Abstract

Background

The LAP07 randomized trial calls into question the role of radiation therapy (RT) in the modern treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC). However, advances in chemotherapy and RT limit application of the LAP07 results to current clinical practice. Here we utilize the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to evaluate the effects of RT in patients receiving chemotherapy for LAPC.

Methods

Using the NCDB, patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) clinical stage T2–4, N0–1, M0 adenocarcinoma of the pancreas from 2004 to 2014 were analyzed. Patients were stratified into chemotherapy only (CT) and chemoradiation (CRT) cohorts. Patients undergoing definitive RT, defined as at least 20 fractions or ≥≥ 5 Gy per fraction [i.e., stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)] were included in the CRT cohort. Propensity-score matching (PSM) and landmark analysis were used to address selection bias and lead-time bias, respectively.

Results

13,004 patients met inclusion criteria, of whom 7034 (54%) received CT and 5970 (46%) received CRT. After PSM, 5215 patients remained in each cohort. The CRT cohort demonstrated better overall survival (OS) compared with CT alone, with median and 1-year OS of 12 versus 10 months, and 50% and 41%, respectively (p << 0.001). On multivariable analysis, CRT was associated with superior OS with hazard ratio of 0.79 (95% confidence interval 0.76–0.83) compared with CT alone.

Conclusions

In our series, addition of definitive radiotherapy to CT was associated with better OS when compared with CT alone in LAPC. Definitive radiotherapy should remain a treatment option for LAPC, but optimal selection criteria remain unclear.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is an aggressive malignancy and represents the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the USA.1 While radical resection with pancreatoduodenectomy remains the only curative treatment, only 10–12% of patients are diagnosed with potentially resectable disease, and just a portion of these patients achieve margin-negative (R0) resection.2–4 For the remaining patients diagnosed with locally advanced, unresectable disease, median survival is a dismal 12–15 months, despite aggressive multidisciplinary care.1,2

Historical randomized data by the Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group established the role of multimodality therapy with radiation therapy (RT) and chemotherapy for locally advanced tumors.5,6 The recently published LAP-07 trial challenged the role of RT; addition of RT improved local control without demonstrable benefits in overall survival.7 However, the LAP-07 trial utilized single-agent gemcitabine chemotherapy with conventionally fractionated RT. Recent randomized data demonstrate that, compared with gemcitabine alone, multiagent chemotherapy prolongs survival in advanced pancreatic cancer.8,9 Additionally, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) has recently been utilized by many institutions in treatment of LAPC, with emerging data suggesting greater local control, decreased toxicity, and better overall survival compared with conventionally fractionated RT.10–14

To date, there have been no large, phase III studies investigating the benefit of modern radiation therapy in the setting of multiagent systemic therapy. Here we utilized the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to investigate and compare outcomes in patients with LAPC treated with chemotherapy with and without definitive radiation therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Cohorts

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) registry was queried for patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2014 with pancreatic cancer. The period of 2004–2014 was chosen to include patients who received both single- and multiagent chemotherapy to compare the effects of RT among these two groups of patients. The NCDB is a joint program of the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society which includes approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed malignancies in the USA.15,16 The database contains parameters not included in other large national registries, such as detailed radiotherapy information regarding treatment area, radiation dose, and number of radiation fractions. Since no patient or physician identifiers are provided, this study was granted exempt status by the Emory Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Only patients whose first and only cancer diagnosis was pancreatic adenocarcinoma were analyzed. Those patients with histologically confirmed American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) clinical tumor stage 2–4 and nodal stage 0–1 were included. Only tumors in the pancreatic head and/ or body were included; tumors in the tail of the pancreas were excluded, as these are typically treated with distal pancreatectomy and may have dissimilar outcomes.17 Patients were included if and only if they were documented to receive chemotherapy and did not receive radical resection. All cases with metastatic disease were excluded.

Patients were grouped into the chemoradiation cohort based on whether they were documented to have received definitive RT. Both conventionally fractionated regimens of ≥ 20 radiation fractions and SBRT regimens of ≥ 5 Gy per fraction were included; brachytherapy was excluded. Patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and treatment details were also ascertained from the NCDB, including age at diagnosis, gender, AJCC clinical tumor–node– metastasis (TNM) staging, tumor size (largest axial dimension), Charlson–Deyo comorbidity score, chemotherapy use, and year of diagnosis.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were compiled to summarize patient, disease, and treatment characteristics. Associations of the patient and other cancer-related variables were tested by Pearson’s Chi square test (χχ2) and analysis of variance (ANOVA), for categorical and numeric variables, respectively. Overall survival was defined as time from diagnosis to death or last follow-up, where those alive were censored at last follow-up. Univariate association of patient or disease characteristics with overall survival was assessed using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were fit for overall survival. The collinearity among all baseline patients and disease characteristics was verified by calculating variance inflation factors (VIF). Variables with VIF [ 10 were not considered in multivariable analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 with software macros generated at Winship Cancer Institute’s Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics.18

To minimize treatment selection bias, a propensity-score matching method was used. The covariates chosen were ones found to be significant on multivariable analysis or ones thought to be clinically relevent. Patients from each study cohort were matched to each other at 1:1 ratio based on the propensity score using a greedy 5-1 digit match algorithm; after matching, the balance of covariate between two cohorts was evaluated by the standardized differences and a value < 0.1 was considered as negligible imbalance.19 The effects were estimated in the matched sample using a Cox model with a robust variance estimator for overall survival.20

To account for possible guarantee-time bias, a conditional landmark analysis was employed.21 The purpose of the landmark analysis was to adjust for possible bias from excluding patients in the CRT cohort if they had died prior to receiving radiation therapy and only selecting for patients who lived long enough to receive RT. The landmark time was chosen to be the median time to starting radiation therapy from date of diagnosis, which was 54 days. Accordingly, all patients who died prior to the landmark time were excluded from analysis in the guarantee-time bias.

RESULTS

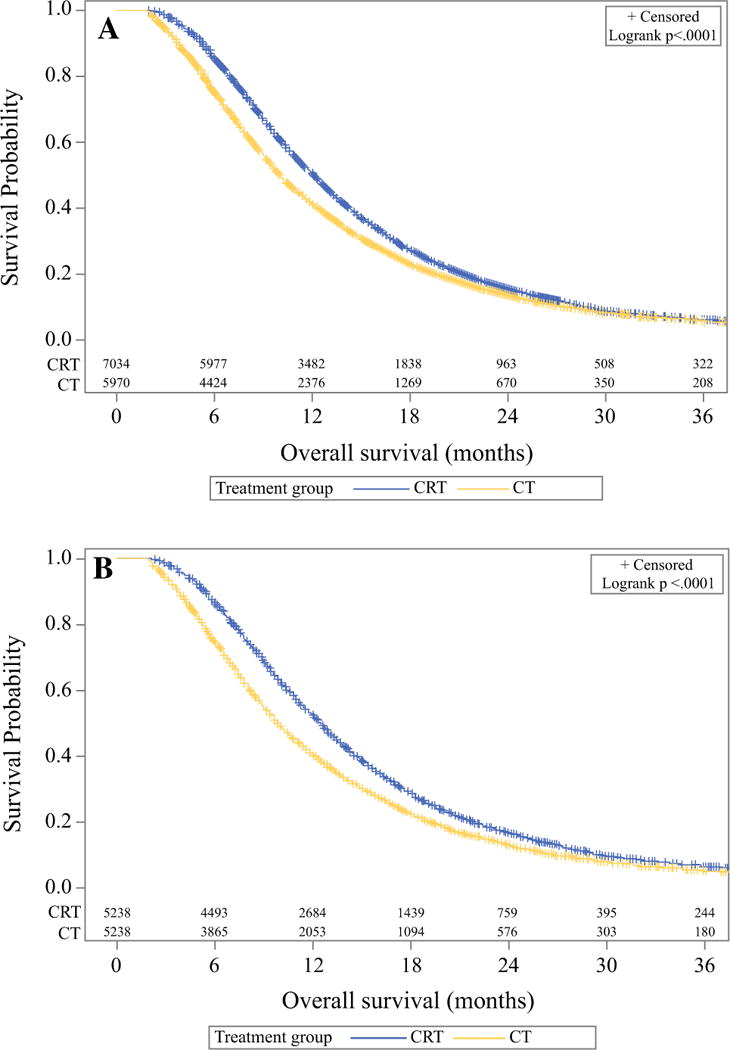

A total of 17,610 patients with pancreatic head or body ductal adenocarcinoma, who met inclusion criteria were identified from the NCDB between 2004 and 2014 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Of these 17,610 patients, 7785 (44%) received chemoradiation (CRT) and 7400 (56%) received chemotherapy only (CT). A total of 2181 patients were removed from analysis as a result of the lead-time bias adjustment. Patient and tumor characteristics by cohort are presented in Table 1. Most notably, the CRT cohort contained a higher proportion of T4 tumors (52.8% vs. 49.1%), smaller tumor size (mean 3.9 vs. 4.1 cm), higher proportion of node-negative patients (63.1% vs. 60.0%), higher proportion of patients receiving single-agent CT (58.9% vs. 46.0%), and higher proportion of patients with Charlson– Deyo score of 0 (71.4% vs. 69.2%) (all p < 0.05). Additionally, a lower proportion of CRT patients were treated most recently from 2012 to 2014 compared with CT (23.2% vs. 32.0%, p < 0.001). There were also minor differences in age, sex, treatment facility type, and insurance status (all p < 0.05). Kaplan–Meier curves for the two cohorts are displayed in Fig. 1a and demonstrate a 2-year OS of 13.4% versus 15.5% for the CT and CRT groups, respectively (p < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Patient and disease characteristics

| Covariate | CRT (n = 7034) | CT (n = 5970) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Median | 65 | 67 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3573 (50.8) | 2854 (47.81) | 0.002 |

| Female | 3461 (49.2) | 3116 (52.19) | |

| AJCC clinical T | |||

| 2 | 978 (13.9) | 892 (14.94) | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 2340 (33.27) | 2145 (35.93) | |

| 4 | 3716 (52.83) | 2933 (49.13) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| Mean | 3.94 | 4.08 | 0.017 |

| Median | 3.6 | 3.7 | |

| AJCC clinical N | |||

| 0 | 4436 (63.07) | 3580 (59.97) | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 2598 (36.93) | 2390 (40.03) | |

| Chemotherapy agent | |||

| Single-agent chemotherapy | 4140 (58.86) | 2744 (45.96) | < 0.001 |

| Multiagent chemotherapy | 2578 (36.65) | 2867 (48.02) | |

| 316 (4.49) | 359 (6.01) | ||

| Facility type | |||

| Community cancer program | 573 (8.21) | 350 (5.91) | < 0.001 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 2694 (38.6) | 1983 (33.46) | |

| Academic/research program | 3045 (43.62) | 2995 (50.54) | |

| Integrated network cancer program | 668 (9.57) | 598 (10.09) | |

| Insurance status | |||

| Not insured | 2776 (39.96) | 189 (3.21) | 0.017 |

| Private insurance | 417 (6) | 2078 (35.32) | |

| Medicaid/Medicare/other government | 4001 (57.59) | 3616 (61.47) | |

| Charlson–Deyo Score | |||

| 0 | 5026 (71.45) | 4129 (69.16) | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 1589 (22.59) | 1452 (24.32) | |

| 2 | 419 (5.96) | 389 (6.52) | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004–2005 | 963 (13.69) | 579 (9.7) | < 0.001 |

| 2006–2007 | 1267 (18.01) | 829 (13.89) | |

| 2008–2009 | 1555 (22.11) | 1273 (21.32) | |

| 2010–2011 | 1616 (22.97) | 1378 (23.08) | |

| 2012–2014 | 1633 (23.22) | 1911 (32.01) | |

| Distance from center | |||

| Mean | 38.26 | 37.19 | 0.64 |

| Median | 10.9 | 11.8 |

FIG. 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrating overall survival for unmatched cohorts (a) and propensity-matched cohorts (b)

Radiation Therapy

Median time to receipt of RT from diagnosis for the CRT cohort was 54 days, which was used as the conditional landmark time to adjust for guarantee-time bias. The median follow-up time was 22.6 months. Of the 7013 patients who received CRT, 435 (6.2%) patients underwent SBRT dosing, and 6578 (93.8%) patients underwent conventionally fractionated radiation dosing. For the CRT cohort, the median fractionated RT dose was 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions (5–95th percentile: 1.6–2.1 Gy in 24–33 fractions) and median SBRT dose was 24 Gy in 3 fractions (5–95th percentile: 5–25 Gy per fraction in 1–5 fractions).

Multivariable Analysis

On multivariable analysis (Table 2), treatment with CRT was associated with significantly longer OS with hazard ratio (HR) of 0.79 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76–0.83, p < 0.001]. Within the CRT cohort, the subset of patients receiving SBRT demonstrated the lowest hazard ratio compared with CT alone: 0.71 (95% CI 0.64–0.80) versus 0.80 (95% CI 0.77–0.84), respectively, for SBRT and conventional fractionation. Additionally, treatment with multiagent chemotherapy compared with single-agent chemotherapy (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.68–0.74), treatment at an academic/research program compared with an integrated network program (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85–0.98)), private insurance status compared with not insured (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74–0.97), and Charlson–Deyo score of 0 compared with 2 + (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77–0.92) were associated with longer OS. As expected, larger tumor size (HR 1.01, HR 1.01–1.02) and node-positive disease (HR 1.09, 95% CI 1.05–1.14) were associated with significantly worse survival.

TABLE 2.

Multivariable analysis of patient and disease characteristics on overall survival

| Covariate | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment group | ||

| CRT (all RT techniques) | 0.79 (0.76–0.83) | < 0.001 |

| Conventionally fractionated RT | 0.80 (0.77–0.84) | < 0.001 |

| SBRT | 0.71 (0.64–0.80) | < 0.001 |

| CT | – | – |

| Facility type | ||

| Community cancer program | 1.06 (0.95–1.17) | 0.297 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) | 0.302 |

| Academic/research program | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 0.011 |

| Integrated network cancer program | – | – |

| Tumor size (cm) | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.05 (1.00–1.09) | 0.036 |

| Female | – | – |

| Insurance status | ||

| Not insured | – | – |

| Private insurance | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) | 0.014 |

| Medicaid/Medicare/other government | 0.95 (0.83–1.08) | 0.419 |

| Charlson–Deyo score | ||

| 0 | 0.84 (0.77–0.92) | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 0.91 (0.83–1.00) | 0.047 |

| 2 | – | – |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2006–2007 | 1.27 (1.19–1.35) | < 0.001 |

| 2008–2009 | 1.22 (1.15–1.29) | < 0.001 |

| 2010–2011 | 1.09 (1.04–1.16) | 0.001 |

| 2012–2014 | – | – |

| 2004–2005 | – | – |

| AJCC clinical N | ||

| 1 | 1.09 (1.05–1.14) | < 0.001 |

| 0 | – | – |

| Age at diagnosis | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | < 0.001 |

| Chemotherapy agent(s) | ||

| Single-agent chemotherapy | – | – |

| Multiagent chemotherapy | 0.71 (0.68–0.74) | < 0.001 |

| Unspecified agent(s) | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | 0.145 |

Propensity-Matched Outcomes

Following propensity-score matching, a total of 10,430 patients remained, with 5215 patients in each cohort. Table 3 displays the propensity-matched patient and disease characteristics for the following variables which met significance threshold on univariate analysis: patient age, AJCC clinical tumor and nodal stages, tumor size, Charl-son–Deyo score, year of diagnosis, insurance status, chemotherapy type, and treatment facility type. All stan-dardized differences for patient and disease characteristics were < 0.1, indicating adequate propensity matching. After propensity-score matching, CRT continued to be associated with significantly longer OS compared with CT alone, with median OS of 12.3 (95% CI 21.1–12.6) months versus 9.8 (95% CI 9.6–10.1) months and 2-year OS rates of 16.3% (15.3–17.3%) versus 12.9% (12.0–13.9%), respectively (p < 0.001). The propensity-matched Kaplan–Meier curves are depicted in Fig. 1b.

TABLE 3.

Patient and disease characteristics of propensity-matched cohorts

| Covariate | CRT (n = 5215) | Chemo only (n = 5215) | Standardized difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| Mean (Std) | 66.76 (10.36) | 66.56 (10.83) | 0.019 |

| AJCC clinical T | |||

| 2 | 772 (14.8) | 763 (14.63) | 0.005 |

| 3 | 1824 (34.98) | 1813 (34.77) | 0.004 |

| 4 | 2619 (50.22) | 2639 (50.6) | 0.008 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| Mean (Std) | 3.95 (3.12) | 4.08 (3.44) | 0.041 |

| AJCC clinical N | |||

| 0 | 3211 (61.57) | 3194 (61.25) | 0.007 |

| 1 | 2004 (38.43) | 2021 (38.75) | 0.007 |

| Charlson–Deyo score | |||

| 0 | 3648 (69.95) | 3646 (69.91) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 1227 (23.53) | 1241 (23.8) | 0.006 |

| 2 | 340 (6.52) | 328 (6.29) | 0.009 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004–2005 | 570 (10.93) | 541 (10.37) | 0.018 |

| 2006–2007 | 777 (14.9) | 777 (14.9) | 0 |

| 2008–2009 | 1131 (21.69) | 1140 (21.86) | 0.004 |

| 2010–2011 | 1254 (24.05) | 1246 (23.89) | 0.004 |

| 2012–2014 | 1483 (28.44) | 1511 (28.97) | 0.012 |

| Insurance status | |||

| Not insured | 138 (2.65) | 139 (2.67) | 0.001 |

| Private insurance | 332 (6.37) | 324 (6.21) | 0.006 |

| Medicaid/Medicare/other government | 4745 (90.99) | 4752 (91.12) | 0.005 |

| Chemotherapy type | |||

| Chemotherapy administered, type and number of agents not documented | 279 (5.35) | 271 (5.2) | 0.007 |

| Single-agent chemotherapy | 2628 (50.39) | 2609 (50.03) | 0.007 |

| Multiagent chemotherapy | 2308 (44.26) | 2335 (44.77) | 0.01 |

| Facility type | |||

| Community cancer program | 327 (6.27) | 335 (6.42) | 0.006 |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 1886 (36.16) | 1825 (35) | 0.024 |

| Academic/research program | 2511 (48.15) | 2533 (48.57) | 0.008 |

| Integrated network cancer program | 491 (9.42) | 522 (10.01) | 0.02 |

Subset Analysis

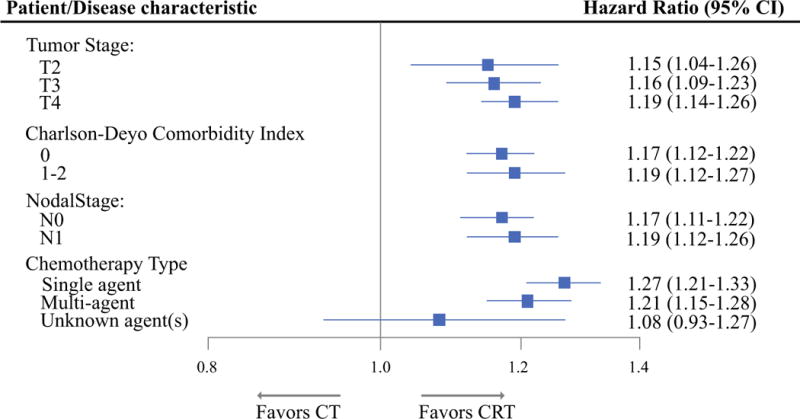

Figure 2 demonstrates multivariable subgroup analysis of patient and disease characteristics on OS comparing CT and CRT. For all subsets of AJCC tumor and nodal staging as well as all Charlson–Deyo comorbidity scores, CRT was significantly favored over CT. For CT type, both single-agent and multiagent chemotherapy use strongly favored CRT (HR 1.27, 95% CI 1.21–1.33) and 1.21 (95% CI 1.15–1.28), respectively. Other than those with unknown chemotherapy agent, all subgroups of patients appeared to benefit from CRT over CT. When analysis was restricted to patients with T4 disease, overall survival was still longer in the CRT arm (HR 1.19, 95% CI 1.14–1.26).

FIG. 2.

Multivariable subgroup analyses of patient demographics, disease characteristics, and treatment details on OS comparing CT and CRT

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to compare outcomes in patients with locally advanced, unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with CT with or without RT. Our data demonstrate that patients treated with CRT demonstrated a significant OS benefit over those who received chemotherapy alone. The survival benefit remained after propensity matching for key patient and disease characteristics known to impact prognosis, as well as those independently found on our multivariable analysis to affect survival. Additionally, our data demonstrate a significant survival advantage for CRT despite adjustment for possible guarantee-time bias for those patients receiving radiation. Among the patients who received CRT in this analysis, those who received SBRT appeared to have the longest overall survival.

Our series represents the first to directly investigate the effects of RT combined with chemotherapy in LAPC treated with both modern radiation and chemotherapy. We included patients treated with SBRT in addition to chemotherapy in our analysis given the increasing popularity of this treatment. While the SBRT subset of patients appeared to perform most favorably, inherent differences in tumor anatomy in those patients eligible for SBRT should be taken into consideration. The historic GITSG study, which demonstrated a survival benefit when RT was added to chemotherapy, utilized a split-course conventionally fractionated RT regimen that is rarely utilized today.6 The ECOG-4201 trial also demonstrated a survival benefit with single-agent gemcitabine and RT.22 Similarly, two recently published studies, LAP07 and the French FFCD-SFRO, both failed to demonstrate a survival benefit with RT, with single-agent gemcitabine and concurrent fluorouracil-based chemotherapy with conventionally fractionated radiation.7,23 Since the inception of these studies, landmark trials have demonstrated that FOLFIRINOX and gemc-itabine plus nab-paclitaxel are superior to single-agent chemotherapy,8,9 and these combination regimens have been rapidly adopted. These two studies also may have lacked the statistical power to detect a survival difference, as the subset of patients who received single-agent chemotherapy in our study also appeared to benefit from addition of RT. In our series, over 4000 patients received RT with single-agent chemotherapy as compared with 59 and 109 patients in the French FFCD-SFRO and LAP07 studies, respectively.7,23 Additionally, recent retrospective evidence also suggests that SBRT may provide superior overall survival compared with conventionally fractionated radiation.14 Thus, application of the randomized data to current clinical practice is limited, and the true benefit of combined modality therapy in the setting of optimized chemotherapy and radiotherapy may be underestimated.

The LAP07 study demonstrated that progression-free survival was prolonged with CRT without a significant impact on overall survival.7 Progression was more often distant (60% of recurrences) in the CRT arm and more often locoregional (46% of recurrences) in the CT arm. It is reasonable to hypothesize that improved control of sub-clinical systemic disease with multiagent CT would further improve progression-free survival in the chemoradiation arm and possibly translate to an overall survival advantage. Median overall survival in LAP07 was 12.8 months, which was similar to the CRT group (12.3 months) but better than the CT group (9.8 months) in the current study. In the current study, Charlson–Deyo score was 0 in 70% of patients compared with WHO PS 0–1 in 90% of patients in LAP07. Furthermore, the exclusion of any surgical resection in this study likely excludes a small proportion of patients who initially presented with advanced disease but were able to undergo resection after induction therapy; median survival of patients undergoing surgery (n = 18) in LAP07 was 30.9 months.

This study has limitations inherent to retrospective studies. The most significant is potential selection bias towards healthier patients to receive CRT. We attempted to minimize the possibility of this type of bias through propensity-score matching of patients, specifically in terms of their age, comorbidity score, and tumor characteristics. While we recognize that propensity matching cannot perfectly nullify selection bias, we have taken maximal efforts to minimize its effects. Additional confounding factors may also favor the radiation cohort, due to variables that the NCDB does not provide, such as tumor-specific markers and the tumor’s spatial relationship to patient anatomy. Thus, we believe that such selection bias cannot truly be eliminated short of prospective randomized trials. Also possible is guarantee-time bias, where the time between diagnosis and RT is awarded to the CRT cohort without a true lengthening of survival time following treatment. We employed a conditional landmark analysis to minimize possible guarantee-time bias for the cohort of patients receiving RT. Our results indicated that, despite accounting for these two types of bias, the CRT cohort demonstrated significantly longer survival than the patients who received CT alone.

Additional limitations to this study are inherent to all studies using the NCDB. Most prominently, the NCDB does not contain details regarding the specific CT agent used, dose, or number of cycles administered. The heterogeneity of chemotherapy and radiation therapy used should be considered. In an effort to account for varying CT used, patients were propensity matched for their year of treatment, which we used as a surrogate for the dominant chemotherapy used at that time. Additionally, data regarding disease progression, recurrence patterns, toxicity, and cause of death are not captured by the NCDB, which represents a further limitation.

Despite these limitations, this study represents the real practice-based outcomes of the majority of patients treated in the USA outside of the clinical trial setting. To our knowledge, our series is the largest of its kind and is currently the best data outside of large, multicenter randomized trials, which are unlikely to be conducted to answer this particular question. In the absence of such data, our study suggests that patients should be evaluated in a multidisciplinary setting and that radiation therapy, particularly SBRT, be discussed and strongly considered.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-6322-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

DISCLOSURE None.

References

- 1.Surveillance. Epidemiology, and End Results Program. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: pancreas cancer. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html.

- 2.Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al. Pancreaticoduo-denectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221(6):721–731. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00011. (discussion 731–723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2004;363(9414):1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15841-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kooby DA, Gillespie TW, Liu Y, et al. Impact of adjuvant radiotherapy on survival after pancreatic cancer resection: an appraisal of data from the national cancer data base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3634–3642. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3047-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Comparative therapeutic trial of radiation with or without chemotherapy in pancreatic carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5(9):1643–1647. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(79)90789-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Treatment of locally unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas: comparison of combined-modality therapy (chemotherapy plus radiotherapy) to chemotherapy alone. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80(10):751–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammel P, Huguet F, van Laethem JL, et al. Effect of chemoradiotherapy vs chemotherapy on survival in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer controlled after 4 months of gemcitabine with or without erlotinib: the LAP07 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1844–1853. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaib WL, Hawk N, Cassidy RJ, et al. A phase 1 study of stereotactic body radiation therapy dose escalation for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer after modified FOLFIRINOX ( NCT01446458) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(2):296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahadevan A, Jain S, Goldstein M, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy and gemcitabine for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78(3):735–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herman JM, Chang DT, Goodman KA, et al. Phase 2 multi-institutional trial evaluating gemcitabine and stereotactic body radiotherapy for patients with locally advanced unre-sectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2015;121(7):1128–137. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang DT, Schellenberg D, Shen J, et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy for unresectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer. 2009;115(3):665–672. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong J, Patel K, Switchenko J, et al. Outcomes for patients with locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with stereotactic body radiation therapy versus conventionally fractionated radiation. Cancer. 2017;123(18):3486–3493. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menck HR, Cunningham MP, Jessup JM, et al. The growth and maturation of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer. 1997;80(12):2296–2304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971215)80:12<2296::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Partridge EE. The National Cancer Data Base: ten years of growth and commitment. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48(3):131–133. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.48.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4(6):567–579. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nickleach DLY, Shrewsberry A, Ogan K, Kim S, Wang SAS® Macros to Conduct Common Biostatistical Analyses and Generate Reports. SESUG 2013: The Proceeding of the SouthEast SAS User Group. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC, Grootendorst P, Anderson GM. A comparison of the ability of different propensity score models to balance measured variables between treated and untreated subjects: a Monte Carlo study. Stat Med. 2007;26(4):734–753. doi: 10.1002/sim.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin DY WL. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc. 1989;84(408):1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giobbie-Hurder A, Gelber RD, Regan MM. Challenges of guarantee-time bias. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2963–2969. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loehrer PJ, Sr, Feng Y, Cardenes H, et al. Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(31):4105–4112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chauffert B, Mornex F, Bonnetain F, et al. Phase III trial comparing intensive induction chemoradiotherapy (60 Gy, infusional 5-FU and intermittent cisplatin) followed by maintenance gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone for locally advanced unre-sectable pancreatic cancer. Definitive results of the 2000-01 FFCD/SFRO study. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(9):1592–1599. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.