Abstract

The umbilical cord is a direct conduit to the fetus, hence transporters could have roles in partitioning substances between the maternal-placental-fetal units. Here we determined the expression and localization of the ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) transporters BCRP (ABCG2), P-gp (ABCB1) and MRP1 (ABCC1) in human umbilical cords.

The mRNA for BCRP and MRP1 was detected in 25/25 samples, but P-gp was detected in only 5/25. ABC transporter mRNA expression relative to 18S was 25.6±0.3, 26.5±0.6 and 22.2±0.2 cycles for BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp respectively.

Using a subset of 10 umbilical cords, BCRP protein was present in all samples (immunoblot) with positive correlation between mRNA and proteins (P=0.07, r=0.62) and between immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (P=0.03, r=0.67). P-gp protein was observed in 4/10 samples by both immunoblot and IHC, with no correlation between mRNA and protein (P=0.45, r=0.55) or immunoblotting and IHC (P=0.2, r=0.72), likely due to small sample size. MRP1 protein was not observed.

Localization of BCRP and P-gp proteins was to Wharton's jelly with no specific staining in arterial or venous endothelia.

Understanding ABC transporter expression in the umbilical cord may be useful for determining fetal exposures to xenobiotics if functional properties can be defined.

Introduction

In the maternal-placental-fetal unit, the placenta and maternal liver are the primary organs for detoxification and protection of the developing child. Thus, the placenta is generally considered the last defense before a substance passes from the maternal to the fetal circulation, as well as the first opportunity for detoxifying fetal blood returning to the interface (Benirschke and Kaufmann 2000). When substances pass through the placenta, they enter the fetal blood via the umbilical cord. Specifically, the umbilical vein branches away from the placenta with the left branch sending blood into the fetal liver and the right branch sending blood directly to the fetal heart (Benirschke and Kaufmann 2000). After blood has circulated, it once again enters the umbilical cord through the two umbilical arteries, sending wastes, metabolites and parent compounds back to the placenta (Benirschke and Kaufmann 2000).

The structural component of the umbilical cord is called Wharton's jelly, and consists primarily of the mucopolysaccharides hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate, but this tissue also contains fibroblasts, stromal and mesenchymal cells, as well as macrophages (Benirschke and Kaufmann 2000). Therefore, if the umbilical vein can prevent delivery of toxicants after they have transited the placenta, this represents the true final chance to protect the fetus. Similarly, the umbilical arteries present the first chance to remove wastes and toxicants from the fetal unit before they are presented at the placental interface.

A key way in which drugs, chemicals and endogenous compounds are eliminated is active transport across membranes via the ATP-binding Cassette (ABC) proteins (Borst and Elferink 2002). These proteins have promiscuous substrate affinities with the ability to transport a wide range of molecules of diverse sizes and physicochemical properties. This study focuses on the three of the major endo- and xenobiotic ABC transporters BCRP (ABCG2), MRP1 (ABCC1) and P-gp (ABCB1). The mRNA, protein expression and localization of all three of these transporters have previously been reported in placental tissues across gestation (Gil et al., 2005; Kolwankar et al., 2005; Langmann et al., 2003; MacFarland et al., 1994; Nagashige et al., 2003; Pascolo et al., 2003; Sugawara et al., 1988; Yeboah et al., 2006). They have also been well characterized in primary placental cell cultures, the immortalized placental cell lines BeWo, Jar and JEG3 (Evseenko et al., 2006; Ikeda et al., 2012) and in cord blood derived cells, including hematopoietic progenitor, stromal and mesenchymal cells (Ahmed et al., 2008; Alt et al., 2009; Seo et al., 2011; Wagner-Souza et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2007). In these tissues and cells BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp play roles in trans-placental transport of bilirubin and bile acids (Azzaroli et al., 2007; Cui et al., 2009; Pascolo et al., 2001), cytokines and steroid hormones (Evseenko et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008; Yasuda et al., 2006) drugs used in pregnancy (Beghin et al., 2010; Feinshtein et al., 2010; Gedeon et al., 2008; Hemauer et al., 2010; Hodyl et al., 2013; Manceau et al., 2012; Mitra and Audus 2010; Pollex et al., 2010), and common environmental chemicals such as Bisphenol A, the heavy metal cadmium and the pesticide chlorpyrifos (Jin and Audus 2005; Kummu et al., 2012; Ridano et al., 2012).

In addition to physiological and medical roles of transporters in the effects of drugs/chemicals in pregnancy and the neonate, our laboratory (and others) have been determining the utility of umbilical cords to screen for drug use, both licit and illicit (Jones et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2011). One thing that may affect the suitability of umbilical cords for use in quantitative screening is the presence of these ABC transporters. Conceivably, the presence of transport proteins in umbilical tissue may export drugs from the maternal or fetal circulations to each other, or into the amniotic fluid. Additionally, attempts to validate umbilical cords as screening tools for drug and chemical use by the mother and for fetal exposure, should include consideration of transport dynamics when reporting absolute levels of compounds as reflective of either maternal or fetal exposure. The aim of this study was to determine whether the three major ABC efflux transporters BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp are expressed (mRNA and protein) in the human umbilical cord and if so, where these proteins are localized in order to gain insight into their potential functions.

Materials and Methods

All chemicals and reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis MO, USA unless otherwise stated.

Tissue Collection and availability

The human umbilical cords used in this project (n = 25) were released from the Hawaii Biorepository. Cords were collected at birth with informed consent from mothers for inclusion of their tissues into the Biorepository, including consent for future investigation. This individual study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Ethics at the University of Hawaii (CHS # 15080) and the Review Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H14-00092). Adult human kidney and liver slides and lysates used as positive controls in this study were acquired from the commercial vendor Cedarlane (Burlington, ON, Canada).

Umbilical cords (10-12 cm, central portions) were collected, snap-frozen and stored at -80 °C in the Biorepository until use. Pieces of umbilical cord (∼2cm) were also collected and placed in paraformaldehyde, blocked in paraffin and stored at ambient temperature in the Biorepository until use. Upon request, individual pieces of umbilical cord tissue (0.2 – 0.5 g) were cut from the end of frozen cords and shipped on dry ice from the University of Hawaii to The University of British Columbia, where they were stored at -80 until use. The corresponding paraffin blocks were microtomed by the Histopathology Core at the John A. Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii to 4-7 μm thickness, then mounted on poly-L-lysine coated slides and shipped at ambient temperature to the University of British Columbia where they were stored in the dark at room temperature (22 °C) until use.

The characteristics of this cohort are as follows: Maternal age: 28.6 ± 5.3 yr (range 20-42); Gestational age: 38.6 ± 2.3 weeks (range 38-40); Maternal Body Mass Index: 30.4 ± 9.7 kg/m2 (range 16.5 – 39.9); birth weight: 3300 ± 281 g (range 1200 – 3983); Neonates were 10 male and 15 female, maternal anemia n = 10/25; maternal smoker n = 6/25; Chorioamnionitis n = 4/25, Premature membrane rupture n = 4. There were no samples with: use of illicit drugs, pre-term labor, Types 1, 2 and gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia or neonatal abnormalities.

Extraction of mRNA and cDNA preparation

Total RNA was extracted from 0.2 – 0.5 g of thawed umbilical cord. Tissue was homogenized with a rotor-stator homogenizer in RLT buffer (Qiagen, Valencia. CA) at 1:3 w:v, followed by RNA isolation using RNeasy Mini kit according to the manufacturer's instruction (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The RNA purity and concentration were determined by Nanodrop (ThermoFisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE), then RNA was aliquoted and stored at -80°C until use when it was thawed and 50 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with an ABI High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, Burlington, ON) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

SYBR Green q-RT-PCR and primer selection

Primer sequences for BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp used for real-time PCR (Table 1, with references) were either as previously described or, in the case of MRP1 designed with PrimerBLAST software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). The primers for MRP1 were designed spanning exon 6 and 7 (forward primer, exon junction 852/853) of the MRP1 gene and checked for specificity using BLAST. The levels of ribosomal rRNA 18S subunit (18S) were used as the semi-quantitation comparator (Table 1). All primers were prepared by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) with standard desalting purification. Real-time PCR was performed using 1 μl of cDNA with forward and reverse primers (BCRP and 18S: 300 nM; MRP1: forward and reverse 500 nM, P-gp: forward 300 nM, reverse 500 nM) on an ABI Step-one-plus real time PCR system (Life Technologies) in triplicate for each cord. Detection was with SYBR Green in a total volume of 20 μl containing 10 μl of PerfeCTa SYBR Green SuperMix for IQ (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD). Cycling conditions were 1 cycle for 30 sec at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of a 5 sec at 95°C, 15 sec 60°C, 10 sec 70°C followed by a melt curve of 15 sec 95°C, 60 sec 60 °C, 15 sec 95 °C. The threshold value detection (CT, cycle number) was set in the exponential phase of amplification. The positive controls were human liver and human kidney mRNA. All products from PCR were electrophoreses on 1.5% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide and UV detection to confirm specificity of the reaction by the presence of only a single band.

Table 1. Primers used in q-RT-PCR.

| Gene | Accession No. | Forward | Reverse | Amplicon length | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCRP | NM_004827 | 5′-TGA CGG TGA GAG AAA ACT TAC-3′ | 5′ -TGC CAC TTT CAG ACC T- 3′ | 122 | (Dutheil 2009) |

| MRP1 | NM_004996.3 | 5′-ATC ACA GGG TTG ATT GTC CG-3′ | 5′-GCG CAT TCC TTC TTC CAG TT-3′ | 128 | novel |

| P-gp | NM_000927 | 5′-CAC CCG ACT TAC AGA TGA TG- 3′ | 5′ -GTT GCC ATT GAC TGA AAG AA-3′ | 81 | (Dutheil 2009) |

| 18S | NR_003286.2 | 5′-CAC GGC CGG TAC AGT GAA A-3′ | 5′-AGA GGA GCG AGC GAC CAA-3′ | 71 | (Snodgrass 2010) |

Data for q-RT-PCR was displayed utilizing StepOne™ software version 2.3 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Resulting CT values were analyzed and converted to fold differences using the change in Ct between the positive controls and the umbilical cord (2Δ ΔCTmethod) for relative quantitation. Unpaired students t-tests were performed on CT values normalized against 18S as the housekeeping gene using GraphPad Prism version 5.0b for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California).

Protein expression and localization

A subset of 10 samples from the q-RT-PCR studies was analyzed for protein expression and localization, this subset contained all available positive samples for P-gp.

For detection of BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp protein by immunoblotting, SDS-page gels (10%) were used to resolve 20 μg of umbilical cord lysate and each sample was analyzed on at least two separate gels. The proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes using a semi-dry system at 12 V for 45 mins. Membranes were blocked with 5% non fat milk powder in PBS 0.1% Tween-20. Primary polyclonal rabbit anti-BCRP (ab63907, Cambridge, MA) at 1:1000 overnight at 4°C, or monoclonal rat anti-MRP1 (ab3368, Cambridge, MA), and polyclonal rabbit anti-P-gp antibody (ab129450, Cambridge, MA), at 1:2000, for two hours at room temperature, were used. Membranes were washed three times for 10 mins in PBS 0.1 % Tween-20. HRP conjugated secondary antibody of donkey anti-rabbit or donkey anti-mouse, (Jackson Immunolabs, Westgrove, PA) at 1:5000 was then incubated for one hour at room temperature. Membranes were then washed three times for 10 mins in PBS 0.1 % Tween-20. Incubated membranes for one minute in ECL solution before detection on x-ray film.

A representative individual liver lysate (10 μg) was included on every blot to normalize the expression across different membranes. The samples were semi-quantified with Image J 1.48v (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). Briefly images were scanned as tiff files, opened in Image J and converted to 32-bit grey images. An equal sized square box was drawn and mean grey values were determined. Background (mean of 3 readings) was subtracted from each band. Umbilical cord expression was normalized to the liver lysate sample on its own membrane.

Immunohistochemical localization and semi-quantitation of transporter proteins

Immunohistochemistry experiments were performed as previously described by us (Collier et al., 2002a; 2002b). Briefly, sections were de-waxed in xylene and rehydrated through an ethanol gradient (100, 95, 75, 50 and 25% ethanol for 5 min each with a final 5 min in TN buffer (0.1M Tris, 0.15M NaCl)) and incubated overnight in primary antibody (1:100 in 0.1M Tris, 0.15M NaCl with 0.5% non fat milk powder, TNB) at 4 °C. Subsequently, primary antibody was removed and the slides washed 3 × 15 min in 0.1M Tris, 0.15M NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20, TNT). Then secondary antisera (1:500 donkey α rabbit-biotin for P-gp, 1:500 donkey α mouse-biotin for MRP-1 and BCRP) in TNT and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. After incubation, cells were again washed three times in TNT and then streptavidin-HRPO added (1:100 in TNT) was added and incubated for 30 minutes in the dark. A 5 minute wash in TNT was done before adding diaminobenzidine for 10 minutes in the dark, followed by 3 × 15 minute washes in TNT and a 15 minute counter-stain in RICCA-Gill 3 hematoxylin. Destaining was performed by adding 200 uL acid-ethanol destain (30s), followed by a 15 min wash in TNT and repeating the destain. Then, a 2×15 minute wash was done, followed by a quick dip in Scott's tapwater substitutes (30s). Slides were then allowed to air-dry, mounted and coverslipped. Slides were visualized on a Leica DMLB microscope using 100× (10× objective and 10× camera lens) magnification under bright-field illumination.

Pictures were taken with an RSPhotmetrics CoolSnap camera using constant exposure time. Staining density (for semi-quantitation) was determined using image J using area:density analysis with background subtraction. Comparison for quantitation of staining was to tissues that had secondary antibody, Streptavidin-HRPO and DAB treatment, but no primary antibody. The specificity of staining was determined for each antibody in triplicate using the following controls: no primary antibody negative antibody control (performed in triplicate), primary antibody to MMP9 as a positive methodological control for umbilical tissues (in triplicate), human liver and kidney slides treated with each primary antibody (positive controls for detection of ABC transporters).

Semi-quantitation of ABC transporter protein expression

Slides were visualized with a Leica DMLB microscope and pictures taken at 100× power (10× objective and 10× camera lens) with constant exposure, focus and light intensity using a RSPhotometrics CoolSnap camera RGB mode. Separately, a stage-mounted micrometer was photographed at the same settings for sizing images. Photomicrographs were saved as JPEG files. All JPEG files were opened in the Image J program (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) and analyzed under their native image properties. For each sample, 3 images were analyzed with each image quantitated in triplicate fields. Each of the triplicate fields were defined by manually drawing a box (at random) on the picture file. The boxed area was inverted, converting brown DAB staining to blue. Files were then deconvoluted to a RGB stack and the blue channel isolated for analysis. Using the “auto threshold” option, the non-blue (unstained) area and intensity were calculated by allowing the red channel to bleed through and the program to determine the pixel percentage. For determining positive staining, two methods were used: visual inspection and digital calculation. True positives were assigned when both visual inspection and statistical/digital interpretation were in concordance.

After all individual slides and replicates had been analyzed, representative pictures were chosen and the micrometer JPEG was merged with each individual sample JPEG image to demonstrate scale. This file was converted to a TIFF image for presentation and contrast and brightness optimized.

Demographic and Statistical Analyses

Differences in transporter mRNA and protein expression were compared to the following obstetric and neonatal variables: maternal age, parity, gravidity, gestational age, delivery type, smoking status, use of illicit drugs, pre-term labor, Types 1, 2 and gestational diabetes mellitus, pre-eclampsia, infection, neonatal sex, neonatal abnormalities, neonatal chest circumference, neonatal arm length, neonatal head circumference.

It was determined that data were normally distributed using the D'agostino-Pearson Omnibus test for normality (BCRP, MRP1 n = 25 for mRNA and n = 10 protein) or Komolgorov-Smirnoff test for small sample sets (P-gp: n = 5 or 4, respectively). For clinical conditions and demographics with binary outcomes (e.g. sex, delivery method), student's t-tests were performed between groups. Correlations between mRNA or protein expression and continuous variables (e.g. BMI, age etc) were performed using Pearson's correlation. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 5.0 for Mac OsX (Graph Pad Prism, San Diego, CA).

Results

Expression of ABC transporter mRNA in total umbilical cord lysate

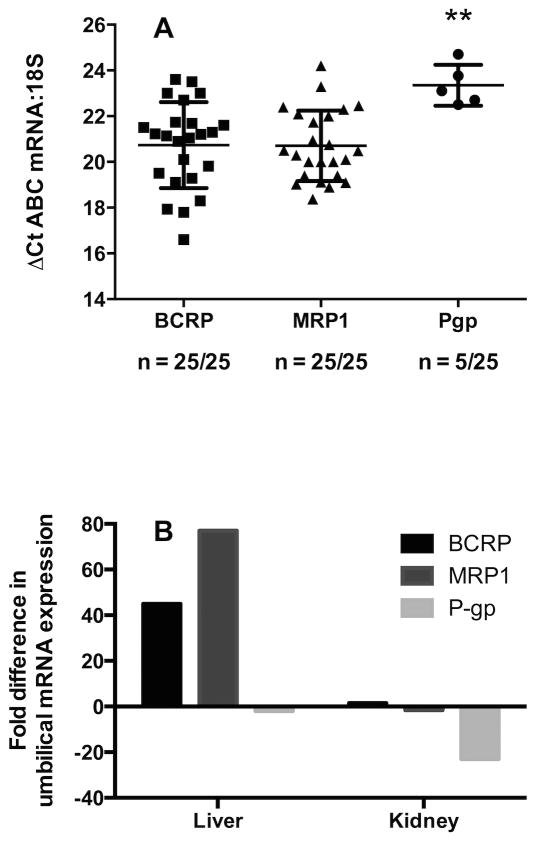

For BCRP and MRP1 mRNA was detected in 25/25 samples. For P-gp, only 5/25 samples were positive for mRNA and then at levels two-fold lower than either BCRP or MRP1 (P < 0.01, Figure 1A). The relative expression levels of transporters in umbilical cord as compared to 18S were delta CT of 20.1 ± 2.5, 20.3 ± 1.7, and 23.3 ± 0.9 for BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp, respectively. To confirm a true negative for the 20 samples in which P-gp was not detected, half of the samples were chosen at random and re-assayed in triplicate, using 8× the levels of cDNA template. These results were also negative.

Figure 1. The mRNA expression of BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp in a cohort of 25 umbilical cords and comparison of relative transporter levels between the umbilical cord and two positive controls (liver and kidney).

1A: The mRNA levels of BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp. The CT values were determined and normalized to 18S to give ΔCT values. ** = P < 0.01, vs. both BCRP and MRP1. Data are plotted as a scatter plot with means ± Standard deviation. 1B: A comparison of the fold differences in mRNA expression of umbilical BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp as compared to mRNA levels in liver and kidney, using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

For the human liver ABC transporter mRNA expression relative to 18S was 25.6 ± 0.3, 26.5 ± 0.6 and 22.2 ± 0.2 for BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp respectively. For human kidney the delta CT values relative to 18S were 20.7 ± 0.05, 19.6 ± 0.04 and 17.7 ± 0.05 for BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp. The mRNA expression of all three transporters is higher in kidney than liver. In the umbilical cord BCRP expression is 45-fold higher than liver and 1.5-fold higher than in kidney, MRP1 was 76-fold higher than human liver and 1.6-fold lower than the kidney. For the 5 samples where P-gp was detected, mRNA expression was 2-fold lower than human liver and 48-fold lower than human kidney (Figure 1B).

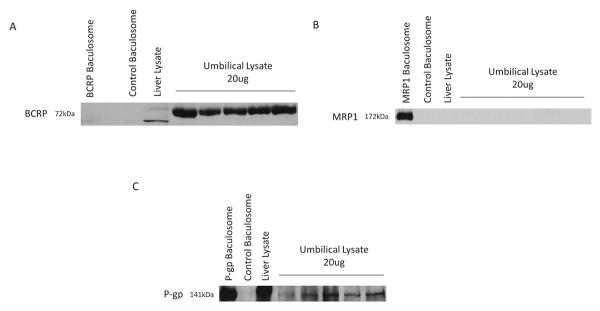

Relative protein expression of ABC transporters in total umbilical cord lysate

Proteins for BCRP were detected by western immunoblot in 10/10 samples and normalized to a single individual liver lysate sample. Relative BCRP expression was 2.32 ± 0.46 mean pixel density, with a 1.9-fold range of 1.58-2.93 (Figure 2A). The expression of P-gp mRNA and protein could only be confirmed in 4 of the 10 samples. Relative P-gp expression was 0.66 ± 0.14 mean pixel density, with a 2-fold range of 0.39-0.79 (Figure 2C). The proteins for MRP1 could not be reliably detected by either immunoblot or IHC (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Representative Western blotting of BCRP, MRP1, and P-gp.

2A: BCRP protein detected by Western blotting and normalized to BCRP levels detected in an individual liver sample. Example of Western blot of five individuals with 20ug umbilical cord lysate loaded compared with an individual liver sample (20ug), and control baculosome. 2B: MRP1 protein detected by western blotting. Example of Western blot of five individuals with 20ug umbilical cord lysate loaded compared with individual liver sample (20ug), MRP1 baculosome (5ug), and control baculosome. 2C: P-gp protein detected by Western blotting and normalized to P-gp levels detected in an individual liver sample. Example of Western blot of five individuals with 20ug umbilical cord lysate loaded compared with individual liver sample (20ug), P-gp baculosome (1ug), and control baculosome.

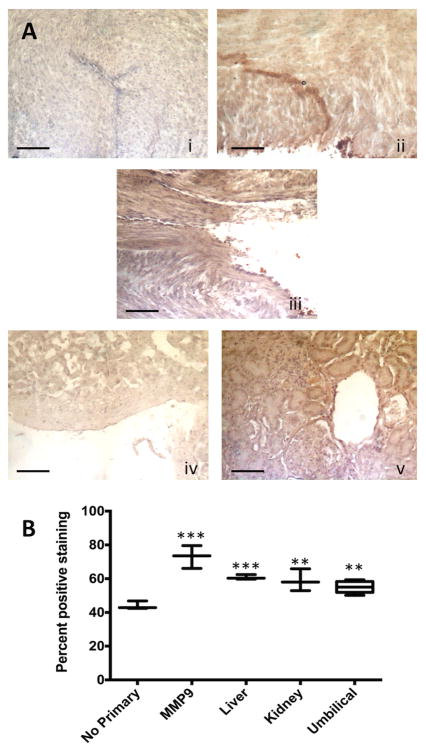

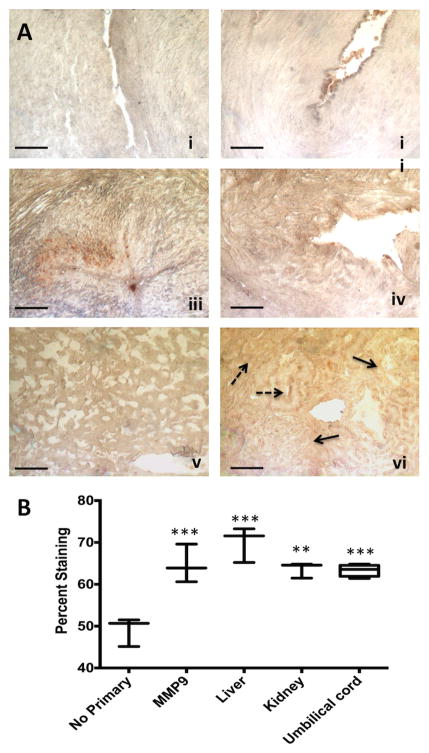

Immunohistochemical expression and localization of ABC transporters

Proteins for BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp were detected in umbilical cords to varying degrees. By eye: 10/10 BCRP, 4/10 MRP1 and 4/10 P-gp samples were graded “positive”. Digitally, significantly higher staining than the negative control was recorded for: 10/10 BCRP, 1/10 MRP1 and 4/10 P-gp. In the 3 cases where the “by eye” analysis was positive but the computer analysis was not (all MRP1), the corresponding digital significance values were P = 0.07, 0.07 and 0.13, respectively. Despite this, slides were only used for further analysis where both visual and digital appraisal concurred.

The BCRP proteins were observed throughout the Wharton's jelly (Figure 3Aii). No specific staining in the venous or arterial endothelia was observed. In addition BCRP was detected in the human liver throughout the hepatocytes and in the human kidney (Figure 3Aiv and 3Av, respectively). Compared to human liver and kidney, the levels of expression of BCRP protein in the umbilical cord were not significantly different (Tukey's post hoc comparison, Figure 3B). The variability in digital quantitation (coefficient of variation, CV) was 6.4 ± 4.7% within images (range 1.3 – 25.5%) and 6.2 ± 3.5% between images (range 1.2 – 12.5%). This indicates variability in staining in different areas of each image, but consistently similar detection between slides.

Figure 3. Immunohistochemical expression and localization of BCRP in human umbilical cords with semi-quantitation of staining for protein levels.

3A: The photomicrographs presented demonstrate the negative control with no primary antibody (i), the positive control antibody (MMP9) shows strong staining in umbilical cords (ii), positive staining for BCRP in one representative umbilical sample (iii) and staining for BCRP in comparison tissues: liver (iv) and kidney (v). Scale bar is 100 μm. The arrows show strong staining in the tubules. 3B: Quantitation of relative levels of DAB staining for BCRP using Image J as detailed in the materials and methods. Boxes show mean (horizontal bar) ± minimum and maximum for n = 3, except for umbilical cords which are n = 10. ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001 vs. no primary negative control.

The P-gp transport protein was detected in 4/10 umbilical cords tested by IHC, and in the liver and kidney (Figure 4A). In the umbilical cord, there was no specific localization to the venous or arterial endothelia (Figure 4A). Moreover, in the Wharton's jelly, staining was routinely punctate, which may indicate localization to macrophages or neutrophils (solid arrows, Figure 4A). Non-specific staining in red blood cells was observed. In the human liver, staining was uniform and moderate throughout the hepatocytes (Figure 4A). In the kidney there was some apparently stronger staining bordering bowman's capsule (solid arrows), although there was staining throughout the tubule cells (broken arrows, Figure 4A). Staining intensity analyses revealed that the liver had stronger staining for P-gp than the umbilical cord (P = 0.05, Tukey) but the kidney did not (Figure 4B). The CV for digital quantitation was 6.0 ± 5.1% within slides (range 0.5 – 15.7 %) and 6.6 ± 3.5% between slides (range 1.2 – 15.8%).

Figure 4. Immunohistochemical expression and localization of P-gp in human umbilical cords with semi-quantitation of staining for protein levels.

4A: The photomicrographs presented demonstrate the negative control with no primary antibody (i), a representative micrograph from an umbilical cord with no positive staining (ii), a representative micrograph of one of the four P-gp positive umbilical samples (iii), the positive control antibody (MMP9) showing strong staining in umbilical cords (iv), and staining for P-gp in comparison tissues: liver (v) and kidney (vi). Solid arrows indicate staining in Bowman's capsule, broken arrows are tubular staining. Scale bar is 100 μm. 4B: Quantitation of relative levels of DAB staining for P-gp using Image J as detailed in the materials and methods. Boxes show mean (horizontal bar) ± minimum and maximum for n = 3, except for umbilical cords which are n = 4. ** = P < 0.01 and *** = P < 0.001, vs. no primary negative control.

When comparing mRNA to protein expression levels detected by IHC, a significant positive correlation for BRCP was observed in the 10 matched samples (P = 0.02, r2 = 0.70, Pearson) which is supported by the Western immunoblot protein data where protein correlated between immunoblot and IHC (P = 0.03, r = 0.67). Similarly for P-gp, even with only 4 samples, a trend towards significance was observed for mRNA and immunoblot protein levels (P = 0.08, r = 0.91, Pearson) and between protein levels from both immunobloting and IHC methods (P = 0.2, r = 0.72) that would likely become significant if more samples were positive. As only a single MRP1 cord tested positive for both mRNA and protein, correlation was not possible.

Effects of demographics and pregnancy syndromes on ABC transporter expression

There were no significant associations observed between mRNA or protein expression for any ABC transporters with any of the demographic and clinical variables.

Discussion

The key findings of this study are that the mRNA expression of the BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp was detected in umbilical cord, but the proteins for these transporters were not always present. The transporter BCRP was transcribed and translated in all human umbilical cords tested, localizing to the Wharton's jelly. Because mRNA expression correlated significantly with the protein expression, this likely indicates that there is basal transcriptional regulation of the transporter's expression. The P-gp transporter was reliably detected with all three methods (RT-PCR, Western immunoblotting and IHC) in only 4/25 samples. Because the correlation of mRNA and protein levels approached significance even with small sample size, this might suggest that P-gp mRNA is transcriptionally up regulated by a discrete stimulus. In contrast, MRP1 mRNA was detected in all 25 umbilical cords tested, but the protein could not be reliably detected by immunoblotting or IHC. Therefore, ubiquitous low-level transcription of MRP1 does not seem to be matched with global translation of the protein. This is the first study to present both mRNA and protein data for these ABC transporters in the umbilical cord, and to localize the proteins in the cord. We have demonstrated that mRNA screening alone is not appropriate for indicating whether transporter proteins are present and that the presence of ABC transporters can be variable by individual tissue sample and by transporter type.

While the placenta is critical for fetal detoxification and well-being, a case can be made that the umbilical cord is closer to the fetus than the placenta, and presents the proximate site for fetal protection. The human umbilical vein endothelial (HUVEC) cell line does not constitutively express P-gp mRNA or protein (Iwahana et al., 1998) but mRNA expression of both BCRP and MRP1 has been demonstrated (Dauchy et al., 2009) with biochemical evidence for active MRP1-mediated transport (Snyder et al., 2013). Although HUVECs are an interesting model, this cell line contains a number of abnormalities due to its immortalized nature, necessitating caution in predicting in vivo expression and localization from this model. In the placenta, P-gp is highly expressed in first trimester, but declines towards term (Gil et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2006). This is a potential explanation for the variable levels of P-gp we observed in the umbilical cord, as these were all from term deliveries. However, data for BCRP and MRP1 are less well defined with respect to gestational changes. In umbilical tissue itself, prior to this study, there was a single report of the presence of ABC transporters, where mRNA for the BCRP transporter was observed in Wharton's jelly (Montanucci et al., 2011). We have confirmed the findings of Montanucci et al. and expanded upon them by demonstrating presence of the BCRP protein. More recently, a comprehensive study of hepatic biomarkers in Wharton's jelly demonstrated that Wharton's jelly tissue is replete with transcriptional factors involved in liver development, including transporters; but not adult markers of metabolism such as the P450s and the hepatic nuclear factors (Buyl et al., 2014). This has implications as to whether these proteins have a function in the umbilical cord, or are an artifact of developmental biology. Because the umbilical cord is a rich source of stem cells, it is possible that these ABC proteins are not inherently functional but are present for future functions of differentiated cells. This would be another explanation for why we observe expression of mRNA but not protein for MRP1 and/or P-gp. The ideal study would characterize transporter protein function in umbilical cords, but this is not possible in archival human tissues, and would need to be performed in cell culture monolayers or an artificial membrane system.

The localization of the transporters is also of interest. It was surprising that the proteins did not localize to the arterial or venous endothelia. This led us to speculate that transporters may exist to export chemicals that have passively diffused into the cord, out into the amniotic fluid. Since the umbilical cord plays a critical role in fetal circulatory pressure this would presumably protect the fetal cardiovascular system and umbilical cord functions (Rankin et al., 1980). Moreover, there are many enzymatic systems that are active in the fetal liver at levels as great or greater than the adult including some Sulfotransferases and Cytochromes P450 (Myllynen et al., 2009; Richard et al., 2001). Therefore substances transported into amniotic fluid might be detoxified by the fetal liver via natural fetal swallowing of the fluid that occurs.

The BCRP, P-gp and MRP1 transporters have very broad substrate specificities that substantially overlap with each other, but each has individual selectivities (Mao and Unadkat, 2015). In general BCRP and P-gp share commonalities in tissue distribution and expression, although MRP1 is less similar and far less studied (Mao and Unadkat, 2015). They are considered to be the three major ABC transporters responsible for multidrug resistance in cancer and for altering drug disposition through efflux transport (Mao and Unadkat, 2015). The major finding of this study was the high levels of expression of BCRP and variable expression of P-gp proteins in the umbilical cord. Since these are known to be specifically efflux transporters, and were not localized to venous or arterial endothelia, this provides some support for our speculation that expression in the Wharton's jelly of the umbilical cord may exist to remove substances that have diffused in from the amniotic fluid.

In humans, BCRP and P-gp are highly expressed in placental syncytiotrophoblasts, the intestinal epithelium, hepatocytes, in kidney proximal tubules and at the blood:brain barrier (Mao and Unadkat, 2015). High levels of expression in these organs is associated with the organs' metabolic and elimination functions. Although much of the original study of BCRP and P-gp were in the context of cancer where high expression is associated with poor clinical outcomes, recently their roles in other conditions, including pregnancy have received more interest (Natarajan et al., 2012). In pregnancy, changes in placental ABC transporters (primarily BCRP and P-gp) have been associated with preterm birth, pre-eclampsia, growth restriction and infection (Iqbal et al., 2012). Here we did not see any relationship to these conditions in the umbilical cord, but this was primarily due to low numbers of cords from complicated pregnancies. Definitive elucidation of this would require a larger cohort. Additionally, it is highly likely that in pregnancy ABC transporters are regulated differentially across gestation because the proteins are responsive to a number of nuclear transcription factors that can be activated by hormones. Because fluctuating steroid hormones are a hallmark of pregnancy, including progesterone, estrogen and corticosteroids, these likely differentially regulate expression of BCRP, MRP1 and P-gp in gestational tissues (Iqbal et al., 2012). This changing steroidal environment could be a plausible reason that studies on P-gp demonstrate a decline in expression across gestation (Gil et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2006). Future studies in gestational tissues such as placenta, umbilical cord and endo-or myometrium should seek to determine the role of hormonal signaling on ABC transporter expression during pregnancy.

Conclusions

The presence of mRNA and protein of the transporters BCRP and P-gp in the Wharton's jelly of human umbilical cords has been confirmed. Although BCRP mRNA and proteins were ubiquitously present, P-gp mRNA appeared in only a subset of samples (∼25%) while protein could be reliably detected in 20% of samples tested. Finally, although MRP1 mRNA was routinely detected, MRP1 proteins were not. These studies highlight the importance of performing protein studies in support of mRNA expression studies. Understanding transporter dynamics in umbilical tissues will be vital for validating umbilical cords as more than just a binary “yes/no” screen for drug presence and determining their suitability for quantitation of drug levels. Although, it must be stated that this study has not given any data on transporter functions (dynamics) and so the flow of chemicals cannot be divined from the mRNA and protein expression studies. Future work should focus on the functional properties of these proteins in gestational tissues. Ultimately, quantifying fetal exposure requires accurate information about drugs and other chemical levels in maternal blood, placenta, umbilical cord, fetal blood/tissues and amniotic fluid. In addition, determining the relative flow between these compartments will allow development of predictive pharmacokinetic and exposure models.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by NIH MD007601. Funding bodies did not influence publishing.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to declare.

References

- Ahmed F, Arseni N, Glimm H, et al. Constitutive expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2 enhances the growth potential of early human hematopoietic progenitors. Stem Cells. 2008;26:810–8. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt R, Wilhelm F, Pelz-Ackermann O, et al. ABCG2 expression is correlated neither to side population nor to hematopoietic progenitor function in human umbilical cord blood. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzaroli F, Mennone A, Feletti V, et al. Clinical trial: modulation of human placental multidrug resistance proteins in cholestasis of pregnancy by ursodeoxycholic acid. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1139–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beghin D, Delongeas J, Claude N, et al. Comparative effects of drugs on P-glycoprotein expression and activity using rat and human trophoblast models. Toxicol in vitro. 2010;24:630–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benirschke K, Kaufmann P. Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Borst P, Elferink R. Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease. Ann Rev Biochem. 2002;71:531–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102301.093055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyl K, Kock JD, Najar M, et al. Characterization of hepatic markers in human Wharton's Jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Toxicol in vitro. 2014;28:113–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier A, Ganley N, Tingle M, et al. UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activity, expression and cellular localization in human placenta at term. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002a;63:409–19. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier A, Tingle M, Paxton J, Mitchell M, Keelan J. Metabolizing enzyme localization and activities in the first trimester human placenta: the effect of maternal and gestational age, smoking and alcohol consumption. Hum Reprod. 2002b;17:2564–72. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.10.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui T, Liu Y, Men V, et al. Bile acid transport correlative protein mRNA expression profile in human placenta with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:1406–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauchy S, Miller F, Couraud P, et al. Expression and transcriptional regulation of ABC transporters and cytochromes P450 in hCMEC/D3 human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil F, Dauchy S, Diry M, et al. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in the normal human brain: regional and cellular mapping as a basis for putative roles in cerebral function. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:1528–38. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evseenko D, Paxton J, Keelan J. ABC drug transporter expression and functional activity in trophoblast-like cell lines and differentiating primary trophoblast. Am J Physiol: Reg Integrat Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1357–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00630.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evseenko D, Paxton J, Keelan J. Independent regulation of apical and basolateral drug transporter expression and function in placental trophoblasts by cytokines, steroids, and growth factors. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:595–601. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinshtein V, Holcberg G, Amash A, et al. Nitrofurantoin transport by placental choriocarcinoma JAr cells: involvement of BCRP, OATP2B1 and other MDR transporters. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;281:1037–44. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedeon C, Anger G, Piquette-Miller M, Koren G. nitrofurantoin Breast cancer resistance protein: mediating the trans-placental transfer of glyburide across the human placenta. Placenta. 2008;29:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil S, Saura R, Forestier F, Farinotti R. P-glycoprotein expression of the human placenta during pregnancy. Placenta. 2005;26:268–70. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemauer S, Patrikeeva S, Wang X, et al. Role of transporter-mediated efflux in the placental biodisposition of bupropion and its metabolite, OH-bupropion. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1080–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodyl N, Stark M, Butler M, Clifton V. Placental P-glycoprotein is unaffected by timing of antenatal glucocorticoid therapy but reduced in SGA preterm infants. Placenta. 2013;34:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Yamasaki K, Homemoto M, et al. Efflux transporter mRNA expression profiles in differentiating JEG-3 human choriocarcinoma cells as a placental transport model. Pharmazie. 2012;67:86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal M, Audette MC, Petropoulos S, Gibb W, Matthews SG. Placental drug transporters and their role in fetal protection. Placenta. 2012;33:137–42. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwahana M, Utoguchi N, Mayumi T, Goryo M, Okada K. Drug resistance and P-glycoprotein expression in endothelial cells of newly formed capillaries induced by tumors. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:2977–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Audus K. Effect of bisphenol A on drug efflux in BeWo, a human trophoblast-like cell line. Placenta. 2005;26:S96–S103. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J, Jones M, Jones B, et al. Detection of codeine, morphine, 6-monoacetylmorphine, and meconin in human umbilical cord tissue: method validation and evidence of in utero heroin exposure. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37:45–52. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolwankar D, Glover D, Ware J, Tracy T. Expression and function of ABCB1 and ABCG2 in human placental tissue. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:524–9. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummu M, Sieppi E, Wallin K, et al. Cadmium inhibits ABCG2 transporter function in BeWo choriocarcinoma cells and MCF-7 cells overexpressing ABCG2. Placenta. 2012;33:859–65. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmann T, Mauerer R, Zahn A, et al. Real-time reverse transcription-PCR expression profiling of the complete human ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily in various tissues. Clin Chem. 2003;49:230–8. doi: 10.1373/49.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarland A, Abramovich D, Ewen S, Pearson C. Stage-specific distribution of P-glycoprotein in first-trimester and full-term human placenta. Histochem J. 1994;26:417–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00160054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manceau S, Giraud C, Declèves X, et al. ABC drug transporter and nuclear receptor expression in human cytotrophoblasts: influence of spontaneous syncytialization and induction by glucocorticoids. Placenta. 2012;33:927–32. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Q, Unadkat JD. Role of the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in drug transport--an update. AAPS J. 2015;17:65–82. doi: 10.1208/s12248-014-9668-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra P, Audus K. MRP isoforms and BCRP mediate sulfate conjugate efflux out of BeWo cells. Int J Pharmaceut. 2010;384:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montanucci P, Basta G, Pescara T, et al. New simple and rapid method for purification of mesenchymal stem cells from the human umbilical cord Wharton jelly. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2651–61. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllynen P, Immonen E, Kummu M, Vähäkangas K. Developmental expression of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporter proteins in human placenta and fetal tissues. Exp Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:1483–99. doi: 10.1517/17425250903304049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashige M, Ushigome F, Koyabu N, et al. Basal membrane localization of MRP1 in human placental trophoblast. Placenta. 2003;24:951–8. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(03)00170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K, Xie Y, Baer MR, Ross DD. Role of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in cancer drug resistance. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1084–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascolo L, Fernetti C, Garcia-Mediavilla M, Ostrow J, Tiribelli C. Mechanisms for the transport of unconjugated bilirubin in human trophoblastic BeWo cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:94–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02357-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascolo L, Fernetti C, Pirulli D, et al. Effects of maturation on RNA transcription and protein expression of four MRP genes in human placenta and in BeWo cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2003;303:259–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00327-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollex E, Anger G, Hutson J, Koren G, Piquette-Miller M. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)-mediated glyburide transport: effect of the C421A/Q141K BCRP single-nucleotide polymorphism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:740–4. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.030791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin J, Stock M, Anderson D. Fetal heart rate and umbilical blood flow. J Development Physiol. 1980;2:11–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard K, Hume R, Kaptein E, et al. Sulfation of thyroid hormone and dopamine during human development: ontogeny of phenol sulfotransferases and arylsulfatase in liver, lung, and brain. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2734–42. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridano M, Racca A, Flores-Martín J, et al. Chlorpyrifos modifies the expression of genes involved in human placental function. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33:331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y, Yang S, Jee M, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells protect against neuronal cell death and ameliorate motor deficits in Niemann Pick type C1 mice. Cell Transplantation. 2011;20:1033–47. doi: 10.3727/096368910X545086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass R, Collier AC, Coon AE, Pritsos CA. Mitomycin C inhibits ribosomal RNA: a novel cytotoxic mechanism for bioreductive drugs. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19068–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder N, Revello S, Liu X, Zhang S, Blair I. Cellular uptake and antiproliferative effects of 11-oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid. Journal Lipid Res. 2013;54:3070–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M040741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara I, Kataoka I, Morishita Y, et al. Tissue distribution of P-glycoprotein encoded by a multidrug-resistant gene as revealed by a monoclonal antibody, MRK 16. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1926–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Kingdom J, Baczyk D, et al. Expression of the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein, (ABCB1 glycoprotein) in the human placenta decreases with advancing gestation. Placenta. 2006;27:602–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Souza K, Diamond H, Ornellas M, et al. Rhodamine 123 efflux in human subpopulations of hematopoietic stem cells: comparison between bone marrow, umbilical cord blood and mobilized peripheral blood CD34+ cells. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Unadkat J, Mao Q. Hormonal regulation of BCRP expression in human placental BeWo cells. Pharmaceut Res. 2008;25:444–52. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9432-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright TE, Milam K, Rougee LR, Tanaka M, Collier AC. Agreement of umbilical cord drug and cotinine levels with maternal self-report of drug use and smoking during pregnancy. J Perinatol. 2011;31:324–9. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S, Itagaki S, Hirano T, Iseki K. Effects of sex hormones on regulation of ABCG2 expression in the placental cell line BeWo. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeboah D, Sun M, Kingdom J, et al. Expression of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in human placenta throughout gestation and at term before and after labor. Canadian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;84:1251–8. doi: 10.1139/y06-078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wen Z, Lan S, et al. The AFT024 stromal cell line improves MDR1 gene transfer to CD34+ cells derived from human umbilical cord blood. Neoplasma. 2007;54:21–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]