Abstract

Background

Social cognition is not routinely assessed in older adults. We report population-based normative data on the Social Norms Questionnaire (SNQ22) which asks individuals about the appropriateness of specific behaviors in hypothetical scenarios, errors being related either to breaking with norms or to over-adhering to perceived norms. Total SNQ scores represent the number of correct responses while subscale scores are error totals.

Methods

We administered the SNQ22 to 744 adults aged 65+ within a population-based study, and examined the distribution of scores by demographics, other cognitive measures, and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).

Results

Most participants performed well with few errors. Women and young-old individuals performed significantly better than men and older individuals on total score and over-adherence; women had fewer break-norms errors than men. No race or education effects were observed. Worse (higher) total scores and (lower) over-adherence errors were inversely associated with literacy, CDR, MMSE, attention, memory, language, executive, and visuospatial domains. Break-norms errors were rare and not associated with any of the above

Conclusions

In population-based normative data on the SNQ22. age and gender influenced total score and over-adherence errors, which showed the expected associations with CDR and other cognitive domains. Social norms screening may be useful in the cognitive assessment of older adults.

Social cognition is a critical aspect of human behavior which is required to develop and maintain the interpersonal relationships, and participate in the social interactions, that allow individuals to function within society. 1, 2 It has been included for the first time in DSM-5 as one of the cognitive domains to be assessed for the diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders. 3 The domain of social cognition has had an increasing influence on cognitive neuroscience, and highlights the characterization of the “social brain” and the parameters of normal and aberrant behavior.4 It includes the areas of affective empathy, theory of mind (the ability to represent others’ mental states), social perception, and social behavior.1 Social cognition has been traditionally assessed in research and specialty clinical settings focused on frontal lobe dysfunction in both neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders, ranging from autism to schizophrenia to frontotemporal dementia (FTD). Typically, these abilities are impaired early in frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and autism in which they are core diagnostic criteria. They are considered relatively preserved early in Alzheimer disease (AD) where they can eventually also become prominent concerns, but social cognitive symptoms have also been reported in early AD.5 Thus, most studies of social cognition have been conducted in young to middle aged to young-old individuals with the above disorders. Social cognition has not thus far been a target for assessment in the general geriatric clinical setting or in population screening.

As an example of impaired social cognition, individuals affected by the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) characteristically ignore or flout social norms in everyday life. To measure appreciation of prevailing social norms, the Social Norms Questionnaire (SNQ22) is part of the battery called NIH EXAMINER (Executive Abilities: Measures and Instruments for Neurobehavioral Evaluation and Research).6 This test requires individuals to identify appropriate and inappropriate behaviors in several hypothetical scenarios. It has been found useful to distinguish patients with Alzheimer disease from patients with bvFTD who typically have difficulty with this task; 7 it is debatable whether the latter fail to recognize the social rules or merely choose to flout them.8

However, perceptions of normative or appropriate social behavior can potentially vary across generational and cultural subgroups, as well as by age and gender and possibly education. To our knowledge, there are no population-based normative data on the SNQ22 in older adults. We administered the SNQ22 within an ongoing population-based cohort study of aging and examined the distribution of test performance by demographic and cognitive characteristics. Given that the SNQ22 is included in the frontotemporal lobar degeneration protocol8 of the Uniform Data Set (UDS) of the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center, our data may provide useful normative information for investigators conducting clinical research using this test.

METHODS

Study site and population

Our study cohort, named the Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT), is an age-stratified random population sample drawn from the publicly available voter registration list for a small-town region of Pennsylvania (USA). As previously reported, community outreach, recruitment, and assessment protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB. Recruitment criteria were (a) age ≥65 years, (b) living within the selected towns, (c) not already in long-term care institutions. Individuals were ineligible if they (d) were too ill to participate, (e) had severe vision or hearing impairments, (f) were decisionally incapacitated. All initially recruited 2036 participants provided written informed consent during recruitment. As the project was designed to study mild impairment, we screened out those who, at study entry, exhibited substantial impairment by scoring <21/30 on the age-education-corrected Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). 10,11 The remaining 1,982 individuals were representative of older adults in the targeted communities, with age range 65–99 years and mean (SD) age of 77.6 (7.4) years; they were 61.0% female; 94.7% of mixed European descent, with a median educational level of high school graduate.9 Participants underwent repeat assessments at annual data collection “waves.” Here we restrict our analyses to Wave 9, when we first administered the SNQ22.

Assessments

Cognitive assessments and domains

At baseline and at each annual wave, we assessed cognitive functioning using the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) 10, 11 and also a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests tapping fivecognitive domains: attention/processing speed (Digit Span, Trailmaking Test A), executive function (Trailmaking Test B, Clock Drawing, Letter Fluency), memory (Logical Memory, immediate and delayed recall; Visual Reproduction, immediate and delayed recall; Object Memory Evaluation), language (Boston Naming Test, Animal Fluency, IU Token Test), and visuospatial function (Block Design), as previously reported.12 Norms on these tests in our study cohort may be viewed at http://www.dementia-epidemiology.pitt.edu/MYHAT/MYHAT_Norms.html.

To create a composite score for each cognitive domain, we transformed each individual test score into a standardized score by centering to its mean value and dividing by its standard deviation, and then calculated the arithmetic mean of all the standardized scores in each domain.13 At baseline we also administered the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) 14 as a measure of premorbid intellectual ability and the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) 15 as a test of literacy.

Clinical Dementia Rating

At study entry (baseline) and at each annual data collection wave, we assessed cognitively driven everyday functioning to rate participants on the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale 16, independent of neuropsychological test performance.12

Social Norms Screening

At Wave 9, we introduced a 22-point screening scale called the Social Norms Questionnaire (SNQ22) 6, 7, which asks individuals to identify inappropriate behaviors in several hypothetical scenarios. They are presented with 22 behaviors in specific situations and asked whether each one would be appropriate in the presence of an acquaintance who is not a close friend, according to the mainstream culture of the United States. Individuals can potentially make two kinds of errors, “over-adherence” when they indicate something is socially inappropriate but it really is not, such as eating ribs with one’s fingers or laughing when they themselves trip and fall; and “break norms” errors where individuals indicate it is appropriate to do something which is not, like eating pasta with one’s fingers or laughing at others when they trip and fall. A total SNQ22 score is the sum of correct responses (i.e., lower score is worse), whereas the subscale scores are the sums of errors (i.e., higher scores are worse).

Statistical Methods

We first examined the overall frequencies with which each SNQ22 item was correctly answered, and then the mean values of total and subscale scores by age groups, gender groups, race groups, educational groups, and CDR levels of 0 (no dementia), 0.5 (mild cognitive impairment or very mild dementia), and ≥1 (at least mild dementia). Next, we examined the association of scores with MMSE, WRAT, WTAR, and five cognitive domains of attention, memory, language, visuospatial, and executive functions. We also summarized the calculated scores by age, gender, education, and race in individuals free of dementia (CDR <1) to serve as normative data.

As the distributions across the sample of SNQ22 total score and the two error scores (over-adherence and break-norms) were highly skewed, we used non-parametric statistics to examine the relationships of these scores with the variables of interest. For the categorical variables (age groups, gender groups, race groups, education groups, and CDR levels) we used Wilcoxon rank-sum tests where there were 2 categories and Kruskal-Wallis tests where there were 3 categories. Where Kruskal-Wallis tests were significant, we conducted post-hoc analyses using Dunn’s test to identify significant pairwise comparisons. For the continuous variables (MMSE, WTAR, WRAT, and cognitive domain composite scores for attention/processing speed, executive functioning, memory, language, and visuospatial functioning), we calculated Spearman correlation coefficients, setting the statistical significance level at p <0.01.

RESULTS

At Wave 9, 745 individuals had complete data on the variables of interest. Their mean (SD) age was 84.3 (6.6) years; 65.2% were women; 95.2% were of European descent. Their median educational level was high school graduate; 9.3% were below the educational median, 41.2% were at the median, and 48.9 % had more than high school education. Their mean (SD) MMSE score was 26.72 (4.14); their mean (SD) WRAT score was 105.49 (8.40) and their mean (SD) WTAR score was 104.65 (12.53)

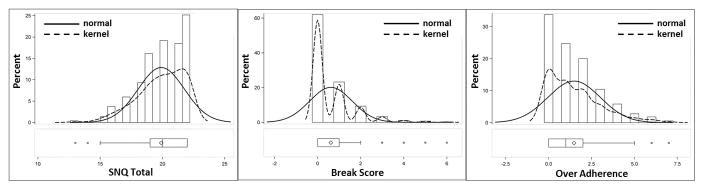

The distributions of the total SNQ22 score, over-adherence subscale, and break norms subscale, were all extremely skewed (Figure 1), i.e., most participants made few errors, as would be expected in a largely normal population. The median score (inter-quartile ranges) for total SNQ22 over-adherence subscale, and break-norms subscales were 20 (19–22), 1 (0–2), and 0 (0–1).

Figure 1.

Distributions of Total SNQ22 scores and both Error Subscale scores

The overall frequencies with which each SNQ22 item was correctly answered, i.e., as socially appropriate (normative) or not appropriate (non-normative) (Table 1) showed that the most and least frequently endorsed items were wearing the same shirt twice in one week (91.4%) (normative) and talking out loud during a movie in a theater (0.4%) (non-normative). The non-normative item most frequently endorsed (17.8%) was asking a co-worker their age.

Table 1.

SNQ22 items and overall frequency of endorsement

| SNQ22 item | Number of participants answering “yes”: n (%) * | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tell a stranger you don’t like their hairstyle | 18 (2.4) * |

| 2 | Spit on the floor | 8 (1.1) * |

| 3 | Blow your nose in public | 558 (77.6) |

| 4 | Ask a co-worker their age | 128 (17.8) * |

| 5 | Cry during a movie in a theater | 631 (87.8) |

| 6 | Cut in line if in you’re in a hurry | 22 (3.1) * |

| 7 | Laugh when you yourself trip and fall | 561 (78.0) |

| 8 | Eat pasta with your fingers | 36 (5.0) * |

| 9 | Tell co-worker your age | 637 (88.6) |

| 10 | Tell someone your opinion of a movie they haven’t seen | 532 (74.0) |

| 11 | Laugh when someone else trips and falls | 45 (6.3) * |

| 12 | Wear the same shirt every day | 56 (7.8) * |

| 13 | Keep money you find on the sidewalk | 636 (88.5) |

| 14 | Pick your nose in public | 7 (1.0) * |

| 15 | Tell coworker you think they are overweight | 28 (3.9) * |

| 16 | Eat ribs with your fingers | 652 (90.7) |

| 17 | Tell a stranger you like their hairstyle | 634 (88.2) |

| 18 | Wear same shirt twice in 2 weeks | 657 (91.4) |

| 19 | Tell someone the ending of movie they haven’t seen | 29 (4.0) * |

| 20 | Hug a stranger without asking | 63 (8.8) * |

| 21 | Talk out loud during movie in theater | 3 (0.4) * |

| 22 | Tell coworker you think they have lost weight | 627 (87.2) |

Asterisks indicate items where “yes” is the incorrect (non-normative) response and contributes to the break-norms error score. In the remaining items, “yes” is the correct (normative) response; responses of “no” are errors contribute to over-adherence error score.

In online supplemental tables 1–5, we provide item-by-item response frequencies by age, gender, race, and education groups among individuals without dementia (CDR <1), and also show comparisons between individuals with CDR=0 and CDR=0.5. European Americans were significantly more likely than African Americans to say it was appropriate to laugh when they themselves trip and fall (p=0.03), and to wear the same shirt twice in two weeks (p=0.0087). Individuals aged 75–84 were significantly more likely than those aged 85+ to say it was appropriate to laugh when they themselves trip and fall (p=0.0007) and to keep money one finds on the sidewalk (p=0.0051). People with less than high school education were less likely than better educated individuals to say it was appropriate to tell a co-worker one’s own age (p=0.0014). With respect to gender, there were multiple differences. Women were more likely than men to provide “correct” responses to asking a co-worker their age (p=0.037), crying during a movie in a theater (p<0.001), eating pasta with one’s fingers (p=0.0032), wearing the same shirt every day (p=0.0113), telling a co-worker that they are overweight (p<0.0001), telling a stranger that one likes their hairstyle (p<0.0001), telling someone the ending of a movie they haven’t seen (p=0.0005), and telling a co-worker that one thinks they have lost weight (p<0.0001). Individuals with mild cognitive impairment (CDR=0.5), compared to those with normal cognition (CDR=0), were more likely to make over-adherence errors by saying it was inappropriate to laugh when they themselves trip and fall (p=0.001), and to tell someone one’s opinion of a movie they haven’t seen (p=0.016).

Comparing the distributions of total and subscale scores by demographic groups (Table 2) (at a significance level of p<0.01), women and young-old individuals performed significantly better than men and older individuals, respectively, on total score and over-adherence score. Women made fewer break-norms errors than men. No race or education effects were observed. Worse total and over-adherence scores were associated with higher CDR levels..

Table 2.

SNQ22 total and error scores by demographics and Clinical Dementia Rating

| Characteristics | n | Total SNQ22: Mean (SD) | p-value* | Over-adherence errors: Mean (SD) | p-value* | Break–norms errors: Mean (SD) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Wave 9. | 65–74 | 45 | 20.38 (1.64) | <0.0001 ** | 1.07 (1.32) | <0.0001** | 0.56 (0.78) | 0.4293 |

| 75–84 | 342 | 20.90 (1.70) | 1.22 (1.33) | 0.59 (1.02) | ||||

| 85+ | 358 | 19.56 (1.98) | 1.79 (1.68) | 0.65 (0.98) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 259 | 19.41 (1.92) | <0.0001 | 1.78 (1.53) | 0.0001 | 0.81 (1.13) | 0.0001 |

| Female | 486 | 20.17 (1.78) | 1.32 (1.51) | 0.51 (0.89) | ||||

| Race | White | 709 | 19.94 (1.84) | 0.0443 | 1.46 (1.51) | 0.0943 | 0.61 (0.98) | 0.3609 |

| Other | 36 | 19.21 (2.13) | 2.00 (1.91) | 0.79 (1.17) | ||||

| Education | < HS | 74 | 19.60 (2.19) | 0.4950 | 1.74 (1.79) | 0.5467 | 0.66 (0.99) | 0.9145 |

| = HS | 307 | 19.91 (1.80) | 1.50 (1.54) | 0.59 (0.94) | ||||

| > HS | 364 | 19.96 (1.86) | 1.42 (1.47) | 0.63 (1.03) | ||||

| CDR | 0 | 544 | 20.13 (1.66) | <0.0001** | 1.29 (1.37) | <0.0001** | 0.58 (0.94) | 0.5589 |

| 0.5 | 171 | 19.39 (2.15) | 1.90 (1.72) | 0.71 (1.12) | ||||

| ≥ 1 | 30 | 18.33 (2.44) | 2.96 (2.23) | 0.71 (1.04) |

p-values based on non-parametric tests; Wilcoxon rank-sum or Kruskal-Wallis as appropriate.

post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni-adjusted p-value of 0.0167 were significant (i) for Total SNQ22: age 75–84 vs. age 85+; CDR=0 vs. CDR =0.5, and CDR =0 vs. CDR >=1;

(ii) for Over-adherence subscale: age 65–74 vs. age 85+ and age 75–84 vs. 85+; CDR=0 vs. CDR=0.5 and CDR=0 vs. CDR >=1.

We also looked at the associations of SNQ22 scores with MMSE, WRAT, WTAR, and five cognitive domain composites (Table 3). Worse (higher) total scores and (lower) over-adherence errors were inversely associated with WRAT, WTAR, MMSE, attention, memory, language, and executive functions. Break-norms errors were rare and not associated with any of the above at a significance level of p<0.01, although there were weaker associations (p<0.05) with MMSE, WRAT, executive, language, and memory functions.

Table 3.

SNQ22 total and error scores by other cognitive measures and domain composites

| Spearman correlation coefficient (p-value) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE1 | WTAR2 | WRAT3 | Attention/processing speed | Executive function | Language function | Memory function | Visuospatial function | |

| SNQ22 Total score | 0.19 (<0.001) | 0.36 (<0.001) | 0.11 (<0.001) | 0.21 (<0.001) | 0.26 (<0.001) | 0.22 (<0.001) | 0.23 (<0.001) | 0.13 (0.0092) |

| Overadherence error score | −0.19 (<0.001) | −0.13 (<0.001) | −0.09 (0.0138) | −0.22 (<0.001) | −0.26 (<0.001) | −0.22 (<0.001) | −0.24 (<0.001) | −0.15 (0.0033) |

| Break-norms error score | −0.09 (0.0124) | −0.07 (0.0665) | −0.08 (0.0404) | −0.06 (0.1242) | −0.09 (0.0175) | −0.09 (0.018) | −0.09 (0.0217) | −0.01 (0.7726) |

MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination

WTAR: Wechsler Test of Adult Reading

WRAT: Wide Range Achievement Test

DISCUSSION

In a population-based sample of older adults in small-town U.S. communities, we administered the Social Norms Questionnaire (SNQ22) to obtain normative descriptive data on this measure which thus far has only been used in specialized clinical and research settings. In this cross-sectional study, we found that better total scores and lower over-adherence error scores were associated with higher literacy and premorbid intellectual ability, lower dementia rating, and higher scores in all the cognitive domains. These findings demonstrate the cognitive relevance of social norms measures. Further, our data help validate the normative nature of “correct” (i.e., socially appropriate) responses on the scale, given that the majority of participants in our population-based sample performed well with few errors. This conclusion is further reinforced by the rarity in this older sample of the break-norms errors which are considered typical of bvFTD. This being a non-clinical sample, the proportion of individuals with dementia (as measured by CDR ≥1) was low (4%), and, given the sample’s mean age of 84 years, the likelihood of FTD being present was miniscule.

Unlike break-norms errors, over-adherence errors are relatively non-specific and described as possibly due to anxiety, confusion, inattention, and general cognitive deficits.8 Our data suggest that scores are also affected by demographics; in our sample, the total score and the over-adherence error scores followed identical patterns of associations, i.e., of inferior performance being related to greater age and male gender. Previous work which documented age-related decrements in social cognition studied tasks related to empathy and theory of mind rather than on awareness of social norms.17 The possibility should be considered that apparent age-related findings may relate to cohort or generational effects rather than to the aging process per se. Our findings regarding gender are consistent with most previous studies of gender effects in social cognition, albeit in younger people, that have shown better performance in social cognition tasks among girls compared to boys, a pattern that remains stable at least into early adulthood.4 However, the gender difference in our population-based sample is at odds with the lack of gender difference in SNQ22 scores reported in the original EXAMINER normative sample.6

Of note, we observed no effects of educational level or race on total or subscale scores, acknowledging that the proportion of non-white individuals was small; these negative findings suggest that the scale could be used in American populations with a range of educational levels. Our study participants, drawn from the voter registration lists of a small-town area of the US, are long-term residents of these communities and do not include more diverse or recent immigrant groups; thus, our sample does not allow us to investigate cultural determinants of non-normative performance on the SNQ22. We did observe that almost 18% of the overall sample thought it was appropriate to “ask a co-worker their age,” suggesting that this behavior might not be quite as non-normative as originally proposed; we also observed that somewhat fewer men (78.5%) than women (84.2%) identified this item as inappropriate. The many individual items on which women outperformed men on the SNQ22 raises the question of whether the same norms (e.g.., crying in a movie theater) equally apply to men and women. It certainly seems plausible that there might be different social norms in different parts of the world. For example, whether it is appropriate to comment on others’ appearance at all, and specifically about whether they appear to have lost or gained weight, might depend on what is considered the more attractive body habitus in a given society. Similarly, different questions would be needed for societies that consume neither pasta nor ribs, or eat only with their fingers or chopsticks. Social norms measures should be appropriately validated and calibrated for any population in which they are to be employed for clinical or research purposes.

Awareness of social norms is, of course, only one aspect of social cognition. Others commonly assessed functions include affective empathy and theory-of-mind (ToM) measures which were not included in our study but are the basis of much of the existing literature.1 Frith and Frith18 preface a comprehensive review of the mechanisms of social cognition by stating that “social cognitive neuroscience needs to break away from a restrictive phrenology that links circumscribed brain regions to underspecified social processes.” Sollberger and colleagues exhaustively reviewed the neural substrates of social cognition and concluded that it is less important to localize these functions to a single brain region than to identify the interactive neural networks that underpin them.19 This was in fact the approach taken by Moran and colleagues who have examined the effect of age on social cognition.17 They compared older and younger groups on their performance on three social cognition tasks that required participants to “mentalize,” i.e., to infer the mental/emotional states of others. Older adults performed worse on these tasks and also showed a corresponding decrease in BOLD fMRI signal from the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. The authors interpret their findings as indicating that these social cognitive deficits are localizable to specific regions of the default network and decline with age. Discussing social cognition from a lifespan development perspective, Moran20 examines the effect of typical aging on ToM. He notes that the overarching research question is whether ToM is a function of other cognitive functions such as processing speed and executive function, and whether ToM deficits are mediated by age-related loss in these functions and fluid intelligence, rather than crystallized intelligence. He discusses the possibility that theory of mind may represent “social wisdom” such that a lifetime of accumulated crystallized knowledge makes us more, rather than less, skilled and efficient in our social interactions, a rare example of experience trumping youth. Without extrapolating from ToM to social norms awareness, our finding of age-related decrements in the SNQ22 is consistent with the view that social cognition declines with age.

Longitudinal studies, including further follow-up of this cohort, will allow the determination of whether SNQ22 performance remains stable over time, and whether it predicts subsequent cognitive decline or dementia over time. Meanwhile, it is worth considering that assessment of social cognition might be a useful addition to standard cognitive assessment of older adults. Our data (including the item-by-item distribution across age, gender, and education subgroups, in the supplemental tables) may be useful to other researchers using the SNQ22 on its own or as part of the EXAMINER test battery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding

The work reported here was supported in part by grants # R01AG023651 and #K07AG044395 from the National Institute on Aging.

The authors thank the dedicated staff of the MYHAT project and the many senior citizens who participated in the study.

The authors thank Dr. Kathryn Rankin for sharing the SNQ-22 instrument with our study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Mary Ganguli, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Psychiatry, WPIC, 3811 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-2593, UNITED STATES.

Zhaowen Sun, University of Pittsburgh.

Eric McDade, Washington University in St. Louis.

Beth Snitz, University of Pittsburgh.

Tiffany Hughes, Youngstown State University.

Erin Jacobsen, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Chung-Chou H. Chang, University of Pittsburgh

References

- 1.Henry JD, von Hippel W, Molenberghs P, et al. Clinical assessment of social cognitive function in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(1):28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shany-Ur T, Rankin KP. Personality and social cognition in neurodegenerative disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(6):550–5. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834cd42a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gur RC, Gur RE. Social cognition as an RDoC domain. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2016;171B(1):132–41. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosentino S, Zahodne LB, Brandt J, et al. Social cognition in Alzheimer’s disease: a separate construct contributing to dependence. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):818–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kramer JH, Mungas D, Possin KL, et al. NIH EXAMINER: conceptualization and development of an executive function battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20(1):11–9. doi: 10.1017/S1355617713001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Possin KL, Feigenbaum D, Rankin KP, et al. Dissociable executive functions in behavioral variant frontotemporal and Alzheimer dementias. Neurology. 2013;80(24):2180–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318296e940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rankin KP. NACC FTLD Module Training: Behavioral Assessments. University of California; San Francisco, Department of Neurology: [accessed 6.29.2017]. https://www.alz.washington.edu/NONMEMBER/FTLD/rankin.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganguli M, Snitz B, Vander Bilt J, et al. How much do depressive symptoms affect cognition at the population level? The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(11):1277–84. doi: 10.1002/gps.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mungas D, Marshall SC, Weldon M, et al. Age and education correction of Mini-Mental State Examination for English and Spanish-speaking elderly. Neurology. 1996;46(3):700–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganguli M, Bilt JV, Lee CW, et al. Cognitive test performance predicts change in functional status at the population level: the MYHAT Project. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(5):761–70. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganguli M, Chang CC, Snitz BE, et al. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment by multiple classifications: The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) project. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(8):674–83. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cdee4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkinson GS. Wide Range Achievement Test-Revision 3. Wilmington, DE: Jastak Association; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran JM, Jolly E, Mitchell JP. Social-cognitive deficits in normal aging. J Neurosci. 2012;32(16):5553–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5511-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frith CD, Frith U. Mechanisms of social cognition. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012:63287–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sollberger M, Rankin KP, Miller BL. Social cognition. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2010;16(4 Behavioral Neurology):69–85. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000368261.15544.7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moran JM. Lifespan development: the effects of typical aging on theory of mind. Behav Brain Res. 2013;237:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.