Abstract

The TGFβ pathway plays an essential role in embryonic development, organ homeostasis, tissue repair, and disease1,2. This diversity of tasks is achieved through the intracellular effector SMAD2/3, whose canonical function is to control activity of target genes by interacting with transcriptional regulators3. Nevertheless, a complete description of the factors interacting with SMAD2/3 in any given cell type is still lacking. Here we address this limitation by describing the interactome of SMAD2/3 in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). This analysis reveals that SMAD2/3 is involved in multiple molecular processes in addition to its role in transcription. In particular, we identify a functional interaction with the METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex, which deposits N6-methyladenosine (m6A)4. We uncover that SMAD2/3 promotes binding of the m6A methyltransferase complex onto a subset of transcripts involved in early cell fate decisions. This mechanism destabilizes specific SMAD2/3 transcriptional targets, including the pluripotency factor NANOG, thereby poising them for rapid downregulation upon differentiation to enable timely exit from pluripotency. Collectively, these findings reveal the mechanism by which extracellular signalling can induce rapid cellular responses through regulations of the epitranscriptome. These novel aspects of TGFβ signalling could have far-reaching implications in many other cell types and in diseases such as cancer5.

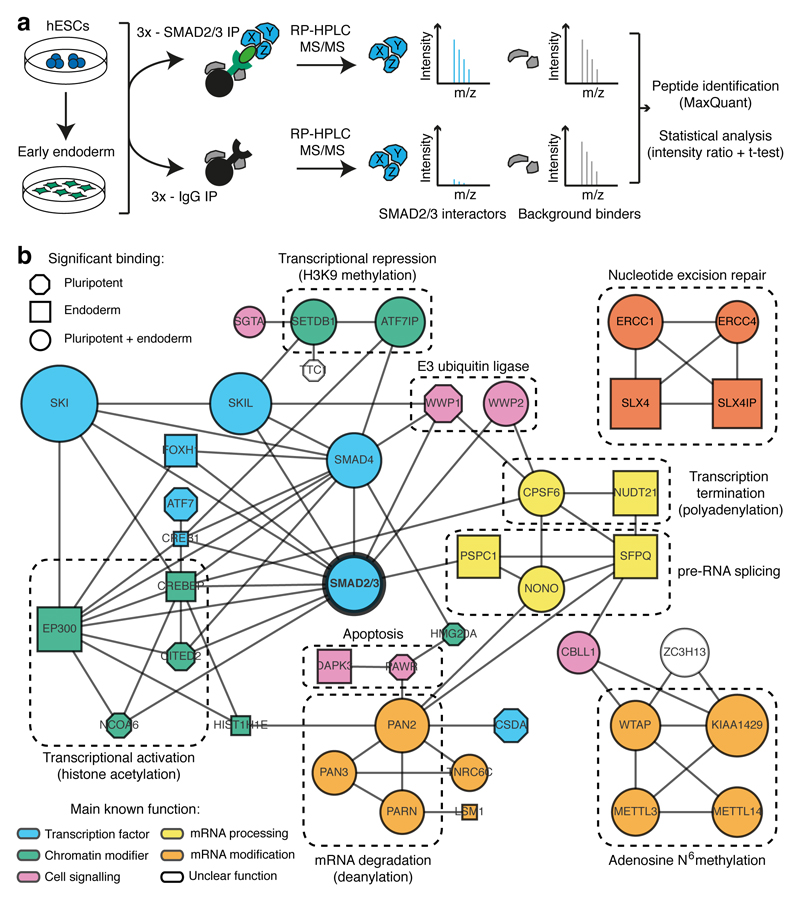

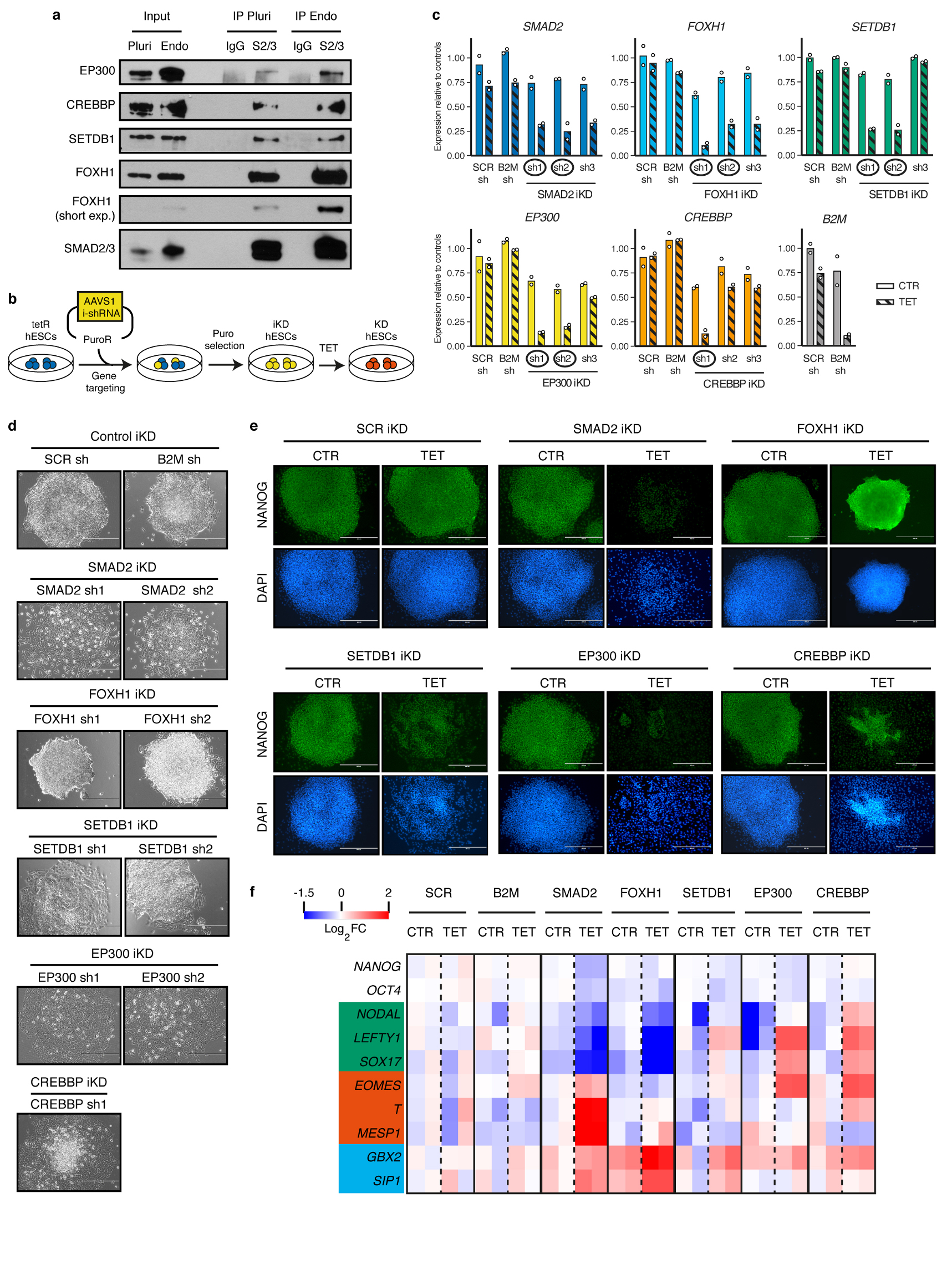

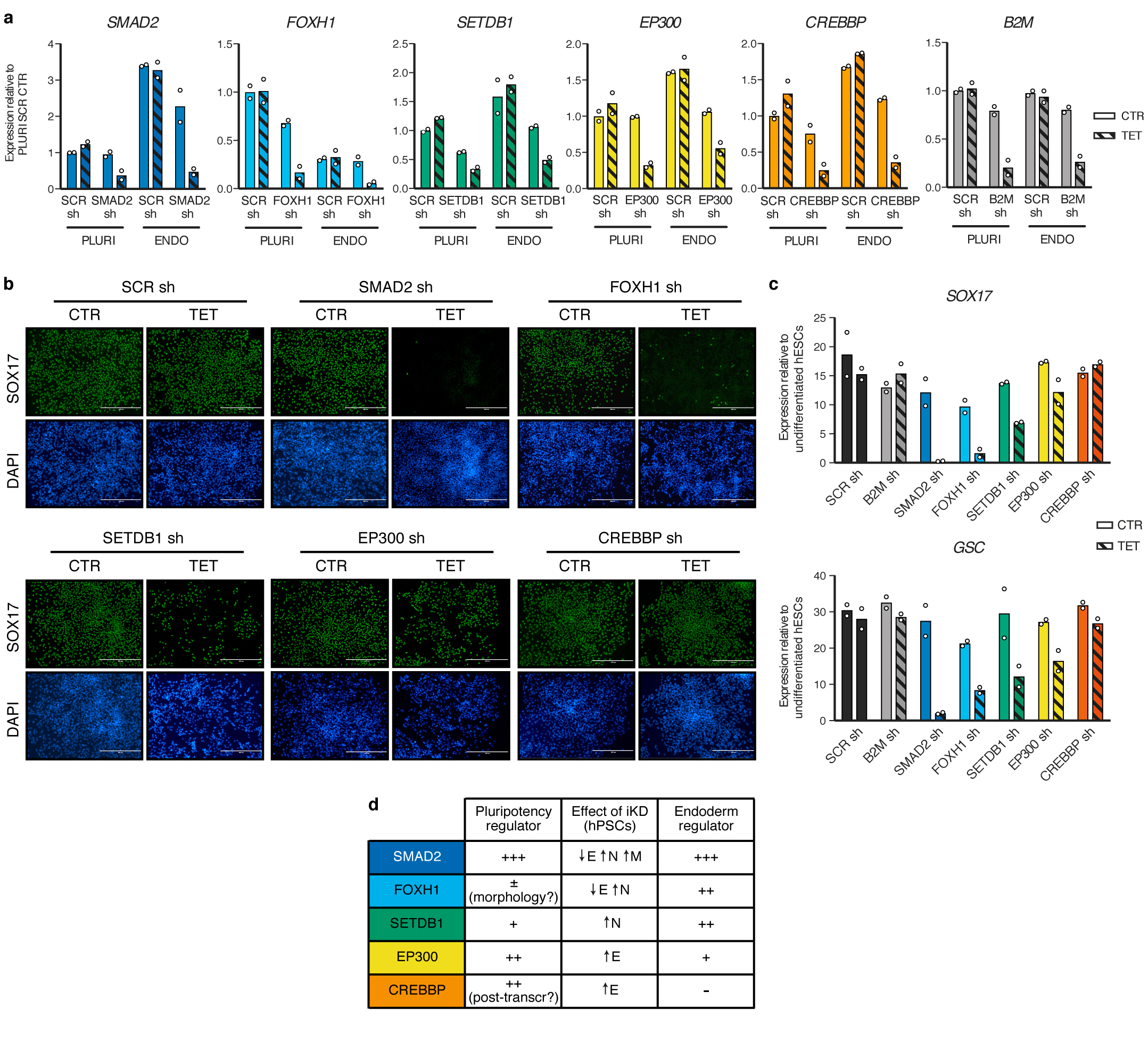

Activin and Nodal, two members of the TGFβ superfamily, play essential roles in cell fate decision in hPSCs6–8. Activin/Nodal signalling is necessary to maintain pluripotency, and its inhibition drives differentiation toward the neuroectoderm lineage6,9,10. Activin/Nodal also cooperates with BMP and WNT to drive mesendoderm specification11–14. Thus, we used hPSC differentiation into definitive endoderm as a model system to interrogate the SMAD2/3 interactome during a dynamic cellular process. For that we developed an optimized SMAD2/3 co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) protocol compatible with mass-spectrometry analyses (Extended Data Fig. 1a-b and Supplementary Discussion). This method allowed a comprehensive and unbiased examination of the proteins interacting with SMAD2/3 for the first time in any given cell type. By examining human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and hESCs induced to differentiate towards endoderm (Fig. 1a), we identified 89 SMAD2/3 partners (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1c-d, and Supplementary Table 1). Of these, only 11 factors were not shared between hESCs and endoderm differentiating cells (Extended Data Fig. 1e), suggesting that the SMAD2/3 interactome is largely conserved across these two lineages (Supplementary Discussion). Importantly, this list included known SMAD2/3 transcriptional and epigenetic cofactors (including FOXH1, SMAD4, SNON, SKI, EP300, SETDB1, and CREBBP3), which validated our method. Furthermore, we performed functional experiments on FOXH1, EP300, CREBBP, and SETDB1, which uncovered the essential function of these SMAD2/3 transcriptional and epigenetic cofactors in hPSC fate decisions (Extended Data Fig. 2 and 3, and Supplementary Discussion).

Figure 1. Identification of the SMAD2/3 interactome.

(a) Experimental approach. (b) Interaction network from all known protein-protein interactions between selected SMAD2/3 partners identified in pluripotent and endoderm cells (n=3 co-IPs; one-tailed t-test: permutation-based FDR<0.05). Nodes describe: (1) the lineage in which the proteins were significantly enriched (shape); (2) significance of the enrichment (size is proportional to the maximum -log p-value); (3) function of the factors (colour). Complexes of interest are marked.

Interestingly, our proteomic experiments also revealed that SMAD2/3 interacts with complexes involved in functions that have never been associated with TGFβ signalling (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1f), such as ERCC1-XPF (DNA repair) and DAPK3-PAWR (apoptosis). Most notably, we identified several factors involved in mRNA processing, modification, and degradation (Fig. 1b), such as the METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex (deposition of N6-methyladenosine, or m6A), the PABP-dependent poly(A) nuclease complex hPAN (mRNA decay), the cleavage factor complex CFIm (pre-mRNA 3’ end processing), and the NONO-SFPQ-PSPC1 factors (RNA splicing and nuclear retention of defective RNAs). Overall, these results suggest that SMAD2/3 could be involved in a large number of biological processes in hPSCs, which include not only transcriptional and epigenetic regulations, but also novel “non-canonical” molecular functions.

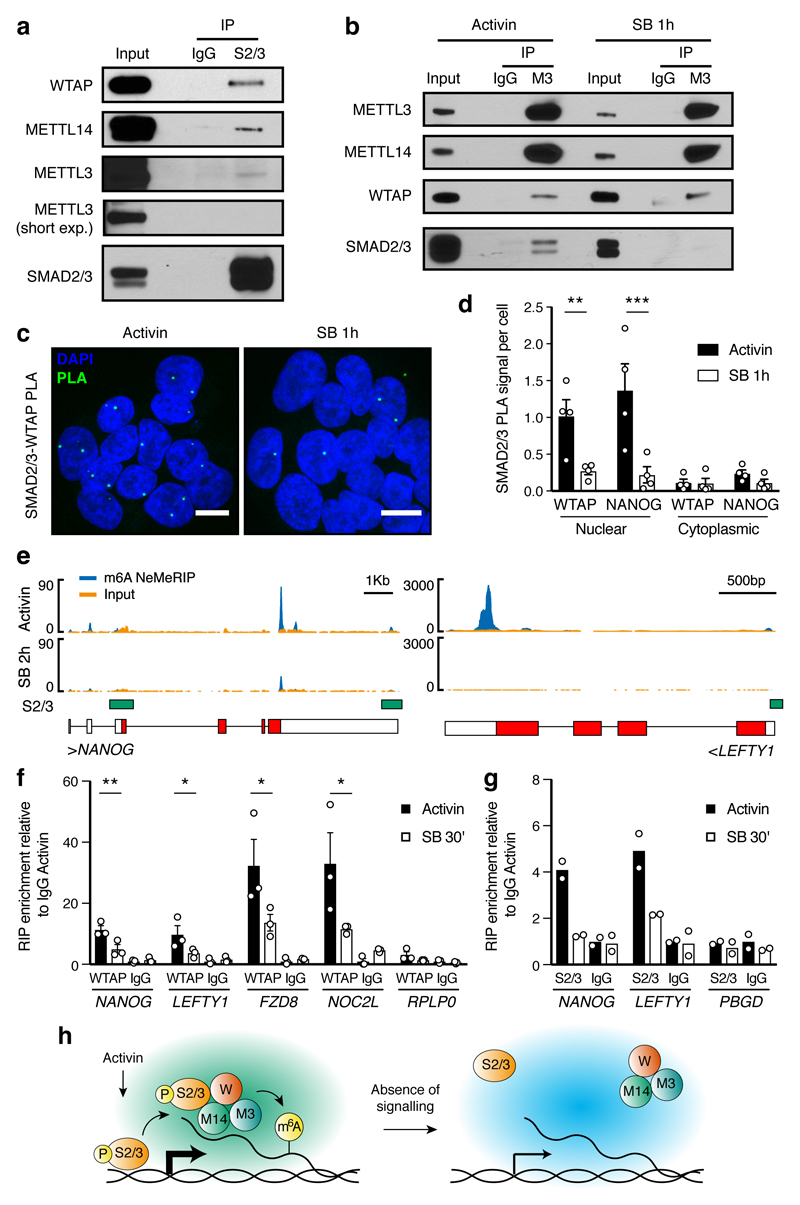

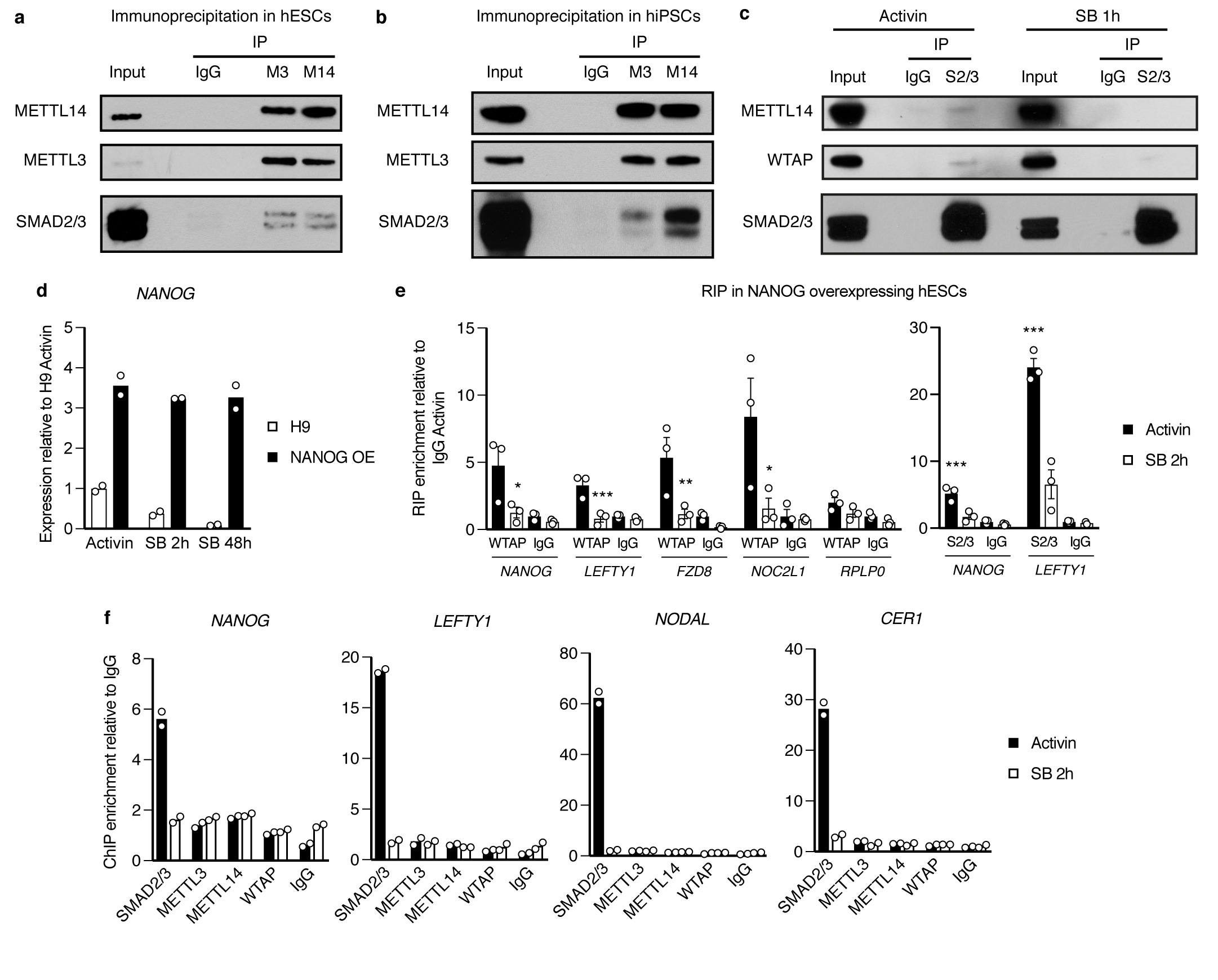

To further explore this hypothesis, we investigated the interplays between Activin/Nodal and m6A deposition. m6A is the most common RNA modification, regulating multiple aspects of mRNA biology including decay and translation4,15–19. However, whether this is a dynamic event that can be modulated by extracellular cues remains to be established. Furthermore, while m6A is known to regulate hematopoietic stem cells20,21 and the transition between the naïve and primed pluripotency states22,23, its function in hPSCs and during germ layer specification is unclear. We first validated the interaction of SMAD2/3 with METTL3-METTL14-WTAP using co-IP followed by Western Blot in both hESCs and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs; Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 4a-b). Interestingly, inhibition of SMAD2/3 phosphorylation blocked this interaction (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 4c). Proximity ligation assays (PLA) also demonstrated that the interaction occurs at the nuclear level (Fig. 2c-d). These observations suggest that SMAD2/3 and the m6A methyltransferase complex interact in an Activin/Nodal signalling-dependent fashion.

Figure 2. Activin/Nodal signalling promotes m6A deposition on specific regulators of pluripotency and differentiation.

(a-b) Western blots of SMAD2/3 (S2/3), METTL3 (M3), or control (IgG) immunoprecipitations (IPs) from nuclear extracts of hESCs (representative of three experiments). Input is 5% of the material used for IP. In b, IPs were performed from hESCs maintained in presence of Activin or treated for 1h with SB-431542 (SB; Activin/Nodal inhibitor). For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1. (c) Proximity ligation assays (PLA) for SMAD2/3 and WTAP in hESCs maintained in presence of Activin or SB (representative of two experiments). Scale bars: 10μm. DAPI: nuclei. (d) PLA quantification; the known SMAD2/3 cofactor NANOG was used as positive control10. Mean ± SEM, n=4 PLA. 2-way ANOVA with post-hoc Holm-Sidak comparisons: **=p<0.01, and ***=p<0.001. (e) Representative results of nuclear-enriched m6A methylated RNA immunoprecipitation followed by deep-sequencing (m6A NeMeRIP-seq; n=3 cultures, replicates combined for visualization). Signal represents read enrichment normalized by million mapped reads and library size. GENCODE gene annotations (red: coding exons; white: untranslated exons; all potential exons are shown and overlaid), and SMAD2/3 binding sites from ChIP-seq data30 are shown. (f-g) RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments for WTAP, SMAD2/3, or IgG control in hESCs maintained in presence of Activin or treated with SB. RPLP0 and PBGD were used as negative controls as they present no m6A. f: mean ± SEM, n=3 cultures. 2-way ANOVA with post-hoc Holm-Sidak comparisons: *=p<0.05, and **=p<0.01. g: mean, n=2 cultures. (h) Model for the mechanism by which SMAD2/3 promotes m6A deposition. P: phosphorylation; W: WTAP; M14: METTL14.

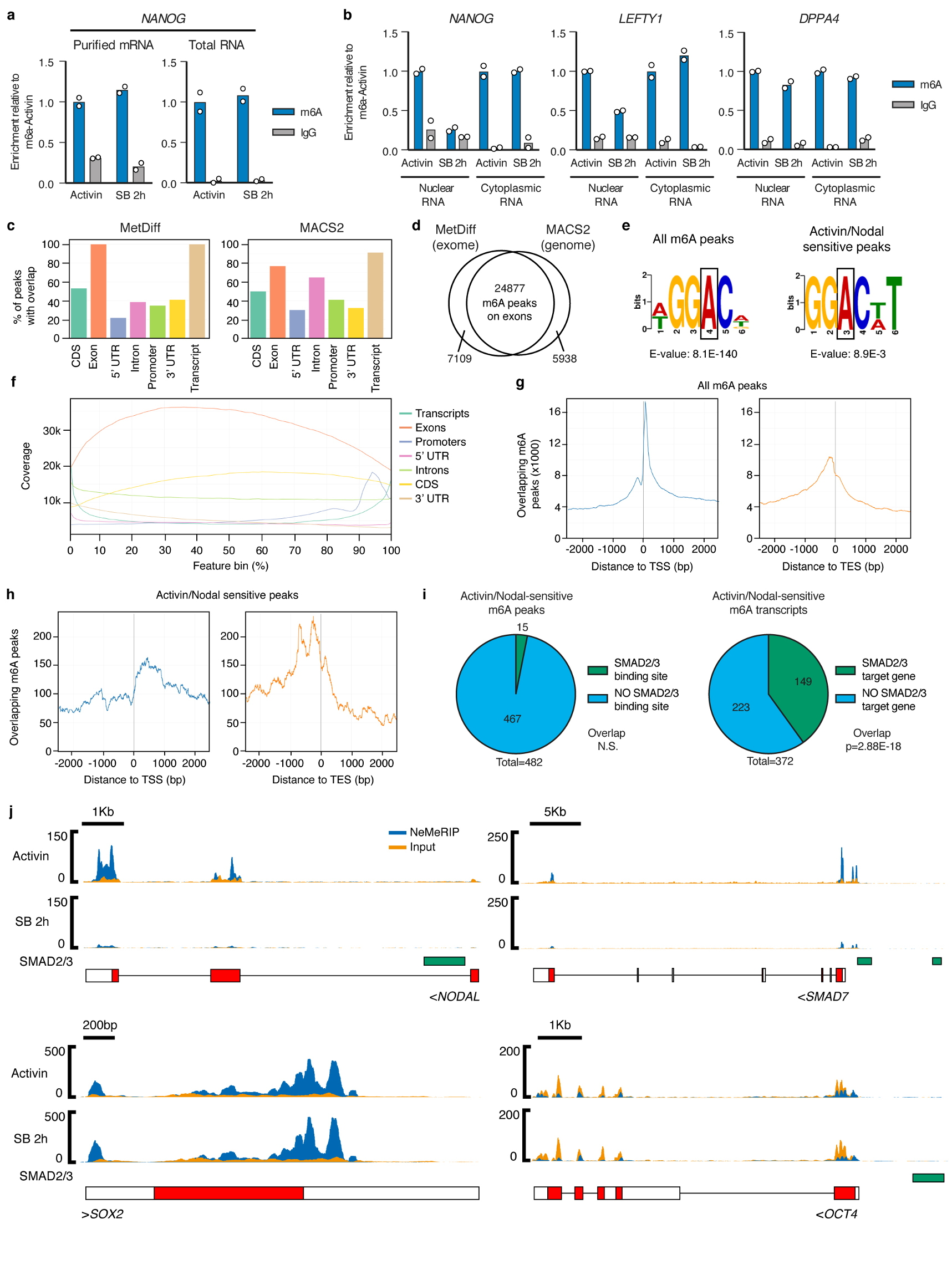

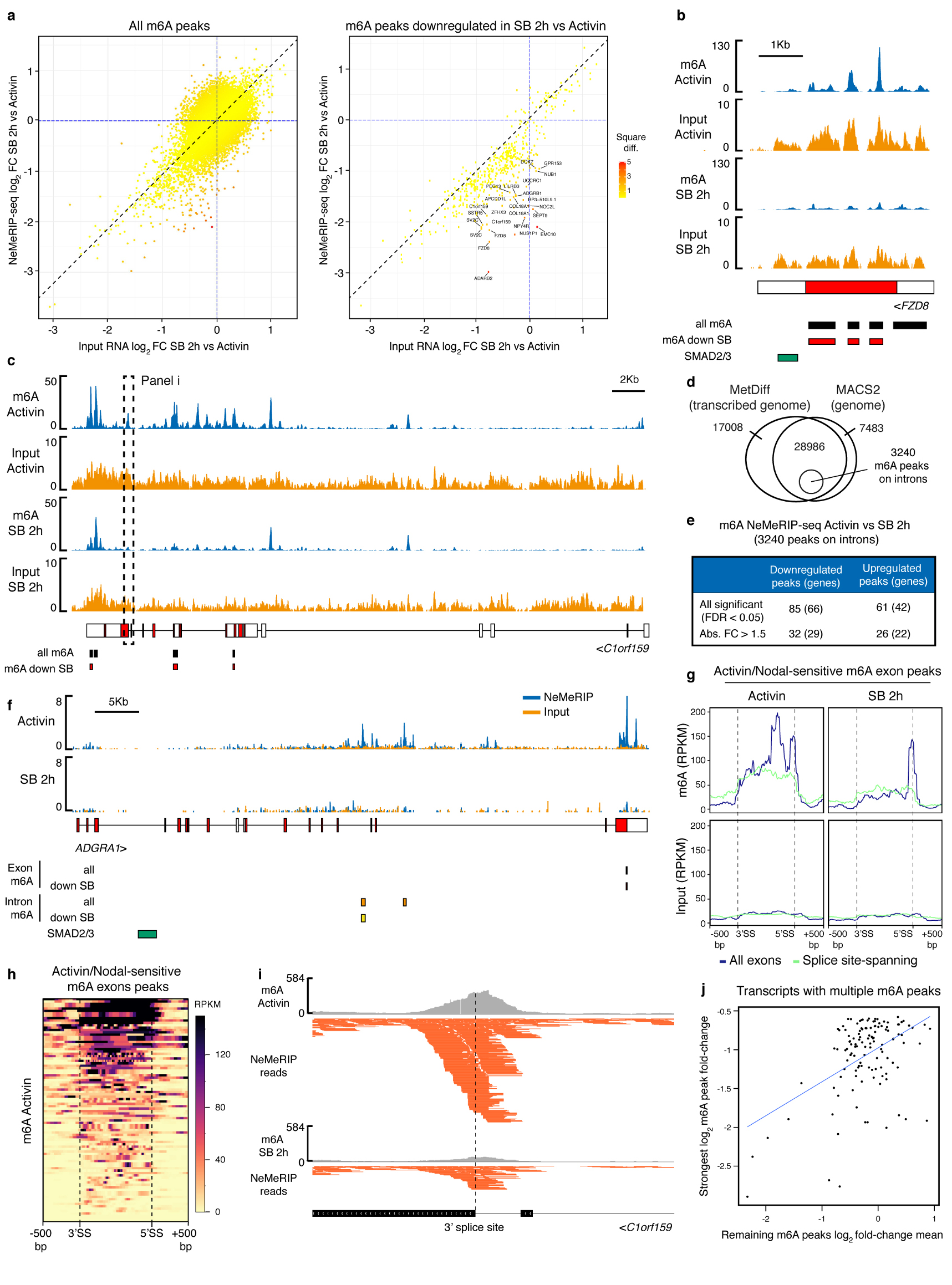

To investigate the functional relevance of this interaction, we assessed the transcriptome-wide effects of Activin/Nodal inhibition on the deposition of m6A by performing nuclear-enriched m6A methylated RNA immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (NeMeRIP-seq; Extended Data Fig. 5a-d, and Supplementary Discussion). In agreement with previous reports17,19,24, deposition of m6A onto exons was enriched around stop codons and transcription start sites, and occurred at a motif corresponding to the m6A consensus sequence (Extended Data Fig. 5e-g). Assessment of differential m6A deposition revealed that Activin/Nodal inhibition predominantly resulted in reduced m6A levels in selected transcripts (Supplementary Table 2; average absolute log2 fold-change of 0.56 and 0.35 for m6A decrease and increase, respectively). Decrease in m6A deposition was predominantly observed on peaks located near to stop codons (Extended Data Fig. 5h), a location which has been reported to decrease the stability of mRNAs16,24,25. Interestingly, transcripts showing reduced m6A levels after Activin/Nodal inhibition largely and significantly overlapped with genes bound by SMAD2/3 (Extended Data Fig. 5i), including well-known transcriptional targets such as NANOG, NODAL, LEFTY1, and SMAD7 (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 5j). Accordingly, Activin/Nodal-sensitive m6A deposition was largely associated with transcripts rapidly decreasing during the exit from pluripotency triggered by Activin/Nodal inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Transcripts behaving in this fashion were enriched in pluripotency regulators and in factors involved in the Activin/Nodal signalling pathway (Supplementary Table 3). On the other hand, the expression of a large number of developmental regulators associated to Activin/Nodal-sensitive m6A deposition remained unchanged following Activin/Nodal inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 6a-c and Supplementary Table 3). Considered together, these findings establish that Activin/Nodal signalling can regulate m6A deposition on a number of specific transcripts.

We then examined the underlying molecular mechanisms. RNA immunoprecipitation experiments on nuclear RNAs showed that inhibition of Activin/Nodal signalling impaired binding of WTAP to multiple m6A-marked transcripts including NANOG and LEFTY1 (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 4d-e), while SMAD2/3 itself interacted with such transcripts in the presence of Activin/Nodal signalling (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 4e). Thus, SMAD2/3 appears to promote the recruitment of the m6A methyltransferase complex onto nuclear RNAs. Interestingly, recent reports have established that m6A deposition occurs co-transcriptionally and involves nascent pre-RNAs16,26,20. Considering the broad overlap between SMAD2/3 transcriptional targets and transcripts showing Activin/Nodal-sensitive m6A deposition (Extended Data Fig 5i), we therefore hypothesized that SMAD2/3 could facilitate co-transcriptional recruitment of the m6A methyltransferase complex onto nascent transcripts. Supporting this notion, inhibition of Activin/Nodal signalling mainly resulted in downregulation of m6A not only on exons, but also onto pre-mRNA-specific features such as introns and exon-intron junctions (Extended Data Fig. 6d-i and Supplementary Table 2). Moreover, we observed a correlation in Activin/Nodal sensitivity for m6A peaks within the same transcript (Extended Data Fig. 6j), suggesting that SMAD2/3 regulates m6A deposition at the level of a genomic locus rather than on a specific mRNA peak. Nevertheless, a stable and direct binding of the m6A methyltransferase complex to the DNA could not be detected (Extended Data Fig. 4f). Thus, co-transcriptional recruitment might rely on indirect and dynamic interactions with the chromatin. Considering all these results, we propose a model in which Activin/Nodal signalling promotes co-transcriptional m6A deposition by facilitating the recruitment of the m6A methyltransferase complex onto nascent mRNAs (Fig. 2h).

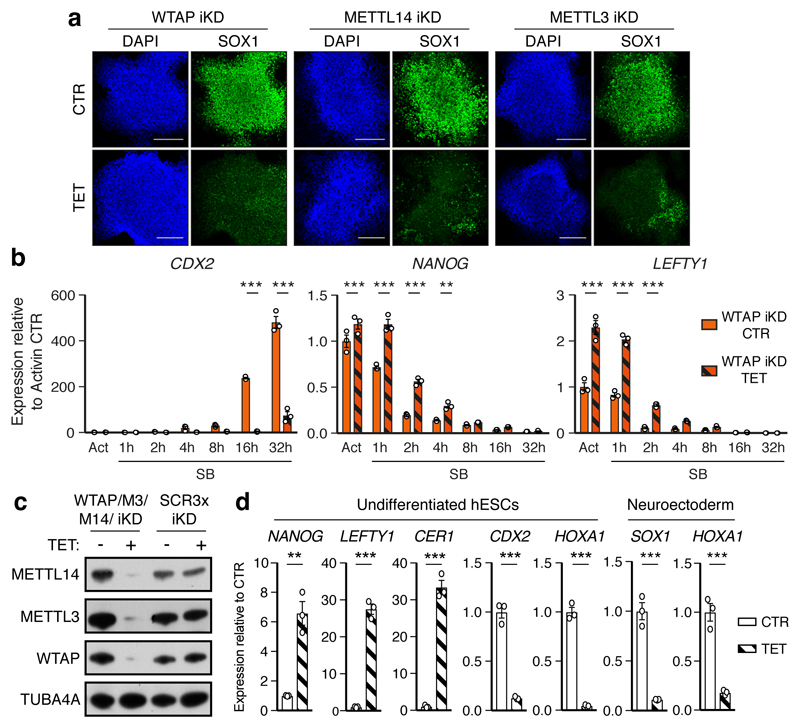

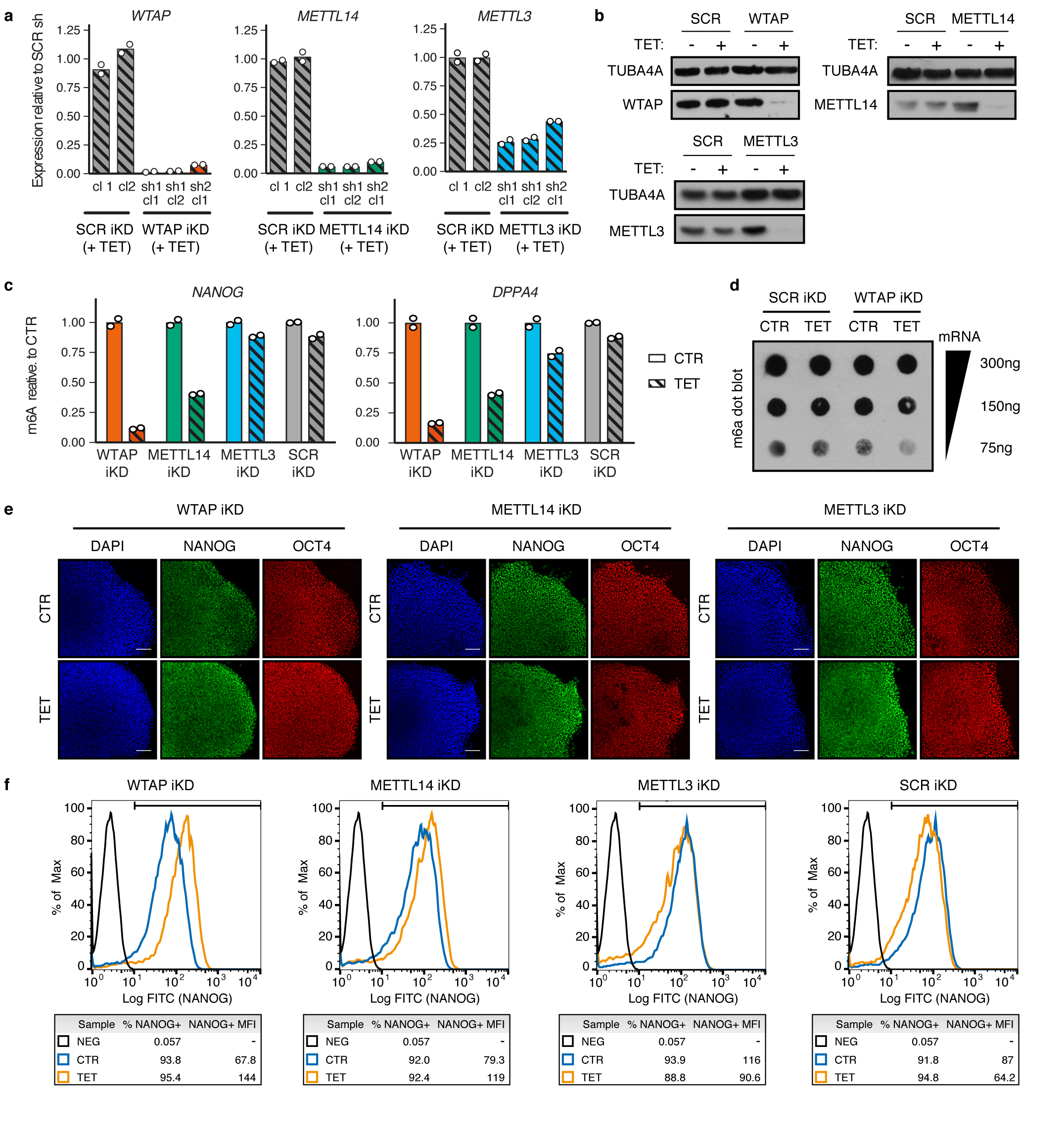

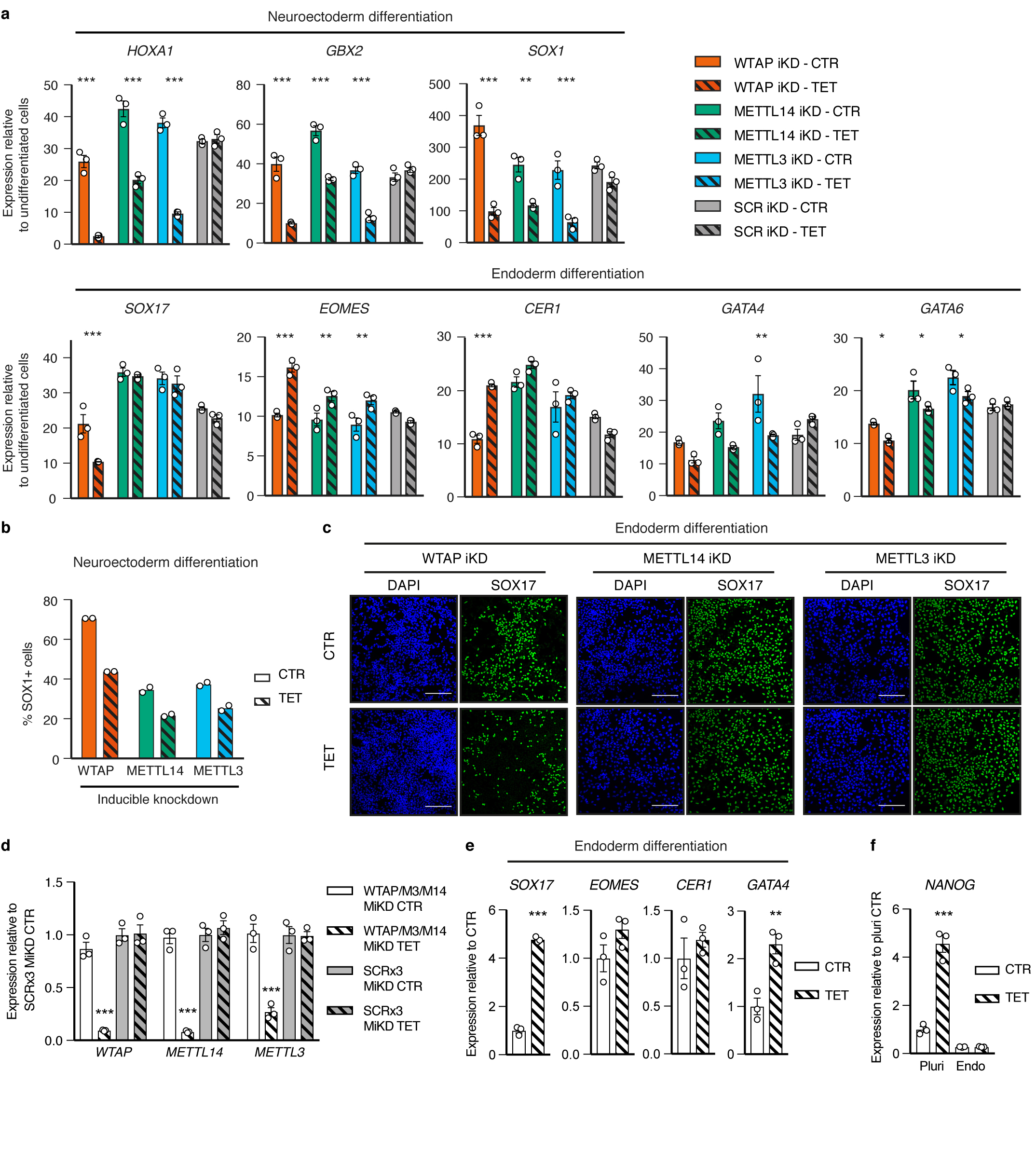

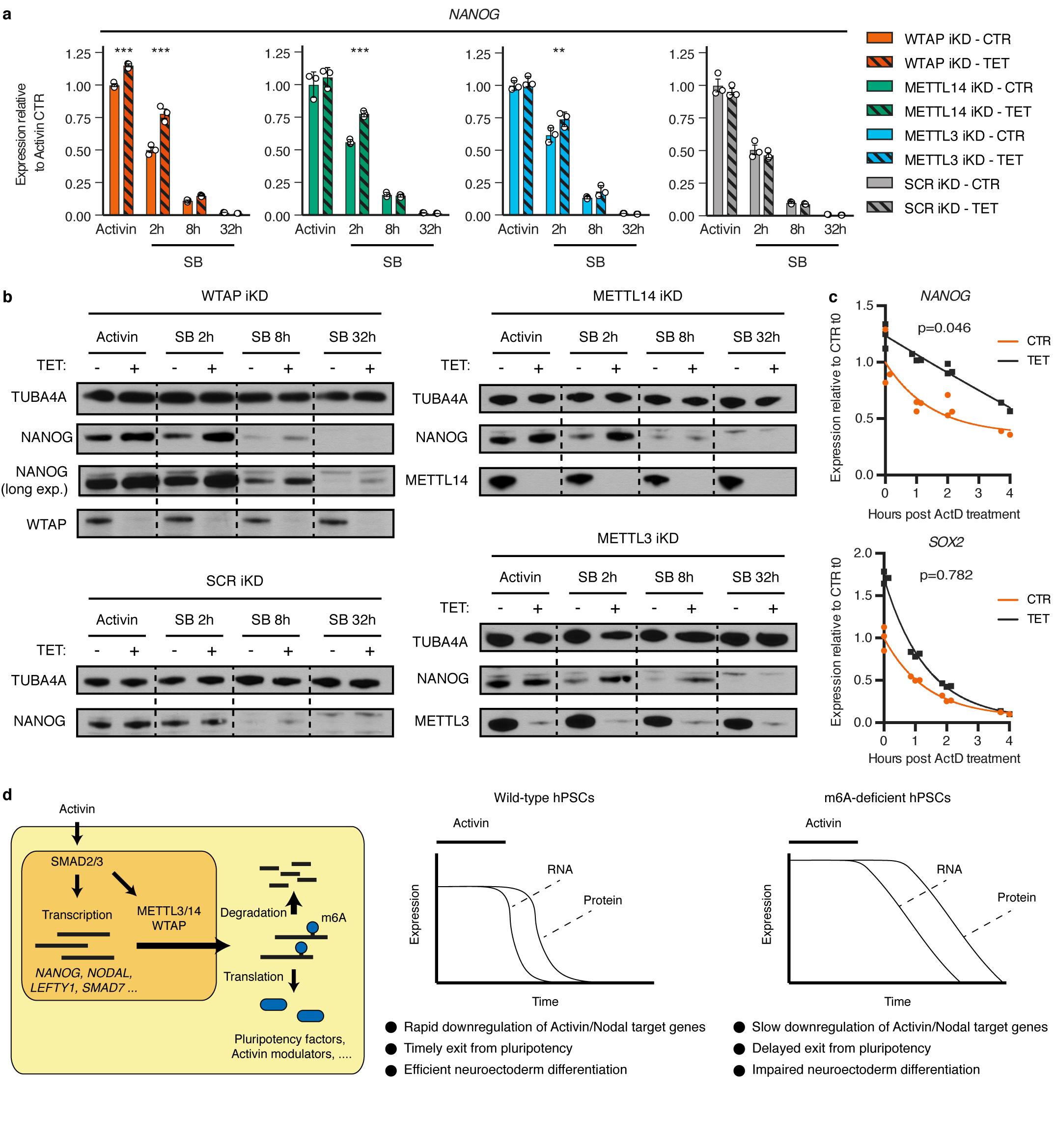

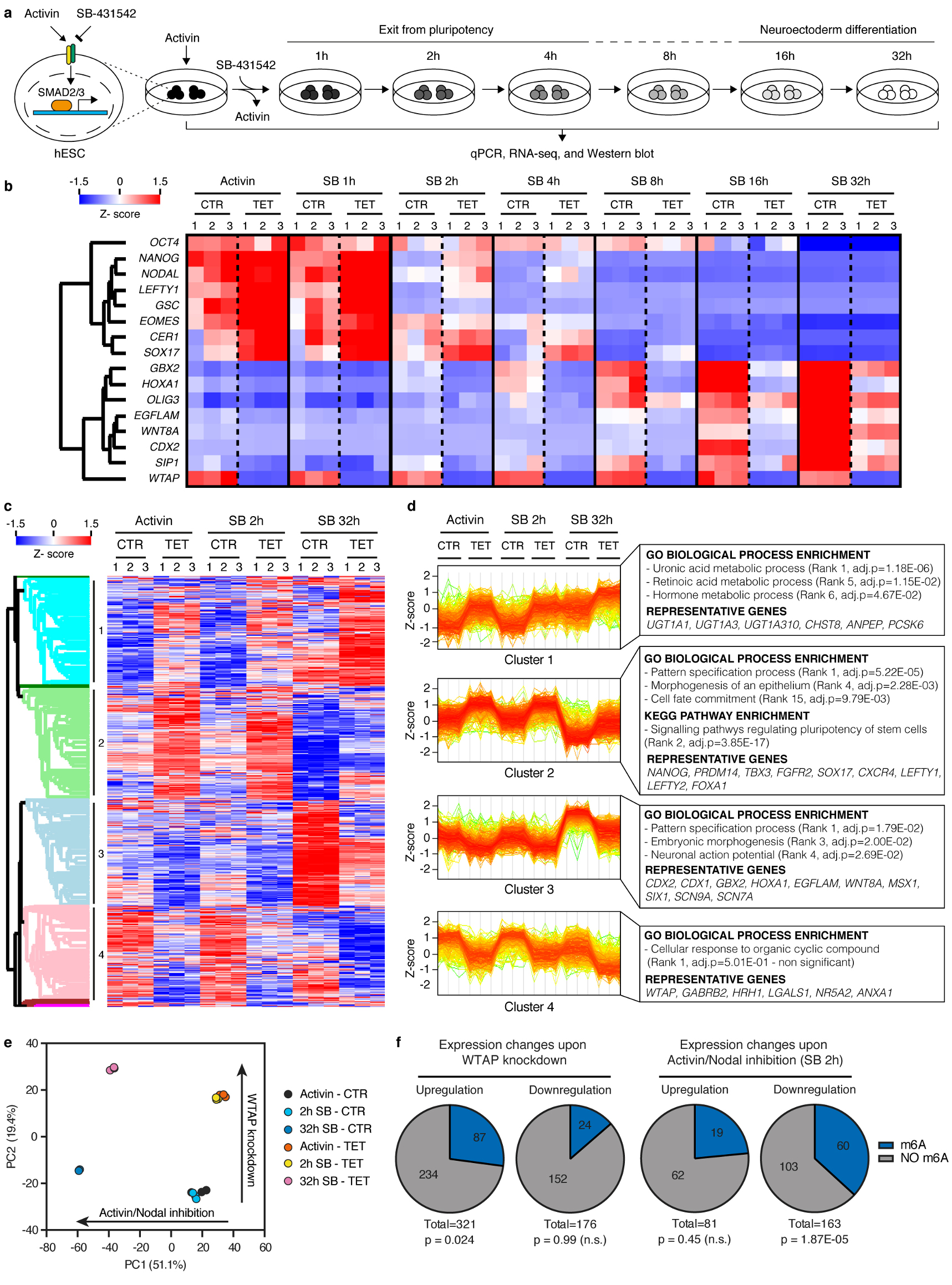

To understand the functional relevance of these regulations in the context of hPSC cell fate decisions, we performed inducible knockdown experiments for the various subunits of the m6A methyltransferase complex27 (Extended Data Fig. 7a-b). As expected, decrease in WTAP, METTL14, or METTL3 expression reduced the deposition of m6A (Extended Data Fig 7c-d). Interestingly, prolonged knockdown did not affect pluripotency (Extended Data Fig. 7e-f). However, expression of m6A methyltransferase complex subunits was necessary for neuroectoderm differentiation induced by the inhibition of Activin/Nodal signalling, while it was dispensable for Activin-driven endoderm specification (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 8a-c). Activin/Nodal is known to block neuroectoderm induction by promoting NANOG expression28, while NANOG is required for the early stages of endoderm specification13. Therefore, we monitored the levels of this factor during neuroectoderm differentiation. We observed that both transcript and protein were upregulated following impairment of m6A methyltransferase activity (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 9a-b), while mRNA stability was increased (Extended Data Fig. 9c). These results show that m6A deposition decreases the stability of the NANOG mRNA to facilitate its downregulation upon loss of Activin/Nodal signalling, thus facilitating exit from pluripotency and neuroectoderm specification (Extended Data Fig. 9d). Additional transcriptomic analyses showed that WTAP knockdown resulted in a global upregulation of genes transcriptionally activated by SMAD2/3 in hESCs, while it impaired the upregulation of genes induced by Activin/Nodal inhibition during neuroectoderm differentiation (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 10a-e, Supplementary Table 4, and Supplementary Discussion). Importantly, the decrease in WTAP expression also led to the upregulation of mRNAs marked by m6A (Extended Data Fig. 10f), confirming that WTAP-dependent m6A deposition destabilises mRNAs16,24,25. Moreover, transcripts rapidly downregulated after Activin/Nodal inhibition were enriched in m6A-marked mRNAs (Extended Data Fig. 10f). Finally, simultaneous knockdown of METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP in hESCs resulted in an even stronger dysregulation of Activin/Nodal target transcripts (Fig. 3c-d and Extended Data Fig. 8d) and defective neuroectoderm differentiation (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 8e-f). Taken together, these results indicate that the interaction of SMAD2/3 with METTL3-METTL14-WTAP can promote m6a deposition on a subset of transcripts, including a number of pluripotency regulators that are also transcriptionally activated by Activin/Nodal signalling. The resulting negative feedback destabilizes these mRNAs and causes their rapid degradation following inhibition of Activin/Nodal signalling. This mechanism allows timely exit from pluripotency and induction of neuroectoderm differentiation (Extended Data Fig. 9d).

Figure 3. The m6A methyltransferase complex antagonizes Activin/Nodal signalling in hPSCs to promote timely exit from pluripotency.

(a) Immunofluorescence for neural marker SOX1 following neuroectoderm differentiation of tetracycline (TET)-inducible knockdown (iKD) hESCs (representative of two experiments). CTR: no TET; DAPI: nuclei. Scale bars: 100μm. (b) qPCR analyses in WTAP iKD hESCs subjected to Activin/Nodal signalling inhibition with SB for the indicated time. Act: Activin. Mean ± SEM, n=3 cultures. 2-way ANOVA with post-hoc Holm-Sidak comparisons: **=p<0.01, and ***=p<0.001. (c) Western blot validation of multiple inducible knockdown (MiKD) hESCs for WTAP, METTL3 (M3), and METTL14 (M14). Cells expressing three copies of the scrambled shRNA (SCR3x) were used as negative control. (d) qPCR analyses in undifferentiated MiKD hESCs, or following their neuroectoderm differentiation. Mean ± SEM, n=3 cultures. Two-tailed t-test: **=p<0.01, and ***=p<0.001.

To conclude, this first analysis of the SMAD2/3 interactome reveals novel interplays between TGFβ signalling and a diversity of cellular processes. Our results suggest that SMAD2/3 could act as a hub coordinating several proteins known to have a role in mRNA processing and modification, apoptosis, DNA repair, and transcriptional regulation. This possibility is illustrated by our results regarding Activin/Nodal-sensitive regulation of m6A. Indeed, through the interaction between SMAD2/3 and the METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex, Activin/Nodal signalling connects transcriptional and epitranscriptional regulations to “poise” several of its transcriptional targets for rapid degradation upon signalling withdrawal (Extended Data Fig. 9d). As a result, this avoids overlaps between the pluripotency and neuroectoderm transcriptional programs, thereby facilitating changes in cell identity. We anticipate that further studies will clarify the other “non canonical” functions of SMAD2/3, and will dissect how these are interrelated with chromatin epigenetic, transcriptional, and epitranscriptional regulations.

Our findings also clarify and substantially broaden our understanding of the function of m6A in cell fate decisions. They establish that depletion of m6A in hPSCs does not lead to differentiation, contrary to predictions from studies in mouse epiblast stem cells22. This could imply important functional differences in epitranscriptional regulations between the human and murine pluripotent state. Moreover, widening the conclusions from previous reports23, we demonstrate that deposition of m6A is specifically necessary for neuroectoderm induction, but not for definitive endoderm differentiation. This can be explained by the fact that in contrast to its strong inhibitory effect on the neuroectoderm lineage28, expression of NANOG is actually necessary for the early stages of mesendoderm specification13,29. Finally, our results establish that m6A is a dynamic event directly modulated by extracellular clues such as TGFβ. Considering the broad importance of TGFβ signalling, the regulation we describe here might have an essential function in many cellular contexts requiring a rapid response or change in cell state, such as the inflammatory response or cellular proliferation.

Methods

hPSC culture and differentiation

Feeder- and serum-free culture of hESCs (H9/WA09 line; WiCell) and hiPSCs (A1ATR/R;31) was previously described32. Briefly, cells were plated on gelatin- and MEF medium-coated plates, and cultured in chemically defined medium (CDM) containing bovine serum albumin (BSA). CDM was supplemented with 10ng/ml Activin-A and 12ng/ml FGF2 (both from Dr Marko Hyvonen, Dept. of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge). Cells were passaged every 5-6 days with Collagenase IV, and plated as clumps of 50-100 cells dispensed at a density of 100-150 clumps/cm2. Differentiation was initiated in adherent hESC cultures 48h following passaging. Definitive endoderm specification was induced for 3 days (unless stated otherwise) by culturing cells in CDM (without insulin) with 20ng/ml FGF2, 10μM LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor; Promega), 100ng/ml Activin-A, and 10ng/ml BMP4 (R&D), as previously described33. Neuroectoderm was induced for 3 days (unless stated otherwise) in CDM-BSA with 12ng/ml FGF2 and 10μM SB-431542 (Activin/Nodal/TGFβ signalling inhibitor; Tocris), as previously described34. These same culture conditions were used for Activin/Nodal signalling inhibition experiments. hPSCs were routinely monitored for absence of karyotypic abnormalities and mycoplasma infection. Since hESCs were obtained by a commercial supplier cell line identification was not performed. hiPSCs were previously generated in house and genotyped by Sanger sequencing31.

Molecular cloning

Plasmids carrying inducible shRNAs were generated by cloning annealed oligonucleotides into the pAAV-Puro_iKD or pAAV-Puro_siKD vectors as previously described27. All shRNA sequences were obtained from the RNAi Consortium TRC library35 (https://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/public/). Whenever shRNAs had been validated, the most powerful ones were chosen (the sequences are reported in Supplementary Table 5). Generation of a vector containing shRNAs against METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP (cloned in in this order) was performed by Gibson assembly of PCR products containing individual shRNA cassettes, as previously described27. The resulting was named pAAV-Puro_MsiKD-M3M14W. Generation of the matched control vector containing three copies of the scrambled shRNA sequence (pAAV-Puro_MsiKD-SCR3x) was previously described27.

A targeting vector for the AAVS1 locus carrying constitutively-expressed NANOG was generated starting from pAAV_TRE-EGFP36. First, the TRE-EGFP cassette was removed using PspXI and EcoRI, and substituted with the CAG promoter (cut from pR26-CAG_EGFP27 using SpeI and BamHI) by ligating blunt-ended fragments. The resulting vector (pAAV-Puro_CAG) was then used to clone full-length the NANOG transcript, which includes its full 5’ and 3’ UTR. The full-length NANOG transcript was constructed from 3 DNA fragments. The 5’ (1–301bp) and 3’ (1878–2105bp) ends were synthesised (IDT) with 40bp overlaps corresponding to pGem3Z vector linearised with SmaI. The middle fragment was amplified from cDNA of H9 hESCs obtained by retrotranscription with poly-T primer using primers 5’-TTGTCCCCAAAGCTTGCCTTGCTTT-3’and 5’–CAAAAACGGTAAGAAA-TCAATTAA-3’. The three fragments and the linearized vector were assembled using a Gibson reaction (NEB) and the sequence of the construct was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The full length NANOG transcript was then subcloned into KpnI- and EcoRV-digested pAAV-Puro_CAG following KpnI and HincII digestion. The resulting vector was named pAAV-Puro_CAG-NANOG.

Inducible gene knockdown

Clonal inducible knockdown hESCs for METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, or matched controls expressing a scrambled (SCR) shRNA were generated by gene targeting of the AAVS1 locus with pAAV-Puro_siKD plasmids, which was verified by genomic PCR, all as previously described27,36. This same approach was followed to generate multiple inducible knockdown hESCs for METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP (plasmid pAAV-Puro_MsiKD-M3M14W), or matched controls expressing three copies of the SCR shRNA (plasmid pAAV-Puro_MsiKD-SCR3x). Inducible knockdown hESCs for SMAD2, FOXH1, SETDB1, EP300, CREBBP, B2M, and matched controls expressing a scrambled shRNA were generated using pAAV-Puro_iKD vectors27 in hESCs expressing a randomly integrated wild-type tetR. Two wells were transfected for each shRNA in order to generate independent biological replicates. Following selection with puromycin, all the resulting targeted cells in each well were pooled and expanded for further analysis. Given that 20 to 50 clones were obtained for each well, we refer to these lines as “clonal pools”. Gene knockdown was induced by adding tetracycline hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) to the culture medium at the concentration of 1μg/ml. Unless indicated owtherwise in the text or figure legends, inducible knockdown in undifferentiated hESCs was induced for 5 days, while differentiation assays were performed in hESCs in which knockdown had been induced for 10 days.

Generation of NANOG overexpressing hESCs

NANOG overexpressing H9 hESCs were obtained by zinc finger nuclease (ZFN)-facilitated gene targeting of the AAVS1 locus with pAAV-Puro_CAG-NANOG. This was performed by lipofection of the targeting vector and zinc-finger plasmids followed by puromycin selection, clonal isolation, and genotyping screening of targeted cells, all as previously described27.

SMAD2/3 co-immunoprecipitation

Approximately 2x107 cells were used for each immunoprecipitation (IP). Unless stated otherwise, all biochemical steps were performed on ice or at 4°C, and ice-cold buffers were supplemented with cOmplete Protease Inhibitors (Roche), PhosSTOP Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche), 1mg/ml Leupeptin, 0.2mM DTT, 0.2mM PMSF, and 10mM sodium butyrate (all from Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were fed with fresh medium for 2h before being washed with PBS, scraped in cell dissociation buffer (CDB, Gibco), and pelleted at 250g for 10’. The cell pellet was then washed once with 10 volumes of PBS, and once with 10 volumes of hypotonic lysis buffer (HLB: 10mM HEPES pH 7.6; 10mM KCl; 2mM MgCl2; 0.2mM EDTA; 0.2mM EGTA). The pellet was resuspended in 5 volumes of HLB and incubated for 5’ to induce cell swelling. The resulting cell suspension was homogenized using the “loose” pestle of a Dounce homogenizer (Jencons Scientific) for 35-50 strokes until plasma membrane lysis was complete (as judged by microscopic inspection). The nuclei were pelleted at 800g for 5’, washed once with 10 volumes of HLB, and resuspended in 1.5 volumes of high-salt nuclear lysis buffer (HSNLB: 20mM HEPES pH 7.6; 420mM NaCl; 2mM MgCl2; 25% glycerol; 0.2mM EDTA; 0.2mM EGTA). High-salt nuclear extraction was performed by homogenizing the nuclei using the “tight” pestle of a Dounce homogenizer for 70 strokes, followed by 45’ of incubation in rotation. The resulting lysate was clarified for 30’ at 16,000g, and transferred to a dialysis cassette using a 19-gauge syringe. Dialysis was performed for 4h in 1l of dialysis buffer (DB: 20mM HEPES pH 7.6; 50mM KCl; 100mM NaCl; 2mM MgCl2; 10% glycerol; 0.2mM EDTA; 0.2mM EGTA) under gentle stirring, and the buffer was changed once after 2h. After the dialysis, the sample was clarified from minor protein precipitates for 10’ at 17,000g, and the protein concentration was assessed. Immunoprecipitations were performed by incubating 0.5mg of protein with 5μg of goat polyclonal SMAD2/3 antibody (R&D systems, catalogue number: AF3797) or goat IgG negative control antibody (R&D systems, catalogue number: AB-108-C) for 3h at 4°C in rotation. This was followed by incubation with 10μl of Protein G-Agarose for 1h. Beads were finally washed three times with DB, and finally processed for Western blot or mass spectrometry. This co-immunoprecipitation protocol is referred to as “co-IP2” in the Supplementary Discussion and in Extended Data Fig. 1. The alternative SMAD2/3 co-immunoprecipitation protocol (co-IP1) was previously described10.

Mass spectrometry

Label-free quantitative mass spectrometric analysis of proteins co-immunoprecipitated with SMAD2/3 or from control IgG co-immunoprecipitations was performed on three replicates for each condition. After immunoprecipitation, samples were prepared as previously described37 with minor modifications. Proteins were eluted by incubation with 50μl of 2M urea and 10mM DTT for 30’ at RT in agitation. Then, 55mM chloroacetamide was added for 20’ to alkylate reduced disulphide bonds. Proteins were pre-digested on the beads with 0.4μg of mass spectrometry-quality trypsin (Promega) for 1h at RT in agitation. The suspension was cleared from the beads by centrifugation. The beads were then washed with 50ul of 2M Urea, and the merged supernatants were incubated overnight at RT in agitation to complete digestion. 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid was then added to inactivate trypsin, and peptides were loaded on C18 StageTips38. Tips were prepared for binding by sequential equilibration for 2’ at 800g with 50μl methanol, 50μl Solvent B (0.5% acetic acid; 80% acetonitrile), and 50μl Solvent A (0.5% acetic acid). Subsequently, peptides were loaded and washed twice with Solvent A. Tips were dry-stored until analysis. Peptides were eluted from the StageTips and separated by reversed-phase liquid chromatography on a 2.5h long segmented gradient using EASY-nLC 1000 (ThermoFisher Scientific). Eluting peptides were ionized and injected directly into a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The mass spectrometer was operated in a TOP10 sequencing mode, meaning that one full mass spectrometry (MS) scan was followed by higher energy collision induced dissociation (HCD) and subsequent detection of the fragmentation spectra of the 10 most abundant peptide ions (tandem mass spectrometry; MS/MS). Collectively, ~160000 isotype patterns were generated resulting from ~6000 mass spectrometry (MS) runs. Consequently, ~33000 tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectra were measured.

Quantitative mass spectrometry based on dimethyl labelling of samples was performed as described for label-free quantitative mass spectrometry but with the following differences. Dimethyl labelling was performed as previously reported39,40. Briefly, trypsin digested protein samples were incubated with dimethyl labelling reagents (4μl of 0.6M NaBH3CN together with 4μl of 4% CH2O or CD2O for light or heavy labelling, respectively) for 1h at RT in agitation. The reaction was stopped by adding 16μl of 1% NH3. Samples were acidified with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, and finally loaded on stage-tips. Each immunoprecipitation was performed twice, switching the labels.

Analysis of mass spectrometry data

The raw label-free quantitative mass spectrometric data was analysed using the MaxQuant software suite41. Peptide spectra were searched against the human database (Uniprot) using the integrated Andromeda search engine, and peptides were identified with an FDR<0.01 determined by false matches against a reverse decoy database. Peptides were assembled into protein groups with an FDR<0.01. Protein quantification was performed using the MaxQuant label-free quantification algorithm requiring at least 2 ratio counts, in order to obtain label free quantification (LFQ) intensities. Collectively, the MS/MS spectra were matched to ~20000 known peptides, leading to the identification of 3635 proteins in at least one of the conditions analysed. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the Perseus software package (MaxQuant). First, common contaminants and reverse hits were removed, and only proteins identified by at least two peptides (one of those being unique to the respective protein group) were considered as high-confidence identifications. Proteins were then filtered for having been identified in all replicates of at least one condition. LFQ intensities were logarithmized, and missing intensity values were imputed by representing noise values42. One-tailed t-tests were then performed to determine the specific interactors in each condition by comparing the immunoprecipitations with the SMAD2/3 antibody against the IgG negative controls. Statistical significance was set with a permutation-based FDR<0.05 (250 permutations). Fold-enrichment over IgG controls were calculated from LFQ intensities.

This same pipeline was used to analyze mass spectrometry data based on dimethyl labelling, with the following two exceptions. First, an additional mass of 28.03Da (light) or 32.06Da (heavy) was specified as “labels” at the N-terminus and at lysines. Second, during statistical analysis of mass spectrometry data the outlier significance was calculated based on protein intensity (Significance B41), and was required to be below 0.05 for both the forward and the reverse experiment.

Biological interpretation of mass spectrometry data

The SMAD2/3 protein-protein interaction network was generated using Cytoscape v2.8.343. First, all the annotated interactions involving the SMAD2/3 binding proteins were inferred by interrogating protein-protein interaction databases through the PSIQUIC Universal Web Service Client. IMEx-complying interactions were retained and merged by union. Then, a subnetwork involving only the SMAD2/3 interactors was isolated. Finally, duplicate nodes and self-loops were removed to simplify visualization. Note that based on our results all the proteins shown would be connected to SMAD2/3, but such links were omitted to simplify visualization and highlight those interactions with SMAD2/3 that were already known. Proteins lacking any link and small complexes of less than three factors were not shown to improve presentation clarity. Note that since the nodes representing SMAD2 and SMAD3 shared the very same links, they were fused into a single node (SMAD2/3). Functional enrichment analysis was performed using the Fisher’s exact test implemented in Enrichr44, and only enriched terms with a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value<0.05 were considered. For Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, the 2015 GO annotation was used. For mouse phenotype enrichment analysis, the level 3 of the Mouse Genomic Informatics (MGI) annotation was used. To compare protein abundance in different conditions, a cut-off of absolute LFQ intensity log2 fold-change larger than 2 was chosen, as label-free mass spectrometry is at present not sensitive enough to detect smaller changes with confidence37.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

PLA was performed using the Duolink In Situ Red Starter Kit Goat/Rabbit (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were cultured on glass coverslips and prepared by fixation in PBS 4% PFA for 10’ at RT, followed by two gentle washes in PBS. All subsequent incubations were performed at RT unless otherwise stated. Samples were permeablilized in PBS 0.25% Triton X-100 for 20’, blocked in PBS 0.5% BSA for 30’, and incubated with the two primary antibodies of interest (diluted in PBS 0.5% BSA; see Supplementary Table 6) for 1h at 37°C in a humid chamber. The Duolink In Situ PLA probes (anti-rabbit minus and anti-goat plus) were mixed and diluted 1:5 in PBS 0.5% BSA, and pre-incubated for 20’. Following two washes with PBS 0.5% BSA, the coverslips were incubated with the PLA probe solution for 1h at 37°C in a humid chamber. Single-antibody and probes-only negative controls were performed for each antibody tested to confirm assay specificity. Coverslips were washed twice in Wash Buffer A for 5’ under gentle agitation, and incubated with 1x ligation solution supplemented with DNA ligase (1:40 dilution) for 30’ at 37°C in a humid chamber. After two more washes in Wash Buffer A for 2’ under gentle agitation, coverslips were incubated with 1x amplification solution supplemented with DNA polymerase (1:80 dilution) for 1h 40’ at 37°C in a humid chamber. Samples were protected from light from this step onwards. Following two washes in Wash Buffer B for 10’, the coverslips were dried overnight, and finally mounted on a microscope slide using Duolink In Situ Mounting Medium with DAPI. Images of random fields of view were acquired using a LSM 700 confocal microscope (Leica) using a Plan-Apochromat 40x/1.3 Oil DIC M27 objective, performing z-stack with optimal spacing (~0.36μm). Images were automatically analysed using ImageJ. For this, nuclear (DAPI) and PLA z-stacks were first individually flattened (max intensity projection) and thresholded to remove background noise. Nuclear images were further segmented using the watershed function. Total nuclei and PLA spots were quantified using the analyse particle function of ImageJ, and nuclear PLA spots were quantified using the speckle inspector function of the ImageJ plugin BioVoxxel.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

Approximately 2x107 cells were used for each RIP. Unless stated otherwise, all biochemical steps were performed on ice or at 4°C, and ice-cold buffers were supplemented with cOmplete Protease Inhibitors (Roche) and PhosSTOP Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche). Cells were fed with fresh culture medium 2h before being washed once with RT PBS and UV cross-linked in PBS at RT using a Stratalinker 1800 at 254nm wavelength (irradiation of 400mJ/cm2). Crosslinked cells were scraped in cell dissociation buffer (CDB, Gibco) and pelleted at 250g for 5’. The cell pellet was incubated in five volumes of isotonic lysis buffer (ILB: 10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 3mM CaCl2; 2mM MgCl2; 0.32M sucrose) for 12’ to induce cell swelling. Then, Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 0.3%, and cells were incubated for 6’ to lyse the plasma membranes. Nuclei were pelleted at 600g for 5’, washed once with ten volumes of ILB, and finally resuspended in two volumes of nuclear lysis buffer (NLB: 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 100mM NaCl; 50mM KCl; 3mM MgCl2; 1mM EDTA; 10% glycerol; 0.1% Tween) supplemented with 800U/ml RNasin Ribonuclease Plus Inhibitor (Promega) and 1μM DTT. The nuclear suspension was transferred to a Dounce homogenizer (Jencons Scientific) and homogenized by performing 70 strokes with a “tight” pestle. The nuclear lysate was incubated in rotation for 30’, homogenized again by perfoming 30 additional strokes with the tight pestle, and incubated in rotation for 15’ more minutes at RT after addition of 12.5μg/ml of DNase I (Sigma). The protein concentration was assessed, and approximately 1mg of protein was used for overnight IP in rotation with the primary antibody of interest (Supplementary Table 6), or with equal amounts of non-immune species-matched IgG. 10% of the protein lysate used for IP was saved as pre-IP input and stored at -80°C for subsequent RNA extraction. IPs were incubated for 1h with 30μl of Protein G-Agarose, then washed twice with 1ml of LiCl wash buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 250mM LiCl; 0.1% Triton X-100; 1mM DTT) and twice with 1ml of NLB. Beads were resuspended in 90μl of 30mM Tris-HCl pH 9.0, and DNase-digested using the RNase-free DNase kit (QIAGEN) by adding 10μl of RDD buffer and 2.5μl of DNase. The pre-IP input samples were similarly treated in parallel, and samples were incubated for 10’ at RT. The reaction was stopped by adding 2mM EDTA and by heating at 70°C for 5’. Proteins were digested by adding 2μl of Proteinase K (20mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and by incubating at 37°C for 30’. Finally, RNA was extracted by using 1ml of TriReagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the supplier’s instructions. The RNA was resuspended in nuclease-free water, and half of the sample was subjected to retrotranscription using SuperScript II (ThermoFisher) using the manufacturer’s protocol. The other half was subjected to a control reaction with no reverse transcriptase to confirm successful removal of DNA contaminants. Samples were quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), and normalized first to the pre-IP input and then to the IgG control using the ΔΔCt approach (see below). Supplementary Table 5 reports all the primers used.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Approximately 2x107 cells were used for each ChIP, and cells were fed with fresh media 2h before collection. ChIP was performed using a previously described protocol10,30. Briefly, cells were cross-linked on plates first with protein-protein crosslinkers (10mM dimethyl 3,3’-dithiopropionimidate dihydrochloride and 2.5mM 3,3’-dithiodipropionic acid di-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester; Sigma-Aldrich) for 15’ at RT, then with 1% formaldehyde for 15’. Cross-linking was quenched with glycine, after which cells were collected, subjected to nuclear extraction, and sonicated to fragment the DNA. Following pre-clearing, the lysate was incubated overnight with the antibodies of interest (Supplementary Table 6) or non-immune IgG. ChIP was completed by incubation with Protein G-agarose beads followed by subsequent washes with high salt and LiCl-containing buffers (all exactly as previously described10,30). Cross-linking was reverted first by adding DTT (for disulphide bridge-containing protein-protein cross-linkers), then by incubating in high salt at high temperatures. DNA was finally purified by sequential phenol-chloroform and chloroform extractions. Samples were analysed by qPCR using the ΔΔCt approach (see Supplementary Table 5 for primer sequences). First, a region in the last exon of SMAD7 was used as internal control to normalize for background binding. Secondly, the enrichment was normalized to the one observed in non-immune IgG ChIP controls.

m6A dot blot

m6A dot blot was performed with minor modifications to what previously described23. poly-A RNA was purified from total cellular RNA using the Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (ThermoFisher), diluted in 50μl of RNA loading buffer [RLB: 2.2M formaldehyde; 50% formamide; 0.5x MOPS buffer (20mM MOPS; 12.5mM CH3COONa; 1.25mM EDTA; pH 7.0)], incubated at 55°C for 15’, and snap cooled on ice. An Amersham Hybond-XL membrane was rehydrated in water for 3’, then in 10x saline-sodium citrate buffer (SSC: 1.5M NaCl 150mM Na3C6H5O7; pH 7.0) for 10’, and finally “sandwiched” in a 96-well dot blot hybridization manifold (ThermoFisher Scientific). Following two washes of the wells with 150μl of 10x SSC, the RNA was spotted on the membrane. After ultraviolet light (UV) cross-linking for 2’ at 254nm using a Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene), the membrane was washed once with TBST buffer, and blocked for 1h at RT with Tris-buffered saline Tween buffer (TBST: 20mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 150mM NaCl; 0.1% Tween-20) supplemented with 4% non-fat dry milk. Incubations with the anti-m6A primary antibody (Synaptic System, catalogue number: 202-111; used at 1μg/ml) and the mouse-HRP secondary antibody (Supplementary Table 6) were each performed in TBST 4% milk for 1h at RT, and were followed by three 10’ washes at RT in TBST. Finally, the membrane was incubated with Pierce ECL2 Western Blotting Substrate, and exposed to X-Ray Super RX Films.

m6A nuclear-enriched methylated RNA immunoprecipitation

m6A MeRIP on nuclear-enriched RNA to be analysed by deep sequencing (NeMeRIP-seq) was performed following modifications of previously described methods23,45. 7.5x107 hESCs were used for each sample, and three biological replicates per condition were generated. Cells were fed with fresh medium for 2h before being washed with PBS, scraped in cell dissociation buffer (CDB, Gibco), and pelleted at 250g for 5’. The cell pellet was incubated in five volumes of isotonic lysis buffer (ILB: 10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 3mM CaCl2; 2mM MgCl2; 0.32M sucrose; 1,000U/ml RNAsin ribonuclease inhibitor, Promega; and 1mM DTT) for 10’ to induce cell swelling. Then, Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 0.3% and cells were incubated for 6’ to lyse the plasma membranes. Nuclei were pelleted at 600g for 5’, washed once with ten volumes of ILB. RNA was extracted from the nuclear pellet using the RNeasy midi kit (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Residual contaminating DNA was digested in solution using the RNAse-free DNase Set from QIAGEN, and RNA was re-purified by sequential acid phenol-chloroform and chloroform extractions followed by ethanol precipitation. At this stage, complete removal of DNA contamination was confirmed by qPCR of the resulting RNA without a retrotranscription step. RNA was then chemically fragmented in 20μl reactions each containing 20μg of RNA in fragmentation buffer (FB: 10mM ZnCl2; 10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0). Such reactions were incubated at 95°C for 5’, followed by inactivation with 50mM EDTA and storage on ice. The fragmented RNA was then cleaned up by ethanol precipitation. In preparation to the MeRIP, 15μg of anti m6A-antibody (Synaptic Systems, catalogue number: 202-003) or equivalent amounts of rabbit non-immune IgG were cross-linked to 0.5mg of magnetic beads by using the Dynabeads Antibody Coupling Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Following equilibration of the magnetic beads by washing with 500μl of binding buffer (BB: 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 150mM NaCl2; 1% NP-40; 1mM EDTA), MeRIP reactions were assembled with 300μg of the fragmented RNA in 3ml of BB supplemented with 3000U of RNAsin ribonuclease inhibitor. Samples were incubated at 7rpm for 1h at RT. 5μg of fragmented RNA (10% of the amount used for MeRIP) were set aside as pre-MeRIP input control. MeRIP reactions were washed twice with BB, once with low–salt buffer [LSB: 0.25x SSPE (saline-sodium phosphate-EDTA buffer: 150mM NaCl; 10mM NaHPO4-H2O; 10mM Na2-EDTA; pH 7.4); 37.5mM NaCl2; 1mM EDTA; 0.05% Tween-20), once with high-salt buffer (HSB: 0.25x SSPE; 137.5mM NaCl2; 1mM EDTA; 0.05% Tween-20), and twice with TE-Tween buffer (TTB: 10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4; 1mM EDTA; 0.05% Tween-20). Each wash was performed by incubating the beads with 500μl of buffer at 7rpm for 3’ at RT. Finally, RNA was eluted from the beads by four successive incubations with 75μl of elution buffer (EB: 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 150mM NaCl2; 20mM DTT; 0.1% SDS; 1mM EDTA) at 42°C. Both the RNA from pooled MeRIP eluates and the pre-MeRIP input were purified and concentrated by sequential acid phenol-chloroform and chloroform extractions followed by ethanol precipitation. 30μg of glycogen were added as carrier during ethanol precipitation. RNA was resuspended in 15μl of ultrapure RNAse-free water. Preparation of DNA libraries for deep sequencing was performed using the TruSeq Stranded total RNA kit (Illumina) according to manufacturer’s instructions with the following exceptions: (1) Ribo-Zero treatment was performed only for pre-NeMeRIP samples, as ribosomal RNA contamination in m6A NeMeRIP samples was minimal; (1) since samples were pre-fragmented, the fragmentation step was bypassed and 30ng of RNA for each sample were used directly for library prep; (3) due to the small size of the library, a 2-fold excess of Ampure XP beads was used during all purification steps in order to retain small fragments; (4) due to the presence of contaminating adapter dimers, the library was gel extracted using gel safe stain and a dark reader in order to remove fragments smaller than ~120bp. Pooled libraries were diluted and denatured for sequencing on the NextSeq 500 (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were pooled so as to obtain >30M unique clusters per sample. The PhiX control library (Illumina) was spiked into the main library pool at 1% vol/vol for quality control purposes. Sequencing was performed using a high output flow cell with 2x75 cycles of sequencing, which provided ~800M paired end reads from ~400M unique clusters from each lane. Overall, an average of ~33M and ~54M paired-end reads were generated for m6A MeRIP and pre-MeRIP samples, respectively.

Samples for m6A MeRIP to be analysed by qPCR (NeMeRIP-qPCR) were processed as just described for NeMeRIP-seq, but starting from 2.5x107 cells. MeRIP from cytoplasmic RNA was performed from RNA extracted from the cytoplasmic fraction of cells being processed for NeMeRIP. In both cases, MeRIP was performed as for NeMeRIP-seq, but using 2.5μg of anti m6A-antibody (or equivalent amounts of rabbit non-immune IgG) and 50μg of RNA in 500μl of BB supplemented with 500U of RNAsin ribonuclease inhibitor. At the end of the protocol, RNA was resuspended in 15μl of ultrapure RNAse-free water. For m6A MeRIP on total RNA, the protocol just described was followed exactly, with the exception that the subcellular fractionation step was bypassed, and that total RNA was extracted from 5x106 cells. For m6A MeRIP on mRNA, poly-A RNA was purified from 75μg of total RNA using the Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit, and 2.5μg of the resulting mRNA were used for chemical fragmentation and subsequent MeRIP with 1μg of anti-m6A antibody. At the end of all these protocols, cDNA synthesis was performed using all of the MeRIP material in a 30μl reaction containing 500ng random primers, 0.5mM dNTPs, 20U RNaseOUT, and 200U of SuperScript II (all from Invitrogen), all according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was diluted 10-fold, and 5μl were used for qPCR using KAPA Sybr Fast Low Rox (KAPA Biosystems). For each gene of interest, two primer pairs were designed either against the region containing the m6A peak23, or against a negative region (portion of the same transcript lacking the m6A peak; Supplementary Table 5). Results of MeRIP-qPCR for each gene were then calculated using the ΔΔCt approach by using the negative region to normalize both for the expression level of the transcript of interest and for background binding.

Analysis of NeMeRIP-seq data

QC of raw sequencing data was assessed using Trimmomatic v0.3546, with parameters ‘LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:5:10 MINLEN:40’. Reads were aligned to GRCh38 human genome assembly using TopHat 2.0.1347 with parameters ‘--library-type fr-firststrand –transcriptome-index’ and the Ensembl GRCh38.83 annotation. Identification of novel splice junctions was allowed. Paired-end and unpaired reads passing QC were concatenated and mapped in 'single-end' mode in order to be used with MeTDiff48, which only supports single-end reads. Reads with MAPQ<20 were filtered out. m6A peak calling and differential RNA methylation in the exome was assessed using MetDiff48 with pooled inputs for each conditions, GENE_ANNO_GTF=GRCh38.83, MINIMAL_MAPQ=20, and rest of parameters as default (PEAK_CUTOFF_FDR=0.05; DIFF_PEAK_CUTOFF_FDR=0.05). MetDiff calculates p-values by a likelihood ratio test, then adjust them to FDR by Benjamini-Hochberg correction. An additional cut-off of absolute fold-change>1.5 (meaning an absolute log2 fold-change>0.585) was applied for certain analyses as specified in the figure legends or tables. Given known differences between epitranscriptome maps as a function of pipeline49,50, we confirmed the site-specific and general trends in our data by using an additional pipeline45. For this, MACS251 was used with parameters ‘-q 0.05 --nomodel --keep-dup all’ in m6A NeMeRIP-seq and paired inputs after read alignment with Bowtie 2.2.2.0 (reads with MAPQ<20 were filtered out). Peaks found in at least two samples were kept for further processing, and a consensus MACS2 peak list was obtained merging those located in a distance closer than 100bp. The MetDiff and MACS2 peak lists largely overlapped (Extended Data Fig. 5d), and differed primarily because MACS2 identifies peaks throughout the genome while MetDiff only identifies peaks found on the exome (Extended Data Fig. 5c). For the following analyses focused on exonic m6A peaks we considered a stringent consensus list of only those MetDiff peaks overlapping with MACS2 peaks (Supplementary Table 2, “exon m6a”). We assessed the reproducibility of m6A NeMeRIP-seq triplicates in peak regions using the Bioconductor package fCCAC v1.0.052. Hierarchical clustering (euclidean distance, complete method) of F values corresponding to first two canonical correlations divided the samples in Activin and SB clusters. Normalized read coverage files were generated using the function 'normalise_bigwig' in RSeQC-2.653 with default parameters. The distribution of m6A coverage across genomic features was plotted using the Bioconductor package RCAS54 with sampleN=0 (no downsampling) and flankSize=2500. Motif finding on m6A peaks was performed using DREME with default parameters55. For visualization purposes, the three biological replicates were combined. The Biodalliance genome viewer56 was used to generate figures. Gene expression in this experiment was estimated from the pre-MeRIP input samples (which represent an RNA-seq sample on nuclear-enriched RNA species). Quantification, normalisation of read counts, and estimation of differential gene expression in pre-MeRIP input samples were performed using featureCounts57 and DESeq258. For assessment of reproducibility regularised log transformation of count data was computed, and biological replicates of input samples of the same condition clustered together in the PC space59. Estimation of differential m6A deposition onto each peak in NeMeRIP samples versus input controls was performed using an analogous approach. Functional enrichment analysis of m6A-marked transcripts was performed using Enrichr44, as described above for mass-spectrometry data. The coordinates of SMAD2/3 ChIP-seq peaks in hESCs30 were transferred from their original mapping on hg18 to hg38 using liftOver. Overlap of the resulting intervals with m6A peaks significantly downregulated after 2h of SB was determined using GAT60 with default parameters. SMAD2/3 binding sites were assigned to the closest gene using the annotatePeaks.pl function from the HOMER suite61 with standard parameters. The significance in the overlap between the resulting gene list and that of genes encoding for transcripts with m6A peaks significantly downregulated after 2h of SB was calculated by a hypergeometric test where the population size corresponded to the number of genes in the standard Ensemble annotation (GRCh38.83).

m6A peaks on introns were identified in three steps (Extended Data Fig 6d). First, MetDiff was used to simultaneously perform peak calling and differential methylation analysis. Since MetDiff only accepts a transcriptome GTF annotation as an input to determine the genomic space onto which it identifies m6A peaks, in order to determine peaks onto introns we followed the strategy recommended by the package developers of running the software using a custom transcriptome annotation that includes introns48,62. This “extended” transcriptome annotation was built using Cufflinks 2.2.163 with parameters '--library-type=fr-firststrand -m 100 -s 50’ and guided by the Ensemble annotation (GRCh38.83). This was assembled using all pre-NeMeRIP input reads available. The result was an extended transcriptome annotation including all of the transcribed genome that could be detected and reconstructed from our nuclear-enriched input RNA samples, thus including most expressed introns. Then, MetDiff was run using this extended annotation as input for GENE_ANNO_GTF, pooled inputs for each conditions, WINDOW_WIDTH=40, SLIDING_STEP=20, FRAGMENT_LENGHT=250, PEAK_CUTOFF_PVALUE=1E-03, FOLD_ENRICHMENT=2, MINIMAL_MAPQ=20, and all other parameters as default). In a second step, the peaks identified by MetDiff were filtered for robustness by requiring that they overlapped with MACS2 peak calls, exactly as for exome-focused MetDiff peak calls (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Finally, only peaks that strictly did not overlap with any exon based on the Human Gencode annotation V.27 were retained to ensure specificity of mapping to introns (Supplementary Table 2; “intron m6A”). MetDiff scores for the resulting peak list were used to assess differential m6A deposition based on the cutoff of FDR<0.05.

m6A exon peaks spanning splice sites were selected from those identified both by the MetDiff analysis on the transcribed genome that was just described and by MACS2. Among these peaks, those presenting sequencing reads overlapping to both an exon and upstream/downstream intron were further selected (Supplementary Table 2; “splice-site spanning m6A”). Peaks accomplishing MetDiff-calculated FDR<0.05 and absolute fold-change>1.5 (log2 fold-change<-0.585) were used to create densities of RPKM-normalized reads inside exons and in the ± 500bp surrounding introns. Biological replicates were merged and depicted on 10bp-binned heatmaps for visualization purposes. To study the covariation of m6A peaks inside each transcriptional unit, the exonic peak with the greatest down regulated MetDiff fold-change was compared to the mean fold-change of the rest of m6A peaks found within the gene (both on exons and on introns). The resulting correlation was significant (p<2E-16; adjusted R2=0.2221)

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

Polyadenylated (poly-A) purified opposing strand-specific mRNA library libraries were prepared from 200ng of total RNA using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA HT sample preparation kit (Illumina). Samples were individually indexed for pooling using a dual-index strategy. Libraries were quantified both with a Qubit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and by qPCR using the NGS Library Quantification Kit (KAPA Biosystems). Libraries were then normalized and pooled. Pooled libraries were diluted and denatured for sequencing on the NextSeq 500 (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were pooled so as to obtain >30M unique clusters per sample (18 samples were split in two runs and multiplexed across 4 lanes per run). The PhiX control library (Illumina) was spiked into the main library pool at 1% vol/vol for quality control purposes. Sequencing was performed using a high output flow cell with 2x75 cycles of sequencing, which provided ~800M paired end reads from ~400M unique clusters from each run. Overall, a total of ~80M paired end reads per sample were obtained.

Analysis of RNA-seq data

Reads were trimmed using Sickle64 with ‘q=20 and l=30’. To prepare for reads alignment, the human transcriptome was built with TopHat2 v2.1.044 based on Bowtie v2.2.665 by using the human GRCh38.p6 as reference genome, and the Ensembl gene transfer format (GTF) as annotation (http://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-83/gtf/homo_sapiens/). All analyses were performed using this transcriptome assembly. Alignment was performed using TopHat2 with standard parameters. Using Samtools view66, reads with MAPQ>10 were kept for further analyses. Subsequent quantitative data analysis was performed using SeqMonk67. The RNA-seq pipeline was used to quantify gene expression as reads per million mapped reads (RPM), and differential expression analysis for binary comparisons was performed using the R package DESeq258. A combined cut-off of negative binomial test p<0.05 and abs.FC>2 was chosen. Analysis of differentially expressed transcripts across all samples was done using the R/Bioconductor timecourse package68. The Hotelling T2 score for each transcript was calculated using the MB.2D function with all parameters set to their default value. Hotelling T2 scores were used to rank probes according to differential expression across the time-course, and the top 5% differentially expressed transcripts were selected for complete Euclidean hierarchical clustering (k-means preprocessing; max of 300 clusters) using Perseus software. Z-scores of log2 normalized expression values across the timecourse were calculated and used for this analysis. 8 gene clusters were defined, and gene enrichment analysis for selected clusters was performed using the Fisher’s exact test implemented in Enrichr44. Only enriched terms with a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value<0.05 were considered. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the same list of top 5% differentially expressed transcripts using Perseus.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Cellular RNA was extracted using the GenElute Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit and the On-Column DNase I Digestion Set (both from Sigma-Aldrich) following manufacturer’s instructions. 500ng of RNA was used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis using SuperScript II (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was diluted 30-fold, and 5μl were used for qPCR using SensiMix SYBR low-ROX (Bioline) and 150nM forward and reverse primers (Sigma-Aldrich; see Supplementary Table 5 for primer sequences). Samples were run in technical duplicates on 96-well plates on a Stratagene Mx-3005P (Agilent), and results were analysed using the delta-delta cycle threshold (ΔΔCt) approach69 using RPLP0 as housekeeping gene. The reference sample used as control to calculate the relative gene expression is indicated in each figure or figure legend. In cases where multiple control samples were used as reference, the average ΔCt from all controls was used when calculating the ΔΔCt. All primers were designed using PrimerBlast (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/), and were validated to have a qPCR efficiency >98% and to produce a single PCR product.

mRNA stability measurements

RNA stability was measured by collecting RNA samples at different time points following transcriptional inhibition with 1 μg/ml actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich). Following qPCR analyses using equal amounts of mRNA, gene expression was expressed as relative to the beginning of the experiment (no actinomycin D treatment). The data was then fit to a one-phase decay regression model70, and statistical differences in mRNA half-live were evaluated by comparing the model fits by extra sum-of-squares F test.

Western blot

Samples were prepared by adding Laemmli buffer (final concentration of 30mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 6% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate/SDS, 0.02% bromophenol blue, and 0.25% β-mercaptoethanol), and were denatured at 95°C for 5’. Proteins were loaded and run on 4-12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris Precast Gels (Invitrogen), then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes by liquid transfer using NuPAGE Transfer buffer (Invitrogen). Membranes were blocked for 1h at RT in PBS 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) supplemented with 4% non-fat dried milk, and incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody diluted in the same blocking buffer (Supplementary Table 6). After three washes in PBST, membranes were incubated for 1h at RT with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer (Supplementary Table 6), then further washed three times with PBST before being incubated with Pierce ECL2 Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo) and exposed to X-Ray Super RX Films (Fujifilm).

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed for 20’ at 4°C in PBS 4% PFA, rinsed three times with PBS, and blocked and permeabilized for 30’ at RT using PBS with 10% donkey serum (Biorad) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 6) were diluted in PBS 1% donkey serum 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight at 4°C. This was followed by three washes with PBS and by further incubation with AlexaFluor secondary antibodies (Supplementary Table 6) for 1h at RT protected from light. Cells were finally washed three times with PBS, and 4′,6-Diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the first wash to stain nuclei. Images were acquired using a LSM 700 confocal microscope (Leica).

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions were prepared by incubation in cell cell dissociation buffer (CDB; Gibco) for 10’ at 37° followed by extensive pipetting. Cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed for 20’ at 4°C with PBS 4% PFA. After three washes with PBS, cells were first permeabilized for 20’ at RT with PBS 0.1% Triton X-100, then blocked for 30’ at RT with PBS 10% donkey serum. Primary and secondary antibodies incubations (Supplementary Table 6) were performed for 1h each at RT in PBS 1% donkey serum 0.1% Triton X-100, and cells were washed three times with this same buffer after each incubation. Flow cytometry was performed using a Cyan ADP flow-cytometer, and at least 10,000 events were recorded. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo X.

Statistics and reproducibility

Unless described otherwise in a specific section of the Methods, standard statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 using default parameters. The type and number of replicates, the statistical test used, and the test results are described in the figure legends. The level of significance in all graphs is represented as it follows (p denotes the p-value): *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, and ***=p<0.001. Test assumptions (e.g. normal distribution) were confirmed where appropriate. For analyses with n<10 individual data points are shown, and the mean ± SEM is reported for all analyses with n>2. The mean is reported when n=2, and no other statistics were calculated for these experiments due to the small sample size. No experimental samples were excluded from the statistical analyses. Sample size was not pre-determined through power calculations, and no randomization or investigator blinding approaches were implemented during the experiments and data analyses. When representative results are presented, the experiments were reproduced in at least two independent cultures, and the exact number of such replications is detailed in the figure legend.

Code availability

Custom bioinformatics scripts used to analyse the data presented in the study have been deposited to GitHub (http://github.com/pmb59/neMeRIP-seq).

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data that support the findings of this study have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the identifier PXD005285. Nucleotide sequencing data that support the findings of this study have been deposited to Array Express with identifiers E-MTAB-5229 and E-MTAB-5230. Source data for the graphical representations found in all Figures and Extended Data Figures are provided in the Supplementary Information of this manuscript (Source Data Table Figure 1 and 3, and Source Data Extended Data Figure 1 to 10). Electrophoretic gel source data (uncropped scans with size marker indications) are presented in Supplementary Figure 1. Supplementary Tables 1 to 4 provide the results of bioinformatics analyses described in the text and figure legends. All other data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Extended Data

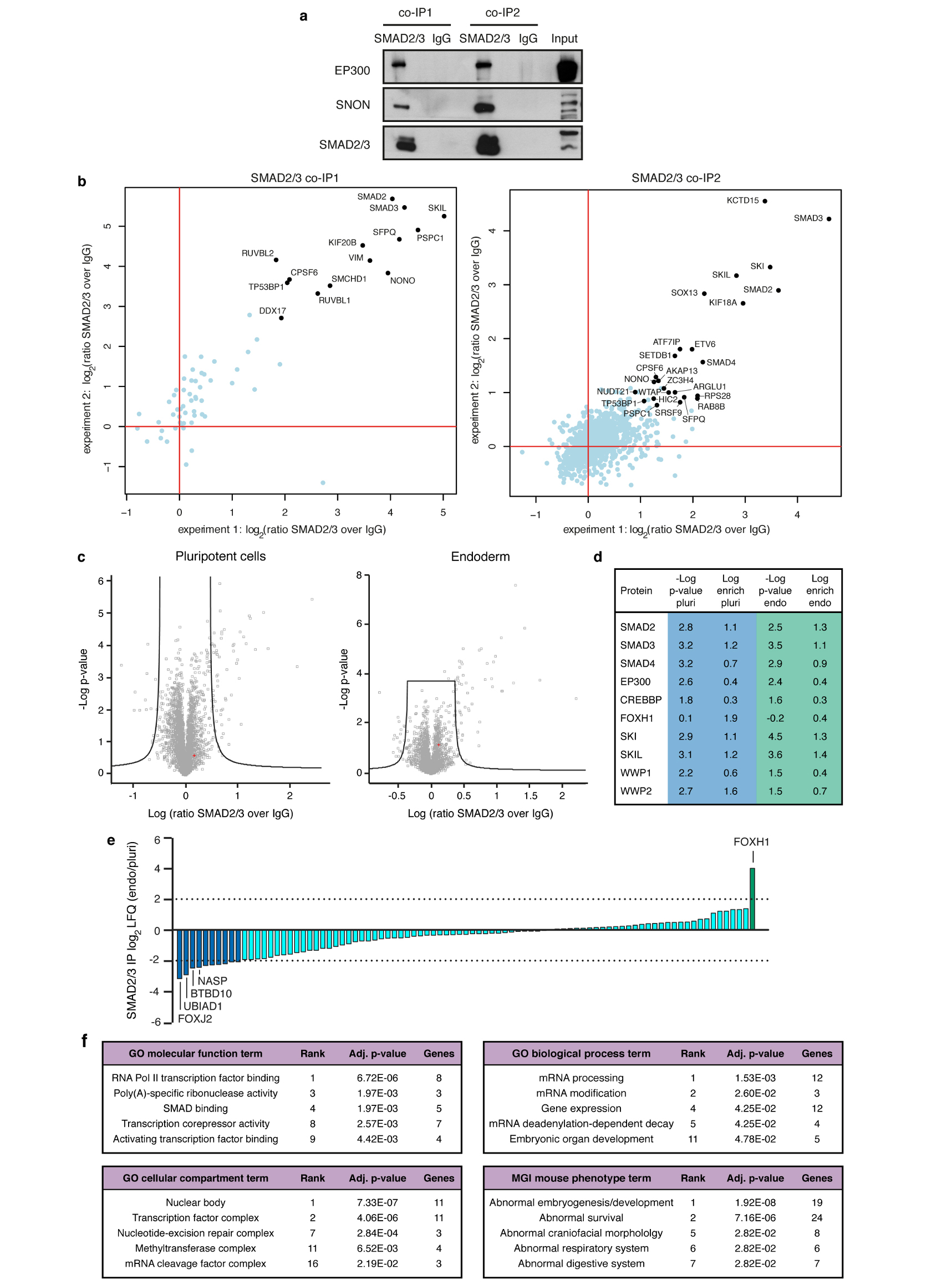

Extended Data Figure 1. Optimized SMAD2/3 co-immunoprecipitation protocol to define its interactome in hPSCs and early endoderm cells.

(a) Western blots of SMAD2/3 or control (IgG) immunoprecipitations (IPs) from nuclear extracts of hESCs following the co-IP1 or co-IP2 protocols. Input is 5% of the material used for IP. Results are representative of two independent experiments. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1. (b) Scatter plots of the log2 ratios of label-free quantification (LFQ) intensities for proteins identified by quantitative mass spectrometry in SMAD2/3 co-IPs compared with IgG negative control co-IPs. The experiments were performed from nuclear extracts of hESCs. The SMAD2/3 and IgG negative control co-IPs were differentially labelled post-IP using the dimethyl method, followed by a combined run of the two samples in order to compare the abundance of specific peptides and identify enriched ones. The values for technical dye-swap duplicates are plotted on different axes, and proteins whose enrichment was significant (significance B<0.01) are shown in black and named. As a result of this comparison between the two co-IP protocols, co-IP2 was selected for further experiments (see Supplementary Discussion). (c) Volcano plots of statistical significance against fold-change for proteins identified by label-free quantitative mass spectrometry in SMAD2/3 or IgG negative control IPs in pluripotent hESCs or early endoderm (see Fig. 1a). The black lines indicate the threshold used to determine specific SMAD2/3 interactors, which are located to the right (n=3 co-IPs; one-tailed t-test: permutation-based FDR<0.05). (d) Selected results of the analysis described in panel c for SMAD2, SMAD3, and selected known bona fide SMAD2/3 binding partners (full results can be found in Supplementary Table 1). (e) Average label free quantification (LFQ) intensity log2 ratios in endoderm (Endo) and pluripotency (Pluri) for all SMAD2/3 interactors. Differentially enriched proteins are shown as green and blue bars. (f) Selected results from gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, and enrichment analysis for mouse phenotypes annotated in the Mouse Genomics Informatics (MGI) database. All SMAD2/3 putative interacting proteins were considered for this analysis (n=89 proteins; Fisher’s exact test followed by Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisions). For each term, its rank in the analysis, the adjusted p-value, and the number of associated genes are reported.

Extended Data Figure 2. Functional characterization of SMAD2/3 transcriptional and epigenetic cofactors in hPSCs.

(a) Western blots of SMAD2/3 or control (IgG) immunoprecipitations (IPs) from nuclear extracts of pluripotent hESCs (Pluri), or hESCs differentiated into endoderm for 36h (Endo). Input is 5% of the material used for IP. Results are representative of two independent experiments. (b) Schematic of the experimental approach for the generation of tetracycline-inducible knockdown (iKD) hESC lines for SMAD2/3 cofactors. (c) qPCR screening of iKD hESCs cultured in absence (CTR) or presence of tetracycline for 3 days (TET). Three distinct shRNAs were tested for each gene. Expression is shown as normalized on the average level in hESCs carrying negative control shRNAs (scrambled, SCR, or against B2M) and cultured in absence of tetracycline. The mean is indicated, n=2 independent clonal pools. Note than for the B2M shRNA only the SCR shRNA was used as negative control. shRNAs selected for further experiments are circled. (d) Phase contrast images of iKD hESCs expressing the indicated shRNAs (sh) and cultured in presence of tetracycline for 6 days to induce knockdown. Scale bars: 400μm. Results are representative of two independent experiments. (e) Immunofluorescence for the pluripotency factor NANOG in iKD hESCs for the indicated genes cultured in absence (CTR) or presence of tetracycline (TET) for 6 days. DAPI: nuclear staining; scale bars: 400μm. Results are representative of two independent experiments. (f) Heatmap summarizing qPCR analyses of iKD hESCs cultured as in panel e. log2 fold-changes (FC) are compared to SCR CTR (n=2 clonal pools). Germ layer markers are grouped in boxes (green: endoderm; red: mesoderm; blue: neuroectoderm).

Extended Data Figure 3. Functional characterization of SMAD2/3 transcriptional and epigenetic cofactors during endoderm differentiation.

(a) qPCR validation of inducible knockdown (iKD) hESCs in pluripotency (PLURI) and following endoderm differentiation (ENDO). Pluripotent cells were cultured in absence (CTR) or presence of tetracycline (TET) for 6 days. For endoderm differentiation, tetracycline treatment was initiated in undifferentiated hESCs for 3 days in order to ensure gene knockdown at the start of endoderm specification, and was then maintained during differentiation (3 days). For each gene, the shRNA resulting in the strongest level of knockdown in hPSCs was selected (refer to Extended Data Fig. 2). Expression is shown as normalized to the average level in pluripotent hESCs carrying a scrambled (SCR) control shRNAs and cultured in absence of tetracycline. The mean is indicated, n=2 independent clonal pools. (b) Immunofluorescence for the endoderm marker SOX17 following endoderm differentiation of iKD hESCs expressing the indicated shRNAs (sh) and cultured as described in panel a. DAPI shows nuclear staining. Scale bars: 400μm. Results are representative of two independent experiments. (c) qPCR following endoderm differentiation of iKD hESCs. The mean is indicated, n=2 independent clonal pools. (d) Table summarizing the phenotypic results presented in Extended Data Fig. 2 and in this figure. E: endoderm; N: neuroectoderm; M: mesoderm.

Extended Data Figure 4. Mechanistic insights into the functional interaction between SMAD2/3 and the m6A methyltransferase complex.

(a-c) Western blots of SMAD2/3 (S2/3), METTL3 (M3), METTL14 (M14), or control (IgG) immunoprecipitations (IPs) from nuclear extracts of hPSCs (hESCs for panels a and c, and hiPSCs for panel b). Input is 5% of the material used for IP. In c, IPs were performed from hPSCs maintained in presence of Activin or treated for 1h with the Activin/Nodal inhibitor SB-431542 (SB). Results are representative of three (panel a) or two (panels b-c) independent experiments. (d) qPCR validation of hESCs constitutively overexpressing NANOG (NANOG OE) following gene targeting of the AAVS1 locus with pAAV-Puro_CAG-NANOG. Parental wild-type H9 hESCs (H9) were analysed as negative control. Cells were cultured in presence of Activin or treated with SB for the indicated time points. The mean is indicated, n=2 cultures. NANOG OE cells are resistant to downregulation of NANOG following Activin/Nodal inhibiton. (e) RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments for WTAP, SMAD2/3 (S2/3), or IgG control in NANOG overexpressing hESCs maintained in presence of Activin or treated for 2 hours with SB. Enrichment of the indicated transcripts was measured by qPCR and expressed over background levels observed in IgG RIP in presence of Activin. RPLP0 was tested as a negative control transcript. Mean ± SEM, n=3 cultures. Significance was tested for differences versus Activin (left panel) or versus IgG (right panel) by 2-way ANOVA with post-hoc Holm-Sidak comparisons: *=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, and ***=p<0.001. (f) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) qPCR in hESCs for the indicated proteins or for the negative control ChIP (IgG). qPCR was performed for validated genomic SMAD2/3 binding sites associated to the indicated genes10,30. hESCs were cultured in presence of Activin or treated for 2h with SB. The enrichment is expressed as normalized levels to background binding observed in IgG ChIP. The mean is indicated, n=2 technical replicates. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 5. Monitoring the changes in m6A deposition rapidly induced by Activin/Nodal inhibition.

(a-b) m6A methylated RNA immunoprecipitation (MeRIP) qPCR results from purified mRNA, total cellular RNA, or cellular RNA species separated following nuclear/cytoplasmic subcellular fractionation. hESCs were cultured in pluripotency-maintaining conditions containing Activin, or subjected to Activin/Nodal inhibition for 2h with SB-431542 (SB). IgG MeRIP experiments were performed as negative controls. The mean is indicated, n=2 technical replicates. Differences between Activin and SB-treated cells were observed only in the nuclear-enriched fraction. Therefore, the nuclear-enriched MeRIP protocol (NeMeRIP) was used for subsequent experiments (refer to the Supplementary Discussion). Results are representative of two independent experiments. (c) Overlap with the indicated genomic features of m6A peaks identified by NeMeRIP-seq using two different bioinformatics pipelines in which peak calling was performed using MetDiff or MACS2. For each pipeline, the analyses were performed on the union of peaks identified from data obtained in hESCs cultured in presence of Activin or subjected to Activin/Nodal inhibition for 2h with SB (n=3 cultures). Note that the sum of the percentages within each graph does not add to 100% because some m6A peaks overlap several feature types. MetDiff is an exome peak caller, and accordingly 100% of peaks map to exons. MACS2 identifies peaks throughout the genome. (d) Venn diagrams showing the overlap of peaks identified by the two pipelines. Only MetDiff peaks that were also identified MACS2 were considered for subsequent analyses focused on m6A peaks on exons. (e) Top sequence motifs identified de novo on all m6A exon peaks, or on such peaks that showed significant downregulation following Activin/Nodal inhibition (Activin/Nodal-sensitive m6A peaks; Supplementary Table 2). The position of the methylated adenosine is indicated by a box. (f) Coverage profiles for all m6A exon peaks across the length of different genomic features. Each feature type is expressed as 100 bins of equal length with 5’ to 3’ directionality. (g-h) Overlap of m6A exon peaks to transcription start sites (TSS) or transcription end sites (TES). In g, the analysis was performed for all m6A peaks. In h, only Activin/Nodal-sensitive peaks were considered. (i) On the left, Activin/Nodal-sensitive m6A exon peaks were evaluated for direct overlap with SMAD2/3 binding sites measured by ChIP-seq30. n=482 peaks; FDR=0.41 (non-significant at 95% confidence interval, N.S.) as calculated by the permutation test implemented by the GAT python package. On the right, overlap was calculated after the same features were mapped to their corresponding transcripts or genes, respectively. A significant overlap was observed for the transcript-gene overlap. n=372 genes; hypergeometric test p-value (p) of 2.88E-18, significant at 95% confidence interval. (j) m6A NeMeRIP-seq results for selected transcripts (n=3 cultures; replicates combined for visualization). Coverage tracks represent read-enrichments normalized by million mapped reads and size of the library. Blue: sequencing results of m6A NeMeRIP. Orange: sequencing results of pre-NeMeRIP input RNA (negative control). GENCODE gene annotations are shown (red: protein coding exons; white: untranslated exons; note that all potential exons are shown and overlaid). The location of SMAD2/3 ChIP-seq binding sites is also reported. Compared to the other genes shown, the m6A levels on SOX2 were unaffected by Activin/Nodal inhibition, showing specificity of action. OCT4/POU5F1 is reported as negative control since it is known not to have any m6A site23, as confirmed by the lack of m6A enrichment compared to the input.

Extended Data Figure 6. Features of Activin/Nodal-sensitive differential m6A deposition.