Abstract

The nose is the most central and anterior projecting facial feature. Therefore, the presence of a defect is easily noticeable to the untrained eye. Return of the defect to the original form is an achievable end goal of reconstruction, necessitating appropriate reformation of three-dimensional geometry, proper establishment of symmetry, and excellent color and texture match to the adjacent structures. Regarding its physiological importance, disruption of the normal function may cause respiratory obstruction and contribute to patient distress. To achieve successful repair, preoperative preparation must consider the location, the layers involved, and the size of the defect. Prompt and well-organized repair minimizes the occurrence of progressive necrosis and severe late-stage deformity. Here the authors provide a framework to approach various nasal defects and provide a review of the novel ideologies and techniques. The workhorse of nasal repair, the forehead flap, is discussed independently due to the breadth of innovation.

Keywords: nasal reconstruction, multilayer defect, mucosa, algorithm, forehead flap

Mohs micrographical surgery is a precise method to circumferentially excise tumors, producing unique defects that may cross multiple aesthetic units. 1 van Leeuwen et al 2 found that among patients undergoing facial reconstruction following Mohs surgery, 53% had a defect in the nasal subunit. The high incidence of defects in the nasal subunit accentuates the principle that the nose is one of the most sun-exposed facial structures, marking an increased risk for melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers. 1 While adequately resecting tumors, substantial nasal defects can remain, requiring extensive, intricate reconstructive surgery to restore form, aesthetic appearance, and nasal function. In fact, reconstruction of the nasal subunit tends to require the most additional reconstructive operations because of the need for multistaged procedures and also has the most complications because of the inherent complexity of nasal defects. 2

Nasal defects can occur following tumor resection, trauma, and burns. Since the nose is the most central and prominent aesthetic component of the face, even the smallest of defects can produce aesthetic and psychosocial concerns for patients. Understandably, large defects can encase multiple nasal subunits and adjacent facial structures. These defects are three-dimensional in nature and can disrupt the cutaneous skin, cartilage and bone, or the internal mucosal lining, in varying degrees. Thus, an understanding of the reconstructive goals of the patient as well as the extent of the injury is vital to tailor the procedure to the needs of the patient. Here we present a framework for nasal reconstruction and discuss modern techniques geared toward restoring nasal structure and function as well as optimizing aesthetic appearance.

Reconstruction Principles

Subunit Principle

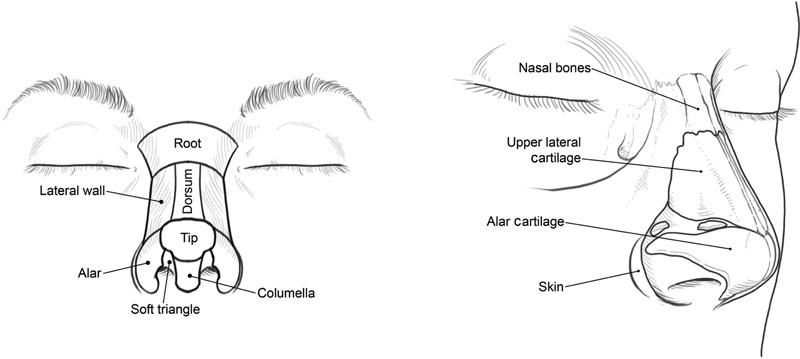

The nose comprises 10 aesthetic subunits: the root, dorsum, bilateral sidewalls, bilateral alar lobules, bilateral soft triangles, nasal tip, and columella ( Fig. 1 ). 3 Each subunit has unique topographical characteristics that guide reconstruction. The subunit principle dictates that when a defect comprises more than one half of an individual subunit, the defect margins should be extended to the boundaries of the subunit and then the entire subunit should be uniformly reconstructed. 3 Application of this principle minimizes conspicuous scar formation by maintaining uniform tissue within a subunit and concealing scars along the borders of the defective subunit. Convex nasal structures, such as the ala, tip, and bilateral soft triangles, are ideal for applying the subunit principle because of the sharp boundaries that provide scar camouflage. The foreseeable scar contracture that occurs from the cutaneous flap overlying the subunit wound also helps in reestablishing the desired convexity of the nasal subunit. 4 5

Fig. 1.

The nose is divided into 10 aesthetic subunits (left) and consists of three anatomical layers: skin, cartilage and bone, and a thin inner mucosal lining (right). (Reproduced with permission from Texas Children's Hospital.)

Reconstruction Algorithms

There are multiple methods available to successfully reconstruct a given defect; the ultimate goal of reconstruction is to restore structural support and functionality of the nose as well as to optimize aesthetic appearance. Development of algorithms to narrow the choices permits an easier, less timely selection of treatment. Primary factors to consider when approaching nasal defects include the location, size, and depth of the injury. In terms of location and size, the subunit(s) involved and extent into adjacent facial aesthetic zones should be determined. Wound depth should also be evaluated for the involvement of underlying cartilage, bone, or internal mucosal lining. Furthermore, individual factors such as medical comorbidities and vascular disease, psychological burden of nasal deformity, and personal reconstructive goals are important to consider when choosing a productive reconstructive method.

Konofaos et al 6 describes an algorithm in which as much as 91% of defects can be reconstructed with one of five techniques: bilobed flap, forehead flap, full-thickness skin graft (FTSG), nasolabial flap, or dorsal glabellar flap ( Table 1 ). 6 The algorithm emphasizes that certain nasal defect locations are heavily associated with a specific reconstructive method. The indications for each reconstructive method based on size and depth of injury are discussed in the subsequent sections.

Table 1. Algorithm of nasal reconstruction based on location of defect.

| Location | Reconstruction method |

|---|---|

| Ala | Nasolabial flap (93.2%) Full-thickness skin graft (6.8%) |

| Dorsum/sidewalls | Local flaps (bilobed and dorsal glabellar) (67.9%) Advancement flap (11.5%) |

| Tip | Forehead flap (92.5%) |

| Internal lining | Folded forehead flap (48.9%) Mucosal flaps (34.7%) Full-thickness skin graft (8.51%) Nasolabial (6.38%) |

Construction Guided by Layer Involved

The nose contains three major anatomical layers: a protective cutaneous layer, a structural cartilage and bone layer, and an internal thin mucosal layer ( Fig. 1 ). Depending on the cause and magnitude of injury, damage may involve more than one layer, and repair must appropriately address each one specifically.

Mucosal Layer Involvement

Initial injury to the nasal mucosa, because of trauma, immune-mediated disease, cocaine-associated vasoconstriction, or infection, causes scar formation and structural loss. 7 8 Persistent, untreated injury can evolve into necrosis, spreading throughout the nasal vault and floor. This substantial necrosis threatens centripetal scar contraction and may result in regression of the upper lip, retraction of the nostril margins and columella, and shortening of the nose. 7 Therefore, primary-staged repair of damaged mucosal lining is crucial to prevent injury progression, necrosis, and late deformities.

Depending on the degree of mucosal injury and concomitant surgical operations, the major reconstructive techniques available are the intranasal lining, hinge-over, regional, and distal flaps. Although the aforementioned flaps are useful to repair a wide range of mucosal defects, the double forehead flap, turn-in skin flap, and facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap have gained recent applicability.

The intranasal lining, hinge-over, and turn-in skin flaps are indicated for small mucosal defects, less than 1.5 cm in diameter. Defects with surrounding undisturbed mucosa are reparable with local intranasal lining flaps, using special care to not excessively damage normal mucosa. The intranasal flap is quite thin and does not have the capability to restore considerable structural defects because of its inability to support large cartilage structures. 7 9 10

Full-thickness defects located in the distal portions of the nose are reparable with hinge-over flaps. In this method, a fasciocutaneous flap, occasionally with inclusion of underlying adipose tissue or muscle, is designed adjacent to the defect. The local flap is incised, the overlying skin is removed, and the remaining tissue is flipped over on its pedicle to fill the depth of the defect. Then, the removed skin or a separate skin graft is placed over the flap to provide cutaneous coverage. Alternatively, a delay period may be used to permit secondary healing over the defective margin, which provides a prelaminated tissue source. After healing, the newly formed tissue is inferiorly excised and folded over itself to recreate the mucosa. Reconstruction of the mucosa with thin and strong nasal skin prevents stenosis of the airway and supports cartilage grafts, respectively.

As described by Yazar et al, 8 the turn-in skin flap reconstructs the mucosal lining using cutaneous tissue from the margin of the defect. The cutaneous tissue is circumferentially incised, elevated, turned over, and sutured at the midpoint. In situations that meet the criteria of reconstruction by the subunit principle and require excision of the surrounding cutaneous tissue in the subunit, the technique repurposes the normally discarded tissue for use in the turn-in skin flap to avoid additional donor-site morbidity.

Regional flaps are indicated for large mucosal defects (greater than 1.5 cm in diameter) and include the forehead, melolabial, and nasolabial flaps. Due to the ability to manipulate the extension length, regional flaps may also be used to repair small mucosal defects. The folded forehead flap consists of a distal extension that folds over itself to reconstruct the mucosal lining. 11 12 The folded lining provides a scaffold for implementation of a cartilage graft to reestablish structural support. Additional vertical extension of a forehead flap presents a challenge in individuals with short foreheads. Conversely, the nasolabial and melolabial mucosal flaps can directly position the distal extensions of the cutaneous flaps over the mucosal defect. Due to the thick nature of cheek tissue, which has the propensity to bulge externally and obstruct the airway, the nasolabial and melolabial flaps are infrequently used. 9

Distal flaps and free flaps are called upon for substantial, complex mucosal defects that involve both the nasal floor and vault and are not repairable by other methods. Generally, the radial or ulnar forearm flaps are used due to the availability and the relative similar composition to that of the mucosa. However, the distal tissue is generally thicker than local tissue and may obstruct the airway. Large free-flap transfer results in substantial donor-site morbidity and requires independent vascularization of the flap at the defect site. Therefore, patients who have systemic vascular comorbidities and are active smokers are not ideal candidates for repair. 4 7 9 10

The double forehead flap achieves full-length mucosal and cutaneous reconstruction. Zelken et al 13 advocates for the use of the double forehead flap in patients with large full-thickness defects who are not candidates for reconstruction with regional or distal flaps. The authors reserve the first forehead flap for mucosal repair and the second flap for cutaneous repair. Due to the large surface area of the donor site and the use of both paramedian forehead flaps, the technique has a prolonged donor-site healing time.

Rahpeyma and Khajehahmadi 14 describe a new role for the superiorly based FAMM flap for an individual with a large mucosal defect, a large septal perforation, and a short forehead. The FAMM flap reconstructs the mucosal defect with transposition of the buccal mucosa and the buccinator muscle to the nasal region through an incision on the floor of the nose. To reduce tension on the flap, an island variant flap can be used with the facial artery included in the thickness of the flap. As oral mucosa is transposed to the nasal lining, the flap produces saliva and lacks goblet cells. Saliva production is not considered negative because of the restoration of a moist nasal environment, which minimizes dryness and crust formation. Conversely, the lack of goblet cells is considered negative, as it decreases overall mucous output.

Structural Layer Involvement

Through an intricate network of cartilage and bone, the nose maintains structural support against gravity and impending external forces. The preferred cartilage donor site is the ipsilateral conchal bowl; additionally, the costochondral cartilage is reserved for circumstances that require larger amounts of cartilage. 11 Mild-to-moderate deformities are amendable to repair by onlay cartilage grafts, 7 which are used routinely for the columella, tip, and ala. 13 15 Interestingly, the normal ala does not have any cartilage, but repair often requires cartilage grafting to restore convex shape and to provide structural support that maintains airway patency. 13 Major deformities that eradicate dorsal and septal support require open cantilever dorsal graft and tip support. 7 The technique uses a two-stage approach that recreates the dorsum with a costal cartilage brace and the tip with a columellar cartilage brace.

Cutaneous Layer Involvement

Perceptible to the external environment, cutaneous layer defects can produce unacceptable aesthetic outcomes and, moreover, serve as a conduit for infection. To simplify the indications for flap selection, small-sized nasal defects are discussed separately from intermediate- and large-sized nasal defects.

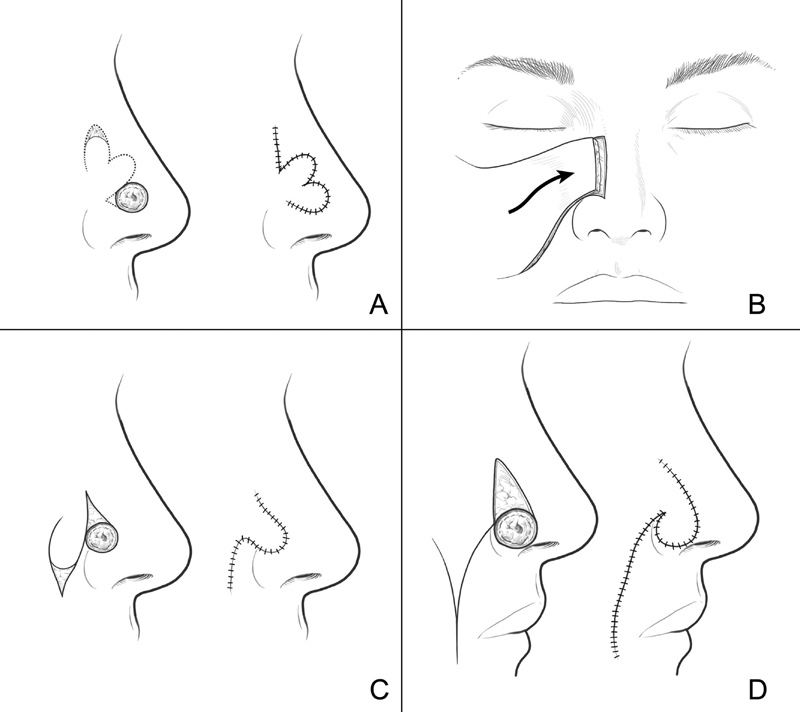

Defects less than 1.5 cm in diameter are considered small-sized. The smallest defects, generally less than 0.05 cm, are amendable to primary repair, which is a simple and minimally time-consuming procedure. 1 However, caution must be undertaken during primary closure to prevent inadvertent narrowing or obstruction of the nasal airway. In an analysis of 788 nasal reconstructions, Moolenburg et al 16 found that for defects smaller than 1.5 cm, where primary closure was not possible, the most applicable reconstructive techniques were skin grafts and local tissue rearrangement flaps. Skin grafts are used in every subunit, whereas local tissue rearrangement flaps differ based on location. The melolabial and nasolabial flaps are considered the most useful options for the lateral sidewall, ala, and vestibule; the cheek advancement flap is used for the lateral sidewall; the V-Y advancement flap is typically performed for the nasal dorsum and columella; the dorsal nasal flap helps repair the nasal dorsum and tip; and the bilobed flap effectively reconstructs the tip and ala ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). 16 For defects located on the cranial aspect of the nasal dorsum, the glabellar flap is most commonly used. 1

Fig. 2.

Local flaps are effectively used to reconstruct a variety of nasal defects. Some options include bilobed ( A ), cheek advancement ( B ), nasolabial ( C ), and melolabial ( D ) flaps. (Reproduced with permission from Texas Children's Hospital.)

Fig. 3.

Bilobed flap used to reconstruct nasal tip defect.

Historically, defects larger than 1.5 cm in diameter were always considered large-sized defects. Advancement of a new category, intermediate-sized defects, between 1.5 cm and 2.5 cm, provides an additional category to allow specialization of reconstructive techniques. Yong et al 17 analyzed 315 patients with intermediate-sized nasal defects and found that the most common methods of repair were local flaps (30.8%) and forehead flaps (29.8%). For these nasal defects, the surgeon can pull a variety of techniques from his/her armamentarium to specialize and individualize the reconstructive approach that optimizes aesthetic appearance and best meets the patient's functional needs.

Large defects, categorized as either greater than 1.5 or 2.5 cm, require regional flaps or FTSGs because of the appreciable loss of surface area. Large cutaneous defects often also involve the underlying structural network and mucosal layer; therefore, structural and mucosal repair occurs concomitantly. The major reconstructive options available are the forehead flap, bilateral cheek advancement flap, melolabial flap, nasolabial flap, and FTSG. The indications of each reconstructive method are summarized in Table 2 .

Table 2. Indications and drawbacks for the forehead flap, 5 20 bilateral cheek advancement flap, 4 full-thickness skin graft, 1 melolabial flap, 4 10 and nasolabial flap 5 for cutaneous repair .

| Reconstructive method | Indications | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|

| Forehead flap | Multiple subunit defects that include the ala, tip, columella, and dorsum Folded forehead flap permits reconstruction of multilayered defects including the mucosal lining Young patients with minimal cheek laxity and absence of prominent nasofascial and mesolabial groove |

Multistaged operations spanning several weeks Conspicuous forehead pedicle, with potential psychological and functional burden |

| Melolabial flap | Defects localized to the ala and columella | Multistaged operations with a cheek pedicle visible between procedures Medial cheek and melolabial fold asymmetry Contraindicated in young patients with an indistinct melolabial groove |

| Nasolabial flap | Defects localized to the superficial ala Hairless |

Multistaged operations with a cheek pedicle visible between procedures Shorter flap because of a less than 90-degree arc of rotation Contraindicated in young patients with an indistinct nasolabial fold |

| Bilateral cheek advancement flap | Defects localized to the lateral sidewall and dorsal subunits Patients with medial cheek laxity |

Additional operation required to recreate the nasofascial groove because of blunting |

| Full-thickness skin graft | Defects localized to the lateral sidewall and dorsal subunits in patients who do not wish to or cannot endure multiple operations One-stage operation |

Color mismatch Potential graft loss |

Referred to as the workhorse of nasal repair, the paramedian forehead flap is used extensively for multi-subunit defects of the ala, tip, columella, and dorsum. 5 As mentioned previously, the design of a forehead flap with a foldable distal extension allows reconstruction of the mucosal lining, permitting reconstruction of multilayered defects. The different types and technical advancements of the forehead flap are reserved for the subsequent section. 10

Patients who have a defect involving the distal one-third of the nose and prefer a pedicle attached to the cheek, as opposed to draped from the forehead, are candidates for a unilateral or bilateral melolabial flap ( Fig. 4 ). 4 Multistaged operations are necessary to maintain adequate flap vascularity. In all cases, there is a risk of medial cheek and melolabial fold asymmetry. Thus, a nasolabial or nasofascial flap can be implanted for alar defects in patients who prefer a pedicle attached to the cheek and do not wish to risk melolabial or cheek asymmetry ( Fig. 5 ). 5 Designed as an inferiorly based interpolated flap, the nasofascial flap spares the medial cheek fat pad and requires a rotation arc less than 90 degrees, minimizing medial cheek asymmetry. 5

Fig. 4.

Staged reconstruction of alar defect with a melolabial flap.

Fig. 5.

Nasolabial flap implemented to reconstruct large alar and lateral sidewall defect.

Individuals with a defect located on the lateral sidewall or dorsal subunit, with appreciable bilateral cheek laxity, are excellent candidates for bilateral cheek advancement flaps. 4 Medial cheek flaps are elevated in the subcutaneous plane and extended to meet in the midline to construct a durable vascular supply for the nose. Additional procedures are often required to restore the nasofascial groove and normal external contour of the nose. In fact, an FTSG is an alternative option for patients with lateral sidewall or dorsal subunit defects who do not wish to or cannot endure multiple operations. 4 Depending on the color and texture match, the main donor sites include the helical root, helical rim, preauricular area, and lateral forehead. 4

Forehead Flap

Relevant Anatomy

Highly vascularized, the forehead contains several major arteries with anastomosing connections. 18 The supratrochlear artery (STA), a major terminal branch of the ophthalmic artery, arises from the superomedial orbit and penetrates the corrugator complex, before traveling subcutaneously and giving off superficial cutaneous branches, deep muscular branches, and anastomosing collaterals. Doppler studies have shown that the STA is located an average of 10.9 mm from the midline. 19 The forehead contains tissue with comparable texture and color to that of the nose. 20 Therefore, the forehead flap is used extensively in nasal repair for the reconstruction of the distal subunits of the ala, tip, columella, and dorsum. 21 The forehead flap is also used in the reconstruction of full-thickness defects, as folding the distal portion of the flap recreates the mucosal lining and provides a site for the placement of cartilage grafts. 22 Following the operation, forehead closure does not provide a significant aesthetic concern, as primary closure, fixed tension bridging sutures, and secondary healing all provide an appropriate outcome. 21 23

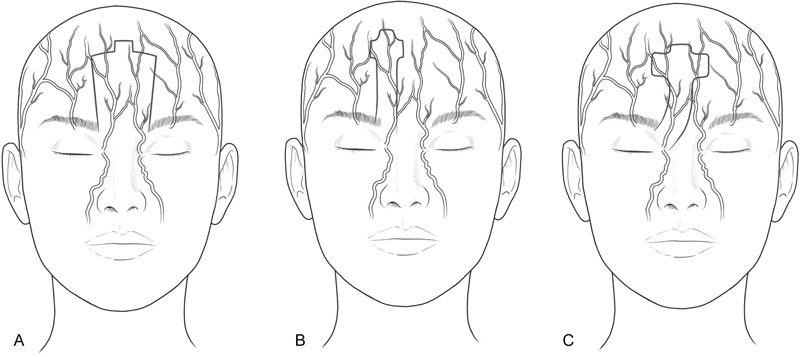

Flap Location

Traditionally, Doppler ultrasound is used to base the paramedian forehead flap directly over the STA to create an axial flap with a dependable vascular supply. 11 An ipsilateral flap design is preferred to limit required flap length, maintain the presence of the axial blood supply, and preserve the contralateral forehead. 11 Moreover, the width of the flap is minimized between 12 and 14 mm to limit flap congestion. 11 Alternate techniques to the paramedian forehead flap include the paramidline and medial forehead flap ( Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Forehead flaps are popularly used in nasal reconstruction and are designed as a medial ( A ), paramedian ( B ), or paramidline ( C ) flap depending on the blood supply. (Reproduced with permission from Texas Children's Hospital.)

The landmark-based paramidline forehead flap extends from the midline to 1.2 cm lateral to the midline. Although the flap does not contain a designated axial artery, the flap is grounded on the rich, complex vascular plexus of the glabella. Stigall et al 18 compared the Doppler-guided paramedian forehead flap with the landmark-based paramidline forehead flap and determined that there is no significant difference in flap survival or complication rate. Interestingly, the paramidline flap had a higher incidence of arteritis within the vascular pedicle. 18 It is, nevertheless, best implemented in individuals with short foreheads, as the midline location of the flap minimizes brow distortion and permits a more caudal extension for soft tissue nasal coverage.

As described by Oo and Park, 24 the medial forehead flap is centered on the midline, with incision lines located 5 to 6 mm bilaterally. Like the paramidline flap, the medial forehead flap contains the vascular plexus of the glabella and permits a caudal application. The central location of the flap minimizes brow distortion, compared with the paramedian and paramidline flap, and reduces the necessary twist of the pedicle for unilateral defects. However, for bilateral defects, necessary rotation may exceed 180 degrees, possibly increasing the risk of strangulation and ischemia. Furthermore, if a patient with a previous medial forehead flap needed additional soft tissue coverage, scar tissue from the initial donor site may limit the availability of another medial forehead flap. Fortunately, a paramedian forehead flap is practical due to the undisturbed tissue lateral to the position of the previous medial forehead flap.

Several options exist for circumstances that require additional flap length. First, modification of the forehead flap can create extra length by planning an additional horizontal component toward the contralateral side, such as in the Parkland flap. 11 Although this flap has a decreased pedicle rotation and avoids the hairline, it also disrupts the contralateral forehead and incorporates a random vascular supply to the horizontal component of the flap. Second, expansion technology permits an increase in the surface area of the donor tissue up to 1.5 to 2 times the size of the nonexpanded tissue. 25 Expansion of scarred forehead skin, because of previous forehead flaps or external causes, can establish structurally and aesthetically appropriate tissue for use in additional forehead flaps. 10 Due to the progressive, interval nature of expansion, the process can range from 10 to 18 weeks to obtain appropriate tissue length, requiring the patient to attend multiple inpatient expansion sessions. 25 The high compliance demand may produce a physical and psychological burden on the patient, but a subset of patients with extensive defects are willing to make the sacrifice.

Stages of Operation

Conventionally, application of the forehead flap occurs in two separate surgical operations. The delay provides time for revascularization of the translocated flap to areas adjacent to the defect. 20 Sanniec et al 11 provides an excellent description of the surgical procedure for the two-staged paramedian forehead flap. In the first stage, the flap is elevated, rotated to the appropriate conformation, and sutured to the defect location. 11 The distal portion of the flap is not reelevated in subsequent stages; therefore, aggressive thinning of the distal portion usually occurs during the first stage. In the second stage, the flap is divided from the forehead, thinned at the proximal portion, and sutured into its final location. Between the first and second operation, the flap maintains a connection between the patient's forehead and nose.

The presence of a forehead pedicle is psychologically debilitating and may cause a patient to take leave from work. Hair from the distal portion of the forehead flap along the anterior hairline may be transferred down to the nose, resulting in thick hair formation highly visible on the nasal tip and ala. More importantly, the bulky and overt forehead pedicle prior to division is aesthetically concerning. The time interval between the two stages differs in the literature, varying from 3 weeks, 20 4 weeks, 11 to 4 to 6 weeks. 26 Earlier flap division results in increased psychosocial well-being for the patient but jeopardies vascularity of the flap. Although additional procedural costs are required, intraoperative laser fluorescence angiography (ILFA) can assess the vascularity of the flap to determine if flap division is safe to perform at an earlier time. 27 Calloway et al 27 determined that division at the 2-week mark supported by positive ILFA results, in comparison to division at 3 weeks without an ILFA, can produce an average cost savings of $177 per patient. Although limitations exist in the calculations, the study emphasizes that the use of technology to decrease the time to pedicle division may promote emotional well-being and also balance and even undershoot the cost-associated productivity lost.

Alternatively, the three-stage forehead flap incorporates an extra procedure between flap insertion and flap division. This additional stage allows for increased revascularization time and more aggressive debulking and sculpting of the flap. The three-stage forehead flap is preferred for more complex operations, including patients with preexisting systemic risk factors and patients with medium-to-large defects who require mucosal lining and cartilage framework repair. 89 It has shown that there is no significant difference in flap viability or postoperative satisfaction in flap appearance between the two-stage and three-stage forehead flaps. 28

On the alternate end of the spectrum, a one-stage forehead flap eliminates the necessity for multiple operations and avoids the aesthetic and psychosocial burden of a bulky, temporary forehead pedicle. Innocenti and Innocenti 9 describe a one-stage forehead flap that uses a subcutaneous tunnel to pass the STA and transpose tissue from the forehead to the nose, all while maintaining the vascular connection to the flap. Although surgically complicated, the technique alleviates patients' distress and provides satisfactory results. 9 The technique is reserved for partial nasal reconstructions where there is evident Doppler identification of the STA for greater than several centimeters.

Nuances and Complications

The patient requires wound dressings and good personal hygiene to minimize postoperative bleeding, prevent infections, and stabilize the flap. 23 The flap and wound dressing interfere with the ability of the patient to wear glasses. 26 Innovative solutions to circumvent this issue include attachment of the spectacles to the brim of a baseball cap 26 or exchange of the glasses' nose support with a metal saddle bridge that can disconnect and reconnect to fit beneath the forehead flap. 29

Careful flap design and inset is paramount to avoid inadvertent narrowing of the nasal passageway, which would result in obstruction and difficulty in nasal breathing. A hematoma or seroma may develop following repair and must be immediately treated to preserve flap viability and nasal structure. In addition, the overall infection rate of facial reconstruction is low at approximately 0.7%; however, cutaneous nasal repair makes up approximately 63% of these uncommon instances of infection. 30 Thus, perioperative antibiotics such as azithromycin should be highly considered in nasal reconstruction cases, especially given the proximity of the flap to colonized areas of the nasal mucosal lining, nasopharynx, and oropharynx. 1

While topical nitroglycerin is applied to reduce flap necrosis in many cases, such as free-flap-based reconstruction, little evidence has proven this method to be effective. 1 Flap necrosis and distal skin tip necrosis may occur in nasal reconstruction in which the flap is overly thinned, pedicle base is made too narrow, or too sharp of an arc of rotation is created when folding the forehead flap down over the defect. Once the flap has died, it can be difficult to find another local flap for adequate soft tissue coverage, especially another forehead flap when both sides have already been exhausted in initial reconstructive surgeries. Thus, it is imperative for surgeons to balance flap mechanics and aesthetics when strategizing the reconstructive approach to preserve flap viability and adequately restore the nasal structure, all while striving for the best aesthetically appearing end result as much as possible.

Conclusion

Due to its central and anterior projecting location in a sun-exposed area, the nose is prone to skin cancers, trauma, and infection, which may all lead to highly visible and aesthetically concerning nasal defects. These nasal wounds can also be functionally impairing when the nasal airway is not appropriately addressed. Therefore, reconstruction must match the texture and color of the cutaneous layer with adjacent structures, reengineer the three-dimensional structure, and reform the internal mucosal layer. Large, multilayer defects require creativity and assistance from regional and distal tissue sources. Guiding repair to the aspirations of the patient is paramount and determines the overall success of reconstruction.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Conflict of Interest None.

Products/Devices/Drugs

None.

References

- 1.Rogers-Vizena C R, Lalonde D H, Menick F J, Bentz M L. Surgical treatment and reconstruction of nonmelanoma facial skin cancers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(05):895e–908e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Leeuwen A C, The A, Moolenburgh S E, de Haas E R, Mureau M A. A retrospective review of reconstructive options and outcomes of the 202 cases large facial Mohs micrographic surgical defects based on the aesthetic unit involved. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19(06):580–587. doi: 10.1177/1203475415586665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burget G C, Menick F J. The subunit principle in nasal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(02):239–247. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198508000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox A, Fort M. Nasal reconstruction involving multiple subunit defects. Facial Plast Surg. 2017;33(01):58–66. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1597898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menick F J. Forehead flap: master techniques in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30(02):131–144. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1371904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konofaos P, Alvarez S, McKinnie J E, Wallace R D. Nasal reconstruction: a simplified approach based on 419 operated cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39(01):91–99. doi: 10.1007/s00266-014-0417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menick F J, Salibian A. Primary intranasal lining injury cause, deformities, and treatment plan. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(05):1045–1056. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yazar M, Yazar S K, Kozanoğlu E, Diyarbakırlıoğlu M, Eren Hİ. Use of turn-in skin flaps for nasal lining reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(10):1208–1212. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Innocenti A, Innocenti M. An alternative single-stage application of the paramedian forehead flap in reconstruction of the face. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016;44(10):1678–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rezaeian F, Corsten M, Haack S, Gubisch W M, Fischer H. Nasal reconstruction: extending the limits. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(07):e804. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanniec K, Malafa M, Thornton J F. Simplifying the forehead flap for nasal reconstruction: a review of 420 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(02):371–380. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menick F J. A new modified method for nasal lining: the Menick technique for folded lining. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94(06):509–514. doi: 10.1002/jso.20488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zelken J A, Chang C S, Reddy S K, Hsiao Y C. Double forehead flap reconstruction of composite nasal defects. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69(09):1280–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahpeyma A, Khajehahmadi S. Facial artery musculomucosal (FAMM) flap for nasal lining in reconstruction of large full thickness lateral nasal defects. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015;4(04):351–354. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Pochat V D, Alonso N, Ribeiro E B et al. Nasal reconstruction with the paramedian forehead flap using the aesthetic subunits principle. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(06):2070–2073. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moolenburgh S E, McLennan L, Levendag P C et al. Nasal reconstruction after malignant tumor resection: an algorithm for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(01):97–105. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181da872e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yong J S, Christophel J J, Park S S. Repair of intermediate-size nasal defects: a working algorithm. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(11):1027–1033. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stigall L E, Bramlette T B, Zitelli J A, Brodland D G. The paramidline forehead flap: a clinical and microanatomic study. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42(06):764–771. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vural E, Batay F, Key J M. Glabellar frown lines as a reliable landmark for the supratrochlear artery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(05):543–546. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menick F J.A 10-year experience in nasal reconstruction with the three-stage forehead flap Plast Reconstr Surg 2002109061839–1855., discussion 1856–1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer H. Nasal reconstruction with the paramedian forehead flap--details for success. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30(03):318–331. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1376918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jellinek N J, Nguyen T H, Albertini J G. Paramedian forehead flap: advances, procedural nuances, and variations in technique. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(09) 09:S30–S42. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brodland D G.Paramedian forehead flap reconstruction for nasal defects Dermatol Surg 200531(8 Pt 2):1046–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oo K K, Park S S. The midline forehead flap in nasal reconstruction. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;26(03):407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Song W, Hou D, Wang J. Expanded forehead flaps for reconstruction of different faciocervical units: selection of flap types based on 143 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(05):1461–1471. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison J L, Mahmood S, Scott J S. Modification to facilitate the wearing of spectacles by patient after reconstruction with a paramedian forehead pedicled flap. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54(09):1036–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calloway H E, Moubayed S P, Most S P. Cost effectiveness of early division of the forehead flap pedicle. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(05):418–420. doi: 10.1001/jamafacial.2017.0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos Stahl A, Gubisch W, Fischer H, Haack S, Meisner C, Stahl S. A cohort study of paramedian forehead flap in 2 stages (87 flaps) and 3 stages (100 flaps) Ann Plast Surg. 2015;75(06):615–619. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu L T, Kelpin J P, Eichhorn M G, Komorowska-Timek E. Spectacles under pedicles: eyewear modification with the paramedian forehead flap. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(08):e1003. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maragh S L, Brown M D. Prospective evaluation of surgical site infection rate among patients with Mohs micrographic surgery without the use of prophylactic antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(02):275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]