Abstract

Context

There is a scarcity of early palliative care interventions to support family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer living in the rural Southern U.S..

Objective

Adapt the content, format, and delivery of a six session, palliative care, telehealth intervention with monthly follow-up for rural family caregivers to enhance their own self-care and caregiving skills.

Methods

Qualitative formative evaluation consisting of one-on-one, semi-structured interviews with rural-dwelling persons with metastatic cancer (n=18), their primary family caregiver (n=20), and lay patient navigators (n=26) were conducted to elicit feedback on a family caregiver intervention outline based on published evidence-based interventions. Transcribed interviews were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. Co-investigators reviewed and refined preliminary themes.

Results

Participants recommended that intervention topical content be flexible and have an adaptable format based on continuous needs assessment. Sessions should be 20 minutes long at minimum and additional sessions should be offered if requested. Faith and spirituality is essential to address but should not be an overarching intervention theme. Content needs to be communicated in simple language. Intervention delivery via telephone is acceptable but face-to-face contact is desired to establish relationships. Other internet-based technologies (e.g., video-conferencing) could be helpful but many rural-dwellers may not be technology savvy or have internet access. Most lay navigators believed they could lead the intervention with additional training, protocols for professional referral, and supervision by specialty-trained palliative care clinicians.

Conclusions

A potentially scalable palliative care intervention is being adapted for family caregivers of rural-dwelling persons with advanced cancer and will undergo piloting in a small-scale randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: family caregiving, cancer, palliative care, lay navigation, rural, intervention development

Introduction

The taxing role of family caregiving for persons with advanced cancer and other life-limiting illnesses has been recognized as a public health crisis1,2 and is a priority focus in palliative care.3,4 Of the 13 million persons in the United States (US)5 who have advanced cancer, caregivers provide an average of 8 hours of daily assistance6 that can result in burden, strain and poor physical and psychological health, particularly as their care recipients near end of life.7–9 A particularly vulnerable population of family caregivers are those living in the rural Southeastern U.S. who lack access to palliative care. In Alabama, which received a D grade in a 2015 State-by-State Report Card on palliative care access,10 55 of 67 counties are rural.11 This is a significant public health problem in Alabama and other Southeastern states because these rural populations have large proportions of underserved groups,12,13 use palliative care and hospice at lower rates,14–16 and demonstrate marked disparities in advance care planning and end of life care.17–19 Similar palliative care disparities for rural-dwellers have also been reported outside the U.S., such as Canada, Australia, Africa, and Europe.20–23 Caregivers play a vital role in palliative care access and delivery24–27 and hence there is a critical need to support them. However, there are few palliative care interventions or care models specifically developed to be culturally sensitive to these family caregivers.

To address this gap, the purpose of this study was to elicit feedback on and identify modifications to an outline of an early palliative care intervention for rural-dwelling family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer living in the rural South based on published evidence-based interventions.28–30 The primary research question was: What are preferences of rural-dwelling Southern advanced cancer family caregivers regarding the topical content, format, and delivery of an intervention to help support their care of a person with advanced cancer and their own health and well-being? An additional objective was to ascertain what role lay healthcare navigators might assume in the delivery of this intervention. Non-medically trained lay healthcare navigators, a role that has proliferated since its inclusion in the U.S. Affordable Care Act,31 provide one-on-one guidance to patients and families as they move through the healthcare system and whose services can include assisting with insurance and financial issues, explaining treatments, providing emotional support, providing transportation, coordinating care, and communicating with the healthcare team.32,33 This study represents the first phase of developing a scalable, evidence-based intervention that addresses the needs of advanced cancer family caregivers. Once modifications have been incorporated, the intervention will be protocolized and evaluated for feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy at improving patient and caregiver outcomes in a pilot, small-scale randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Methods

This was a qualitative formative evaluation study, 34 reported here following Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines.35 One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with rural-dwelling patients with advanced cancer, their primary family caregivers, and lay healthcare navigators to gain feedback on the outline of a palliative care intervention for advanced cancer family caregivers. The sampling was purposive, including different stakeholders (caregivers, patients, and lay navigators) and different advanced cancer types, in order to elicit a range of perspectives needed to identify modifications to the intervention. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Review Board (Protocol #X150611005 and X140521002).

Sample, Setting, and Recruitment

Advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers

Rural-dwelling, advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers were recruited from the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center. Patients ≥21 years of age were eligible if: 1) they had advanced cancer, defined as Stage III/IV lung, breast, gynecologic, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, brain, melanoma, and hematological cancers and 2) they were rural-dwelling as defined by having a home address zip code that was classified by the U.S. Census’ Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes system as small rural, large rural, and isolated (hereafter referred to as “rural”). Family caregivers ≥21 years of age were eligible if they self-identified or were identified by the patient as a relative, friend, or partner with whom there is a close relationship and who assists with but was not paid to provide medical care. Caregiver participants did not have to live in the same residence as the patient. Patients and caregivers were excluded if they had a medical record-documented (patients only) or self-reported active Axis I psychiatric diagnosis of severe mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), substance use disorder, suicidal ideation or dementia/confusion because the intervention was not being designed to be robust enough to address the additional issues of these populations.

Between October 2016 and October 2017, the UAB electronic medical record was regularly screened to identify patients meeting the eligibility criteria who had a planned outpatient visit at the cancer center in the coming 1–2 weeks. After gaining permission from oncology providers, project managers (CC, TR) met with patients and their family caregivers prior to their visit to inform them about the study. Project managers invited those eligible and willing to participate in individual, 1-hour interviews with the principal investigator (PI) (JNDO) either in-person or over the telephone, and complete informed consent. All participants were remunerated with a $20 check.

Lay healthcare navigators

Between April and July 2015, lay healthcare navigators were recruited who were employed as part of Patient Care Connect, a Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMMS) demonstration project.36 Patient Care Connect lay healthcare navigators from 11 participating community cancer centers in Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, and Florida were eligible to participate who self-endorsed serving patients and families in rural areas. One site declined to participate. The PI met with navigators privately in person to describe the study, invite participation, obtain signed informed consent, and conduct a 1-hour interview.

Interview Guide and Intervention Outline

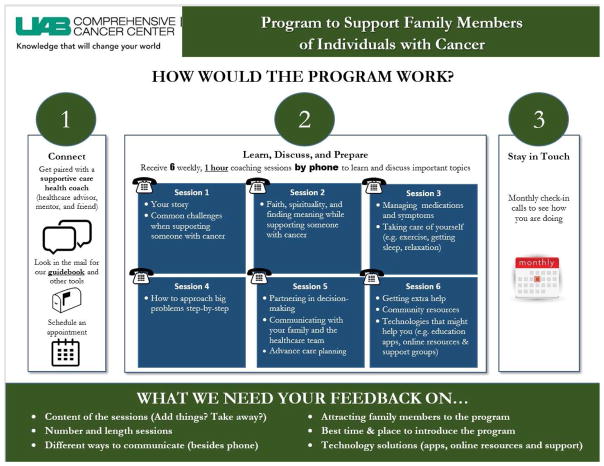

One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted following a guide aimed at answering the research questions (see Table 4 for sample interview questions). During the interview, participants were oriented to a 1-page outline of a telephone-based advanced cancer family caregiver intervention (given to them during clinic recruitment) and asked open-ended questions about the outline (Figure 1). The intervention outline was developed based on the content, format, and delivery of trial-tested cancer family caregiver interventions from the Rosalynn Carter Caregiver Intervention Database, the ENABLE (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends) family caregiver intervention,28 and McMillan’s COPE Caregiver intervention.37,38 Consistent with the length and number of sessions in other family caregiver interventions,39,40 the tentative intervention was proposed to consist of 6 structured, weekly, 1-hour phone sessions with a telehealth coach (potentially a nurse, social worker, or lay healthcare navigator) that would be introduced within 60 days of their relative being diagnosed with advanced cancer (which reflects published guidelines of early palliative care).41 Coaches would then check-in monthly to address ongoing or new issues. Prior to the interview, participants wereinformed that any aspect of the intervention could be modified and encouraged to offer critical feedback that would help the intervention be feasible and meet the needs of rural-dwelling advanced cancer family caregivers.

Figure 1.

Data analysis

Semi-structured interviews were professionally transcribed, uploaded into Atlas.ti software, and analyzed using a thematic analysis approach.42 The PI (JNDO), a board certified hospice and palliative care advanced practice nurse and experienced qualitative researcher, first independently open-coded the first 5 transcripts for each of patient, family caregiver, and navigator participant groups. Through discussion with members of the study team (RAT, CC, TR, MM, MB), a list of preliminary codes was generated. Using this code list, subsequent line-by-line coding of transcripts was performed by the PI. Through in-depth discussion and review of codes and raw text, the list of codes was organized into theoretically meaningful themes, aided by matrices to facilitate within and across-case analysis by case and code.43 To corroborate findings, foster researcher reflexivity, and establish trustworthiness, study team members met every 1 to 2 weeks throughout the entire data collection and analysis process to provide feedback on the data collection and analysis process and on the emerging codes and themes. After consultations with the study team, consensus was reached that data saturation had been met after 26 navigator interviews, 19 caregiver interviews, and 18 patient interviews. One additional caregiver interview was completed wherein no new insights emerged.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 shows patient (n=18), family caregiver (n=20), and lay healthcare navigator (n=26) participant characteristics. Patients had a mean age of 58 years and were mostly male (66.7%), White (83.3%), married or living with partner (77.8%), Protestant (88.9%), and unemployed (50%). Over half had a high school education or less (60.2%) and half were in poor or fair health (50.0%). Family caregivers had a mean age of 56 years and were mostly female (95%), White (85.0%), married or living with partner (90.0%), and Protestant (85.0%). Most (70%) had a spousal relationship to the patient and had been performing in the caregiving role for a mean of 27 months. Most (55%) cared for patients every day and for more than 8 hours per day. Navigators had a mean age of 44.7 years and were mostly female; nearly 40% of the sample was African-American/Black. Over three-quarters had a college or master’s degree. The mean years of experience in the navigator role was 2 years.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics

| Patients (n=18) | Family Caregivers (n=20) | Lay healthcare navigators (n=26) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Age, Mean (SD), Range | 58.0 (10.4), 40–84 | 56.0 (12.8), 28–77 | 44.7 (13.5), 26–66 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 6 | 33.3 | 19 | 95.0 | 21 | 80.8 |

| Male | 12 | 66.7 | 1 | 5.0 | 5 | 19.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 15 | 83.3 | 17 | 85.0 | 15 | 57.7 |

| African-American/Black | 3 | 16.7 | 3 | 15.0 | 10 | 38.5 |

| Asian | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married or living with partner | 14 | 77.8 | 18 | 90.0 | - | - |

| Divorced or separated | 3 | 16.7 | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

| Single | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Widowed | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| Masters | 1 | 5.6 | 2 | 10.0 | 6 | 23.1 |

| College graduate | 2 | 11.1 | 2 | 10.0 | 14 | 53.9 |

| Some college | 3 | 16.7 | 7 | 35.0 | 5 | 19.2 |

| Vocational | 2 | 10.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| High school | 9 | 50.0 | 7 | 35.0 | 1 | 3.9 |

| Some high school | 2 | 10.2 | 2 | 10.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Socioeconomic Status (Total Household Income) | ||||||

| <$30,000 | 6 | 33.3 | 8 | 40.0 | - | - |

| $30,000-$49,999 | 5 | 27.8 | 3 | 15.0 | - | - |

| >$50,000 | 7 | 38.9 | 8 | 40.0 | - | - |

| Rather not say | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Protestant | 16 | 88.9 | 17 | 85.0 | 18 | 69.2 |

| No religious affiliation | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 3.9 |

| Other | 1 | 5.6 | 2 | 10.0 | 7 | 26.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Employment Status | ||||||

| Employed full time | 5 | 27.8 | 7 | 35.0 | 26 | 100.0 |

| Employed part time | 1 | 5.6 | 4 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Retired or Homemaker | 3 | 16.7 | 7 | 35.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unemployed | 9 | 50.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Advanced cancer type | ||||||

| Genitourinary | 6 | 33.3 | - | - | - | - |

| Lung | 3 | 16.7 | - | - | - | - |

| Hematologic | 3 | 16.7 | - | - | - | - |

| Brain | 2 | 11.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal | 2 | 11.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Breast | 1 | 5.6 | - | - | - | - |

| Gynecologic | 1 | 5.6 | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| My health is… | ||||||

| Poor or Fair | 9 | 50.0 | 6 | 30.0 | - | - |

| Good | 4 | 22.2 | 8 | 40.0 | - | - |

| Very Good or Excellent | 5 | 27.8 | 6 | 30.0 | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Relationship to patient (This person is my…) | ||||||

| Spouse/partner | - | - | 14 | 70.0 | - | - |

| Parent | - | - | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

| Child | - | - | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

| Other family member | - | - | 2 | 10.0 | - | - |

| Sibling | - | - | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

| Friend/Neighbor | - | - | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Months as a caregiver, Mean (SD), Range | - | - | 27.1 (34.9), 1-135 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Days per week providing care | ||||||

| <1 | - | - | 5 | 25.0 | - | - |

| 4–5 | - | - | 3 | 15.0 | - | - |

| 6 | - | - | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

| Everyday | - | - | 11 | 55.0 | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Hours per day providing care | ||||||

| <1 | - | - | 4 | 20.0 | - | - |

| 1–2 | - | - | 5 | 25.0 | - | - |

| 3–4 | - | - | 2 | 10.0 | - | - |

| 5–6 | - | - | 1 | 5.0 | - | - |

| 7–8 | - | - | 2 | 10.0 | - | - |

| >8 | - | - | 6 | 30.0 | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| Navigator experience (years), Mean (SD), Range | - | - | - | - | 2.07 (1.9), 0.7–2.3 | |

Qualitative Findings

Table 3 illustrates the main themes, illustrative quotes, and intervention modifications based on the themes. The main themes are organized into the 3 domains addressed in the interviews: content, format, and delivery.

Table 3.

Qualitative themes, illustrative quotes, and intervention modifications

| Main Themes | Sample Quotes | Intervention Modifications |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Content | ||

| (a) Make topical content flexible so that it matches an individual’s specific needs | “…maybe the coach should…do…a primary assessment, or some type of preliminary assessment. At least get some kind of idea of what they think this person may need, and then tweak it as they go along……” –Caregiver 19 “The most important thing would be to do the first assessment…it will guide you to the next place and then this will be the framework of what is going to be covered…“ –Navigator 25 |

|

| (b) Keep content simple and visual | “…When they call…walk’em through it…“ –Caregiver 23 “…having large print, so possibly some little diagrams that people can look over. …Pictures help more…” -Navigator 03 “I can make sense of a lot of things by seeing it through a video…because it’s showing me, not trying to tell me…some people that don't comprehend very well big words, intelligent words, they need it in more of a layman's terms. Something simple to talk about and in a way that they can understand.” - Patient 09 |

|

| (c) Assessing spirituality/faith is important but should not be an overarching theme. Crises should be referred to a spiritual professional. | “…let it be an option that's put out there for 'em. …assess their level of spirituality and how deeply rooted their family history is, or their particular history is, in religion and maybe go from there.” – Caregiver 19 “I would definitely think that’s somethin’ you’d have to find out about an individual…You don’t wanna make them think it’s all about spirituality.” –Caregiver 33 “It is hugely important I think for it to be there, but I think it needs to be almost like optional.”–Navigator 06 |

|

| Domain 2: Format | ||

| (d) Some participants may desire more than six sessions | “Six sessions sound about right. I can’t tell you, for sure. I may still need more sessions when you get through with that number six one.” -Caregiver 20 “…six sessions sounds about right…especially at first, when everything is so hectic and so—just trying to get everything straightened up and leveled out and everybody in place to take care of them. That’d be great.” -Caregiver 32 |

|

| (e) One hour may be too long for some people | “It’s gonna be different for each person depending on where they is in their journey. Just because I may only need 15 minute or 30 minutes this month don’t mean 6 months from now, I don’t need an hour.” –Caregiver 09 “I think that's a good target is one hour…sometimes it may last less than an hour, sometimes it may last a little more depending on what may be goin' on in their lives at that time…” - Caregiver 19 “I think an hour a time on the phone is kinda hard sometimes to carve that much time out of your day…I think 30 minutes would be really easy for most people.” -Caregiver 23 |

|

| Domain 3: Delivery | ||

| (f) Internet access is a problem in rural areas even though using internet-based technology (e.g., smartphone apps, websites) might be helpful | “Well, it might work if you have a good internet connection… Ours is very, very, very, very slow. …That’s why I don’t even get on e-mail anymore, because if I try to download somethin’ it takes forever and a day. … I just stay away from it, because we got about the slowest e-mail internet thing…” -Caregiver 22 “…in rural areas, they don’t have internet. They can’t get it even if they wanted to.” –Caregiver 24 “A lot of people [in rural areas] don’t [have internet]. It’s very expensive. … When you live like we live way out in the country there’s only certain options for you to have internet. … I find that one of my biggest struggles.” -Caregiver 33 “I think that’s a good people for people that’s computer-savvy, but people that are not, maybe somebody can come and help them. … I think a lotta people that could do it, would do it, and those that don’t would probably wanna learn how.” -Patient 18 |

|

| (g) Using a mostly telehealth approach is acceptable but initial face-to-face contact is desirable to establish the relationship | “I’d want a face to face…that would make me feel …that this is a real program and they really, really care.” –Caregiver 28 “Any opportunity for face to face…enhances your value on multiple, multiple levels…shows our depth of care.” –Navigator 16 |

|

| (h) Mixed views on lay navigator role in intervention | “I like the team approach…it’s a collaborative thing…“–Navigator 03 “…it would need to fall into more of a counselor context…“–Navigator 07 “Do I think a lay navigator could do something like this? Yes…I do, most definitely.” -Navigator 23 “I think if we are given the right trainin’ for this, we could be the coach…“ –Navigator 05 |

|

Intervention Content

Make topical content flexible so that it matches an individual’s specific needs

All participants (patients, family caregivers, and navigators) responded positively towards all of the proposed intervention topics. They expressed that the topics all seemed “relevant” and “appropriate” and that none should be removed. A number of patient, caregiver, and navigator participants suggested that the intervention content be flexible, such that more emphasis and greater depth could be placed on topics that caregivers felt they needed. As one caregiver stated, “Everyone won’t have the same needs, I’m sure, so that if you had a way of determining that that would be probably better” (Caregiver 23). There were also multiple suggestions to systematically assess a caregiver’s situation over time as needs evolve due to patients’ progressive illness. Several navigators expressed that it might be better to move the content on identifying your support network and outside resources to the second session because that would address any urgent logistical needs that caregivers might have.

Keep content simple and visual

In general, all participants struggled with having ideas about how to assist those with limited literacy. For those who did comment, they advised having materials be easy-to-read and visual and having coaches trained to talk through content orally. Some patient, caregiver, and navigator participants suggested using videos, although they cautioned that many might not have a DVD player.

Assessing spirituality/faith is important but should not be an overarching theme. Crises should be referred to a spiritual professional

All participants were very cautious in their advice about how to incorporate faith and spirituality into the intervention. Many commented on how there are people of many different types of faith and it would seem challenging to address. Though nearly all felt that assessing a person’s spiritual health was appropriate, none felt that it should be overarching theme of the intervention. Several navigators suggested having a chaplain or other religious professional available for referral if more intensive spiritual counseling was requested:

“I would definitely get with a chaplain services…if it needed to be escalated where someone from the ministry needed to be placed as a part of this if the caregiver is requesting spiritual help” (Navigator 05)

Navigators also recommended combining spirituality/faith within Session 3 Self-Care.

Intervention Format

Some participants may desire more than six sessions

Nearly all participants felt that 6 weekly intervention sessions seemed appropriate and no participants expressed that 6 sessions would be too many. As some of the quotes in Table 3 from caregivers alluded to, having additional sessions added might be helpful as caregiving needs tend to change over time as patients become sicker. Caregivers were not specific about any content in particular but rather emphasized that the content that is needed at present might be different from what is needed in the future even though they could not predict what that future content might be.

One hour may be too long for some people

Most patient, caregiver, and navigator participants felt that the intervention sessions should have a flexible time allotment, depending on the caregiver’s availability and need. Many felt that an hour would be too long because caregivers had busy schedules, might not like talking on the phone for that long, and simply might not have much to talk about for a particular session’s content. Nearly all participants reported that between 15 and 30 minutes would be the “right” amount time for a session.

Intervention Delivery

Internet access is a problem in rural areas even though using internet-based technology (e.g., smartphone apps, websites) might be helpful

Most patients, caregivers, and navigators felt that internet-based technologies such as video chat or text messaging might be helpful but that internet access in rural areas is limited or expensive. Some caregiver and patient participants did not like internet-based applications (e.g., “we’re not into that”), while numerous others spoke about how many caregivers might not have the skills to figure out how to use internet-based technology without assistance.

Using a mostly telehealth approach is acceptable but initial face-to-face contact is desirable to establish the relationship

In general, all participants felt that interaction with a coach over the telephone was acceptable because it was “convenient” and did not require having to drive to an appointment. However, nearly all participants desired having at least some face-to-face contact, particularly at the beginning of the program during the first session. Many felt that such face-to-face interaction laid the foundation for “trust” and “rapport” and that it would send the implicit message that the family member was validated and appreciated. Some patients, caregivers, and navigators commented on how the face-to-face contact would enhance the communication during sessions, allowing individuals to express themselves more and adhere to the program. Others made comments about how it would help the program to feel “real” and like the coaches “genuinely cared”: “Personally, I like to see the person face-to-face…I’m not really good on telephones. I don’t like that distance between whoever I’m talkin’ to… I prefer the personal touch” (Caregiver 22). When asked where this face-to-face contact could take place, patients, caregivers, and navigators spoke about how this would need to be negotiated with the caregiver but could include their home, a public location close to their homes (e.g., library, fast-food restaurant), or during patient visits at the hospital.

Mixed views on lay navigator role in intervention

All navigators expressed that they already regularly interacted with family caregivers as part of their patient navigator role and some mentioned that they already addressed many of the recommended topics with family caregivers. For example, they were already addressing practical needs like arranging transportation and parking for families and providing some degree of “emotional support” and “spiritual support.” Navigators expressed a range of views about their potential role in delivery of the intervention. Some felt that navigators should have a very limited role because it would greatly increase their workload and because they did not feel comfortable discussing certain topics, such as how to manage symptoms or medications. Other navigators stated that they could work in partnership with the nurse coach by helping link caregivers with resource needs identified by the coach during sessions. Finally, several navigators thought that they could lead this type of intervention. They indicated that they would need more training and access to a “backup” healthcare professional for supervision and questions. Some talked about being comfortable as a first line of support and that if a family member had a particular need, being able to refer that person to another healthcare professional.

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative formative evaluation was to elicit feedback on the outline of an early palliative care, telephone-based intervention for advanced cancer family caregivers living in the rural Southeastern U.S., developed based on published evidence-based interventions. Findings from analysis of interviews with 18 patients, 20 family caregivers, and 26 lay patient navigators will be used to inform the development of the intervention protocol tailored specifically for this underserved population. Results indicated retaining several aspects of the intervention, including the proposed topical content, the inclusion of faith and spirituality, and the use of a mostly telehealth approach.

Other findings pointed towards more substantial modifications. First, participants emphasized having at least some in-person contact with the coach to enhance the genuineness and empathic connection. This connection, or what has been called therapeutic alliance, has been identified as a reliable predictor of positive psychological outcomes regardless of the counseling approach.44,45 Some participants mentioned that such a connection facilitated by face-to-face contact might increase the likelihood of caregivers adhering to the program, an observation reinforced in psychotherapy research.46

Second, participants stressed having topical content that was flexible and responsive to the specific needs of caregivers as these needs changed over time. Adaptive interventions, designed to customize content and dose of an intervention to the heterogeneous needs of different individuals, are being increasingly tested in behavioral interventions,47 however their use in caregiving interventions has been limited,48 representing a novel direction for our to-be-developed intervention protocol as well as future caregiving research in general.

Third, participants expressed that faith and spirituality should not be an overarching theme of the intervention. This was surprising given that Alabama and other Southeastern U.S. states have been reported by a Pew Research Center study as the most religious states in the nation.49 Participants conveyed that their faith and spiritual needs were best met through their local communities of worship; however they did feel that assessing and asking about one’s faith and spirituality should still be an included topic of the intervention.

Finally, the number of participants who expressed reservations about the use of internet-based technologies in the intervention due to the lack of internet access was expected. According to a U.S. Federal Communications Commission report, Alabama has 15 “critical need” rural counties wherein less than half of residents have broadband access, though this access appears to be improving over time.50 Any use of internet-based technology in our intervention will need to be carefully pilot tested for feasibility.

Regarding delivery, there were a wide range of perspectives from the lay patient navigators concerning their possible role the family caregiver intervention. Some expressed having an ancillary role whereby they assisted the coach with specific tasks of the intervention, such as arranging transportation services and identifying caregivers for referral to the intervention. In contrast, other navigator participants felt they could be the coach for this type of intervention so long as they were provided additional training and regular supervision. The use of non-professionally trained healthcare personnel to deliver palliative care in rural areas is increasing but their utilization and scope of practice varies widely.51,52 A recent systematic review51 examining partnerships between volunteers and palliative care professionals in rural areas emphasized the importance of volunteer education and training that emphasizes practice limits and boundaries and where volunteer communication and debriefing with overseeing healthcare professionals was imperative. The palliative and supportive care workforce is not expected to meet the demand in the coming decades relative to the growing need for services;53 hence, developing models of care that leverage lay healthcare navigators may represent a solution to this impending crisis.33,52,54

While our study provides insights about adapting an intervention for rural advanced cancer family caregivers, several limitations should be noted. This study included only the first phase of formative development and did not include proof-of-concept testing. Thus, the modified intervention is still in development and there is a need to determine feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy. However, our stakeholder engagement strategy, incorporation of evidence-based intervention elements from other successful family caregiver interventions, and our rigorous formative evaluation approach has resulted in findings that greatly enhance the rigor of our intervention adaptation process. It is also possible that a larger sample size that included more Blacks/African-Americans and male caregivers could have resulted in a broader set of themes. However, the make-up of the caregiver sample is consistent with the racial demographics of the Southeastern U.S. Furthermore, there may be different perspectives concerning modifications to the intervention based on different background characteristics (e.g., higher hours/week caregiving vs. fewer hours/week). We aim to incorporate adaptive elements to the intervention design that will be potentially beneficial to caregivers regardless of demographic background and will furthermore seek to over-recruit minority and male caregivers in our future, small-scale pilot RCT. Finally, our study focused on a very particular U.S. rural culture, and hence, some of our results may not be transferable to other global rural populations. While recent reviews have highlighted the increasing role and potential of lay workers bringing palliative care to rural communities globally,55,56 we recommend that programs in other countries and rural settings gain stakeholder feedback from their own populations before testing or implementing similar programs.

This formative evaluation study elicited feedback and recommendations from rural-dwelling persons with advanced cancer, their family caregivers, and lay healthcare navigators on modifications needed to adapt a palliative care intervention to support the well-being and skills of an underserved rural Southeastern U.S. family caregiver population. Key modifications including adaptive content, regular needs assessment, mixed in-person and telephone encounters, and flexibility in encounter length will be incorporated into an intervention protocol and tested for feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy in a pilot, small scale RCT. While efficacious cancer family caregiver interventions are growing in number, major issues remain concerning their tailoring to real-world implementation and their inclusion of vulnerable populations, including rural-dwellers and minorities.41,57 Consequently, it is imperative to continue refining, tailoring, and testing the potential impact of palliative care interventions for underserved advanced cancer family caregivers.

Table 1.

Sample interview questions

Intervention Content

|

Intervention Format

|

Intervention Delivery

|

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Palliative Care Research Center (Career Development Award) and by the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) (1K99NR015903). Dr. Rocque is funded by an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Investigative Medicine. Dr. Bakitas is funded by the NIH/NINR (R01NR013665). The authors would like to thank partnering UAB oncologists who assisted with identification and recruitment of patient and family caregiver participants. The authors would also like to thank all patients and their family caregivers and lay patient navigators of the Patient Care Connect program who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Assuring Health Caregivers. Neenah, WI: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudson P, Remedios C, Zordan R, et al. Guidelines for the psychosocial and bereavement support of family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(6):696–702. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4362–4373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Liao KP, et al. Caregiver symptom burden: the risk of caring for an underserved patient with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(5):1070–1079. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P126–137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson PL, Thomas K, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D. Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3):522–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center to Advance Palliative Care. America's Care of Serious Illness: 2015 State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in our Nation's Hospitals. New York, NY: 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alabama Rural Health Association. [Accessed May 14, 2014];Alabama Rural Health Association's Definition of Rural. 2011 http://www.arhaonline.org/about-us/what-is-rural/arha-s-definition-of-rural/

- 12.Alabama Department of Public Health. Alabama Health Disparities Report 2010. Montgomery, AL: Office of Minority Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rural Policy Research Institute. Demographic and Economic Profile: Alabama. Columbia, MO: Rural Policy Research Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329–1334. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak J, Haley WE, Chiriboga DA. Racial differences in hospice use and in-hospital death among Medicare and Medicaid dual-eligible nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):32–41. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bossuyt N, Van den Block L, Cohen J, et al. Is individual educational level related to end-of-life care use? Results from a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Belgium. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(10):1135–1141. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0952-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, Prigerson HG. Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(17):1533–1540. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(33):5559–5564. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.4733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumont S, Jacobs P, Turcotte V, Turcotte S, Johnston G. Palliative care costs in Canada: A descriptive comparison of studies of urban and rural patients near end of life. Palliat Med. 2015;29(10):908–917. doi: 10.1177/0269216315583620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavergne MR, Lethbridge L, Johnston G, Henderson D, D'Intino AF, McIntyre P. Examining palliative care program use and place of death in rural and urban contexts: a Canadian population-based study using linked data. Rural Remote Health. 2015;15(2):3134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jansson M, Dixon K, Hatcher D. The palliative care experiences of adults living in regional and remote areas of Australia: A literature review. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53(1):94–104. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1268063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rainsford S, MacLeod RD, Glasgow NJ, Phillips CB, Wiles RB, Wilson DM. Rural end-of-life care from the experiences and perspectives of patients and family caregivers: A systematic literature review. Palliat Med. 2017;31(10):895–912. doi: 10.1177/0269216316685234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams AL, Bakitas M. Cancer family caregivers: a new direction for interventions. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(7):775–783. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudore RL, Casarett D, Smith D, Richardson DM, Ersek M. Family Involvement at the End-of-Life and Receipt of Quality Care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funk L, Stajduhar K, Toye C, Aoun S, Grande G, Todd C. Part 2: Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published qualitative research (1998–2008) Palliat Med. 2010;24(6):594–607. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stajduhar K, Funk L, Toye C, Grande G, Aoun S, Todd C. Part 1: Home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998–2008) Palliat Med. 2010;24(6):573–593. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. Benefits of Early Versus Delayed Palliative Care to Informal Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: Outcomes From the ENABLE III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMillan S, Small B. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: a clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):313–321. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMillan S, Small B, Weitzner M, et al. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2005;106(1):214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 119 (2010).

- 32.Natale-Pereira A, Enard KR, Nevarez L, Jones LA. The role of patient navigators in eliminating health disparities. Cancer. 2011;117(15 Suppl):3543–3552. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer SM, Sauaia A, Kutner JS. Patient navigation: a culturally competent strategy to address disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(5):1023–1028. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rocque GB, Partridge EE, Pisu M, et al. The Patient Care Connect Program: Transforming Health Care Through Lay Navigation. J Oncol Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.008896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2005;106(1):214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMillan SC, Small BJ. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: a clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(2):313–321. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, Schafenacker A. Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2005;14(6):478–491. doi: 10.1002/pon.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(1):96–112. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attride-Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 2001;1(3):385–405. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miles M, Huberman A, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3. Thousand Oakes: Sage Publications, Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ardito RB, Rabellino D. Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Front Psychol. 2011;2:270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muran J, Barber J, editors. The Therapeutic Alliance: An Evidence-Based Guide to Practice. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharf J, Primavera LH, Diener MJ. Dropout and therapeutic alliance: a meta-analysis of adult individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2010;47(4):637–645. doi: 10.1037/a0021175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nahum-Shani I, Hekler EB, Spruijt-Metz D. Building health behavior models to guide the development of just-in-time adaptive interventions: A pragmatic framework. Health Psychol. 2015;34S:1209–1219. doi: 10.1037/hea0000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zarit SH, Lee JE, Barrineau MJ, Whitlatch CJ, Femia EE. Fidelity and acceptability of an adaptive intervention for caregivers: an exploratory study. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(2):197–206. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.717252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pew Research Center. America's Changing Religious Landscape. Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Federal Communications Commission. Rural 2017: Critical Need Counties in Broadband and Health. Washington, DC: Federal Communications Commission; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Connell B, Warner G, Weeks LE. The Feasibility of Creating Partnerships Between Palliative Care Volunteers and Healthcare Providers to Support Rural Frail Older Adults and Their Families: An Integrative Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34(8):786–794. doi: 10.1177/1049909116660517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, et al. Resource Use and Medicare Costs During Lay Navigation for Geriatric Patients With Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):817–825. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, Wolf SP, Shanafelt TD, Myers ER. Future of the Palliative Care Workforce: Preview to an Impending Crisis. Am J Med. 2017;130(2):113–114. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fischer SM, Cervantes L, Fink RM, Kutner JS. Apoyo con Cariño: a pilot randomized controlled trial of a patient navigator intervention to improve palliative care outcomes for Latinos with serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(4):657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tedder T, Elliott L, Lewis K. Analysis of common barriers to rural patients utilizing hospice and palliative care services: An integrated literature review. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29(6):356–362. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bakitas MA, Elk R, Astin M, et al. Systematic Review of Palliative Care in the Rural Setting. Cancer Control. 2015;22(4):450–464. doi: 10.1177/107327481502200411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]