Abstract

Objective:

The objective was to determine the effectiveness of real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in adults ≥ 60 years of age with type 1 (T1D) or type 2 (T2D) diabetes using multiple daily insulin injections (MDI).

Methods:

A multicenter, randomized trial was conducted in the United States and Canada in which 116 individuals ≥60 years (mean 67 ± 5 years) with T1D (n = 34) or T2D (n = 82) using MDI therapy were randomly assigned to either CGM (Dexcom™ G4 Platinum CGM System® with software 505; n = 63) or continued management with self-monitoring blood glucose (SMBG; n = 53). Median diabetes duration was 21 (14, 30) years and mean baseline HbA1c was 8.5 ± 0.6%. The primary outcome, HbA1c at 24 weeks, was obtained for 114 (98%) participants.

Results:

HbA1c reduction from baseline to 24 weeks was greater in the CGM group than Control group (−0.9 ± 0.7% versus −0.5 ± 0.7%, adjusted difference in mean change was −0.4 ± 0.1%, P < .001). CGM-measured time >250 mg/dL (P = .006) and glycemic variability (P = .02) were lower in the CGM group. Among the 61 in the CGM group completing the trial, 97% used CGM ≥ 6 days/week in month 6. There were no severe hypoglycemic or diabetic ketoacidosis events in either group.

Conclusion:

In adults ≥ 60 years of age with T1D and T2D using MDI, CGM use was high and associated with improved HbA1c and reduced glycemic variability. Therefore, CGM should be considered for older adults with diabetes using MDI.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, older, CGM, MDI, glucose monitoring, insulin

Numerous studies have demonstrated that persistent use of real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) improves glycemic control1-6 and quality of life7 in individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) and multiple daily insulin injection (MDI) therapy. The benefits of CGM use have also been reported in individuals with T2D who are managed with or without intensive insulin treatment.8-14

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE)/American College of Endocrinology (ACE), American Diabetes Association, Endocrine Society and Joslin Diabetes Center recommend that CGM should be made available to individuals with T1D, T2D individuals treated with intensive insulin regimens, and all patients with diabetes who are at risk for hypoglycemia and/or have hypoglycemia unawareness.15-18

It is well recognized that the risk of severe or fatal hypoglycemia increases exponentially with age in elderly individuals with diabetes who are treated with insulinotropic medications.19-21

Studies have shown that elderly T1D adults have higher rates of hypoglycemia and greater frequency of hypoglycemia unawareness than younger adults with T1D.22,23 A recent observational study by DuBose and colleagues found that approximately one half of older adults with long-standing T1D spend at least 90 minutes per day <70 mg/dL, with a quarter at <70 mg/dL for at least 2.5 hours per day.24

Evidence from a small retrospective study suggests that use of CGM by older T1D adults may reduce the frequency of severe hypoglycemic episodes and improve overall glycemic control;25 however, there are limited data regarding use of stand-alone CGM in older individuals with diabetes using multiple daily injections. The potential to decrease HbA1c and reduce rates of severe hypoglycemia in this population has both significant clinical and financial implications.

We conducted a 24-week randomized multicenter clinical trial (DIAMOND study) that evaluated the effect of CGM on glycemic control in MDI-treated T1D and T2D adults with elevated HbA1c levels. Results from analysis of the T1D and T2D study participants across a large age range (26-79 years) showed that use of CGM compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) resulted in a greater decrease in HbA1c level during 24 weeks.26,27 In this report, we present findings from a subset analysis of the full DIAMOND study population that assessed the effectiveness of CGM use in MDI-treated T1D and T2D individuals ≥60 years of age

Methods

The DIAMOND trial was conducted at 29 endocrinology practices across North America, 27 of which enrolled older adults (21 community-based and 6 academic). The study is listed on www.clinicaltrials.gov, under identifier NCT02282397. The protocol and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant informed consent forms were approved by a central and multiple local institutional review boards. Details of the protocol have been published.26 Key aspects of the protocol are summarized herein.

Study Participants

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Major eligibility criteria for this analysis included age ≥60 years, diagnosis of T1D or T2D being treated with multiple daily injections of insulin for at least one year, central laboratory measured HbA1c 7.5% to 10.0%, stable diabetes medication regimen and weight over the prior 3 months, self-reported blood glucose meter testing averaging 2 or more times per day for T2D and 3 or more for T1D, and estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥45. Major exclusion criteria were use of real-time CGM within 3 months of screening and any medical condition(s) that would make it inappropriate or unsafe to target an HbA1c of <7.0%. This determination was made by investigators.

Study Design

Prior to randomization to either CGM or SMBG (Control), each participant used a CGM device for 2 weeks that recorded glucose concentrations not visible to the participant (referred to as a “blinded” CGM). Participants in both groups were provided with a Contour Next USB meter and test strips (Ascensia Diabetes Care, Parsippany, NJ, USA). Participants in the CGM group were provided with a Dexcom™ G4 Platinum CGM System® with an enhanced algorithm (software 505) (Dexcom, Inc, San Diego, CA), which measures glucose concentrations from interstitial fluid in the range of 40 to 400 mg/dL every 5 minutes. General guidelines were provided to participants about using CGM, and individualized recommendations were made by their clinician about individual goals and incorporating CGM trend information into their diabetes management. CGM was used adjunctive to blood glucose monitoring, according to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling at the time the study was conducted. The Control group was asked to perform home blood glucose monitoring at least 4 times daily. Specific insulin adjustments were not prescriptive in the protocol for either group but instead were at the discretion of treating clinicians at the clinical sites.

Follow-up visits for both treatment groups occurred after 4, 12, and 24 weeks. The CGM group had an additional visit one week after randomization to troubleshoot potential use issues. The Control group had 2 additional visits 1 week prior to the 12 and 24 week visits to initiate blinded CGM use for 1 week. Phone contacts for both groups occurred 2 weeks and 3 weeks after randomization.

HbA1c was measured at baseline, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks at the Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories, University of Washington, Seattle, WA using the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial standardized analyzer (TOSOH, Biosciences, Inc, South San Francisco, CA). Satisfaction with CGM was assessed by completion of the CGM Satisfaction Scale by the CGM group at 24 weeks. The survey consists of 44 items indicating the degree of agreement or disagreement on a 1-5 Likert scale, with 2 subscales referred to as “benefits” and “hassles.”28 Numeracy was assessed using the Diabetes Numeracy Test-15 (DNT-5), a 5-item questionnaire that investigates numeracy skills in individuals with diabetes.29

Severe hypoglycemia (SH) was defined as an event that required assistance from another person to administer carbohydrates or other resuscitative action and diabetic ketoacidosis was defined as an event involving all of the following: symptoms such as polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, or vomiting; serum ketones >1.5 mmol/L or large/moderate urine ketones; either arterial blood pH <7.30 or venous pH <7.24 or serum bicarbonate <15; and treatment provided in a health care facility.

Statistical Methods

The primary outcome was change in the central-laboratory measured HbA1c from baseline to 24 weeks. The primary analysis was a treatment group comparison of the change in HbA1c from baseline to 24 weeks in an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model, adjusted for baseline HbA1c and clinical site as a random effect. Confounding was assessed by repeating the analysis including potential confounding variables as covariates.

CGM data obtained in conjunction with the 12-week and 24-week visits (blinded use in the Control group and unblinded use in the CGM group for approximately 7 days each time) were used to determine the amount of time per day the glucose concentration was hypoglycemic (<60 mg/dL), hyperglycemic (>250 mg/dL), and in the target range of 70 to 180 mg/dL at each visit. Glucose variability was assessed by computing the coefficient of variation (CV). Treatment group comparisons were made on the pooled data from 12 and 24 weeks with ANCOVA models based on ranks using van der Waerden scores if the metric was skewed, adjusted for the corresponding baseline value, baseline HbA1c, and clinical site as a random effect. Frequency of blood glucose self-monitoring was based on meter downloads and compared between groups using ANCOVA, adjusted for the baseline frequency and clinical site as a random effect. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All P values are 2-sided.

Results

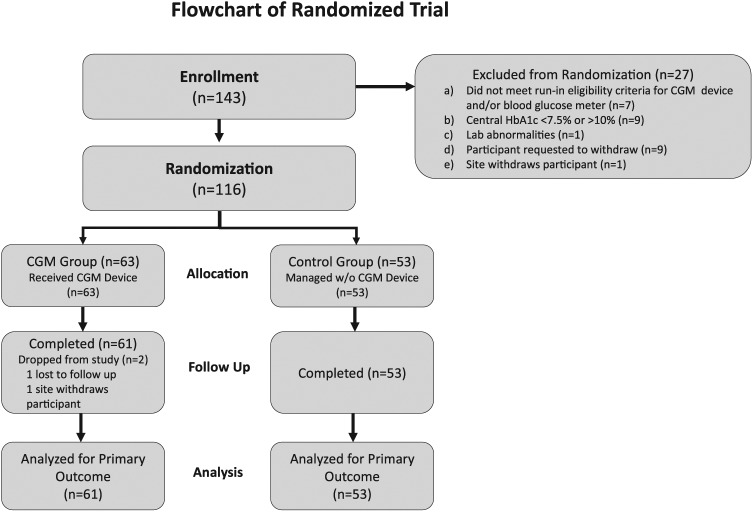

In this analysis, 116 T1D (n = 34) and T2D (n = 82) participants with mean age of 67 ± 5 years were randomly assigned to the CGM group (n = 63) or Control group (n = 53). Median diabetes duration was 21 (14, 30) years and mean baseline HbA1c was 8.5 ± 0.6%. Participant characteristics according to treatment group are presented in Table 1. The groups were well-balanced among education levels and diabetes numeracy. The 24-week primary study outcome visit was completed by 61 (97%) of the CGM group and 53 (100%) of the Control group (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| CGM (n = 63) |

Control (n = 53) |

|

|---|---|---|

| n (%) unless otherwise specified | ||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 67 ± 5 | 67 ± 5 |

| Diabetes duration, years median (quartiles) | 20 (14, 32) | 21 (16, 30) |

| Diabetes type | ||

| Type 1 | 20 (32) | 14 (26) |

| Type 2 | 43 (68) | 39 (74) |

| Local c-peptide levela | ||

| <0.2 ng/mL | 24 (38) | 11 (21) |

| ≥ 0.2 ng/mL | 39 (62) | 42 (79) |

| Female sex | 34 (54) | 26 (49) |

| Race/ethnicityb | ||

| White/non-Hispanic | 43 (68) | 43 (83) |

| Black/non-Hispanic | 6 (10) | 5 (10) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 (11) | 4 (8) |

| Asian | 4 (6) | 0 |

| More than one race | 3 (5) | 0 |

| Highest education* | ||

| <Bachelor’s degree | 30 (48) | 27 (54) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 16 (26) | 13 (26) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 16 (26) | 10 (20) |

| BMI, kg/m2 mean (SD) | 33 ± 7 | 34 ± 8 |

| HbA1c, % mean (SD) | 8.4 ± 0.6 | 8.6 ± 0.7 |

| Self-reported blood glucose monitoring | ||

| <4 times/day | 33 (52) | 28 (53) |

| ≥4 times/day | 30 (48) | 25 (47) |

| Event in previous 12 months | ||

| ≥1 severe hypoglycemia | 3 (5) | 3 (6) |

| ≥1 diabetic ketoacidosis | 0 | 0 |

| Use of noninsulin glucose-lowering medicationc | 31 (49) | 24 (45) |

| Number of long-acting insulin injections per day | ||

| 1 | 44 (70) | 31 (58) |

| 2 | 19 (30) | 21 (40) |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Number of rapid-acting insulin injections per day | ||

| 2 | 1 (2) | 7 (13) |

| 3 | 49 (78) | 35 (66) |

| 4 | 11 (17) | 8 (15) |

| ≥ 5 | 2 (3) | 3 (6) |

| CGM use in past | 8 (13) | 3 (6) |

| % Correct on the Diabetes Numeracy Test mean (SD) | 79 ± 21 | 75 ± 23 |

| Hypoglycemia awarenessd | ||

| Reduced awareness | 11 (17) | 7 (13) |

| Uncertain | 10 (16) | 5 (9) |

| Aware | 42 (67) | 41 (77) |

C-peptide level was measured at local laboratories.

Missing data for CGM group/Control group: 0/1 for race and 1/3 for education.

Noninsulin meds for CGM group/Control group were 24/17 Metformin; 4/2 GLP1; 6/2 DPP4; 5/9 SGLT2; 3/6 other.

Measured with the Clarke Hypoglycemia Unawareness Survey.30

Figure 1.

Participant disposition.

Change in HbA1c and other CGM metrics

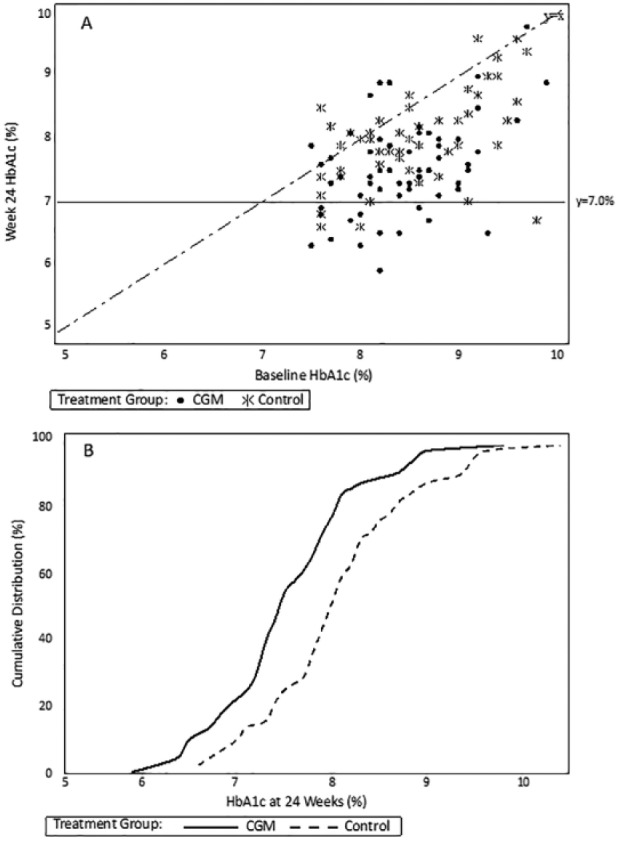

Mean HbA1c, which at baseline was 8.4 ± 0.6% in the CGM group and 8.6 ± 0.7% in the Control group, decreased to 7.5 ± 0.7% and 8.0 ± 0.7%, respectively at 12 weeks with an adjusted difference in mean change in HbA1c of −0.4 ±0.1% (P < .001). At 24 weeks, HbA1c reduction from baseline was greater in the CGM group than Control group (−0.9 ± 0.7% vs −0.5 ± 0.7%) with an adjusted difference in mean change of −0.4 ± 0.1% (P < .001). For each treatment group, baseline and 24-week HbA1c values for each participant relative to American Diabetes Association targets are shown in Figure 2A, and the cumulative distribution of the 24-week HbA1c values is shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

HbA1c values at baseline and 24 weeks, by group. (A) Scatterplot of 24-week HbA1c levels by baseline HbA1c level. The horizontal line at 7.0% represents the American Diabetes Association HbA1c goal for nonpregnant adults with diabetes. Points below the diagonal line represent cases in which the 24-week HbA1c level was lower than the baseline HbA1c level, points above the diagonal line represent cases in which the 24-week HbA1c level was higher than the baseline HbA1c level, and points on the diagonal line represent cases in which the 24-week and baseline HbA1c values were the same. (B) Cumulative distribution of 24-week HbA1c values. For any given 24-week HbA1c level, the percentage of cases in each treatment group with an HbA1c value at that level or lower can be determined from the figure.

Significant between-group differences in improvements in CGM-measured mean glucose, glycemic variation (CV) and in the average time within glucose range (70-180 mg/dL) and in hyperglycemia (>250 mg/dL) at 24 weeks were observed; however, there was minimal hypoglycemia at baseline in both the CGM and Control groups (median time <60 mg/dL was 10 vs 8 minutes/day, respectively), which affected the ability to detect a difference in hypoglycemia (Table 2).

Table 2.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring Outcomes.

| CGM |

Control |

P valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 63) | 12 weeks (n = 61)a | 24 weeks (n = 58)a | Baseline (n = 53) | 12 weeks (n = 52)a | 24 weeks (n = 50)a | ||

| Mean glucose, mg/dL | 175 ± 25 | 167 ± 27 | 168 ± 29 | 179 ± 30 | 178 ± 28 | 180 ± 28 | .01 |

| Glycemic variability, coefficient of variation % | 34 (28, 42) | 33 (28, 37) | 31 (28, 36) | 34 (29, 38) | 33 (28, 38) | 33 (27, 39) | .02 |

| Time spent: 70-180 mg/dL, min/day | 796 ± 236 | 892 ± 256 | 889 ± 251 | 753 ± 253 | 767 ± 265 | 732 ± 252 | <.001 |

| Time spent: >250 mg/dL, min/day | 172 (83, 281) | 93 (30, 180) | 89 (37, 208) | 208 (112, 294) | 180 (81, 251) | 179 (83, 316) | .006 |

| Time spent: <60 mg/dL, min/day | 10 (1, 38) | 4 (0, 15) | 3 (0, 15) | 8 (1, 23) | 4 (0, 27) | 4 (0, 24) | .11 |

Median (IQR) is reported for glycemic variability and for time in the hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges. Mean ± SD is reported for mean glucose and time in range.

CGM metrics were not calculated for participants with <72hrs of data: 1 CGM/1 Control at 12 weeks; 3 CGM/3 Control at 24 weeks.

P values are from analysis of covariance models adjusted for the corresponding baseline value, baseline HbA1c, and clinical site as a random effect using pooled data from 12 and 24 weeks. Due to skewed distributions, the models for glycemic variability and time in the hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic ranges were based on ranks using van der Waerden scores.

Glucose Monitoring

Among the 61 CGM participants completing the trial, mean CGM use was 6.9 ± 0.2 days/week in month one (weeks 1-4); and 6.8 ± 1.1 in month 6 (weeks 21-24); 97% used CGM ≥ 6 days/week in month 6. The mean reduction in the number of daily blood glucose tests from baseline to week 24 was significantly greater for the CGM group compared with the Control group (−1.2 ± 1.6 vs −0.2 ± 1.4, P = .001).

CGM Satisfaction

In the CGM group, satisfaction with use of CGM was high as indicated by the mean score of 4.2 ± 0.4 on the CGM Satisfaction Survey (possible score range 1 to 5), with mean scores of 4.3 ± 0.5 on the Benefits subscale and 1.8 ± 0.5 on the Hassles subscale, indicating that perceived benefits were high while perceived hassles were few (Table 3).

Table 3.

CGM Satisfaction Questionnaire at 24 Weeks (n = 60 Participants in the CGM group), 44 Items on How Satisfied the Participant Is With Using CGM, Scale 1-5.

| Mean score | Agree strongly (%) | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | Disagree strongly (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using the continuous glucose monitor . . . | ||||||

| 1. Causes me to be more worried about controlling blood sugars. | 3.3 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 18 | 33 |

| 2. ►Makes adjusting insulin easier. | 4.4 | 52 | 40 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| 3. ►Helps me to be sure about making diabetes decisions. | 4.4 | 52 | 38 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| 4. Causes others to ask too many questions about diabetes. | 3.7 | 5 | 12 | 20 | 35 | 28 |

| 5. Makes me think about diabetes too much. | 3.7 | 2 | 13 | 22 | 37 | 25 |

| 6. ►Helps to keep low blood sugars from happening. | 4.4 | 53 | 32 | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| 7. ►Has taught me new things about diabetes that I didn’t know before. | 4.4 | 52 | 38 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 8. Causes too many hassles in daily life. | 4.2 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 35 | 45 |

| 9. ►Teaches me how eating affects blood sugar. | 4.5 | 58 | 37 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 10. ►Helps me to relax, knowing that unwanted changes in blood sugar will be detected quickly. | 4.4 | 50 | 40 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. ►Has helped me to learn about how exercise affects blood sugar. | 4.2 | 38 | 43 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 12. ►Helps with keeping diabetes under control on sick days. | 4.1 | 32 | 45 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| 13. ►Has shown me that blood sugar is predictable and orderly. | 3.5 | 22 | 42 | 12 | 17 | 8 |

| 14. Sometimes gives too much information to work with. | 3.9 | 2 | 8 | 13 | 52 | 25 |

| 15. ►Has made it easier to accept doing blood sugar tests. | 4.1 | 37 | 40 | 15 | 3 | 2 |

| 16. Is uncomfortable or painful. | 4.2 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 40 | 43 |

| 17. ►Has helped me to learn how to treat low sugars better. | 4.2 | 47 | 32 | 17 | 5 | 0 |

| 18. Is more trouble than it is worth. | 4.5 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 27 | 65 |

| 19. ►Has helped my family to get along better about diabetes. | 3.9 | 28 | 37 | 30 | 3 | 2 |

| 20. ►Shows patterns in blood sugars that we didn’t see before. | 4.4 | 47 | 50 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 21. ►Helps prevent problems rather than fixing them after they’ve happened. | 4.4 | 48 | 45 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| 22. ►Allows more freedom in daily life. | 4.1 | 37 | 43 | 15 | 5 | 0 |

| 23. ►Makes it clearer how some everyday habits affect blood sugar levels. | 4.4 | 45 | 50 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 24. ►Makes it easier to complete other diabetes self-care duties. | 4.2 | 33 | 50 | 15 | 2 | 0 |

| 25. Has caused more family arguments. | 4.4 | 0 | 7 | 10 | 23 | 60 |

| 26. Is too hard to get it to work right. | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 45 | 45 |

| 27. Has been harder or more complicated than expected. | 4.3 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 38 | 48 |

| 28. ►Has helped to control diabetes better even when not wearing it. | 3.5 | 13 | 43 | 28 | 10 | 5 |

| 29. Causes our family to talk about blood sugars too much. | 4.0 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 47 | 28 |

| 30. Makes it harder for me to sleep. | 4.2 | 2 | 5 | 13 | 33 | 47 |

| 31. Causes more embarrassment about feeling different from others. | 4.5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 38 | 57 |

| 32. Shows more “glitches” and “bugs” than it should. | 4.1 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 45 | 37 |

| 33. Interferes a lot with sports, outdoor activities, etc. | 4.3 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 50 | 38 |

| 34. Skips too many readings to be useful. | 4.4 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 45 | 48 |

| 35. Gives a lot of results that don’t make sense. | 4.2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 52 | 37 |

| 36. Causes too many interruptions during the day. | 4.4 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 45 | 50 |

| 37. Alarms too often for no good reason. | 4.3 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 48 | 42 |

| 38. ►Has helped to adjust pre-meal insulin doses. | 4.2 | 38 | 45 | 13 | 3 | 0 |

| 39. The feedback from the device is not easy to understand or useful. | 4.2 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 48 | 38 |

| 40. I don’t recommend this for others with diabetes. | 4.7 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 20 | 77 |

| 41. ►Has made me worry less about having low blood sugars. | 4.2 | 43 | 37 | 15 | 3 | 2 |

| 42. ►If possible, I want to use this device when the research study is over. | 4.5 | 65 | 27 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| 43. ►Helps in adjusting doses of insulin needed through the night. | 4.2 | 38 | 47 | 13 | 2 | 0 |

| 44. ►Makes me feel safer knowing that I will be warned about low blood sugar before it happens. | 4.6 | 68 | 27 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

Overall mean ± SD score 4.2 ± 0.4. Benefits subscale mean ± SD score 4.3 ± 0.5 (items 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 38, 41, 42, 43, 44). Hassles subscale mean ± SD score 1.8 ± 0.5 (items 4, 5, 8, 14, 16, 18, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40). One participant did not complete the questionnaire at the conclusion of the study. Responses were missing from 1 participant for items 3, 5, 6, 12, 26, 29, 37, and 39 and missing from 2 participants for item 15. Items with a ► symbol are positively worded (agreeing corresponds to more satisfaction) and those without the symbol are negatively worded (agreeing corresponds to less satisfaction). To calculate the mean value for each item and the overall mean value, the scores for the positively worded items were reversed so that a higher score always corresponds to greater satisfaction. For example, a value of 5 corresponds to “agree strongly” with a positively worded item, or “disagree strongly” with a negatively worded item. To calculate the subscale mean values, scores for all questions were reversed so that a higher score on the Benefits subscale denotes greater satisfaction and a higher score on the Hassles subscale denotes less satisfaction.

Adverse Events

There were no SH or diabetic ketoacidosis events in either group.

Discussion

In this analysis of T1D and T2D individuals ≥60 years old treated with MDI therapy, improvement in HbA1c at 24 weeks was significantly greater in participants using real-time CGM than in the Control group using a blood glucose meter alone for glucose monitoring. The greater HbA1c improvement in the CGM group was reflected in significantly reduced time in CGM-measured time above 250 mg/dL (P = .006) and less glycemic variability (P = .02). Although no cases of SH occurred in either group, the trial’s ability to assess the benefit of CGM on reducing hypoglycemia was limited due to the minimal amount of hypoglycemia recorded at baseline. Nevertheless, the minimal hypoglycemia among CGM participants throughout the study is notable given significant improvement in HbA1c and glycemic variability despite the reduction in daily blood glucose testing observed relative to the Control group.

One surprising finding from the study was the sustained use of CGM. In view of the limited number of prior studies of CGM in older individuals with diabetes, it was unknown if seniors would demonstrate sustained daily use of CGM over 6 months. Among the 61 in the CGM group completing the trial, 97% used CGM ≥6 days/week in month 6. This persistence in CGM use is also reflected in participants’ responses to the CGM Satisfaction Survey at the end of the trial, which indicated very high satisfaction with CGM. This likely contributed to the very high frequency of use, particularly since the protocol had only one visit after week 4 and no scheduled visits or phone contacts between 12 weeks and 24 weeks.

The strengths of this randomized trial included very high treatment adherence and participant retention, a protocol and study processes that can be replicated in real-world clinical practice and central-laboratory measurement of HbA1c. With participation in the trial by both community-based and academic sites and broad eligibility criteria, the trial results should be generalizable to most patients with MDI-treated T1D and T2D who are ≥60 years with HbA1c 7.5% to 9.9%. The study population also was well-matched with the current insulin-using Medicare population. Data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services show that approximately 65.9% of beneficiaries are treated with prandial insulin (including premixed insulins) with or without basal insulin.31 Moreover, our findings are consistent with other studies. A recent retrospective study by Argento and colleague found that use of CGM in older diabetes patients resulted in significant and durable improvement in HbA1c (−0.5%) and reductions in both the percentage of patients reporting severe hypoglycemic (SH) episodes and the frequency of SH per patient despite a lower baseline HbA1c (7.6%)25 than observed in our cohorts (8.5%). Polonsky and colleagues recently surveyed 285 elderly T1D (n = 260) and T2D (n = 25) individuals who were either currently using CGM (n = 210) or hoped to acquire a CGM device for their self-management.32 Current users reported significantly fewer moderate and severe hypoglycemic episodes over the previous 6 months than nonusers as well as significantly greater reductions in hypoglycemic events requiring the assistance of another, emergency room visits and paramedic visits to the home. In other studies, CGM users also reported having a significantly higher quality of life than nonusers.1-14,26

As discussed earlier, hypoglycemia is particularly common in older individuals with diabetes.22-24 Although current guidelines suggest higher HbA1c goals for this population,16 less stringent glycemic control will do little to prevent severe hypoglycemia due to the high prevalence (45%) of hypoglycemia unawareness among these individuals.23

A potential limitation is that this study did not address the question of whether CGM would reduce severe hypoglycemia events in the vulnerable population. The DIAMOND study was designed and powered to investigate whether CGM use would reduce HbA1c.

Conclusions

This randomized trial demonstrates that real-time CGM can be beneficial for elderly adults with T1D and T2D treated with basal-bolus insulin therapy, as has been shown in prior studies in younger adults with diabetes. A high percentage of the study participants used CGM on a daily or near-daily basis over 6 months with a limited number of visits and phone contacts (none after 3 months). CGM use was associated with a high degree of patient satisfaction, reduction in HbA1c, hyperglycemia and glycemic variability and an increase in time in glucose range. Given these significant benefits, CGM should be considered for older adults with diabetes using MDI.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; MDI, multiple daily insulin injections; SH, severe hypoglycemia; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: One author (CG) is employed by Dexcom and CP received consulting fees from Dexcom. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dexcom, Inc, San Diego, CA: David Price; Eileen Casal; Claudia Graham. Dexcom, Inc provided funding for the trial to each of the investigator’s institutions. Additional financial disclosures are as follows: Andrew Ahmann reports consulting from Dexcom, Inc as well as grants from Medtronic and T1D Exchange, grants and consulting from Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, and consulting from Lilly and AstraZeneca. Roy Beck reports that his institution has received supplies for research studies from Dexcom, Inc and Abbott Diabetes Care. Ronnie Aronson reports grants from Sanofi, Takeda, BD, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Merck, Janssen, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Regeneron, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Abbott, Quintiles, ICON, and Medpace, and consulting from Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Sanofi, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Takeda, and Amgen. Richard Bergenstal sits on the advisory board for Abbott Diabetes Care, AstraZeneca, Becton Dickinson, Boehringer Ingelheim, Calibra, Eli Lilly, Hygieia, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi, Takeda, and ResMed; in addition, Dr. Bergenstal holds stock in Merck. Davida Kruger is an advisor, CME speaker, and stock holder for Dexcom, Inc; she also advises and speaks for Abbott Diabetes Care and Animas. Janet McGill reports grant funding from Novartis, Lexicon, and Dexcom as well as consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Dexcom, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, and Calibra. William Polonsky reports personal fees from Dexcom, Inc. David Price is an employee of Dexcom, Inc and is a stock holder. Stephen Aronoff, Stacie Haller, Craig Kollman, Tonya Riddlesworth, Katrina Ruedy, and Elena Toschi have nothing to report.

Participating Clinical Sites: Personnel are listed as (I) for study investigator and (C) for study coordinator. The number of randomized participants is noted in parentheses preceded by the site location and site name. Diabetes & Glandular Disease Clinic, San Antonio, TX (16): Mark Kipnes (I); Stacie Haller (C); Terri Ryan (C) Rocky Mountain Diabetes and Osteoporosis Center, Idaho Falls, ID (9): David Liljenquist (I); Heather Judge (C); Jean Halford (C) Research Institute of Dallas, Dallas, TX (8): Stephen Aronoff (I); Satanya Brooks (C); Gloria Martinez (C); Angela Mendez (C); Theresa Dunnam (C) Henry Ford Medical Center Division of Endocrinology, Detroit, MI (8): Davida Kruger (I); Shiri Levy (I); Arti Bhan (I); Terra Cushman (C); Heather Remtema (C) International Diabetes Center – HealthPartners Institute, Minneapolis, MN (8): Richard Bergenstal (I); Marcia Madden (I); Kathleen McCann (C); Arlene Monk (C), Char Ashanti (C) Joslin Diabetes Center, Boston, MA (7): Elena Toschi (I); Howard Wolpert (I); Astrid Atakov-Castillo (C); Edvina Markovic (C) Accent Clinical Trials, Las Vegas, NV (6): Quang Nguyen (I); Alejandra Martinez (C); Cathy Duran (C) LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology—Barrie, Barrie, ON (6): Hani Alasaad (I); Suzan Abdel-Salam (I); Katherine Buckley (C); Laura Pidgen (C); Lydia Frost (C) Mountain Diabetes and Endocrine Center, Asheville, NC (5): Wendy Lane (I); Stephen Weinrib (I); Kaitlin Ramsey (C); Lynley Farmer (C); Mindy Buford (C) Atlanta Diabetes Associates, Atlanta, GA (5): Bruce Bode (I); Jennifer Boyd (I); Joseph Johnson (I); Nitin Rastogi (C); Katherine Lindmark (C) LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology—Bayview, Toronto, ON (5): Ronnie Aronson (I); Jana Nathan (C) East Coast Institute for Research, LLC, Jacksonville, FL (4): Scott Segel (I); David Sutton (I); Miguel Roura (I); Rebecca Rosenwasser (C); Arnetta Backus (C); Jennifer McElveen (C); Emily Knisely (C); Anne Johnson (C) Advanced Research Institute, Ogden, UT (4): Jack Wahlen (I); Jon Winkfield (I); Hilary Wahlen (C); Emily Hepworth (C); David Winkfield (C); Sue Owens (C) LMC Diabetes & Endocrinology—Thornhill, Thornhill, ON (3): Ronald Goldenberg (I); Sarah Birch (C); Danielle Porplycia (C) Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR (3): Andrew Ahmann (I); Bethany Klopfenstein (I); Farahnaz Joarder (I); Kathy Hanavan (I); Jessica Castle (I); Diana Aby-Daniel (I); Victoria Morimoto (I); Donald DeFrang (C); Bethany Wollam (C) Iowa Diabetes & Endocrinology Research Center, Des Moines, IA (2): Anuj Bhargava (I); Kathy Fitzgerald (I); Diana Wright (I); Teck Khoo (I); Pierre Theuma (I); Tara Herrold (C); Debra Thomsen (C) Amarillo Medical Specialists LLP, Amarillo, TX (2): William Biggs (I); Lorena Sandoval (C); Robin Eifert (C); Becky Cota (C) NorthShore University HealthSystem, Skokie, IL (2): Liana K. Billings (I); Cheryl Auston (C); Janet Yoo (C) Portland Diabetes & Endocrinology Center, Portland, OR (2): Fawn Wolf (I); James Neifing (I); Jennifer Murdoch (I); Susan Staat (C); Tamara Mayfield (C) Diabetes & Endocrine Associates PC, Omaha, NE (2): Sarah Konigsberg (I); Jennifer Rahman (C) Laureate Medical Group at Northside, LLC, Atlanta, GA (2): Kate Wheeler (I); Jennifer Kane (C); Terri Eubanks (C) Barnes Jewish Hospital, Washington University, St. Louis, MO (2): Janet McGill (I); Olivia Jordan (C); Carol Recklein (C) Granger Medical Clinic, West Valley, UT (1): Michelle Litchman (I); Kim Martin (C); Heather Holtman (C); Carrie Briscoe (C) Endocrine Research Solutions, Inc, Roswell, GA (1): John H. Reed (I); Tabby Sapp (C); Jessica Tapia (C) Columbus Regional Research Institute, Endocrine Consultants PC, Columbus, GA (1): Steven Leichter (I); Emily Evans (C) Marin Endocrine Care & Research Inc, Greenbrae, CA (1): Linda Gaudiani (I); Natalie Woods (C); Jesse Cardozo (C) Coastal Metabolic Research Centre, Ventura, CA (1): Roald Chochinov (I); Graciela Hernandez (I); Gabriel Garcia (C); Jessica Rios-Santiago (C).

Quality of Life Collaborator: University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA: William Polonsky.

Coordinating Center: Jaeb Center for Health Research, Tampa, FL: Katrina Ruedy, Roy W. Beck, Craig Kollman, Tonya Riddlesworth, Thomas Mouse.

References

- 1. Pickup JC, Freeman SC, Sutton AJ. Glycaemic control in type 1 diabetes during real time continuous glucose monitoring compared with self monitoring of blood glucose: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials using individual patient data. BMJ. 2011;343:d3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Battelino T, Phillip M, Bratina N, Nimri R, Oskarsson P, Bolinder J. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):795-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in a clinical care environment: evidence from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation continuous glucose monitoring (JDRF-CGM) trial. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):17-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weiss R, Garg SK, Bode BW, et al. Hypoglycemia reduction and changes in hemoglobin A1c in the ASPIRE In-Home Study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(8):542-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yeh HC, Brown TT, Maruthur N, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of methods of insulin delivery and glucose monitoring for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(5):336-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garg SK, Voelmle MK, Beatson CR, et al. Use of continuous glucose monitoring in subjects with type 1 diabetes on multiple daily injections versus continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion therapy: a prospective 6-month study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(3):574-579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hommel E, Olsen B, Battelino T, et al. Impact of continuous glucose monitoring on quality of life, treatment satisfaction, and use of medical care resources: analyses from the SWITCH study. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51(5):845-851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poolsup N, Suksomboon N, Kyaw AM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) on glucose control in diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ehrhardt NM, Chellappa M, Walker MS, Fonda SJ, Vigersky RA. The effect of real-time continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2011;5(3):668-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vigersky RA, Fonda SJ, Chellappa M, Walker MS, Ehrhardt NM. Short- and long-term effects of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):32-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoo HJ, An HG, Park SY, et al. Use of a real time continuous glucose monitoring system as a motivational device for poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;82(1):73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fonda SJ, Graham C, Munakata J, Powers JM, Price D, Vigersky RA. The cost-effectiveness of real-time continuous glucose monitoring (RT-CGM) in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016; 10(4):898-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pettus J, Edelman SV. Differences in use of glucose rate of change (ROC) arrows to adjust insulin therapy among individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes who use continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10(5): 1087-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cox DJ, Taylor AG, Moncrief M, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in the self-management of type 2 diabetes: a paradigm shift. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(5):e71-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bailey TS, Grunberger G, Bode BW, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology 2016 Outpatient Glucose Monitoring Consensus Statement. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(2):231-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2017. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(suppl 1):S1-S135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Klonoff DC, Buckingham B, Christiansen JS, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):2968-2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joslin E, Gray H, Root H. Insulin in hospital and home. J Metab Res. 1922;2:651-699. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meneilly GS, Cheung E, Tuokko H. Counterregulatory hormone responses to hypoglycemia in the elderly patient with diabetes. Diabetes. 1994;43(3):403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meneilly GS, Tessier D. Diabetes in the elderly. Diabet Med. 1995;12(11):949-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schutt M, Fach EM, Seufert J, et al. Multiple complications and frequent severe hypoglycaemia in “elderly” and “old” patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29(8):e176-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weinstock RS, Xing D, Maahs DM, et al. Severe hypoglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 diabetes: results from the T1D Exchange clinic registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8):3411-3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weinstock RS, DuBose SN, Bergenstal RM, et al. Risk factors associated with severe hypoglycemia in older adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(4):603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DuBose SN, Weinstock RS, Beck RW, et al. Hypoglycemia in older adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(12):765-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Argento NB, Nakamura K. Personal real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients 65 years and older. Endocr Pract. 2014;20(12):1297-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beck RW, Riddlesworth T, Ruedy K, et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: The DIAMOND Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317(4):371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bergenstal R, Riddlesworth T, Ruedy K, Kollman C, Price D, Beck RW. Patients with type 2 diabetes using multiple daily insulin injections have high adherence and benefit from CGM: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Paper presented at: 10th International Conference on Advanced Technology and Therapeutics (ATTD); February 15-18, 2017; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study Group. Validation of measures of satisfaction with and impact of continuous and conventional glucose monitoring Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12(9):679-684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zaugg SD, Dogbey G, Collins K, et al. Diabetes numeracy and blood glucose control: association with type of diabetes and source of care. Clin Diabetes. 2014;32(4):152-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clarke WL, Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick LA, Julian D, Schlundt D, Polonsky W. Reduced awareness of hypoglycemia in adults with IDDM. A prospective study of hypoglycemic frequency and associated symptoms. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(4):517-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Puckrein GA, Nunlee-Bland G, Zangeneh F, et al. Impact of CMS Competitive Bidding Program on Medicare beneficiary safety and access to diabetes testing supplies: a retrospective, longitudinal analysis. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(4):563-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Polonsky WH, Peters AL, Hessler D. The impact of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in patients 65 years and older. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10(4):892-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]