tracers characterized in human PET studies.

Microglial activation occurs in diseases of fundamentally different aetiologies, now commonly subsumed under the term neuroinflammation, although this concept may be somewhat ill-defined.1–4 Neuroinflammation is often considered synonymous with microglial activation, irrespective of any categorical differences in the expressed transcriptome of different inflammatory disease conditions.5 However, astroglial reactions and infiltration of immunologically active cells, such as CD4+ T cells arising from the periphery,6 may also contribute to inflammatory reactions and TSPO binding in the brain. Small increases in the PET signal from TSPO ligands, assuming high process specificity of the analysis,7 may in some circumstances be attributable to perivascular cells.8 Thus, neuroinflammation is per se a complex process involving various cells type and the activation of intercellular communication pathways not universally linked to TSPO expression de novo in activated microglia.8,9 Due to the imperfect specificity of TSPO as a microglial marker, any finding of increased cerebral TSPO expression properly constitutes a generic measure of disease pathology or progression. For example, axotomy in the rat hippocampus was followed by synchronous increases in TSPO binding sites to autoradiography, along with parallel increases in the mRNA for TSPO and the microglial marker CD11b, indicating a close affiliation between TSPO and microgliosis in that lesion model.10 On the other hand, the very rapid increases in TSPO signal observed after challenge with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS11) seem more consistent with infiltration of monocytes or other blood cells into the brain parenchyma, rather than microgliosis. Furthermore, increased TSPO binding in a rodent neuroinflammation model has been linked to elevated expression in reactive astrocytes, with no such increase in microglia.12 Thus, the attribution of TSPO PET signals specifically to microglial activation must be established for each disease model and condition, and may change as a function of time.

As a measure of the importance now attributed to the concept of TSPO expression as a marker of neuroinflammation, TSPO PET has attracted considerable attention, despite the caveats noted above. PET studies have investigated TSPO in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia,13,14 multiple sclerosis,15 ischemic stroke,15–18 epilepsy,19 herpes virus infection,20 traumatic brain injury,21 major depression,22 bipolar disorder23 and schizophrenia.7,24–27 As we shall see below, the findings in schizophrenia remain contentious, and the disparate results may exemplify the need to adopt standard procedures for analysis. In addition to revealing neuroinflammation, TSPO PET can monitor trans-synaptic activation of microglia in relation to physiological neuroplasticity and synaptic remodeling.28,29 Indeed, preclinical studies with minocycline, an inhibitor of microglial activation, indicate an essential role for microglia in neurogenesis and synaptic pruning in the immature brain, possibly standing in contrast to deleterious effects of microglial activation in inflammation of the adult brain.30 On the other hand, TSPO expression is altered by exposure to ionizing radiation,31 suggesting an involvement of microglial activation in the sequelae of radiotherapy. Overall, TSPO expression is now considered a diagnostic biomarker and a therapeutic target for a broad range of inflammatory, neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders (as reviewed by Liu et al.3).

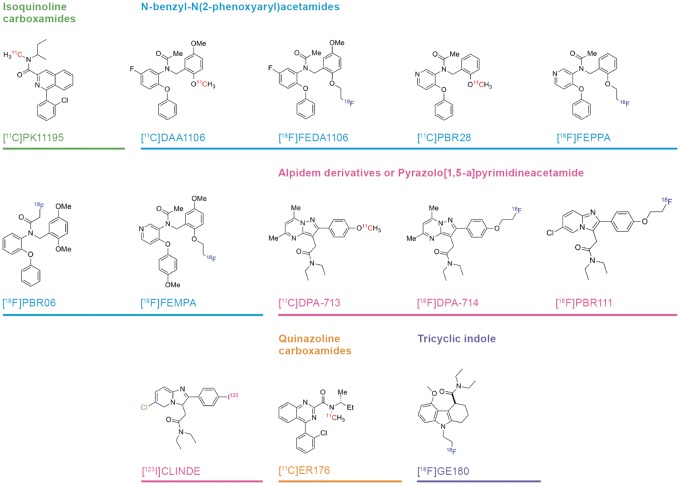

The first phase of TSPO PET research was driven by the prototype isoquinoline ligand [11C]-(R)-PK11195, which revealed microglial activation in patients suffering from glioma,32 Rasmussen’s encephalitis,33 stroke16 and multiple sclerosis.15 The pharmacological selectivity of (R)-PK11195 as well as that of the second-generation ligand PBR111 has been confirmed in TSPO knock-out animals.9 However, [11C]-(R)-PK11195 PET shows relatively low specific signal even in the clinical conditions noted above, where microglial activation is often a prominent and well-established feature. This limitation motivated a concerted search for PET ligands with higher specific binding in living brain. The next phase of TSPO PET research was heralded by the development of [11C]PBR2834 and other second generation ligands, now numbering in the dozens, and belonging to at least five structural classes (Figure 1). As shall be seen, many of the new TSPO ligands impart manifestly higher in vivo binding signals in normal and diseased brain as compared to [11C]-(R)-PK11195.

Figure 1.

Structures and structural classes of 13 TSPO PET or SPECT tracers investigated by compartmental analysis. PET: positron emission tomography; SPECT: single photon emission computed tomography; TSPO: translocator protein.

Despite this progress in PET tracer development, several key issues related to TSPO quantitation remain to be resolved. In particular, the TSPO PET signals measured in healthy young subjects reveal constitutive TSPO protein expression throughout brain, such that there is no perfectly valid non-binding reference region for calculating the specific binding in regions of interest. Consequently, there are ground for undertaking quantitative analysis of TSPO ligand uptake relative to a metabolite-corrected arterial input function. In this circumstance, which entails considerable logistic and technical difficulties, as well as discomfort for the subject, the endpoint for TSPO PET quantitation is the total distribution volume for the tracer (VT; ml g−1), which is the composite of specific binding (VS) and non-specific or non-displaceable binding (VND). Increases in the magnitude of VT reveal microgliosis, but the relative proportions of VS and VND are difficult to ascertain experimentally, in the absence of a non-binding reference region where the entire equilibrium binding is due to VND alone. In addition, there is no general agreement if VT quantitation should properly entail correction for the free fraction of tracer in plasma. Finally, the aberrantly low TSPO binding in some humans individuals, first described for [11C]PBR28,34 is now understood to reflect a functional polymorphism of the TSPO gene with respect to binding of many of the newer ligands. The allelic abundance in humans is approximately 5:2 in favour of the high affinity binding allele (HAB),35 such that 10% of humans will show little or no TSPO specific binding, and approximately 40% will show intermediate binding. The design of most PET studies using the available TSPO ligands accommodates this phenomenon, although the prototypic tracer [11C]-(R)-PK11195 is indifferent to allelic status.

In our systematic literature review, we have identified 13 TSPO ligands belonging to five structural classes (Figure 1), each of which has been characterized with respect to binding in healthy human brain using compartmental analysis relative to a metabolite-corrected arterial input (Table 1) and for binding affinity and metabolite profile (Table 2). We intend our compilation to help identify which among the available tracers are best suited for human PET studies, based on the criterion of high specific binding relative to the nonspecific background. By considering this and other criteria, we aim to define a framework for systematic comparison of multiple candidates for this molecular target, and by extension for the general problem of tracer optimization. In other words, what information is necessary to inform a rational decision between candidate radiotracers? To develop this framework, we first present a brief history of the biochemistry and pharmacology, and evolutionary biology of the TSPO site. We then present an account of the functional properties attributed to TSPO, followed by a review of the cellular distribution of TSPO expression, and some details on the natural abundance of the site in normal brain tissue. We devote the main part of the review to the comparative approaches for quantitation of TSPO binding, ranging from simple uptake measurements to complex compartmental analysis. Here, we give special consideration to the issue of allelic dependence of the binding of most TSPO PET ligands. We next discuss matters related to plasma protein binding and metabolism of PET tracers, and conclude our review with five suggestions towards adoption of standard criteria for judging the relative merits of TSPO tracers.

Table 1.

Compartmental analysis of binding of 13 TSPO ligands in brain in relation to allelic status.a

| Tracer | N | K1 (ml g−1 min−1) | VND (K1/k2; ml g−1) | BPND (k3/k4) | VT (ml g−1) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11C]-(R)-PK11195 | 13 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | Large forebrain volume, not genotyped. Kropholler et al.109 |

| 6 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 1.6 ± 0.4 | 0.69 ± 0.17 | Whole grey matter, not genotyped. Jucaite et al.128 | |

| 3 (LAB) 8 (MAB) 5 (HAB) | 0.42 0.42 0.42 | 0.5 0.9 0.8 | 0.60 ± 0.18 0.74 ± 0.16 0.74 ± 0.14 | Whole brain, common VND calculated by Lassen plot. Kobayashi et al.124 | ||

| [11C]DAA1106 | 9 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | Not genotyped. Ikoma et al.143 |

| [18F]FEDA1106 | 7 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 15.4 ± 4.0 | Not genotyped. Fujimura et al.132 |

| [11C]PBR28 | 1 | 0.86 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 160 | Putamen in rhesus monkey. Imaizumi et al.93 |

| 3 | 14.3 | 3.5 | 63 ± 18 (2TCM) | Rhesus monkey, common VND estimated from Lassen plot. Mitsui et al.122 | ||

| 12 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 1.10 ± 0.04 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | Caudate, not genotyped. Fujita et al.112 | |

| 3 (MAB) 3 (HAB) | 0.9 0.9 | 2.7 5.1 | 2.6 ± 1.1 4.3 ± 1.8 | Cortical grey matter. VND and BPND assume no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Collste et al.129 | ||

| 10 (MAB) 16 (HAB) 10 (MAB) 16 (HAB) | 1.55 1.55 2.0 2.0 | 0.9 1.8 0.47 1.2 | 2.9 ± 0.3 4.3 ± 0.3 | Cortical grey matter. VND and BPND assuming (upper) no contribution of non-binding allele to VT and (lower) from Lassen plot. Owen et al.144 | ||

| [18F]FEPPA | 12 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 1.7 | 11.8 ± 3.1 | Not genotyped. Rusjan et al.131 |

| 6 (MAB) 13 (HAB) | 5 5 | 0.6 1.2 | 8 11 | Common VND assumes no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Mizrahi et al.116 | ||

| [18F]PBR06 | 7 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.08 | 5.0 ± 2.4 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | No genotyping. Fujimura et al.132 |

| [18F]FEMPA | 3 (MAB) 4 (HAB) | 0.57 0.57 | 1.1 2.2 | 1.17 ± 0.46 1.85 ± 0.12 | VND and BPND assuming no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Varrone et al.145 | |

| [11C]DPA-713 | 5 | 0.27 ± 0.05 (1TCM) | 4.11 ± 0.84 (1TCM) | Not genoytyped. Endres et al.146 | ||

| 5 (MAB) 9 (HAB) | 0.3 0.3 | 6 14 | 2.2 ± 0.3 4.1 ± 1.1 | Common VND assumes no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Coughlin et al.147 | ||

| 3 (LAB) 5 (MAB) 14 (HAB) | 0.44 0.44 0.44 | 1.8 3.4 7.3 | 1.21 ± 0.15 1.94 ± 0.17 3.61 ± 0.56 | Whole brain, common VD from Lassen plot. Kobayashi et al.124 | ||

| [18F]DPA-714 | 6 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | Not genotyped. Golla et al.148 |

| 3 (MAB) 7 (HAB) 3 (MAB) 7 (HAB) | 0.40 ± 0.08 0.31 ± 0.17 | 0.46 ± 0.20 1.2 ± 0.9 1.4 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.1 2.8 ± 1.3 1 2 | 2.8 ± 0.3 4.2 ± 2.3 | Quantified by 2TCM (upper), or using common VD from graphical analysis of HAB and MAB VT data (lower), assuming no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Lavisse et al.12 | |

| [18F]PBR111 | 4 (LAB) 8 (MAB) 9 (HAB) 4 (LAB) 8 (MAB) 9 (HAB) | 0.27 ± 0.04 0.24 ± 0.02 0.29 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.2 1.2 ± 0.2 2.1 ± 0.8 0.93 0.93 0.93 | 1.0 ± 0.5 1.0 ± 0.5 2.0 ± 1.0 1.4 1.9 3.3 | 2.22 ± 0.57 2.71 ± 0.48 4.03 ± 1.30 | Cortical grey matter, quantified by 2TCM (upper), or using common VND from graphical analysis of HAB and MAB VT data (lower), assuming no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Guo et al.127. |

| [123I]CLINDE | 4 (MAB) 5 (HAB) 5 (MAB) 3 (HAB) | 0.23 ± 0.06 0.27 ± 0.06 | 1.3 ± 0.4 1.9 ± 0.7 1.2 1.2 | 1.2 ± 0.5 2.2 ± 0.5 1.9 3.8 | 3.5 ± 0.8 5.8 ± 0.7 | Cerebral cortex quantified by 2TCM (Dr Ling Feng, personal communication), and common VND from graphical analysis of HAB and MAB VT data (lower), assuming no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Feng et al.97 |

| [11C]ER176 | 2 (LAB) 3 (MAB) 3 (HAB) | 0.65 0.65 0.65 | 1.5 3.5 4.4 | 1.6 ± 0.5 2.9 ± 1.0 3.5 ± 0.9 | Grey matter. Common VD estimated from the Lassen plot. Ikawa et al.126 | |

| [18F]GE180 | 5 (MAB) 5 (HAB) | 0.0102 | 0.053 | 4.6 | 0.27 ± 0.08 0.28 ± 0.10 (Logan) | 2TCM results for pooled HAB and MAB groups, mean VT results reported separately. Feeney et al.139 |

| 4 (MAB) 6 (HAB) | 0.50 0.50 | 1.0 2.0 | 0.10 ± 0.04 0.15 ± 0.06 | VND and BPND from graphical analysis of HAB and MAB data assuming no contribution of non-binding allele to VT. Fan et al.138 |

LAB: low affinity binders; MAB: mixed affinity binders; HAB: high affinity binders.

The analysed brain region was frontal cortex in healthy humans (except where noted). Compartmental analysis was made using a two-tissue compartment model (2TCM) for estimation of the unidirectional blood–brain clearance (K1), the apparent non-displaceable binding (VND; K1/k2), and binding potential (BPND; k3/k4); where noted, the compartmental analysis was made using a one tissue compartment model (1TCM). The total distribution volume (VT) was calculated by the Logan analysis, relative to a metabolite-corrected arterial input function. Where noted, VD and BPND were also estimated using a population mean VND obtained by blocking studies (i.e. Lassen method) or using an algebraic/graphical analysis of VT as a function of allelic status. Each result is reported as the mean (±SD) of N determinations, except for the case of population-based estimates.

Table 2.

Summary of binding affinity and plasma metabolism for 13 TSPO ligands.a

| Tracer | Affinity | % unmetabolized parent | Plasma metabolite Retention factors (Rf) | Plasma free fraction (fp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11C]PK11195 | KD of [3H]-R-PK11195 in rat brain tissue: 7 nM. Venneti et al.149 KD of [3H]PK11195 in human brain tissue 29 nM (HAB) 31 nM (LAB). Owen et al.83 | 80% at 10 min 50% at 60 min Endres et al.146 | At 20 min p.i. in humans: 10% M1 at Rf 0.0, 10% M2 at Rf 1.5, 80% parent eluting at Rf 4.0 De Vos et al.150 | 0.066 Owen et al.113 0.01 Endres et al.146 |

| [11C]DAA1106 | KD [3H]DAA1106 for rat brain mitochondrial fraction: 0.12 nM Chaki et al.151 KD [3H]DAA1106 in rat brain tissue: 0.4 nM. Venneti et al.149 Ki against [3H]PK11195 in human brain tissue: 3 nM (HAB) 13 nM (LAB) Ki in rat mitochondrial fraction: 0.043 nM Ki in monkey mitochondrial fraction: 0.19 nM Owen et al.113 | 90% at 10 min 25% at 60 min Ikoma et al.143 | Rf of plasma metabolites not reported, but main metabolite in monkey reported to be DAA1123 Maeda et al.121 | Not reported |

| [18F]FEDAA1106 | IC50 relative to [11C]DAA1106 binding in rat brain: 0.8 nM, i.e. two-fold higher than DAA1106 Zhang et al.152 | 80% at 10 min 20% at 60 min Varrone et al.118 | Rf of plasma metabolites not reported. | Not reported |

| [11C]PBR28 | KD of [3H]PBR28 in human brain tissue according to two-site model: 1.3 nM and 135 nM. Owen et al.83 Ki against [3H]PK11195 in human brain tissue: 2.9 nM (HAB) 237 nM (LAB) Owen et al.113 | 60% at 10 min 9% at 60 min Hannestad et al.153 | Rf of plasma metabolites not reported. | 0.03 (HAB) 0.05 (LAB) Owen et al.83 0.11 Collste et al.129 |

| [18F]FEPPA | Ki against [3H]PK11195 in rat mitochondrial fraction: 0.07 nM. Wilson et al.119 | 70% at 10 min 10% at 60 min Rusjan et al.131 | At 60 min p.i.: 40% at Rf = 0, 5% at Rf = 3 35% at Rf = 4 10% parent at Rf = 6. Rusjan et al.131 | Not reported |

| [18F]PBR06 | Ki against [3H]PK11195 in human brain tissue: 9 nM (HAB) 149 nM (LAB). Owen et al.113 | 45% at 10 min 18% at 60 min Fujimura et al.132 | At 30 min p.i. 47% at Rf = 0 16% at Rf = 1.3 37% parent at Rf = 2. Fujimura et al.132 | 0.02 Fujimura et al.132 |

| [18F]FEMPA | Ki against against [3H]PK11195 in human phagocyte mitochondrial fraction: 3.7 nM (allelic status not specified, Piramel Brochure) | 35% at 10 min 8% at 60 min. Varrone et al.118 | At 60 min p.i. 45% at Rf = 0 35% at Rf = 1.2 5% at Rf = 1.5 10% parent at Rf = 2.5. Varrone et al.118 | 0.05 (Piramel Investigator’s Brochure; confidential) |

| [11C]DPA-713 | Ki against [3H]PK11195 in human brain tissue: 15 nM (HAB) 66 nM (LAB). Owen et al.113 | 95% at 10 min 60% at 60 min. Endres et al.146 | Rf of plasma metabolites not reported in literature | 0.09 Endres et al.146 |

| [18F]DPA-714 | Ki against 2 nM [3H]PK11195 in rat heart membranes: 0.9 nM, allelic dependence unknown. Damont et al.154 | 90% at 10 min 70% at 60 min. Golla et al.148 55% at 90 min. Lavisse et al.106 | At 60 min p.i. (baboon) 40% at Rf = 0.2 10% at Rf = 2.4 10% at Rf = 3.0 25% parent at Rf = 3.5 15% bound to pellet. Peyronneau et al.135 | 0.05 (baboon). Saba et al.91 |

| [18F]PBR111 | Ki against [3H]PK11195 in human brain tissue: 16 nM (HAB) 62 nM (LAB). Owen et al.113 | 40% at 10 min 20% at 60 min (baboon; Eberl et al.130 60% at 10 min with blocking (baboon; Katsifis et al.155 | At 60 min p.i. (baboon), analysed by solid phase extraction: 70% hydrophilic 10% lipophilic metabolite 20% unchanged parent. Katsifis et al.155 | 0.05 ± 0.02 Guo et al.127 |

| [123I]CLINDE | KD 4 nM rat brain cortex membranes. Mattner et al.156 | 37% at 10 min 21% at 90 min. Feng et al.157 | At 60 min p.i. 30% at Rf = 0 23% at Rf = 6.3 41% parent at Rf = 9.5 Dr Ling Feng, personal communication | 0.024 Dr Ling Feng, personal communication |

| [11C]ER176 | Ki against [3H]PK11195 in human cerebellum: 1.9 nM (LAB) 1.5 nM (HAB). Zanotti-Fregonara et al.125 | 90% at 10 min 25% at 60 min (rhesus monkey). Zanotti-Fregonara et al.125 | Plasma metabolites (rhesus monkey) eluting at 3.6, 4.8, 5.9 and 7.2 min, and parent at 9.4 min. Percentages unspecified, Rf unknown. Zanotti-Fregonara et al.125 | 0.033 Ikawa et al.126 0.080 at baseline and 0.12 after pre-blocking in baboon. Zanotti-Fregonara et al.125 |

| [18F]GE180 | KD rat brain 0.9 mM. Wadsworth et al.136 Ki against [3H]PK11195 binding, human platelets: 2.5 nM (HAB) 38 nM (LAB) (GE Investigator’s Brochure) | 85% at 10 min 75% at 60 min. Fan et al.138 | At 15 min p.i. 5% at Rf = 0.0 20% at Rf = 0.2 15% at Rf = 0.4 70% parent at Rf = 0.9. Fan et al.138 | 0.03 Feeney et al.139 |

HAB: high affinity binding; LAB: low affinity binding.

Findings in human unless otherwise specified. The dissociation (KD) and inhibition constants (Ki) were measured in vitro using preparations as specified. Findings for percentage unmetabolized parent in plasma at different circulation times, and the retention factors (Rf) of the labelled compounds are (except where specified otherwise) obtained by HPLC analysis of plasma extracts from human subjects. Plasma free fractions (fp) were measured by rapid membrane centrifugation of spiked plasma samples.

History of PBR/TSPO

The binding of [3H]diazepam in membranes prepared from brain tissue mainly represents the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-A receptor complex. However, its binding sites in peripheral tissues are pharmacologically distinct, being highly sensitive to displacement by Ro-4864, which is inactive at displacing [3H]diazepam from brain membranes.36 Ro 5-4864 (4-chlorodiazepam) and subsequently the isoquinoline carboxemide PK11195 were identified as selective ligands for the [3H]diazepam binding site in peripheral tissues.36–38 Originally termed PBR, this site was long something of an enigma, with no clearly established function or endogenous substrate. However, some studies implicated PBR in cholesterol transport and steroid synthesis.39–41 In 2006, PBR was renamed TSPO42 to reflect its functional attribution in the transport of cholesterol across the mitochondrial membrane.43–45 Indeed, the TSPO binding site is highly expressed in steroidogenic tissues such as the adrenal cortex46 and Leydig cells of the testes. However, membrane binding studies with [3H]Ro 5-4864 also revealed the presence of TSPO in the central nervous system, albeit at concentrations less than 5% of that found in peripheral tissues.47 This and several other early studies indicated an upregulation of TSPO in seizure models, which may be considered the initial phase of what has since become an extensive literature on TSPO as a marker for pathology of epilepsy19 and by extension a wide range of neuroinflammatory conditions.

The gene encoding TSPO was cloned,48,49 and proved to be highly conserved across many living organisms.50–52 Indeed, TSPO has homologues in bacteria,45 insects,52 plants,53 and mammals.51 In 2015, the TSPO homologs from Rhodobacter (RsTSPO)54 and Bacillus cereus (BcTSPO)55 were crystalized for high resolution X-ray diffraction studies. This confirmed the presence of five structural transmembrane domains, as had been predicted from the amino acid sequence, and revealed the position of the PK11195 binding pocket.54–57 Furthermore, the structural studies of bacterial TSPO revealed the nature of the dimer interface, and elucidated an important functional polymorphism (Ala(147) → Thr(147); A147T) of human TSPO with respect to affinity changes for PK11195, as well as potential endogenous substrates cholesterol and protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). As shall be seen below, this polymorphism has important consequences for the interpretation of TSPO-PET results.

TSPO function

The ubiquity of TSPO in so many tissues of diverse organisms implies a key role in basic cellular processes. An initial attempt to knockout the TSPO gene in mice failed due to embryonic lethality.58 While this suggested an essential role for TSPO in embryogenesis, that study did not report details of the techniques, including the genetic constructs employed. Subsequently, TSPO knockout mice were successfully generated, and in long-term observations9 showed no conspicuous loss of vitality or any aberrant physical phenotype. Viability of TSPO conditional and global knockout mice has been confirmed by numerous other studies.9,59–62 As noted above, TSPO had initially been reported to be critical for cholesterol transport across the mitochondrial membranes, as required to initiate the first step of steroid biosynthesis.42 The A147T polymorphism of human TSPO lies adjacent to the cholesterol recognition consensus sequence (CRAC), suggesting a mechanistic basis for impaired steroid metabolism attributed to that allele.63 However, studies of TSPO knockout mice under normal physiological conditions did not reveal overt phenotype alterations in steroid metabolism.59–62 These observations require confirmation in TSPO knockout mice under conditions of physiological stress, where steroid homeostasis may be perturbed.

Other postulated functions for TSPO include an interaction with the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP),42,64–66 the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as participation in aspects of cell proliferation,67 apoptosis,68 immune modulation,46 and mitochondrial respiration.43 Indeed, mitochondrial ATP production is attenuated in microglia cultured from TSPO knockout mice, consistent with some role for TSPO in mitochondrial energy production.9 This aspect of TSPO is also supported by results of a recent study involving insertion of the TSPO gene into a human T-lymphocytic leukaemia cell line (Jurkat), which normally have little TSPO expression due to extensive methylation of the promotor region.69,70 The TSPO gene insertion increased transcription of genes involved in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, thus elevating mitochondrial ATP production, as well as cell excitability. These functional changes were accompanied by increased cell proliferation and motility in vitro, which were inhibited by PK11195 treatment.69 Furthermore, fibroblasts from TSPO knockout mice have decreased oxygen consumption rate and lower mitochondrial membrane potential.71 There was an energy production shift from glycolysis to mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, and a concomitant increase in ROS production in MA-10 Leydig cells after knockout of TSPO by CRISP/Cas9 method, which supports a specific role for TSPO in cellular metabolism of steroidogenic tissues.72

Cellular location and abundance

Binding sites of TSPO ligands such as [3H]Ro5-4864 and [3H]PK11195 are primarily located in mitochondria, but some binding is also reported in other subcellular organelles and in the plasma membrane.73 Similarly, immunostaining has shown the presence of TSPO sites in the nucleus and perinuclear area within human cancer cells.74,75 Here, the extent of nuclear distribution of TSPO correlated positively with the degree of tumour aggressiveness. Immunostaining has also revealed nuclear and perinuclear localisation of PBR/TSPO in rat microglia and astrocytes.76 Subcellular locations of TSPO expression in cultured astrocytes include the outer mitochondrial membrane, plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum, nuclear membrane and centrioles.77 On the other hand, recent studies entailing stable transfection and transient transfection of organelle-CellLight in human cells showed that TSPO localised only in the mitochondria.69 Double immunohistochemical analysis reveals TSPO expression in microglia and astrocytes of rats with cuprizone-induced neuroinflammation.78 However, the relative contribution of the two cell types to TSPO expression is unknown, nor is it certain that this proportion is the same in healthy brain and a neuroinflammatory condition. Furthermore, Lavisse used lentiviral gene transfer of the cytokine ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) to induce astrocytosis into the rat striatum, without causing neurodegeneration.12 In that study, double immunofluorescence, also with GFAP and IBA1, revealed elevated TSPO expression in astrocytes, but little increase in microglia, leading the authors to conclude that increased TSPO binding to [18F]DPA714 small animal PET was in the main due to astroglial activation.

In addition to TSPO expression in cells native to the brain parenchyma, immunologically active cells such as monocytes and polymorphonuclear neutrophils express TSPO.79 Monocytes and polymorphonuclear neutrophils, although normally excluded from brain, may gain access following brain injury or as part of a systemic immunological reaction.80 In addition, there is concordance between TSPO binding measured by brain PET and in lymphocytes from healthy individuals, indicating a shared regulation of expression, and raising the possibility of a physiological infiltration of lymphocytes to brain.81 In the circumstance of an acute inflammatory reaction, arrival of blood-derived cells may account for rapid increases in brain TSPO binding, as in the case of LPS intoxication cited above. However, TSPO expression increases substantially in rodent-derived macrophages and microglia upon pro-inflammatory stimulation, but not in primary human microglia.82 Indeed, pro-inflammatory activation of human monocyte-derived macrophages reduced TSPO gene expression.

In general, an effective PET ligand should have high affinity and specificity for its intended binding site, which in turn should have high abundance in the target tissue. The absolute abundance or concentration (Bmax) of ligand binding sites in brain tissue and the dissociation constant (KD) are assessed by saturation binding studies in membrane preparations, or by quantitative autoradiography using a range of radioligand concentrations, ideally extending one order of magnitude above and below the KD. In vitro binding assays with [3H]-(R)-PK11195 in normal mammalian brain concur in showing a single binding site with approximately two-fold range in the Bmax between the highest (thalamus) and lowest (white matter) binding regions, with cortical Bmax typically in the range 60–600 pmol g−1, and KD in the range of 2–31 nM.10,83–87 While saturation binding results vary considerably due to procedural and species differences, these findings indicate abundant constitutive expression of TSPO throughout healthy mammalian brain at a density similar to that of well-known targets such as dopamine D1 and D2 receptors88 and dopamine transporters in rat and primate striatum.89 Thus, the ubiquity of TSPO sites throughout healthy brain emphasises the lack of a reference region devoid of displaceable binding, and indicates that any TSPO increases due to inflammation project upon a background of constitutive expression.

The in vitro Bmax/KD ratio for [3H]-(R)-PK11195 predicts an in vivo binding potential (BPND) in the range of 13–100, again similar to estimates for striatal dopamine markers, which should favour the detection of TSPO by PET. However, the low [11C]-(R)-PK11195 binding to PET (BPND < 1) suggests that factors such as low free fraction of the radioligand in brain and/or competition from endogenous ligands conspire to reduce the specific binding signal in molecular imaging studies.85 Furthermore, TSPO ligands can evoke allosteric modulation of their own binding, and unknown factors may influence the equilibrium for TSPO in its dimeric and trimeric states, with possible consequences for ligand affinity in vivo.90 Alternately, temperature-dependent changes in affinity state might influence ligand binding in laboratory conditions, as is reported for binding of [3H]diazepam to GABA-A binding sites in rat brain membranes.36 Some similar phenomenon might conceivably render TSPO binding assays highly sensitive to laboratory temperature or other experimental factors, such as the particulars of buffer composition or even pharmacological effects of anaesthetic agents. For example, the Bmax of [18F]DPA-714 in homogenates from baboon brain (32 pmol g−1) increased by 33% in the presence of propofol, whereas the affinity decreased five-fold, but isoflurane had no such effect.91 As such, when undertaking and assessing quantitative PET studies, anaesthesia or other pharmacological treatments may alter the binding properties of TSPO sites by mechanisms unrelated to microglial reactions per se.

Approaches to PET quantitation

In the present context, the objective of quantitative PET analysis is to obtain an index of the abundance or concentration of the TSPO binding site in living brain, i.e. the Bmax. The saturation binding parameters Bmax and KD can be estimated separately from serial PET studies entailing a range of ligand specific activities, as in a rat PET study with the MAO-A ligand [18F]-fluoroethylharmine.92 However, this fully quantitative approach is technically very demanding, and an initial attempt for the case of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 failed due to the low specific binding in brain of living pigs.85 The simplest form of quantitation for routine PET studies consists of scaling the regional uptake at some time-window after tracer administration to the total injected dose (standard uptake value: SUV). The SUV may be preferred as a matter of convenience or logistics, as it is obtained non-invasively, while using standard procedures for nuclear medicine evaluations. However, SUV scores reflect the composite of many dynamic processes, and are most indicative of TSPO concentration in brain for tracers with inherently low non-specific binding, such as is the case for [11C]PBR28, which was apparently 95% displaceable from brain of living baboon.93 Thus, the [11C]PBR28 VT in healthy humans correlated well with SUV, but not reference region normalized standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR), leading the authors to conclude that dividing by a denominator region removed most of the biologically relevant signal.94 Others however report that measurements of an occipital cortex SUVR index captured the increases in [11C]PBR28 VT in brain of patients with an neuroinflammatory condition, i.e. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.95 Likewise, SUV analysis of [11C]PBR28 uptake in baboon brain failed to indicate the immunological activation of TSPO by LPS treatment that could be discerned by a more physiologically defined metric, the Logan VT.96 Furthermore, an SUV index was scarcely fit to discriminate binding of the SPECT ligand [123I]-CLINDE in brain of healthy high binders (BPND 3.8) and low binders (BPND 1.9).97 The authors attributed this failure of SUV to the confounding effects of binding to blood and other peripheral cells, but did not explore the possibility of scaling SUV to some pseudo reference region.

At issue is the need to separate indices of the TSPO-specific (VS) and non-displaceable (VND) binding components in the PET SUV signal. The sensitivity of SUV scores for detecting pathology is often improvable by globally scaling brain uptake to some pseudo-reference region (SUVR) where TSPO binding is relatively low, and unaffected by any disease process. For example, scaling [11C]-(R)-PK11195 SUV to the white matter radioactivity concentration revealed diffuse increases in patients with HIV, irrespective of their dementia status.98 While the SUVR signal was low in magnitude, the effect size in that study was considerable (Hedges g > 1), suggesting that precision had been enhanced by the scaling procedure. However, the physiological interpretation of SUV/SUVR is subject to various caveats, and the selected time frame should coincide with the transient equilibrium of the radioligand binding to TSPO sites in brain, in consideration of possible blood flow effects on tracer delivery, binding and washout.

A more quantitative approach is to record an extended dynamic PET sequence, and then estimate the specific binding component relative to a reference region assumed to be devoid of specific binding. The dynamic time–activity curve in the region of interest can then be decomposed into its specific and non-specific binding components, from which can be calculated a dimensionless index of the specific binding, known as the binding potential (BPND). This is a steady-state index, corresponding to the ratio of the two rate constants (k3/k4) describing the reversible binding of the free radiotracer in brain. Here, k3 is the rate constant for association of the PET ligand with the binding site (which is proportional to the local concentration of the binding site), and k4 is the dissociation rate constant. The most widely used approaches for estimating BPND are the Logan reference tissue method and the simplified reference tissue method (SRTM).99 In general, the validity of a non-binding reference region is best supported by prior knowledge of the distribution of the binding site in question, or confirmed by formal demonstration of its resistance to pharmacological displacement. This condition is demonstrably met for molecular targets such as dopamine transporters, which are nearly absent from cerebellum.89 On the other hand, the presence of a small specific binding component for dopamine D2/3 receptors in cerebellum (1% of striatum values100) brings considerable bias to the quantitation of BPND in some brain regions.101

Although the cerebellum and the white matter have relatively low TSPO density, there is no brain region totally devoid of TSPO binding sites.85 As such, reference tissue methods will systematically underestimate the true BPND. Efforts have been made to approximate the requirement for a valid non-binding reference region by using a pseudo-reference region, contaminated to some unknown extent by a specific binding signal. In a representative case of that approach, the cerebellum was used as a pseudo-reference region for calculating [11C]-(R)-PK11195 BPND in brain of patients with schizophrenia.102 As above, it must be recalled that the BPND calculated in this manner will vary inversely with the real specific binding present in the pseudo-reference region, which may be considerable in the case of the ubiquitous TSPO site. Furthermore, the extent of this violation may change with disease or treatment history, if these factors perturb TSPO expression in the pseudo-reference region.

Data-driven procedures present an alternate to such an arbitrary selection of a pseudo-reference region. In the supervised clustering approach, voxel-wise time activity curves are grouped into a small set of tissue types, aiming to isolate voxels in which the signal is contaminated by ligand binding in then vascular compartment, a possibility which must be considered in quantitative TSPO studies.103 In that study, scaled voxelwise [11C]-(R)-PK11195 dynamic data were assigned to one of six predefined kinetic classes: grey matter, white matter, pathological TSPO binding (i.e. Huntington’s disease), blood pool, skull and muscle. BPND was then estimated by a procedure of rank shaping exponential spectral analysis (RS-ESA). This procedure gave a BPND of about 0.5 in normal cerebral cortex versus approximately 1.0 in pathological tissue. This is somewhat lower in magnitude than the physiological BPND defined by the Lassen plot (Table 1), suggesting a certain bias due to imperfect identification of the non-specific binding. When applied to dynamic [11C]-(R)-PK11195 data from healthy subjects, another algorithm assigned voxelwise dynamic data to one of 10 clusters according to shape, and identified a pseudo-reference cluster for its similarity to control data; maps of BPND calculated relative to this population-based reference input revealed foci of elevated binding in patients with multiple sclerosis.15 So calculated, the BPND was as high as 1.0 on some demyelinating lesions, indicating a substantial elevation of specific TSPO binding in association with neuroinflammation. In other applications, the cluster analysis approach has revealed disease-specific patterns of microglial activation in patients with multiple system atrophy,104 and tracked the spread of inflammation in patients with herpes encephalitis.29 In the latter condition, where the pathology is largely confined to the hippocampus, there was a high correlation (r > 0.94) between regional BPND values estimated using reference tissue cluster analysis compared with BPND calculated from a cerebellum reference tissue template. However, the scatter plot of the results by method showed an offset favouring BPND calculated by the cluster reference method.

In another [11C]-(R)-PK11195 PET study, a cluster-derived pseudo-reference region gave good separation of the BPND estimates between healthy controls and patients with Alzheimer’s disease.105 Putting aside the potential for circularity due to selecting a method based on its discriminative power, the latter study highlights how group differences supposedly indicative of disease pathology are vulnerable to bias arising from subtle factors, such as the criterion for defining the reference region, and the possible contribution of intravascular binding to the PET signal, noted above. While the data-driven approach may seem preferable to using cerebellum or white matter templates as a pseudo-reference region, the resultant BPND results are vulnerable to bias from uncorrected contamination of the reference cluster by specific binding. Supervised cluster analysis of [18F]DPA-714 uptake in healthy human brain shown the preponderance of reference voxels to be within the cerebellum; the forebrain BPND was the range of 0.2–0.6, with little effect of TSPO allele.106 This magnitude of BPND is low compared to other reports with [11C]DPA-713 and [18F]DPA-714 (Table 1), suggesting that the reference cluster indeed underestimates the specific binding.

We have thus far considered non-invasive PET analyses, where one obtains the index of TSPO binding sites from consideration of the brain uptake only. However, compartmental analysis relative to the metabolite-corrected arterial input function is in general the gold standard method for the evaluation of tracer uptake in brain. In the simplest instance of the one tissue-compartment model (1TCM), the tracer in arterial blood is assumed to enter brain at a rate defined by the unidirectional clearance (K1), which has the same units as a cerebral blood flow (CBF) (ml g−1 min−1). The unbound tracer in brain returns to circulation by a simple diffusion process (k2; min−1). Knowing the brain TAC and the arterial input function, the two microparameters can be estimated by non-linear fitting of the 1TCM. Their ratio K1/k2 represents the steady-state partitioning of the tracer between brain and blood (VT; ml g−1), which can be calculated from linearizations such as the Logan arterial input plot. This procedure conflates the specific binding component with the total distribution volume. Thus, the global mean VT for [11C]-(R)-PK11195 in brain of healthy volunteers (1.08 ml g−1) is the composite of VS, the TSPO specific binding, and VND, the non-specific binding of the tracer in brain.107 Compartmental analysis or displacement studies can identify the proportions of these two binding components, as discussed below.

The two-tissue compartment model (2TCM) optimizes the fitting of the brain time–activity curve for all four microparameters, K1/k2/k3/k4. This approach has face validity, in that it accommodates something of the real complexity of the dynamic process of tracer distribution. Indeed, in most of the compartmental analysis studies for TSPO tracers summarized in Table 1, the 2TCM was superior to the 1TCM based on the Akaike information criterion, which calculates the trade-off between model complexity and likelihood (goodness of fit) for models using a given set of data. Nonetheless, the 2TCM is vulnerable to model over-specification, as reported for the opioid receptor ligand [18F]cyclofoxy,108 whereas estimation of the macroparameter VT is inherently more stable than attempts to separate its constituent microparameters. It is by no means certain that the 2TCM gives an optimal trade-off in the independent estimation of all four parameters. A ‘truth test’ for the results of a 2TCM analysis is that the ratio of the microparameters K1/k2 should be equal to the magnitude of VND, were that known from experiments with displacement. Based on Monte Carlo simulations for [11C]-(R)-PK11195 binding, the stability of the main parameter of interest (BPND; k3/k4) is improved by globally constraining VND (K1/k2) to the observation in cerebral cortex.109 In general, this constraint approach yields higher BPND in brain than is typically found with the pseudo-reference tissue methods noted above, suggesting that bias due to specific binding in the reference region can be partially averted. The stability of a 2TCM for identifying the parameter of main interest (BPND) can be ascertained when gold standard estimates of VND are available, either from Lassen plots or by graphical analysis relative to allelic status. By this criterion, the fitness of the 2TCM can only be judged for 7/13 cases presented in Table 1; the 2TCM estimate of BPND roughly matched a constrained VND result in the case of [11C]PBR28. However, the 2TCM BPND was two-fold overestimated in four cases ([11C]PK11195, [18F]FEPPA, [11C]DPA714, [18F]GE180), and was about 50% underestimated for [11C]PB111 and [123I]CLINDE. In effect, the 2TCM gives an unpredictable trade-off between estimates of VND and BPND, unless some constraint is applied to VND.

In consideration of TSPO binding sites purportedly present in the vascular compartment, Rizzo et al. have introduced a modified 2TCM with an additional parameter describing the binding of [11C]PBR28 to the endothelium, i.e. the 2TCM-1K model.110 This fitting procedure suggested that less than 50% of the specific PET signal corresponds to binding sites in the brain parenchyma. A more recent test of the 2TCM-1K model indicated that some 20% of the 18F-DPA-714 VT in healthy humans could be associated with an endothelial compartment, and that this binding component correlated with library results for the expression of endothelial mRNA markers.111 The addition of the endothelial binding compartment brings a risk of over-specification, but the veracity of the interpretation could be determined though displacement studies with a TSPO blocker confined to the vascular compartment in vivo, were such a compound available.

As noted above, the allelic dependence of TSPO binding in human brain was discovered fortuitously in a [11C]PBR28 study, where aberrantly low binding was noted in one individual,34 and confirmed in a subsequent study showing absence of specific binding in two of 12 healthy human subjects.112 Homogenate binding studies using post mortem human brain tissue showed two populations of binding sites of [3H]PBR28, with KDs of approximately 1 and 100 nM.83 In contrast, binding studies with [3H]PK11195 in the same material showed only a single population of binding sites (Table 2). These observations have subsequently been extended to several other new generation TSPO ligands (i.e. DAA1106, DPA713, and PBR111), all of which indicated distinct affinity states, albeit not always with the same affinity ratio.113 The binding affinity of PBR28 in platelets from a series of humans showed a relation to a single nucleotide polymorphism of the TSPO gene on chromosome 22q13.2, namely rs6971, which gives rise to Ala147Thr.114 This polymorphism accounts for the stratification of [11C]PBR28 VT115 and [18F]FEPPA116 in groups of healthy human subjects. By convention, individuals carrying two HABs, as distinct from heterozygotes or mixed affinity individuals (MABs) and homozygotic low affinity bindings (LABs). In a [18F]DPA-714 study of baboons, two animals had low binding (VT = 6 ml g−1), whereas three animals had high binding (VT = 20 ml−1,117). This study did not report genotyping, but the implication is that allelic variants is a general aspect of TSPO binding sites in primates, as distinct from rodents, which are not thought to have functional alleles.

For TSPO quantitation, the correct estimation of the non-displaceable binding component is of paramount importance. Some have estimated VND for the case of [18F]FEDA1106 from a Logan plot of the first 15 min of the PET recording, during which time equilibrium is not attained,118 this VND proved to be systematically 25% lower than that calculated from 2TCM. The ground truth might best be determined by experiment, in which brain uptake is measured at baseline and in a condition of complete pharmacological blockade of TSPO. However, this approach is invalid for SUV analyses, as pharmacological blockade of TSPO sites in peripheral tissues greatly increases the bioavailability of tracer in circulation. Thus, the SUVs of [11C]PBR28 and [18F]FEPPA in brain of rats measured ex vivo were seemingly unaffected by treatment with blocking doses of non-radioactive FEPPA and PBR28, respectively.119 Upon correcting the SUV for the actual plasma radioactivity concentration there was seen a 75% displacement for the case of [11C]PBR28 and 90% displacement for [18F]FEPPA. A more quantitative approach for estimating specific binding is obtained by testing effects of pharmacological blockade on the magnitude of VT, which is inherently robust to changes in bioavailability, although it requires the invasive arterial sampling approach. In one such study, the VT of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 in brain of non-human primate was reduced by approximately 50% after pre-treatment with PBR28 at a dose of 5 mg/kg, indicating a BPND close to unity.120 Other displacement studies in vivo have suggested 80% specific binding in [11C]DA1106 in brain of non-human primate, indicating a BPND of approximately 3.121

Complete pharmacological blockade of TSPO sites may not be convenient in clinical PET studies (although acute toxicity has not been reported), but the magnitude of VND can also be estimated by extrapolation of the Lassen plot, where VT is measured in a setting with two PET scans, i.e. a baseline condition and in a partially blocked condition. Here, [11C]-tracers bring a distinct advantage in that the brief physical half-life enables two PET recordings in a single session. Only a few TSPO PET studies have so far undertaken the Lassen analysis. In one such investigation using the TSPO blocker ONO-2952, the VND for [11C]PBR28 was 14.2 ml g−1 in brain of non-human primates, indicating a BPND of approximately 4 in monkey frontal cortex.122 The recent report of Frankle et al. may set a new standard for the quantitation TSPO sites in living human brain.123 Here, the VT of [11C]PBR28 was measured in brain of healthy volunteers at baseline and after challenge with ONO-2952. By applying the Lassen plot, the authors established the VS-to-VND ratio, calculating a cortical BPND of 0.5 in MABs and 1.3 in HABs relative to VND of 2 ml g−1.122 This approach has become accessible with the advent of TSPO blockers approved for human use. It is unclear why the Lassen-based VND and BPND results differ so greatly between human and non-human primates, or indeed why the human BPND falls so short of the expectation based on the nearly complete pharmacological blockade of [11C]PBR28 in non-human primates, but there is clearly a need for more displacement studies. In another study employing Lassen analysis, the [11C]-(R)-PK11195 VND in human brain was close to 0.4,124 matching the estimate obtained by fitting a 2TCM, and consistently indicating a BPND estimate of about 0.8, irrespective of TSPO allelic status (Table 2). In the same study, Lassen analysis showed the [11C]DPA713 VND to be 0.42 in human brain, predicting a cortical BPND of 7.3 in HAB subjects, versus 1.8 in LAB subjects; the relatively high binding in the LABs is consistent with the incomplete allelic selectivity reported for this ligand in vitro (Table 1).

Recently, a series of 4-phenylquinazoline-2-carboxamides have been developed which substantially lack allelic sensitivity to the human single nucleotide polymorphism rs6971 in vitro.125 This property may be related to the structural similarity of [11C]ER176 and related compounds with the prototype TSPO ligand PK11195, which is likewise indifferent to allelic status. Lassen analysis of [11C]ER176 binding changes in human brain upon displacement by XBD173 indicated a VND of 0.65 ml g−1, suggesting a cortical BPND of about 3.5 in a group of three HAB subjects.126 Despite its low allelic sensitivity in vitro, [11C]ER176 PET indicated a somewhat lower BPND in LAB subjects, albeit this difference being based on only two subjects.

With certain caveats, the existence of TSPO polymorphisms in human populations affords an alternate to blocking studies for the estimation of VND, at least for those tracers with very high selectivity for the HAB allele in vitro (and with the assumption that this selectivity is preserved in vivo). In this scenario, VT in a HAB individual represents the sum of VND and the specific binding contribution of two HABs, whereas VT in a MAB individual has only one unit of VS. Hence, one can estimate the population mean VND by algebra or graphical analysis of VT as a function of allelic status, without necessitating a pharmacological displacement. Using the population-based and indirect VND estimate, BPND is then calculated from the individual VT estimates. Several instances of this approach are presented in Table 2. For the case of [18F]DPA-714, this procedure gives a two-fold higher BPND in the HAB group than in MAB, a difference that was not evident using the ordinary unconstrained (and over-specified) 2TCM. This typical instability of the 2TCM is also evident from the disparate estimates of VND for the case of [18F]PBR111, which ranged from 1.0 to 2.0 ml g−1 depending on the allelic status.127 A graphical/algebraic analysis of cortical VT measurements in the HAB and MAB groups gave a VND of 0.93 ml g−1, which suggests a spuriously high BPND of 1.4 in the LAB group (Table 2). Graphical analysis of the cortical VT data from the HAB and LAB groups gave a VND of 1.4 ml g−1, from which one calculates a more plausible BPND of 0.6 in the LAB group. However, the whole validity of this approach for estimating the non-displaceable binding rests on the premise that the LAB allele has negligible specific binding. While this assumption is likely valid for [11C]PBR28, which has a 100-fold difference in affinity in vitro, the four-fold affinity difference of [18F]PBR111 likely results in some specific binding signal for LABs. Displacement studies could resolve this conundrum by giving an unambiguous estimate of VND, irrespective of the extent of specific binding inherent to the LAB allele.

There have been relatively few test–retest studies of the quantitation of TSPO, which is unfortunate, as this is the only means to separate biological variation from experimental variance. Knowledge of test–retest covariance (%COV) supports power calculations, and thus the prediction of adequate group size for detecting a treatment effect. Furthermore, %COV can constitute an objective basis for choosing one TSPO tracer or endpoint over another. For the case of [11C]-(R)-PK11195, the %COV of the endpoint BPND in grey matter calculated by 2TCM was 18%.128 In contrast, the VT of [18F]FEDAA1106 had a %COV of only 3% in grey matter, versus 7% in white matter,118 predicting substantially higher power for detecting upregulation of TSPO. For the case of [11C]PBR28 in humans, the interclass correlation of the endpoint VT was at least 0.9 in all grey matter regions, and the absolute variance within the population was 15–18% depending on the particulars of the study; variability was two-fold higher in white matter regions.129 The intraclass correlation coefficient for repeat measures of [123I]CLINDE VT was 0.58 in a group of healthy MABs versus 0.80 in HABs.97 Thus, the precision of the estimate is higher in those with higher binding.

Metabolism and plasma protein binding

There are relatively few detailed characterizations of the metabolism of TSPO ligands. In one such study, incubation of PBR102 and PBR111 with rat microsomes showed dealkylation and hydroxylation to be the predominant pathways, with lesser metabolism by human microsomes.130 We summarize the metabolism of 13 tracers that have been employed in quantitative molecular imaging studies of TSPO in healthy human brain (Table 1). There is substantial metabolism of most of these tracers during a dynamic PET/SPECT examination, such that proper quantitation of brain uptake entails chromatographic analysis of extracts from plasma derived from serial arterial blood sampling. However, the plasma metabolism of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 is relatively slow, with 80% of plasma radioactivity remaining as unmetabolized parent tracer at the end of 1 h in humans; two main metabolites were detected, of which the relatively lipophilic metabolite eventually constituted 10% of plasma radioactivity.128 Even if entering brain, this metabolite could contribute only slightly to the non-specific binding signal. In many cases, the predominant plasma metabolites of PET tracers are hydrophilic species (Table 1), which are less likely to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB).

Plasma metabolites with high retention factor (Rf) to reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are likely to have significant BBB permeability. Unfortunately, radiochromatograms allowing Rf calculations are only available for eight of the 13 tracers presented in Table 2. Some of these ([18F]FEPPA, [18F]FEMPA, [18F]PBR06, [18F]GE180, and [123I]CLINDE) come to have substantial amounts of plasma metabolites with Rf at least one half that of the parent compound; indeed, a moderately lipophilic metabolite of [18F]-FEPPA represented 40% of plasma radioactivity in humans later than 30 min post injection.131 Especially in this case, the lipophilic plasma metabolite may well comprise some relevant proportion of the brain PET signal. In the case of [18F]PBR06, distortion of the late phase of brain time activity curves has been attributed to the presence in brain of plasma metabolites.132

Radio-HPLC analysis of brain extracts from experimental animals is required to confirm the presence of brain-penetrating metabolites, with the caveat that species differences may have unpredictable effects of metabolite profiles. If a tracer metabolite is present in plasma and brain extracts from rodents, and if radio-HPLC analysis reveals the same compound in non-human primate or human blood samples, then one may predict for contamination of the brain signal in human PET studies by that metabolite. Although metabolites with high Rf may have favoured access to the brain, polar metabolites of certain PET tracers may come to constitute up to 30% of the total radioactivity in rat brain extracts,133,134 which would certainly result in biased quantitation of specific binding. In the case of [18F]DPA714, a carboxylic acid metabolite constituted as much as 15% of the radioactivity in rat brain,135 whereas [18F]GE180 metabolites constituted less than 10% of brain radioactivity.136 While there is no defined upper limit for acceptable brain levels of peripheral metabolites, their presence will also result in bias and reduced accuracy of endpoints related to specific binding.

Many PET tracers in circulation are substantially bound to serum albumin. In the case of [3H]-(R)-PK11195, the predominant binding component is with α1-acidic glycoprotein.137 Since expression of this protein increases with infection, it follows that systemic inflammatory status may alter the plasma kinetics of the PET tracer [11C]-(R)-PK11195. Furthermore, the physiologically-defined endpoint VT should arguably be corrected for the fraction of unbound, freely exchangeable tracer in the plasma compartment, fp. As such, the uncorrected binding of TSPO ligands to plasma proteins in inflammatory conditions has been invoked as a limitation of a study of [11C]PBR28 binding in schizophrenia.27 The authors of the original report responded by noting that the magnitude of fp is too low for reliable measurement, in effect thus arguing in favour of precision over accuracy. Indeed, TSPO ligands have plasma free fractions generally less than 5% (Table 2), and there is sometimes considerable discrepancy between research groups. When both VT and VT/fp are reported, the substantial scaling can be accompanied by an apparent increase in the variance, as in the case for [11C]PBR28.127 While scaling to fp increased the gap between mean VT results for HAB and MAB groups, this difference was not significant, suggesting an unfavourable trade-off between precision and accuracy. On the other hand, there was no consistent effect of scaling to fp on the precision of VT for the case of [11C]ER176.126

The magnitude of fp is measured at steady-state, usually by centrifugation of a plasma sample through a membrane that is impermeable to plasma proteins, although dialysis membrane methods can afford greater sensitivity. One then calculates the free fraction from the radioactivity concentration in the protein-free filtrate. However, the binding of a PET ligand to serum proteins is a reversible and saturable process. At issue is the kinetics of the binding; if the on/off rates are of comparable magnitude to the transit time through the brain capillary bed (about one second), then the protein-bound tracer is still available for entry into brain. That this is in fact the case is attested by the high K1 seen for most TSPO tracers, which are calculated relative to the whole blood tracer input function without and correction for fp. Extraction fraction (EF) is defined as K1 divided by CBF, which has a canonical value in human grey matter of 0.5 ml g−1 min−1. As such, the EF of 11 of the 12 tracers considered in the present study is approximately 50% (Table 2). An exception is presented by [18F]GE180, which had an EF of only 3%, which may well account for its low specific binding in human brain.138,139 The [18F]GE180 fp in human plasma (3%) is typical of other TSPO tracers with better brain penetration, but it may be that the dissociation kinetics for [18F]GE180 binding to human plasma proteins disfavour uptake during transit across the BBB. [18F]GE180 is an admirably fit tracer for TSPO imaging in glioma, a condition with BBB disruption,140 and is a sensitive tracer for TSPO activation in rodent brain,141 thus suggesting an important species differences in permeability of that tracer to the BBB.

The great bulk of TSPO sites are found in peripheral tissues; as such, substantial amounts of PET tracers are rapidly ‘removed from play’ after intravenous injection, but may be mobilized back into circulation after systemic pharmacological blockade, as noted above. Thus, TSPO blockade increased the unmetabolized parent fractions of the corresponding [18F]-labelled TSPO tracers in baboon blood samples.130 This is a general phenomenon for TSPO tracers, likely depending on individual allelic status. Consequently, the significantly lower fp of [11C]PBR28 seen in HAB individuals113 predicts for a larger bound pool in peripheral organs, which will be mobilized in the circumstances of a blocking study. This phenomenon also raises a red flag about the SUV method, since bioavailablity of tracers may then depend upon allelic status. For similar reasons, the fp of [11C]ER176 increased from 3.3% to 4.1% upon treatment with a blocking dose of XBD173, suggesting partial saturation of the plasma protein binding. However, this may be a moot point, since correction for fp was without much systematic effect on the precision of the estimate of VT, or the distinguishability of binding in relation to TSPO allelic status, as noted above.126

Conclusions

PET and SPECT studies of TSPO play a crucial role in the fledgling study of neuroinflammatory components in many neuropsychiatric disorders. However, several important caveats emerge from our systematic review of the 13 TSPO ligands so far investigated by compartmental analysis in humans. These caveats highlight the need for caution when undertaking translational molecular imaging of TSPO-based tracers, and may have broader applicability to the general question of how to select from among a range of available tracers for a given molecular target. The minimum requirements of pharmacological specificity and high affinity in vitro should be established at the earliest phase of tracer development. While [11C]-labelled tracers are preferable in terms of radiation dosimetry, they are not widely available for routine use, in part due to the 20 min physical half-life. The allelic insensitivity of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 binding can be advantageous for research studies, although [11C]PBR28 has a considerably higher BPND. The logistics for distribution of [18F]-labelled tracers are favoured by the 109 min physical half-life. Among the various [18F]-labelled TSPO tracers documented to date in humans, [18F]DPA-714 apparently has the highest specific binding (based on one report). The three tracers [18F]FEPPA, [18F]FEMPA, and [18F]PBR111 seem roughly equivalent, with BPND in the range of 2–4 in cortex of healthy HAB subjects. [123I]CLINDE has admirably high BPND,97 and the 13 h physical half of the SPECT radionuclide should favour its widespread use. However, there has been no ‘industry standard’ for the characterization of molecular imaging tracers, and comparison of the merits of tracers remains difficult due to the differing analytical methods and endpoints. This issue may best be resolved through head-to-head comparisons of two tracers; several such reports are available in rodents, but there is so-far only one such comparison of TSPO ligands in humans. In that study, [11C]DPA-713 PET proved to be a more sensitive indicator of age-related increases in TSPO and Alzheimer’s disease pathology than was [11C]-(R)-PK11195,142 consistent with its higher specific binding component. However, we note that the endpoint in that study was a BPND calculated relative to an (idiosyncratic) reference input derived from healthy young subjects. Age or disease-dependent changes in TSPO tracer metabolism or non-specific binding may compromise this approach.

The present synopsis of the TSPO PET literature draws attention to two main deficiencies in the literature, that might be remedied in future studies. First, the wide range of endpoints makes the comparison of TSPO ligands difficult. Second, in the absence of a true non-binding reference region, there is a need to define the non-specific binding component by displacement or graphical analysis. Overall, this review supports five specific recommendations for arriving at a better understanding of the cellular nature of TSPO binding, and for optimal quantitation.

Caution is necessary in the attribution of cerebral TSPO binding exclusively to microglia. The contributions of other glial cell types, vascular endothelium, and blood-derived monocytes to the PET signal in healthy brain or in acute inflammatory conditions should be confirmed by experiment.

For the present, report plasma free fraction of new tracers, despite the absence of compelling evidence that this parameter can bias TSPO binding results. Furthermore, publishing a representative radiochromatogram of plasma extracts for new tracers can aid in the identification of potentially brain-penetrating metabolites.

First-in-human reports should present results of 2TCM analysis. Even if over-specified, the microparameters can inform and constrain efforts to ascertain the specific binding component, i.e. the decomposition of VT into VS and VND.

Since reference tissue methods tend to introduce a bias in the estimation of TSPO binding, confirm the non-specific binding of new ligands by plotting VT as a function of allelic status or by pharmacological displacement.

Assess the fitness of more convenient metrics such as SUV, SUVR, or pseudo-reference tissue analyses for new tracers relative to the known specific binding component.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: a grant from the Wesley Hospital Research Foundation (Funding agreement 2016-19).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

PC contributed to writing and final compilation. All authors wrote sections of the manuscript, and had read and given approval for the final submission.

References

- 1.Estes ML, McAllister AK. Alterations in immune cells and mediators in the brain: it's not always neuroinflammation!. Brain Pathol 2014; 24: 623–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graeber MB. Neuroinflammation: no rose by any other name. Brain Pathol 2014; 24: 620–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu GJ, Middleton RJ, Hatty CR, et al. The 18 kDa translocator protein, microglia and neuroinflammation. Brain Pathol 2014; 24: 631–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svahn AJ, Becker TS, Graeber MB. Emergent properties of microglia. Brain Pathol 2014; 24: 665–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filiou MD, Arefin AS, Moscato P, et al. ‘Neuroinflammation' differs categorically from inflammation: transcriptomes of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia and inflammatory diseases compared. Neurogenetics 2014; 15: 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goverman J. Autoimmune T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9: 393–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Notter T, Coughlin JM, Gschwind T, et al. Translational evaluation of translocator protein as a marker of neuroinflammation in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. Epub ahead of print 17 January 2017. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2016.248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Banati RB, Myers R, Kreutzberg GW. PK (‘peripheral benzodiazepine')-binding sites in the CNS indicate early and discrete brain lesions: microautoradiographic detection of [3H]PK11195 binding to activated microglia. J Neurocytol 1997; 26: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banati RB, Middleton RJ, Chan R, et al. Positron emission tomography and functional characterization of a complete PBR/TSPO knockout. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedersen MD, Minuzzi L, Wirenfeldt M, et al. Up-regulation of PK11195 binding in areas of axonal degeneration coincides with early microglial activation in mouse brain. Eur J Neurosci 2006; 24: 991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandiego CM, Gallezot JD, Pittman B, et al. Imaging robust microglial activation after lipopolysaccharide administration in humans with PET. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112: 12468–12473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavisse S, Guillermier M, Herard AS, et al. Reactive astrocytes overexpress TSPO and are detected by TSPO positron emission tomography imaging. J Neurosci 2012; 32: 10809–10818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Kennedy AM, et al. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. Lancet 2001; 358: 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 388–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banati RB, Newcombe J, Gunn RN, et al. The peripheral benzodiazepine binding site in the brain in multiple sclerosis: quantitative in vivo imaging of microglia as a measure of disease activity. Brain 2000; 123: 2321–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerhard A, Schwarz J, Myers R, et al. Evolution of microglial activation in patients after ischemic stroke: a [11C](R)-PK11195 PET study. NeuroImage 2005; 24: 591–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen B, Vugts DJ, Funke U, et al. Imaging of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis and stroke: recent developments in positron emission tomography. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016; 1862: 425–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pappata S, Levasseur M, Gunn RN, et al. Thalamic microglial activation in ischemic stroke detected in vivo by PET and [11C]PK1195. Neurology 2000; 55: 1052–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gershen LD, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Dustin IH, et al. Neuroinflammation in temporal lobe epilepsy measured using positron emission tomographic imaging of translocator protein. JAMA Neurol 2015; 72: 882–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cagnin A, Myers R, Gunn RN, et al. In vivo visualization of activated glia by [11C] (R)-PK11195-PET following herpes encephalitis reveals projected neuronal damage beyond the primary focal lesion. Brain 2001; 124: 2014–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Minn I, et al. Imaging of glial cell activation and white matter integrity in brains of active and recently retired National Football League players. JAMA Neurol 2017; 74: 67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setiawan E, Wilson AA, Mizrahi R, et al. Role of translocator protein density, a marker of neuroinflammation, in the brain during major depressive episodes. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2011; 35: 804–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banati R, Hickie IB. Therapeutic signposts: using biomarkers to guide better treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Med J Aust 2009; 190: S26–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloomfield PS, Howes OD, Turkheimer F, et al. Response to Narendran and Frankle: The interpretation of PET microglial imaging in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173: 537–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch S. Clinical changes measured by [11C](R)-PK11195 PET in patients with psychosis and cognitive decline are associated with impaired event related potential mismatch negativity. 12th biennial winter workshop on schizophrenia. Davos, Switzerland: Schizophr Res, 2004.

- 27.Narendran R, Frankle WG. Comment on analyses and conclusions of “microglial activity in people at ultra high risk of psychosis and in schizophrenia: an [(11)C]PBR28 PET brain imaging study. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173: 536–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banati RB. Brain plasticity and microglia: is transsynaptic glial activation in the thalamus after limb denervation linked to cortical plasticity and central sensitisation? J Physiol Paris 2002; 96: 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banati RB, Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, et al. Long-term trans-synaptic glial responses in the human thalamus after peripheral nerve injury. Neuroreport 2001; 12: 3439–3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inta D, Lang UE, Borgwardt S, et al. Microglia activation and schizophrenia: lessons from the effects of minocycline on postnatal neurogenesis, neuronal survival and synaptic pruning. Schizophr Bull 2017; 43: 493–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betlazar C, Middleton RJ, Banati RB, et al. The impact of high and low dose ionising radiation on the central nervous system. Redox Biol 2016; 9: 144–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Junck L, Olson JM, Ciliax BJ, et al. PET imaging of human gliomas with ligands for the peripheral benzodiazepine binding site. Ann Neurol 1989; 26: 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banati RB, Goerres GW, Myers R, et al. [11C](R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography imaging of activated microglia in vivo in Rasmussen's encephalitis. Neurology 1999; 53: 2199–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown AK, Fujita M, Fujimura Y, et al. Radiation dosimetry and biodistribution in monkey and man of 11C-PBR28: a PET radioligand to image inflammation. J Nucl Med 2007; 48: 2072–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan Z, Harold D, Pasqualetti G, et al. Can studies of neuroinflammation in a TSPO genetic subgroup (HAB or MAB) be applied to the entire AD cohort? J Nucl Med 2015; 56: 707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braestrup C, Squires RF. Specific benzodiazepine receptors in rat brain characterized by high-affinity (3H)diazepam binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1977; 74: 3805–3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoemaker H, Bliss M, Yamamura HI. Specific high-affinity saturable binding of [3H] R05-4864 to benzodiazepine binding sites in the rat cerebral cortex. Eur J Pharmacol 1981; 71: 173–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Fur G, Perrier ML, Vaucher N, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites: effect of PK 11195, 1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide. I. In vitro studies. Life Sci 1983; 32: 1839–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Besman MJ, Yanagibashi K, Lee TD, et al. Identification of des-(Gly-Ile)-endozepine as an effector of corticotropin-dependent adrenal steroidogenesis: stimulation of cholesterol delivery is mediated by the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989; 86: 4897–4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krueger KE, Papadopoulos V. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors mediate translocation of cholesterol from outer to inner mitochondrial membranes in adrenocortical cells. J Biol Chem 1990; 265: 15015–15022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukhin AG, Papadopoulos V, Costa E, et al. Mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptors regulate steroid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989; 86: 9813–9816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papadopoulos V, Baraldi M, Guilarte TR, et al. Translocator protein (18 kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006; 27: 402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]